Abstract

I first outline a theory of audit and evaluation building on Cultural-historical Activity Theory (CHAT) and Power’s critical perspective. Second, I draw on some recent empirical case studies of teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge, in particular teachers’ understanding of their students’ mathematical knowledge. In summary, these studies show that the teachers’ judgments were influenced by their own mathematical knowledge and by their teaching experience; and that their knowledge was strongly task-situated and tool-mediated rather than ‘in the head’. Pedagogical content knowledge is at the boundary between reflection and the practice. Third, this suggests dangers, and opportunities in auditing teacher knowledge. I finally argue that the distribution of audit and evaluation across politically competing activity systems implies tensions between de-coupling and colonisation, which I explain are based on exchange- and use-value contradictions in the underlying knowledge economy.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge

- Mathematical Knowledge

- Teacher Knowledge

- Propositional Knowledge

- Strategic Knowledge

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

In this chapter, I first outline a theory of audit and evaluation building on Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) and Power’s (1999) critical perspective and present an analysis of audit and evaluation in education in general. Second, I draw on some recent empirical case studies – mainly conducted with my doctoral students – of teachers’ knowledge, in particular, teachers’ understanding of their students’ mathematical knowledge. These studies showed that the teachers we studied sometimes mis-judged their students knowledge; that their judgments were influenced by their own mathematical knowledge and by their teaching experience; and that their knowledge of their students was task-situated and tool-mediated rather than ‘in the head’. Shulman’s notion of pedagogical content knowledge is reconceptualised via CHAT as a boundary object between reflection on teaching and the practice of teaching. Third, I argue the need to examine our methodology for tapping teacher knowledge with due recognition of the danger, or opportunity, presented by teacher knowledge auditing. I finally develop some further implications of CHAT perspectives on pedagogy and its audit or evaluation: The distribution of knowledge across activity systems involves contradictions between ‘de-coupling’ and ‘colonisation’, which I attribute to exchange-value and use-value contradictions in the knowledge economy.

I argue that the problem of auditing and evaluating teachers’ knowledge for teaching requires us to answer some basic questions:

-

What is the purpose of the practices of audit and evaluation, in general and of teachers’ knowledge, in particular?

-

What kinds of knowledge do mathematics teachers need in order to teach or to produce evidence for auditors?

-

How can teacher knowledge be audited/assessed: what tools/technologies are available, or needed?

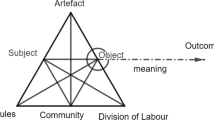

For the analysis of activities and their purposes, I turn to CHAT for theoretical perspectives. The main citations to the original corpus of literature on CHAT are usually to Vygotsky, Luria and Leont’ev, but also sometimes to Bakhtin and Voloshinov, and to the Western developers and disseminators, Cole (1996) and Engestrom (1987, 1991); see also Roth and Lee (2007) for a general review, and Williams and Wake (2007a, 2007b) or Ryan and Williams (2007) in the specific mathematics education context.

It is important to mention that this tradition has influenced another significant socio-cultural current well-known to mathematics educators: that of situated learning in communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Lave, 1996; Wenger, 1998). However, CHAT theory has an extensive history and more extended repertoire of social-psychological, Marxist/ian concepts such as ‘subject’, ‘object’, ‘system’, ‘tool-mediation’ and ‘division of labour’ in ‘activity’ that will prove useful. Thus, auditing and evaluation refer to different social practices, arise in distinct activities, defined by different motives and engage the subjects and subjectivities of those involved in contradictory ways. I ultimately attribute the tensions between audit and evaluation and, what Power calls ‘de-coupling’ and ‘colonising’, to contradictions between the use-value and exchange-value of mathematics in a knowledge economy (see Williams et al., 2009; Williams, in press). I will be drawing on all these concepts here and argue that these perspectives raise new horizons with regard to audit and evaluation of teachers and teacher knowledge.

Accounting for the Dialectic of Audit

Let me begin with the function of audit in society in general, as the recent introduction of audit to teacher knowledge and education has a historical context and Power’s work, inter alia, will prove useful (Power, 1999). The critical sociological literature on ‘audit’ suggests that we face an audit explosion in all public sectors of the economy from health and education to policing. It is widely recognised how dysfunctional this can be and the literature is not without passionate, strongly politically-positioned critiques of its often deleterious, often unintended impact on practice (See several chapters in Strathern, 2000).

In a recent case in the UK, a hospital is discovered to have killed approximately 400 patients as the unintended consequence of its efforts to meet the audit requirements for becoming a ‘Trust’, giving it certain advantages in terms of funding and autonomy over non-Trust hospitals. On the other hand, the consequences of NOT auditing can have unintended consequences too: As I write this chapter, I hear that one consequence of cancelling the national tests for 14-year-olds in England is that many Shakespeare theatre companies have experienced a sudden burst of cancellations by schools (Shakespeare used to be on the test syllabus and so it was worth motivating students even at the cost of a school trip). In both cases the diagnosis is quite simple: management is mediated by proxy measurements for ‘use’ that do not faithfully measure use-value – in the one case the impact on ‘health’ is measured by Accident and Emergency department wait-times, in the other the educational value is measured by the national test scores.

On the other hand, auditing practices are no doubt here to stay and seem to go from strength to strength in the UK: in education, despite powerful critiques and the cancellation of some of the national tests, one may argue it is stronger than ever before. The managerial elites need audit to protect themselves from their own lack of accountability and potential accusations of bad judgment, indeed of having made any personal judgment at all, as ‘personal judgment’ is the only one that can thereby become critical personally (Power, 1999).

With international audits such as TIMSS and PISA, one sees league tables going global: it is not difficult to imagine potentially homogenising effects on education internationally to suit the international labour market and much EU policy seems directed along these lines. Indeed, the nation-states in these circumstances may come to have less room for manoeuvre themselves (Williams, 2005, 2009).

Yet in the education literature, it seems, our theoretical understanding of auditing practices is slim. Power (1999) made an important contribution with the conceptions of ‘de-coupling and colonising’ in this context. I introduce these notions here and their relation to ‘audit’ versus ‘evaluation’ practices:

Audit focuses on verification … Audit is a normative check whereas evaluation … addresses cause and effect issues; audit is orientated to compliance whereas evaluation seeks to explain the relationship between the changes observed and the programme (Power, 1999, p. 118).

Furthermore:

Although forms of self-evaluation are viewed as a necessary component threshold for any spending to be taken seriously, cost effectiveness auditing sits above them …. (p. 118)

Audit is driven by a degree, perhaps a healthy degree, of mistrust and by the need for accountability and some degree of transparency of procedure: thus the audit holds the auditee to ‘account’ to the auditor who, as a result, may influence a flow of resource – essentially it is economic and about the power to control.

(T)he development of auditable performance measures is much more than a technical issue: it concerns the power to define the dominant language of evaluation (within a hierarchy of economy, efficiency, and effectiveness) …. (Power, 1999, p. 117)

Notice here that the hierarchy places economy and efficiency over effectiveness, which implies a colonisation of practice by audit, or the authority of cost-benefits, or of exchange value over the use-value of the outcomes of a practice. Yet evaluation is at heart a self-valuation process, an attempt by practitioner(s) to reflect and to understand and improve what they do: this use is – in the professions, at least – a use-value.

In particular, Power has shown how the tensions involved in audit arise from contradictions between audit from the bottom-up, reflecting evaluations by practitioners and professionals on the ground and audit from the top-down, based on performance objectives set by managers under the regime of ‘New Public Management’. He has used these notions to ground insights into contrasting, empirical case studies, in finance, in health and in Higher Education. My purpose here is to use his approach to re-conceptualise ‘formative’ assessments (broadly corresponding to evaluation) and ‘summative’ assessments (broadly corresponding to audit) and thus reinforce the controversial insight that both are necessary components of a functional assessment process (see Williams and Ryan (2000), which builds on Black and Wiliam (1998)).

Power shows that the entire history of audit involves a problematic: the purpose of audit is said to be to reduce the necessity of relying on the validity of local custom and practice, e.g. of professional subjective judgment. And yet the audit practice is – or claims to be – itself unauditable, i.e. it relies in the end on the professional judgment of experienced auditors and this judgment essentially includes their subjective evaluation (based on finite, even quite small sets of data and impressions) of the people they are auditing. In practice, there is a ‘gap’ between what audit promises and what can realistically be ‘known’ (with limited resources a significant part of the problem).

In addition, the survival of evaluation in a regime of audit creates the need for new measures, i.e. for measures of primary products of practices that professionals believe to be valuable. In some areas of education this can be problematic and I will argue this is the case with teacher knowledge. The problem of measurement technologies has led in some spheres to second-order constructs, whereby the processes of management are measured instead of their products (what we have come to know as Quality Assurance, or what Power refers to as control of control). Thus, it seems auditors can be persuaded to use second order measures as long as they are credible and can be counted. What auditors need is a politically acceptable system that can be credibly said to hold the system being audited to ‘account’ for its outcomes, increasingly against costs on a ‘value for money’ basis.

It emerges from Power’s account that credible auditing in practice always needs to engage with its auditees and their practices. Increasingly, the auditors expect (and on grounds of efficiency this is inevitable) the auditees to actively ‘comply’ with the audit and this provides room for manoeuvre if auditees are to collect data, or maybe even construct their own measures. Indeed, in persuading doctors to collect measures, Power recalls that one of the first moves of audit was to use the evaluation data that doctors already used to monitor practice for formative purposes. Similarly, academics have been brought to engage with research assessment exercises as a means of accounting for their research practices and the associated flow of resource.

Of course there is a huge tension in the purposes of audit and evaluation, as Black and Wiliam (1998) and others have pointed out (an account of this is in Williams and Ryan (2000)). When the ‘bottom-up’ evaluation process breaks free from top-down audit pressures, Power calls this ‘de-coupling’. In the extreme, if decoupled from the practice it is supposed to record, audit may thereby be rendered totally ineffective in holding local practice accountable: typically organisations de-couple by setting up specialist departments to isolate the productive parts of the organisation from its effects. In a number of assessment projects in Manchester, we tried to develop formative and diagnostic work in connection with summative assessment as a means of offering some de-coupling possibilities: by encouraging teachers to focus on the formative aspects of their work with national tests, we sought to counter the most offensive effects of ‘teaching to the test’ – where summative testing effectively colonises teaching practice (see Williams & Ryan, 2000; Williams, Wo, & Lewis, 2007). The use of an ‘audit’ instrument by Ryan and Williams in the service of teachers’ metacognitive evaluation (see Chapter 15 by Ryan and Williams, this volume) is another pertinent example: a device designed principally to measure students’ mathematics knowledge can sometimes be ‘turned’ into a tool for self-evaluation.

When evaluators on the ground find themselves using instruments devised by Ofsted (the national inspection agency for schools in England) to observe each others’ lessons (see e.g. Williams, Corbin, & MacNamara, 2007b; Corbin, MacNamara, & Williams, 2003) then the auditing practice ‘takes over’ the evaluation practice on the ground. Power refers to this as ‘colonisation’ and this neatly describes what happens when teaching becomes dominated by preparation for the tests that were introduced as audit measures. The account of this in Williams et al. (2007a), however, revealed that colonisation can sometimes be contested: teachers can develop surprising resources for turning accountability systems to their own purposes, e.g. turning audit into evaluation. Thus, when teachers – who were also ‘managers’ required to audit their colleagues’ compliance with the so-called three part lesson – saw a ‘great lesson’ that did not conform, they went straight out and told everyone about it.

An important conclusion for understanding of auditing practices is that the tension referred to is actually caused by a ‘contradiction’ between opposite purposes of assessment for audit (usually summative) and evaluation (usually formative). These purposes are part of the contradictory ‘objects’ of two distinct ‘activities’ (‘audit’ and ‘evaluation’) that engage with distinct Activity Systems. The audit system collects data for managers and ultimately the state to count the ‘success’ of their expenditures in practice. Ultimately, the audit justifies a flow of further resource to the primary practice. We say that what is audited is thereby shown to have ‘exchange value’.

On the other hand, the primary professional practice being audited in general self-evaluates as part of its own system in terms of the usefulness of its outcomes, with a view to improving practice in utilitarian terms. In this context, what is evaluated normally is supposed to have ‘use-value’. (For a full exposition of a theory of value in education, see Williams (in press) and Williams et al. (2009).) The trouble arises when the two activities engage together, share common instruments and objects, even subjectivities, as they inevitably do. The hospital manager responsible for the bid for Trust status leans on the Accident and Emergency staff to cut wait-times, patients get insufficient or inappropriate care, patients die. The school bursar no longer has the funds for the trip to the Shakespeare play, because the argument formerly applied by the English staff no longer holds; the funds are distributed elsewhere, the school trip to see Shakespeare is cancelled.

Audit and evaluation in practice always mutually engage and feed off each other: audit MUST engage with local practice to be credible and inevitably WILL try to colonise local practices even to the point of endangering their use. On the other hand, local practice demands to be resourced and professional practitioners will feed the audit system with data accordingly. Indeed, this engagement with audit generally offers opportunities for subversion and the local effects of audit can generally be, to some extent, de-coupled and made useful in evaluation precisely because of auditors’ need for credibility.

Thus, there is always a political struggle over audit and evaluation, their distinct values, systems, objects, sources of credibility and power bases. To understand this is essential to understanding the education system today. For instance, to attempt to ‘deny’ audit may be to try to refuse to engage with powerful social forces and so leave the field open to their colonisation. Rather, we may criticise existing audits, subvert them and devise better technologies that reassert the use of professional evaluation and reflection.

In contrast to the effects of audit on learners in schools, professional auditing of teachers’ knowledge has so far made quite limited inroads into professional practice. In the UK, there has been the introduction of a requirement for teacher educators to audit elementary aspects of teachers’ mathematical knowledge for primary school teaching. Summing up the recent literature, I conclude that we do not know much about the effects of this on trainees or on practice in general.

We know that many of the auditing instruments used are essentially crude tests of mathematics not much different from school mathematics tests, assessing mainly substantive elementary mathematics, though a few attempt to touch on syntactical knowledge (e.g. Rowland, Barber, Heal, & Martyn, 2003). In general, these audits repeat the school assessments that the trainee teachers would have completed some years earlier in school and the same deficit model applied: as Murphy (2003) points out, this can lead to a kind of complacency (‘jumping through hoops’) among those who pass and desperation (or worse, denial) among those who do not. Almost nothing in this work has been done to actually audit ‘teaching knowledge’, i.e. knowledge distributed in the act of teaching.

Let us take an exemplary audit item from this literature: “Some children have measured their desk to be 53 cm by 62 cm. State the possible limits to the lengths of their sides” (Goulding, Rowland, & Barber, 2003).

It is quite evident to me that any teacher in the flow of teaching is going to think: “Well, 53 cm could be anywhere between 50 and 53, as these tape measures tend to stretch, and the desk may have been a true rectangle many years ago, … but why do you ask?” But of course, we are not auditing knowledge in (or even for) teaching, we are auditing schooled knowledge with its arcane conventions, language and values (“State the limits …”), stripped of any practical or pedagogical or even mathematical sense of purpose. In this context, it is surprising that educators reflecting on these audits see them as being broadly positive for teachers in training, i.e. an improvement on what went before. But then, they did write these audits/tests and they do know what went before.

What of the prospect of auditing knowledge for, or distributed in, teaching then? Ball, Thames, and Phelps (2008) report that they have developed some proxies and I will report some potential instruments later in this paper that similarly bear on teacher knowledge of their students’ learning. (In addition, for an account of such assessment of teachers’ knowledge and their own learning, see Chapter 15 by Ryan and Williams, this volume) .

But first, we proceed with the analysis of audit-versus-evaluation by considering: (i) the contradictory purposes of audit and evaluation (exchange versus use); (ii) what kinds of knowledge teachers need to teach (for use) and what they need to display (for exchange); and (iii) what technologies of assessment we need to prevent audit from colonising evaluation.

What Is the Purpose of Audit and Evaluation of Teachers’ Knowledge?

The CHAT analysis of the contradiction referred to above has its roots in two distinct activities and activity systems: those of the auditors (teachers’ managers, certifiers, accreditors and maybe even teacher educators) and those of the auditees (the teachers and student teachers themselves, but maybe also the teachers and their educators, too). Teachers’ knowledge, for the purpose of the activity of teaching, has a different ‘meaning’ and ‘purpose’ from that of teacher knowledge for audit and for their auditors: it can be considered a boundary concept, and when reified in audit practices becomes a boundary object at the interface between the two and so its meaning is contested.

In socio-cultural theory, boundary objects are considered to be interesting theoretically and methodologically: they serve contradictory purposes, being involved in distinct activities, and as such they can provide insights into system dynamics (see e.g. Star & Griesemer, 1989). Thus, by exposing the audit item above to the (incorrect, improper and subversive) point of view of the practising classroom teacher engaged in the (imaginary) flow of teaching, I reveal that it assesses for audit, but not for teaching practice.

Who are the auditors or more significantly the commissioners of audit here, and what does ‘teacher knowledge’ mean for them? I mention a number of groups that may each have distinct interests and between whom there are potentially yet more contradictions and tensions. Politicians, their officers and teacher educators may have need of data to record and monitor the success of their work, and hence to account to their own public audiences – and hence ensuring their own flow of resource.

For these groups, some measure of ‘their’ teachers’ knowledge may provide essential exchange value in meeting their social need for accountability. But in addition, in order for these measures to be credible, there is a need for auditors and their own audiences to believe that the measure does represent something real, some use-value in teaching: this can only be determined by an articulation of a relation to the practice of teaching. Thus, the measure of ‘percentage of teachers who are graduates in mathematics’, say, is only a viable audit measure if there is a credible relation between this measure and teaching or potential teaching quality. This all offers much disputable terrain, but the contest over credibility is not only, or even essentially, an academic one. It is in everyday political discourses and discourses of common sense that the battle is fought by operators on the political stage.

Who are the auditees here and what is knowledge for them? It may be the teachers, for whom their knowledge is both use-value (knowledge needed for them to be able ‘to teach’) and exchange value (the means for them to stake a claim to professional status, possibly accreditation). This signals another contradiction in the commodification of knowledge. The student teachers may unhelpfully become engaged subjectively in this audit process: they may ‘pass’ and therefore their knowledge is credibly ‘assured’, and perhaps then they may have less motivation to learn more. Or, they may ‘fail’ and believe that they are failures, and as tried and well-practised failures they may proceed to learn instrumentally to try to pass and even teach this expertise and knowledge to others.

In conclusion: the essential primary tensions and contradictions of audit and evaluation reside in the contradictions ‘within’ the objects of the activities of teaching and auditing, between the exchange and use-value of the knowledge being audited for the different, contradictory social groups with their different interests. Resolving these contradictions involves auditing and giving exchange value to ‘useful’ knowledge: the introduction of syntactical knowledge to audit is a good start, albeit that this has proved somewhat problematic to teacher education so far.

What Kinds of Knowledge ‘Should’ (Mathematics) Teachers ‘Have’ for – or ‘Display’ in – Teaching?

This is the favourite territory of dispute for the mathematics teacher educator and many a researcher: ‘we’ all like to say that we want more than for teachers to ‘just’ have/display mathematical knowledge, facts and skills they can ‘pass on’ to children/students, while for the public, common sense suggests that this is just what teachers should know and do. This disjuncture between the teacher-educator discourse and that of the general public (to whom government accounts) is ultimately what gives audit so much room for colonisation in the practice of teacher education.

We must also ask, what do teachers need ‘before’ and ‘when’ they teach? Note that in this question the acquisition metaphor (to ‘have’ knowledge) is implicit and the process of ‘display’ appears somewhat strange or at least non-normative (Sfard, 1998). Note also the ‘before’ and ‘when’ that signify distinct audit/evaluation purposes again at the boundary between training and teaching institutions. This is another boundary that signals a contradiction between the exchange value in the feeder institution (e.g. the teacher-training institution) and the use-value in the receiver system such as the school where the teacher will practise. In general, audit and evaluation at the transition or boundary between institutions becomes problematic (see Williams et al., 2009).

Ultimately, it must be argued that the ‘acquisition’ of certain objects of knowledge (concepts, etc.) in pre-service training practices become mediating tools in the subsequent practice of teaching. But the third generation Western version of CHAT due to Engestrom and Cole asks us to attend to contradictions arising from just this kind of linkage between the two. What is reified in one system tends to need a lot of work to become a useful tool in another. When assessment in training becomes a tool of audit, this strengthens the links between training systems with a third system, i.e. the audit system. It becomes more difficult to structure it to the purpose of ‘use’ in teaching, as each system has its own objectives, its own technologies and discourses. Thus, according to Ball et al. (2008) teacher knowledge ‘in mathematics teaching’ is multi-dimensional: this implies that audit instruments that credibly measure this will yield multiple measures and make auditing very complicated and perhaps even impossible. In such cases audit tends to reduce multiple measures to one, thereby constraining the evaluation of use.

In part, this becomes a matter of technology: can we devise assessment tools that bring the training practices in line with ‘use’, but still satisfy the demands of the audit culture for some measure of knowledge that is credible?

How Can We Audit/Assess Teacher Knowledge: What Tools/Technologies Do We Have?

The need for the development of appropriate technologies is by now apparent: the demands of audit require a credible measure, but credibility and de-coupling demand a sense of authenticity in relation to the primary products of teaching. One very simple technology in the field of formative assessment is an apt case to discuss. It is one of a number of studies conducted in which diagnostic assessment instruments were designed for students, but were adapted to assess their teachers’ knowledge too. In addition to the case described here below, we found in a study of primary and secondary school teachers’ knowledge about probability that the effect of teaching experience is distinct to that of prior subject matter knowledge (with the more experienced teachers better predicting learners’ errors, but the less experienced teachers showing better schooled knowledge of the topic; see Afantiti-Lamprianou and Williams (2003)).

I now describe one example in some detail, following the account given in Hadjidemetriou and Williams (2002, 2003). A diagnostic assessment tool, developed from items from the research literature (Bell & Janvier, 1981; Bell, Brekke, & Swan, 1987a, 1987b; Hart, 1981) was constructed, (a) to elicit pupils’ graphical conceptions and misconceptions, and (b) to function as a questionnaire for assessing (and measuring) teachers’ perception of the difficulty of the items for their learners, based on a test instrument of items already calibrated for 14-year-old students learning about graphs. The test instrument was given to a sample of pupils and their teachers in order to establish a link between these two groups and to compare results. (Pupils’ group interviews and teachers’ semi-structured interviews also helped us to validate responses and to gain an insight into the thinking of learners and teachers.)

The items of the diagnostic instrument were deliberately posed in such a way as to ‘surface’ known ‘everyday’ graphical conceptions. It developed from an analysis of the key literature in the field of children’s thinking and involved misconceptions such as ‘slope-height confusion’ (e.g. Bell & Janvier, 1981; Clement, 1985), the tendency towards linear, smooth and other ‘prototypical’ graphs (Leinhardt, Zaslavsky, & Stein, 1990), the ‘graph as picture’ misconception, pupils’ tendency towards reversing the x- and y- co-ordinates, misreading the scale and so on (Williams & Ryan, 2000). One example is given in Fig. 10.1: the four interesting responses included linear and inverse correlation and lines that either crossed (32.7%) or failed to cross (5.6%) the x- and y-axes.

Showing the main responses (line-graphs), frequencies (%) and mean ability parameters (measured in Logits1) to an item from Hadjidemetriou and Williams (2002)

TheFootnote 1 pupils’ test was scaled using a Rasch methodology resulting in a five-level hierarchy of responses, each level of which was described as a characteristic performance including errors which diagnose significant misconceptions (Hadjidemetriou & Williams, 2002). The key point about Rasch methodology is that it helps develop a unidimensional interval scale for an underlying ‘attainment’ construct (which, in this case, we take to be ‘graphical understanding’: note that in the psychometric literature, the term ‘ability’ is always used as the technical term for this dimension, but for obvious reasons we try to avoid this). Because the Rasch model observes the principle of conjoint additivity, it is the most parsimonious one-dimensional model that meets the essential audit requirement, i.e. that scores can be legitimately added, subtracted or averaged.

However, group interviews also gave us the opportunity to validate the test responses, in particular, that the interpretation of the errors found in the test are symptomatic of the misconceptions discussed in the literature. In general, we found such interpretations to be valid, with just one problematic case of a misconception concerning children’s slope-height confusion (Hadjidemetriou & Williams, 2002).

Twelve experienced teachers also participated in the study. They were asked to answer all the items and: (a) to predict how difficult their children would find the items (on a five-point scale starting from Very Difficult, Difficult, Moderate, Easy, Very Easy); (b) to suggest likely errors and misconceptions the children would make; and (c) to suggest methods/ideas they would use to help pupils overcome these difficulties. Teachers’ knowledge was further explored through semi-structured interviews. From the teachers’ rating scale data using Rasch models, we scaled the teachers’ perception of difficulty and contrasted it with the learners’ difficulty hierarchy (see Fig. 10.2). It was shown that some teachers over- or under-estimated the difficulties of some items. In Fig. 10.3, the circled items are the items that the teachers ‘most mis-estimated’ in terms of their difficulty. Data from questionnaires and interviews suggested that these mis-estimations were due either to: (a) the teachers having the misconception the item was designed to elicit (i.e. a failure of content knowledge), or (b) the teachers incorrectly assuming that pupils required formal understanding of mathematical concepts to answer questions correctly, i.e. a failure of pedagogical content knowledge.

Teachers’ perception and actual pupil difficulty: from Hadjidemetriou and Williams (2002)

The emergence of knowledge about misconceptions: from Hadjidemetriou and Williams (2002)

The teachers’ interviews, on the other hand, confirmed that the majority of them follow similar instructional sequences and that these are aligned with the prescribed National Curriculum. They also revealed that teachers’ judgement of what is difficult is structured by this curriculum sequence: i.e. they sometimes incorrectly think that topics being more ‘advanced’ in the curriculum implies they are more difficult.

Finally, we were struck by these teachers’ apparent lack of awareness, in general, of their children’s conceptions and misconceptions (see Table 10.1). When asked what misconceptions they might anticipate in their planning of teaching, few had much to say; yet when asked to predict errors in response to the test instrument, they were better able to predict what their pupils would do. Thus, these teachers’ (who might generally be described as ‘leading teachers’ in the sense that they were all experienced, promoted to leading positions, or active in education in their region) audited knowledge was highly sensitive to the methodology adopted to collect it (Hadjidemetriou & Williams, 2002). We concluded that their knowledge is ‘distributed’ and that well-researched tools might make all the difference in what they are able to articulate, or to show in practice (see also Chapter 3 by Hodgen, this volume). This suggests consequences for their planning of teaching perhaps, but also for the results of audit.

Shulman (1986) proposes that pedagogical content knowledge appears in three different forms: propositional knowledge (e.g. knowledge of students’ errors and misconceptions drawn from the literature), case knowledge (e.g. a personal, vivid classroom experience of an error that a teacher was surprised by) and strategic knowledge (i.e. the art of acting in the moment, in particular, to act in situations of information overload, openness, or lack of knowledge relevant to the situation). Much knowledge is presented by teacher educators in the form of declarative statements or propositions, possibly framed around a theory, in a logical form. But these often lack richness of context and are, therefore, hard for practitioners to recall or use in practice. According to Shulman, these limitations make propositional knowledge hard to apply. Case knowledge, on the other hand, may bring these propositions to life and embed them in context:

Case knowledge is knowledge of the specific, well-documented and richly described events. Whereas cases themselves are reports of events, the knowledge they represent is what makes them cases. The cases may be examples of specific instances of practice- detailed descriptions of how an instructional event occurred- complete with particulars of contexts, thought and feelings. (Shulman, 1986, p. 11)

By providing teachers with the appropriate tools that will ‘surface’ errors and misconceptions, we hoped to enrich this kind of well-organised but well-contextualised and usable knowledge. Thus, such pedagogical tools might help mediate research knowledge, which might thereby be transformed aptly for teaching practice. All that is then needed is the strategic judgment to use the knowledge effectively in practice.

This link between ‘case knowledge’ and ‘propositional knowledge’ is, in our view, generally best conceptualised not just as a cognitive one (i.e. it is not only based on what teachers know and keep in their mind), but one which is socio-culturally structured, i.e. mediated by well-researched tools in practice. Figure 10.3 illustrates the relationship proposed.

This suggests that teachers acquire (maybe largely through classroom practice) knowledge about their pupils’ errors. This knowledge is tacit, based on the tasks and items used in the classroom. This also relates to teachers’ propositional knowledge. However, if these propositions and pupils’ errors and misconceptions are theoretically organised around tasks that aim to diagnose them, then, firstly, deeper cognitive problems such as misconceptions come to the surface, and secondly, teachers are made aware of them. We concluded that a well-designed diagnostic tool that includes items which will elicit errors that reveal theoretically-based errors (i.e. misconceptions), might help to transform teachers’ tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge that could be used in planning.

In terms of CHAT, the propositional knowledge relates most clearly to research and perhaps teacher education practices of ‘reflection’ on teaching; it is mediated by scientific language, and facilitates reflection and planning, and discourses about teaching generally. But case knowledge is mediated much more obviously by the everyday language of the context of teaching in classroom action, or generally in interaction with learners. Strategic knowledge is wholly embedded in the practice of teaching in the flow of the moment.

Thus, in CHAT terms, I argue that Shulman’s three components of pedagogical content knowledge reveal the way such knowledge sits at the boundary between two different practices. On the one hand, we have the reflection, discussion and theorisation of teaching of the kind found in an inquiry group, or perhaps a staff room, or privately when a teacher is engaged in evaluating, planning, problem solving or reviewing strategies. On the other hand, we have the teaching practice itself. I argue that the different perspectives on knowledge revealed by the two practices explain the difference and the relation between the forms of knowledge proposed by Shulman (propositional, case, and strategic knowledge).

Conclusion

In summary, previous studies have shown that (a) the teachers we studied sometimes mis-judged their students’ knowledge, and their judgments are influenced not only by their own mathematical knowledge, but also by their teaching experience and the intended curriculum; and (b) their knowledge of their students can be strongly ‘task-situated’ and ‘tool-mediated’ rather than ‘in the head’. In fact teacher knowledge is distributed.

All this is suggestive of the observation that audit and evaluation are tool-mediated, and that these tools shape cognition in practice. But the triple objects of audit, training and teaching practices are at stake here: the tools we use are at the boundary of all three activity systems and need somehow to satisfy the needs of the three systems if they are to become stable. On the contrary, the contradictory demands of the three practices may create instability, political contestation and tend towards colonisation or de-coupling. The triumvirate involves an interesting set of power relationships.

Audit tools can be critical in shaping the backwash effects of audit and need to be thought through in terms of their affordances for the colonising or decoupling of practices. It seems to be important that the tools we designed potentially coordinated training and teaching practice and also the propositional and case knowledge implicated. It also seems to be important that they can be used to construct summative measures and hence offer tools for audit. In this sense they might provide affordances for three systems and practices.

There will always be this uneasy struggle over the use of assessment tools. If any one community gains the upper hand such as that implied by decoupling or colonisation, it can lead to dysfunctional practices that may serve no-one. Even Prime Minister Tony Blair was discomforted when confronted on live television by a patient who observed that, since his government had introduced an audit measure of waiting times for medical appointments that punished centres where times went over 2 days, doctors’ surgeries had started refusing to make appointments (de-coupling) more than 2 days in advance, leaving the patient angry and frustrated. Why don’t auditors see this coming?

Let us imagine, then, the unintended consequences of audit in advance. If audit tools become a means to control a flow of resource, one should ask how this will distort their use in evaluation. In general, it becomes more important for the subject to get the right answer (a measure has to have right answers) than to learn. We must anticipate that if a measurement becomes high stakes in the assignment of exchange value, then the use of the tool for knowledge creation purposes in the primary practice at stake may be compromised.

In conclusion, I have argued that educational researchers need to understand audit as a practice and the contradictions inherent in it that might be politically exploitable. I have given an example from our own development work of how tools that audit knowledge-for-teaching provoke the realisation that knowledge is socio-culturally distributed. A credible audit of knowledge-for-teaching requires engagement with useful evaluation of learning and the development of case and propositional knowledge that might be productive for teaching in practice. Hence credibility of audit tends to produce a de-coupling effect – perhaps a necessary corrective in these colonised times. On the other hand, the engagement of ‘evaluation and use’ value with ‘audit and exchange’ value imposes some of the constraints of audit on practice, e.g. audit abhors multidimensionality and complexity. This contradiction fuels tendencies towards colonisation.

Discussion: Towards a Collective Subject

I have appealed to social, cultural analyses of audit, evaluation and assessment practices in the foregoing argument, and especially to the way that tension and political conflict arises from contradictory practices and their objects (e.g. use and exchange values). In reflecting on empirical work in assessment, I have focussed on how particular tools may mediate audit and evaluation in significant ways.

It is increasingly obvious and widely recognised, I believe, that practice is mediated by tools and that, therefore, audit is sensitive to the technologies of surveillance available. Less obvious or less well known is our analysis of the social forces at work in audit and the consequences for understanding what is possible, and how and why productive or unproductive coupling, de-coupling or colonisation might be designed. Finally, I suggest some new directions where the CHAT perspective might lead.

First, CHAT recognises tool-mediation in object-orientated activity as only one mediating factor among many that may be the source of significant contradictions and therefore, dynamics. In addition, CHAT recognises the division of labour, governed by social, cultural, historically-formed ‘norms’ that position differently disposed subjects in collective activity. Furthermore, in particular, CHAT recognises the inner contradictions within the subject and within the object of activity, and between activities and their bounding activities through boundary objects and boundary crossers (Cole, 1996). Finally, CHAT recognises the possibility of ‘expansion’, for instance, via the re-formulation of the object of activity, or the formation of the collective subject (Engestrom, 1987, 1991).

Where might these notions lead in the case of the audit of teacher knowledge? First, it is significant that pedagogical knowledge is distributed in assessment tools, but this is only one cultural reification of a more general social distribution of knowledge.

To credibly formulate the problem of auditing pedagogic knowledge at the level of the individual teacher or student-teacher logically requires the presumption of a ‘normative’ level playing field consisting of (a) a scheme of work, the departments’/schools’ plans, etc., (b) a standardised textbook and teaching resources, and (c) a common assessment and professional development system, inter alia. However, each institutional, classroom and pedagogical context is different. Appealing for a normative uniformity of affordances in school context is not only unrealistic, it is equitable to the point of being revolutionary.

If pedagogic knowledge then includes the assembly of knowledge distributed across the learning-teaching environment, then one must evaluate this in its social context. The result may be to question, not why a teacher is unaware of the learners’ needs, say, but why the scheme of work, the departments’ or schools’ plans, the text book and the assessment and professional development system as a whole, are systemically unaware of the learners’ needs. In this view, a teacher’s knowledge can only be evaluated at the level of the system and the remediation of the system is at issue: the blame for weaknesses becomes distributed. But so then is the remedy, which demands a collective organisation of the many agents involved: this raises the possibility of a community of teachers as a collective subject (see Williams et al., 2007b). It may make sense to think increasingly of teacher knowledge in this way as a collective property of a collectively cognising subject: perhaps the department or the school, or even ‘the mathematics teaching profession’ as a whole, though it is necessary to work out the appropriate levels at which evaluation becomes useful.

Then there is the question of the ‘double bind’ (Engestrom, 1987). The central contradiction of schooling, the principal source of alienation of learners, is that between exchange value (the learning of knowledge for accreditation, i.e. for advantage in the future distribution wars over resources, capitals etc.) and use-value (learning useful knowledge that enhances the capacity of the individual/social subject to act usefully). The teacher may experience the same contradiction in relation to their own pedagogic knowledge. The thrust of the argument for the formation of a collective subject rests in finding allies that share an interest in escaping this double bind and in rewriting the rules. What might this mean for teacher knowledge?

The contest over values, surely, will not be decided within the teaching profession alone and is manifest and of interest throughout society. But I suggest that understanding audit and evaluation at least requires us to see how values are critically at issue for our profession as well.

Notes

- 1.

1The average ability [see comment above] of those on the test that made these responses is measured in logits: one logit corresponds approximately to one standard deviation of a normal distribution. Thus, those that drew straight lines with negative slopes would be about one standard deviation above the average of those that drew a positive slope if the sample were normal.

References

Afantiti-Lamprianou, T., & Williams, J. (2003). A scale for assessing probabilistic thinking and the representativeness tendency. Research in Mathematics Education, 5, 173–196.

Ball, D., Thames, M. H., & Phelps, G. (2008). Content knowledge for teaching: What makes it special? Journal of Teacher Education, 59(5), 389–407.

Bell, A., Brekke, G., & Swan, M. (1987a). Diagnostic teaching: 4 Graphical interpretation. Mathematics Teaching, 119, 56–59.

Bell, A., Brekke, G., & Swan, M. (1987b). Diagnostic teaching: 5 Graphical interpretation, teaching styles and their effects. Mathematics Teaching, 120, 50–57.

Bell, A., & Janvier, C. (1981). The interpretation of graphs representing situations. For the Learning of Mathematics, 2(1), 34–42.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7–74.

Clement, J. (1985). Misconceptions in graphing. Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, 1, 369–375.

Cole, M. (1996). Cultural psychology: A once and future discipline. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Corbin, B., McNamara, O., & Williams, J. S. (2003). Numeracy coordinators: Brokering change within and between communities. British Journal of Educational Studies, 51(4), 344–368.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

Engeström, Y. (1991). Non scolae sed vitae discimus: Toward overcoming the encapsulation of school learning. Learning and Instruction, 1, 243–259.

Goulding, M., Rowland, T., & Barber, P. (2003). An investigation into the mathematical knowledge of primary teacher trainees. Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics, 23(3), 73–78.

Hadjidemetriou, C., & Williams, J. S. (2002). Children’s graphical conceptions. Research in Mathematics Education, 4, 69–87.

Hadjidemetriou, C., & Williams, J. S. (2003). Using Rasch models to reveal contours of teacher’s knowledge. Journal of Applied Measurement, 5(3), 243–257.

Hart, K. M. (Ed.). (1981). Children’s understanding of mathematics 11–16. London: John Murray.

Lave, J. (1996). Teaching, as learning, in practice. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 3(3), 149–164.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Leinhardt, G., Zaslavsky, O., & Stein, M. S. (1990). Functions, graphs and graphing: Tasks, learning, and teaching. Review of Educational Research, 1, 1–64.

Murphy, C. (2003). ‘Filling gaps’ or ‘jumping hoops’: Trainee primary teachers’ views of a subject knowledge audit in mathematics. Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics, 23(3), 85–90.

Power, M. (1999). The audit explosion: Rituals of verification. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roth, W.-M., & Lee, Y. J. (2007). ‘Vygotsky’s neglected legacy’: Cultural–historical activity theory. Review of Educational Research, 77, 186–232.

Rowland, T., Barber, P., Heal, C., & Martyn, S. (2003). Prospective primary teachers’ mathematics knowledge: Substance and consequence. Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics, 23(3), 91–96.

Ryan, J., & Williams, J. (2007). Children’s mathematics 4–15: Learning from errors and misconceptions. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Sfard, A. (1998). On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Educational Researcher, 27(2), 4–13.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

Star, S. L., & Griesemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. Social Studies of Science, 19, 387–420.

Strathern, M. (Ed.). (2000). Audit cultures: Anthropological studies in accountability, ethics and the academy. London: Routledge.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, J. (2005). The foundation and spectacle of [the leaning tower of] PISA. In H. L. Chick & J. L. Vincent (Eds.), Proceedings of the 29th conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (Vol. 1, pp. 87–90). Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

Williams, J. (2009). The learner, the learning process and pedagogy in social context. In H. Daniel, H. Lauder, & J. Porter (Eds.), Educational theories, cultures and learning (pp. 81–91). London: Routledge.

Williams, J. (in press). Towards a political economy of value in education. Mind, Culture, and Activity. Draft available from http://www.lta.education.manchester.ac.uk/TLRP/AERA2009%20-%20Julian%20Williams.pdf

Williams, J., Black, L., & Davis, P. (2007a). Introduction to ‘Sociocultural and Cultural–Historical Activity Theory perspectives on subjectivities and learning in schools and other educational contexts’. International Journal for Educational Research, 46, 1–2.

Williams, J., Black, L., Davis, P., Hernandez-Martinez, P., Hutcheson, G., Pampaka, M., et al. (2009). Keeping open the door to mathematically demanding programmes in further and higher education: A cultural model of values. In M. David, et al. (Eds.), Improving learning by widening participation in higher education (pp. 109–123). London: Routledge.

Williams, J. S., Corbin, B., & MacNamara, O. (2007b) Finding inquiry in discourses of audit and reform in primary schools. In J. S. Williams, P. S. Davis, &L. Black(Eds.) Sociocultural and Cultural–Historical Activity Theory perspectives on subjectivities and learning in schools and other educational contexts. International Journal of Educational Research, 46(1–2), 57–67.

Williams, J., & Ryan, J. (2000). National testing and the improvement of classroom teaching: Can they coexist? British Educational Research Journal, 26(1), 49–73.

Williams, J. S., & Wake, G. D. (2007a). Black boxes in workplace mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 64(3), 317–343.

Williams, J. S., & Wake, G. D. (2007b). Metaphors and models in translation between college and workplace mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 64(3), 345–371.

Williams, J. S., Wo, L., & Lewis, S. (2007c). Mathematics progression 5–14: Plateau, curriculum/age and test year effects. Research in Mathematics Education, 9, 127–142.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Williams, J. (2011). Audit and Evaluation of Pedagogy: Towards a Cultural-Historical Perspective. In: Rowland, T., Ruthven, K. (eds) Mathematical Knowledge in Teaching. Mathematics Education Library, vol 50. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9766-8_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9766-8_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-90-481-9765-1

Online ISBN: 978-90-481-9766-8

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)