Abstract

This research work investigates the development of interpersonal trust between the client and the consultant during the consulting process. It gives a conceptual outline of the trust building dimensions in the consultant-client relationship in terms of propensity to trust, perceived trustworthiness and the conditions of the trust situation with referring to the integrated trust model of Mayer, Davis and Schoorman. The research findings are enhanced by a qualitative practical investigation to provide a further context-specific concretization. Even though the implications from the practical investigation are in main parts congruent with the conceptual findings, it turned out that trust as a social mechanism is difficult to be grasped during practical interviews, why a conceptual foundation is indispensable to capture the total trust spectrum. This work shows that the trustworthy factors of abilities, integrity and benevolence are relevant for building interpersonal trust between the consultant and client, whereas a lack of ability-related trustworthiness cannot be compensated by the others. It is identified that signaling same-goal-orientation with the client and demonstrating a supportive role for the client’s interests are key factors for building trust by the consultant. It is also highlighted that a transparent working approach of the consultant is vital to reduce the client’s uncertainty and to promote trust building.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Significance of Trust in the Consulting Process

Consulting is often characterized as a trust object. The client needs to rely on the expertise promised by the consultant in advance of the project and the consultant’s performance is also difficult to be evaluated even after finishing the project (Woratschek 1996; Mohe 2003). The lack of trust is considered as a main cause for failures of consulting engagements. The trust matter has gained increasing relevancy for the client company and, consequently, for the consultancy when, at the same time of a growing consulting market, also the number of unsuccessful consulting projects as well as frivolous behavior of the consultants significantly increased (Greschuchna 2006).

Consulting in the sense of this research contribution is defined in accordance to Nissen as follows (Nissen 2007):

Consulting is a professional service that is provided by one or more persons, who typically have the required expertise to solve the problem at hand and are hierarchically independent of the client organization. The consulting engagement is limited in time, financially compensated and has the objective to define, structure and analyze business issues of the client organization interactively with the client’s employees and to develop corresponding solutions as well as to implement them in close cooperation with the client if requested.

Despite the various areas of consulting engagements, there are certain characteristics that are typical for consulting services. The nature of consulting is seen as a weakly pre-determined and complex domain. The actual consulting service as the product is to be concretized while the consulting processes are carried out based on interactions between the consultant and the client. The way to the final consulting result is significantly driven by several bases of expectations from both the client and consulting organization (Jacobsen 2005). A certain portion of risk is always inherent to consulting projects, what originates from the structural input-output uncertainty that is typical for services with incorporating the external factor (Maleri 1997).

Consulting as a service has an intangible character, which implies a high portion of contingencies (Jacobsen 2005). Glueckler and Armbruester have identified institutional uncertainty and transactional uncertainty as the two most significant types of uncertainty in the consulting sector (Glückler and Armbrüster 2003). Institutional uncertainty derives from the lack of formal institutional standards like industry principles and codes of conduct. Transactional uncertainty stems from confidentiality of information, service-product characteristics and the interdependent and interactive character of the co-production of consultants and client (Glückler and Armbrüster 2003). The consultant’s possibilities of opportunistic behavior and moral hazard make the client feel uncertain (Gillespie 2003). There is substantial risk during the consultant engagement that his actions and decisions are to the detriment of the client organization. The client is faced with the hazard of hidden intentions by the consultant, which could only be revealed after the contracting phase when the consulting project is in progress (Kralj 2004). This is in one line with the further typical agency problems of hidden actions (opportunistic behavior of the consultant) or hidden characteristics (inadequate expertise and capabilities of the consultant) (Barchewitz and Armbrüster 2004).

Irrespective of the actual role of the consultant, whether he acts more as a coach or as an expert, the consulting situation is always determined by the clash of two parties. Consequently, the interactions between consultants and clients and, hence, the focus on individuals are the crucial drivers for consulting success. Constant communication is required to ensure that the specific context of the client organization can be incorporated into the development and implementation of solutions (Sommerlatte 2000). Consulting is thus about forming relationships. The consultant needs to create a productive and sustainable relationship with the individuals of the client’s company to achieve success (Coers and Heinecke 2002).

The high interaction need during a consulting process is the reason why a trustful cooperation has a significant impact on the consulting process (Jeschke 2004). A certain level of personal proximity is to be admitted by the client to enable the consulting engagement to deliver results that are specific for the client context. However, the consultant’s own economic interest to maximize profit through the engagement and the hazard of opportunistic behavior indicate the need for caution and control. The client is therefore faced with critical attribution problems of what level of freedom can be granted to the consultant (Müller et al. 2006). As mentioned, these problems are not controlled by a superior instance like an industry authority. Due to that fact, trust is a critical dimension in the relationship between consultant and client and therefore has an existential role in the consulting processes (Höner 2008). Studies by Covin and Fisher analyzing the success of consulting projects have shown that a lack of trust is the frequent cause for a failure of a consulting engagement (Covin and Fisher 1991). Dean points out that trust should not only be seen as a soft factor, but also as a hard prerequisite for the consultant to enable transformations and impact in the client organization. The consultant’s profound expertise and methodologies would not have any effect if they cannot flow into a sound and trustworthy client-consultant relationship (Dean 2005).

2 Research Context, Specification and Methodology

2.1 Basic Perspectives on the Comprehension of Trust

The investigation of interpersonal trust development in the constellation of the consultant-client relationships requires first to constitute the relevant conceptual basis for that research matter. The trust phenomenon is scientifically approached by different disciplines, why there is no consistent comprehension of the trust terminology and, consequently, no overall conception of trust that is universally accepted (Ripperger 2003; Jehle 2001; Klaus 2002). In the academic literature there are numerous definitions for trust. Castaldo has identified 72 different approaches for that definitional matter (Castaldo 2002). For the present research work the essential scientific cornerstones of the trust research are mentioned.

The groundwork of trust research was made within the psychological discipline with the primary focus on the characteristics of individuals. In that regard, the preconditions for interpersonal trust have been investigated and it is argued from a behavioral-oriented and preference-oriented perspective (Klaus 2002). This psychological orientation was predominantly influenced by the behavioral-oriented studies of Deutsch, who provided major contributions with his experiments in the fields of game theory when investigating the motivational effects of cooperative, competitive and individualistic patterns on the decisions of individuals in different situations of interactions (Deutsch 1958, 1960). Trust in the conception of Deutsch is interpreted as observable, situation-dependent and voluntary behavior of individuals (Deutsch 1962). Deutsch stated that “…the problem of trust arises from the possibility that if, during cooperation, each cooperator is individually oriented to obtain a maximum gain at minimum cost to himself (without regard to the gains or costs to the other cooperators), cooperation may be unrewarding for all or for some” (Deutsch 1960).

Next to the psychological perspective the sociological view on trust enhances this conception with perceiving trust as a feature in social relationships (Moorman et al. 1993). Luhmann provided a fundamental contribution to the trust conception in this sociological perspective (Luhmann 1989). In conjunction with his system-theoretical comprehension, Luhmann perceived trust as a mechanism to reduce complexity (Luhmann 1989) which occurs through the adoption of specific expectations about the future behavior of the interaction partner. This positive expectation is selected amongst a range of possibilities. Complexity is absorbed by trust as someone who grants trust acts as if the trustee’s actions are to a certain extent predictable (Lane 1998). Trust is thus perceived as mechanism that overcomes “the problem of time” with bridging uncertainty in the face of imperfect information. Due to the given problem of time and knowledge, trust is a risky investment because it requires a risky pre-commitment (Luhmann 1979).

In 1995, Mayer, Davis and Schoormann provided a significant contribution to the comprehension of trust in the economic science (Mayer et al. 1995). The term “willingness to be vulnerable” is in the focus of their trust conception. Their model of trust, which is relating to the trust phenomenon in dyadic organizational interaction processes, has been frequently apprehended also in other disciplines of trust research (Kilduff 2006). Mayer et al. considered trust between individuals and also discussed attributes of the trustor, the trustee, the specific situations as well as the behavior that follows a trust relation. As a result, their model integrates determinants, effects and feedback mechanism of trust. In course of their investigation, Mayer et al. integrated insights from trust conceptions of different disciplines and portrayed them in the organizational context. Their comprehension of trust is applicable to any relationship with a person that is assumed to act intentional. The constitutive element of trust is hereby seen in the perception that the trustee can deliberately choose his reaction. This implies that the trustee has always the possibility to honor the granted trust relation or to disappoint it (Mayer et al. 1995).

2.2 Trust Conception for This Research Work

The trust comprehension in this research work refers to the trust concept of Mayer et al. This model concurs with the given thematic consulting context that suggests to investigate trust based on both the characteristics of individuals as well on the level of social relationships between the involved individuals. The conceptual model therefore allows considering the processual perspective of trust development and its dynamics that take effect in the different developing stages of the consulting project. One of the crucial conceptual orientations of their model is that they perceive trust to go beyond a pure dispositional facet that is “trait-like”, but to be also an aspect of relationship. This implies that trust varies across relationships (Mayer et al. 2007). Moreover, the trust model of Mayer et al. integrates both multi-level and cross-level approaches of trust that allow the investigation of interpersonal trust relations within an organization as well as between two separated organizations, as being relevant for the consulting context (Mayer et al. 2007).

The trust model of Mayer et al. has seen significant scientific dedication in consecutive research works, both in empirical and theoretical terms (with showing more than 16,000 scientific citations in Google Scholar by May 2017). Mayer et al. took on these substantial scientific reflections with formulating a subsuming research work in 2007 that also integrates advances and further concretizations of their trust model (Mayer et al. 2007).

Mayer et al. basically defined trust as follows:

The willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective to the ability to monitor or control the other party (Mayer et al. 1995).

In their model they highlighted the importance of the propensity to trust. If there is no information about the interaction partner available, the propensity to trust determines the portion of trust from the trustor. The propensity to trust hereby describes a generalized expectation with regard to the trustworthiness of another person, which is stable throughout different situations. Propensity to trust is assumed to influence how much trust one has for a trustee prior to the availability of data on that particular party (Mayer et al. 1995).

If information about an interaction partner is available then the granted trust depends on the perceived trustworthiness of the specific trustee as well as on the trustor’s propensity to trust. In their model they assumed that trustworthiness can be explained through a function of perception about the ability, benevolence and integrity of the trustee. If the trustor feels that one of those components is only weakly shaped at the potential trustee, this impairs the potential to build up a trust relation (Mayer et al. 1995).

The fundament of a trust decision of human beings is characterized as “risk taking in relationship”, which is assumed to be a function of trust and the perceived risk (Mayer et al. 1995). Based on the consequences of a trustful behavior the trustor modifies the perceived trustworthiness of the trustee. The outcome of the “risk taking in the relationship” results in an updating process of the original estimation of the ability, benevolence and integrity of the trustee. Any negative or positive feedback from the interaction has therefore direct effect on the trust relation for the subsequent situation of interaction (Mayer et al. 1995).

With constituting the relevant conceptual baseline and definition of trust for this research work, it is also vital to delimit trust from other essential conceptual terms. Mayer et al. hereby differentiate trust from cooperation, confidence and predictability. With regard to cooperation, the distinction to trust is often misconstrued. Trust can frequently lead to cooperation. However trust is not a necessary precondition for it, as cooperation does not always put a party on risk. To bring the cooperative behavior in relation with trust, there needs to be vulnerability as a hard pre-requisite (Mayer et al. 1995). There is also an amorphous relation of trust with the term confidence in the history of trust research. Mayer et al. hereby integrate the proposed conceptual distinction of Luhmann when he argued that for trust a relevant portion of risk needs to be recognized and assumed, while this is not the case with confidence. With the trust decision one chooses an action in preference to others in spite of the possibility of being disappointed by others. With confidence one does not consider alternatives (Mayer et al. 1995; Luhmann 1988). Next to this, both trust and predictability are means of uncertainty reduction. As trust refers to the risk the trustor has based on the vulnerability that is subject to the trustee’s behavior, predictability is mainly driven by general and external factors that let the counterparty derive the probable behavior of the other (Mayer et al. 1995).

2.3 Research Specification

Based on the comprehension of trust as quoted in the previous section this research work investigates interpersonal trust in the consultant-client relationship during the consulting process and dedicates to the following research question:

What are the influencing factors for interpersonal trust development between the consultant and the client during the consulting process?

Hereby, the interpersonal trust position is regarded as dependent variable. For that purpose it will conceptually break down the examination of the interpersonal trust relation in the trust building factors of propensity to trust, perceived trustworthiness and the conditions of the trust situation. The investigation of perceived trustworthiness will be further segmented in its determining factors of personal characteristics and behavior-related factors. An embedment in the specific context of the consulting process is essential to ensure that the findings consider the concrete social environment. The role of the consultant defines his position and his level of power in the consultant-client relationship and, therefore, delineates the potential social context in which a trust situation can occur.

A target-oriented and meaningful investigation of that thematic research focus also requires the delimitation of aspects that are not considered as scope of investigation. This research work concentrates on the interpersonal dimension of trust between the consultant and the client. It does not take up the generation and the dynamics of organizational or systemic trust towards the client organization or the consultant organization, which might be constituted by their reputation or by the experience-based trust with the organization as such. Organizational trust, however, is integrated in this research work to the extent that it has deriving character for the interpersonal trust relation. Moreover, this research work focuses on the trust development during the actual consulting project. It does not refer to a relationship between the consulting organization and the client organization beyond that process. As a consequence of that, the effect of trust at the client’s selection process of consultants is not a part of this work. Further-on, this research concentrates on those consulting projects that require a minimum level of interaction between the consultant and the client to produce the consulting result. The explanations and findings of this work will be less meaningful for consulting projects in which the consultants act mainly independently, what might be the case when the consultant is engaged as assessor or independent surveyor.

After having specified the research focus, related work will now be reviewed.

2.4 Related Work

Greschuchna provided an investigation of trust in the consulting context. She focused primarily on the hiring phase of consulting services from the perspectives of small and mid-sized client companies, which were also the basis of her empirical investigation. The objective of her research work was the analysis of the role of trust in the selection process of a consulting company by the clients. It was about to determine which factors influence the client’s perception of trust towards the consultancy at the initial contact and what impact trust has on the engagement decision. She primarily investigated what driving factors in conjunction with organizational trust towards the consulting company do matter. Greschuchna stated that she sees further need to investigate trust during the actual consulting process phase and specifically the dynamics of trust between the client and the consultant (Greschuchna 2006).

A further contribution to the investigation of trust was elaborated by Mencke focusing on trust in social systems and consulting. He provided an analysis of the fundamentals of trust in social systems and applied this to the consulting processes carried out at small- and mid-sized companies. His analysis approach was driven by the system-theoretic orientation. This theoretic orientation bases on the assumption that social complexities and, therefore, social mechanisms such as trust cannot be controlled or influenced by the individuals (Mencke 2005). Due to his theoretic orientation, he could not fully explain the relevancy of interpersonal dynamics and characteristics for the development of interpersonal trust.

In the book “The trusted advisor” Maister, Green and Galford provided practical guidelines for consultants how to achieve a trusting relation with the client in the consulting process. The statements quoted in the book originate from the authors’ own consulting experiences. They gave meaningful insight how consultants could behave in various situations in order to build or maintain a trustworthy position. In case studies and training sections they provided concrete instructions how to deal with clients. Using a practical model they illustrate the steps the consultant would need to take in order to establish and develop a trustful relationship (Maister et al. 2000). This literature represents a valuable practical source of insights into trust development, but the authors do not relate to a specific theoretical model or empirical evidence.

2.5 Research Methodology

Trust is perceived as a complex research object, as it needs to be considered in the wide set of psychological and sociological perspectives. The trust relation as a social facet of the individuals is difficult to be measured and reflected. This suggests that research on interpersonal trust requires a respective theoretical dedication in the first stage. The elaboration of profound statements about the influential factors for the trust relation in the consultant-client relationship has to integrate trust into the social scheme of consulting processes. Only based on that social-analytical framework, one is in a position to capture a holistic picture about the trust relation and the dynamics of trust during the consulting process. Theory-building from a pure quantitative empirical approach would not capture the total of social complexity that is inherent in the interactions of human agents of a consulting project.

Next to that, a qualitative practical analysis is conducted for the purpose of enrichment and concretization of the research topic. For that empirical investigation, it is not intended to conduct an overall empirical validation of hypotheses derived from the theoretic statements. Instead, the empirical approach follows an open explorative consideration of the research topic and is, in general, consecutive to the theoretical conception that has guiding and structuring character for the design of this empirical part. This practical investigation is conducted by using the qualitative approach based on semi-structured expert interviews referring to real practical experiences in consulting projects. Hereby, four consultants and four client employees that have at least 5 years direct experience of involvement in various consulting projects were interviewed.

3 Conceptual Specification of Interpersonal Trust Development in the Consultant-Client Relationship

This section outlines the application of the trust model of Mayer et al. on the interpersonal trust development between the consultant and the client. To investigate the mechanism of the trust building the individual characteristics of the client and the consultant as interaction partners, their relationship as well as situation-specific aspects have to be taken into consideration. The individual characteristics of the interaction partners have to be reflected by the propensity to trust on the side of the trust subject as well as the trustworthiness of the trust object (Mayer et al. 1995, 2007).

3.1 Occurrence of a Trust Situation

With investigating how the development of interpersonal trust between the consultant and the client occurs, it is vital to outline the context in which a trust situation happens. It will be described how the conceptual understanding of the trust relevancy in this research work is represented by the situations in the course of the consultant-client relationship.

The fundament of a trust decision is characterized in the applied model as “risk taking in relationship”, which is assumed to be a function of trust and the perceived risk (Mayer et al. 1995). Therefore, trust becomes relevant in those situations that are uncertain with regard to an outcome of an event or behavior. The conceptual analysis of trust building therefore refers to situations in which subjective uncertainty on side of the consultant or client as potential trustor is given. Basically, the consulting process is affected by various aspects of uncertainty. As basically pointed out in Sect. 1, consulting as a service has an intangible character, which results in structural input-output risks and therefore implies a high portion of contingencies (Jacobsen 2005). Also the consultant has to cope with subjective uncertainty in the relationship with the client. There is uncertainty concerning the quality and correctness of information he is given by the client employees as well as the expertise and competencies of the client that matter for the consulting project. Next to this, there is also uncertainty for the consultant that his engagement is misused by the client for the political game within the client organization or that the client follows hidden motives with the consultant engagement. As a result the analysis of trust building refers to those situations of the consultant-client relationship in which the consultant and the client are faced with subjective uncertainty about the motives and intentions and consequently the behavior of the other party.

The next aspect of a potential trust situation is that the potential trustor is vulnerable when entering a trust situation, as that could cause potential damage to him (Mayer et al. 1995). Here, only the perceived vulnerability matters, which originates from the individual assessment of potential positive or negative outcomes of the respective situation (Späth 2007). On the client side there is a substantial risk of damage since the client has to cope with the economic consequences of the consulting outcome. Moreover, potential damage could also occur to the level of individuals of the client organization, when the outcome of a consulting project results in the loss of allocative or authoritative resources for some client employees. Damage for the consultant can arise regarding their reputation and the loss of potential follow-up business. This might be caused by an unsuccessful consulting outcome due to sanctioning behavior of the client employees or the misuse of the consulting role.

A further important requirement can be derived from the trust definition of Mayer et al. with referring to the term “willingness” to be vulnerable. This implies that there needs to be freedom to decide on part of the trustor. Trust as a social mechanism can only be granted when the consultant or the client in the role of a trustor can make the trust decision voluntarily. The trusting consultant or client need to have the possibility to determine on their own how to behave in the context of the trust situation. This refers to their freedom to decide how they dispense the level of control and supervision towards the interaction partner. Consequently, those situations of consultant-client interactions are not to be comprehended as trust situation in which it is predetermined or prescribed how they have to behave. Trust as intentional construct will for instance not evolve in situations in which the client employee is e.g. directed by hierarchical authorities or processual instructions of the client organization to act or behave in a certain way. Overall it has to be stated that the trust decision cannot be enforced.

3.2 Propensity to Trust of the Trust Subject

The interpersonal trust building is at first grounded on the characteristics of the trustor as the actor who is supposed to give trust to somebody in a specific situation. Interpersonal trust has its fundament in the personality disposition of that trustor. This personality disposition is approached by Mayer et al. as the propensity to trust. It has influence on how much trust the trustor has for a trustee unless he has direct and relevant information about the interaction partner available. Propensity to trust is also described as the general willingness to trust others and has high relevance in terms of building initial trust (Mayer et al. 1995). As soon as further information about the interaction partner is available this experience will successively undermine the significance of propensity to trust (Nooteboom and Six 2003). Accordingly, Mayer et al. state that “time” generally plays an important role in the meaningfulness of the variables in the model. Propensity to trust, as a dispositional quality, would be an important factor at the very beginning of the relationship, whereas judgements of ability and integrity would form relatively quickly in the course of the relationship (Mayer et al. 2007).

Therefore, in a consultant-client relationship the degree of trust that can evolve is at first determined by that propensity to trust. This is a characteristic of the trusting consultant and client. They show higher propensity to trust when they have inner security in the sense that they have the respective level of self-assurance that enables them to encounter the potential disappointment of the trust relation with fortitude. Propensity to trust as a stable “within-party factor” of the trusting consultant and client therefore determines the likelihood that they will trust the interaction partner unless they made direct experience with each other in the consulting process (Mayer et al. 1995). It describes the general willingness of the consultant or the client to trust others. As people in general differ in their inherent propensity to trust, this also refers to the variety of different personalities that come up in the role of the consultant and the client. The propensity to trust depends on the different developmental experiences, personality types and cultural backgrounds of the individual client employees and consultants. Some of them could show the extreme case of frequently granting blind trust, whereas some of them show unwillingness to trust also in favorable circumstances during the consulting project (Mayer et al. 1995).

Propensity of trust has particular significance for trust building when the client and consultants have only a low spectrum of information available about each other. In a lot of projects, the client and the consultant come together as two strangers, as the consultant is temporarily engaged for solving a specific problem of the client organization and he is considered as an outsider of the client organization. This leads to the situation that in many cases the consultant and client do not know each other when the consulting project starts. Propensity of trust is therefore ascribed with high relevance in terms of building initial trust in the entry phase of the consulting process. With evolvement of the relationship between the consultant and the client, situation-specific patterns and experiences gain in importance. Certainly, the context of missing acquaintance does not apply in situation where the consultant is engaged for a follow-up project. Here, the dominance of propensity to trust for an initial trust building is compensated already by the direct knowledge of each other.

Propensity to trust is considered to be a relatively stable personal feature of the respective consultant and the client acting as trustor. It is regarded as to be hardly influencable. The dynamics of interpersonal trust position in course of the consulting process is therefore rather driven by the actual trustworthiness of the trust object as well as situation-specific factors. However for empirical investigations of trust situations the propensity to trust needs to be taken into account as it provides important insight into the sources of trust building in the respective situation.

3.3 Trustworthiness of the Trust Object

Next to the propensity to trust, the decision whether trust can be granted is essentially determined by attributes of the interaction partner as trust object (trustee). The emergence of trust in a relationship is hereby not necessarily triggered by the actual goodness of the trustee’s character, motives or intentions. Instead, it is crucial how the potential trustor perceives those attributes. The perception of those attributes determines the level of trustworthiness and consequently the potential of building trust to the interaction partner (Mayer et al. 1995). Mayer et al. provided a meaningful subsumption of factors for trustworthiness based on their interdisciplinary trust research (Mayer et al. 1995). They resume that the following three characteristic dimensions of the trustee determine his trustworthiness: ability, integrity and benevolence (Mayer et al. 1995). Each characteristic “… contributes a unique perceptual perspective from which to consider the trustee, while the set provides a solid and parsimonious foundation for the empirical study of trust for another party” (Mayer et al. 1995).

The question if and to what extent interpersonal trust between the consultant and the client can be built is significantly determined by that trustworthiness of the potential trustee. Also here it is crucial how the trustor perceives those trustworthy attributes of the interaction partner with utilizing the available information to build either positive or negative expectations of the behavior of the other. The trustworthy attributes then guide the consultant and the client in the trust decision whether the other has the intention and motives that the resulting actions will not cause damage to the trusting consultant and client or even result in a beneficial state for him. The trustee is then also expected to relinquish opportunistic behavior.

Ability as an attribute of the interaction partner refers to the skills, competencies and characteristics that enable him to have influence within some specific domain. For the relevancy of trustworthiness, this domain needs to be important for the consulting project. This might refer to competence in some functional area in which related project tasks are to be carried out. However, this also implies that this trustee could have little aptitude, training or experience in another area that does not matter for that specific consulting process and the trust situation (Mayer et al. 1995). Based on the conceptual understanding, a trust situation is given regarding the correct statement of the consultant and the client about their abilities. Trust becomes thus relevant when the actual abilities of the interaction partner cannot be fully assessed and one has to rely on information from the interaction partner himself or from a third party. Here, trust refers to the reliability of information about the interaction partner’s abilities, whereas confidence describes the belief that those abilities are actually sufficient to achieve a result in the specific situation.

Ability has high significance as the client has the expectation that the consultant brings in specific knowledge, skills and expertise to solve the client’s problem, to improve the organizational or processual conditions or to enable the client to achieve innovation in his business. The consultant’s abilities play thus an important role for the consulting outcome. The input of the consultant does not just refer to technical knowledge and experiences, but also to generic methods and skills (Kieser 1998). As a result the client’s perception of the consultant to be trustworthy is determined by the degree the consultant demonstrates that he possesses the required expert knowledge, problem solving competency, methodical skills and other abilities that are needed to support the consulting process and to (co-)produce the consulting outcome. In the consulting context, the perception of abilities is assumed to have higher weight in comparison to integrity and benevolence. Mayer et al. argue that benevolence and integrity by itself are insufficient to build the absolute fundament of trust, since a well-intentioned person who lacks in ability may not be considered as having the respective portion of trustworthiness (Mayer et al. 1995). The reliability of information about the consultant’s ability has particular relevancy in the early phases of the consulting project, when the client cannot yet refer to own meaningful experiences from the interactions with the consultant. At the beginning of the consulting process the consultant is therefore required to signal his actual abilities to enhance trustworthiness. Here, the reputation of the consulting organization is assumed to contribute to the client’s perception of ability-based trustworthiness, too. On the opposite side, abilities are also an essential influencing factor to evaluate the client’s trustworthiness by the consultant. The consultant is dependent on the functional expertise and knowledge of the client to ensure that the consulting outcome meets the specific requirements of client organization. As many consultants primarily focus on providing methodologies, it has particular relevance that the concretization to the client organization can be achieved, which requires the integration of the client’s expertise. It is assumed that the dependency on the client employee’s abilities is primarily relevant when the consultant acts in a coaching role focusing on the facilitation of the solution finding by the client.

As a next factor of trustworthiness, Mayer et al. subsumed several behavior-related attributes to the integrity dimension. Integrity is assumed when the trustor has the perception that the trustee adheres to a set of principles that the trustor finds acceptable, whereby both the adherence and the acceptability are important. It is referred to McFall (1987) who argued that an interaction partner could strictly follow one principle (e.g. strong focus on profit seeking), which however does not provide the perception of integrity to the trustor in that context as this principle is not acceptable for him. Besides this, integrity also encompasses virtues of reliability in terms of consistency of the party’s past actions, credible communication about the trustee from other parties, belief that the trustee has a strong sense of justice, and the extent to which the party’s actions are congruent with his or her words. For the evaluation of trustworthiness the perceived level of integrity matters instead of the reasons why the perception is formed (Mayer et al. 1995). The relevant set of principles that need to be adhered in the consulting context to demonstrate integrity are dominated by the client’s expectations that the consultant is striving to reach the goals of the consulting project, while he acts in professional manner and on behalf of the client’s interests. Vice versa, the consultant expects the client to give him the respective support to reach the goals and not to misuse the consulting engagement. Openness is considered to be an elementary driver for the perceived integrity in behavior why it can be seen as central component for personal trustworthiness (Brückerhoff 1982). For openness the consultant and client request a free flow of information in their relationship and that they do inform each other in complete manner. The significant impact of disclosure of information to the interpersonal trust development has been underlined by Morgan and Hunt (1994), while also Aulakh et al. (1996) have shown in their study that there is a significant positive correlation between the extent and quality of information exchange and the development of interpersonal trust. Interpersonal trust between the consultant and the client is therefore influenced by the client’s willingness to share the respective information in terms of organization-specific information, functional and industry-specific knowledge with the consultant that is needed to produce the consulting outcome (Das and Teng 1998; Lorbeer 2003).

Next to this, integrity is also demonstrated by honesty and truthfulness (Neubauer and Rosemann 2006; Kumar 2000; Lorbeer 2003). Both behavioral characteristics create a situation that the consultant and the client can rely on the given statements and provided information of the counterparty. Implicated honesty and truthfulness moreover give them essential orientation for acceptance of information, while the positive perception of those attributes is also seen as mechanism to reduce the uncertainty and complexity within the consulting process. Honesty of the interaction partner does also include the expectation of the client and the consultant to receive negative feedback if it is required (Seifert 2001). A further important dimension of integrity refers to the consistency of the consulting interaction partners with regard to his behavior. Based on consistent behavior the trustor can derive reliability and predictability out of it. This increases the perception of security and thus enhances the trustworthiness, as it will be interpreted as indicator for the future behavior of the interaction partner (Lewicki and Bunker 1996; Lorbeer 2003). The trustor hereby expects that his interaction partner will remain constant in what he has pronounced and presented as the prospect. If the client frequently changes his opinion about matters presented by the consultant for alignment or approval, this might lead to an increased demand for reconciliation with the client on the consultant side. On the other hand, consistency is also a strong requirement on the client side with a certain link to the consultant’s neutrality: The consultant appears as neutral when he is constant in his opinion and does not change it in discussions with different stakeholder of the client organization.

Benevolence is the third category for the perception of trustworthiness. It is characterized by Mayer et al. as “… the extent to which a trustee is believed to want to do good to the trustor, aside from an egocentric profit motive.” Benevolence therefore suggests that the trustee has some specific proximity to the trustor and there is a positive orientation to him. High benevolence of the potential trustee is thus, for example, inversely related to his motivation to lie. It basically captures virtues of altruism and loyalty (Mayer et al. 1995). Benevolence basically contributes to the development of interpersonal trust in the consultant-client relationship when it is assumed that the trustee has generally good motives and intentions for the other party in context to the consulting project as the social platform. Benevolent behavior requires that the client and the consultant in the role as trustee do not solely follow egocentric goals. Instead, they have a general favorable attitude towards the other. When the consultant wants to be attributed with benevolent characteristics it requires him to be aware of the interests and needs of the respective client employees. This is a prerequisite for the consultant that he can respect and take care of the client employees’ situation, and that he does not unconsciously carry out an action that is to the detriment of the client’s interest (Gambetta 1998). However, the sole knowledge of the client’s interests is not regarded to be sufficient. It is required that the consultant actively demonstrates concern about the prosperity of the client employees (Shaw 1997). Consultants can actively express the respective concern if they involve the client employees and incorporate their proposals and feedback, but also offer their direct and individual support. Overall, the client needs to have the perception that the consultant subordinates his own interests to the client’s interests. This is why the signaling of same-goal-orientation with the client is considered as essential. The client then senses emotional safety when he believes that even without being in steady contact with the consultant, his actions are basically aiming at common goals. At such a state, the client is also assumed to be ready to reduce his control demand over the consultant. Conversely, benevolent attributes are also relevant for the perceived trustworthiness of the client, as the consultant also has some face-saving and reputational interests. For a successful consulting outcome the consultant needs to have first and foremost a clear view of the real motives and goals of the consulting engagement. Clearly communicated motives and goals contribute positively to the trust generation. When the client demonstrates respect to the role of the consultant, he does not exploit him with abnormal task overloads and does not misuse him, then benevolent attributes of the client are acknowledged. This contributes to interpersonal trust building as fairness regarding the consultant’s engagement is signaled.

3.4 Situation-Specific Factors

Next to propensity to trust and the trustworthiness, the potential and actual degree of trust in a relationship is further driven by the situation-specific factors. Those furthermore moderate the influence of the other personal determinants, as Mayer et al. state that the context of the situation helps to determine the perceived level of trustworthiness (Mayer et al. 1995). To analyze the situation is therefore of critical relevance as trust is understood as social mechanism reflecting the constellation between the interaction partners. The consideration of situation-specific factors has a long tradition in the trust research. The initial fundament has been provided by Deutsch with his investigation in context of the Prisoner’s Dilemma studies and the examination of trust in those different situations for the interaction partners (Deutsch 1958, 1960). Mayer et al. further approach the situation-specific context with arguing that even though the level of trust determined by ability, benevolence, integrity and propensity may be constant, the specific consequences of trust will be determined by contextual factors. Those factors can refer to the stakes involved, the balance of power in the relationship, the perception of the level of risk and the alternatives available to the trustor. Perceived ability will change with the dynamics of the situation that requires that ability. A similar coherence is seen with regard to integrity that is also affected by the counterparty’s action. A decision of the counterparty may appear inconsistent with earlier decisions, why his integrity might be questioned when knowing nothing about the situation. The trustor’s perception and interpretation of the context affect both the need for trust and the evaluation of trustworthiness. Changes in such factors like the political climate and the perceived volition of the trustee in the situation can cause a reevaluation of trustworthiness. A basic situation-related facet is the level of risk. Risk itself is assumed to have impact on the trust building, as the propensity to trust decreases (ceteris paribus) with an increasing level of perceived risk in a situation. This bases on the fact that trust can only mediate subjective certainty to the trustee but does not create objective certainty to him. As risk is inherent in the behavioral manifestation, one does not need to risk anything in order to trust, however, one must take a risk in order to engage in a trusting action (Mayer et al. 1995).

The interpersonal trust development between the consultant and the client requires risk-taking. Such situation is characterized by a certain level of dependence of the consultant and the client on his counterparty. The level of risk determines the perceived vulnerability of the consultant or the client. The portion of risk of the participants of the consulting project varies in the course of the consulting process and dependents on the respective situations as well as is linked to the role of the consulting participant. In accordance to that, also the required level of interpersonal trust diversifies. The buyer of the consulting engagement who typically works on the executive or middle management level is usually the direct addressee of the consulting outcome. He bears a high business and organizational risk that the consulting outcome is an objectively and comprehensively elaborated result. Business-related dimensions dominate his risk spheres. Similar for the managing partner of the consultancy, since his main risk areas are seen in the violation of the overall relationship between the consulting and the client organization as well as the potential damage of the overall reputation of the consulting firm. Next to this, the consulting project leader and the client project leader are also seen to be highly dependent on the progress of the consulting process as there is usually high success-related personal attribution towards these roles. Participants of the consulting project on lower levels from the client organization (functional or processual experts, supporting personnel) as well as from the consulting organization (junior and senior consultants) are considered to have more individual-related risks in context of the consulting project, e.g. regarding their status in the client organization, allocated resources or the individual performance evaluation of the consultant.

In general, the weights of the three trustworthy dimensions ability, benevolence and integrity are assumed to vary in the course of the consulting process and also depend on the situation and the concerned personalities (Shaw 1997; Mayer et al. 1995; Seifert 2001). The higher the benevolent components of the trust relation between the consultant and the client are and the more direct experiences have been made between the interaction partners, the more robust is the portion of interpersonal trust. This leads to the situation that e.g. inconsistent behavior of the trustee would not necessarily result in a complete breach of the trust relation (Lewicki and Bunker 1996).

4 Practical Findings About Development of Interpersonal Trust in the Consultant-Client Relationship

At this stage the research matter of interpersonal trust development in the consulting process is enhanced by practical insights from expert interviews. The subsumption of the interviews is basically structured analogously to the conceptual trust model in the previous chapter with referring to the factors of trustworthiness in terms of ability, integrity and benevolence. As this investigation focuses on explanations and drivers that promote the interpersonal trust development specifically during consulting processes, the trustor’s propensity to trust as a dispositional facet of the individual was regarded as static attribute and has therefore not seen a separate consideration, but has been mentioned in the interviewee profiles below. Moreover, as shown in Sect. 3.4, situation-specific factors have influence on the significance of the various trustworthy attributes. This is why they were integrated and reflected in the respective sections of trustworthiness in that practical subsumptions.

For the selection of interviewees it was tried to consider different levels and roles of the consultants, the same as for different hierarchical levels of client employees involved in consulting processes. For instance, client employees acting in expert roles, as project manager or the “buyer”/“ordering client” were interviewed. On the opposite side, consultant interviewees with advanced career levels (senior consultant, consulting project manager) were selected, enhanced by a consultant acting as a freelancer. Next to this, also the required intensity of interactions between the consultant and the client varied in the consulting projects. The type of consulting projects the interviews based on are however quite homogeneous, as all projects relate to expert-oriented consulting concepts. Moreover, most consulting projects had an IT- and process-oriented thematic focus. Regarding the reference consulting projects of the interviews it needs to be highlighted that there is no integrated investigation of specific consulting projects from both the consultant and client side in parallel. Instead different projects were used as reference point for the consultant and client interviewees.

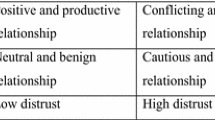

Tables 1 and 2 give an overview of the interviewee’s profiles selected for the roles as consultant or client:

4.1 General Significance of the Personal Level for Trust Building in the Consulting Project

In conjunction with the interviews conducted for this empirical investigation of interpersonal trust in the consultant-client relationship, also insights have been retrieved that indicate the general significance of the personal level between consultant and client for the trust building. Those relate to the overall significance of the research topic, and are therefore discussed in the following.

The interview with CLIENT-4 has indicated that person-related attributes do outcompete the brand of the consulting firm in building the trust relation between the consultant and the client. The client (a project manager of the client organization) stated that “ultimately, it doesn’t matter which brand the consultant is working for. Consulting is an absolute people business”. The consulting brand, however, could be helpful to signal reliance in the first instance, e.g. it could reduce a certain level of uncertainty in non-transparent markets. But the consulting brand is not considered to automatically create a credit of trust by the client at the beginning of the consulting project. CLIENT-1 confirmed this by stating that knowing from which consulting company the consultant comes from is not necessarily important for the creation of interpersonal trust towards this consultant. She further emphasized the importance of personal characteristics and personal abilities for the generation of interpersonal trust. The reputation of the consulting company is considered to be more relevant for inferring confidence into the abilities, particularly the knowledge of the consultancy, as stated by CLIENT-3. He (functional expert) further highlighted that for trust building in the consultant-client relationship human aspects are much more crucial. CONSULTANT-1 gave an important differentiation of the trust matter in context of the consultant-client relationship: He stated that the trust context “needs to be further distinguished between the trust on a personal level (e.g. honesty) and the competencies. One can say that one trusts an interaction partner’s abilities, but not him as a person”. CONSULTANT-1 moreover noted that the size and reputation of the consulting company have no essential effect on interpersonal trust building during the consulting process. Instead, he also highlighted the significance of personal characteristics, as “the client wants the personality. This relates to the character of the person. And it is also completely independent whether you come from a large or small consulting company”. This perspective is also shared by the other interviewed consultants, as CONSULTANT-2 has indicated that for trust it is important to have a personal relationship, and not only competency-related factors are crucial. Also in the interview with CONSULTANT-4 it has been noticed that trust development during the consulting process is seen personal-oriented and independent from the consulting organization’s reputation.

4.2 Trust Generation Through Reliance on Ability

With discussing how ability-related aspects are addressed in the interviews, the conceptual approach for this research work needs to be recapped: ability plays a role in the trust development in so far the trustor grants trust that the interaction partner made correct statements about his abilities or the information about his abilities are valid. As highlighted in Sect. 3.3, the question whether these abilities are actually sufficient to solve the existing problem rather refers to the matter of confidence. This problem of demarcation of trust from confidence to the abilities is exemplarily visible in the interview with CLIENT-1 (functional expert). She argued that it is positive for trust when the consultant is on the same competency level, and is therefore in the position to challenge the client. She furthermore honored the functional competency of the consultant, which would contribute to the quality of the consultant-client cooperation and argued that it is beneficial if she can also learn something from the consultants. Overall, she focused on the importance of the actual personal abilities to develop trust to the consultant. These statements need to be contrasted with the trust conception as stated above, and do therefore rather relate to the confidence in the abilities of the consultant.

As trust is assumed to be developed by relying on the information about the consultant’s abilities, a trusting relation can evolve when the consultant as interaction partner can confirm that he actually possesses the relevant abilities. This can be proved with successfully delivered working results by the consultant (CLIENT-4). The client’s uncertainty about the consultant’s abilities can also be compensated when the consultant demonstrates ability on a regular basis (CONSULTANT-2). Hereby, intensive interaction experiences between the consultant and the client are considered to promote the building of interpersonal trust (CONSULTANT-3). This experience-based trust resulting from good deliverables of the consultant reduces the control demand of the client over the consultant (CONSULTANT-4). Moreover, trust towards the consultant grows if the consultant constantly confirms that he has his work packages under control (CLIENT-2).

Comparing the results from this practical investigation with the conceptual outline in Sect. 3.3 it can be resumed that the matter of ability is particularly considered with the functional expertise of the consultant, as well as the ability to deliver good results. The last aspect indeed incorporates also other facets of the consultant’s abilities like methodological or social skills. Those, however, have not been addressed directly by the interviewees. The interviews pointed out that it is important to demonstrate the respective abilities on a regular basis in order to contribute to the interpersonal trust relation. However there were no findings that ability-related trustworthiness is specifically important at the early phases of a consulting project, as conceptually outlined in this work. Next to this, it can also be noted that the matter of ability is rather discussed with regard to the consultant. Even though in some case the interviewer tried to trigger the discussion about the relevancy of the client’s abilities during the consultant interviews, this has not been taken on much by the interviewed consultants why it can be reasoned that the client’s abilities do not play a significant role for the client’s trustworthiness.

4.3 Trust Generation Through Integrity

The interviews revealed several basic behavioral patterns of the interacting partners that promote an integrity-based trust building. Overall, CONSULTANT-2 mentioned basic integrity-related behavior of the client as very important to build up trust.

More specifically, honesty is considered to be one essential virtue for the interactions within the consulting project. CONSULTANT-1 stated that for building trust, one of the most important things is “to be open and honest”. When the consultant has a shortage in certain knowledge required for the consulting project, then it is important to reveal this in order to receive trust from the client. Also CONSULTANT-3 experienced that the client’s perception of a trustworthy consultant is promoted if he is honest in such a situation. If there is a knowledge gap on the consultant side that comes up in the interactions with the client employees, he considers it as “a legitimate process to request other consulting colleagues for that matter and to provide the client the respective response afterwards. This rather helps to develop trust on the client side, instead of giving the client a pseudo answer or an answer that is obviously wrong”. Moreover, honesty of the consultant to confirm his trustworthiness is also highly relevant when it comes to admitting failures that occurred on his side during the consulting process. However, admitting failures is also a critical topic for the consultants, as it would potentially discredit the consultant’s role in the consulting project. Therefore, admitting failures is a matter which consultants “as external service provider do usually deploy in dosed manner towards the client. Such things would rather not be expressed in written form, like in e-mails, but more (…) in personal conversations”. Next to this, there were hints in the interviews that also honesty on the client side promotes trust building by the consultant. Also here trust development is promoted when client employees are admitting failures (CONSULTANT-4). CONSULTANT-2 confirms this and states that “clearly, one has to say that honesty of the client is certainly the most important virtue to build up trust. But it is difficult to assess whether somebody is honest or not”. Interestingly, the matter of honesty is not a matter that has been brought up by the client employees during the interviews. Apparently, the honesty of the consultant is considered to be a virtue that should be taken for granted. Exemplarily, CLIENT-2 immediately led over to other specific aspects when the discussion of consultant’s honesty was intended.

Further important findings in the interviews that refer to integrity-related facets of trustworthiness can be categorized as transparency and openness. CLIENT-1 indicated that the consultant has to ensure traceability in his working to promote his trustworthiness. Signaling transparency to the client is also highly valued by CONSULTANT-1. “When he recognizes that the client is uncertain then the consultant has to try to involve the client as much as possible into the consulting work.” It can also help to “provide the client with daily status updates” about the work of the consultant and to answer his questions in detail to reduce his uncertainty”. CONSULTANT-1 further resumes that it is one of the most important virtues to be open. CLIENT-3 also highlights that it is critical that the consultant makes transparent what his goals and motives are. This should confirm the client that the consultant does not have a “hidden agenda”. He furthermore underlined the importance of openness and transparency of the consultant to provide certainty to the client, as it has great significance for the client to know “that the consultant is not going in the wrong direction, since he is naturally lacking certain specific processual knowledge of the client organization”. CONSULTANT-3 also considers this aspect as vital for maintaining a trust relation to the client, as it is required to “steadily show open and direct communication to the client”, also with regard to possible failures made on the consultant side. CLIENT-3 emphasized that openness of the consultant towards the client organization is required in several respects. Hereby, a trusting consultant should be ready for open discussion with the client about ideas and proposals. Additionally, he underlined that consultant’s openness also means that he takes the opinions of the client employees into consideration. He refers to a concrete personal project experience in which “the consultant has refused to take the opinions of functional departments of the client organization into consideration. Moreover, this consultant declined to accept the decisions of the clients based on further information”. This led to non-acceptance of the consultant and trust problems. It is therefore of critical importance for the consultant to adopt the feedback of the client organization to maintain the trust relation to them.

In the same line, openness and transparency are also perceived as important virtues for the trustworthiness of the client employees. CONSULTANT-4 hereby said that trust development is promoted when client employees also reveal background information and direct feedback to the consultant. “When the client employees admit that there are specific problems on their side, and if they tell you things that shouldn’t actually be told, then this is seen as clear indication that client employees try to build up a trusting relation to the consultant”. In that context the trustworthiness of the client employees is also enhanced when they show directness towards the consultant. Hereby CONSULTANT-3 stated that “to straightforward people on the client side that are open about their opinions and the consultant knows what their attitude is, it is more likely to build-up trust”. As an opposite, it is perceived to be negative when the client uses devious tactics and does not allow the consultant to gain full insight into the relevant set of information. Next to this, further trustworthy attributes are recognized in the interview with CLIENT-3. For him it is very important that the consultant shows authentic behavior during the consulting project. He further states that the consultant is required to assume a neutral position within the client organization during the consulting process.

When contrasting the practical findings of integrity-based trustworthiness with the conceptual outline done in Sect. 3.3 it turns out that the interview results basically suggest very similar dimensions for integrity-based trust development. In that regard, particularly the attributes of openness, honesty and truthfulness have been stated, whereas there were no hints regarding the relevancy of consistent behavior of the consultant. Honesty was highlighted as an important attribute for the consultant’s trustworthiness specifically from the consultant interviewees, whereas there was interestingly no respective emphasize from the client interviewees. It is assumed that the consultant’s honesty is rather taken as granted by the client when engaging a professional service. The interviews also pointed out that honesty in the consulting project is getting crucial when failures made during the project have to be admitted. Moreover there was also further concretization provided regarding openness, as next to the stated client’s request of direct involvement and participation into the consulting project, it has been highlighted that transparency of the consultant’s approach and work steps is crucial for building interpersonal trust. This requires the consultant to go in regular alignment with the client, which in turn gives the client inner security about the consultant.

4.4 Trust Generation Through Benevolence

With conducting the interviews, also benevolence-related factors for determining the trustworthiness were revealed. CLIENT-4 stated that a trusting client is “somebody with whom he gets along also on a personal level and with whom he talks the same language”. This also indicates that consulting is seen foremost as a “people-business”. CLIENT-1 also refers to the importance of benevolence in the consultant-client relationship and considers a good communication between them as indication for that. CONSULTANT-2 emphasized that trust to the consultant is also to a great part a matter of sympathy, which is also expressed by the extent of personal communication. “An individual unconsciously trusts a likeable person more than a non-likeable person... why sympathy plays an important role”. The matter of sympathy has also been underlined by CONSULTANT-3 in that regard. Furthermore, CONSULTANT-3 also highlighted that when doing a client a favor this also promotes the perception of benevolence-related trustworthiness. Finally, it has also been indicated by CONSULTANT-4 that a trust offer with proactively demonstrating trust can also have positive effect on the trustworthiness of this interaction partner.

Moreover, the interviews have also revealed that benevolence of the consultant is also by a large extent expressed through the perception of the same-goal-orientation between the consultant and the client. The client needs to get the feeling that the consultant follows the same goals and motives (CLIENT-3). The consultant has to demonstrate that he is on the same side (CONSULTANT-1). The consultant, therefore, needs to show proactivity and to demonstrate that he thinks with the client. “If the consultant thinks outside the box, he thinks with the other and acts with foresight, then this is enormously helpful for building trust to the consultant” (CLIENT-4). It is also honored when “the consultant questions certain things and also raises criticism against the client” (CLIENT-1). To demonstrate benevolence by the consultant, “it is better to show definiteness instead of being reserved and not provoking potential annoyance”. The interviewee moreover highlighted that a trust-based cooperation requires the feeling that the consultant represents the same views (CLIENT-1). CLIENT-2 (project manager in the client organization) has also stated that trust towards the consultant is promoted if the consultant demonstrates that he is thinking the same way as the client, and gives hints to the client about improvement potentials on his own initiative. Trust is particularly promoted if the consultant “pro-actively gives statements on existing problems, provides recommendations, thinks as oneself and has not solely his own business interests in focus” (CLIENT-2). For a consultant to be able to support the goals and motives of the individual client employees, it is also required to discover the interests and the political positions of the client employees to initiate the trust building (CONSULTANT-1). It was also mentioned that the aspect of benevolence could particularly be demonstrated when the consultant gives support to the client in extraordinary situations. This promotes the feeling of solidarity on the client side, exemplarily when the consultant offers extra working hours to help the client in solving an individual critical issue (CLIENT-4).

During the interviews further findings for benevolence regarding the hierarchical status of individuals were made. Hereby CONSULTANT-2 stated that client employees with a high hierarchical level are considered to be less trustworthy compared to client employees acting in expert roles. Moreover, CONSULTANT-4 indicated that young client employees with high claim for career development are assumed to have generally lower trustworthiness for the consultant, as they frequently show opportunistic behavior. Conversely, trust building towards consultants is also seen in dependence to their roles and levels; (Senior) Managers are assumed to be primarily business-driven, what decreases their general level of benevolence and trustworthiness. In that regard, freelancing consultants are assumed to be less career-oriented, thus this increases their trustworthiness.

Comparing the practical findings with the conceptual outline in Sect. 3.3 it can be subsumed that those go into the same direction for determining benevolence-related trustworthiness. The facets of loyalty and altruism are pointed out also in the interviews. Thus, the interviews highlighted the importance of same-goal-orientation and direct personal support to develop trust. It has been shown that a trust offer given by one party is often a fruitful step into a mutual trusting relationship between the consultant and the client. It has been revealed that the quality of communication between the consultant and the client is a good indicator of how much benevolence-driven trust is given. Otherwise, there were no direct hints about the importance of fairness for the trust building, e.g. with regard to avoidance of consultant’s misuse in the client organization. Additional insights have been provided concerning the relevancy of the hierarchical level for the trust relations in the consulting context.

5 Concluding Remarks on Research

This research work has investigated the factors for interpersonal trust development with referring to the conceptual model of Mayer et al. as well as subsuming practical findings from expert interviews. The latter followed an open explorative approach to identify generic explanations for trust building between the consultant and the client based on the interviewee’s overall experience. Future research should aim for concretizing the results further through integrated case studies that comprise several participants of a certain consulting project in order to reflect the specific project context on both the consultant and client in parallel. The investigation is to be deepened with observing the various attributes of trustworthiness in the complete course of the consulting process. Here, also the individual’s propensity to trust as a dispositional facet as well as the situation-related aspects like risk positions are to be captured to further derive findings in the respective trust environments. Moreover, those dynamic observations will also provide further explanation about the influence and weighting of the trustworthiness attributes in the course of the consulting project. A limitation of practical research findings of this work is seen in the relatively low number of interview partners as well as in the selection of consulting projects, which mainly referred to expert-oriented consulting engagements. Consecutive research work should also integrate the practical investigation of coaching roles or consulting projects focusing on organizational development.

References

Aulakh PS, Kotabe M, Sahay A (1996) Trust and performance in cross-border marketing partnerships: a behavioral approach. J Int Bus Stud 27(5):1005–1032

Barchewitz C, Armbrüster T (2004) Unternehmensberatung. Marktmechanismen, Marketing, Auftragsakquisition. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden

Brückerhoff A (1982) Vertrauen. Versuch einer phänomenologisch-idiographischen Näherung an ein Konstrukt. Dissertation, University Münster

Castaldo S (2002) Meanings of trust: a meta-analysis of trust definitions. Working paper presented at 2nd conference of the European Academy of Management (EURAM), Stockholm, Sweden, 09–11 May 2002

Coers J, Heinecke J (2002) Die Steuerungsarchitektur in Beratungsprozessen – Kooperationsprozesse von Beratern und Klienten. In: Mohe M, Heinecke J, Pfriem R (eds) Consulting – Problemlösung als Geschäftsmodell. Theorie, Praxis, Markt. Klett-Cotta Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 195–218

Covin TJ, Fisher TV (1991) Consultant and client must work together. J Manag Consult 6(4):11–19

Das TK, Teng BS (1998) Between trust and control: developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Acad Manag Rev 23(3):491–512

Dean DR (2005) Arbeiten mit Managementberatern: Bausteine für eine erfolgreiche Zusammenarbeit. In: Petmecky A, Deelmann T (eds) Arbeiten mit Managementberatern: Bausteine für eine erfolgreiche Zusammenarbeit. Springer, Berlin, pp 13–17

Deutsch M (1958) Trust and suspicion. J Confl Resolut 2(1):265–279

Deutsch M (1960) The effect of motivational orientation upon trust and suspicion. Hum Relat 13(1):123–139

Deutsch M (1962) Cooperation and trust: some theoretical notes. In: Jones MR (ed) Nebraska symposium on motivation, Lincoln, pp 275–319

Gambetta D (1998) Can we trust? Making and breaking cooperative relations. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Gillespie N (2003) Measuring trust in working relationships: the behavioral trust inventory. Working paper presented at annual meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle, USA, 01–06 Aug 2003

Glückler J, Armbrüster T (2003) Bridging uncertainty in management consulting: the mechanisms of trust and networked reputation. Organ Stud 24(2):269–297

Greschuchna L (2006) Vertrauen in der Unternehmensberatung: Einflussfaktoren und Konsequenzen. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden

Höner D (2008) Die Legitimität von Unternehmensberatung: Zur Professionalisierung und Institutionalisierung der Beratungsbranche. Metropolis, Marburg

Jacobsen H (2005) Der Kunde in der Dienstleistungsbeziehung. Beiträge zur Soziologie der Dienstleistung. Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden

Jehle R (2001) Aufbau und Absicherung von Vertrauenspotentialen durch Kommunikationspolitik: Instrumente, deren Anwendung und Relevanz im Marketing klein- und mittelständischer Investitionsgüterhersteller. Lang, Frankfurt am Main

Jeschke K (2004) Marketingmanagement der Beratungsunternehmung. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden

Kieser A (1998) Immer mehr Geld für Unternehmensberatung – und wofür? Organisationsentwicklung 17(2):62–69

Kilduff M (2006) Editor’s comments: prize-winning articles for 2005 and the first two decades of AMR. Acad Manag Rev 31(4):792–793

Klaus E (2002) Vertrauen in Unternehmensnetzwerken: eine interdisziplinäre analyse. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden

Kralj D (2004) Vergütung von Beratungsdienstleistungen: Agencytheoretische und empirische Analyse. Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden

Kumar N (2000) The power of trust in manufacturer-retailer relationships. Harv Bus Rev 74(6):92–106

Lane C (1998) Theories and issues in the study of trust. In: Lane C, Bachmann R (eds) Trust within and between organizations: conceptual issues and empirical applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 1–30

Lewicki RJ, Bunker B (1996) Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In: Kramer R, Tyler T (eds) Trust in organizations. Sage, Newbury Park, pp 114–139

Lorbeer A (2003) Vertrauensbildung in Kundenbeziehungen. Ansatzpunkte zum Kundenbindungsmanagement, Deutscher Universitätsverlag, Wiesbaden

Luhmann N (1979) Trust and power. Wiley, New York

Luhmann N (1988) Familiarity, confidence, trust: problems and alternatives. In: Gambetta D (ed) Trust: making and breaking of cooperative relations. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 94–107

Luhmann N (1989) Vertrauen: Ein Mechanismus der Reduktion sozialer Komplexität, 3rd edn. Enke, Stuttgart

Maister DH, Green CH, Galford RM (2000) The trusted advisor. Simon & Schuster, London

Maleri R (1997) Grundlagen der Dienstleistungsproduktion. Springer, Berlin