Abstract

The relation between narcissism, agency, and self-esteem was comprehensively investigated by taking two subtypes of narcissism (grandiose and vulnerable) and two subtypes of agency (positive and negative) into account. In accordance with the Extended Agency Model by Campbell and Foster (2007), we proposed the relation between grandiose narcissism and self-esteem would be mediated by both positive and negative agency. Furthermore, we assumed both subtypes of agency would mediate the relation between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem. The sample, which was obtained by an online survey, included 323 participants (218 female, 105 male, age: M = 25.99, SD = 7.00). Validated measures of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, positive and negative agency, and self-esteem were administered. Hypotheses tests were based on the parallel multiple mediators model. Results showed that grandiose narcissism was positively correlated with self-esteem via the mediating influence of high positive agency. In contrast, grandiose narcissism negatively predicted self-esteem via the mediating influence of high negative agency. Vulnerable narcissism was negatively correlated with self-esteem via the mediating influence of both low positive agency and high negative agency. Results extend prior research in important ways by highlighting positive agency as the primary mediator, and negative agency as the secondary mediator, between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism on the one side and self-esteem on the other side.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Extended Agency Model (Campbell and Foster 2007) maintains that agency represents the narcissistic quality, which connects narcissism with self-esteem. Therefore, we consider self-esteem within the framework of narcissism and agency. The Extended Agency Model of narcissism states that narcissism is not oriented toward specific goals, but instead serves the more general goal of increasing and maintaining the self-regulation system serving the maintenance of the overbearing self-view of narcissists by employing suitable strategies (e.g., inflated self-views and self-evaluation maintenance). In addition, narcissists employ interpersonal skills like confidence and charisma. On the basis of these strategies and skills narcissistic self-regulation is unfolded which represents the core of the narcissistic self. Because the fundamental narcissistic qualities include self-initiative and approach strategies on the one hand, and lack of caring, neglect of others, and low interpersonal warmth on the other hand, the self-regulation system of narcissists is designated as an agency model.

Corresponding with the Extended Agency Model, Carlson et al. (2011) assume a deep-seated agentic self-perception, including an inflated self-view, lies at the center of the narcissistic self. Note that agentic self-perception is characterized by both positive agency and negative agency. Positive agency is defined as instrumental attitude based on independence and competitiveness, whereas negative agency includes self-absorption and devaluation of others (Spence et al. 1979). The Extended Agency Model in principle refers both to positive and negative agency, yet previous research investigating the determinants of narcissistic esteem has only focused on positive agency (negative agency was not investigated; Brown et al. 2016). The present research aims to fill this gap by simultaneously considering the influence of both positive and negative agency in this relationship.

Self-esteem represents conceptually the evaluative-affective component of the self (Wylie 1974). The concept of narcissism includes grandiose and vulnerable facets (Miller et al. 2017; Pincus and Lukowitsky 2010). At the center of grandiose narcissism lies an overbearing self-view that is based on an inflated self-esteem and exploitation of others (Emmons 1987; Raskin and Terry 1988). Grandiose narcissists are success-oriented, assertive, and egocentric. In addition, they express a strong need to be admired by others and invest a lot in self-promotion. In contrast, vulnerable narcissism is characterized by hidden feelings of grandiosity on the one hand, and by defensiveness, anxiety, insecurity, and social avoidance on the other hand (cf., Cain et al. 2008; Dickinson and Pincus 2003; Rohmann et al. 2012). Vulnerable narcissists fluctuate back and forth between feelings of superiority and inferiority (Wink 1991; cf., Oltmanns and Widiger 2018).

In the influential book, The Duality of Human Existence (Bakan 1966), the concept of agency, which is the part of the self-concept referring to self-expansion, self-control, assertiveness, and strength, was described. This account proposes agency is more typical of men’s gender role than of females’ gender role, a view now widely supported by empirical evidence (for a summary see Helgeson 2003). Following this account, and in line with literature supporting independent dimensions of agency (Bakan 1966; Rohmann and Bierhoff 2013; Runge et al. 1981; Spence et al. 1979), two measures of agency have been developed. The first dimension is ‘positively valued masculinity’ (M+), characterized by traits including ‘independence’ and ‘self-confidence’. The second dimension is ‘negatively valued masculinity’ (M-), characterized by traits including ‘arrogance’ and ‘hostility’. For the sake of brevity, from here on we refer to these agentic dimensions as positive agency and negative agency, respectively.

According to the Extended Agency Model, grandiose narcissism is associated with an agentic stance. Therefore, we assumed grandiose narcissism would be positively related to positive agency. Vulnerable narcissists oscillate between feelings of superiority and inferiority, exhibiting a fragile self-confidence. Their insecurity and anxiety restrict their freedom of action and their self-doubts dampen their optimism (Wink 1991). Therefore, it is plausible to assume that high vulnerable narcissism is related to low positive agency. This reasoning is supported by empirical evidence demonstrating vulnerable narcissism to signal a low self-efficacy (Brookes 2015) and a low promotion focus (Hanke et al. 2019).

Grandiose narcissists who have at their disposal many interpersonal talents also express unpleasant interpersonal behavioral tendencies (e.g., neglect and devaluation of others), which are reflected in ratings by acquaintances as disagreeable, unreliable, and dislikable (Carlson et al. 2011). In addition, empirical research with 15–16 year old’s indicated that grandiose narcissists tend to behave aggressively in both a proactive and reactive fashion (Fossati et al. 2010). On the basis of this evidence it is likely that grandiose narcissism is positively associated with negative agency.

Vulnerable narcissists feel disappointed, not so much by themselves but by others. Therefore, they are likely to perceive others in negative terms, which corresponds well with characteristics of negative agency (e.g., negative interactions with others, hostility, and arrogance; Helgeson 2003). Therefore, we expected a positive link between vulnerable narcissism and negative agency.

In correspondence with the Extended Agency Model, empirical evidence indicates that positive agency is positively correlated with self-esteem (Helgeson 2003). In contrast, evidence demonstrating a relationship between negative agency and self-esteem is less consistent. In instances where a significant relationship has been found, it was negative rather than positive (Helgeson 2003; Rohmann and Bierhoff 2013).

Empirical results (Brown et al. 2016; Dickinson and Pincus 2003; Rohmann et al. 2012; Wink 1991) indicate that grandiose narcissism should be positively related to self-esteem, whereas vulnerable narcissism should be negatively linked to self-esteem. Therefore, it is likely that high grandiose narcissism fuels high narcissistic esteem, which might be impaired by high vulnerable narcissism.

Hypotheses

Conceptual links between grandiose narcissism and narcissistic esteem are set-out in the Extended Agency Model of narcissism (Campbell and Foster 2007). In correspondence with this model, research indicates narcissism and self-esteem are systematically related and that this relationship is mediated by positive agency (Brown et al. 2016). More specifically, grandiose narcissism was positively related to self-esteem, a relationship mediated by positive agency. In contrast, vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem were negatively related via the mediating influence of reduced positive agency. This research represents the starting point for the derivation of H1a which assumes the link between grandiose narcissism and self-esteem is mediated by positive agency: [GN (+) ➔ Apos (+) ➔ SE (+)].

A second trajectory from grandiose narcissism to self-esteem, which is captured by H1b, focuses on negative agency as the mediator. Because it is plausible that grandiose narcissism is positively associated with negative agency and that negative agency is negatively related to self-esteem, it is hypothesized that grandiose narcissism will negatively relate to self-esteem via negative agency: [GN (+) ➔ Aneg (+) ➔ SE (−)].

Furthermore, it is assumed in H2 that vulnerable narcissism predicts self-esteem via positive and negative agency. Specifically, H2a predicts (in correspondence with Brown et al. 2016) the negative link between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem will be mediated by low positive agency [VN (+)➔ Apos (−) ➔ SE (+)] given the plausibility that vulnerable narcissism negatively relates to positive agency, which in turn is positively related to self-esteem.

Finally, because vulnerable narcissism is assumed to be positively related to negative agency, and because negative agency seems to have negative implications for self-esteem, it is likely the negative link between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem will be mediated by negative agency (H2b): [VN (+) ➔ Aneg (+) ➔ SE (−)].

Method

Participants

The sample includes 323 participants [218 (67%) female, 105 (33%) male]. Their mean age was 25.99 years (SD = 7.00) with a range from 18 years to 61 years. Most participants were students (62%), 26% were employed, 8% were apprentices, and 4% were unemployed, retired, homemaker/caretaker, or did not specify their occupation.

Procedure and Materials

Participants responded to campus-wide flyers and invitations via Facebook. Data collection including demographic information and personality variables was based on the software EFS Survey from QuestBack Unipark. All personality variables were measured by validated questionnaires.

Sample size estimation for correlation analyses was based upon achieving .8 statistical power, with error probability of .05, and an estimated medium effect size of .3 (cf., Cohen 1988). Using version 3.1 of the G*power program (Faul et al. 2007), the required sample size turned out to be 84 (two-tailed test). In addition, we determined the estimated medium-sized effects for mediation analysis pertaining to the two mediation paths alpha and beta, using empirical estimates derived from simulation of bias-corrected bootstrap tests of mediation (Fritz and MacKinnon 2007, Table 3). The sample size estimated was 71. Our sample size of 323 participants thus fully meets the estimated requirements for correlation and mediation analyses.

Grandiose Narcissism

The German Version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI, Raskin and Terry 1988; Schütz et al. 2004) was employed as the measure of grandiose narcissism. In correspondence with Raskin and Terry (1988), the German NPI includes 40 forced-choice items, each contrasting a narcissistic (coded as 1) with a non-narcissistic (coded as 0) statement. It is well validated and exhibits a similar factor structure as the original NPI. The NPI-items correspond with the criteria of the Narcissistic Personality Disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V, American Psychiatric Association 2013).

Vulnerable Narcissism

The covert form of narcissism was measured with the Narcissistic Inventory (NI; Deneke and Hilgenstock 1989), which was derived from self-theory (Kohut 1971). We used the abridged 36-items version (NI-R-36; Rohmann et al. 2012) employing five-point response scales (1 = not at all true; 5 = completely true). The NI-R-36 correlates highly with the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Hendin and Cheek 1997), a frequently used measure of vulnerability, thus indicating its validity (Rohmann et al. 2012). In addition, The NI-R-36 corresponds with the criteria of the Narcissistic Personality Disorder in the DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association 2013; Rohmann et al. 2012). This is a strong argument for using the NI-R-36 in comparison with the HSNS, which captures several diagnoses of personality disorders outlined in the DSM (Fossati et al. 2009).

Positive Agency

The Extended Personal Attributes Questionnaire (EPAQ; Spence et al. 1979) includes measures of positive and negative agency. The attributes are presented using trait terms. The item “competitive” was omitted from the German scale because its desirability was negatively evaluated for both women and men. Spence, Helmreich, and their German coworkers translated the EPAQ into German. The authors concluded: “With the modifications noted above, the results obtained from this German sample of high school and college students with the GEPAQ closely replicated those obtained from U.S. students with the EPAQ” (Runge et al. 1981, p.159/160). The resulting questionnaire of positive agency from the German Extended Personal Attributes Questionnaire (GEPAQ-M+; Runge et al. 1981) includes seven trait terms (e.g., independent) which represent the male stereotype and which are socially desirable in both genders. For each item, five-point response scales were employed.

Negative Agency

The one-sided focus on the self, combined with the neglect of others, represents the core of negative agency. The corresponding scale from the German Extended Personal Attributes Questionnaire (GEPAQ-M-; Runge et al. 1981) consists of nine trait terms referring to instrumental traits, which exhibit low social desirability. Items, which are rated on five-point response scales, express either self-absorption (e.g., arrogant) or a negative view of others (e.g., hostile).

Self-Esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) was employed as a measure of dispositional self-esteem. It is a measure of global self-esteem and exhibits good reliability and validity (Fleming and Courtney 1984). The German adaptation of the RSES (von Collani and Herzberg 2003), which includes 4-point response scales (0 = not at all true; 3 = completely true), also measures global self-esteem.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive information about narcissism, agency, and self-esteem. In general, internal consistencies were either satisfactory (NPI, GEPAQ-M+, GEPAQ-M-) or good (NI-R-36, RSES). The respondents expressed relatively low agreement with grandiosity and negative agency, but moderate agreement with vulnerable narcissism, self-esteem, and positive agency. Men scored higher than women on grandiose narcissism, positive agency, and negative agency.

Correlational Analyses

As expected, grandiose and vulnerable narcissism were correlated significantly positively (see Table 2). The common variance between both measures was 7.84%. Partial correlations (see Table 2, below the diagonal) represent ‘pure’ grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, respectively. For example, the relationship between grandiose narcissism and self-esteem was controlled for vulnerable narcissism.

The significant correlation between grandiose narcissism and positive agency explained 24.01% of the variance. The association was even stronger for partial correlations, which control for vulnerable narcissism. The significant negative correlation between vulnerable narcissism and positive agency explained 3.61% of the variance. The partial correlation controlling for grandiose narcissism was quite strong, explaining 15.21% variance.

Furthermore, the common variance between grandiose narcissism and negative agency was 8.41%, whereas the common variance of 5.29% after partialling out vulnerable narcissism was somewhat lower, but still highly significant. In addition, the common variance between vulnerable narcissism and negative agency was 5.76%. On the level of partial correlations, the positive association between both variables is somewhat weaker, with common variance of 2.89%.

As expected, positive agency and self-esteem were correlated highly. The common variance of 33.64% between both variables was quite substantial. Furthermore, the results support the expected negative relationship between negative agency and self-esteem, although the common variance of 1.96% was quite small.

In correspondence with the Extended Agency Model, grandiose narcissism positively predicted self-esteem, with common variance of 9.61%. In addition, the expectation that high vulnerable narcissism is associated with lack of self-esteem was supported, with a common variance of 5.29%. On the level of partial correlations, this negative relationship was somewhat more pronounced.

Hypotheses Tests: Mediation

H1 and H2 refer to the mediation of the relationship between narcissism and self-esteem via agency. These mediation hypotheses were statistically examined with the SPSS macro of the PROCESS subroutine (model 4), which allows for the examination of the parallel multiple mediator model (Hayes 2013, p. 125). Note that the two variable mediator model permits a stringent test of hypotheses. The 95% confidence interval (CI) was employed. If the lower and higher limit of the CI do not include the value 0, the mediation is significant at the 5% level. The number of bootstrap samples for the calculation of the bias-corrected bootstrap CI was 10,000. In these analyses, gender and age of participants served as control variables. Furthermore, we included vulnerable narcissism as a covariate in testing H1 and grandiose narcissism as a covariate in testing H2.

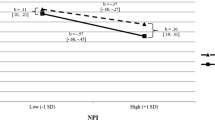

H1a, which connects grandiose narcissism with self-esteem via positive agency, was abbreviated as [GN (+) ➔ Apos (+) ➔ SE (+)]. H1b, which connects grandiose narcissism with self-esteem via negative agency, was abbreviated as [GN (+) ➔ Aneg (+) ➔ SE (−)]. H1a and H1b, respectively, go beyond correlational associations by stating that the effect of grandiose narcissism on self-esteem is mediated by both positive agency and negative agency. Therefore, mediation via positive agency was controlled for by the mediation via negative agency and vice versa. The corresponding parallel multiple mediator model is depicted in the upper half of Fig. 1.

Multiple mediation analysis with grandiosity (top half) and vulnerability (bottom half) as independent variables. Path values represent unstandardized regression coefficients. The value in parentheses represents the effect of grandiosity/vulnerability on self-esteem after the inclusion of the mediating variables. N = 323; **p < .01. ***p < .001

The total effect of grandiose narcissism on self-esteem (c-path) was highly significant, c = .44, SE = .05 (95% CI [.33, .54]). A significant mediation via positive and negative agency in combination occurred with a bootstrap estimation point = .25, SE = .04 (95% CI [.17, .33]). In accordance with H1a, the indirect effect of positive agency was significant with a bootstrap estimation point of .28, SE = .04 (95% CI [.20, .36]). In correspondence with H1b, the indirect effect via negative agency was also significant with a bootstrap estimation point = −.03, SE = .01 (95% Cl [−.06, −.01]).

Finally, the parallel multiple mediator model includes a test of the relative strength of the mediation via the parallel mediators (see Appendix). This C1 (indirect effect contrast M+ minus M-) was highly significant, Effect = .31, Boot SE = .04 (95% Cl [.23, .39]) indicating that the mediation via positive agency was stronger than the mediation via negative agency. Note that the mediation via agency is only partial because the relationship between grandiose narcissism and self-esteem was still significant after controlling for agency, c’ = .19, SE = .06 (95% CI [.07, .31]).

H2a and H2b were abbreviated as [VN (+)➔ Apos (−) ➔ SE (+)] and [VN (+) ➔ Aneg (+) ➔ SE (−)]. H2a is based on positive agency as mediator, whereas H2b is based on the mediator negative agency (see lower half of Fig. 1).

The total effect of vulnerable narcissism on self-esteem (c-path) was highly significant, c = −.32, SE = .05 (95% CI [−.42, −.21]). The sign of the c-path was negative. In accordance with the hypothesis, the mediation effect was significant, bootstrap estimation point = −.18, Boot SE = .03, (95% CI [−.25, −.12]). Supporting H2a, the link between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem was mediated via positive agency, bootstrap estimation point = −.15, Boot SE = .03 (95% CI [−.21, −.10]). In addition, and supporting H2b, the link between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem was mediated via negative agency, bootstrap estimation point = −.03, Boot SE = .01 (95% CI [−.06, −.01]).

Finally, the test of the relative strength of the mediation via the parallel mediators (indirect effect contrast M+ minus M-) was highly significant, Effect = −.12, Boot SE = .03 (95% Cl [−.19, −.06]) indicating that the mediation via positive agency was stronger than the mediation via negative agency (see Appendix). Note that the mediation via agency is only partial because the link between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem was still significant after controlling for agency, c’ = −.14, SE = .05 (95% CI [−.24, −.04]).

Discussion

The Extended Agency Model (Campbell and Foster 2007) emphasizes that the inflated self-view of the narcissistic self reflects a problematic self-concern, which might well be rooted in negative agency. Therefore, it is quite likely that negative agency, alongside positive agency, is involved in the transmission of narcissistic tendencies to self-esteem.

From the Extended Agency Model, we adopted the idea that agency constitutes the key construct connecting narcissism with its consequences. The results confirmed that grandiose narcissism was positively related to positive agency, self-esteem, and negative agency, and that positive and negative agency were positively and negatively associated with self-esteem, respectively. In addition, vulnerable narcissism was, as expected, negatively correlated with positive agency and self-esteem, respectively, and positively correlated with negative agency.

Results of the parallel multiple mediator model confirmed our assumption that the link between grandiose narcissism and self-esteem is mediated by positive agency (H1a). This evidence is consistent with previous results of a partial mediation by positive agency of the effect of grandiose narcissism on self-esteem (Brown et al. 2016). The partial mediation in this study indicates that other unmeasured variables are likely to influence the level of self-esteem (e.g., social feedback and social comparison; cf., Harter 1993). In addition, the inclusion of negative agency contributes to a more comprehensive account of the level of self-esteem depending on grandiose narcissism. Nevertheless, the importance of the path via negative agency is secondary compared with the primary path via positive agency outlined in H1a. Remarkably, both trajectories have opposite effects on self-esteem. Whereas the trajectory via positive agency boosts self-esteem, the trajectory via negative agency dampens it. But because the primary trajectory via positive agency is stronger, overall, grandiose narcissism is positively related to self-esteem.

A third trajectory connecting narcissism and self-esteem includes vulnerable narcissism, positive agency, and self-esteem. By employing the parallel multiple mediator model, we examined H2a and H2b simultaneously. Previous research (Brown et al. 2016) indicated that vulnerable narcissism was negatively linked to positive agency, which in turn was positively connected with self-esteem. This pattern of results was confirmed by the statistical analysis replicating the previous results. Results also corroborated H2b because the mediation between vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem via negative agency was significant.

Three major insights emerge from this research. First, grandiose and vulnerable narcissism diverge from each other in certain respects while they correspond with each other in other respects. On the one hand, grandiose narcissism was positively associated with positive agency whereas vulnerable narcissism was negatively associated with it. In addition, the results indicate that grandiose narcissism was related to high self-esteem whereas vulnerable narcissism was related to lack of self-esteem (cf., Dickinson and Pincus 2003; Wink 1991). On the other hand, similarities of both facets of narcissism were evident, too, because both facets correlated positively with each other. In addition, they both correlated positively with negative agency. In the case of vulnerable narcissism that is no surprise. In the case of grandiose narcissism, the assumption of a positive relationship was derived from negative facets of grandiosity because it is plausible to assume that the component of entitlement/exploitation which represents a basic dimension of grandiose narcissism (Brailovskaia et al. 2019; Emmons 1987), has unfavorable effects on interpersonal relations and is maladaptive.

Second, positive agency functions as a strong mediator between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism on the one hand, and self-esteem on the other. But the sign is different with grandiose narcissism implying high positive agency and vulnerable narcissism implying low positive agency.

Third, negative agency also serves as mediator between grandiose/vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem. But whereas positive agency turned out to be the primary mediator, negative agency was of secondary importance as a mediator. Note that endorsement of M+ was considerably higher than endorsement of M-. A paired t-test revealed that endorsement of M+ was significantly higher than of M-, t (322) = 27.61, p < .001. One might speculate that – in contrast to positive agency – a floor effect for negative agency occurred which attenuated the correlation with self-esteem. But this speculation is not convincing considering the similar standard deviations associated with M+ and M-. In addition, the internal consistencies of both scales are identical. The psychometric properties of M+ and M- essentially correspond with each other. Therefore, positive agency arguably reflects a more compelling mediator in H1 and H2 than negative agency. Further research is needed to clarify this issue.

The present results are of particular importance because they indicate that both positive and negative agency mediate the association between narcissism and self-esteem. One interesting finding is that grandiose narcissism exerts its positive influence on self-esteem via positive agency, and its negative influence on self-esteem via negative agency.

If agentic self-concept is characterized by arrogance and devaluation of others, which equals unmitigated/negative agency, self-esteem will likely be impaired. The inclusion of negative agency in the analysis of the trajectories from narcissism to self-esteem is revealing. First, the mediation model including both positive and negative agency is more comprehensive from a theoretical viewpoint. Second, it is important that the influence of negative agency in applied settings is considered because low self-esteem is related to poor psychological health (Leary et al. 1995; Sedikides et al. 2004). The results indicate that low self-esteem might be alleviated not only by increasing the level of positive agency but also by reducing the level of negative agency. On the one side, positive agency constitutes a protective factor, which enhances self-esteem. On the other side, negative agency contributes to the impairment of self-esteem and therefore undermines self-regard. Therefore, two types of interventions are available to foster treatment success with clients who suffer from low self-regard: interventions which emphasize aspects of positive agency (e.g., heightening self-confidence), and interventions which focus on eliminating aspects of negative agency (e.g., reducing hostility).

Limitations and Future Research

Two questions remain. The sample is not representative of the general population because more than half of the participants were students and younger participants were overrepresented. Although it is quite unlikely that these sample characteristics influenced the main results, future research should endeavor to recruit a sample reflective of the general population (i.e., greater range of age and education levels). In addition, future studies should use different measures of narcissism, agency, and self-esteem for making the findings more generalizable across different operational definitions of the variables included in the tests of the parallel multiple mediator models.

Finally, a statistical mediation effect does not necessarily imply true mediation in a causal sense. But the high consistency of confirmation of H1 and H2 indicates that the assumption that positive and negative agency function as mediators between narcissism and self-esteem received considerable empirical support.

Conclusions

Present results illustrate that it is theoretically profitable to distinguish not only between two facets of narcissism but also between two facets of agency in order to derive hypotheses from the Extended Agency Model of narcissism. Results extend prior research in important ways by highlighting both positive agency and negative agency as important mediators between grandiose/vulnerable narcissism and self-esteem.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (fifth ed.). Washington: American Psychiatric Association.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence. Chicago: Rand McNally. https://doi.org/10.1177/004056396702800321.

Brailovskaia, J., Bierhoff, H.-W., & Margraf, J. (2019). How to identify narcissism with 13 items? Validation of the German narcissistic personality inventory −13 (G-NPI-13). Assessment, 26, 630–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191117740625.

Brookes, J. (2015). The effect of overt and covert narcissism on self-esteem and self-efficacy beyond self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 172–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.013.

Brown, A. A., Freis, S. D., Carroll, P. J., & Arkind, R. M. (2016). Perceived agency mediates the link between the narcissistic subtypes and self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.055.

Cain, N. M., Pincus, A. L., & Ansell, E. B. (2008). Narcissism at the crossroads: Phenotypic description of pathological narcissism across clinical theory, social/personality psychology, and psychiatric diagnosis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.006.

Campbell, W. K., & Foster, J. D. (2007). The narcissistic self: Background, an extended agency model, and ongoing controversies. In C. Sedikides & S. J. Spencer (Eds.), The self. Frontiers of social psychology (pp. 115–138). New York: Psychology Press.

Carlson, E. N., Naumann, L. P., & Vazire, S. (2011). Getting to know a narcissist inside and out. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder (pp. 285–299). Hoboken: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118093108.ch25.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Deneke, F.W., & Hilgenstock, B. (1989). Das Narzissmusinventar [The narcissism inventory]. Bern, Switzerland: Huber.

Dickinson, K. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2003). Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 188–207. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.17.3.188.22146.

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.11.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Fleming, J. S., & Courtney, B. E. (1984). The dimensionality of self-esteem: II. Hierarchical facet model for revised measurement scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 404–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.2.404.

Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Grazioli, F., Dornetti, L., Marcassoli, I., Maffei, C., & Cheek, J. (2009). Tracking the hypersensitive dimension in narcissism: Reliability and validity of the hypersensitive narcissism scale. Personality and Mental Health, 3, 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.92.

Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Eisenberg, N., & Maffei, C. (2010). Relations of proactive and reactive dimensions of aggression to overt and covert narcissism in nonclinical adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 36, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20332.

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18, 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x.

Hanke, S., Rohmann, E., & Förster, J. (2019). Regulatory focus and regulatory mode: Keys to narcissists' (lack of) life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.039.

Harter, S. (1993). Causes and consequences of low self-esteem in children and adolescents. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Self-esteem. The puzzle of low self-regard (pp. 87–116). New York: Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-8956-9_5.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12050.

Helgeson, V. S. (2003). Gender related traits and health. In J. Suls & K. A. Walston (Eds.), Social psychological foundations of health and illness (pp. 367–394). Oxford: Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470753552.ch14.

Hendin, H. M., & Cheek, J. M. (1997). Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: A reexamination of Murray’s Narcism scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 588–599.

Kohut, H. (1971). The analysis of the self. New York: International Universities Press.

Leary, M. R., Schreindorfer, L. S., & Haupt, A. L. (1995). The role of low self-esteem in emotional and behavioral problems: Why is low self-esteem dysfunctional. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14, 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1995.14.3.297.

Miller, J. D., Lynam, D. R., Hyatt, C. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2017). Controversies in narcissism. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244.

Oltmanns, J. R., & Widiger, T. A. (2018). Assessment of fluctuation between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: Development and initial validation of the FLUX scales. Psychological Assessment, 30, 1612–1624. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000616.

Pincus, A. L., & Lukowitsky, M. R. (2010). Pathological narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 421–446. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131215.

Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 890–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890.

Rohmann, E., & Bierhoff, H. W. (2013). Geschlechtsrollen-Selbstkonzept und Beeinträchtigung des psychischen Wohlbefindens bei jungen Frauen. [Gender-role self-concept and psychological distress in young women]. Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie, 21, 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1026/0943-8149/a000102.

Rohmann, E., Neumann, E., Herner, M. J., & Bierhoff, H. W. (2012). Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: Self-construal, attachment and love in romantic relationships. European Psychologist, 17, 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000100.

Runge, T. E., Frey, D., Gollwitzer, P., Helmreich, R. L., & Spence, J. T. (1981). Masculine (instrumental) and feminine (expressive traits): A comparison between students in the United States and West Germany. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 12, 142–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022181122002.

Schütz, A., Marcus, B., & Sellin, I. (2004). Die Messung von Narzissmus als Persönlichkeitskonstrukt: Psychometrische Eigenschaften einer Lang- und einer Kurzform des Deutschen NPI (Narcissistic Personality Inventory) [Measuring narcissism as a personality construct: Psychometric properties of a long and a short version of the German Narcissistic Personality Inventory]. Diagnostica, 50, 202–218.

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., Gregg, A. P., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy? Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 400–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.400.

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R. L., & Holahan, C. K. (1979). Negative and positive components of psychological masculinity and femininity and their relationships to self-reports of neurotic and acting out behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1673–1682. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1673.

Von Collani, G., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2003). Eine revidierte Fassung der deutschsprachigen Skala zum Selbstwertgefühl von Rosenberg [A revised version of the German adaptation of Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale]. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie, 24, 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1024//0170-1789.24.1.3.

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590.

Wylie, R. C. (1974). The self-concept. Lincoln: Nebraska University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Faculty of Psychology, Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, on November 14, 2017.

Informed Consent

The data were obtained by an online study. Participants gave their online informed consent.

Declarations of Interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 59.1 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rohmann, E., Brailovskaia, J. & Bierhoff, HW. The framework of self-esteem: Narcissistic subtypes, positive/negative agency, and self-evaluation. Curr Psychol 40, 4843–4850 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00431-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00431-6