Abstract

Beyond the appearance the dominant conception of strategic planning is still rooted in the rational comprehensive paradigm of planning. We have added sophistication, i.e., the consideration of the plurality of actors as a constitutive character of the process, the need to construct consensus among different subjects, the selectivity and the attention towards implementation. But the idea is still that of defining objectives and trying to design a set of actions which allow to pursue them.

The chapter presents a different approach in the experiment conducted in Milan. We did not have a strong power to support the plan. Somehow we have been forced to adopt a much less linear approach, characterised by an indirect connection between a structure of argumentation which indicates a direction and a possible evolution of the current situation and a set of actions at different levels. This approach can define strategic planning as a field of practices rather than as a coherent sequence of coordinated actions. The main question is the following: is this way of conceptualising strategic planning just the result of a series of specific circumstances, or is this a promising approach which could be more effective in coping with situations where power is fragmented and strong leadership non-existent - an approach fostering innovation and change?

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Beyond the appearance the dominant conception of strategic planning is still rooted in the rational comprehensive paradigm of planning. We have added sophistication, that is the consideration of the plurality of actors as a constitutive character of the process, the need to construct consensus among different subjects, the selectivity and the attention towards implementation. But the idea is still that of defining objectives and trying to design a set of actions which allow to pursue them.

We have been induced to choose a different approach in the experiment conducted in Milan. We did not have a strong power to support the plan. The Provincial Institution is quite weak, and within weak institutions the power of the politician in charge is not particularly relevant. The territory is not well defined: we have been aware since the beginning that the territory of the Province is just an administrative section of the Milan urban region which, by any definition, is larger than the province. Somehow we have been forced to adopt a much less linear approach. This approach is characterised by an indirect connection between a structure of argumentation which indicates a direction and a possible evolution of the current situation and a set of actions at different levels which are tentative, experimental and which try to push a very fragmented governance environment in the desired direction using various means.

This approach can define strategic planning as a field of practices rather than as a coherent sequence of coordinated actions.

My question is the following: is this way of conceptualising strategic planning just the result of a series of specific circumstances, or is this a promising approach which could be more effective in coping with situations where power is fragmented and strong leadership non-existent – an approach fostering innovation and change?

In order to respond to this question I have to first describe the context and the planning process and then link this to what I consider relevant literature.

2 The Context

The starting point of this process was the request submitted by the Province of Milan to our Department of Architecture and Planning1 at Polytechnic of Milan to develop a strategic plan.

In Italy, we have a three-tier system of local government based on Regions, Provinces and Municipalities. In the specific case in question there is the Region of Lombardia, with about 9 million people, and a Province of Milan, with about 4 million people distributed across 189 Municipalities. Among these is the Municipality of Milan, which accounts about 1.2 million inhabitants. All three levels have statutory land use or spatial planning powers, although the strongest powers remain with those of the municipalities, which are responsible for land use plans, and those of the regions, which are responsible for planning legislation. The Provinces, which are in charge of the Territorial Coordination of Provincial Plans, are a rather weak link in the chain of land use planning.

The Provincial Government elected in June 2004 put forward the idea of developing a strategic plan as an important point in its electoral programme. Accordingly, a special political head, ‘Assessore al Piano Strategico’ (sort of chancellor), was nominated by the President of Milan Province to take responsibility for the strategic plan.

The Provincial Government comprises of 15 Assessori, each with different functions and heading different departments with Territorial Planning, Mobility, Economic Development and Environmental Protection being the most relevant from our perspective. The establishment of specific and separate responsibility for the strategic plan is a sign of political commitment and will. The strategic plan was intended to be different from the statutory territorial plan.

It is important to reflect on the reasons for this choice. Strategic planning in Italy does not have formal recognition (Fedeli & Gastaldi, 2004). No planning law at the national or regional level defines or includes strategic plans among the planning tools. Nonetheless, in the last 10 years in particular a fair number of Italian cities have promoted strategic plans. Turin was the first, starting during the mid-1990s with a process which formed the basis for rethinking the potential of a former ‘one-company town’ that had been hit by the crisis in the automobile industry (Ave, 2005). This was very much inspired by the experience of Barcelona, which was one of the first and most successful in Europe. Then followed Florence, Rome and many other medium-sized cities which are now linked into a ‘network of strategic cities’. Furthermore, in the North of Milan’s urban region some Municipalities had got together at the beginning of the present century to develop a joint strategic plan as a means of coping with problems like infrastructure and transport and economic development and also as a response to the image of external Municipalities in the periphery of Milan.

These experiences spread the idea of strategic planning as an administrative innovation. The first reason for the decision by the Province of Milan was thus that strategic planning was considered as an innovative, proactive form of planning within the realm of political communication. It is planning designed for action and development, different than the idea of ‘planning as control’, linked to statutory territorial planning. And for the new centre-left coalition which had won a very uncertain electoral victory and wanted its activities to be seen as a fresh start for progressive policies, making a strategic plan was part of the picture.

I would add here that all this took place with no precise idea of what kind of strategic plan they wanted to promote. There were various interpretations and expectations within the Provincial Government: the Assessore for Economic Development had in mind a plan centred upon infrastructure and new development poles; the Assessore for Territorial Planning was looking for the strategic vision which was lacking in the Territorial Plan inherited from the previous government. The others had less clear ideas and thought of an instrument to coordinate different sectoral policies. The ambiguity of the idea was not necessarily a problem, in so far as the design of the process could cope with different intentions and interpretations.

Clearly, a symbolic dimension is assigned to the decision to initiate a process of strategic planning and, as Edelman considers, the symbolic value of a decision or a policy is deeply connected with its ambivalence (Edelman, 1985).

A second reason can be recognised in the fact that provinces, as stated earlier, have weak governments. Provinces situated between strong Regions and strong Municipalities, particularly in a situation like that of Milan with a big city at its core, have to fight for their political space. This does not result simply from the sum of formal powers, which are fragmented and articulated in many fields of competences. The institution of the Province is a very old one. Historically it precedes the Region, and is responsible for the provincial road system, for providing infrastructure for higher education, for the production of a provincial territorial plan, for leisure and culture and for some other residual functions. It is quite clear that its powers are many and dispersed, and also that in any specific field of public action they are not so crucial because there are other prevailing powers situated above or below the provincial level.

The government elected in 2004 had chosen to present its political programme under the slogan ‘Province of Municipalities’ (rather than a higher government body above the Municipalities). The slogan was intended to underline the intention of looking for the source of power not in the limited areas in which the Province could impose its decisions over other actors, but in an institution which is at the service of Municipalities and helps them to deal with the many problems that go beyond their individual capacity. The President then elected had many years of experience as mayor of one of the biggest Municipalities in the urban region, and many of the Assessori had experience of having served as mayors. In the context of the relationship with other actors and with the Municipalities, a particularly weighty problem was that of the relationship with the Municipality of Milan. Historically, though particularly in the last 15 years, one of the main obstacles to the Provincial Government’s ability to act within its mandate had been the conflict with Milan. Not being able to cooperate with or to obtain cooperation from the Municipality of Milan, the Provincial Government has been the government of a territory with a ‘big hole’ in the middle. Since most of the problems have their cause or effect in the core city, this difficult relationship turned out to be a major weakness of the provincial power.

The strategic plan was therefore seen as a tool to engender new relationships with other levels of government, with Municipalities and particularly with Milan. It was seen as an experiment in governance, which could strengthen the Provincial Government in its capacity to cooperate, rather than impose decisions in residual areas.

We can conclude here that in this specific situation the decision to prepare a strategic plan was linked to many concurrent reasons, that is the ambiguity of its content, the image of innovation attached to its symbolic value, the interactive character of the process of its preparation and its open nature.

These contextual factors gave us a big responsibility to design a planning process that could be appropriate in the specific situation because, as Albrechts (2004) suggests strategic spatial planning is not a single concept, procedure or tool; it is a set of concepts, procedures and tools that must be tailored carefully to the specific situation. And this is what we have attempted to do.

Another important contextual factor in devising effective policies for the urban region of Milan was the Provincial border. What territory did we have to consider in order to handle things adequately? In recent years, many voices have raised the issue of the growing inter-dependency of an ever-wider territory in the central part of the Lombardy region (Balducci, 2004; Lanzani, 1991; Secchi, 2003). This area has been described as the ‘Infinite City’ (Bonomi & Abruzzese, 2004), a post-metropolitan region which creates space for the building of new territorial relationships. Comparing current images of this area with those of 30 years ago, it is all evident that a deep process of restructuring has taken place.

Firstly, the urban region of Milan, physically, now extends far beyond not just the Municipality but also the Province of Milan, and if we want to get a glimpse of the territorial complexity we probably have to consider as a minimum a region that includes ten provinces belonging to three different regions. Secondly, this expanding urban region is composed of conurbations which appear to have their own territorial form, not just as a result of a sprawl effect of Milan.

This territorial feature is confirmed by population trends: the ten provinces that are totally or partially included in the urban region have an overall population of almost 8 million people. The territory underwent moderate but continuous growth in the years 1981–2001. During that period of time the loss of population from the core city and the Province of Milan (–3.4%) was offset by significant growth in the surrounding provinces of the North – Como (+5.1%), Lecco (+8.7%), Varese (+3.1%), Bergamo (+11.3%) – and the nearer South, Lodi (+10.4%).

A simple observation of territorial phenomena in recent years shows (a) growth of many external areas pushed by the strength of Milan and also by a significant autonomous attraction capacity; (b) the relocation from the city of Milan of populations which belong to different social groups; (c) the localisation of new metropolitan functions in the field of commerce, production and leisure in this enlarged urban region. The above factors gave rise to a new and integrated geography of development.

Furthermore, it can be said that this area altogether also has strong relations with other more distant poles like Turin and Genoa in the west and Brescia and Verona in the east, with which it forms, what Peter Hall has called, a ‘Mega-City Region’ (Hall & Pain, 2006).

According to Hall and Pain a Mega-City Region is formed by “series of anything between 10 and 50 cities and towns, physically separate but functionally networked, clustered around one or more larger central cities, and drawing enormous economic strength from a new functional division of labour. These places exist both as separate entities, in which most residents work locally and most workers are local residents, and as parts of a wider functional urban region connected by flows of people and information carried along motorways, high-speed rail lines and telecommunications cables” (Hall & Pain, 2006; p. 3).

These tendencies have certain implications and they pointed us in two different directions. First, with the objective of designing a strategic plan for the Province, we had to be aware that the Province is just the core part of a large urban region which in turn is part of a Mega-City Region. This should be reflected in the design of the planning process. Second, within its boundaries we cannot consider the Province of Milan as a coherent territory which can be interpreted only along a linear relationship between the core city and its periphery; the Province itself is a polycentric region in which new territorial aggregations expand beyond institutional borders of Municipalities which are physically and socially visible.

In the last 10 years, there have been instances of coordination among Municipalities in this area, with the aim of coping with inter-communal problems and promoting new, more significant territorial identities. These processes are yet to be sustained by some form of institutional recognition. The strategic plan could be part of this process of recognition, bringing these bottom-up experiences into the realm of governance practices (Healey, 2004, 2007).

3 The Planning Process

Given that the Province is not a city, but rather the core of the Milan urban region, right from the start, we discarded the consolidated and successful model used for Barcelona, Lyon and Turin, where the strategic plan was based on the idea of the city as a unitary actor.

The Milan urban region does not have a single institution with the authority to take decisions over an area where there is a thick web of overlapping jurisdictions. Nor did we consider it useful to invest energy in trying to establish an authority for the city region as had been done many times in the past attempts to plan the metropolitan area (Balducci, 2003). This, in the light of what I have illustrated so far, would in any case be partial and insufficient. Wherever the boundary is traced, it would be crossed by territorial phenomena now or in the near future, given the strong integration already occurring at the level of the Mega-City Region. From this perspective the only viable alternative to the establishment of a jurisdiction is to foster cooperation among the existing actors in position of power with their powers, trying to influence choices rather than impose choices from above. It is what has been described as the evolution of urban leadership from ‘power over’ to ‘power to’ influence (Hambleton, 2007) in complex governance contexts.

If we shift our viewpoint in this direction we can see, on the one hand, that the flexibility of the boundaries is not a problem and should be turned from a possible weakness into a strength; and, on the other hand, that while for a statutory territorial plan it is almost impossible to conceive of this kind of flexibility, the open nature of the strategic plan is particularly appropriate to serve a more enabling, proactive and experimental process (Hillier, 2007). Of course this adds complexity to the already complex situation and makes it necessary to conceive of the strategic planning process as a ‘field of practices’ rather than as a set of rules or a precise sequence of actions.

We therefore designed a planning process in which the Provincial Government was to act as the promoter of a cooperative effort intended to prevent the tendencies towards fragmentation of the population and of its territory as well as offer support to the valorisation of its assets.

From the very beginning, we decided to call it a ‘strategic project’ rather than a ‘strategic plan’ in order to emphasise the difference between this and other strategic planning processes. This was a controversial choice, very much discussed in our group. The strategic project is promoted by the Province but belongs to various actors; it consists of many different actions that could eventually give rise to a strategic plan in a dynamic form, that is as a progress report rather than as a final document. The term ‘project’ gives the initiative the more modest but, at the same time, proactive character that we wanted to ensure.

Secondly, we immediately began working on the production of a new vision for the area. We wanted to bring in all the research work we had been doing on the urban region a new synthetic description of the area capable of: (1) making all the actors aware of the ongoing profound transformation processes; (2) offering new representations capturing the main trends, the internal articulation of the area and the development trajectories; and (3) being a constitutive communicative action in a situation in which all the traditional descriptions appeared to be outdated.

The commission given to the OECD (2006) by the Assessore for Economic Development to conduct a territorial review of metropolitan development helped us because it made clear the division of labour between their focus on the fundamentals of regional economy and the associated governance problems and our focus on the more general challenges imposed by the spatial change of the urban region. We saw the two strategic activities as complementary, as they effectively have been.

Our starting point was a highly challenging assumption: the welfare of the urban region can be achieved. The well-being of its inhabitants but also, indirectly, the competitiveness of its economy, is linked in Milan not to the expansion of infrastructure or to big projects, but rather to its capacity to achieve greater liveability by recovering compromised environment and overcoming difficulties that emerge in the daily life of individuals and businesses, consequent results of the strong economic development of the past. This is today the biggest limitation to further development. Therefore the strategic project must aim at promoting a city region that is more comfortable, is more friendly towards its inhabitants and businesses and is capable of rediscovering its environmental quality and preventing social exclusion.

We called this multi-dimensional notion of liveability habitability. We wanted to introduce a term which is not in common use and which might therefore raise public awareness of the general objective of the planning process.

We wanted to underline the fact that for the first time in the history of Milan’s urban development, the problem of habitability is affecting citizens and businesses at the same time. We know in fact that new production does not have to take place in functionally and technically separate places, and above all that the development of the economy needs a city which, on the one hand, is attractive to high-quality workers and, on the other hand, is a place for accumulating creative capital, a complex system of interactions between companies, risk capital services, media, informal economies, private and public institutions, artists’ communities, associations, social networks, the diffusion of know-how and cultures (Dematteis, 2006). The city, the urban region, is the habitable territory which is capable of hosting these rich interactions.

We defined the habitability theme in six different ways:

-

1.

residing – finding a stable or temporary home, improving the common spaces and the connections with the public space and welcoming new populations;

-

2.

moving and breathing – moving by different means, in different directions, finding comfortable waiting spaces for public transport and reducing congestion and pollution;

-

3.

space sharing – connecting people in new public spaces of different types, widening ability to find silence to slow down the frantic pace of life, creating excitement in other places, allowing space for unplanned activities and bringing back nature where it has disappeared;

-

4.

making and using culture – promoting culture in various places, stimulating institutions to engage in dialogue with informal producers of arts and creative culture and sustaining their networks;

-

5.

promoting new local welfare – supporting voluntary actions and solidarity actions, boosting citizen participation and promoting social services for people facing difficulties;

-

6.

sustaining innovation – attracting new talents, developing a policy for human capital and creating a new responsibility for business vis-à-vis the local community in which they operate.

This multi-dimensional definition of liveability attempts to describe the field of activities that we propose as the components of the strategy. To identify these practices it is necessary to look at the processes of de-territorialisation and re-territorialisation which affect the heart of the urban region: on the one hand, we can see the emergence of ‘distance communities’ (Amin & Thrift, 2001), communities of activities, populations relating to each other through new network connections without being rooted in a specific territory: students, immigrants, commuters, groups of young people with common interests in music, sport and so on; all those groups who challenge the traditional relationship between community and place. On the other hand, we can see new territorial rooting processes which link inhabitants not only (or no longer) to Municipal boundaries but also to significantly wider areas, such as North Milan, Brianza, Alto Milandes and Adda Martesana – areas, strongly integrated by mobility development, where we have seen cooperation develop between Municipalities. Strengthening these relationships is the objective of proposing the image of the ‘City of Cities’ as an essential part of a description orientated towards the project.

It is an interpretive image which allows us to say that these conurbations which are found on the maps are not just concentrations of urban development, but can become rich histories of cooperation between communities, enabling them to face problems which go beyond their individual capacity, from environmental protection to land use, or the management of complementary services.

In this sense they are ‘cities’. ‘Milan City of Cities’ is an image that can help public, private and third-sector parties to work towards creating better habitability.

Starting with this set of argumentations, we conceived different streams of action. The entire process was intended to be quite compact in terms of time and was marked by a series of products (strategic document, project atlas and the final version of the plan) and events (conferences, forums, exhibitions and workshops), which it was hoped would bring the plan out of the laboratory and into the city region.

The project was broken down into a series of steps that together were designed to activate a strategic planning process. The first step was a strategic document introducing City of Cities, the strategic project for the Milan urban region (Provincia di Milano & Politecnico di Milano-DiAP, 2006) presented as part of a public initiative in February 2006: a sort of White Paper on the themes of change in the urban region, rich in data and information. It launched the theme of habitability and presented the vision and the strategy. The second step was to initiate a call for projects and good practices (Provincia di Milano & Politecnico di Milano-DiAP, 2007a) which could contribute to the improvement of habitability in the Milan urban region. The idea of the competition was borrowed from a well-known European experience, that of IBA Emscher Park, which used, as a planning strategy, the innovative means of a project competition, through which a series of plans were selected and then guided to realisation. In our case, similarly, we received a huge response from Milanese society: foundations, universities, associations, individual or joint communes, non-profit organisations and private citizens all participated. At the end of a two-stage process of selection we had 259 proposals for good practices and project ideas, which covered all the facets of habitability indicated above and which portrayed a local community that was not only rich and lively but was also keen to enter into a relationship with institutions in order to contribute to the development of relevant public programmes.

The third step was the preparation of an atlas of policies and projects for habitability in the Province of Milan (Provincia di Milano & Politecnico di Milano-DiAP, 2007b), the result of a dialogue with the other 14 Assessori, delegated advisors and their managers. This was, on the one hand, an exercise in self-reflection and reciprocal internal information within the Provincial structure and across the sectors and, on the other hand, an exercise in external communication and information about what the Province was already doing in the field of habitability. There were already 52 projects and policies which could build another network of projects and policies. These in turn could interact with the network of projects and practices coming out of the competition.

The fourth step was the launch of a limited number of pilot projects which were designed to intervene in particularly relevant areas such as the realisation of a peri-urban woodland and the trying out of innovative policies for housing access, or a project for upgrading production spaces (Provincia di Milano & Politecnico di Milano-DiAP, 2007c).

The fifth step was an exhibition organised at the Triennale di Milano, a nationally and internationally recognised institution for the promotion of planning, architecture and design. The exhibition was held in the period May–July 2007 and provided information about the changes in the Milan urban region to a wider audience (10,000 people visited the exhibition) and translated the objectives of the project into a communicative language. It was jointly supported by the Province, the Municipality of Milan and the Chamber of Commerce. The lay-out had at its core the ‘City of Cities Theatre’, a meeting place where for 2 months an uninterrupted series of initiatives were held to construct, both literally and metaphorically, an arena in which people and decision-makers could meet and discuss the future of the urban region.

The final step of this first phase was the presentation in June 2007 of a final document presenting scenarios, visions and ideas for the habitable Milan urban region (Provincia di Milano & Politecnico di Milano-DiAP, 2007d), in which all the streams of action initiated in the planning process were presented at the conclusion of this first phase to illustrate what had been achieved at the different levels and what the project’s aims were for the future.

4 Interpreting Strategic Planning

The conceptualisation of strategic planning has been quite influential since mid-1980s. Strategic planning tried to respond to the need of finding new non-hierarchical modes of planning (Bryson & Roering, 1987; Bryson, 1988), to deal with an uncertain future and to the need to provide an approach capable of ‘planning under pressure’ (Friend & Hickling, 1987).

This need to move from a traditional planning approach (based on a top-down and single-actor-centred activity of comprehensive planning, an un-contested use of technical knowledge and a linear concept of time and space) found promising materials to deal with the uncertainty and complexity of the contemporary world, in the tradition of private sector strategic planning, which is based on a predefined sequence of operations – (a) initial agreement, (b) stakeholders dialogue, (c) swot analysis, (d) definition of the vision, (e) strategy formulation and (f) listing of actions (Bryson & Roering, 1987).

As a matter of fact, European and American literature shows that a strategic approach could imply and allow different perspectives on planning. One which does not refer to the dimension of strategy just in terms of instrumental rationality in order to reduce and treat complex situations, but rather as one able to explore the possible advantages of dealing with (anticipating, but most of all playing with) the multiple and interacting actors’ behaviours (and agencies).

In fact what seems to be at stake, and what leads a possible and necessary ‘inquiry on’ planning through the eyes of a strategic approach, is the wider crisis of the general framing of public action underlying planning processes. Some of the keywords of planning are in fact losing their consolidated meaning and are challenged by the changing landscape of contemporary society (Albrechts, 2001).

Several authors have tried to describe strategic planning as a field of practices able to elaborate new answers to emerging urban problems: the lessons of Lindblom (1975) in the 1970s are now not so far from those of scholars like Healey (2007), Albrechts (2004), Kunzmann (2004), Hillier (2007) or Dente (2007). These researchers offer relevant contributions to planners interested in bringing together an approach to the strategic dimension different from the conventional perspective.

4.1 Strategic Planning as Using the Intelligence of the Society

Charles Lindblom, in an insufficiently well-known essay about planning in which he compares conventional planning with what he calls ‘strategic planning’, holds that this “is a method that treats the competence to plan as a scarce resource that must be carefully allocated, not overcommitted. (…) It is planning that picks its assignments with discrimination, that employs a variety of devices to simplify its intellectual demands, that makes much of interaction and adapts analysis to interaction” (Lindblom, 1975, p. 41). And furthermore: “strategic planning is then systematically adapted in several specific strategic ways to interaction processes that take place of analytical settlements of problems of organisation and change. (… ) Strategic planning plans the participation of the planners (or of the government for which they plan) in interaction processes, rather than replacing the processes. (… ) Strategic planning tries to make systematic use of the intelligence with which individuals and groups in the society pursue their own preferences by moulding their pursuit, rather than substituting the planners’ intelligence wholly for individual’s or groups’. (… ) Strategic planning attempts to develop and plan, in the light of a rationale for deciding which effects are to be achieved through decision and which only as epiphenomena” (Lindblom, 1975, pp. 44–45).

The discussion proposed in very abstract form by Lindblom is full of practical implications. We have to be aware as planners, and to convince our ‘clients’, of the limited possibilities open to us, of the need to be selective, notwithstanding the stronger appeal of the rhetoric of the omnipotence which is pervasive in planning and policy fields. Particularly in complex systems, we have to value interaction as a form of analysis and use planning as a support for social practices rather than as a substitute for them. We have to understand and look for the ‘intelligence of the society’. We have to include in our consideration potential intended and unintended effects.

4.2 Strategic Plan-Making: Connecting Knowledge Resources and Relational Resources

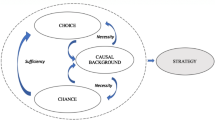

In several critical case accounts and reflections on planning and strategic planning, Patsy Healey proposes to stress the ‘relational nature’ of strategy-making, involving connecting knowledge resources and relational resources (intellectual and social capital) to generate mobilisation force (political capital) (Healey, 1998; Innes & Gruber, 2005). Such resources (capital) form in institutional sites in the governance landscape which, if a strategy develops mobilisation power, become nodes in networks from which a strategic framing discourse diffuses outwards. The strategic frame travels as an orientation, a sensibility and a focus for new debates and struggles, performing different kind of institutional work in the different arenas in which it arrives. At the same time, strategic spatial plan-making is “about building new ideas and about building processes that can carry them forward. (…) A social process, rather than a technical exercise, [which] seeks to interrelate the active work of individuals, within social processes (the level of agency) with the power of system forces-economic organisation, political organisation, social dynamics and natural forces (the level of structure of social relation)” (Healey, 2007, p. 198). It recognises the fact that strategic spatial plan-making, although occurring within a context of powerful structuring forces, may be used by social groups to create structure and frameworks through which to influence the flows of events that affect them (Healey, 1997, pp. 25–26). Below is an assumption about the strategic approach, based on the role of knowledge and relationality within a structured field of action, in a social, political and cultural constructivist perspective.

4.3 Multiple Rationalities: Dealing with Future, Legitimacy and Action

Albrechts and van den Broeck (2004), trying to bridge the gap between theoretical reflection and practical experimentation and to escape from a mechanical view of strategic planning, affirm that effective strategic planning must be able to work at four different levels. The four tracks they propose are as follows:

-

1.

producing a long-term vision;

-

2.

allowing immediate actions;

-

3.

reaching the relevant stakeholders;

-

4.

trying to reach public opinion.

“The four-track approach is based on interrelating four types of rationality: value rationality (the design of alternative futures), communicative rationality (involving a growing number of actors – private and public – in the process), instrumental rationality (looking for best way to solve the problems and achieve the desired future), and strategic rationality (a clear and explicit strategy for dealing with power relationships)” (Albrechts, 2004, p. 752; see also Albrechts et al., 1999; van den Broeck, 1987; 2001).

These four types of rationality are a great challenge to the consolidated rationality of planning, implying new ways to look at the future, to think about efficacy and action and to deal with projectuality and governance. At the same time this is a way of ordering the most relevant aspects of a strategic planning process without fixing them in a set of rigid rules. It is an approach capable of clarifying, in pragmatic terms, what we understand in theory reflecting upon the contribution of Lindblom or Healey.

4.4 Strategic Plans as Open Fields of Experimentation and Investigation: New Maps of Potentialities

Jean Hillier, in her recent book (2007), states that strategic spatial planning should not involve the adoption of pre-determined solutions, but might offer a ‘genuine possibility’ of experimentation for actants to ‘internally generate and direct their own projects’ in direct relevance to their own specific understandings and problematic.

Since 2005, Hillier reflects on a multiplanar theory which explores the potential of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of emergence or becoming as a creative experimentation in spatial planning practices. “These notions allow unexpected elements to come into play and things not to quite work out as expected. They allow (… ) to see planning and planners as experiments enmeshed in a series of modulating networked relationships in circumstances at the same time both rigid and flexible, where outcomes are volatile; where problems are not ‘solved’ once and for all but are rather constantly recast, reformulated in new perspectives” (Hillier, 2005, p. 278).

She therefore proposes that strategic spatial planning be concerned with trajectories rather than specified end-points. She regards spatial planning as an experimental practice working with doubt and uncertainty, engaged with speculation as adaptation and creation rather than as proof-discovery: a speculative exercise, a sort of creative agonistic. She suggests a new definition of spatial planning along the lines of the investigation of ‘virtualities’ unseen in the present; the speculation about what may yet happen; the temporary inquiry into what, at a given time and place, we might yet think or do and how this might influence socially and environmentally just spatial form (Hillier, 2007). She argues for the possibility of planning to be more inclusive, democratic, open and creative, made upon improvisation, based on performance rather than on a normative/prescriptive dimension concerned with ‘journeys rather than destinations’, establishing conditions for the development of alternatives. She proposes a reflection on the activity of mapping practiced in strategic planning as explorations of potentials (in space–time–actors relations).

4.5 Governance Culture and Governance Episodes: New Limited but Practicable Paths of Sense-Making

From a convergent perspective, Healey (2007) again looks at the way in which strategic (spatial) planning is able to help specific episodes of social or institutional innovation to be absorbed into more stable governance practices and can eventually ‘travel’ into different contexts to re-shape the dominant governance culture.

Working through what Lindblom (1990) defines as actions of probing rather than ‘planning’ in a traditional way, one can find a new way to penetrate governance processes and sediment into governance culture. Making governance episodes part of a wider sense-making process, apparently weaker of the great narrations of the past, Healey (2007) offers an insight into what Lindblom calls a strategic planning approach and explains how it is possible (when dealing with complex governance problems) to introduce relevant changes and thus work on innovation starting from alterations at the margin as well as from routines.

4.6 Rethinking Efficacy: Governance as an Open and Complex Key Issue, Rather than a Pre-fixed Model

With Dente (2007), among many other arguments which could be raised and discussed (i.e., the relevance in a strategic approach of dealing with the issue of time intersecting long-term and short-term), we can agree that also the issue of evaluation of planning (assessing outcomes, also unexpected ones) is to be completely reframed in a strategic planning perspective.

The efficacy of strategic planning in fact has to deal with dimensions difficult to be verified and quantified, as the changes in actors’ behaviours, trust, attitude to cooperation, density of network and complexity of projects and issue afforded. In this sense, since, quoting Perulli (2007), strategic planning has to deal with the capacity of identifying issues, rather than objectives to be pursued; has to produce discontinuity, rather than fostering routinary evolution; has to make out possible courses of action, rather than a generic desirable future. Hence its efficacy cannot be simply evaluated through a predefined monitoring model, inside a traditional programming convention. We have to instead develop a sort of continuous process of discussion of the core hypothesis of the plan and their operative declination; this is particularly true, states Dente, if strategic planning is able to renounce to the idea of the public actor as the main and unique actor of the plan.

According to Dente, governance is at stake and is the filtering concept for the evaluation of the efficacy of a plan. This is true when one of the issues of the plan is the difficult reconstruction of a collective actor (a strong dense coalition); it is also true when the plan has already given up with this possibility and can only count on and look for inclusive but open and hetero-direct processes of vertical and horizontal cooperation. To what extent the plan has been able to produce governance changes becomes the issue to be evaluated. But in the first the plan runs after a predefined aspiration (an ideal model); in the second the process remains open to uncertainty, and evaluation is central to feed a recursive process of probing.

This has a further consequence: in the first case it is assumed that a clear coalition, based on an assumption of reciprocal responsibilities, can play a steering collective role, more or less simple to be evaluated. In the second, which abandons from the very beginning the possibility to isolate the subjects from the situations in which they act, the steering role should be played by an actor autonomous from all the other ones involved, able to evaluate the situation and its transformation.

4.7 Potentialities and Transformation, Rather than Action and Outcomes

These positions are not far from those we can find in a recent book by the French philosopher and sinologue François Jullien (2004), which offers an interesting contribution defining the specificity of a strategic approach. His position is based on a 2-fold operation of distance-setting: distance from the modern conceptualisation of planned actions in relation to the eastern world and distance between the western classical thought and the modern one. Jullien, in fact, considers that there is a wide distance between the western-classic approach to the concept of strategy and the oriental (Chinese) one (more similar to the pre-classical Greek culture); looking at the first through the eyes of the second, he suggests, can help deconstructing the western approach and identify both its strengths and weaknesses.

According to Jullien, in the western classical and then modern perspective, ‘efficacy’ passes through a necessary process of modelling, of producing plans to deal with pre-fixed objectives. The plan precedes its application, its implementation, and has to deal with, on the one hand, the intellectual dimension of the production of the ideal form of action and, on the other hand, with the will, which defines the engagement of the individual in getting inside the reality and making the plan work. The distance between theory and practice characterises the ancient Greek classic approach which has been influencing western contemporary thought: a distance occupied and produced by occurring circumstances which deviate from theory and plans, from practice and reality, generating the same friction that one can feel walking inside water rather than on the simple ground (see Strachan & Herberg-Rothe, 2007, about the master strategist Carl von Clausewitz). Leaving behind the pre-classic metis, in Jullien words (the Greek word indicating the capacity to take advantage of circumstances, of seeing the situation evolving, in order to catch the favourable evolution), the classic Greek thought stands far away from the Chinese approach. This indeed, with Sun Tzu and Sun Bin, underlined the importance for the strategist to start from the situation, not one that could be modelled, but from the specific and unpredictable one inside which one happens to be thrown, trying to discover its potential and how to make use of it. In this sense the ‘potential of the situation’ rather than the plan (and the will of the strategist) is relevant, and circumstances cannot be regarded as just producing frictions. Thus rather than about objectives one should talk about advantages that can be taken from a situation. In spite of dealing with the ‘ends-means’ couple, the Chinese perspective uses a word similar to the French agencement. Since strategy can be viewed as the capacity to find all the favourable elements which can be developed in a situation in order to take advantage of it, there is no use of reasoning and acting in the light of finalities. No outcome can be expected, since the situation rather than the subject determination is central. This means also that action has to be thought in another way.

Jullien (2004) suggests using the word ‘transformation’ (within a process perspective), rather than action (related to a product perspective). Where occasion is central, the causal implication of the ‘effect’/outcome is rejected far from the process in which it is strictly embedded. Therefore, efficacy must be indirect in relation to the attended aim. At the same time, whereas subjectivity is fading, strategy becomes indirect and modest, anti-heroic. It is not so difficult to see where Lindblom and Jullien overlap in their approaches and how the approaches to planning proposed by Albrechts, Healey and Hillier try to cope with the challenges proposed by the first one.

5 Reflecting Upon the Provisional Results of ‘City of Cities’ Project

It is too early to try to evaluate the results and outcome of this complex process. If we want to want an answer to the direct question of what changes we have been able to introduce through the strategic planning process, we will be able to indicate only initial, provisional and probably fragile results. I would like to be guided in this reflection by the four tracks proposed by Albrechts (Albrechts et al., 1999). The documents and communications used to develop and present the vision were received by the actors – from the mayors to the representatives of organised interests – with great interest, both in the content and in the perspective offered by a new orientation in a situation of rapid change.

At the same time, we have to admit that the strategy of habitability, which sought to instil a set of new ideas into governance practice failed to change the existing paradigms of the governance culture. The media in general are not attracted to planning actions and documents. The Province as a whole has not endorsed the strategy and the President continues to be more attracted by the hard mainstream ‘infrastructure-and-big-projects’ approach than by the soft objective of designing and implementing a multi-dimensional policy for improving habitability. This is of course linked to our ability to construct a convincing argument, capable of persuading the current leadership (Majone, 1989), but it is also due in no small part to the complex political game of symbolic politics (Edelman, 1985) in which we can play only a minor role.

So far the strategic project has been perceived as a brilliant initiative of very active Assessore (whose function has been re-named ‘Assessore for habitability and the strategic plan’), supported by the Polytechnic. I think the ability of the strategy to conquer the centre-stage has fallen below our expectations. This is linked to the extreme complexity of the process described by Patsy Healey, which takes place on an overcrowded and extremely fragmented arena and where simplified conventional messages always seem to have the edge in political communication.

If we look at our capacity to initiate immediate actions – the second track – we see a story of partial successes and of encouraging hopes. As I said earlier, the competition for projects and good practices achieved a great response, opening up new opportunities for this planning process. In Lindblom’s terms, I see this as a promising way of using the ‘intelligence of the society’; of substituting interaction for analysis; of devising a new enabling role for planning. As a consequence this approach must imply a profound change in the relationship between the public administration and the subjects; a change which emerged as a result of the competition. The problem we had is that the great energy that developed as a result of the competition was only very partially utilised. The lack of preparedness of the bureaucracy of the Province and the fear of being overwhelmed by requests for assistance and funding prevented the Province from committing the public institution to a more open interaction. Those with political and administrative responsibility decided to concentrate only on the ten winners of the competition, in our view failing to understand the nature of the demand coming from the 259 competitors who should have been recognised as discussion partners in a relevant policy process, and should have been supported in creating networks across different projects and practices and helped in creating new communication channels with the public administration.

At the same time it must be noted that many projects were developed independently from the Provincial action and that the method of the competition of projects has seen a diffusion in the planning practices of the Province.

We cannot yet say what may come of this stream of action. We have certainly seen some good developments assisted by the Province and spontaneous organisation of networking, as well as some disillusions. Even so, I do believe that this is a very promising route for planning in general. It is an opportunity to renew the field of participatory planning, engaging the community in a more proactive form of participation. This approach has conquered its legitimacy and in the last January the Assessore has launched a second competition of the ‘City of Cities’ project.

Other immediate actions are the six pilot projects proposed by the Province, which are being developed and the first implementation steps look encouraging.

All this is also indirectly connected to the third track, that of stakeholder involvement. Throughout the process we tried to establish a positive interaction with the various Assessori, officers of different provincial sectors, representatives of interest groups as well as other relevant actors. As stated above, some provisional results have been achieved: the cooperative effort for the preparation of the Atlas of the different sectoral policies, the collaboration in the development of the pilot projects, the partnership with the Municipality of Milan and with the Chamber of Commerce for the Triennale exhibition and the direct involvement of many stakeholders in the competition for projects and good practices. The problem again was how to generate a sufficient level of commitment to produce some kind of intellectual and social capital in the process (Innes et al., 1994); capital that can allow the ideas to ‘travel’ and to sediment into a new culture rather than being a succession of episodes, as Healey (2007) states. It is something which experts and planners can influence only to a limited extent and which depends on the general process of political communication, with a significant role for the media.

Finally, we tried to reach public opinion with information about change in the urban region, problems, opportunities and possible new perspectives. This is cited by Albrechts (2004) as a means of indirectly raising the attention of political actors for the project and also offers a way to root the ideas proposed by the strategic plan in the local community. We tried to do this mainly through the competition and through the Triennale event which, as stated, attracted quite a wide public considering that it was an exhibition about a planning topic. We invested relevant resources in trying to make our messages as clear as possible. This need for communication that could reach the citizens of the urban region was also important for our actions because it pushed us to translate complex concepts into non-technical language, establishing a dialogue with experts in the field of communication with whom we tried to achieve a good level of reciprocal understanding.

By looking back at this intense experience we cannot develop simple conclusions. The process was experimental, full of hopes, difficulties, disillusions and enthusiasm. We are now in the middle of a new phase in which we are working on the second competition for projects aimed at consolidating the results of the first phase, and we are bringing the Triennale exhibition into the territory of the Province in all the cities of the ‘City of Cities’.

If we look back to this 3-years effort, we have to underline that it has been a journey of discovery in the field of uncertainties.

But the final question is: does this experience have to be interpreted as a deviation from a mainstream conception of strategic planning due to the absence of a strong leadership and to the fragmentation of powers, or could it be regarded as an appropriate approach to strategic planning in situations of growing complexity and rapid change of dynamic urban regions?

6 Note

-

1.

The project team: Alessandro Balducci, Matteo Bolocan Goldstein, Paolo Bozutto, Claudio Calvaresi, Ida Castelnuovo, Bruno Dente, Paolo Fareri, Valeria Fedeli, Daniela Gambino, Marianna Giraudi, Arturo Lanzani, Antonio Longo, Fabio Manfredini, Anna Moro, Carolina Pacchi, Gabriele Pasqui, Paolo Pileri, Poala Pucci. Many materials from the Strategic Project City of Cities are available on the website http://www.cittadicitta.it.

References

Albrechts, L. (2001). From traditional land use planning to strategic spatial planning: The case of Flanders. In L. Albrechts, J. Alden, & A. da Rosa Pires (Eds.), The changing institutional landscape of planning (pp. 83–108). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Albrechts, L. (2004). Strategic (spatial) planning re-examined. Environment and Planning B, 31(5), 743–754.

Albrechts, L., & van den Broeck, J. (2004). From discourses to acts: The case of the ROM-project in Ghent, Belgium. Town Planning Review, 75(2), 127–150.

Albrechts, L., van den Broeck, J., Verachtert, K., Leroy, P., & van Tatenhove, J. (1999). Geïntegreerd Gebiedsgericht Beleid: een Methodiek. Research report by KU-Leuven and KUNijmegen en AMINAL, Ministry of the Flemish Community.

Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (2001). Cities. Reinventing the urban. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ave, G. (2005). Play it Again Turin. Analisi del Piano Strategico di Torino come Strumento di Pianificazione della Rigenerazione Urbana. In F. Martinelli (Ed.), La Pianificazione Strategica in Italia e in Europa. Metodologie ed Esiti a Confronto (pp. 35–67). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Balducci, A. (2003). Policies, plans and projects. Governing the city-region of Milan. DISP, 152(1), pp. 59–70.

Balducci, A. (2004). Milano dopo la Metropoli. Ipotesi per la Costruzione di un’Agenda Pubblica. Territorio, 29–30, 9–16.

Bonomi, A., & Abruzzese, A. (eds). (2004). La Città Infinita. Milano: Mondadori.

Bryson, J. M. (1988). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organisations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bryson, J. M., & Roering, W. D. (1987). Applying private-sector strategic planning in the public sector. Journal of the American Planning Association, 53(1), 9–22.

Dematteis, G. (2006). La Città Creativa: un Sistema Territoriale Irragionevole. In G. Amato, G. Varaldo, & M. Lazzeroni (Eds.), La Città nell’Era della Conoscenza e dell’Innovazione (pp. 107–119). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Dente, B. (2007). Valutare il Piano Strategico o Valutare il Governo Urbano? In T. Pugliese (Ed.), Monitoraggio e Valutazione dei Piani Strategici. Pianificazione Strategica. Istruzioni per l’Uso. Quaderno 1, pp. 5–10.

Edelman, M. (1985). The symbolic uses of politics. Urbana, IL and Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Fedeli, V., & Gastaldi, F. (Eds.). (2004). Pratiche Strategiche di Pianificazione: Riflessioni a Partire da Nuovi Spazi Urbani in Costruzione. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Friend, J., & Hickling, A. (1987). Planning under pressure the strategic choice approach. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Hall, P., & Pain, K. (2006). The polycentric metropolis. Learning from mega-city regions in Europe. London: Earthscan.

Hambleton, R. (2007). New leadership for democratic urban space. In R. Hambleton & J. S. Gross (Eds.), Governing cities in a global Era (pp. 163–177). New York: Palgrave.

Healey. (1997). An institutional approach to spatial planning. In P. Healey, A. Khakee, A. Motte, & B. Needham (Eds.), Making strategic spatial plans. Innovation in Europe (pp. 21–29). London: UCL Press.

Healey, P. (1998). Building institutional capacity through collaborative approaches to urban planning. Environment and Planning A, 30(9), 1531–1546.

Healey, P. (2004). Creativity and urban governance. Policy Studies, 25(2), 87–102.

Healey, P. (2007). Urban complexity and spatial strategies: Towards a relational planning for our times. London: Routledge.

Hillier, J. (2005). Straddling the post-structuralist abyss: Between transcendence and immanence? Planning Theory, 4(3), 271–299.

Hillier, J. (2007). Stretching beyond the horizon. A multiplanar theory of spatial planning and governance. Ashgate: Aldershot.

Innes, J., & Gruber, J. (2005). Planning styles in conflict. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 177–188.

Innes, J., Gruber, J., Neuman, M., & Thompson, R. (1994). Coordinating growth and environmental management through consensus building. Policy Research Program Report, University of California, Berkeley, CA.

Jullien, F. (2004). A treatise of efficacy: Between western and Chinese thinking. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Kunzmann, R. K. (2004). An agenda for creative governance in city regions. DISP, 158(3), 5–10.

Lanzani, A. (1991). Il Territorio al Plurale. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Lindblom, C. E. (1975). The sociology of planning: Thought and social interaction. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Economic planning east and west (pp. 23–60). Cambridge: Ballinger.

Lindblom, C. E. (1990). Inquiry and change: The troubled attempt to understand and shape society. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Majone, G. (1989). Evidence, argument and persuasion in the policy process. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2006). OECD territorial reviews: Milan, Italy. OECD Policy Briefs, Paris, pp. 1–7.

Perulli, P. (2007). Una Griglia Metodologica per l’Inquadramento dei Piani Strategici. In T. Pugliese (Ed.), Monitoraggio e Valutazione dei Piani Strategici, Pianificazione Strategica. Istruzioni per l’Uso. Quaderno 1, pp. 27–39.

Provincia di Milano, Politecnico di Milano-DiAP. (2006). Città di Città. Un Progetto Strategico per la Regione Urbana Milanese. Progetto Strategico Città di Città, Milano. Retrieved 04/02/2009, from http://www.cittadicitta.it

Provincia di Milano, Politecnico di Milano-DiAP. (2007a). 10+32+217 Progetti e Azioni per l’Abitabilità: il Bando di Città di Città. Progetto Strategico Città di Città, Milano. Retrieved 04/02/2009, from http://www.cittadicitta.it

Provincia di Milano, Politecnico di Milano-DiAP. (2007b). 6 Progetti Pilota per l’Abitabilità Promossi dalla Provincia di Milano. Progetto strategico Città di Città, Milano. Retrieved 04/02/2009, from http://www.cittadicitta.it

Provincia di Milano, Politecnico di Milano-DiAP. (2007c). Atlante dei Progetti e delle Azioni per l’Abitabilità della Provincia di Milano. Progetto Strategico Città di Città, Milano. Retrieved 04/02/2009, from http://www.cittadicitta.it

Provincia di Milano, Politecnico di Milano-DiAP. (2007d). Per la Città Abitabile: Scenari, Visioni, Idee. Progetto Strategico Città di Città, Milano Retrieved 04/02/2009, from http://www.cittadicitta.it

Secchi, B. (2003). Urban scenarios and policies. In N. Portas (Ed.), Politicas, Estratégias e Oportunitades (pp. 275–283). Lisboa: Fondaçao Calouste Gulbenkian.

Strachan, H., & Herberg-Rothe, A. (2007). Clausewitz in the twenty-first century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van den Broeck, J. (1987). Structuurplanning in de Praktijk: Werken op Drie Sporen [Structure Planning in Practice: Working on Three Tracks]. Ruimtelijke Planning, 19(II.A.2.c), pp. 53–119.

van den Broeck, J. (2001). Informal arenas and policy agreements changing institutional capacity. Paper of the First World Planning School Congress, Shanghai.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2010 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Balducci, A. (2010). Strategic Planning as a Field of Practices. In: Cerreta, M., Concilio, G., Monno, V. (eds) Making Strategies in Spatial Planning. Urban and Landscape Perspectives, vol 9. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3106-8_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3106-8_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-90-481-3105-1

Online ISBN: 978-90-481-3106-8

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)