Abstract

The concept of corporate reputation is steadily growing in interest among management researchers and practitioners. In this article, we trace key milestones in the development of reputation literature over the past six decades to suggest important research gaps as well as to provide contextual background for a subsequent integration of approaches and future outlook. In particular, we explore the need for better categorised outcomes; a wider range of causes; and a deeper understanding of contingencies and moderators to advance the field beyond its current state while also taking account of developments in the macro business environment. The article concludes by presenting a novel reputation framework that integrates insights from reputation theory and studies, outlines gaps in knowledge and offers directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

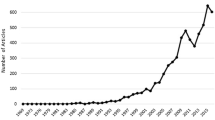

Corporate reputation (CR) and its related terms and concepts are receiving considerable attention in management theory and practice, as evidenced in 20 years of Corporate Reputation Review articles and celebrated in this anniversary issue. Despite growing interest, however, CR research is often criticised as being ambiguous, loosely scattered across various disciplines and difficult to conduct due to the intangible nature of the concept (Herbig and Milewicz 1993; Lewellyn 2002; Deephouse and Carter 2005; Barnett et al. 2006; Brown et al. 2006). As CR is nevertheless widely seen to hold much promise for the future of management theory and practice, we dedicate this article to a review and integration of CR studies with the hope that our work may contribute towards more clarity in the field and appealing avenues for future research. As such, this article aims to make three key contributions.

First, a review of the existing reputation literature is provided in Sect. 2 of this article with the aim of summarising key milestones over the past six decades. The review describes key streams of CR research and important research gaps while also indicating common themes and merging viewpoints across time periods and from different perspectives. Hence, Sect. 2 is organised in three subsections, summarising CR literature in the time periods from 1940 to 1990, 1990 to 2006 and 2006 to 2017 (present). These periods are chosen as they offer a useful way to highlight important conceptual developments over time and offer interesting insights regarding the growth of the field. Any division of an academic field in separate time periods is imposed and there will naturally be overlap and crossover between time periods, publication dates and conceptual developments. The chosen time periods in this article should thus be seen as an attempt to introduce a structure that is useful for the purpose of this review, rather than proposed to be definite by nature.

Insights into how CR research evolves over these periods extend previous reviews by scholars such as Walker (2010), who reviews definitions of CR and Lange et al. (2011), who focuses on one decade from 2000 to 2010 primarily with regard to exploring reputation as a concept related to familiarity, favourability and beliefs about future expectations of organisations. By reviewing reputation research across 6 decades up until 2017, this paper explores a wider range of issues including whether a commonly chosen level of analysis in CR studies is the organisation or the individual; whether CR is conceptualised from a strategic or relational perspective; how CR is thought to be best measured; if and how the idea of stakeholders is integrated in CR studies; and how CR research is linked to other academic areas, disciplines and management theories. Interestingly, the review indicates that research is progressing from a focus on measuring CR as a ‘standalone’ concept (and if linked to other areas then mostly to the financial performance of organisations) to research aiming to embed CR into a more comprehensive analysis of causes and outcomes as a way to understand the development and wider purpose of CR, i.e. its antecedents and consequences. While the Lange et al. (2011) review proposes a deeper exploration of the causes of reputation, this article also differs from previous work as it outlines that much is still unknown with regard to the underlying mechanisms by which CR develops in different circumstances, such as the contingencies and moderators at play, how the concept links to key developments and insights in related disciplines and how changes in the business environment can best be embedded in future research.

As a second contribution of this article, therefore, Sect. 3 discusses key gaps in current knowledge and suggests opportunities for future research as relating particularly to the need for better categorised outcomes, a wider range of causes and a deeper understanding of contingencies and moderators. Importantly, Sect. 3 takes account of developments in both business and society, and links the need for future CR research to macro trends such as disparity of power between governments and business; population growth, urbanisation and climate change; and instantaneous connectivity and global information flow.

Building on the contextual background provided in Sect. 2, and building on the discussion of research gaps and current business trends in Sect. 3, the article finishes by offering an integration of CR themes and approaches in Sect. 4 by presenting a novel reputation framework and suggestions for future development of the field. The framework distinguishes between organisation-oriented and stakeholder-oriented levels of analysis and organises causes and outcomes of CR in a sequential manner with suggested themes, moderators and feedback loops as the third and final contribution of this article.

Review of Reputation Literature

The evolution of CR literature is displayed chronologically in Table 1, as a way of demonstrating the development of thinking over critical time periods.

The time periods 1940–1990, 1990–2006 and 2006–2017 are chosen in this article to represent important conceptual developments: from 1940 to 1990 CR is predominantly looked at in terms of assets and signalling power and is often conceptualised from a strategic perspective. This early stage of CR research is, in hindsight, sometimes referred to as unidirectional in that CR is seen to be managed ‘from company to stakeholder’ (Balmer 1998) and, unsurprisingly, the level of analysis is often the organisation. From 1990 to 2006, a strategic/asset-based perspective on CR as well as a relational perspective gain momentum. The concept of stakeholders gets more integrated into CR literature, as scholars call for studies including the perspective of recipients/observers of CR, and as a consequence more studies from an individual level of analysis emerge. Importantly, a number of scholars propose ways of measuring CR in this time period and attempts are made to place CR into causal frameworks. From 2006 onwards, both a strategic and relational approach to CR research continue to coexist and scholars in both camps call to increasingly study antecedents and consequences of CR as a way to determine causes and outcomes. Also, links are increasingly being made between CR and other academic theories and disciplines as scholars are looking for complexity as well as nuance and subtlety; and for integration of findings and knowledge. Recent literature also points to the need to better understand contingencies and underlying mechanisms of the development of CR and to link CR research more systematically to wider trends in the macro environment.

Time Period 1940–1990

Corporate reputation as an academic subject is suggested to originate from the public relations literature in the United States in the late 1940s (Barlow and Payne 1949; Woodward and Roper 1951; Christian 1959; Macleod 1967; Weaver 1988), when large US corporations were seen to express an interest in the views of local communities. Interestingly, in this period, MacLeod (1967) poses three critical questions that could be seen to describe the heart of much subsequent reputation research and are still relevant today: ‘What is a company’s reputation based on? How is it measured? How can a company use its reputation to specific advantage?’ (p. 67).

Typically, at this early stage, CR is described as a strategic intangible asset that can contribute to current and future profitability and competitive advantage (Shrum and Wuthnow 1988; Weigelt and Camerer 1988; Cloninger 1995). The mechanisms for success are often explained through the signals that CR sends about a company’s attractiveness and capability (Milgrom and Roberts 1986; Riahi-Belkaoui and Pavlik 1991; Bagwell 1992). Later, often reviewed with reference to signal theory (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Turban and Greening 1997; Basdeo et al. 2006), studies in these years therefore often focus on how, when and why good reputations may signal desired corporate benefits, e.g. competitive advantage, better applicants and financial performance (Shapiro 1982, 1983; Freeman 1984; Weigelt and Camerer 1988; Dutton and Dukerich 1991).

Given the early reliance of CR studies on strategic thinking and links to profitability, the conceptual developments by Shapiro (1983), Weigelt and Camerer (1988) and Fombrun and Shanley (1990) mark significant milestones in CR literature. Shapiro (1983) is among the first to offer theoretical and empirical evidence on the impact of CR on financial return and this work significantly influences later studies on the link between CR and financial performance (e.g. Cloninger 1995; Hammond and Slocum 1996; Roberts and Dowling 1997; Miles and Covin 2000; Kitchen and Laurence 2003; Sabate and Puente 2003; Carmeli and Tishler 2004a, b; Neville et al. 2005). Weigelt and Camerer (1988) enrich the debate through a focus on a set of corporate attributes that the authors suggest to contribute towards CR development. Moving the field forward, Fombrun and Shanley (1990) then suggest a yet broader set of elements (from financial to emotional) relevant to CR. In doing so, the authors start to mark a transition in CR literature from a mainly strategic lens towards a relational and perception-based approach in the next time period, as they start to signal the perspective of external constituents as well as cognitive and emotive elements in the conceptualisation of CR.

Time Period 1990–2006

From the 1990s onwards, CR research spreads noticeably from the United States to Europe with more studies emerging, for example, from scholars in the UK (e.g. Bromley 1993; Balmer 1998; Macmillan et al. 2000, 2004), Germany (e.g. Wiedmann 2002; Walsh and Wiedmann 2004; Wiedmann and Buxel 2005), Italy (e.g. Zattoni and Ravasi 2000; Ravasi 2002; Gabbioneta et al. 2007) and the Netherlands (e.g. van Riel 2002; Berens and van Riel 2004; Maathuis et al. 2004).

While the earlier discussed stream of strategic CR research continues to thrive (Hall 1992; Grunig 1993; Yoon et al. 1993; Dollinger et al. 1997; Roberts and Dowling 1997, 2002; Carmeli and Tishler 2004a, b), often now theorised on the resource-based view of the firm (Barney 1991; Hall 1992, 1993; Deephouse 2000), an alternative perspective is starting to emerge in the literature that views CR as perception based (Wartick 1992; Bromley 1993; Fombrun 1996; Chun 2001; Mahon and Wartick 2003; Dowling 2004; MacMillan et al. 2004). At the time of the millennium, two distinct streams of CR research are clearly present: reputation as intangible asset, with research often conducted at the organisational level, (e.g. Roberts and Dowling 1997, 2002; Petrick et al. 1999; Deephouse 2000; Waddock 2000) and reputation as stakeholder perceptions, with research often conducted at the individual level (e.g. Balmer 1998; Bromley 2001; Johnston 2002; Mahon and Wartick 2003; Macmillan et al. 2004; Walsh and Wiedmann 2004).

A contribution to define CR from a perceptual perspective is then provided by Wartick (1992) arguing that ‘corporate reputation is the aggregation of a single stakeholder’s perceptions of how well organisational responses are meeting the demands and expectations of many organisational stakeholders’ (p. 34). A related definition is offered by Fombrun (1996), who sees reputation as ‘a perceptual representation of a company’s past actions and future prospects that describes the firm’s overall appeal to all of its key constituents when compared with other leading rivals’ (p. 72), which remains one of the most cited definitions in the literature (Dowling 2016).

Indeed, defining and differentiating CR is what many writers in the time period 1990–2006 aim to achieve. While early scholars hardly differentiate between the concepts of image, identity and reputation, and often use these terms interchangeably (Christian 1959; MacLeod 1967; Dunne 1974), scholars in the 90 s and early 2000s try to be more explicit (see for example Ettorre 1996; Fombrun and van Riel 1997; Nowak and Washburn 2000; Davies et al. 2001; Pruzan 2001). In an attempt to simplify the field, Brown et al. (2006)—in a seminal work and similar to Cornelissen et al. (2007)—refer to identity as internal associations about a company, which are held by its members (based on Albert and Whetten 1985); to organisational image as internally held associations, which reflect how others view a company; and to CR as external individual stakeholders’ views of the organisation.

Furthermore, measuring CR emerges as a key ambition of scholars in the time period 1990–2006. Measurement tools and framework are published, for example, by scholars such as Fombrun (1996), Davies et al. (2003), Berens and Van Riel (2004) and MacMillan et al. (2004). In an effort to categorise and summarise measurement tools, Money and Hillenbrand (2006) propose a reputation framework that integrates existing measurement models and differentiates between scales relating to causes, reputation and consequences of CR. Their framework builds on the seminal work by Rindova et al. (2005) and Walsh and Wiedmann (2004) to integrate organisational and stakeholder-oriented approaches to CR with the use of well-established psychological theory, and is displayed in Fig. 1.

As evident in the development of CR measurement tools and CR definitions between 1990 and 2006, CR literature becomes increasingly intertwined with stakeholder research (e.g. Morgan and Hunt 1994; O’Hair et al. 1995; Huang 1998; Broom et al. 2000; Macmillan et al. 2000; Yang and Grunig 2005). As such, CR scholars are often using exchange theory (Anderson and Weitz 1992; Lambe et al. 2001) and relationship reciprocity (Gassenheimer et al. 1998; Wulf et al. 2001; Greenwood 2007) as theoretical underpinnings of conceptual developments, and pay increasing attention to a two-way nature of company–stakeholder relationships, which correspond with Freeman’s (1984) original work on stakeholder theory, where he defines stakeholders as ‘anyone who affects and is affected’ by a company.

The shift to stakeholders and stakeholder perception in CR studies is furthermore accompanied by a shift to more research looking at the emotional, cognitive and behavioural elements of CR (Dutton and Dukerich 1991; Bromley 1993; Dutton et al. 1994; Balmer 1998; Chun 2005; Walsh et al. 2009a, b). Corporate reputation studies thereby include both research with internal stakeholders (Dutton et al. 1994; Gioia and Thomas 1996; Post and Griffin 1997; Arnold et al. 2003) and external stakeholders (e.g. Goldberg and Hartwick 1990; Bromley 1993; Dowling 1993; Vendelø 1998; Davies et al. 2001). Scholars such as Bromley (1993) also increasingly call for research to include the outcome behaviours of stakeholders—a notion that will emerges further in the next and final time period discussed in this article.

Time Period 2006–2017 (Present)

With the strategic/asset-based as well as the relational/perception-based approach to CR both well established by 2006, recent work often aims to better ground, legitimise and understand CR by linking it explicitly to management theories and other disciplines.

From a strategic/asset-based perspective, work is conducted, for example, by Srivoravilai et al. (2011) utilising institutional theory (see also Rao 1994; Staw and Epstein 2000; Deephouse and Carter 2005; Foreman et al. 2013; Davies and Olmedo-Cifuentes 2016; Deephouse et al. 2016); by Gardberg et al. (2015) utilising signalling theory (see also Basdeo et al. 2006; Newburry 2010; Walsh et al. 2016b, 2017; Gardberg et al. 2017); by Mahon et al. (2004) building on non-market strategy (see also Mahon and Wartick 2003; Ghobadian et al. 2015; Liedong et al. 2015) and by Deephouse (2000) and others utilising resource-based theory (see also Roberts and Dowling 2002; Shamsie 2003; Carmeli and Tishler 2004a, b; Carter and Ruefli 2006; Bergh et al. 2010). Furthermore, Carroll and McCombs (2003) bring agenda-setting theory to CR literature, and explore effects of media on CR development (see also Kiousis et al. 2007; Carroll 2010, 2013; Besiou et al. 2013; Bantimaroudis and Zyglidopoulos 2014; Lee et al. 2015).

From a relational/perception-based perspective, Wang and Berens (2015) use stakeholder theory (see also Cable and Graham 2000; Kreiner and Ashforth 2004; Parent and Deephouse 2007; Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Freeman 2010); and Money et al. (2012a, b) build on psychological approaches and relationship theories (see also MacMillan et al. 2004, 2005; Hosmer and Kiewitz 2005; Rindova et al. 2005; Korschun et al. 2014; Walsh et al. 2017). Korschun (2015) draws on social identity theory and explores psychological contributors to stakeholder relationships (see also Helm 2011a, b, 2013; Ashforth et al. 2013; Korschun and Du 2013; Beatty et al. 2015); Sjovall and Talk (2004) utilise attribution theory to understand how cognitive processes drive stakeholders to form perceptions of CR (see also Love and Kraatz 2009, 2017; Mishina et al. 2012; Helm 2013); and Ravasi (2016) utilises identity and identification theories (see also Whetten et al. 2014; Ravasi and Canato 2013).

While scholars across CR camps (and utilising a variety of theoretical underpinnings) call for more nuanced CR research and better developed models, the authors of this article are particularly affiliated with the relational/perception-based view of CR, and will thus focus on research gaps and future outlook particularly from that perspective in the rest of this article. While the authors warmly welcome a broadening of CR study beyond the relational view, a review and outlook analysis in that regard is better served by scholars who actively publish in this area.

Within the relational approach to CR research, much research from 2006 onwards focuses on a deep exploration of stakeholder perceptions, emotions, beliefs and thoughts (Money and Hillenbrand 2006; Helm 2011a, b; Ponzi et al. 2011; Fombrun 2012; Helm 2013), often with the hope to shed light on a longstanding and worrying lacuna in CR research: why stakeholders often react unpredictably and differently to the same organisational stimuli (Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Walker 2010; Mishina et al. 2012; Money et al. 2012a, b; West et al. 2015). Hence, one important stream of CR research from 2006 onwards addresses the underlying processes that underpin relationships and attitude development of individuals. However, while scholars are often interested in unpacking underlying (often psychological) mechanisms by which CR leads to stakeholder behaviour (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Walker 2010), the range of outcome behaviours explored in CR literature still remains limited.

Corporate reputation-related outcomes and benefits that are typically studied include, for example, stakeholder loyalty and commitment (Helm 2007; Caruana and Ewing 2010; Eberl 2010; Bartikowski et al. 2011); purchase intentions among customers (e.g. Sen and Bhattacharya 2001; Walsh et al. 2006, 2009a, b; Carroll 2009; Hong and Yang 2009); intentions to invest or seek employment (e.g. Einwiller et al. 2010; Newburry 2010; Ponzi et al. 2011); and advocacy or word of mouth (e.g. Hong and Yang 2009; Eberle et al. 2013; Cai et al. 2014; Chang et al. 2015).

These stakeholder behaviours seem mostly focused on commercial benefit for companies, and questions are arising about a potentially wider range of outcomes related to CR that could be of interest to study. Money et al. (2009), Shamma and Hassan (2009), Newburry (2010), Ponzi et al. (2011) and Garnelo-Gomez et al. (2015), for example, call for research that links reputation to outcomes such as, sustainable consumption, employee wellbeing, and pride and happiness of communities. This will be discussed more fully in Sect. 3.

Related to the previous point, CR scholars also call for studies to better understand the causes of stakeholder perceptions and feelings (Ponzi et al. 2011; Fombrun 2012). Fombrun (2012), for example, suggests three sources for reputation drivers as stakeholders’ personal experiences, corporate initiatives and other communication/media. As such, CR scholars are advised to not operate in isolation but, rather, build on advances in the study of perceptions and emotions more widely. For example, a recent study exploring sustainable living (Money et al. 2016) utilises advances in the understanding of human motivation and, in particular, the work of Lawrence (2010) and Lawrence and Nohria (2002) as the lens through which the developments of perceptions and emotions related to sustainable behaviours are developed.

Again, this point will be further explored in Sect. 3, as the authors believe that understanding the causes of CR holds much promise: often, the starting point of such attempts is a deeper understanding of human nature, which does not presume humans are rational or logical in decision making, as many early management studies in this domain do. Rather, seemingly irrational behaviours such as unsustainable consumption patterns can be explained in terms of the broader impact of an imbalance in expression of human drives in Western society.

Finally, there is a strong call in recent CR studies to better understand the contingencies and moderators at play in CR research. Much recent work still looks at stakeholders as homogeneous groups, often assuming that stakeholders within functional silos (e.g. customers, employees, communities) respond and act towards a company in a unified manner, without being able to systematically account for differences in responses of individuals (Walsh and Beatty 2007; Hong and Yang 2009; Chun and Davies 2010; Johnston and Everett 2012; Helm and Tolsdorf 2013). However, new studies are emerging that aim to explain varied responses within stakeholder groups (Mishina et al. 2012). These studies are based, for example, on identity and identification theories (Mael and Ashforth 1992; Ahearne et al. 2005; Bhattacharya et al. 2009; Remke 2013) or on the study of psychological concepts such as social axioms (i.e. deeply held beliefs about the world in general, such as cynicism and fate control) (West et al. 2015).

In summary, important research gaps in contemporary CR studies often relate to a need to better categorise CR outcomes, more fully understand the drivers of CR and to explore in depth the contingencies and moderators at play in how CR-related perceptions, emotions, beliefs and behaviour develop in individuals, above and beyond traditional stakeholder groupings. At the same time, there is a need to research CR within the contemporary business environment (see Ghobadian et al. 2015). Section 3 of this article will therefore explore these research gaps in light of macro business trends and Sect. 4 will propose a novel conceptual framework to outline interesting areas for future research.

Integration of Contemporary CR Research with Macro Business Trends

The research gaps identified in Sect. 2 mirror developments in wider business and society research and practice as scholars and practitioners alike suggest that the study of CR needs to change because the world and what we know about the world is changing (Money et al. 2016). In an attempt to integrate the academic need for CR advancement with developments of a rapidly changing business environment, this section explores macro business trends in light of CR theory and research. According to Ghobadian et al. (2015), the following macro trends in the business environment will have a great impact on company–stakeholder relationships in the coming decades:

-

disparity of power between governments and business

-

population growth, urbanisation and climate change

-

electronic information and instantaneous connectivity between people.

The authors fully acknowledge that there are many other developmental issues that are important but not included in the above, but hope that by exploring the ones listed here, this article provides a starting point for other scholars to add to.

The Need for Better Categorised Outcomes of CR—Speaks to Increasing Disparities in Business Realities and the Question of Organisational Purpose

An increasing disparity between governments and large businesses, in which governments encounter constraints while businesses become increasingly powerful, suggests that organisations could more deeply consider their purpose and the outcomes they seek—and as such better categorise the consequences of CR. The authors invite researchers and practitioners to consider and develop key performance indicators as outcomes of CR that can more accurately reflect the stated purposes of organisations.

With many governments facing years of austerity following the recession in 2008 and the seemingly increasing divisions between nations, multinational corporations (through their wide reach and supply chains) are seen by many to be in a better position to address global issues, such as food and water security, social justice and equality, and the preservation of natural resources (Scherer and Palazzo 2011; Austin and Seitanidi 2012; Brammer et al. 2012). From a CR perspective, this poses interesting questions for organisations and their leadership: e.g., how far do organisations want to take on wider responsibilities, such as encouraging sustainable consumption or reducing obesity?

This emphasises the need for organisations to reflect and communicate issues relating to ‘what are we trying to cause?’ through their actions, and to choose key performance indicators (KPIs) that fit with their purpose (Holt and Littlewood 2015). A global business like Unilever, for example, is setting targets that relate not only to purchase figures, but to social benefit, thereby inspiring people to use products that are more sustainable. Without appropriate KPIs—which we label as consequences of reputation—organisations will not have the means to manage progress towards their goals. While the authors do not advocate a particular purpose for any organisation, it is interesting to reflect that recent research suggests, for example, that ‘not acting’, or ‘not explaining inaction’ on issues related to sustainability and fair work practices can have a negative impact on reputation (Korschun 2015).

A systematic categorisation of meaningful outcomes of CR allows organisations and their leaders to carefully think through strategies and potential impacts with an end in mind, and will be integrated into the framework in Sect. 4 of this article in the following manner: following Money et al. (2012b), outcomes of CR will be categorised in terms of a hierarchy that starts with affective outcomes (such as trust and positive emotions); moves to maintaining behaviours (such as staying in a relationship); and then moves to expanding behaviours that require discretionary effort (such as advocacy). This categorisation builds upon insights from psychology literature, which suggest that behaviour change is often slow and builds in increments from the current expression of behaviour (e.g. Unsworth et al. 2013; Davis et al. 2015). For example, if a person has low levels of affect and trust towards an organisation, it is often more difficult to influence positive advocacy than if someone started with a higher level of trust. A feature of current CR research is that it often seeks to understand desirable behaviours such as advocacy rather than exploring existing behaviours or attitudes in more depth and seeking incremental change. The authors propose a categorisation of behavioural outcomes as follows:

-

1.

Maintain—continue with an existing behaviour—this could relate to behaviours that are directly beneficial to organisations, such as stakeholder retention and compliance, but could also include a broader set of behaviours, such as volunteering, or desirable end-states, such as wellbeing, engagement or life satisfaction.

-

2.

Stop—this involves stakeholders changing their behaviour and no longer engaging in certain activities. In many ways, this is the most difficult outcome to influence because it involves changing of habits. This could involve behaviours directly linked to organisations, such as cessation of unsafe working practices, or those linked to broader societal outcomes, such as reducing overconsumption or substance misuse.

-

3.

Start—this involves stakeholders either engaging in a new relationship (e.g. becoming an employee, customer etc.) or new action (e.g. starting to recycle, volunteer etc.), but may also involve stakeholders engaging more deeply with organisations (e.g. cooperating with organisations, providing more information, recommending initiatives on social media platforms) or changing the way that stakeholders engage in existing behaviours (e.g. this may include using products in more sustainable ways, such as washing clothes at a lower temperature, driving more economically, volunteering more often within a community).

The starting point of the above-suggested categorisation is the current behaviours of stakeholders—which are often seen as a useful lever to influence behaviour. For example, it may take different experiences to encourage someone to continue as opposed to start volunteering. Conceptually, ways of achieving such behavioural outcomes of maintain, stop and start are offered in exchange theory and reciprocity theory in stakeholder–organisation relationships. More specifically, this may include ‘the firm offering something of value to stakeholders’ before ‘stakeholders offer something of value back to the organisation or society’, in terms of specific maintain, stop or start behaviours (Money et al. 2012b: p. 8). Bhattacharya et al. (2009) suggest that these ‘offerings’ might have a tangible or intangible nature.

Outcomes are deliberately placed at the end of the framework in Sect. 4. It is at this end that the authors would invite both scholars and practitioners to start their journey by asking questions such as ‘What is the outcome we are seeking to understand or influence?’ and ‘What is the current state within the stakeholder universe?’. By doing so, the authors believe that CR research can become truly strategic and be a force for organisations achieving outcomes including but beyond financial returns.

The Need for a Wider Range of Causes of CR—Speaks to Changing Norms, Perceptions and Knowledge of Issues Such As Climate Change, Urbanisation, Population Growth and Increased Electronic Connectivity Between Individuals, As Well As Advances in the Study of the Psychology of Perception

Issues such as climate change, urbanisation and population growth are no longer contested by mainstream academics, politicians and practitioners. This means that the causes of CR will increasingly depend on meeting expectations in relation to these issues, as CRs and organisational activities will be judged by stakeholders in light of these realities. At the same time, advances in the study of human perception provide a richer tapestry of theory through which causes of reputation can be understood.

The causes of CR are levers that reflect both underlying human psychology and changing societal expectations. Such changing expectations may, for example, result in a changing psychological contract between business and society in which organisations can reflect more openly on their purpose and consider how purpose can be co-created with stakeholders and can take account of the concerns of broader societal stakeholders (Ansari et al. 2012; Leach et al. 2012; Arend 2013; Littlewood 2014). The authors propose that within a perception-based approach to CR, the causes of CR reside in stakeholder experiences. Critically, however, the authors propose that it will be useful to distinguish between the way experiences are categorised and also invite a wider set of causes to take advantage of both a better understanding of the psychology of experience as well as the changing nature of stakeholder expectations:

-

1.

Functional drivers of CR. These drivers are perhaps the most widely researched and used causes and have their origins in well-known measurement tools such as the Reputation Quotient (Fombrun et al. 2000), RepTrak® (Fombrun et al. 2015) and Most Admired Company Indicators. Categorisation of stakeholder experiences in terms of functions within an organisation relate, for example, to experiences of products and services, workplace environment, leadership and social responsibility.

-

2.

Relational drivers of CR. These drivers are also well established in research and categorisation of stakeholder experiences is in terms of relational aspects such as experiences related to how well organisations inform, listen, keep commitments and provide benefits to stakeholders (e.g. Walsh et al. 2009b; Money et al. 2012b)—as well as more negative experiences that relate to the use or abuse of power by organisations (e.g. MacMillan et al. 2004; Money et al. 2012b).

-

3.

Motivational drivers of CR. These drivers are emerging in the literature and build on advances in the study of psychology (e.g. Lawrence and Nohria 2002). While some may see these as a subset of relational approaches, which can include both intrinsic and extrinsic benefits, the authors suggest that a specific exploration of motivational sources allows for a more precise lens to study how CR perceptions develop.

-

4.

Third-party influence drivers of CR. These drivers are experiences that reside in the communications that stakeholders receive from peers and other key influencers. This could include word or mouth, electronic word of mouth, blogging or more traditional advertising and public relations (see for example Edelman 2016; Dyson and Money 2017). While third-party influences are often outside of organisations’ direct control, they are suggested to be a key reputation-building experience, and often include links between friends and family and observational learning (Bandura 1986; Hillenbrand et al. 2011).

While functional and relational drivers are well discussed in CR literature, motivational drivers and third-party influence drivers are less so, and hence necessitate a brief example.

As an example of motivational drivers of CR experiences, the approach utilized by Unilever is exemplified. Unilever’s purpose is the make sustainable living commonplace. Through the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan the company has been able to engage with stakeholders to co-create solutions in relation to sustainability. More specifically, Unilever is exploring stakeholder motivations towards living more sustainably within the context of fulfilling the following drives: (1) drive to Acquire: gain goods and status commensurate with aspirations; (2) drive to Bond: be part of a group that cares for and gives identity; (3) drive for Meaning: have a purpose that is bigger than yourself; drive to Learn: understand the world around us; drive to Defend: protect the things that are important to us (building on Lawrence 2010; Lawrence and Nohria 2002; Ghobadian et al. 2015).

One key learning from the Unilever case has been that employees have been motivated to educate communities about sustainability, while wider society has been motivated by both defending what is important to them, but also gaining status in relation to sustainability. By looking at sustainability and sustainable behaviours as a function of fundamental human motivation, Unilever has differentiated itself from other organisations—and this is perhaps one of the reasons the company has been so successful in this area with—the sustainable living plan winning numerous awards and sustainable living brands growing 50% faster than other Unilever brands that have yet to embrace this approach (Weed 2017).

Finally, the impact of third-party influence drivers has had significant success, in particular, in relation to public health campaigns—such as reduction in drink driving and the increase in seat-belt wearing (e.g. Vecino-Ortiz et al. 2014). In this context, years of messaging from governments regarding the risks and benefits of such behaviours was found to have much less influence than messages given from the perspective of friends and family members—who provide a personal experience or opinion (Dyson and Money 2017). The advent of social media and rating platforms extends the impact of peer-to-peer influence and the authors therefore advocate further study in this regard in relation to both commercial and non-commercial organisations.

The Need for Deeper Exploration of Contingencies and Moderators in CR Research—Speaks to Increased Global Connectivity and the Possibility to Broadcast and Receive Personalised Views Electronically; As Well As to Advances in the Study of Individual and Cultural Differences

Widespread access to electronic information combined with instantaneous connectivity between large numbers of individuals across geographic boundaries, who often strive to live more individualistically and broadcast personalised views easily and globally, exemplifies the importance of contingencies and moderators when studying reputation.

The communications industry, in all its facets, is at the forefront of unprecedented change right across the globe, which requires organisations to be more transparent in their relationships with stakeholders. The availability of personalised electronic communication and the availability of ‘big data’ offer opportunities for organisations to tailor communications towards individual stakeholders in a way that takes account of aspects that are specific to each individual (e.g. cultural background, demographics and personal beliefs), rather than in a blanket fashion or by stakeholder group. This poses both practical and ethical questions about the importance and use of contingency and moderators (Fernandez-Feijoo et al. 2014; Harjoto and Jo 2015).

When considering such contingencies, researchers may want to study moderation between causes and CR, between CR and outcomes, and direct links between causes and outcomes in terms of (but not limited to) the following factors:

-

1.

Characteristics of the perceiver/stakeholder (i.e. the person experiencing, perceiving or behaving in a certain way)—this could link to that person’s values, personality, social axioms, cognitive understanding, socioeconomic status, culture and sense-making etc. While demographic variables are useful, the authors suggest that these measures should be supplemented by specific cognitive and emotive influence factors that may better explain previously undiscovered underlying moderating mechanisms.

-

2.

Characteristics of the messenger (i.e. the entity being experienced or perceived: usually an organisation or third-party influencer)—this could include aspects such as the credibility, intention, trustworthiness, knowledge and social identity of the messenger.

-

3.

Characteristics of the context/relationship (i.e. the meta-characteristics of the context)—this could include the broader context in which the company–stakeholder relationship is framed, for example, a long- or short-term relationship, a conflict-laden relationship or a partnership.

A case example of how contingencies can impact on the outcome of organisational action is illustrated by Elbel et al. (2009): in the context of communicating about calories of meals in fast-food restaurants in New York it was assumed that simply communicating about calorie intake would reduce calorie consumption and associated health risks. While this was the case in some of the neighbourhoods, Elbel et al. (2009) explain that calorie intake increased in the poorest neighbourhoods, which ironically were the ones primarily targeted with this health campaign. Subsequent research showed that in these environments, people were conducting a cost/benefit analysis—i.e. how could they get the most calories for the least money—producing exactly the opposite outcome behaviour than the programme intended. If the design of the campaign and its associated research had included a moderator that took account of factors, such as socioeconomic status and people’s beliefs systems, it may have been able to tailor messages to produce better outcomes.

From a managerial perspective, the importance of transparent, individualised and authentic communication can be understood in relation to factors such as the following (Pain 2017): a need to be empathetic (organisations will need to demonstrate a real understanding and appreciation of the needs both of the planet and the people on it); a clarity of purpose and message (organisations need to know who they are and what they stand for if they are to be seen and heard in today’s media space); and engagement in alliances and collaboration (issues are now bigger than any one individual, government, corporation or country—the world is a highly interconnected place and will require far more collective responsibility than has been the case so far).

Reputation Framework and Outlook on CR Research

Before integrating the insights from Sect. 3 of this article into the novel reputation framework presented below, with the purpose of guiding future studies in this field, a final aspect in CR research needs exploration: CR, at its heart, is typically defined as the perception of a character (Fombrun 1996). It is therefore important that the study of CR integrates advances in knowledge about the nature and development of perceptions and attitudes. Key aspects in this regard relate to advances in the understanding of how cognitive and emotional aspects develop, interact and how they impact on perceptions, in particular perceptions about a character, or characteristic of an entity (Dolcos and Denkova 2014).

Much reputation research is based on the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein 2000; Ajzen 2012), which proposes that emotional reactions result from a cognitive assessment. Other theories, however, suggest that emotional reactions may precede cognitive assessment or occur in parallel and at the very least that cognitive and emotional perceptions influence each other (Pessoa 2013; Braver et al. 2014). The authors therefore propose that CR research takes account of this development and more explicitly differentiates between cognitive and emotional elements in a way that recognises both and aims to categorise CR equally in terms of cognitive and emotional elements as follows:

-

1.

Cognitive aspects—such as beliefs or judgements—can be used for differentiation, as beliefs or judgements are not by their nature ‘positive’ or ‘negative’. For example, a reputation for being highly technical, modern or even competent could be positive or negative depending on the perspective of the person making a judgement. Such cognitive aspects are often explored as perceptions of an organisations ‘personality’ (Davies et al. 2001), but could refer to other characteristics such as the perceived values or temperament of an organisation.

-

2.

Emotional aspects—such as feelings or attitudes—can be used for benchmarking and may be seen as outputs in certain circumstances. Factors that are important in this regard include stakeholder trust in organisations, as well as the level of respect and admiration that stakeholders have for an organisation. This is often explored in terms of what Fombrun et al. (2000) would refer to as emotional appeal.

Integrating cognitive and emotional aspects alongside earlier (in Sect. 3) discussed categorisations of CR outcomes, drivers and moderators, results in the novel reputation framework displayed in Fig. 2. A key factor differentiating reputation from outcomes of reputation in that framework is that the focus of perceptions and feelings with regard to reputation is always the organisation, i.e. how much the organisation is trusted, admired or respected, or the extent to which it is believed to have certain characteristics, i.e. how modern, traditional or innovative it is. Outcomes of CR, on the other hand, relate to stakeholder behaviours, which can be directed towards the organisation or can be directed elsewhere: one of the key messages of this article is that in considering organisational purpose more broadly, consequences may also include behaviours, intentions and end-states, such as prosocial behaviours and the wellbeing of stakeholders, that go beyond more instrumental and organisation-focused behaviours.

As can be seen in Fig. 2, the framework can be explored from an organisation-oriented perspective (in terms of strategic actions, intangible assets and KPIs) as well as from a stakeholder-oriented perspective (in terms of experiences/observations, feelings/beliefs and intentions/behaviours). It is important to note that the authors expect the organisation and stakeholder perspectives to reflect one another as they are two sides of the same coin, concepts that can be seen as equivalent. If relationships flourish—this allows strategic aims to be fulfiled. Causes of CR from an organisation-oriented perspective would translate into strategic actions, while causes of CR from a stakeholder-oriented perspective represent experiences or observations related in some way to these strategic actions. When considering CR, an organisation may consider it as ‘goodwill’ or as an ‘intangible asset’—which from a stakeholder-oriented perspective corresponds to the trust, admiration and esteem in which stakeholders holds an organisation. Finally, in terms of strategic outcomes, an organisation may consider KPIs such as the extent of sustainable consumption, employee engagement or community wellbeing (Money et al. 2009), while for stakeholders, this would translate into behaviours or end-states for each individual stakeholder.

It should also be noted that there is a feedback loop linking outcomes of CR back to causes of CR. In this way, scholars and practitioners are invited to learn from research and current behaviours and use these as inputs to guide future actions. A feedback loop also allows for the calculation of return on investment for certain strategic actions: the cost of a strategic action can be calculated in terms of the benefit of the behaviour it creates. For prosocial behaviours, such as sustainable consumption, it may be possible to link campaigns to litres of water saved, or the amount of waste not going to landfill (Holt and Littlewood 2015). For government-related campaigns, it may be possible to link strategic actions to extended life expectancy, increased health within society and possibly even lives saved—while at the same time exploring the cost and impact of the strategic actions involved. The framework also supports researchers aiming to utilise controlled experiments that could create different experiences for stakeholders and, as such, measure the impact of these actions on outcomes.

Direct Links Between Causes and Consequences of CR: The Role of Corporate Communications

A number of researchers in CR, as well as wider management areas, suggest to directly link what are labelled causes and consequences in the above framework without CR as a mediating variable (Money et al. 2009). The benefit of such approaches is to provide insights that directly link strategic action to observable outcome, without the need to include all explanatory variables. In particular, the exploration of direct impacts may be of use to those exploring the impact of corporate communications in relation to encouraging behavioural outcomes in stakeholders (Saraeva 2017). While corporate communications can be seen as a subset of the relational experiences that may drive CR and its associated consequences in stakeholder perception, it is worth noting that corporate communication (other than other aspects of stakeholder experiences) are under the control of organisations and may therefore form the foundation of campaigns aimed at bringing about positive behaviour change for social or other good. As such, the framework could be used to explore the impact of messages sent by the organisation and other stakeholders and the impact that these messages have on outcomes directly.

In these circumstances, the organisation would be seen to be operating as a messenger—and as such the impact of its message on stakeholder behaviour may or may not be mediated or moderated by CR and other factors. For example, an organisation sending a message to stakeholders in regards to consuming products more sustainably would presumably have a bigger positive impact on stakeholder behaviour if it had a positive and trusted reputation in relation to sustainability issues (than if it were seen to have a reputation for greenwash). The exploration of message–messenger interaction is explored in depth by Saraeva (2017) and the authors warmly welcome studies that seek to more deeply unpack the role of corporate communications and third-party influence and explore the reputation of messengers (be they corporate or third party) as mediators or possibly moderators.

A Note for the Future

In terms of a future outlook on proposed CR research, the authors believe that the concepts and categorisations provided in Fig. 2 will allow us to achieve a number of future ambitions and allow researchers to follow new paths in CR studies, three of which are briefly summarised below.

First, in exploring the outcomes and consequences of CR, the framework integrates different perspectives to explore aspects of organisational purpose. As such, the framework can be utilised to research and manage issues that may by some be perceived as paradoxes: such as short- vs long-term interests; internal vs external change processes, company-oriented vs stakeholder-oriented approaches and organisation vs societal benefits. For such studies, the authors suggest to determine specific KPIs that can be measured simply, in terms of stakeholder behaviour, intention or end-states, and can be traced back to strategic action and stakeholder experiences and observations thereof. Importantly, we suggest that the study and management of reputation can have positive impacts on organisations and stakeholders beyond the corporate sector. In particular, we believe that the management, measurement and evaluation of reputation and communications offer great benefit to government departments and the NGO sector as they often seek to improve stakeholder wellbeing and prosocial behaviour. For this reason, we have endeavoured to ensure that the framework we present in this paper can continue to inform and enhance government communications evaluation frameworks that also seek to causally link outputs such as organisational communication with outcomes such as stakeholder support (Government Communication Service 2016)

Second, in exploring causes or drivers of CR, the framework leverages advances in psychology, which will be of particular use and interest to the relational/perception-based approach to CR: while human nature may be causing many of the problems that the world is currently facing, leveraging a deeper understanding of human motivation can potentially provide solutions in that regard (as exemplified earlier in the Unilever example). As such the framework proposes ways to humanise and influence between stakeholders as a way to build bridges between people as well as between people and business, (Money et al. 2016). The framework also proposes ways to better balance ambitions of business and society and for both to be embedded and measured in stakeholder experience: i.e. rather than just stopping certain behaviours the framework can be used to support starting alternative behaviours and as such can allow business to become more of a force for good.

Third, in terms of research context and research process, the framework allows us to integrate contextual developments, such as a rise in identity politics and the rise and fall of diversity of opinion (i.e. while people tend to talk to more people facilitated through electronic tools, the diversity of opinion often appears smaller). It acknowledges the growing power of stakeholders through social media, and implies a need for more transparency, more honest communication and more connections between corporations and the recipients of CRs (Walsh et al. 2016a, b). Importantly, the framework conceptualises reputation management as a process that has a feedback loop, which allows organisations to be both values and stakeholder led in their purpose; and to rethink the purpose of business from a societal perspective (Waddock 2000), i.e. in terms of setting, co-creating and meeting expectations; and in terms of understanding stakeholders as individuals, citizens or people with a wider purpose than functional roles such as consumers, employees or citizens.

References

Ahearne, M., C.B. Bhattacharya, and T. Gruen. 2005. Antecedents and consequences of customer–company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (3): 574–585.

Ajzen, I. 2012. Martin Fishbein’s legacy: The reasoned action approach. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 640 (1): 11–27.

Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein. 2000. Attitudes and the attitude–behavior relation: Reasoned and automatic processes. European Review of Social Psychology 11 (1): 1–33.

Albert, S., and D.A. Whetten. 1985. Organizational identity. In Research in organizational behaviour, ed. L.L. Cummings, and B.M. Staw, 263–295. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Amit, R., and P.J. Schoemaker. 1993. Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal 14 (1): 33–46.

Anderson, E., and B. Weitz. 1992. The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. Journal of Marketing Research 29 (1): 18–34.

Ansari, S., K. Munir, and T. Gregg. 2012. Impact at the ‘bottom of the pyramid’: The role of social capital in capability development and community empowerment. Journal of Management Studies 49 (4): 813–842.

Arend, R.J. 2013. A heart–mind–opportunity nexus: Distinguishing social entrepreneurship for entrepreneurs. Academy of Management Review 38 (2): 313–315.

Argenti, P.A., and B. Druckenmiller. 2004. Reputation and the corporate brand. Corporate Reputation Review 6 (4): 368–374.

Arnold, J., C. Coombs, A. Wilkinson, J. Loan-Clarke, J. Park, and D. Preston. 2003. Corporate images of the United Kingdom National Health Service: Implications for the recruitment and retention of nursing and allied health profession staff. Corporate Reputation Review 6 (3): 223–238.

Ashforth, B., S. Harrison, and K. Corley. 2008. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management 34 (3): 325–374.

Ashforth, B.E., M. Joshi, V. Anand, and A.M. O’Leary-Kelly. 2013. Extending the expanded model of organizational identification to occupations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43 (12): 2426–2448.

Austin, J.E., and M.M. Seitanidi. 2012. Collaborative value creation: A review of partnering between nonprofits and businesses. Part 2: Partnership processes and outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41 (6): 929–968.

Bagwell, K. 1992. Pricing to signal product line quality. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 1 (1): 151–174.

Balmer, J.M.T. 1998. Corporate identity and the advent of corporate marketing. Journal of Marketing Management 14 (8): 963–996.

Balmer, J.M.T., and S.A. Greyser. 2003. Revealing the corporation. Perspectives on identity, image, reputation, corporate branding and corporate-level marketing. London: Routledge.

Bandura, A. 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bantimaroudis, P., and S.C. Zyglidopoulos. 2014. Cultural agenda setting: Salient attributes in the cultural domain. Corporate Reputation Review 17 (3): 183–194.

Barlow, W.G., and S.L. Payne. 1949. A tool for evaluating company community relations. Public Opinion Quarterly 13 (3): 405–414.

Barnett, M.L., J.M. Jermier, and B.A. Lafferty. 2006. Corporate reputation: The definitional landscape. Corporate Reputation Review 9 (1): 26–38.

Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17 (1): 99–120.

Bartikowski, B., G. Walsh, and S.E. Beatty. 2011. Culture and age as moderators in the corporate reputation and loyalty relationship. Journal of Business Research 64 (9): 966–972.

Basdeo, D.K., K.G. Smith, C.M. Grimm, V.P. Rindova, and P.J. Derfus. 2006. The impact of market actions on firm reputation. Strategic Management Journal 27 (12): 1205–1219.

Beatty, S.E., A.M. Givan, G.R. Franke, and K.E. Reynolds. 2015. Social store identity and adolescent females’ store attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 23 (1): 38–56.

Bennett, R., and R. Kottasz. 2000. Practitioner perceptions of corporate reputation: An empirical investigation. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 5 (4): 224–235.

Berens, G., and C.B.M. van Riel. 2004. Corporate associations in the academic literature: Three main streams of thought in the reputation measurement literature. Corporate Reputation Review 7 (2): 161–178.

Bergh, D.D., D.J. Ketchen, B.K. Boyd, and J. Bergh. 2010. New frontiers of the reputation–performance relationship: Insights from multiple theories. Journal of Management 36 (3): 620–632.

Besiou, M., M.L. Hunter, and L.N. Van Wassenhove. 2013. A web of watchdogs: Stakeholder media networks and agenda-setting in response to corporate initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics 118 (4): 709–729.

Bhattacharya, C., D. Korschun, and S. Sen. 2009. Strengthening stakeholder–company relationship through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics 85: 257–272.

Bhattacharya, C.B., and S. Sen. 2003. Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing 67 (2): 76–88.

Bolger Jr., J.F. 1959. How to evaluate your company image. Journal of Marketing 24 (2): 7–10.

Boyd, B.K., D.D. Bergh, and D.J. Ketchen Jr. 2010. Reconsidering the reputation—Performance relationship: A resource-based view. Journal of Management 36 (3): 588–609.

Brammer, S., G. Jackson, and D. Matten. 2012. Corporate social responsibility and institutional theory: New perspectives on private governance. Socio-Economic Review 10 (1): 3–28.

Braver, T.S., M.K. Krug, K.S. Chiew, et al. 2014. Mechanisms of motivation–cognition interaction: Challenges and opportunities. Cognitive, Affective and Behavioral Neuroscience 14 (2): 443–472.

Bromley, D.B. 1993. Reputation. Image and impression management. London: Wiley.

Bromley, D.B. 2001. Relationships between personal and corporate reputation. European Journal of Marketing 35 (3/4): 316–334.

Broom, G., S. Casey, and J. Ritchey. 2000. Toward a concept and theory of organization–public relationships: An update. In Public relations as relationship management: A relational approach to public relations, ed. J.A. Ledingham, and S.D. Bruning, 3–22. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Brown, T.J. 1998. Corporate associations in marketing: Antecedents and consequences. Corporate Reputation Review 1 (3): 215–233.

Brown, T.J., P.A. Dacin, M.G. Pratt, and D.A. Whetten. 2006. Identity, intended image, construed image, and reputation: An interdisciplinary framework and suggested terminology. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34 (2): 99–106.

Cable, D.M., and M.E. Graham. 2000. The determinants of job seekers’ reputation perceptions. Journal of Organizational Behavior 21 (80): 929–947.

Cai, H., G.Z. Jin, C. Liu, and L.-A. Zhou. 2014. Seller reputation: From word-of-mouth to centralized feedback. International Journal of Industrial Organization 34: 51–65.

Carmeli, A., and A. Tishler. 2004a. The relationships between intangible organizational elements and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal 25 (13): 1257–1278.

Carmeli, A., and A. Tishler. 2004b. Resources, capabilities, and the performance of industrial firms: A multivariate analysis. Managerial and Decision Economics 25 (6/7): 299–315.

Carroll, C. 2009. Defying a reputational crisis—Cadbury’s salmonella scare: Why are customers willing to forgive and forget? Corporate Reputation Review 12 (1): 64–82.

Carroll, C. 2010. Corporate reputation and the news media: Agenda-setting within business news coverage in developed, emerging, and frontier markets. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Carroll, C.E. 2013. Corporate communication and the multi-disciplinary field of communication. In The handbook of communication and corporate reputation, ed. G. Carroll. Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK.

Carroll, C.E., and M. McCombs. 2003. Agenda-setting effects of business news on the public’s images and opinions about major corporations. Corporate Reputation Review 6 (1): 36–46.

Carter, S.M., and T.W. Ruefli. 2006. Intra-industry reputation dynamics under a resource-based framework: Assessing the durability factor. Corporate Reputation Review 9 (1): 3–25.

Caruana, A., and M.T. Ewing. 2010. How corporate reputation, quality, and value influence online loyalty. Journal of Business Research 63 (9): 1103–1110.

Caruana, A., C. Cohen, and K.A. Krentler. 2006. Corporate reputation and shareholders’ intentions: An attitudinal perspective. Journal of Brand Management 13 (6): 429–440.

Caves, R.E., and M.E. Porter. 1977. From entry barriers to mobility barriers: Conjectural decisions and contrived deterrence to new competition. Quarterly Journal of Economics 91 (2): 241–261.

Chang, H.H., Y.-C. Tsai, K.H. Wong, J.W. Wang, and F.J. Cho. 2015. The effects of response strategies and severity of failure on consumer attribution with regard to negative word-of-mouth. Decision Support Systems 71: 48–61.

Christian, R.C. 1959. Industrial marketing… how important is the corporate image? Journal of Marketing 24 (2): 79–80.

Chun, R. 2001. European Journal of Marketing, special edition: ‘Corporate identity and corporate marketing’. Corporate Reputation Review 4 (3): 276–283.

Chun, R. 2005. Corporate reputation: Meaning and measurement. International Journal of Management Reviews 7 (2): 91–109.

Chun, R., and G. Davies. 2010. The effect of merger on employee views of corporate reputation: Time and space dependent theory. Industrial Marketing Management 39 (5): 721–727.

Cloninger, D.O. 1995. Managerial goals and ethical behavior. Financial Practice and Education 5 (1): 50–59.

Cornelissen, J.P., S.A. Haslam, and J.M.T. Balmer. 2007. Social identity, organizational identity and corporate identity: Towards an integrated understanding of processes, patternings and products. British Journal of Management 18 (1): 1–16.

Davies, G., and I. Olmedo-Cifuentes. 2016. Corporate misconduct and the loss of trust. European Journal of Marketing 50 (7/8): 1426–1447.

Davies, G., R. Chun, R.V. da Silva, and S. Roper. 2001. The personification metaphor as a measurement approach for corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review 4 (2): 113–127.

Davies, G., R. Chun, R. daSilva, and S. Roper. 2003. Corporate reputation and competitiveness. London: Routledge.

Davis, R., R. Campbell, Z. Hildon, L. Hobbs, and S. Michie. 2015. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: A scoping review. Health Psychology Review 9 (3): 323–344.

De Chernatony, L. 1999. Brand management through narrowing the gap between brand identity and brand reputation. Journal of Marketing Management 15 (1–3): 157–179.

Deephouse, D. 2000. Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. Journal of Management 26 (6): 1091–1112.

Deephouse, D.L., and S.M. Carter. 2005. An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. Journal of Management Studies 42 (2): 329–360.

Deephouse, D.L., W. Newburry, and A. Soleimani. 2016. The effects of institutional development and national culture on cross-national differences in corporate reputation. Journal of World Business 51 (3): 463–473.

Dolcos, F., and E. Denkova. 2014. Current emotion research in cognitive neuroscience: Linking enhancing and impairing effects of emotion on cognition. Emotion Review 6 (4): 362–375.

Dollinger, M.M.J., P.A. Golden, and T. Saxton. 1997. The effect of reputation on the decision to joint venture. Strategic Management Journal 18 (2): 127–140.

Dowling, G.R. 1986. Managing your corporate images. Industrial Marketing Management 15 (2): 109–115.

Dowling, G.R. 1993. Developing your company image into a corporate asset. Long Range Planning 26 (2): 101–109.

Dowling, G.R. 2004. Corporate reputations: Should you compete on yours? California Management Review 46 (3): 19–36.

Dowling, G.R. 2016. Defining and measuring corporate reputations. European Management Review 13 (3): 207–223.

Dowling, G., and P. Moran. 2012. Corporate reputations: Built in or bolted on? California Management Review 54 (2): 25–42.

Dunne, E. 1974. How to discover your company’s reputation. Management Review 63 (18): 52–54.

Dutton, J., and J. Dukerich. 1991. Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Academy of Management Journal 34 (3): 517–554.

Dutton, J.E., J.M. Dukerich, and C.V. Harquail. 1994. Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly 39: 239–263.

Dyson, T., and K. Money. 2017. Introducing the channel strategy model: How to optimise value from third party influence. Henley Discussion Paper series JMC-2017-01. Henley Business School, University of Reading.

Eberl, M. 2010. An application of PLS in multi-group analysis: The need for differentiated corporate-level marketing in the mobile communications industry. In Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications in marketing and related fields, ed. V.E. Vinzi, 487–514. Berlin: Springer.

Eberle, D., G. Berens, and T. Li. 2013. The impact of interactive corporate social responsibility communication on corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics 118 (4): 731–746.

Edelman (2016) Trust Barometer. www.edelman.com/insights/intellectual-property/2016-edelman-trust-barometer. Accessed 31 July 2017.

Einwiller, S.A., C.E. Carroll, and K. Korn. 2010. Under what conditions do the news media influence corporate reputation? The roles of media dependency and need for orientation. Corporate Reputation Review 12 (4): 299–315.

Elbel, B., R. Kersh, V.L. Brescoll, and L.B. Dixon. 2009. Calorie labelling and good choices: A first look at the effects on low-income people in New York City. Health Affairs 28 (6): 1110–1121.

Ettorre, B. 1996. The care and feeding of a corporate reputation. Management Review 85 (6): 39–42.

Fernandez-Feijoo, B., S. Romero, and S. Ruiz. 2014. Effect of stakeholders’ pressure on transparency of sustainability reports within the GRI framework. Journal of Business Ethics 122 (1): 53–63.

Fillis, I. 2003. Image, reputation and identity issues in the arts and crafts organization. Corporate Reputation Review 6 (3): 239–251.

Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fombrun, C.J. 1996. Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Fombrun, C. 2012. The building blocks of corporate reputation; definitions, antecedents, consequences. In The Oxford handbook of corporate reputation, ed. M. Barnett, and T. Pollock. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fombrun, C., and M. Shanley. 1990. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal 33 (2): 233–258.

Fombrun, C., and C. van Riel. 1997. The reputational landscape. Corporate Reputation Review 1 (1/2): 5–13.

Fombrun, C., N. Gardberg, and J. Sever. 2000. The reputation quotient: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management 7 (4): 241–255.

Fombrun, C.J., L.J. Ponzi, and W. Newburry. 2015. Stakeholder tracking and analysis: The Reptrak® system for measuring corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review 18 (1): 3–24.

Foreman, P., D. Whetten, and A. Mackey. 2013. An identity-based view of reputation, image, and legitimacy: Clarifications and distinctions among related constructs. In The Oxford handbook of corporate reputation, ed. M. Barnett, and T. Pollock. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freeman, R.E. 1984. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Freeman, R.E. 2010. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fryxell, G.E., J. Wang, and W. Jia. 1994. The Fortune corporate ‘reputation’ index: Reputation for what? Journal of Management 20 (1): 1–14.

Gabbioneta, C., D. Ravasi, and P. Mazzola. 2007. Exploring the drivers of corporate reputation: A study of Italian securities analysts. Corporate Reputation Review 10 (2): 99–123.

Gardberg, N.A., and C.J. Fombrun. 2002. The global reputation quotient project: First steps towards a cross-nationally valid measure of corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review 4 (4): 303.

Gardberg, N.A., P.C. Symeou, and S.C. Zyglidopoulos. 2015. Public trust’s duality in the CSP–reputation–financial performance relationship across countries. Academy of Management Proceedings (Meeting Abstract Supplement) 2015 (1): 15705.

Gardberg, N.A., S.C. Zyglidopoulos, P.C. Symeou, and D.H. Schepers. 2017. The impact of corporate philanthropy on reputation for corporate social performance. Business and Society. doi:10.1177/0007650317694856.

Garnelo-Gomez, I., D. Littlewood, and K. Money. 2015. Understanding the identity and motivations of sustainable consumers: A conceptual framework. Paper presented at the British Academy of Management Conference, Portsmouth, UK, September 2015.

Gassenheimer, J.B., F.S. Houston, and J.C. Davis. 1998. The role of economic value, social value, and perceptions of fairness in interorganizational relationship retention decisions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 26 (4): 322–337.

Ghobadian, A., K. Money, and C. Hillenbrand. 2015. Corporate responsibility research: Past–present–future. Group & Organization Management 40 (3): 271–294.

Gioia, D.A., and J.B. Thomas. 1996. Identity, image, and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during strategic change in academia. Administrative Science Quarterly 41 (3): 370–403.

Goldberg, M.E., and J. Hartwick. 1990. The effects of advertiser reputation and extremity of advertising claim on advertising effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research 17 (2): 172–179.

Government Communication Service. 2016. Government communication plan 2016/17. Retrieved August 30, 2017, from https://gcs.civilservice.gov.uk/static/government-comms-plan-2016/files/assets/common/downloads/publication.pdf.

Greenwood, M. 2007. Stakeholder engagement: Beyond the myth of corporate responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 74 (4): 315–327.

Grunig, J.E. 1993. Image and substance: From symbolic to behavioral relationships. Public Relations Review 19 (2): 121–139.

Hall, R. 1992. The strategic analysis of intangible resources. Strategic Management Journal 13 (2): 135–144.

Hall, R. 1993. A framework linking intangible resources and capabiliites to sustainable competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal 14 (8): 607–618.

Hammond, S.A., and J.W. Slocum Jr. 1996. The impact of prior firm financial performance on subsequent corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics 15 (2): 159–165.

Harjoto, M.A., and H. Jo. 2015. Legal vs. normative CSR: Differential impact on analyst dispersion, stock return volatility, cost of capital, and firm value. Journal of Business Ethics 128 (1): 1–20.

Helm, S. 2007. The role of corporate reputation in determining investor satisfaction and loyalty. Corporate Reputation Review 10 (1): 22–37.

Helm, S. 2011a. Corporate reputation: An introduction to a complex construct. In Reputation management, ed. S. Helm, K. Liehr-Gobbers, and C. Storck. Berlin: Springer.

Helm, S. 2011b. Employees’ awareness of their impact on corporate reputation. Journal of Business Research 64 (7): 657–663.

Helm, S. 2013. A matter of reputation and pride: Associations between perceived external reputation, pride in membership, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. British Journal of Management 24 (4): 542–556.

Helm, S., and J. Tolsdorf. 2013. How does corporate reputation affect customer loyalty in a corporate crisis? Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 21 (3): 144–152.

Herbig, P., and J. Milewicz. 1993. The relationship of reputation and credibility to brand success. Journal of Consumer Marketing 10 (3): 18–24.

Hillenbrand, C., K. Money, and A. Ghobadian. 2011. Unpacking the mechanism by which corporate responsibility impacts stakeholder relationships. British Journal of Management 24 (1): 127–146.

Holt, D., and D. Littlewood. 2015. Identifying, mapping, and monitoring the impact of hybrid firms. California Management Review 57 (3): 107–125.

Hong, S.Y., and S.-U. Yang. 2009. Effects of reputation, relational satisfaction, and customer–company identification on positive word-of-mouth intentions. Journal of Public Relations Research 21 (4): 381–403.

Hosmer, L.T., and C. Kiewitz. 2005. Organizational justice: A behavioral science concept with critical implications for business ethics and stakeholder theory. Business Ethics Quarterly 15 (1): 67–91.

Huang, Y.H. 1998. Public relations strategies and organization? Public relationships. In Association for education in journalism and mass communication, Baltimore, MD, USA, August 5–8.

Illia, L., and F. Lurati. 2006. Stakeholder perspectives on organizational identity: Searching for a relationship approach. Corporate Reputation Review 8 (4): 293–304.

Johnston, K.A., and J.L. Everett. 2012. employee perceptions of reputation: An ethnographic study. Public Relations Review 38 (4): 541–554.

Johnston, T. 2002. Superior seller reputation yields higher prices: Evidence from online auctions. Marketing Management Journal 13 (1): 108–117.

Kiousis, S., C. Popescu, and M. Mitrook. 2007. Understanding influence on corporate reputation: An examination of public relations efforts, media coverage, public opinion, and financial performance from an agenda-building and agenda-setting perspective. Journal of Public Relations Research 19 (2): 147–165.

Kitchen, P.J., and A. Laurence. 2003. Corporate reputation: An eight-country analysis. Corporate Reputation Review 6 (2): 103–117.

Korschun, D. 2015. Boundary-spanning employees and relationships with external stakeholders: A social identity approach. Academy of Management Review 40 (4): 611–629.

Korschun, D., and S. Du. 2013. How virtual corporate social responsibility dialogs generate value: A framework and propositions. Journal of Business Research 66 (9): 1494–1504.

Korschun, D., C.B. Bhattacharya, and S.D. Swain. 2014. Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. Journal of Marketing 78 (3): 20–37.

Kreiner, G.E., and B.E. Ashforth. 2004. Evidence toward an expanded model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25 (1): 1–27.

Kreps, D.M., and R. Wilson. 1982. Reputation and imperfect information. Journal of Economic Theory 27 (2): 253–279.

Lange, D., P.M. Lee, and Y. Dai. 2011. Organizational reputation: A review. Journal of Management 37 (1): 153–184.

Lambe, C.J., C.M. Wittmann, and R.E. Spekman. 2001. Social exchange theory and research on business-to-business relational exchange. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 8 (3): 1–36.

Lawrence, P.R. 2010. Driven to lead: Good, bad and misguided leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lawrence, P.R., and N. Nohria. 2002. Driven: How human nature shapes our choices. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Leach, M., J. Rockström, P. Raskin, et al. 2012. Transforming innovation for sustainability. Ecology and Society 17 (2): 11–16.

Lee, Y., W. Wanta, and H. Lee. 2015. Resource-based public relations efforts for university reputation from an agenda-building and agenda-setting perspective. Corporate Reputation Review 18 (3): 195–209.

Lewellyn, P.G. 2002. Corporate reputation: Focusing the zeitgeist. Business and Society 41 (4): 446–455.

Liedong, T.A., A. Ghobadian, T. Rajwani, and N. O’Regan. 2015. Toward a view of complementarity: Trust and policy influence effects of corporate social responsibility and corporate political activity. Group & Organization Management 40 (3): 405–427.

Littlewood, D. 2014. ‘Cursed’communities? Corporate social responsibility (CSR), company towns and the mining industry in Namibia. Journal of Business Ethics 120 (1): 39–63.

Love, E.G., and M. Kraatz. 2009. Character, conformity, or the bottom line? How and why downsizing affected corporate reputation. Academy of Management Journal 52 (2): 314–335.

Love, E.G., and M.S. Kraatz. 2017. Failed stakeholder exchanges and corporate reputation: The case of earnings misses. Academy of Management Journal 60 (3): 880–903.

Maathuis, O., J. Rodenburg, and D. Sikkel. 2004. Credibility, emotion or reason? Corporate Reputation Review 63 (4): 333–345.

MacLeod, J.S. 1967. The effect of corporate reputation on corporate success. Management Review 56 (10): 67–71.

MacMillan, K., K. Money, and S.J. Downing. 2000. Successful business relationships. Journal of General Management 26 (1): 69–83.