Abstract

Psychologists claim that narcissists have inflated, exaggerated, or excessive self-esteem. Media reports state that narcissists suffer from self-esteem on steroids. The conclusion seems obvious: Narcissists have too much self-esteem. A growing body of research shows, however, that narcissism and self-esteem are only weakly related. What, then, separates narcissism from self-esteem? We argue that narcissism and self-esteem are rooted in distinct core beliefs—beliefs about the nature of the self, of others, and of the relationship between the self and others. These beliefs arise early in development, are cultivated by distinct socialization practices, and create unique behavioral patterns. Emerging experimental research shows that these beliefs can be changed through precise intervention, leading to changes at the level of narcissism and self-esteem. An important task for future research will be to develop interventions that simultaneously lower narcissism and raise self-esteem from an early age.

The writing of this article was supported by funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 705217 to Eddie Brummelman and a research priority area YIELD graduate program grant No. 022.006.013 to Çisem Gürel and Eddie Brummelman.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Around the time of grammar school I had this incredible desire to be recognized. […] I got the feeling that I was meant to be more than just an average guy running around, that I was chosen to do something special. At that point, I didn’t think about money. I thought about the fame, about just being the greatest. I was dreaming about being some dictator of a country or some savior like Jesus. Just to be recognized.

—Arnold Schwarzenegger, in an interview with Rolling Stone (Peck, 1976)Footnote 1

As a young adolescent, Arnold Schwarzenegger was already thinking like a narcissist. He saw himself as a superior being, while seeing others as “average guy[s] running around.” Yet, despite looking down on others, he still depended on them to achieve what he valued above all else: recognition . In fact, he used his social relationships as a means to achieve recognition. And it did not matter how he achieved it—whether by being a dictator or a savior. As we know now, he ended up as bodybuilder, actor, and politician, all professions that allowed him to wallow in the limelight.

But did Arnold Schwarzenegger have high self-esteem ? Despite his clearly narcissistic self-views, nowhere did he mention that he was happy with the person he was or that he considered himself worthy or valuable. This is surprising, given that conventional wisdom tells us that narcissism is a form of high self-esteem. In this chapter, we argue that narcissism and self-esteem are two distinct dimensions of the self. We focus on prototypical, grandiose narcissism, rather than on its vulnerable counterpart (Cain, Pincus, & Ansell, 2008; Miller et al., 2011). We suggest that recognizing the line that runs through narcissism and self-esteem is key to scholarly efforts toward helping people develop healthy views of themselves.

Conventional Wisdom

People intuitively infer that narcissism and self-esteem are intimately linked. In his essay On Narcissism, Freud (1914/1957) wrote that “self-regard appears to us to be an expression of the size of the ego” (p. 98). Today, the American Heritage Dictionary defines narcissism as “excessive […] admiration of oneself,” and self-esteem as “pride in oneself.” This definition suggests that narcissism simply represents an excess of self-esteem—taking too much pride in oneself. This belief exists among experts and laypersons alike. Psychologists, including ourselves, have defined narcissism as a form of “excessive self-esteem,” “inflated self-esteem,” “exaggerated self-esteem,” “unwarranted self-esteem,” or “defensive high self-esteem.” Similarly, media reports have labeled narcissism as “self-esteem on steroids” or “blown-up self-esteem.” The conclusion seems obvious: Narcissists like themselves a little too much.

However, narcissism and self-esteem might be much more distinct than conventional wisdom has led people to believe (Brummelman, Thomaes, & Sedikides, 2016). If narcissism really is an inflated form of self-esteem, narcissism and self-esteem should correlate strongly, and there should be no narcissists with low self-esteem. However, the correlation between narcissism and self-esteem is only weak or modest (Campbell, Rudich, & Sedikides, 2002; Thomaes & Brummelman, 2016) and becomes even weaker when researchers use more valid measures of narcissism and self-esteem (Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2004) and when they encourage narcissists to report their self-esteem truthfully (Myers & Zeigler-Hill, 2012). Moreover, latent class analysis shows that there are narcissists with low self-esteem; in fact, there are about as many narcissists with low self-esteem as there are narcissists with high self-esteem (Nelemans et al., 2017).

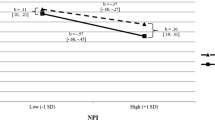

A Social-Cognitive Perspective

These findings beg the question: What separates narcissism from self-esteem? We approach this question from a social-cognitive perspective (Brummelman, 2017; Olson & Dweck, 2008). Rather than describing the stable patterns of behavior that characterize narcissism and self-esteem, we identify underlying core beliefs of narcissists and people with high self-esteem (hereafter: high self-esteemers). These beliefs concern the nature of the self, of others, and of the relationship between the self and others (Fig. 5.1). Such beliefs can create stable behavioral patterns by shaping what goals people pursue and by guiding how people perceive, select, modify, and respond to their environments.

Beliefs About the Self

Narcissists believe they are inherently superior to their fellow humans. When Ernest Jones (1913/1951) described narcissism as a personality trait , he labeled it the God Complex, echoing narcissists’ belief in their own greatness. Narcissists see themselves as superior on agentic traits such as competence and intelligence, but not on communal traits such as warmth and kindness (Campbell et al., 2002). In addition, they hold exalted views of themselves even if such views conflict with reality (Grijalva & Zhang, 2016). For example, narcissists think they are superb leaders when they hinder group performance (Nevicka, Ten Velden, De Hoogh, & Van Vianen, 2011); they believe they are interpersonally attractive when others do not think so (Gabriel, Critelli, & Ee, 1994); and they see themselves as geniuses when their IQ scores are not on par (Paulhus, Harms, Bruce, & Lysy, 2003).

By contrast, high self-esteemers believe they are worthy, but do not consider themselves superior to others. As Morris Rosenberg (1965) wrote, “When we deal with self-esteem, we are asking whether the individual considers himself adequate—a person of worth—not whether he considers himself superior to others” (p. 62). Whereas narcissists primarily value their agentic traits, high self-esteemers value both their agentic and their communal traits (Campbell et al., 2002). And while narcissists close their eyes to reality, high self-esteemers’ views of themselves are more grounded in reality (Gabriel et al., 1994).

Beliefs About Others

Unsurprising given their sense of superiority, narcissists look down on others. Not only do they believe that others are subservient to them (Park & Colvin, 2015), they sometimes even dehumanize others (Locke, 2009). Yet, at the same time, narcissists covet others’ admiration. Roseanne Barr expressed this sentiment in an interview with Gear Magazine: “I hate every human being on earth,” she said, “I feel that everyone is beneath me, and I feel they should all worship me” (Guccione, 2000). According to some researchers, narcissists are addicted to admiration: They crave admiration, are tolerant to its effects, and experience withdrawal symptoms when it is withheld (Baumeister & Vohs, 2001; Thomaes & Brummelman, 2016). To elicit admiration, narcissists strive to stand out and get ahead (Wallace & Baumeister, 2002), even in settings where such behavior is inappropriate (Sedikides, Campbell, Reeder, Elliot, & Gregg, 2002). For example, even in their close relationships, narcissists attempt to dominate others, surpass others, and ridicule others (Campbell, Foster, & Finkel, 2002; Keller et al., 2014).

To a great degree, narcissists base their sense of worth on others’ admiration for them. When they are admired, they feel on top of the world; but when they are not, they feel like sinking into the ground (Brummelman, Nikolić, & Bögels, 2018; Tracy, Cheng, Robins, & Trzesniewski, 2009). Narcissists often externalize these feelings of shame by lashing out angrily or aggressively against others (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998; Thomaes, Bushman, Stegge, & Olthof, 2008; Thomaes, Stegge, Olthof, Bushman, & Nezlek, 2011). This process, known as humiliated fury or the shame-rage cycle, can escalate into acts of violence; for example, case studies suggest that narcissism puts youth at risk for school shootings (Verlinden, Hersen, & Thomas, 2000).

In contrast, high self-esteemers do not look down on others or dehumanize others (Locke, 2009; Park & Colvin, 2015); they believe that others have intrinsic worth and do not see others as a means to obtain admiration. Even if they are rejected by others, high self-esteemers are unlikely to feel ashamed or to lash out; rather, they tend to forgive others and seek reconciliation with them (Eaton, Ward Struthers, & Santelli, 2006; Murray, Rose, Bellavia, Holmes, & Kusche, 2002).

Beliefs About Relationships

Narcissists believe that their relationships follow a zero-sum principle: Only one of us can be the best, so your failure is my success, and my success is your failure (Brummelman et al., 2016). Narcissists desire to get ahead rather than get along (Thomaes, Stegge, Bushman, Olthof, & Denissen, 2008), even in interdependent settings. When they collaborate with others, narcissists praise themselves for successes, blame their partners for failures (Campbell, Reeder, Sedikides, & Elliot, 2000), and attempt to secure short-term benefits for themselves, at the expense of their partners and the common good (Campbell, Bush, Brunell, & Shelton, 2005). Unsurprisingly, this puts a strain on their relationships: Narcissists’ charming first impressions crumble with the passage of time (Leckelt, Küfner, Nestler, & Back, 2015; Paulhus, 1998).

In sharp contrast, high self-esteemers believe that their relationships follow a non-zero-sum principle : We can both be worthy, so we can both get what we want (Crocker, Canevello, & Lewis, 2017). High self-esteemers desire to get along rather than get ahead (Thomaes et al., 2008). Thus, they are likely to care for others, share with others, and help others in their goal pursuits (Zuffianò et al., 2016). This benefits their relationships: High self-esteemers are well-liked by others, even in the long run (De Bruyn & Van Den Boom, 2005; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000).

Research Priorities

Whereas much existing research describes the stable patterns of behavior that characterize narcissism and self-esteem, we attempted to uncover the core beliefs that give rise to those behavioral patterns. Our social-cognitive approach builds on classic theories of personality that feature beliefs, such as cognitive-affective encodings (Mischel & Shoda, 1995), basic beliefs (Epstein, 2003), implicit theories (Dweck & Leggett, 1988), working models (Bowlby, 1969), schemas (Young, 1994), personal myths (McAdams, 1993), and personal constructs (Kelly, 1955). Core beliefs can be defined precisely, measured directly, and changed effectively. Our approach thus enables researchers to peer under the surface of narcissism and self-esteem: to trace their origins, understand their stability , and explore their malleability.

Origins

One issue is where narcissism and self-esteem come from. Both emerge around the age of 7 (Thomaes & Brummelman, 2016), when children begin to make global self-evaluations (e.g., “I am great!”) and to use social-comparison information for the purpose of self-evaluation (e.g., “I am better than others!”).

Although partly genetic (Neiss, Sedikides, & Stevenson, 2002; Vernon, Villani, Vickers, & Harris, 2008), narcissism and self-esteem are shaped by the social environment. Longitudinal research has revealed that they arise from distinct socialization experiences in childhood (Brummelman et al., 2015; Brummelman, Nelemans, Thomaes, & Orobio de Castro, 2017; also see Harris et al., 2017). Narcissism is nurtured, at least in part, by parental overvaluation—how much parents see their own child as extraordinary and entitled. Overvaluing parents overestimate, overclaim, and overpraise their child’s qualities, while helping the child stand out, for example, by giving him or her an uncommon first name (Brummelman, Thomaes, Nelemans, Orobio de Castro, & Bushman, 2015). From these experiences, children infer that they are superior, the core belief underlying narcissism. By contrast, self-esteem is nurtured, at least in part, by parental warmth —how much parents treat their child with affection and appreciation. Warm parents value their child’s company, share joy with the child, and show interest in the child’s activities (Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Rohner, 2004). From these experiences, children infer that they are worthy, the core belief underlying self-esteem.

The research agenda should deepen our understanding of these socialization processes. What are the precise behavioral manifestations of parental overvaluation and warmth? What inferences do children make based on those manifestations? And how do these inferences come to bear on new situations? Researchers should also study socialization influences outside of the family context. Especially when children transition into adolescence, peers begin to assume the role of socializing agents (Crone & Dahl, 2012; Harter, 2012). How are narcissism and self-esteem shaped by experiences within the peer group?

Stability

Another issue is how narcissism and self-esteem change over the course of life . Despite emerging at the same age, they have remarkably distinct developmental trajectories. While narcissism peaks in adolescence and then gradually falls throughout life (Carlson & Gjerde, 2009; Foster, Keith Campbell, & Twenge, 2003), self-esteem drops in adolescence and then gradually rises throughout life (Robins, Trzesniewski, Tracy, Gosling, & Potter, 2002). Still, individual differences in narcissism and self-esteem are remarkably stable (Carlson & Gjerde, 2009; Frick, Kimonis, Dandreaux, & Farell, 2003; Trzesniewski, Brent, & Robins, 2003).

Why are these individual differences so stable? There might be several reasons (Caspi & Roberts, 2001). One is that narcissists and high self-esteemers perceive, select, modify, and respond to situations in ways that maintain or even exacerbate their traits over time. For example, narcissists may select settings with a clear hierarchy, such as corporations that enable them to rise through the ranks (Zitek & Jordan, 2016). They may compete with others to reach the top (Roberts, Woodman, & Sedikides, 2017). As they move to increasingly responsible positions, they may come to perceive themselves as even more special and entitled, which fuels their narcissism levels (Piff, 2014). Unlike narcissists, high self-esteemers may select settings in which people are treated as equals. They may collaborate with others to advance the collective, while building relationships with them (Campbell et al., 2005; Crocker et al., 2017). As they work with others and feel socially valued, they may perceive themselves as even more useful and needed, which fuels their self-esteem levels (Leary & Baumeister, 2000). Thus, narcissism and self-esteem may not be set in stone (i.e., inborn, deeply ingrained, impossible to change) but rather be maintained through self-sustaining transactions between the person and the environment (also see Crocker & Brummelman, in press). Studying these transactions will shed light on the processes that drive continuity and change in personality more broadly.

Malleability

Can narcissism and self-esteem be changed? Although scholars agree that self-esteem can be changed (O’Mara, Marsh, Craven, & Debus, 2006), they are more skeptical about changing narcissism, and with good reason. When left untouched, narcissism is remarkably stable (Frick et al., 2003). Narcissists might be unwilling to change, because they see their narcissistic traits as strengths rather than as weaknesses (Carlson, 2013) and they readily blame their problems on others rather than on themselves (Thomaes et al., 2011). Even if they try to change, they do so halfheartedly; for example, they quit therapy prematurely (Ellison, Levy, Cain, Ansell, & Pincus, 2013).

Nevertheless, our social-cognitive approach suggests that narcissism can be changed if interventions target pointedly its underlying core beliefs (Brummelman et al., 2016). A promising development in psychology is the emergence of brief, psychologically precise interventions that change people’s core beliefs (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Walton, 2014). Because these interventions are stealthy (i.e., consisting of brief exercises that do not convey to recipients that they are in need of help), they may circumvent narcissists ’ resistance against change (Brummelman & Walton, 2015). Emerging research illustrates this. For example, inviting people to think about what makes them similar to others or connected with others reduces their narcissism levels (Giacomin & Jordan, 2014; Piff, 2014), curtails their narcissistic aggression (Konrath, Bushman, & Campbell, 2006), and improves their relationship functioning (Finkel, Campbell, Buffardi, Kumashiro, & Rusbult, 2009). Similarly, helping low self-esteemers reconstrue their social relationships so that they feel more included and valued raises their self-esteem levels and improves their relationship functioning over time (Marigold, Holmes, & Ross, 2007, 2010). Thus, changes in core beliefs may lead to changes in personality (Dweck, 2008). Researchers should develop such interventions , test them through rigorous field experiments, and explore how their effects can be sustained over time.

Conclusion

As we have shown, narcissism and self-esteem are underpinned by distinct core beliefs: beliefs concerning the nature of the self, of others, and of the relationship between the self and others. Although these beliefs arise early in development and generate stable patterns of behavior, they can be changed effectively through precise intervention . Thus, recognizing the line that runs through narcissism and self-esteem can help researchers develop interventions that nurture healthy self-views from an early age onward.

Notes

- 1.

Even when we describe individuals, we would not and could not diagnose them as “narcissists.” Our chapter focuses on narcissism as an everyday, subclinical personality trait, not as a personality disorder.

References

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Narcissism as addiction to esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 206–210.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Brown, R. P., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2004). Narcissism and the non-equivalence of self-esteem measures: A matter of dominance? Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 585–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2003.11.002

Brummelman, E., Thomaes, S., Nelemans, S. A., Orobio de Castro, B., Overbeek, G., & Bushman, B. J. (2015). Origins of narcissism in children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 112, 3659–3662. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1420870112

Brummelman, E., Thomaes, S., Nelemans, S. A., Orobio de Castro, B., & Bushman, B. J. (2015). My child is God’s gift to humanity: Development and validation of the Parental Overvaluation Scale (POS). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 665–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000012

Brummelman, E., & Walton, G. M. (2015). “If you want to understand something, try to change it”: Social-psychological interventions to cultivate resilience. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, 24–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X14001472

Brummelman, E., Thomaes, S., & Sedikides, C. (2016). Separating narcissism from self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25, 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721415619737

Brummelman, E., Nelemans, S. A., Thomaes, S., & Orobio de Castro, B. (2017). When parents’ praise inflates, children’s self-esteem deflates. Child Development, 88, 1799–1809. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12936

Brummelman, E. (2017). The emergence of narcissism and self-esteem: A social-cognitive approach. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2017.1419953

Brummelman, E., Nikolić, M., & Bögels, S. M. (2018). What’s in a blush? Physiological blushing reveals narcissistic children’s social-evaluative concerns. Psychophysiology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13201

Bushman, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.219

Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006

Campbell, W. K., Bush, C. P., Brunell, A. B., & Shelton, J. (2005). Understanding the social costs of narcissism: The case of the tragedy of the commons. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1358–1368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205274855

Campbell, W. K., Foster, C. A., & Finkel, E. J. (2002). Does self-love lead to love for others?: A story of narcissistic game playing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.340

Campbell, W. K., Reeder, G. D., Sedikides, C., & Elliot, A. J. (2000). Narcissism and comparative self-enhancement strategies. Journal of Research in Personality, 34, 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2000.2282

Campbell, W. K., Rudich, E. A., & Sedikides, C. (2002). Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202286007

Carlson, E. N. (2013). Honestly arrogant or simply misunderstood? Narcissists’ awareness of their narcissism. Self and Identity, 12, 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2012.659427

Carlson, K. S., & Gjerde, P. F. (2009). Preschool personality antecedents of narcissism in adolescence and young adulthood: A 20-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 570–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.03.003

Caspi, A., & Roberts, B. W. (2001). Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1202_01

Cohen, G. L., & Sherman, D. K. (2014). The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 333–371. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137

Crocker, J., & Brummelman, E. (in press). The self: Dynamics of persons and their situations. In K. Deaux & M. Snyder (Eds.), Handbook of personality and social psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Crocker, J., Canevello, A., & Lewis, K. A. (2017). Romantic relationships in the ecosystem: Compassionate goals, nonzero-sum beliefs, and change in relationship quality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000076

Crone, E. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13, 636–650. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3313

Davidov, M., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development, 77, 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00855.x

De Bruyn, E. H., & Van Den Boom, D. C. (2005). Interpersonal behavior, peer popularity, and self-esteem in early adolescence. Social Development, 14, 555–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00317.x

Dweck, C. S. (2008). Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 391–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00612.x

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Eaton, J., Ward Struthers, C., & Santelli, A. G. (2006). Dispositional and state forgiveness: The role of self-esteem, need for structure, and narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.02.005

Ellison, W. D., Levy, K. N., Cain, N. M., Ansell, E. B., & Pincus, A. L. (2013). The impact of pathological narcissism on psychotherapy utilization, initial symptom severity, and early-treatment symptom change: A naturalistic investigation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95, 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.742904

Epstein, S. (2003). Cognitive-experiential self-theory of personality. In T. Millon & M. J. Lerner (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychology, volume 5: Personality and social psychology (pp. 159–184). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Finkel, E. J., Campbell, W. K., Buffardi, L. E., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. E. (2009). The metamorphosis of Narcissus: Communal activation promotes relationship commitment among narcissists. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1271–1284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209340904

Foster, J. D., Keith Campbell, W., & Twenge, J. M. (2003). Individual differences in narcissism: Inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 469–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00026-6

Freud, S. (1957). On narcissism: An introduction. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 69–102). London: Hogarth Press (Original work published 1914).

Frick, P. J., Kimonis, E. R., Dandreaux, D. M., & Farell, J. M. (2003). The 4 year stability of psychopathic traits in non-referred youth. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 21, 713–736. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.568

Gabriel, M. T., Critelli, J. W., & Ee, J. S. (1994). Narcissistic illusions in self-evaluations of intelligence and attractiveness. Journal of Personality, 62, 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00798.x

Giacomin, M., & Jordan, C. H. (2014). Down-regulating narcissistic tendencies: Communal focus reduces state narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 488–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213516635

Grijalva, E., & Zhang, L. (2016). Narcissism and self-insight: A review and meta-analysis of narcissists’ self-enhancement tendencies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42, 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215611636

Guccione, B. J. (2000, October). Roseanne bares all. Gear Magazine.

Harris, M. A., Donnellan, M. B., Guo, J., McAdams, D. P., Garnier-Villareal, M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2017). Parental co-construction of 5-13-year-olds’ global self-esteem through reminiscing about past events. Child Development, 88, 1810–1822. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12944

Harter, S. (2012). The construction of the self: Developmental and sociocultural foundations. New York: Guilford Press.

Jones, E. (1951). The God Complex. In E. Jones (Ed.), Essays in applied psychoanalysis: Essays in folklore, anthropology and religion (Vol. 2, pp. 244–265). London: Hogarth Press (Original work published 1913).

Keller, P. S., Blincoe, S., Gilbert, L. R., Dewall, C. N., Haak, E. A., & Widiger, T. (2014). Narcissism in romantic relationships: A dyadic perspective. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33, 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2014.33.1.25

Kelly, G. A. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs, Vol. 1. A theory of personality. New York: Norton.

Konrath, S., Bushman, B. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2006). Attenuating the link between threatened egotism and aggression. Psychological Science, 17, 995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01818.x

Leary, M. R., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 32, pp. 1–62). San Diego, CA: Academic.

Leckelt, M., Küfner, A. C. P., Nestler, S., & Back, M. D. (2015). Behavioral processes underlying the decline of narcissists’ popularity over time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 856–871. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000057

Locke, K. D. (2009). Aggression, narcissism, self-esteem, and the attribution of desirable and humanizing traits to self versus others. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 99–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.10.003

Marigold, D. C., Holmes, J. G., & Ross, M. (2007). More than words: Reframing compliments from romantic partners fosters security in low self-esteem individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.232

Marigold, D. C., Holmes, J. G., & Ross, M. (2010). Fostering relationship resilience: An intervention for low self-esteem individuals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 624–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.02.011

McAdams, D. P. (1993). The stories we live by: Personal myths and the making of the self. New York: Morrow.

Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Gaughan, E. T., Gentile, B., Maples, J., & Keith Campbell, W. (2011). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis. Journal of Personality, 79, 1013–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x

Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102, 246–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.246

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (2000). Self-esteem and the quest for felt security: How perceived regard regulates attachment processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 478–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.3.478

Murray, S. L., Rose, P., Bellavia, G. M., Holmes, J. G., & Kusche, A. G. (2002). When rejection stings: How self-esteem constrains relationship-enhancement processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 556–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.3.556

Myers, E. M., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2012). How much do narcissists really like themselves? Using the bogus pipeline procedure to better understand the self-esteem of narcissists. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 102–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.09.006

Neiss, M. B., Sedikides, C., & Stevenson, J. (2002). Self-esteem: A behavioural genetic perspective. European Journal of Personality, 16, 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.456

Nelemans, S. A., Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., Olthof, T., Aleva, L., Goossens, F. A., et al. (2017). All egos were not created equal: Narcissism, self-esteem, and internalizing problems in children. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Nevicka, B., Ten Velden, F. S., De Hoogh, A. H. B., & Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2011). Reality at odds with perceptions: Narcissistic leaders and group performance. Psychological Science, 22, 1259–1264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417259

O’Mara, A. J., Marsh, H. W., Craven, R. G., & Debus, R. L. (2006). Do self-concept interventions make a difference? A synergistic blend of construct validation and meta-analysis. Educational Psychologist, 41, 181–206. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4103_4

Olson, K. R., & Dweck, C. S. (2008). A blueprint for social cognitive development. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00074.x

Park, S. W., & Colvin, C. R. (2015). Narcissism and other-derogation in the absence of ego threat. Journal of Personality, 83, 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12107

Paulhus, D. L. (1998). Interpersonal and intrapsychic adaptiveness of trait self-enhancement: A mixed blessing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1197–1208.

Paulhus, D. L., Harms, P. D., Bruce, N. M., & Lysy, D. C. (2003). The over-claiming technique: Measuring self-enhancement independent of ability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 890–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.890

Peck, A. (1976, June 3). Arnold Schwarzenegger: The hero of perfected mass. Rolling Stone. Retrieved from http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/features/the-hero-of-perfected-mass-19760603

Piff, P. K. (2014). Wealth and the inflated self: Class, entitlement, and narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213501699

Roberts, R., Woodman, T., & Sedikides, C. (2017). Pass me the ball: Narcissism in performance settings. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1290815

Robins, R. W., Trzesniewski, K. H., Tracy, J. L., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2002). Global self-esteem across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 17, 423–434. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.17.3.423

Rohner, R. P. (2004). The parental “acceptance-rejection syndrome”: Universal correlates of perceived rejection. American Psychologist, 59, 830–840. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.830

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sedikides, C., Campbell, W. K., Reeder, G. D., Elliot, A. J., & Gregg, A. P. (2002). Do others bring out the worst in narcissists? The “Others Exist for Me” illusion. In Y. Kashima, M. Foddy, & M. J. Platow (Eds.), Self and identity: Personal, social, and symbolic (pp. 103–124). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Thomaes, S., & Brummelman, E. (2016). Narcissism. In D. Cicchetti (Ed.), Developmental psychopathology (Vol. 4, 3rd ed., pp. 679–725). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., Stegge, H., & Olthof, T. (2008a). Trumping shame by blasts of noise: Narcissism, self-esteem, shame, and aggression in young adolescents. Child Development, 79, 1792–1801. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01226.x

Thomaes, S., Stegge, H., Bushman, B. J., Olthof, T., & Denissen, J. (2008b). Development and validation of the childhood narcissism scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90, 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802108162

Thomaes, S., Stegge, H., Olthof, T., Bushman, B. J., & Nezlek, J. B. (2011). Turning shame inside-out: “Humiliated fury” in young adolescents. Emotion, 11, 786–793. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023403

Tracy, J. L., Cheng, J. T., Robins, R. W., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2009). Authentic and hubristic pride: The affective core of self-esteem and narcissism. Self and Identity, 8, 196–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860802505053

Trzesniewski, K. H., Brent, M., & Robins, R. W. (2003). Stability of self-esteem across the life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.205

Verlinden, S., Hersen, M., & Thomas, J. (2000). Risk factors in school shootings. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 3–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00055-0

Vernon, P. A., Villani, V. C., Vickers, L. C., & Harris, J. A. (2008). A behavioral genetic investigation of the Dark Triad and the Big 5. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.09.007

Wallace, H. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2002). The performance of narcissists rises and falls with perceived opportunity for glory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.819

Walton, G. M. (2014). The new science of wise psychological interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413512856

Young, J. E. (1994). Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema-focused approach. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press.

Zitek, E. M., & Jordan, A. H. (2016). Narcissism predicts support for hierarchy (at least when narcissists think they can rise to the top). Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7, 707–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550616649241

Zuffianò, A., Eisenberg, N., Alessandri, G., Luengo Kanacri, B. P., Pastorelli, C., Milioni, M., et al. (2016). The relation of pro-sociality to self-esteem: The mediational role of quality of friendships. Journal of Personality, 84, 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12137

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Brummelman, E., Gürel, Ç., Thomaes, S., Sedikides, C. (2018). What Separates Narcissism from Self-esteem? A Social-Cognitive Perspective. In: Hermann, A., Brunell, A., Foster, J. (eds) Handbook of Trait Narcissism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92170-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92171-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)