Abstract

Sprawl is recognized as one of the distinctive features of the urbanizing landscape in almost all countries irrespective of their urban developmental status; but despite a growing volume of literature on this subject the concept continues to elude us. In the context of the changing urban landscape such as the declining growth rates of the metro cities, the spatial expansion of their peripheral urban land into the surrounding countryside, and the sudden growth of the newly reclassified former villages as ‘census towns’ in the last decade, sprawl studies—primarily in the context of individual city regions—have gained momentum in India in recent years. This paper aims to make a small contribution to the literature by focusing on the Delhi Urban Agglomeration (DUA), one of the dynamic city-regions of the world. Given the universal emphasis on density as one of the major dimensions of sprawl, we used a simple and measurable density index based on census data to compute the density levels of ‘census towns’ around the core city in the DUA during 2001–2011. The results show an incremental change towards scattered low-density settlements across the study area that may portend future sprawl. The study points to the suitability of using simple measurable indices based on easily available and nationally applicable data for detailed multi-dimensional empirical studies on sprawl. Apart from theoretical interest, such studies at national and regional scales across India would be of value to planners from the standpoint of sustainable development in the urban agglomeration regions of mega cities.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In contrast to the fact that Mega cities with populations over ten million population were virtually non-existent in the Asian scene until the mid-twentieth century, currently seven of ten such cities are located in Asia. Their rapid growth over the last decades, along with their associated socioeconomic and spatial changes, including the formation of sprawling and often haphazard, low-density population settlements around the core cities have emerged as some of the significant characteristics of contemporary Asian Urbanization. India houses three such mega-cities, Mumbai (18.4 million), Delhi (16.3 m), and Kolkata (14.1 m). Although it is difficult to draw generalizations from the urbanization traits evident in such a vast continent exhibiting a variety of socioeconomic and political environments and the varied roles assumed by the respective countries in managing urban development (UN-Habitat 2008), the Indian pattern is perhaps illustrative of many of these traits. Over the past decade, the million-plus cities of India grew from 35 to 53, increasing their share of the urban load from 38 to 43 %, while their rates of growth declined over the decade; all three mega-cities in India have experienced this declining growth rate over 2001–2011. The declining growth rates of the very large metropolitan centers, relative to the higher growth rates of other cities adjacent to the regions outside the boundaries of the core cities are reshaping the urban territorial landscape akin to the “doughnut effect” (as described in UN-Habitat 2008). Nationally, a ‘new generation’ of dispersed large centers has begun to challenge the historically dominant, very large monocentric cities that are being transformed into the mega-cities of today (UN-Habitat 2008). The recent growth of the “census towns,” formerly rural settlements now meeting certain census-defined ‘urban’ threshold characteristics and estimated to account for between 26 and 30 % of the urban growth in the 2001–2011 decade (Pradhan 2013)Footnote 1 is an example of the changing face of urbanization in India that has gained much recognition in the current academic literature (e.g., Pradhan 2013; Denis et al. 2012) as well as in the popular press (see, for example, a serious of six articles on census towns published in the Hindustan Times 2012). In this process, along with the continued territorial expansion of urban land and acquisition and designation of previously non-urban places as urban, sprawling low-density settlements spatially extended into the peripheries of the large cities are fast becoming an increasingly noticeable feature of the urban landscape in India. Overall, it has been argued that improvements in economic conditions and infrastructural and other linkages coupled with relative success or failure of the spatial development policies may explain at least some aspects of this evolving phenomenon (Satterthwaite 2007) that are also applicable in India.

Sprawl in its many interpretations (e.g., sprawl, fringe, edge-city, leap-frog settlements etc.) has been almost ubiquitous in the urban scene elsewhere in the developed, and some developing countries, but is just beginning to gain momentum in India. Similarly, extensively researched in the developed world, sprawl as a phenomenon, a feature, or a complex amalgam of features (depending on how it is viewed), is now gaining attention in the developing countries and a sizable body of significant empirical work (primarily relying on GIS and remote sensing technology), have emerged in the context of India in the recent years (e.g., Asif 2014; Asif and Rahman 2013; Rahman et al. 2011; Sudhira et al. 2004; Basawaraja et al. 2011; Jat et al. 2008; Fazal 2001). The purpose of the current study is to add to this emerging literature with a brief report on our effort to utilize Census population data in measuring urban density of census towns around the core city in the Delhi Urban Agglomeration (DUA) during 2001–2011. We will start with a brief discussion of the research context, followed by methodology, research findings and a few concluding thoughts on possible future research implications.

2 Research Context

The definition of sprawl has eluded researchers long before the beginning of this century (e.g., Harvey and Clark 1965) when researchers labelled it as an ‘elusive concept’ (e.g., Galster et al. 2001; Fulton et al. 2001) that meant “different things to different people” (Brueckner 2000, pp. 160–161). A decade later, described and analyzed in a variety of ways depending on the perspectives, interpretations, and disciplinary orientations of the researchers, the concept of sprawl continues to be marked by ambiguity and lacking in clarity, coherence, and consensus (e.g., Arribas-Bel et al. 2011; Bhatta et al. 2010; Kew and Lee 2013; Jaeger et al. 2010). As numerous researchers have acknowledged, one of the reasons for this ambiguity lies in its complexity. Based on their perusal of the literature in the social sciences and planning fields, Galster et al. (2001) grouped the prevailing definitions of sprawl in six general categories, namely, as an example that embodies the characteristics of sprawl (e.g., scattered or low-density patterns of urban development such as Los Angeles), aesthetic judgment, cause[s], consequence[s], patterns (e.g., low density, leapfrogging), and finally, as process, and remarked that the definition was “lost in semantic wilderness”. The literature is replete with studies of sprawl and its associated issues from diverse disciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives (for overviews on the literature, see for example, Ewing 1994, 1997; Burchell et al. 1998; Arribas-Bel et al. 2011: 2–5). But, despite many innovative and significant contributions to define sprawl, the ‘semantic wilderness’ continues to this day. In addition, every observation, concern, and recommendation on the nature, causes and consequence of sprawl continues to be filtered through the positive or negative viewpoints of the observer, which has added to the general feeling of equivocality. However, as Arribas-Bel et al. (2011) put it:

“one can interpret this situation in at least two positive ways: first, it is an unmistakable proof that urban sprawl, whatever we refer to by those two words, is a relevant issue that is present and affects many people’s lives; second, this apparent chaotic situation also represents an opportunity to obtain a much richer understanding of what it really is about.

The problem does not come from the great number of interpretations per se, but because of the lack of agreement about the meaning and structure of the term.” (2011, p. 1) [Emphasis added.]

In their effort to bring such meaning and structure, researchers have offered, and are continuing to offer, a wide range of measures, constructs, indices, and definitional parameters of sprawl and its associated issues (e.g., Altieri et al. 2014; Jaeger and Schwick 2014; Kew and Lee 2013; Ewing 2003; Ewing et al. 2002; Galster et al. 2001) that, although beyond the scope of discussion in this short paper, have made significant contributions to the literature.Footnote 2 Suffice to say that although most have recognized sprawl to be a multi-dimensional phenomenon, density has come up as one of the most commonly used measures of sprawl (e.g., Ewing et al. 2002; Galster et al. 2001; Torrens and Alberti 2000; Frenkel and Ashkenazi 2008).

Among the researchers that Wolman et al. (2005) noted for making a contribution by focusing on density in order to operationalize the definition of sprawl such as Fulton et al. (2001), Lopez and Hynes (2003), Lang (2003), and Nasser and Overberg (2001), (as cited in Wolman et al. 2005), Lopez and Hynes have offered a number of strong arguments in favor of their proposed density index utilizing census data that we would like to discuss more at length as a number of their arguments resonate with the purpose of our study.

Lopez and Hynes (2003) considered density to be “perhaps the most important dimension of sprawl,” but agreed with Galster et al. (2001) that it was more than a matter of density: ‘sprawl also contains the dimension of concentration,’ and claimed that their proposed index was based on both of these dimensions (2003, p. 332).Footnote 3 According to them (2003, pp. 330–331), ‘a good sprawl index should strive’ to be measureable and applicable, objective (based on ‘quantifiable data’ ‘collected without bias’), and independent of scale (‘… not be skewed by the size of an individual metropolitan area’). Then, drawing from Coulter’s (1989) ‘indexes of inequality,’ they added four other criteria, namely, definition, information use, interpretability, and simplicity (Coulter 1989 as cited in Lopez and Hynes 2003). They considered the “technologically reliant methodologies [e.g., GIS]” to be “limited by problems of scale and financial cost,” and decided to utilize the U.S. Census data for their sprawl index. They deemed the census to be ‘one of the best data sources on population’. Their argument in favor of the census rested on its reliability, regularity (every 10 years), and the fact that it is “generally accepted as an authority on a number of demographic and geographic issues including the definition of U.S. metropolitan areas themselves” (2003, p. 332). As mentioned above, we found much in the reasoning offered by Lopez and Hynes (2003) that would be equally applicable in the context of India.

3 Study Area

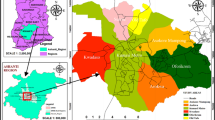

Before introducing our study area (Fig. 3.1)—the land within the Delhi Urban Agglomeration but outside of the Delhi core—a brief account of the concept of the rural-urban dichotomy and the definition of urban agglomeration in the Indian Census is in order. Census of India defines the term “urban” on the basis of a set of criteria (towns and cities) that set them apart from rural areas (villages). Places with a minimum threshold of 5,000 population, 75 % male workers in non-agricultural occupations, and a density of 400 people per square kilometer would qualify settlements as urban.Footnote 4 The urban places are divided into two groups according to their status, namely, statutory towns (ST) (e.g., municipalities, corporations, cantonment board, notified area), and census (or non-municipal) towns (CT). The urban places of over one hundred thousand population (Class I) are termed ‘cities’; rest are termed as “towns” and are divided into five classes on the basis of their population size categories (Classes II–VI).

The urban agglomeration (UA) concept evolved from the initial recognition of the “clustering of municipal and non-municipal localities” or “Town Groups”. Criticized for its ‘lack of spatial cohesion and contiguity,’ the concept of ‘Town Group’ was replaced by that of the Urban Agglomeration in 1971. It was further modified in 2001 when two new criteria that are in effect to this day, were introduced.Footnote 5 The Census of India (2011) defines the Urban Agglomeration thus:

An urban agglomeration is a continuous urban spread constituting a town and its adjoining outgrowths (OGs) of two or more physically contiguous towns, together with or without outgrowths of such towns. An urban agglomeration must consist of at least a statutory town and its total population (i.e., all the constituents put together) should not be less than 20,000 as per the 2001 Census. In varying local conditions, there are similar other combinations which have been treated as urban agglomerations satisfying the basic condition of contiguity. Examples: Greater Mumbai UA, Delhi UA etc.

Delhi Urban Agglomeration (DUA) comprises the three adjoining statutory cities of Delhi Municipal Corporation (DMC), New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) and Delhi Cantonment (DC) at the core (henceforth referred to as Delhi Core/Core) surrounded by [census] towns and outgrowthsFootnote 6 as described above. The DMC, comprising approximately 85 % of the area and 97 % of the population of the Delhi Core, is the primary city of the Delhi Urban Agglomeration (Fig. 3.2). For our purpose we felt that the census-defined Urban Agglomeration is an ideal area for observing the changing characteristics of an urbanizing territory comprising both urban and rural settlements at different points on the urban-rural continuum. Because of their inclusion of the metropolitan core and other statutory cities as well as the census towns and rural settlements under one umbrella, the urban agglomerations offer wide arrays of locational, demographic, economic, jurisdictional, and other attributes to be of interest to urban researchers. Further, because the concept of urban agglomeration has a uniform census definition with clearly specified characteristics, studies such as ours can be extended to other agglomerations in India.

Deciding on an appropriate spatial scale for the study of urban sprawl has remained a challenge for the researchers. As Wolman et al. (2005) noted, in many of the prevalent sprawl studies, ‘over or under-bounding’ of the study area may have led to over or under-estimation of the actual occurrence of sprawl. In response to these problems, they proposed an “Extended Urban Area,” that included the urbanized core, the adjacent urbanized territory, and additional commuting areas linked to the urbanized area. While we were mindful of these concerns in determining our study area, we felt it important to tailor our study design to the Indian situation. First, we decided to exclude the urban core because we felt that the disparity between the average densities in the core and the adjoining territoryFootnote 7 would distort our measure of sprawl. Second, we were especially interested about the demographic transformation of the area within the Urban Agglomeration, but outside of the Delhi Core, and decided thus to limit our focus to only this area. (For the purpose of this paper we will term the study area as AADC or Area Adjoining the Delhi Core). This is an expanding urbanizing territory containing census towns from prior Census decades, as well as new CTs that were uplifted from village to town status by satisfying the minimum census-defined urban threshold criteria during 2001–2011.Footnote 8 Altogether, this area contains 103 census towns with a total population of 4,821,421 concentrated in 35,443.2 ha. Only the contiguous CTs adjoining the Delhi Core were included in our measurement of sprawl index. Although these towns share some common locational attributes by virtue of being part of the Delhi Urban Agglomeration (as well as the more narrowly defined study area) they differ considerably in their area size and population that in our estimation add to the suitability of the AADC as the area of focus for our study.

4 Method

For the purpose of our study we used the density-based Sprawl Index as operationalized by Lopez and Hynes (2003) with some modifications.Footnote 9 As noted in a previous section, much of their arguments in favor of their index (e.g., simplicity, objectivity, census-based etc.) resonated with our purpose. In addition, we felt that the L-H Sprawl Index also met at least two of the 13 suitability criteria advanced by Jaeger et al. (2010) for measurement of urban sprawl, i.e., mathematical simplicity and modest data requirement that would add to its usefulness.

The index is defined as: SIi = (((S % I–D % i)/100) + 1)) × 50

-

Where, SIi is the Sprawl index for metropolitan area i

-

D% is the Percentage of total population in high-density census tracts i

-

S% is the Percentage of total population in low-density census tracts i.

Score values for the index, ranging from 0 to 100, are indicative of the amount of sprawl (high: 50–100; low: 0–50; a score of 50 can be interpreted as equal population distribution in the high and low-density urban situation).

Our calculation of the Index was based on detailed demographic and spatial data from the Census of India for the Census Towns (CTs) and the rural areas surrounding the Delhi Core.Footnote 10 The area of each of the census units was obtained by digitizing unit boundaries on published Census maps from the 2001 Census. The Census maps were also used for identifying the CTs that were contiguous to the Delhi Core and thus included in the calculation of the Sprawl Index. We used the population and area tabulations for each census unit (polygon) and for selected groups of census units providing population totals, and individual and average densities in order to place the CTs into appropriate categories. The high and low density categories were determined by their relative status to the average density for all CTs in the AADC; those with densities lower than the average of the rural units we termed “pseudo urban” and excluded from the computation for the index.

5 Findings and Concluding Thoughts

The results of our analysis are presented in Table 3.1.Footnote 11 Per the index score, the degree of sprawl indicating the concentration and dispersion of population among the low and high-density units increased from the previous decade from 17.5 to 26.76. This is a very modest gain, and in view of the parameters set forth by the authors of the index (Lopez and Hynes 2003), both scores are far down in the 0–100 density continuum. However, viewed from the perspective of a possible urbanization trend, this ten-point gain and the emerging density patterns deserve some attention, especially in combination with the number and distribution pattern of the CTs as apparent in Table 3.1.

In addition to the scores for the Sprawl Index, the table portrays the dispersion patterns of Census Towns across the three levels of density (i.e., high, low, and below-rural), as well as the proportion of total population at the high and low-density CTs. Given the rapid rise of the census towns across the country during the 2001–2011 decade, the fact that the total number of Census Towns almost doubled in a dynamic city-region such as the Delhi Urban Agglomeration was not unexpected. But the fact that the number of low-density CTs (13–135 persons/ha) tripled during this period is relevant to our study and may be indicative of an incremental change towards more low-density settlements in the AADC.

Figure 3.2 depicts the urban spread of cities within the urban agglomeration. The location of the high-density cities closer to the core city supports the idea of the growth-proximity hypothesis. More to the point, the rather scattered pattern of the low-density CTs throughout the rest of the AADC depicts another characteristic of sprawl.

Our current research, based on a single measure of density in context of one urban agglomeration region is intended to be an exploratory study to be construed as a starting point for future research on the multi-dimensional sprawl phenomenon. Our study in the measurement of sprawl index was designed on the basis of easily available census data. We value the utility of the ‘technologically reliant’ methods of measuring urban concentrations and sprawl utilizing GIS/remote sensing data (satellite or aerial). Although arguably less accurate on population count, their ability to use visual images in distinguishing between urban and rural settlement patterns and the potential for many other sources of data interpretations and more frequent sampling of spatial changes make such tools assets to sprawl investigations. Nonetheless, because of its regular and periodic data collection regime, unbiased and uniform data sets on a wide range of social, economic and other characteristics, versatility, and applicability at a wide range of scales, we consider the census to be a highly appropriate data source for sprawl studies in the developing countries. We also maintain that ready availability of the census data diminishes the need for additional data collection cost and that the uniformity of the national census allowing researchers to observe regional variations also enhances their usefulness. Our study demonstrates the potential for using a simple, objective, and measurable density-based index on the use of widely available census data towards understanding the sprawl phenomenon in a developing country, providing us with clues for further research on the multidimensional traits of sprawl, especially in the urbanizing landscape in the context of Mega-city growth.

Notes

- 1.

The growth rates of the Census Towns over the 2001–2011 decade appear to have wide regional variations (e.g., about 90 % of the urban growth in the southern state of Kerala can be attributed to the growth of the Census Towns whose number increased from 99 to 461 during this period).

- 2.

Viewed together, they are remarkable as much for their commonalities, as for their differences. The former underscores an almost intuitive universal understanding of the essence of sprawl, what a sprawl is (reminiscent of the now-famous statement in context of pornography), as well as for an almost universal acceptance of the relevance of density in any consideration of sprawl. The later has arisen primarily due to the differences in the disciplinary backgrounds of the researchers, research focus (e.g., theoretical, empirical, or both), research techniques/variables used (e.g., use of remote sensing/GIS, demographic data, or both), and the perpetuation of the aforementioned ‘semantic wilderness’ (Galster et al. 2001) by including issues such as examples, characteristics, causes, consequences, patterns, and process of sprawl in defining this concept.

- 3.

Lopez and Hynes used their Sprawl Index (SIi) on 330 out of 331 metropolitan areas in the USA., and came to the conclusion that while sprawl increased in many metropolitan areas, there were “important geographic variations in sprawl, implying that it is neither inevitable not universal” (2003, p. 325).

- 4.

Per the Census definition (Census of India 1991, p. 7), some places that do not fully meet the above criteria but show some ‘distinct urban characteristics’ would also qualify.

- 5.

See Ramachandran (1989, p. 112) for a discussion of the concept.

- 6.

Per Census of India (2011), an “Out Growth (OG) is a viable unit such as a village or a hamlet or an enumeration block made up of such village or hamlet and clearly identifiable in terms of its boundaries and location”.

- 7.

The average density of the AADC (136/ha) was much lower than that of the Delhi Core (218/ha) comprising all three units; the gap becomes more noticeable (248 vs. 136) when only the DMC, with 97 % population of the Core, is taken into account.

- 8.

Historically, Indian Census has treated ‘urban’ and ‘rural’ as two distinct dichotomous concepts with clear definitional boundaries. Yet, in the AADC (as in the rest of the country in varying degrees) the census towns symbolize an evolving ‘hybrid’ landscape between urban and rural that can be an argument in favor of a paradigm shift from dichotomy to continuum, as well as for focusing on census towns in future studies.

- 9.

We used Census Towns instead of census tracts that we divided into different density categories. We also decided to use the density status of the CTs relative to the average density of all the CTs and the rural territory to determine our density-threshold. For a discussion of the importance of determining the appropriate density threshold, and the potentials of distortion with up or downward movement of the high/low density threshold, see Lopez and Hynes (2003, p. 334).

- 10.

The method we used in the measurement and characterization of urban sprawl benefits from the use of official Census data gathering. In many countries it is conducted in a well-planned process in a regular, periodic schedule (i.e. decadal as in India and the U.S.). The Census units (polygon areas) are established and used for gathering and reporting the results and may be aggregated to polygons as various levels (e.g., national, state, local political subdivisions). In addition to population count, opportunities exist for gathering a wide variety of social, economic and residential characteristics from census reports thus making it a valuable data source.

- 11.

We had used the L-H Sprawl Index in a previous paper on the same study area (Mookherjee and Hoerauf 2004) in which a computational error resulted the index score for 2001 as 49.5. The correct index score of 17.5 is reported in the present study that is an extension of the previous research.

References

Altieri L, Cocchi D, Pezzi G, Scott EM, Ventrucci M (2014) Urban sprawl scatterplots for urban morphological zones data. Ecol Indicat 36:315–326

Arribas-Bel D, Nijkamp P, Scholten H (2011) Multidimensional urban sprawl in Europe: a self-organizing map approach. Comput Environ Urban Syst 35(4):263–275

Asif K (2014) Encroachment of agricultural land in urban fringe areas of Aligarh City, India: process and parameters. Asian Geogr. http://dx.doi.org/10,1080/10225706.2014.883321. Accessed 18 Feb 2014

Asif K, Rahman H (2013) Land use and socio-economic responses to urban encroachment on agricultural land – a study of an Indian urban-rural fringe. Geograficky Casopis/Geogr J 65(4):289–314

Basawaraja R, Chari KB, Mise SR, Chetti SB (2011) Analysis of the impact of Urban Sprawl in altering the land-use, land-cover pattern of Raichur City, India, using geospatial technologies. J Geogr Reg Plann 4(8):455–462

Bhatta B, Saraswati S, Bandopadhyay D (2010) Urban sprawl measurement from remote sensing data. Appl Geogr 30(4):731–740

Brueckner J (2000) Urban sprawl: diagnosis and remedies. Int Reg Sci Rev 23(2):160–171

Burchell RW, Shad NA, Listokin D, Phillips H, Downs A, Seskin S, Davis JS, Moore T, Helton D, Gall M (1998) The costs of sprawl—revisited. Transit Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Report 39, published by Transportation Research Board, Washington

Census of India, 1991 (1991) Provisional population totals: Paper 2 of 1991. The Controller of Publications, Delhi

Census of India, 2001 (2002) Provisional population totals: Series 8 Delhi, Paper 3 of 2001. Government of India, New Delhi

Census of India (2011) Provisional population totals, Paper 2 of 2011. http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/paper2/prov_results_paper2_indiavol2.html

Coulter P (1989) Measuring inequality: a methodological handbook. Westview, Boulder

Denis E, Mukhopadhyay P, Zerah M-H (2012) Subaltern urbanisation in India. Econ Polit Wkly 47(30):52–62

Ewing RH (1994) Characteristics, causes, and effects of sprawl: a literature review. Environ Urban Stud 21(2):1–15

Ewing RH (1997) Is Los-Angeles-style sprawl desirable? J Am Plann Assoc 63(1):107–126

Ewing RH (2003) Measuring sprawl and its transportation impacts, Transportation Research Records. J Transport Res Board 1831(1):175–183, Paper No. 03-4195

Ewing R, Pendall R, Chen DT (2002) Measuring sprawl and its impact. Smart Growth America/U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC

Fazal S (2001) Application of remote sensing and GIS techniques in urban sprawl and land use change mapping: a case study of a growing urban center in India. Asian Profile 29(1):45–62

Frenkel A, Ashkenazi M (2008) Measuring urban sprawl: how can we deal with it? Environ Plann B Plann Des 35(1):56–79

Fulton W, Pendall R, Nguyen M, Harrison A (2001) Who sprawls most? How growth patterns differ across the U.S. The Brookings Institution, Washington D.C

Galster G, Hanson R, Ratcliffe MR, Wolman H, Coleman S, Freihage J (2001) Wrestling sprawl to the ground: defining and measuring an elusive concept. Hous Policy Debate 12(4):681–717

Harvey RO, Clark WAV (1965) The nature and economics of urban sprawl. Land Economics xli(1):1–9

Hindustan Times/Live Mint & The Wall Street Journal (2012) A six-part series on census towns. www.livemint.com/Politics

Jaeger JAE, Schwick C (2014) Improving the measurement of urban sprawl: Weighted Urban Proliferation (WUP) and its application to Switzerland. Ecol Indicat 38:294–308

Jaeger JAE, Bertiller R, Schwick C, Kienast F (2010) Suitability criteria for measures of urban sprawl. Ecol Indicat 10:397–406

Jat MK, Garg PK, Khere D (2008) Monitoring and modelling urban sprawl using remote sensing and GIS techniques. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf 10:26–43

Kew B, Lee BD (2013) Measuring sprawl across the urban rural continuum using an amalgamated sprawl index. Sustainability 5(5):1806–1828, http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/5/5/1806/pdf

Lang R (2003) Open spaces, bounded places: does the American West’s arid landscape yield dense metropolitan growth? Hous Policy Debate 13(4):755–778

Lopez R, Hynes P (2003) Sprawl in the 1990s: measurement, distribution, and trends. Urban Aff Rev 38(3):325–355

Mookherjee D, Hoerauf E (2004) Exploration and measurement of sprawl in the Delhi urban agglomeration. In: Pacione M (ed) Changing cities. IGU Urban Commission and Strathclyde University Publishing, Glasgow

Nasser HE, Overberg P (2001) What you don’t know about sprawl. USA Today, February 22, pp 1A, 6A–9A

Pradhan KC (2013) Unacknowledged urbanisation: new census towns of India. Paper No. 41035; http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/41035/MPRA. Accessed 24 Sept 2013.

Rahman A, Aggarwal SP, Netzband M, Fazal S (2011) Monitoring urban sprawl using remote sensing and GIS techniques of a fast growing urban centre, India. IEEE J Sel Top in Appl Earth Obs Rem Sens 4(1):56–64

Ramachandran R (1989) Urbanization and urban systems in India. Oxford University Press, Delhi

Satterthwaite D (2007) The urban challenge revisited. Environment 49(9):6–16

Sudhira HS, Ramachandran TV, Jagadish KS (2004) Urban Sprawl: metrics, dynamics and modelling using GIS. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf 5:29–30

Torrens PM, Alberti M (2000) Measuring Sprawl. Paper 27, Center for Advanced Spatial Analysis, University College of London. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1370/paper27.pdf

UN-Habitat (2008) State of world cities. Earthscan, London

Wolman H, Galster G, Hanson R, Ratcliffe M, Furdell K, Sarzynski A (2005) The fundamental challenge in measuring sprawl: which land should be considered? Prof Geogr 57(1):94–105

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Japan

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mookherjee, D., Hoerauf, E. (2015). Is It Sprawling Yet? A Density-Based Exploration of Sprawl in the Urban Agglomeration Region Around the Mega City of Delhi. In: Singh, R. (eds) Urban Development Challenges, Risks and Resilience in Asian Mega Cities. Advances in Geographical and Environmental Sciences. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55043-3_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-55043-3_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Tokyo

Print ISBN: 978-4-431-55042-6

Online ISBN: 978-4-431-55043-3

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)