Abstract

This chapter identifies four significant antecedents of an employee’s willingness to share information on an online Enterprise Social Network in a knowledge intensive organization. Employees with more tenure show a higher willingness to share information. For management it is important to be aware of the importance of recognizing employees’ contributions on the network and to recognize that being present on the network takes time. Finally, the fact that people who feel less involved in the company show a lower willingness to share information reveals a limitation for the success of the project.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

More than 200,000 companies are currently using the Yammer platform, a popular online Enterprise Social Network platform (ESN), similar to Facebook but for professional use. Amongst them 85 % of the Fortune 500 companies. Recently Microsoft announced its intent to take over Yammer for 1 billion dollars. ESNs allow employees to develop a profile and connect with other users for the purpose of information dissemination, communication, collaboration and innovation, knowledge management, training and learning, and other management activities [1]. Other examples of such networks are SocialCast and Salesforce.com’s Chatter. Companies’ worldwide annual IT spending is $2.7 trillion with social computing being a major force driving future spending [2]. ESNs are clearly gaining momentum in companies but they have hardly been studied in academic research.

ESNs are assumed to be valuable. Yammer for example has been said to cultivate a sense of community (e.g. at Deloitte), to lead to better teamwork (e.g. at Ford), to improve informal knowledge flows (e.g. at Suncorp), etc. Global financial services provider Wells Fargo implemented a large-scale social networking platform for over 200,000 of its employees and reported significant productivity enhancements [1]. Companies especially seem to deploy enterprise social network platforms with the goal to improve collaboration among employees within departments and across departments [3]. ESNs can enhance business value as a result of providing quick access to information, enabling new forms of communication and collaboration, improving social relationships (existing and new social ties), and facilitating knowledge sharing and collaboration [4, 5].

When it comes to the adoption of ESNs, it has been observed that ESNs often attract much attention in the beginning but after some time see less and less participation. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the reality of work pushes ESN use to the side so that people pull away from ESN activities and return to their original communication pattern [3]. The conclusion is that, because the value of an ESN depends upon the correct use in the entire enterprise (because of network effects), usage is problematic. The goal of our research project is to identify antecedents of the willingness to share information on an ESN.

Given the space limitations we immediately move to the development of hypotheses in the next section. After that, we shortly explain our research method. Next the research results are presented and we discuss the findings.

Literature Review and Research Model

Knowledge on individual employees’ abilities and motivation to contribute to knowledge networks is very limited [6]. In this paper we intend to get more insight into the antecedents of the willingness to share information. We will consider the recognition given for sharing on the ESN, the involvement in the company, having enough time to use the system and the happiness at work. The level of analysis is the individual employee.

Social exchange theory states that individuals interact with others because they assume that such interaction will give them social rewards such as status and respect [7]. Related to this, the expectancy theories of motivation suggest that people are motivated to act in some way because of the recognition through external rewards satisfying personal needs [8]. McLure Wasko and Faraj [9] investigated antecedents of the number of posts of employees on an online discussion forum. They found that the individuals would contribute more responses if they perceived their participation would enhance their reputation. Similarly, back in 1999 Donath [10] found that building reputation was a strong motivator for active participation in an organizational electronic network. Hence, we put forward the following hypothesis:

-

H1: If an employee is convinced that sharing information on the ESN will be recognized, his/her willingness to share will be higher.

Expressing yourself on social networks puts an employee under public scrutiny. In general, self-disclosure is perceived to be risky [11]. Enterprise social networks are supposed to create more transparency, taking away asymmetrical information, what can change power relations in the company. Also, sometimes people may not follow advices that were given by someone else. The credibility of the latter may be lowered and there are chances they will get defensive [12], as this is touching their identity. These negative effects, however, can be countered through dedication at work, or employee involvement. Past research has linked involvement positively to autonomous work motivation, a factor which recently has been shown to stimulate knowledge sharing in networks [8, 13]. Moreover, employees’ involvement in the organization also increases their efforts to share knowledge as it improves their perceptions of the organizational context [14] and thus lowers the perceived risk of information sharing. Knowing this, we hypothesize:

-

H2: If an employees’ involvement in the company is higher, his/her willingness to share information will be higher.

Sharing information on an ESN takes time. ESNs have been touted as harmful because they can create information overload [5] and selecting the information that is relevant to some employee takes time. Anecdotal evidence suggests employees often stop using an ESN after some time because they feel they should spend their time on their primary task [3]. Consequently, we put forward the following hypothesis:

-

H3: If an employee has the impression that time constraints do not allow him/her to take part in the ESN, his/her willingness to share will be lower.

Finally, happiness or well-being at work has been said to increase participation from employees, which concerns therefore also the rise of communication [15]. In our model, well-being at work can also be seen as a proxy for support from colleagues as this support positively affects employee attitudes at work. Such support has been found earlier to stimulate knowledge sharing [14]. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

H4: If an employee is happier to be working at the company, his/her willingness to share will be higher.

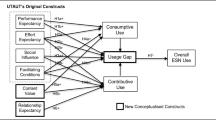

The four hypotheses are shown in Fig. 1.

As shown in Fig. 1, we include two control variables in the model. A first control variable is the average number of other knowledge workers in the organization that a person has contact with per week. This variable may play a role, as it may indicate how open a person is to exchange information with others. On the one hand, a person who is exchanging information with more colleagues in the physical world is probably less closed as a person and more likely to be open to exchanging information with a broader set of colleagues online as well. On the other hand, a person who is sharing information with more people offline probably has a lower necessity to exchange information online. Secondly, the number of years one has been working at the firm may play a role. More specifically, employees with less tenure may feel like they are not the right person to post information and that it is up to employees with more seniority (and presumably more knowledge) to communicate. In fact, prior research in a related field showed that employees with longer tenure contributed more responses on an online discussion forum [9].

Research Setup

The research model was tested in a knowledge intensive organization with 65 knowledge workers. All knowledge workers received an e-mail to fill out an online survey concerning their willingness to participate in an ESN. Employees got one week to reply to the survey. Thirty-one employees did so. 58 % of the respondents were male; 42 % female. Given the small sample size, data was analysed using SmartPLS. SmartPLS is software for path modeling that uses Partial Least Squares.

The items that were used to measure constructs were adapted from prior research including those constructs. For each of the four independent variables and the dependent variable, several items were used. For the control variables, the number of years worked at the company and the average number of people contacted per week, a single item was used. The cross loadings shown in Table 1 do not reveal problems.

Table 2 shows the cross-correlations between the different constructs (with the square root of the AVE on the diagonal). While the correlations between involvement and happiness and between willingness to share and recognition are relatively high, the cross correlations are always lower than the square root of the AVE. Moreover, regressing involvement and happiness against another variable gives a VIF of 2.309, and regressing recognition and willingness to share against another variable gives a VIF of 2.429. This allows us to assume there is no problem of multicollinearity. All in all, there is no reason to expect issues with discriminant validity and multicollinearity.

The square roots of the AVEs shown in Table 2 are clearly above 0.7, and all Cronbach’s alphas were 0.7 or above (not shown in the table), showing that there is no reason to assume problems in terms of convergent validity either.

Research Results

The test results are shown in Fig. 2. The R² of the model is high (0.749).

Hypothesis 1 is supported, showing that employees who believe they would be recognized for sharing information on the ESN would have a higher willingness to share information. Hypothesis 2 is supported as well. Employees who feel more involved in the company show thus a higher willingness to share information on the ESN. The belief that one has enough time to actually use the ESN also has a very positive relation with the willingness to share information, supporting Hypothesis 3. Happiness at work could not be shown to be statistically significantly related with the willingness to post information. The t-statistic for the relation between happiness and the willingness to share was 1.1. The insignificance of the relation may be due to the small sample and this result should be interpreted with caution.

In terms of control variables, the number of years an employee has been working at the company indeed has a positive relation with the willingness to share. The average number of co-workers that an employee contacts per week, on the other hand, could not be shown to be significantly related to the dependent variable.

Discussion

The fact that the model has an R² of 0.749 shows that the antecedents in the model are valuable to explain the variation in the willingness to share information on an ESN. While we are not aware of other research investigating the willingness to share on an ESN, the R² is high compared to similar studies with other applications. For example, in their study of antecedents of the number of posts of employees on an online discussion forum, McLure Wasko and Faraj’s model [9] had an R² of 0.37.

Two very significant antecedents are the recognition one expects to get from superiors and the feeling one has some slack time to spend on the ESN. These findings have big practical consequences, which deserve special attention in the domain of ESNs. The reason for this is the following: the initiative to start an ESN for a company often comes from the business people who feel a need for information from colleagues. It is a requirement that arises at the bottom of the organization, but in contrast to classic IT implementations, the requirement does not need to move bottom-up to get the IT platform installed: ESN platforms are usually run in the ‘cloud’ and offer free versions. Business people have no need (and often don’t want) to get the IT department involved. This implies that the ESN initiative is often not managed at all. While business people who need more information may set up the platform, people who have knowledge to share may have little motivation or time to take part. Consequently, if management is not setting up a kind of reward system and is not admitting that being present on the ESN takes time, the ESN may only be short lived. Moreover, the consequence is that people soon would say ‘we gave it a try, but an ESN did not work’, jeopardizing new ‘managed’ attempts to set up an ESN. Hence, a lack of recognition and a lack of time are serious threats to the use of ESNs. However, management can facilitate the use of ESNs through several possible ways in terms of HR practices (rewards, retention, etcetera) and job design [6].

Although other research showed puzzling findings on the relationship between information sharing and commitment, our results point to the importance of company involvement for knowledge sharing through ESNs. Our results are therefore in line with those of Kalman [16]. People who feel like they work in an exciting firm with an interesting future, which has a project in which they can really play an important role, are more likely to share information on the ESN in order to help their organization forward. This is a property of the company-employee relationship which exists even without the ESN (in contrast to the ‘recognition’ and ‘time’ issues mentioned above, which are related directly to the ESN). Therefore, it may be harder to observe that this variable is playing a role [14] and hence companies may forget to consider this variable in their change management practices. More specifically, the people who feel very involved are likely to be the people who are taking the initiative for setting up the ESN (as mentioned in the paragraph above). They may get frustrated if other employees don’t show the same passion to help the company or they may feel like their efforts are not appreciated. This could lead to less initiative taking in the future. Also, people who feel less involved in the company show a lower willingness to share information, implying that there is likely to be knowledge that remains untapped.

The most positive finding concerns the relevance of the tenure variable. The more years an employee has been working in a company, the higher his willingness to share information on the ESN. This is important, as these are typically the people who have gathered a lot of knowledge on ‘stable’ elements over the years and they are often in a position to have access to ‘new’ elements earlier than others.

In terms of limitations, we stress the fact that our research was conducted in a single institution and a single country and that the research needs to be replicated in other (and bigger) institutions and countries to guarantee the external validity. Also, given the small sample size, it would be inappropriate to conclude that happiness really is not a significant antecedent. Stepping away from ESNs, further research is needed on the way IT implementations need to be managed in the future. Change management has often been problematic in the past, even when companies still had official IT projects that were ‘managed’. Now, with more software running in the cloud, including free versions, initiatives of people who care for the company may fail (because of a lack of change management), with all its consequences.

Conclusions

This paper identifies four significant antecedents of an employee’s willingness to share information on an online Enterprise Social Network. The positive news is that employees with more tenure show a higher willingness to share information. For management it is important to be aware of the importance of recognizing employees’ contributions on the network and to recognize that being present on the network takes time. Finally, the fact that people who feel more involved in the company show a higher willingness to share information reveals a risk for the success of the project which may be harder to manage.

References

Turban, E., & Bolloju, N. (2011). Liang, T-P : Enterprise Social Networking : Opportunities, adoption, and risk mitigation. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 21(3), 202–220.

Gartner (2011). http://www.gartner.com/it/page.jsp?id=1824919.

Li, C. (2012). Making the business case for enterprise social networks. http://www.altimetergroup.com/research/reports/making-the-business-case-for-enterprise-social-networks

Albuquerque, A., & Soarez, A. L. (2011). Corporate social networking as an intra-organizational collaborative networks manifestation. In L. M. Camarinha-Matos et al. (Ed.), PRO-VE (pp. 11–18).

Parsons, K., McCormac, A., & Butavicius, M. (2011). Don’t judge a (Face)book by its cover: A critical review of the implications of social networking sites. Defence Science and Technology Organisation TR, 2549, 39.

Reinholdt, M., Pedersen, T., & Foss, N. J. (2011). Why a central network position isn’t enough: The role of motivation and ability for knowledge sharing in employee networks. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1277–1297.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social Life. New York: Wiley.

Porter, L. W., & Lawler, E. E, I. I. I. (1968). Managerial attitudes and performance. Homewood, IL: Irwin.

McLure Wasko, M., & Faraj, S. (2005). Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 35–57.

Donath, J. S. (1999). Identity and deception in the virtual community. In M. A. Smith & P. Kollock (Eds.), Communities in cyberspace (pp. 29–59). New York: Routledge.

Olivero, N., & Lunt, P. (2004). Privacy versus willingness to disclose in e-commerce exchanges: The effect of risk awareness on the relative role of trust and control. Journal of Economic Psychology, 25(2), 243–262.

Gal, D., & Rucker, D. D. (2010). When in doubt, shout! Paradoxal influences of doubt on proselytizing. Psychological Science, 21(11), 1701–1707.

Vansteenkiste, M., Neyrinck, B., Niemiec, C. P., Soenens, B., De Witte, H., & Van den Broeck, A. (2007). On the relations among work value orientation, psychological need satisfaction, and job outcomes: a self-determination theory approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80, 251–277.

Cabrera, A., Collins, W. C., & Salgado, W. F. (2006). Determinants of individual engagement in knowledge sharing. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(2), 245–264.

Oswald, J. A., Proto, E., & Sgroi, D. (2008). Happiness and productivity, IZA Discussion Paper 4645, 53.

Kalman, M. E. (1999). The effects of organizational commitment and expected outcomes on the motivation to share discretionary information in a collaborative database. Unpublished dissertation, University of Southern California, California.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Leroy, P., Defert, C., Hocquet, A., Goethals, F., Maes, J. (2013). Antecedents of Willingness to Share Information on Enterprise Social Networks. In: Spagnoletti, P. (eds) Organizational Change and Information Systems. Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation, vol 2. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37228-5_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-37228-5_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-37227-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-37228-5

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)