Abstract

The relationship between economic structure and productivity growth has been a subject of increasing interest over recent decades. The innovative focus of this paper concerns the role of the service sector in this relationship at a regional level. Traditionally, productivity has been introduced as explaining factor of tertiarization processes in advanced economies, while it has been simultaneously assessed that services display lower productivity levels and growth rates than other economic industries. Nevertheless, in recent years many papers and authors have refuted or limited these conventional theses.

This paper focuses on the impact of tertiarization on overall productivity growth, using a sample of European NUTS-2 regions in the period between 1980 and 2008. The results partially refute traditional knowledge on the productivity of services. Contrary to what conventional theories suggest, this research demonstrates that several tertiary activities have shown dynamic productivity growth rates, while their contribution to overall productivity growth plays a more important role than was historically believed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Over recent decades, increasing attention has been paid to the relationship between the economic structure of economies and their productivity growth, particularly considering the role being played by service industries. Those pioneer contributions to this topic, during the 1970s and 1980s, focused on two processes. On one hand, “deindustrialization” which started with the economic crisis of the 1970s, trying to explain the continuous growth of service sector in the developed economies compared to the manufacturing decline.Footnote 1 On the other, the progress towards a service society or an increasingly tertiarized society. Footnote 2 The majority of these works underlined that changes involved in a transfer of labour from sectors with low productivity to other more dynamic sectors was one of the main reasons for the overall productivity growth in an economy.

Nevertheless, a wave of economic literature, from the foremost contribution by Fourastié (1949) and, particularly, since the seminal work by Baumol (1967) and their well-known “cost disease”, has supported the thesis that the continuous increase of services in the economic structures as part of the development processes, together with the low productivity in these types of activities as compared with the manufacturing industries, entail a clear threat for future growth, while its rates should be pushed down.Footnote 3

The relationship between the growth of services and labour productivity, comparing different samples of OECD countries and time periods, has been revised in the recent literature. This chapter tries to translate these issues to the regional sphere. Productive specialisation can be one of the main causes of the differences between regionalFootnote 4 behaviour and that of the countries. The evolution of those regions with a higher specialisation in dynamic activities will be far higher than the average of their corresponding countries.

On doing so, two hypotheses were considered. The first discusses what role structural changes play in overall economic productivity and particularly focuses on the growth of services activities. The idea underlying this hypothesis is whether the transfer of labour from less to more productive sectors does or does not propel an increase in the overall productivity of the economy. The second hypothesis tries to verify whether any differences are noted in productivity depending on the different branches of the services sector. Some recent studies have demonstrated this hypothesis confirming that some tertiary branches of the most advanced countries show equal or better productivity levels than those of the manufacturing branches, and therefore demonstrating that they contribute to the overall productivity growth of their respective economies. The paper aims to assess whether a regional analysis allows us to draw similar or identical conclusions to those obtained from those studies based on national data. To be precise, this is not the only concern in this work. It is also being considered the possibility that differences arise and in that case and in that case we should be able to explain them. For this purpose, regions taken as a reference for the analysis are NUTS-2Footnote 5 from a sample of 16 European countries (EU-15 with the exception of Luxembourg, plus Norway and Switzerland) in the period between 1980 and 2008.Footnote 6

The structure of the analysis is the following. Firstly, we set out some theoretical thoughts regarding the relationships between structural changes, services and productivity (Sect. 2). Then, we offer an overview of the results obtained from the application of shift-share techniques both at national and regional level (Sect. 3). Following on from this we will contrast the previous results with estimated econometric data panel models highlighting coincidences and discrepancies (Sect. 4). And, finally, the paper ends with some final remarks on the most significant results and a summary of the questions that have been posed.

2 Structural Change, Service Industries and Productivity Growth in Recent Literature

As mentioned, increasing attention has been recently paid by different authors to the relationship between the economic structure of a country and its overall productivity growth. Along the second half of the twentieth century, those pioneer papers on this subjectFootnote 7 have been followed by others focused on the manufacturing sector.Footnote 8 Nevertheless, the influence of services sector has not been analyzed empirically as much as would have been expected given its dominant role in highly developed countries.

A controversial topic in last decades has been, precisely, the extraordinary increase in the weight of services in advanced economies, as well as its challenges and policy implications. An important aspect is whether this increasing weight of the service industries does have or not an impact on the performance of the overall productivity. Except for some papers (i.e.: Dutt & Lee, 1993; Maroto & Cuadrado, 2007, 2009), this factor has not been dealt empirically in the depth required and only a very few papers have analyzed this problem at regional level and practically all them referred to a single country. This paper aims to contribute to fill the gap and to feed the debate around productivity in service sector from a regional perspective.

Baumol (1967) and himself with the collaboration of Blackman and Wolff (1989) produced some suggestive ideas on the relationship between the progressive growth of services in advanced economies and their low productivity. Nusbaumer (1987) and De Bandt (1991) have also agreed on Baumol’s approach. Using the labour force in order to explain the differences in productivity among industries, such theories concluded that economic growth and overall productivity growth of “service” economies would show a trend to a slowdown. Empirical evidence commonly shows that there is a negative relationship between the overall labour productivity growth and the weight of the services sector in advanced economies. Figure 9.1 shows aggregate evidence on this for a wide group of OECD countries. It can be seen that there is a negative relationship between the overall labour productivity growth rate of the economy and the weight of the services sector.Footnote 9 Data show that the economies having higher productivity growth are also those in which the services sector had a lower percentage of the total at the beginning of the 1980s, as occurs in the case of Korea, Ireland, Iceland, Finland and some of the New Members of the EU. On the contrary, countries showing a high percentage of services (in total production and employment) register lower productivity growth rates, as it is the case of Italy, Germany, Canada, the Netherlands, Spain or the United Kingdom. The only exceptions in this Fig. 9.1 are countries such as some Nordic (Sweden or Denmark) or the United States.

Relationship between service sector weight (and productivity growth 1980–2008. OECD countries sample. Source: Own elaboration. Data Conference Board (2011) and OECD (2009)

The latter affirmation was based on the hypothesis of a lower productivity growth within the services sector. But, in recent years this thesis has been smothered or even refuted by empirical evidence in some papers. Even Baumol (2002) rectified his previous position by admitting that it is necessary to differentiate between types of services and stressing the role of innovation and knowledge in the evolution of services. Triplett and Bosworth (2006) have also criticized the traditional theories on the services sector and even believe they have found the “cure” for Baumol’s cost disease. Generally speaking, criticism and revision are based on the following components (Maroto, 2012): (1) the need to take into account the indirect effects of some service activities on the productivity growth within other industries; (2) biases in the definition and measurement; or (3) the possibility of using indirect indicators of productivity as consequence of the conceptual and statistical debates generated over the last 10 years.

Some empirical studies have proved that the traditional affirmation that services contribute to the stagnation of overall productivity growth in the long term might actually be questioned. The data at international level highlight the patterns of dynamic productivity in some branches of services, mainly those related to ICT, both in Europe (O’Mahony & van Ark, 2003; van Ark & Piatkowski, 2004) and in the US (Bosworth & Triplett, 2007; Stiroh, 2001; Triplett & Bosworth, 2004). The high growth rates have been almost continuous over the last decades, fact which suggests that these service industries do not seem to be asymptotically “stagnant”. On the contrary, the dynamism observed in some advanced economies from the middle of the 1990s may indicate an environment for potential improvements in the future.

Additionally, the theories which currently explain the reason for the growth of services and which condition their productivity are not limited exclusively to the labour factor, but are related to multiple factors, such as those linked to the nature of the services, the organization and segmentation of their markets, or the special substitution relationships between labour and capital (Rubalcaba, 2007). Finally, others authors have highlighted the interrelationship between globalization, trade and growth of services (Cuadrado et al., 2002).

Empirical evidence summarized in Table 9.1 shows that productivity growth in relation to the evolution of employment and production is not homogeneous in all service branches. Communications and some branches of transport show high productivity growth rates, although without regard for strong employment reduction processes. On the other hand, part of the transport services, the financial activities, wholesale trade and renting services are characterized by an intensive use of factors boosting productivity, such as innovation or human capital. All of them show also positive employment growth.

3 Structural Change, Service Sector and Productivity Growth: A Decomposition Analysis

3.1 Data and Methodological Approach

European Regional Database provided by Cambridge Econometrics will be used in order to develop our analysis. It offers indicators on gross value added, employment and other relevant economic variables both for countries and regions at a sector level since the beginning of the 1980s. Despite the narrow industrial disaggregation of this source, we have chosen it due to the homogeneity with the other sections in the paper. The sample of countries used includes all of the EU-15 with the exception of Luxembourg, plus Norway and Switzerland. The time span used is the one available in the chosen source, which ranges from 1980 to 2008. Finally, the selected breakdown by economic sectors is as follows: agriculture (01–05 level of the ISIC), manufacturing and mining (10–39), construction (45), market services (50–74), and non-market services (75–99). As service sector constitutes the focus of our analysis, market services have been broken down into five branches: distribution (50–52), hotels and restaurants (55), transport and communications (60–64), financial and insurance services (65–67), and other market services, including real state and business services (70–74).

To analyze what is the impact of structural changes on the productivity growth we will use the data above described, pointing out the heterogeneity of the different branches within service sector. To do it, a shift-share type analysis is used. This technique provides a convenient tool to research how aggregate growth is mechanically linked to differential growth of labour productivity and the reallocation of labour between industries. It breaks down overall productivity growth into two effects: structural changes (net or static effect and dynamic effect) and the within-sector productivity growth. Formally, the method applied here may be derived as follows:

where: π is the labour productivity; t-n is the initial year; t is the final year; i corresponds to each economic sector; r to regions, and s is the sector weight in terms of employment \( {s_i}=\frac{{{L_i}}}{L} \).

According to the methodology, the overall growth of labour productivity can be broken down into three differentiated effects. The first is the contribution from changes in the allocation of labour between industries. The second one measures the interaction between changes in productivity in individual industries and changes in the allocation of resources. Finally, the third effect would be the contribution of productivity growth within individual industries (weighted by the share of these in total employment).

Decomposition techniques do not just allow us to analyse structural changes over time and their effects on productivity, but also structural changes in space and their effects. For this purpose, we have used a decomposition technique (shift-share) in order to analyse the regional productivity growth (and the variables it depends on: production and employment) by using two effects of a multiplicative natureFootnote 10: the country effect (CE) and the net effect (NE) of the region. The latter can also be broken down into the product of the proportional effect (PE), based on the productive structure of the region, and the differential effect (DE), which represents the rest of the identifying variables of the region itself. Although Eq. (9.1) will be used for both the analysis by countries and by regions, the technique described below will only be used for the regional analysis.

Each index or effect can be greater than one (if the region has grown above national average) or lower than one (otherwise). The mathematical expression in the analysis of production and employment would be as follows:

where ξ represents the analysis variable (gross value added, Y, or employment, L), i represents the N productive sectors, r corresponds to the regions considered, and t and t-n are the two points of time chosen in the analysis (1980 and 2008).

Regional productivity growth can be obtained from the previous equations as the quotient between the growth of gross value added and regional employment. The aforementioned productivity growth π can be broken down again into its country, proportional and differential effects, on the basis of the following equation:

In accordance with formulas (9.2) and (9.3), a region r can be classified according to six different typologies or categories, three with a NE greater than one and three with a NE lower than one:

-

1.

NE, PE, DE > 1: Dynamic regions.

-

2.

NE, PE > 1, but DE < 1: Regions specialised in dynamic sectors.

-

3.

NE, DE > 1, but PE < 1: Regions with advantages of location.

-

4.

NE, PE, DE < 1: Backward regions.

-

5.

NE, PE < 1, although DE > 1: Regions specialised in backward sectors.

-

6.

NE, DE < 1, although PE > 1: Regions with disadvantages of location.

3.2 National Results

According to Eq. (9.1), results of national calculations for the period 1980–2008 are shown in Table 9.2, both for the countries belonging to the Euro-zone and to the sample of 176 OECD economies, broken down into individual contributions by the three main economic sectors. Table 9.3 shows analogous results broken down by specific service industries. In line with the Eq. (9.1) on the breakdown of the overall productivity, the sum of the static and dynamic effects, as well as the within-industry growth, is equal to the average growth rate of labour productivity in the according aggregate (first cell in each sub-table). This is how the data sums up horizontally. Vertically, for each of the three components, the contributions made by each sector also sum up to the corresponding number in the first line of each sub-table. As additional information, the number in brackets show the average growth of labour productivity within individual sectors or service industries(Table 9.3), and don’t sum up neither in the horizontal nor in the vertical dimensions. They facilitate us the work of identifying whether there are any regular patterns of differential productivity growth between industries.

Supported by data from Table 9.2, some stylized facts can be underlined. First of all, the structural components emerge to be generally dominated by the within effects of productivity growth, which is consistent with the results obtained by some authors and referring to other economic areas.Footnote 11 This means that, in aggregated terms, the reallocation of labour among those sectors with low and high productivity has only had a weak net effect on overall growth. This fact is even more noteworthy since the mid-1990s, a period in which productivity growth rates of the European countries in relation to other areas, such as the US, began to fall notably. Secondly, it can be seen that there are not significant differences between the two areas analyzed. Euro-zone performance differs somewhat from the case of the broader sample, where the productivity growth rate is a little bit higher (due to the higher productivity growth rates experienced in most of Northern European countries) and the structural effects, both static and dynamic, are barely lower than in Euro-zone countries. Thirdly, the data obtained show the simultaneous operation of opposing mechanisms captured under the static and the dynamic shift effects. The structural burden of resource reallocation seems to be robust in the European case, where the dynamic effect is negative for the broad 3-sector break down. Finally, if we analyze the performance by sectors, most of the effects on the overall productivity come from non-tertiary activities. This suggests that, despite the progress obtained as regards productivity by the services sector, those non tertiary activities are still providing the major contribution to the growth of the overall productivity of the advanced economies.

This aggregated approach could conceal important structural aspects in each individual sector. This perspective is particularly interesting in the case of the service sector, where the overall contribution to productivity is divided practically between two of the components analyzed here: the within growth and the static effect. In other words, services contribute to GDP per capita via two different channels. Firstly, through their within growth of the GDP per hour worked, just as in any other sector and secondly, and this is an exclusive factor of services sector, through the growth of the weight their activities suppose in terms of employment. This is consistent with the traditional hypothesis on growing percentages in the demand for the services sector due to its greater income-elasticity.Footnote 12

If we deep into the service sector (Table 9.2), calculations show that productivity growth of the service sector in the sample of 17 advanced countries (0.83 per 100) is rather higher than the growth in the Euro-zone (0.60 per 100) and both rather distant from the one in the US (1.3 per 100). But, disaggregating the heterogeneous branches of services, there are some, particularly transport, communications and financial services, which show high within growth (last column), similar to those within sectors traditionally characterized by higher productivity levels. Moreover, most of the productivity growth comes from the reallocation of resources and not from the within growth. Consequently, the traditional view of the (aggregated) service sector being scarcely productive might be refuted when certain tertiary activities are studied, consistent with the findings of some of the more current empirical studies. Again, the case of the Euro-zone differs to some extent from the broader sample of 16 countries. Additionally, detailed analysis of these data shows, as in Table 9.1, that structural burden hypothesis is clearly confirmed for the service sector in the Euro-zone, although the effect in the EU16 is null. Alternatively, the structural bonus hypothesis (positive static effect) can also be observed—with few exceptions—in most service industries.

The results presented are consistent with those found by other authors for previous periods (Bonatti & Felice, 2008; Fagerberg, 2000; Maroto & Cuadrado, 2007, 2009; Peneder, 2002, 2003; van Ark, 1995). The structural change Footnote 13 has a positive effect, although this is relatively weak, on the overall productivity growth. No clear or univocal tendency to the reallocation of labour to those sectors with higher productivity levels has been found. However, the robust existence of a so-called structural burden can be observed due to the fact that, in the sectors with faster productivity growth, the expansion of production is not generally accompanied by growth in employment. Thus, it is possible to speak about a stylized fact. In contrast with periods previous to the economic crises of the 1970s, the results of the period analyzed here show that the structural changes do not notably boost productivity growth. The novelty of our results emerges, neither from the methodological approach used nor from the main conclusions arisen, but from the disaggregated focus of the service industries, clearly characterized by a heterogeneous composition of activities. This will extend findings of previous papers on the service sector, the most important agent in advanced economies.

3.3 Regional Results

The previous section revealed the relationships between structural changes and, particularly, the growth of the services sector and the evolution of aggregate productivity in the European countries. However, the objective of this section is to demonstrate the degree of influence of productive specialisation on the evolution of regional productivity in Europe, paying special attention to the role played by the growth of services.

Productive specialisation can be one of the main causes of the differences between regionalFootnote 14 behaviour and that of the countries. The evolution of those regions with a higher specialisation in dynamic activities will be far higher than the average of their corresponding countries. The main objective of this section is to analyse the importance of these factors, where the contribution of services activities to growth is particularly significant. The main conclusion drawn is that services play a role in the growth of productivity in the European regions under consideration. In order to reach this conclusion, the decomposition techniques described in Eqs. (9.2)–(9.4) are used.

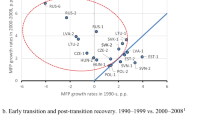

The starting hypothesis of this work was the existence of a positive relationship between the weight of the services sector and the evolution of productivity in the European economies. The previous section revealed the first evidences at a state level. This section tries to draw the same conclusion at a regional level. By using the concept of Camagni and Cappellin (1985), which we previously applied in order to create Fig. 9.1 in Sect. 1, we try to analyse the evolution of labour productivity in a certain European region, together with the evolution of production (added value) and employment of such a region, taking the average behaviour of the country where each region belongs to as a reference. For this purpose, we consider the regional net effects—once isolated from the country effect.

The aforementioned allows us to simplify the information included in the previous tables by classifying the European regions into four different groups or typologies: (1) dynamic regions with net effects greater than one regarding productivity and employment; (2) regions under reconstruction through employment (dynamism regarding productivity arises mainly due to net effects lower than one regarding employment); (3) creation of employment-intensive regions (the net effect greater than one regarding employment leads to a lower growth regarding productivity); and, finally, (4) backward regions (which show a lower growth regarding both productivity and employment).

Map 9.1 shows this classification for the regions analysed during the 1980–2008 period. It is difficult to draw general conclusions from the data obtained due to the high level of heterogeneity between the 170 regions included in the sample since behaviours and explaining factors of a different nature and origin are intertwined. However, European regions can be classified, in a broad outline, according to their productivity growth and their capacity to simultaneously create employment or not.

Regional clustering according productivity and employment, 1980–2008. Note: Black coloured regions identify dynamic regions; beige coloured regions recognize restructuring regions; light grey coloured categorize labour intensive regions; and, finally, dark grey coloured regions classify backward regions. Source: Own elaboration. Data: Cambridge Econometrics

Thus, dynamic regions (those with good results regarding both productivity and employment) are concentrated in some capitals and financial centres, such as Zürich, Lazio, Oslo, Stockholm or Luxembourg, as well as in some small developing outlying regions, such as Algarve, Limburg, Utrecht and the Greek Islands. Some regions belonging to the group of developing European regions of Spain (Extremadura, Galicia, Castile-La Mancha and Castile and Leon), Portugal (Alentejo), Germany (Sachsen, Sachsen-Anhalt, Thuringen and Brandemburg) and Greece (Ipeiros, Dytiki Ellada and Ionia Nisia), as well as some capitals (Paris, London and Brussels) have also registered a dynamic net effect regarding productivity. However, the positive results of productivity achieved by these regions are mainly due to processes of low creation, or even destruction, of employment.

On the other hand, some French (Lorraine and Picardie), Dutch (Drenthe and Groningen) and German (Berlin, Bremen, Hamburg and Saarland) regions, as well as some others from the North of Scandinavia (Ovre Norrland, Sor-Ostlandet, Nord-Norge and Smäland) and the western area of Ireland, the North of the United Kingdom and some Greek regions (Dytiki Makedonia and Sterea Ellada) show a deterioration, because they have registered regional net effects below the national average regarding both productivity and employment.

Finally, some Spanish (Madrid and Catalonia), German (Schlasung-Holstein, Hassen, Baden-Württenberg, Niedersachen, Rheinland-Pfatz and Nordrhein), British (Wales and Yorkshire), French (Provence) and Portuguese (Lisbon) regions do not register good results regarding productivity either. However, this fact is due more to dynamic net effects regarding employment than just to a lack of productivity or efficiency.

Data obtained with this methodology allow us to highlight several stylised facts. Firstly, there is a reverse relationship between the behaviour of regions regarding productivity and employment, although the relationship between productivity and economic growth is positive.Footnote 15 Regions which have created employment to a greater extent in recent decades are generally associated with lower growths of productivity. More specifically, the correlation coefficient between the growth of employment and the growth of productivity in the sample of analysed regions is −0.226 (with a p-value of 0.000), while the correlation coefficient between the growth of productivity and the growth of added value is 0.570 (which is also statistically significant for any significance level). When only the services sector is taken as a reference of employment and production compared to the productivity of the region in question, the results obtained are similar.

However, the relationship between the evolution of productivity and the growth of the weight of the services sector, regarding production and employment, is significantly positive (with a correlation coefficient of 0.151), though not very high. Data seem to show a slight relationship between the weight of services and the growth of productivity in the regions under analysis during the period from 1980 to 2008. This is an important conclusion as it coincides with what was obtained in the previous Sect. 3.1 regarding the national analysis, but even more so because it can be used as a link and foundation for the econometric analysis constituting the core of Sect. 4. The objective of that Sect. 4 is, precisely, to statistically contrast the existence of the aforementioned relationship between the growth of the weight of services in European regions and the evolution of their productivity.

4 Tertiarization and Productivity Growth: An Econometric Analysis

The results obtained until now should not be taken as an implication that the structural changes or growth of services do not play an important role in the evolution of overall productivity. What they do show is that structural changes, on average, do not involve significant growth in that area. One economic sector that deserves an in-depth analysis in this respect is the service sector. Based on this fact, we will analyze the impact of the growth of services on overall productivity growth in the sample of seventeen European countries since 1980. From a merely accounting point of view (as in Table 9.2), some service industries are characterized by both high productivity levels and high growth rates. Nevertheless, the methodology developed previously does not obtain the indirect effects that the tertiarization of the economies have on other sectors (outsourcing, off-shoring, etc.), and maintains the intrinsic difficulties concerning definition and measurement.

4.1 Data and Methodology

To develop this analysis the European Regional Database provided by Cambridge Econometrics will be used again in order to homogenize our results with those in the previous section. However, as previously mentioned, this source only provides information on production, employment and physical capital. In order to complement those items and to explore some additional explanatory factors the Regional Database provided by the OECD will be used as well. The only disadvantage of using both sources is the different time range. While the data base provided by Cambridge Econometrics begins at 1980, the starting date in the one provided by the OECD is 1995, reducing the size of the sample.

The aim of this section will be to explore to what extent an increase in the share of resources assigned to the service industries is relevant to the productivity growth of an economy at a regional level. To achieve this, a panel data model was used, carrying out regressions of the overall productivity growth over the change in the weight of services. Additionally, two other explanatory variables are included: the initial level of productivity (introduced to achieve catching-up or technological convergence) and the initial weight of the service sector (which distinguishes between those countries (regions) which, while undergoing equal growth in the percentages of employment, differ significantly in their levels or weight). As overall productivity growth is also influenced by other variables, besides structural change, a matrix of auxiliary conditioning variables has also been included in the regressions. This matrix includes the investment effort (measured as the ratio between the gross stock of physical capital over GDP), the demographic composition changes (as the relationship between active and total population), the level of human capital (approximated through the percentage of employees with secondary and higher education in the total employment), and the degree of trade openness of the country which each region belongs to.

The final specification of the model to be used is the following:

where i = 1.2,…,K are the regions in the sample (with K = 170), n is the length of the period considered (with n = 28), s i is the weight of the service sector (over total employment) in the country i, and \( \Delta {\pi_i} \) represents the labour productivity growth rate. Z i is the matrix of auxiliary variables. \( {\upsilon_i} \) is the random effects component, and \( {\varepsilon_{it }} \) the residue of the model. The idea of fixed effects is discarded despite its generalised use in panel data models, as this does not admit within-group constant variables, such as the case of the initial weight of the service sector or the initial productivity level in our analysis.

4.2 National Results

Table 9.4 summarizes the main results of the model used.Footnote 16 A simpler model relates the growth of overall productivity only to services growth (column 3.1). Then we have added the initial level of productivity (3.2) and the initial level of tertiarization (3.3). Finally, the matrix of auxiliary variables was included in our model (3.4). The main result is that the increase in the weight of services, from 1980 to 2008, had a positiveFootnote 17 effect on overall productivity growth. However, this positive effect is limited. An absolute increase of 1 per 100 in the weight of the service sector in terms of employment would be associated to an increase of 0.3 points in the rate of absolute overall productivity growth (during the whole period). The estimations are highly significant (at 1 %) and stable throughout the different specifications of the model.

Convergence or catching-up effect (approximate for the level of labour productivity in 1980) is also statistically significant, with a negative coefficient, as predicted by the traditional theories, although this is relatively low. Those countries which started with higher levels have seen how their overall growth rates were below those which were further behind at the end of the 1970s. Additionally, the weight of services at the beginning of the period is also statistically significant and demonstrates a positive sign. This fact may support the hypothesis that those countries which were more tertiarized from the beginning had a more dynamic overall productivity growth rate than those which started with a lower weight of services.

One of the features that characterizes the service sector is a marked heterogeneity (as observed, among other results, in the calculations shown in Fig. 9.1 and Table 9.2), as well as its atomization and diversification of supply due to the fact that market activities and other non-market services coexist in this sector. Consequently, it is reasonable to suppose that the likely impact on overall productivity growth might differ depending on the different kind of services involved. In order to differentiate the results obtained so far depending on service clusters, bottom-block in Table 9.4 shows the results of our model. The innovation is the way in which we distinguish between market and non-market services.

The results highlight that, following the logic stated above, the market services have a higher (and statistically significant) coefficient than that observed in the case of the non-market services. Thus, an increase of 1 % in the weight of market services would suppose an increase in the absolute overall productivity growth amounting to 1.2 % points, whilst the same increase in those services outside the market involves a relatively lower change amounting to 0.45 % points. Additionally, the performance of the other variables included in our model follows the same behaviour patterns as when the service sector as a whole was analyzed in up-block in Table 9.3.

4.3 Regional Results

Table 9.5 summarizes the main results of the model with a panelFootnote 18 of regional data belonging to the 17 European countries of our sample. A simpler model relates the growth of overall productivity only to services growth (column 3.1). Then we have added the initial level of productivity (3.2) and the initial level of tertiarization (3.3). Finally, the matrix of auxiliary variables was included in our model (3.4). The main result is that the increase in the weight of regional service sector, from 1980 to 2008, had a positive effect on overall productivity growth. An absolute increase of 1 per 100 in the weight of the service sector in terms of regional employment would be associated to an increase of 1.1 points in the rate of absolute regional productivity growth (during the whole period). The estimations are highly significant (at 1 %) and stable throughout the different specifications of the model. The explanatory capacity of the model, through its adjusted R-squared, is also relatively acceptable. Moreover, regional results not only argue with previous country ones, but the positive coefficient is even a little bit higher.

The positive relationship between service growth (regressor) and labour productivity (dependent variable) might be endogenous, so results could be influenced by reverse causation matters. In order to solve this, Granger causality testsFootnote 19 were implemented (Granger, 1969). According to our data, the growth of services could explain productivity growth (with the usual number of lags up to 14, null hypothesis that growth of services does not cause productivity growth will be rejected with any usual level of statistical confidence). Nevertheless, reverse causality will not be accepted (null hypothesis that productivity growth does not cause growth of services will not be rejected with any usual level of statistical confidence). Summarizing, likely reverse causation matters seem to be solved in the model regressed here.

Related to the other explanatory variables of the model, convergence or catching-up effect is also statistically tested in the model, although its role is quite low. Those regions which started with higher levels have seen how their overall growth rates were below those which were further behind at the end of the 70s. Additionally, the weight of services at the beginning of the period is also statistically significant and demonstrates a positive sign.

With respect to the auxiliary matrix, and taking into account its incorporation into the model as a complement to the central analysis, all ancillary variables are statistically significant and have a positive coefficient. Both physical and human capital, measured in this analysis as levels, in line with various papers which stress the role of these two factors in economic growth and in the good performance of the productivity growth, have a positive impact on the growth of overall productivity. This is greater in the case of physical capital. Those regions with a greater quantity of qualified working population and more extended capitalization processes are those which have presented a more dynamic growth in productivity. Additionally, demographic issues and the degree of openness of the countries where regions are located also boost productivity growth. Finally, results of the last column in Table 9.3 show that the positive effect of structural changes, and particularly of the services sector growth, is lower when other auxiliary variables are included in the model. This does imply a lower effect of tertiarization on the productivity growth since the mid-1990s. While this effect accounted for 1.1 in the 1980–2008, the relative coefficient was only up to 0.6 when we analyze only the 1995–2008 period. This result follows some of the most recent works in the literature. The role of structural changes over the productivity growth in advanced economies has lost its major role for the within productivity effects since the 1980s (Cuadrado et al., 1999). However, the responsibility of tertiarization, and specially the growth of some professional and dynamic market services since the mid-1990s, has played an important role in the productivity growth of these economies.Footnote 20

Following the schedule applied in the previous section and looking for differentiating the results obtained so far depending on market and non-market services, Table 9.6 shows the results of our model. The results highlight that, following the logic stated above, the market services have a higher (and statistically significant) coefficient. In those non-market services, the behaviour is quite the opposite. Thus, an increase of 1 % in the weight of market services would suppose an increase in the absolute overall productivity growth amounting to 0.61 % points, whilst the same increase in those services outside the market involves a relatively lower change amounting to 0.43 % points. Additionally, the performance of the other variables included in our model follows the same behaviour patterns as when the service sector as a whole was analyzed in Table 9.3.

5 Final Remarks and Open Research Issues

As established in the introduction, the two starting hypotheses of this paper were related to the impact of the growth of services on the evolution of productivity. The first entailed the verification of the role played by structural changes, and particularly the growth of services, on the evolution of economic productivity. The second determined whether the variety of services branches demonstrated different behaviours in this field, in contrast to what has been considered by some more traditional approaches. Furthermore, the preparation of this paper has been inspired by two facts. On the one hand, the results obtained in a recent article (Maroto & Cuadrado, 2009), which showed that structural change has played an important role in the evolution of productivity in a wide sample of developed countries. And, on the other hand, to verify if this is also the same at a regional level, due to services playing an increasingly important role, although there are notable differences among regions.

The analysis by countries, which has been replicated taking 17 European economies as a reference and using data for a substantial period of time (1980–2008), does not produce different results from those obtained in the previous study based on a sample of OECD countries from 1980 to 2005. Conventional theory regarding the relationships between the services sector and labour productivity, according to which the expansion of the former would cause a lower growth of such productivity, cannot be supported in absolute terms. Some services branches register an increase in productivity which is comparable to, or even higher than the one corresponding to manufacturing, although those services branches characterised by a high and irreplaceable use of labour register comparatively low productivity levels.

At a regional level, the results obtained from the sample of 170 European regions during the same period (1980–2008) lead us to conclude that structural change still plays a significant role in the improvement of productivity of each region as a whole. However, as verified at a national level, most of the growth of productivity was due to the improvement within each activity branch and not just to the reallocation of resources between the various sectors.

The shift-share analysis used allowed us to break down the productivity growth in the regions into two components of a multiplicative nature: the country effect and the net effect of the region itself. The latter can also be broken down into the product of the proportional effect and the differential effect. The calculations made have shown that regions can be classified into different categories according to the results of the net, proportional and differential effects. Data obtained have been simplified in order to form four categories or groups of European regions, as illustrated in Map 9.1. Despite this synthesis effort, there is a great heterogeneity in the evolution of the different regions, because of the influence of many behaviours and different factors. However, the analysis reveals that the most dynamic regions are concentrated in various large capital cities and European financial centres, as well as in some outlying regions and regions of a lower weight, some of these related to the growth in tourism. Other comparatively backward regions, where structural change has boosted the increase of productivity to a greater extent than in the most developed regions, must be included.

The econometric analysis carried out has added some interesting results related to the role played by services. It has been demonstrated that the growth of services and productivity is positive and significant. Moreover, it has been verified that there is a process of convergence regarding productivity between those regions registering higher productivity levels at the beginning and the more backward regions. It is also confirmed that those regions specialising in services to a greater extent also register more positive dynamics regarding productivity growth. And, finally, as was expected, those services branches subject to market conditions have a greater impact on the variation of productivity, and this is contrary to the case of non-market services.

This analysis leaves an open door for further exploration of some analytical possibilities. Firstly, the differentiated behaviour of regions must be analysed in more depth and more detailed explanations must be pursued. Furthermore, it seems necessary to verify if the training levels of population—human capital—have an influence on productivity and to what extent. And, finally, a method to delve deeper into the issues considered could be to focus on significant countries or, as an alternative, to make a detailed analysis of those regions included in some of the aforementioned categories.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

In the case of Germany and the United Kingdom, we have used NUTS-1 because the dimension of NUTS-2 is too small to make a realistic and accurate comparison. Additionally, Azores Islands (POR), Ceuta and Melilla (SP) and the overseas French territories have been excluded. In the case of Greece, all islands are considered as a single region.

- 6.

Although the dataset provided by Cambridge Econometrics show estimations for later years, these are only forecasting data. For this reason, in this chapter we have decided to handle the data until 2008.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

Specifically, the correlation coefficient in the case of employment is −0.5223, significant to 1 % (p-value = 0.0040). Results are robust if the weight of service sector is measured in terms of value added. Then, the correlation coefficient is −0.5838, also significant to 1 % (p-value = 0.0015).

- 10.

Instead of the additive nature which is usually used in this kind of techniques. The reasons are: on the one hand, the elimination of effects of scale originated from the use of several variables with different units. On the other hand, the possibility of combining the three variables under consideration: productivity, added value and employment, in just one indicator, in line with what was previously shown graphically in Fig. 9.1.

- 11.

See: Peneder (2002, 2003) for 28 countries of the OECD; Havlik (2005) for the new Eastern European countries belonging to the EU; Fagerberg (2000) for the manufacturing sectors in 39 countries based on the UNIDO; Timmer and Szirmai (2000) for the manufacturing sectors of four Asian countries; Maroto and Cuadrado (2007, 2009) for Spanish economy, and EU-15 and US, respectively; and van Ark (1995) for a group of 8 countries of the EU and the USA.

- 12.

- 13.

This combined effect of the static and dynamic components is named “structural effect” or simply the “effect of structural change” by some authors (Maddison, 1996), and analyzed together although the analysis is deeper if both effects are distinguished.

- 14.

- 15.

- 16.

A standard OLS regression model in a cross-section (for example, in Fagerberg, 2000) has also been implemented. Conclusions, although calculations are not included in the text, do not differ from the conclusions drawn in the paper based on a panel-data regression model.

- 17.

The positive relationship between service growth (regressor) and labour productivity (dependent variable) might be endogenous, so results could be influenced by reverse causation matters. In order to solve this, Granger causality tests were implemented (Granger, 1969). According to our data, the growth of services could explain productivity growth (with the usual number of lags up to 14, null hypothesis that growth of services does not cause productivity growth will be rejected with any usual level of statistical confidence). Nevertheless, reverse causality will not be accepted (null hypothesis that productivity growth does not cause growth of services will not be rejected with any usual level of statistical confidence). Summarizing, likely reverse causation matters seem to be solved in the model regressed here.

- 18.

A standard OLS regression model in a cross-section (for example, in Fagerberg, 2000, or Maroto & Cuadrado, 2009) has also been implemented. Additionally, estimations with subsamples and different time spans have been developed. Conclusions, although calculations are not included in the text, do not differ from the conclusions drawn in the paper based on a panel-data regression model.

- 19.

A time series X is said to Granger-cause Y if it can be shown, usually through a series of F-tests on lagged values of X (and with lagged values of Y also known), that those X values provide statistically significant information about future values of Y.

- 20.

See, among others, Bosworth and Triplett (2007) and Triplett and Bosworth (2004) for the United States; Crespi et al. (2006) for the United Kingdom; McLachlan et al. (2002) for Australia; Maroto and Cuadrado (2009) for a simple of OECD countries; and Maroto and Rubalcaba (2008) for the European Union.

References

Amiti, M. (1999). Specialization patterns in Europe. Review of World Economics, 135(4), 573–593.

Baumol, W. (1967). Macroeconomics of unbalanced growth. The anatomy of urban crisis. American Economic Review, 57(3), 416–426.

Baumol, W. (2002). Services as leaders and the leader of the services. In J. Gadrey & F. Gallouj (Eds.), Productivity, innovation and knowledge in services (pp. 147–163). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Baumol, W., Blackman, S. A., & Wolff, E. N. (1989). Productivity and American leadership: The long view. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bell, D. (1974). The coming of post industrial society. London: Heinemann.

Blackaby, F. (1978). Deindustrialisation. London: Heineman.

Bonatti, L., & Felice, G. (2008). Endogenous growth and changing sectoral composition in advanced economies. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 19, 109–131.

Bosworth, B., & Triplett, J. (2007). The early 21st century US productivity expansion is still in Services. International Productivity Monitor, 14(Spring), 3–19.

Camagni, R., & Capellin, R. (1985). La productivité sectorielle et la politique régionale. Bruselas: Comisión Europea.

Carree, M. A. (2003). Technological progress, structural change and productivity growth. A comment. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 14, 109–115.

Chung, W., & Denison, E. (1976). How Japanese economy grew so fast: The sources of post-war expansion. Washington DC: Brookings Institution.

Combes, P., & Overman, H. (2003). The spatial distribution of economic activities in the EU. In V. Henderson & J. Thysse (Eds.), Handbook of urban and regional economics. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Crespi, G., Criscuole, C., Haskel, J., & Hawkes, D. (2006). Measuring and understanding productivity in UK market services. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 22(2), 186–202.

Cuadrado, J. R., Garcia, B., & Raymond, J. L. (1999). Regional convergence in productivity and productive structure: The Spanish case. International Regional Science Review, 22(1), 36–54.

Cuadrado, J. R., Rubalcaba, L., & Bryson, J. (2002). Trading services in the global economy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Daniels, P. W. (2004). Reflections on the “old” economy, “new” economy, and services. Growth and Change, 35(2), 115–138.

De Bandt, J. (1991). Les services. Paris: Productivité et prix. Economica.

Denison, E. (1967). Why growth rates differ: Post-war experience in nine western countries. Brookings Institution: Washington D.C.

Dutt, M. J., & Lee, K. H. (1993). The service sector and economic growth: Some cross-section evidence. International Review of Applied Economics, 7(3), 311–329.

Ezcurra, R., Pascual, P., & Rapun, M. (2006). The dynamics of industrial concentration in the regions of EU. Growth and Change, 37(2), 200–270.

Fagerberg, J. (2000). Technological progress, structural change and productivity growth: A comparative study. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 11, 393–411.

Fourastié, P. (1949). Le grand espoir du XXeme siecle. Progrés technique, progrés économique, progrès social. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Fuchs, V. (1968). The service economy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gemmell, N. (1982). Economic development and structural change: The role of the service sector. Journal of Development Studies, 19(1), 37–66.

Granger, C. W. (1969). Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica, 37, 424–438.

Gregory, M., Salverdad, W., & Schettkat, R. (2007). Services and employment explaining the US-European gap. New York: Princeton University Press.

Haaland, J., Kind, H., Midelfart-Knervik, K., & Tortensson, J. (1998). What determines the economic geography of Europe? Discussion Paper 19/98. Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration.

Hallet, M. (2000). Regional specialization and concentration in the EU (pp. 1–29). Economic Papers. European Commission 141.

Havlik, P. (2005, January 2005). Structural change, productivity and employment in the New EU Member States (WIIW Research Reports, 313).

Krüger, J. (2008). Productivity dynamics and structural change in the US manufacturing sector. Industrial and Corporate Change, 17(4), 875–902.

Maddison, A. (1996). Macroeconomic accounts for European countries. In B. van Ark & N. Crafts (Eds.), Qualitative aspects of post war European economic growth. Cambridge, MA: CEPT/Cambridge University Press.

Maroto, A. (2012). Productivity in the services sector. Conventional and current explanations. Service Industries Journal, 32(5), 719–746.

Maroto, A., & Cuadrado, J. R. (2007). Productivity and tertiarization in industrialized countries. A comparative analysis (Efficiency Working Series, 15-2007). University of Oviedo.

Maroto, A., & Cuadrado, J. R. (2009). Is growth of services an obstacle to productivity growth?’. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 20(4), 254–265.

Maroto, A., & Rubalcaba, L. (2008). Service productivity revisited. Service Industries Journal, 28(3), 337–353.

McLachlan, R., Clark, C., & Monday, I. (2002). Australia’s service sector: A study in diversity. Productivity Commission Staff Research Paper, AUSINFO: Canberra.

Midelfart-Knarvik, K. H., Overman, H. G., Redding, S. J., & Venables, A. J. (2003). Monetary union and the economic geography of Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies, 41(5), 847–868.

Molle, W. (1996). The regional economic structure of the European Union: an analysis of long term developments. In K. Peschel (Ed.), Regional growth and regional policy within the framework of European integration. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag.

Nusbaumer, J. (1987). The services economy: Lever to growth. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

O’Mahony, M., & van Ark, B. (2003). EU productivity & competitiveness an industry perspective. Can Europe resume the catching-up process? Brussels: EC Enterprise Publications.

OECD. (2009). How regions grow. Paris: OECD.

Peneder, M. (2002). Industrial structure and aggregate growth (WIFO Working Papers, 182). Wienn.

Peneder, M. (2003). Industrial structure and aggregate growth. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 14, 427–448.

Peneder, M., Kaniovski, S., & Dachs, B. (2003). What follows tertiarisation? Structural change and the role of knowledge -based services. Service Industries Journal, 23(2), 47–66.

Rubalcaba, L. (2007). Services in the European economy: Challenges and implications for economic policy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Salter, W. (1960). Productivity and technical change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schettkat, R., & Yocarini, L. (2006). The shift to service employment: A review of the literature. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 17, 127–147.

Stiroh, K. (2001). Information technology & the US productivity revival. What do the industry data say. New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Timmer, M., & Szirmai, A. (2000). Productivity growth in Asian manufacturing: The structural bonus hypothesis examined. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 11, 371–392.

Towse, R. (1997). Baumol’s cost disease: The arts and other victims. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Triplett, J., & Bosworth, K. (2004). Productivity in the US service sector. New sources of economic growth. Brookings Institution Press: Washington D.C.

Triplett, J., Bosworth, K., Triplett, J., & Bosworth, K. (2006). Baumol’s disease has been cured. IT and multifactor productivity in US service industries. In D. W. Jansen (Ed.), The new economy and beyond: Past, present and future. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

van Ark, B. (1995). Sectoral growth and structural change in post-war Europe (Research Memorandum GD-23). Groninge: GGDC.

van Ark, B., & Piatkowski, M. (2004). Productivity innovation and ICT in old and new Europe. GGDC Research Memorandum, 69. Groningen: Groningen Growth and Development Centre.

Young, A. (1995). The tyranny of numbers: Confronting the statistical realities of the East Asian growth experience. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 641–680.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Maroto-Sánchez, A., Cuadrado-Roura, J.R. (2013). Do Services Play a Role in Regional Productivity Growth Across Europe?. In: Cuadrado-Roura, J. (eds) Service Industries and Regions. Advances in Spatial Science. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-35801-2_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-35801-2_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-35800-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-35801-2

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)