Abstract

With their article on “Reputation in Relationships,” Money, Hillenbrand, and Downing respond to concerns with regard to existing measurement tools for corporate reputation. As topical issues concern stakeholder groups differently, and are likely to have varying levels of importance for different stakeholders, such insight gets lost in traditional rankings of reputation. The model introduced by Money, Hillenbrand, and Downing deals with these concerns and focuses on reputation in a particular stakeholder relationship. The application of structural equation modeling allows for prioritizing which aspects of reputation are likely to make the most impact on stakeholder behavior. With this approach, it is emphasized that reputation is not an end in itself. Rather, it aims at fostering favorable stakeholder behavior which can directly influence the financial performance of firms in terms of shareholder value. Therefore, the authors’ approach has the potential to be used as a tool by management to improve the performance of the firm.

This chapter is based on original research first published in the Corporate Reputation Review, by Keith MacMillan, Kevin Money, Steve Downing, and Carola Hillenbrand. Previously published material is reproduced by kind permission of the Palgrave Macmillan Ltd.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

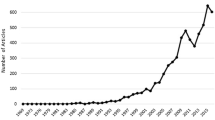

Even though reputation is an old idea, it is only within the last decade that it has been constructed as a management discipline and that corporate reputation is recognized as a key intangible asset of organizations (Money and Hillenbrand 2006; Fombrun and van Riel 2004; Roberts and Dowling 2002). Both practitioners and academics often describe reputation as a concept that is held in the minds of stakeholders and experienced in relational elements (Fombrun and van Riel 2004; Waddock 2002). While this is useful, recent reviewers of corporate reputation as a field of academic study have called for more theoretical development (Barnett et al. 2006; Wartick 2002) and more valid and practicable methods of assessment, comparison, and prediction (Bromley 2002; Wartick 2002).

In response to the need for more theoretical development, this chapter offers a definition and conceptualization of reputation that is based in direct exchange relationships. This is in line with the notion that a positive reputation in direct exchange relationships is key to business success (Freeman 2004; Waddock 2002). This extends the work of other reputation theorists who seek to conceptualize reputation as the perceptions of stakeholders towards a focal business organization (Davies et al. 2003; Fombrun 1996). Defining reputation in stakeholder relationships allows for the examination of how perceptions are rooted in relationships. It also enables to extend the analysis in two directions: first to show the causes of reputation derived from the experiences of relationships, and second to show the consequences of reputation in the form of in the intended future behaviors of stakeholders.

In response to the need for more valid and practicable methods of assessment, comparison, and prediction (Bromley 2002; Wartick 2002), this chapter offers a thorough examination and description of statistical properties, the research methodology utilized, the process of scale construction, and the modeling applied. In addition, the contribution addresses two further concerns with regard to existing measurement tools articulated by Bromley (2002): The first is Bromley’s skepticism of overall scores of reputation, such as the RQ and the Fortune measures, which are derived from applying exactly the same model of reputation across different stakeholder groups. Research has shown that stakeholder groups are likely to differ in their values and beliefs and are therefore likely to judge a company’s reputation in terms of different issues that are important to them (Fiedler and Kirchgeorg 2007). Bromley’s other criticism is of reputation scores or rankings that are derived from the sum or average of scores on a number of sub-scales. Different issues are said to have different levels of importance for different stakeholders, and it may be important for each issue to have passed a certain threshold for an organization to have a good reputation, regardless of how good other measures are.

The model in this contribution deals with both these concerns by focusing on reputation in a particular stakeholder relationship. It does not seek to aggregate the scores from one stakeholder relationship with that of other relationships. Nor does it sum or average a number of sub-scales in order to derive a reputation score for the relationships under investigation. The predictive power of the model derives from the overall pattern in a relationship and the application of structural equation modeling allows for prioritizing which aspects of reputation are likely to make the most impact on stakeholder behavior.

Theoretical Development

In a review of existing definitions, Barnett et al. (2006) find that definitions of corporate reputation fall into three classes: corporate reputation as an asset, as an assessment, and as awareness. Corporate reputation as an asset is often advocated by strategists seeking to explain firm performance (Money and Hillenbrand 2006). Corporate reputation as an assessment and awareness, on the other hand, places reputation in the perceptual context of organizational relationships (Money and Hillenbrand 2006). Most leading definitions of reputation to date have in fact regarded it as the total perceptions of all stakeholders towards a company. For example, Fombrün and Rindova (2000) describe corporate reputations as aggregate perceptions about the salient characteristic of firms. The authors continue by saying that this reflects a general esteem in which a firm is held by its multiple stakeholders. The over-riding objective in these studies appears to be to gain a total measure which can be related to the total intangible assets, brand equity or reputational capital of a business (Fombrun 1996).

However, capturing the perceptions of all stakeholders as a prerequisite to calculating a financial value for reputation is an enormous task. For a major company there will be millions of people who will have some sort of perception of it, gained in widely diverse ways. How can these millions of perceptions be captured and measured, let alone managed? Are all these perceptions equally important? And important to whom: managers, shareholders, government or regulators? These questions confront any researcher trying to make sense of the field of corporate reputation. In a recent review of the field, Lewellyn (2002) argued that future research needs to answer three very basic questions:

-

1.

Reputation for what?

-

2.

Reputation to whom?

-

3.

Reputation for what purpose?

These are therefore useful initial questions for this paper, as a means to categorize some of the main approaches and models in use and identifying significant gaps yet to be filled. By addressing these three questions, reputation will be operationalized in stakeholder relationships with a business.

Reputation for What?

Companies can have reputations for different characteristics, behaviors or outcomes. For example, one may be seen as having a reputation for being financially successful, another for being innovative, another for having high-quality goods or service. The oft-cited rankings in Fortune, Management Today, and the Financial Times emphasize criteria such as being well-known, respected, and having high levels of financial performance and innovation. Academic authors, such as Davies et al. (2003) see reputation in personality-like attributes, such as whether businesses are sincere, exciting or competent. Fombrun and Gardberg (2000) highlight characteristics such as emotional appeal, leadership, and financial performance, as well as the ability to meet stakeholders’ expectations. Gaines-Ross (1998) operationalizes reputation as exhibiting certain behaviors, such as being well-led or being effective communicators. Bromley (2002) argues that major companies “have as many reputations as there are distinct social groups (collectives) that take an interest in them” (p 36). These “collectives” are “relatively homogeneous groups of people with a degree of common interest in a reputational entity, such as a company” (p 36). In other words these “collectives” are essentially groups of stakeholders; so if reputations differ by stakeholder, this leads naturally to the next question – reputation as perceived by whom?

Reputation to Whom?

In principle, all people with perceptions of a business should be taken into account. But whose perceptions are the most critical? In practice authors focus most on one or two groups. Davies et al. (2003), for example, concentrates on the views of customers and employees; van Riel (1997) is primarily interested in employees, while Badenhausen (1998) focuses on the views of financial analysts but also adds senior executives from other companies. Analysts and senior executives are also most commonly used in the Fortune and Financial Times rankings. Implicit in these choices of stakeholder group must be assumptions of why their perspective is particularly important, and logically this must be related to the purpose of reputation. As Lewellyn (2002) says, “‘for what’ (and ‘for what purpose’) determines the reference group ‘to whom’.” (p 451).

Reputation for What Purpose?

In thinking through the purpose of reputation, one begins to identify whose views are most critical. Some writers assert that a good reputation (like a valued brand) commands premium pricing, or may involve lower marketing costs, attracts better employees, brings endorsements or acts as a buffer to criticism (Fombrun and Gardberg 2000; Fombrun et al. 2000). Davies et al. (2003) sees beneficial reputational outcomes in terms of customer loyalty and employee retention. Gaines-Ross (1998) affirms similar benefits. The underlying assumption is that these outcomes bring about better long-term financial performance and shareholder value, though the direct mechanism by which this is achieved may vary.

A closer analysis of the theories above suggests that the mechanism through which reputation impacts organizations is stakeholder relationships. Via, for example, the higher prices customers are prepared to pay for products with a good reputation or the increased productivity that may result from the higher level of commitments employees are suggested to demonstrate towards companies with a good reputation. Based on MacMillan et al. (2000), we argue that the stakeholders most able to influence these aspects of performance will be those that have direct monetary exchange relationships with the business, i.e., customers, employees, suppliers, investors, and government (representing the community). If the main benefits of a good reputation for a company are ultimately reflected in shareholder value, it is the exchange relationships that produce shareholder value that need to be studied. The argument can be illustrated by reference to the Stakeholder map in Fig. 1.

It is key premise of stakeholder theory that healthy stakeholder relationships underpin the long-term financial performance and social standing of a business (Freeman 2004; Sillanpää and Wheeler 1998). MacMillan and Downing (1999) highlight that the stakeholders in the shaded, inner box have cash exchanges with the business: money flows one way and something else such as goods, services, obligations or rights flow in the other direction. The groups in the outer box do not have direct significant cash exchanges with the business, but can influence the behavior of the direct exchange stakeholders towards the business. Furthermore, MacMillan and Downing (1999) argue that because shareholder value is based on future net cash flows, it follows that it is also largely based on the quality of direct exchange stakeholder relationships. Consequently it might be held that the everyday understanding of “goodwill” of stakeholders meaning a favorable disposition or feeling is closely linked to the accountants’ definition of goodwill, namely the surplus capitalization of the business above the value of the net assets. In other words, there is a relational basis to cash flow and capitalization values. In this article we develop this insight by showing that a reputation reflected in the perceptions of stakeholders is rooted in relationships and linked to the emotions and behaviors that generate cash flow. So to answer the question reputation for what purpose, generating goodwill in both relational and financial terms is key.

Bringing Together Reputation for What? to Whom? and for What Purpose?

Lewellyn (2002) requires reputation researchers to provide an integrated set of answers to the questions of reputation for what? for whom? and for what purpose? before they can develop measures of reputation, advance theory or be of practical value. In the sections above we have argued that generating goodwill is the key aim in developing and maintaining a reputation. This is the answer to the reputation for “what purpose” question. We have argued that this goodwill will be achieved by having supportive relationships with direct exchange stakeholders. This is the answer on the reputation “with whom” question. The reputation “for what” question can only be answered by reviewing what is important to each stakeholder group. Reputation measures should, therefore, include measuring perceptions of these important relationship issues. MacMillan et al. (2000) identified seven critical relationship categories which we believe are highly generalizable and were therefore used in the current study.

Conceptual Development: Operationalization of Business Relationships

Based on the empirical work of Morgan and Hunt (1994), MacMillan et al. (2000) propose a theoretical model to understand the development of goodwill in business relationships. MacMillan et al. (2000) present three sets of variables in their model: (1) a number of drivers of a business relationship which are the perceived behaviors, products, services, and values of a business, (2) the nature of the relationship itself which is characterized by what the stakeholder feels about the business, and (3) a number of outcomes of the relationship which are operationalized by stakeholders’ likely future behaviors towards the business. Stages (1) and (2) refer to stakeholder perceptions and represent the reputational component of the model. Stakeholder intentions represent the consequences of reputation. The operationalization in three stages allows the impact of reputation to be derived from the perceived behaviors of organizations on stakeholder behaviors to be measured. It also allows the consequences of reputation to be measured in terms of supportive and less-supportive stakeholder behaviors. The concepts in the MacMillan et al. (2000) model form the basis for the development of the survey instruments and are listed in Fig. 2.

Following MacMillan et al. (2000) this contribution defines and operationalizes reputation as “stakeholders, experience-based perceptions and feelings towards a business”. The outcome of reputation is defined in terms of stakeholder behavioral intentions towards a business.

Research Design and Questionnaire Development

For reason of access, customers of an insurance company were chosen as participants in this study. Elements of the model and generic survey instruments for each of these (the origins of which are outlined in Fig. 1) were contextualized in focus groups with both management of the organization and the customers.

The focus groups and interviews with the management were used to establish which intended stakeholder behaviors were judged to be critical for the future performance of the business and whether there were any particular elements not included in the theoretical model. The objective of the customer focus groups was to adapt the language in the questionnaire and make it relevant to customers in this sectoral context. In addition to this, these focus groups were important to ascertain which perceptions and experiences of the business were considered important in this context and whether any important elements were absent from the theoretical formulation.

The draft questionnaire was then piloted with a sample of customers to ensure each question was relevant and clearly worded. The results from the pilot tests were used to further refine the questionnaires and to design the final version. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statements in the questionnaire with reference to a 7-point Likert-type scale. Point 1 on this scale indicated strong disagreement, Point 7 strong agreement, and Point 4 neither agreement nor disagreement.

Data Collection

The final customer questionnaire was distributed to 10,000 customers of an insurance company and administered by post. About 2,825 customers responded, representing a response rate of 28%, which is acceptable for this type of research according to Baruch (1999). Whilst the full sample was used for application of an exploratory factor analysis, for methodological reasons a random sample of 600 customers out of the 2,825 responses was selected for application of structural equation modeling. The number of distinct parameters to be estimated in the final customer model was 134. A sample of 600 is in line with literature recommendations of a minimum sample size of at least five respondents for each estimated parameter while balancing this with requests to minimize the use of large samples in SEM (e.g., Hair et al. 1998).

Data Analysis

Data was captured in SPSS version 12.0 for Windows and subjected to a number of standard procedures to check for missing values and multivariate normality. The data was then analyzed in four separate but sequentially related steps:

-

1.

An exploratory factor analysis (Principal Component Analysis with Varimax Rotation) was conducted including all items of the questionnaire to explore the empirical data structure. The aim of the PCA was twofold: firstly to assess if the items group into a number of distinct and meaningful factors. Secondly to assess if the appropriate items loaded substantially on their hypothesized factors and no larger than 0.30 on any other factor. That was seen as necessary to differentiate the scales into aspects of reputation in relationships and consequences of reputation, analogous to the theoretical conceptualization.

-

2.

As a next step, items that loaded substantially (greater than 0.5, see Nunally 1978 for a discussion) on a common factor were exposed to reliability tests (Cronbach alphas). Relevant items that displayed sufficient reliability scores (of or above 0.7, see Forman et al. 1998) were combined to aggregated scales using the summated mean method.

-

3.

A correlation analysis was then conducted to understand the nature and direction of relationships between different scales, as well as the strength of association. Understanding the strength of these relationships was the basis for the application of structural equation modeling.

-

4.

In a final step, the data was analyzed with a Structural Equation Modeling technique (utilizing AMOS software version 5.0) to test the specification of the proposed model from MacMillan et al. (2000).

The results of all four steps of analysis are now reported.

Results

Step 1: Exploratory Factor Analysis

The results of the Principal Component Analysis suggested a 12-factor solution. This implies that it is possible to measure at least 12 distinct aspects of a relationship. The majority of items grouped together as expected from theory. The only difference was found in one factor that combined six items belonging to the constructs intrinsic benefit items and shared values. These six items were subsequently combined to one scale, which could be justified not only due to their empirical, but also to their theoretical closeness.

Step 2: Reliability Analysis

The results of the Reliability Analysis (Cronbach Alpha) showed that all but one scale exhibit satisfactory reliability indexes between 0.77 and 0.92 (Nunally 1978), see Fig. 3. The scale Termination Cost with a reliability index of 0.57 fell lower than desired. Based on theoretical consideration, termination cost was kept in the model, but treated with caution in further analysis (as will become apparent later, termination cost did not exhibit a significant link to either trust or commitment).

Step 3: Correlation Analysis

Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient was used as a measure for the linear associations between the constructs (Hair et al. 2003). The correlation coefficients range from 0.04 to 0.586. The results of the correlation analysis helped to reveal links that are likely to be strong in structural equation modeling and also help to identify if exogenous constructs are correlated, expressing a shared influence on endogenous variables (Hair et al. 1998).

Step 4: Structural Equation Modeling

The final model with standardized beta-weights and R-squared values is presented in Fig. 4. The rationale behind the specification of arrows is the link from reputation in relationship to consequences of reputation outlined in MacMillan et al. (2000). More specifically, the arrows go from customer perceptions and experiences of business behavior (left side) to customer feelings of trust and commitment towards a business (middle) to customer-intended behavior towards a business (right side).

All variables shown in Fig. 4 are latent constructs, measured with a number of items (between 2 and 10 each, see Fig. 3 for scale composition). The model is recursive. The exogenous constructs were allowed to correlate.

The model was tested using AMOS, estimating the significance of the paths (links) between the concepts as well as the predictive ability of the model. The results indicate support for almost all of the specified links. The Termination Costs – Commitment link was not significant, nor was the Past Trust-related Behaviors – Trust link or the Trust-Commitment link. (All other links in the model were significant to the 0.001 level).

The data fits the model well. The parsimony ratio is 0.918, the Tucker-Lewis Coefficient of 0.915 indicates a good fit, as does the Comparative Fit Index of 0.922. These are in line with guidelines given by Chin and Newstead (1999). [Note: The Goodness of Fit Index was 0.851 and the Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index was 0.831. These are both close to their recommended level of 0.9 given by Hair et al. (1998).]

Discussion of Results

The model displays considerable predictive power. More than three quarters of the variance of Trust was explained (R² of 0.84) through mainly Non-Material Benefits and Shared Values, but also through Material Benefits, Communication, and Coercive Power. Similarly, over half of the variance of customer Creative Collaboration (R² of 0.51) was explained. Interestingly, that was mainly achieved through Trust, while Commitment impacted slightly negatively on customers’ Creative Collaboration. The other endogenous variables also showed substantial R² values (Loyalty = 0.33; Compliance = 0.10; Future Trust-related Behavior = 0.77).

The results of the Structural Equation Modeling is now interpreted in combination with the mean scores of each construct reported earlier in Fig. 4 to give a fuller picture of the results. Scores above 4 on the 7-point scale may be interpreted as positive, whereas scores below 4 as negative perceptions of a business. The model and mean scores reveal a generally favorable picture of customer perception and feelings towards the business. There is a slightly above-average level of Trust which brings about positive supportive behaviors (mean score for trust: 4.49). Similarly, there is a relatively high level of Commitment which brings about positive supportive behaviors (mean score for emotions: 4.77).

However, the mean scores also reveal low levels of Creative Collaboration and intended Loyalty of customers towards the business. In order to improve the feelings of Trust which antecede Creative Collaboration and Loyalty, the model suggests that they should concentrate on increasing Non-Material Benefits and Shared values as well as Communication (as they are the main drivers of Trust and currently have relatively low mean scores). Other factors such as Material Benefits and Past Trust-related Behaviors are also important, but they have higher mean scores, suggesting that the greatest impact can be made by concentrating on Non-material Benefits, Shared Values, and Communication. (In this insurance context, Non-material Benefits include business’ behaviors such as contributions to the local community, ethical behavior, and observations about whether the firm treats its staff or other customers well. Communication involves informing customers as well as listening to their changing needs.) In order to improve Commitment which again antecedes Creative Collaboration and Loyalty, the model suggests that improving Communication and considering the impact of Termination Costs is key. Again, it is important to keep delivering relatively high levels of Material Benefits and Past Trust-related Behaviors and if possible even improving them.

Practical Implications

What practical utility does this approach have for management? The first benefit is that it gives organizations an indication of how they are perceived by their key stakeholders and how these stakeholders are likely to behave towards them in the future. It improves the self-awareness of the business and also indicates whether stakeholders view the business in a positive or negative light.

Managers can obtain information about mean scores for each construct, or they may use information about the frequency of stakeholder perceptions about each construct. To illustrate this point further, customers perceive material benefits provided by the organization as rather positive, with a mean score of 4.91. In frequency terms, the results show that over two-thirds of customers (69%) rate material benefits above average (scores between 5 and 7 on a 7-point scale), less than one-fifth of customers (17%) rate them as average (score of 4), and only 14% if customers rate them below average (scores between 1 and 3).

A further benefit for managers is that the model displays the pattern of perception across constructs by linking stakeholder perceptions and experiences to their future intended behaviors. Managers can identify via the model the perceptual or experiential antecedents of an intended behavior and then take appropriate actions to improve it. This provides much richer information to management than simply one overall score for reputation.

Implications for Reputation Measurement

The conceptualization of reputation offered in this paper is specific to particular stakeholder groups rather than constituting a single overall measure of reputation derived from all stakeholder groups or the general public. This is based on the assumption that people’s perceptions about an organization will depend on which stakeholder group they belong to and what sort of relationship they have with an organization. It is also based on the belief that stakeholders gain their perceptions primarily through their direct experiences rather than what they learn in the media and from other people. The better these experiences, the more likely it is that the stakeholders will trust the organization and have positive emotions towards it. The stronger these feelings, the more likely it is that stakeholders will behave in supportive ways towards the organization in the future. In our formulation the experience and feelings towards a business constitutes its reputation, while the intended behaviors constitute the consequences of reputation.

The results make a number of contributions:

-

1.

The theoretical distinction between experiences, emotions, and intentions claimed by MacMillan et al. (2000) is empirically justified. In addition to this, individual elements of experiences, emotions, and intentions in this model were found to be distinct. This is demonstrated by the factor analysis results.

-

2.

These distinct elements can be measured reliably. This is demonstrated by the Cronbach Alpha reliability tests. On a practical level, businesses can thus understand if they have good or bad reputations for each of the distinct aspects in the model, by looking at the mean scores.

-

3.

These elements can also be linked causally and this causal model provides a parsimonious solution for the data. This is shown by the SEM results. On a practical level this means that a business can identify which elements of stakeholder experience are most critical in predicting the future behavior of stakeholders towards the business (e.g., whether stakeholders will be supportive or unsupportive towards the business in the future).

Conclusions and Limitations

The study of corporate reputation is still at a formative stage. This paper has been a response to calls for more theoretical and methodological development that can be readily applied by management (e.g., Bromley 2002; Wartick 2002).

The proposed formulation of reputation and its consequences in stakeholder relationships complements other, overall measures of reputation that are used to provide relative rankings and league tables. Our approach, however, does not assume that reputation is an end in itself. Rather, it focuses on stakeholder-intended behaviors, which it has been argued, should directly influence the financial performance of firms in terms of shareholder value. The approach therefore, has the potential to be used as a tool by management to improve the performance of the firm. Whether this aspiration will ever be realized will depend on further critical review, extensions of the model and applications to other contexts, as the research reported in this contribution is based on data from one organization and one stakeholder group, customers, in a cross-sectional study design. While this does provide some evidence of the validity of the model, there is a clear need to apply this approach to a number of other organizational and stakeholder contexts and in a longitudinal way before firmer conclusions about generalizability can be made.

References

Badenhausen K (1998) Quantifying brand values. Corp Reput Rev 1(1/2):48–51

Barnett ML, Jermier JM, Laffert BA (2006) Corporate reputation: the definitional landscape. Corp Reput Rev 9(1):26–38

Baruch Y (1999) Response rate in academic studies – a comparative analysis. Hum Relat 52(4):421–439

Bromley D (2002) Comparing corporate reputations: league tables, quotients, benchmarks, or case studies? Corp Reput Rev 5(1):35–51

Chin WW, Newstead PR (1999) Statistical strategies for small sample research. In: Hoyle RH (ed) Structural equation modelling. Sage, London

Davies G, Chun R, DaSilva RV, Roper S (2003) Corporate reputation and competitiveness. Routledge, London

Fiedler L, Kirchgeorg M (2007) The role concept in corporate branding and stakeholder management reconsidered: are stakeholder groups really different? Corp Reput Rev 10(3):177–188

Fombrun CJ (1996) Reputation. Realizing value from corporate image. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

Fombrun C, Gardberg N (2000) Who’s top in corporate reputation. Corp Reput Rev 3(1):13–17

Fombrun CJ, Rindova VP (2000) The road to transparency: reputation management at Royal Dutch/Shell. In: Schultz M, Hatch MJ, Larsen MH (eds) The expressive organization. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fombrun CJ, van Riel C (2004) Fame and fortune: how successful companies build winning reputations. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Fombrun C, Gardberg N, Sever JM (2000) The reputation quotient: a multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. J Brand Manag 7(4):241–255

Forman S, Money A, Page MJ (1998) How reliable is reliable? A note on the estimation of Cronbach alpha. In: Proceedings of the international management conference, Cape Town, South Africa, pp 1–26

Freeman E (2004) Stakeholder theory and corporate responsibility: some practical questions. Key note presentation on the 3rd Annual Colloquium European Academy of Business in Society, Gent, Sept 2004

Gaines-Ross L (1998) Leveraging corporate equity. Corp Reput Rev 1(1/2):51–56

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (1998) Multivariate data analysis, 5th edn. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Hair JF, Babin B, Money AH, Samouel P (2003) Essentials of business research methods. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Lewellyn PG (2002) Corporate reputation. Focusing the zeitgeist. Bus Soc 41(4):446–455

MacMillan K, Downing SJ (1999) Governance and performance: Goodwill hunting. J Gen Manag 24(3):11–21

MacMillan K, Money K, Downing SJ (2000) Successful business relationships. J Gen Manag 26(1):69–83, Autumn

Money K, Hillenbrand C (2006) Using reputation measurement to create value: an analysis and integration of existing measures. J Gen Manag 32(1):1–12

Morgan RM, Hunt SD (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J Market 58:20–38

Nunally JC (1978) Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hall, New York, NY

Roberts PW, Dowling GR (2002) Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strat Manag J 23:1077–1094

Sillanpää M, Wheeler D (1998) The stakeholder corporation. Financial Times Prentice Hall Publishing, London

Van Riel CBM (1997) Research in corporate communication. Manag Commun Q 11(2):288–310

Waddock S (2002) Leading corporate citizens. Vision, values, value added. McGraw-Hill, Irwin, NY

Wartick SL (2002) Measuring corporate reputation. Bus Soc 41(4):371–392

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Money, K., Hillenbrand, C., Downing, S. (2011). Reputation in Relationships. In: Helm, S., Liehr-Gobbers, K., Storck, C. (eds) Reputation Management. Management for Professionals. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-19266-1_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-19266-1_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-19265-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-19266-1

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)