Abstract

In recent years, there have been numerous parent training studies of children with autism that provide strong empirical support for these parent-mediated approaches. However, to date, most report findings from mothers, and fathers continue to be underrepresented. This is unfortunate in that fathers have been prominent figures throughout history. Furthermore, there is clinical and preliminary empirical evidence that informed and empowered fathers can significantly contribute to child development and the overall quality of life for all family members. Thus, the purpose of this chapter is to discuss current literature about the unique role that fathers play in raising a child with autism, identify common paternal reactions to an autism diagnosis, describe how male learning styles may affect parent training approaches, discuss clinical implications related to father involvement, and identify areas for future research.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Background Related to Roles of Fathers

Throughout history, fathers have remained a prominent figure in the family even as their roles in society have changed and evolved. Pleck (1982) presents a historical account of the father’s role beginning in colonial times through the 1970s where the feminist influence is described. This evolution from strong patriarch and breadwinner to co-parent is striking and appears to have been influenced by factors such as the following: (a) society’s current view of parental roles that includes a shift in expectations of fathers, (b) increased maternal employment, (c) evidence of the father’s influence on child development, and (d) demographic profiles of modern families (McBride & Lutz, 2004).

Even with the notable societal shift to co-parenting, most parent-child intervention studies only report findings from mothers, and fathers continue to be underrepresented in the literature (Flippin & Crais, 2011). For this reason, the author and colleagues made a deliberate departure from more traditional parent training to focus exclusively on fathers. The ultimate aim was to help fathers interact in ways they felt were constructive with their children and empower them to train other family members to use strategies for promoting socialization and language development. Through years of this type of in-home participation, we have observed fathers interact with their children with autism and noted that informed and empowered fathers can significantly contribute to child development and the overall quality of life for all family members. Thus, the purpose of this chapter is to discuss current literature about the unique role that fathers play in raising a child with autism, identify common paternal reactions to an autism diagnosis, describe how male learning styles may affect parent training approaches, discuss clinical implications related to father involvement, and identify areas for future research.

What We Know about Fathers

Lamb (1976) was the first to document the positive influence of fathers in child development. His seminal work was produced in the mid-1970s at a time when most social scientists doubted that fathers significantly influenced the development of their children, especially their daughters. His early and subsequent work has primarily focused on three areas: father engagement, accessibility, and responsibility (Lamb & Tamis-Lemonda, 2004).

Theoretical Models

In addition to Lamb’s organization of his research in the stated areas, Doherty, Kouneski, and Erickson (1998) have created a theoretical framework to assist in the development of a systematic knowledge base to guide our understanding of the paternal role in child development . This model indicates that a number of mother, child, father, and contextual factors may influence father involvement. For example, a father’s sense of capability, self-efficacy, and psychological well-being may greatly influence his desire to participate and succeed in his paternal role (Doherty et al., 1998). In addition, “role salience” (if the father is fully engaged in his role) may indicate how likely a father is to assume the role given contextual factors over time (Stryker, 1991). Finally, the father’s involvement in child rearing often depends on the mother’s attitudes and expectations about his role. In some cases, the mother acts as a “gatekeeper” and determines what aspects of child raising the father is permitted to do. In our work, we have noted that mothers often assume caretaking duties that become integral to their identities and have difficulty relinquishing even the most stressful aspects of their roles to fathers. As mentioned, child characteristics such as gender also play a part in determining father involvement. For example, Flouri and Buchanan (2003) found that fathers spent more time with their sons than daughters. This suggests possible gender identification which, in turn, could affect paternal expectations of the child and the father-son relationship.

Clinical Insights

Father involvement may also depend on whether the father perceives that he can make a positive difference in the child’s behavior or overall quality of life. This was clearly illustrated by one father who was initially very reticent to participate in our in- home training program. In fact, the day that we arrived to enroll the family, he was outside gardening with no intention to meet with us. His wife joined us in the living room and was happy to complete the necessary paperwork. After we explained to the mother that the focus of our training was directly on fathers, she accompanied us to the front yard where the father was grooming his hedges. At our approach, he stopped his work and admitted that he felt reluctant to be involved with his child who had severe ASD. “I can work in my yard and accomplish great things. Our yard is the pride of the neighborhood. I can spend the same amount of time, or even more, with my son, and nothing changes. It makes no difference.” Grateful for the father’s candidness, we were able to convince him to participate in our program. Even though his son’s progress was slow, the son responded positively, and the father found that he could successfully execute the play-based intervention and actually “had fun” doing it. This had unexpected generalization effects: not only did the father become more involved with his child at home, but he also eventually replaced his wife as the family’s school liaison and primary vocal advocate. This is a clear example of how empowering fathers can enhance their self-efficacy and produce positive outcomes for the family.

Effects of Paternal Stress

It is well-known that raising a child with ASD can be very stressful (Hall & Graff, 2011; Little, 2013). In their study of parents of children with ASD, Hastings et al. (2005) found that fathers’ stress was positively correlated with maternal anxiety and depression and that maternal and paternal depression significantly predicted partner stress. These findings were similar to those of Kayfitz, Gragg, and Orr (2010) who noted that fathers’, but not mothers’, positive experiences were negatively related to their partners’ reports of parenting stress. Although these results are preliminary, they show that focusing on mothers at the exclusion of fathers only “paints half of the picture” because the marital relationship influences the family as a whole. Thus, if parental stress is not examined, there is no opportunity to intervene appropriately when needed.

Indeed, evidence demonstrates that fathers and mothers differ in their psychological experiences (e.g., stress, reactions, and expression of stress and anxiety) related to their child with ASD. In order to define the experiences and reactions of fathers to an ASD diagnosis, Hastings and colleagues (2005) have focused on fathers and report that fathers employ different coping strategies for stress than mothers when raising a child with ASD. They and others also report that rates of depression, anxiety, and overall distress for fathers differ from those of mothers (Davis & Carter, 2008). Our clinical experiences have confirmed these findings and revealed that while mothers may overtly express stress, fathers also experience it but often remain silent. For example, we found that both mothers and fathers scored over the 90th percentile on the Parenting Stress Index even though the fathers did not appear to be or stressed or verbalize this emotion (Bendixen, Elder, Donaldson, Kairella, Valcante, & Ferdig, 2011). We also observed that mothers were more likely to admit that they were depressed, whereas fathers reacted to depression in other ways, such as working more outside the home. This has implications for healthcare providers who may have to “dig deeper” to identify stress and depression in fathers. They may also find that interventions for addressing depression and lowering stress may need to be tailored with fathers in mind.

Father Reactions to an ASD Diagnosis

In addition to what has already been mentioned, we have noted that fathers may react and adapt differently to an ASD diagnosis than mothers. While gender differences in reaction and adaptation to an ASD diagnosis are not well-documented in the literature, there are important clinical implications, as noted in the following vignette:

Case Vignette

Johnny was born after a normal pregnancy, labor, and delivery to John and Melissa. The parents had tried for years to conceive and both were in their mid-thirties. They had been thrilled to learn not only of the pregnancy but that they were having a boy. John, like many expectant fathers, set about making future plans for college, baseball, soccer, and father-son campouts. What fun they would have together! When Johnny was about 15 months old, Melissa noted that he did not act quite like the other children at the playground: he was nonverbal, avoided direct eye contact, used her hand like a tool to reach things he wanted, and had great difficulty with changes in routine. John, on the other hand, who was a brilliant engineer, was not concerned and even reminded Melissa that he did not speak until he was 4 years old. Several months passed and Melissa’s concern mounted. John traveled frequently with his work, and Melissa often found herself alone trying to socially engage her son and manage his tantrums.

As illustrated by this case vignette (where the names are fictitious but the story is not), one of the first challenges for parents of children with ASD is acquiring and accepting an ASD diagnosis. Often mothers are the first to suspect that there is abnormal development before an official diagnosis is made and that fathers are more reticent to accept an ASD diagnosis. This may be because, in many cases like our vignette, mothers are typically more involved in the day-to-day caregiving and thus may be more sensitive in discerning communication and socialization delays as well as behavioral problems. Second, we have observed that fathers may initially dismiss maternal concerns and, as in the case vignette, explain that they were also “slow to talk” and socially shy and awkward when they were young. Finally, Ingersoll and Hamrick (2011) explain that some fathers of children with ASD may express the broader autism phenotype (BAP), making it difficult for them to recognize the core features of ASD in their children, particularly the deficits in social and communication skills.

However, once the diagnosis is made, both parents may experience a period of mourning over the loss of their “perfect child” or the one they had imagined. For the father in our vignette, he had to accept the fact that his son might not go to college or achieve other high academic goals. Learning to accept this reality was complicated by the fact that, unlike some other developmental and neurological childhood disorders, children with ASD are frequently physically normal and even exceptionally attractive. His mother later explained, “God knew what he was doing when he created our son. He understood how challenging it would be so He made him really cute.”

In addition to the initial denial and subsequent mourning, fathers often go through other phases similar to those described by Kubler-Ross (1969): denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Keeping these phases and related reactions in mind, it is particularly important for healthcare providers to understand that many paternal reactions are actually a normal and expected part of the grieving process. A common example is anger that may even be targeted at those trying to help the family. Rather than reacting to the anger, well-informed providers can be instrumental in helping fathers as well as mothers navigate through the grieving process to access the situation and recalibrate to what Ross and Kessler (2007) refer to as a “new normal.” In our experience, we have also noted that fathers may have more difficulty moving past the denial phase than mothers.

Because fathers can play a significant role in their child’s development, it is important to help them through the grieving process in a way they feel is beneficial. For example, clinicians can encourage fathers to assume and maintain key roles rather than conclude that “mothers do it better.” In our experience, fathers require concrete direction about techniques they can use with their child, as well as evidence that the techniques will make a difference. Once again, much of what we know about father involvement comes from anecdotal reports and observations such as ours. This is because most parent training studies with empirical data usually involve only mothers and the word “parent” is misleading. Thus, we have limited scientific evidence about fathers and the potential impact they can have. However, preliminary evidence suggests that fathers may be able to positively influence their children’s development, and father contributions to child development may even go beyond those made by mothers (Pleck & Masciadrelli, 2004).

Applying Male Learning Principles

In addition to limited reports regarding father-focused parent training, there is evidence from clinical practice and the literature that fathers and mothers may not learn in the same manner or benefit equally from certain popular parent training modalities. In fact, research confirms that gender plays a role in how individuals obtain knowledge. In a self-report investigative study conducted at a Midwestern University in the United States, researchers used a questionnaire with six domains, realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, and conventional, each with four variables—performance accomplishments, vicarious learning, social persuasion, and physiological arousal to determine the influence of gender on learning. Men reported greater learning experiences in the traditionally masculine realistic and investigative domains , while women’s learning experiences were reported as predominantly social, a traditionally female domain. Similarly, in a Canadian study that assessed groups of students from grades 5, 8, and 11, Hunter, Gambell, and Randhawa (2005) revealed that in all male or predominantly male groups, language use was significantly less than in groups made up of all or predominantly females. They concluded that the education system is primarily focused on oral and aural learning skills favoring female learners. This finding suggests that parent training approaches that are highly dependent on verbal instruction may be more effective if they include written materials and examples to which fathers can relate. In a more geographically diverse study, Honigsfeld and Dunn (2003) looked at high school students from five countries including Bermuda, Brunei, Hungary, Sweden, and New Zealand to determine differences in gender learning styles in varied nations. They found that males showed significantly more kinesthetic and peer-oriented learning styles than females, while females tended to be more auditory learners, self-motivated, persistent, and responsible than male learners. This implies that fathers may benefit from participation with other fathers and interventions that focus on interaction/action as opposed to communication/relatedness.

In addition, females may use more words and have better listening skills, but along with higher scores in math and science, males obtain route knowledge from landmarks more rapidly and demonstrate greater spatial cognition than females (Cutmore, Hine, Maberly, Langford, & Hawgood, 2000; Driscoll, Hamilton, Yeo, Brooks, & Sutherland, 2005). According to the research conducted by Driscoll et al. (2005), the latter may be in part due to circulating testosterone levels. Whatever the reason behind the different learning styles, recognizing and addressing these gender differences is imperative and has implications for future research about how best to help fathers intervene to enhance communication and socialization in their children with ASD.

Fathers as Effective Interveners

Understanding the influence of male learning principles and recognizing the important roles that fathers can have in child development lead to further examination of strategies that can be considered to increase father involvement. Play-based interventions may be particularly appealing to fathers and serve as a means of empowering them to intervene in ways that promote child socialization and language development. In fact, Flippin and Crasis (2011) note in their critical review that fathers may be uniquely suited to enhance play skills. Lamb (1981) also note that there is ample evidence that fathers tend to specialize in play whereas mothers focus on caretaking and nurturance. They further assert that boisterous, stimulating, and emotionally arousing play is more a characteristic of father-child play and is especially “salient” for the children (Lamb, Frodi, Hwang, & Frodi, 1983).

Acquiring strategies that promote language development is also particularly important for fathers who typically spend less time with their children than mothers and thus may be less familiar with their children’s language competencies. This may result in fathers using more directives, wh-questions, and imperatives that can challenge young children (Lamb & Tamis-Lemonda, 2004). We found in our work that children with ASD often have difficulty processing wh-questions and can become very frustrated by directives and imperatives that they may not fully understand or be given adequate time to respond to.

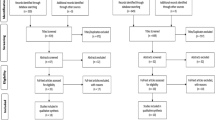

We considered these findings related to fathers, play, and language development when we developed and tested our in-home father intervention for promoting socialization and language development in young children with ASD (Elder et al., 2010). The intervention targeted four skills: following the child’s lead (rather than directing the child), imitating the child with much animation, commenting on the child’s actions, and waiting expectantly for child responses. We video-recorded all play sessions with fathers and evaluated the father’s acquisition of the target skills twice a week for 12 weeks. We found that playbacks of video recordings and video-recorded examples of other fathers applying the target skills were particularly well-received by fathers. In addition to video playbacks, graphs were used to illustrate progress in the fathers’ learned behaviors and child outcomes. This concrete visual evidence was of particular interest to the fathers in this study—a finding that concurs with information found in the studies cited above. Indeed, the use of visual support such as graphs and video demonstrations may be more helpful than verbal explanations when working with fathers.

Results from 18 dyads showed significant increases in frequencies of fathers’ imitation with animation, expectant waiting, and commenting on the child. Child social initiating rates during play increased significantly as well as child nonspeech vocalizations. Mothers, who received their training from the fathers rather than our team, showed significant increases in frequencies of imitation with animation, expectant waiting, and following the child’s lead. Child behaviors had similar results for father and mother sessions. Results from this as well as an earlier NIH-funded father-focused study (Elder, Valcante, Yarandi, White, & Elder, 2005) demonstrated that fathers could help their children with ASD improve in the areas of language and social skills through naturally occurring play interactions (Elder et al., 2010).

In addition to these quantitative findings, we also made other important observations. For example, one child with ASD responded to his father’s imitations and roughhouse play by making eye contact and saying “Daddy” to the father for the first time. This experience led to the father stating that he felt the intervention was effective and that he would engage in the target skills on a regular basis with his child. In other clinical experiences, we have observed that when fathers feel that what they do is effective, they are more likely to co-parent, which can lessen the maternal workload and stress and increase family cohesion. Further, Allen and Daly (2007) reported that higher levels of father involvement in general were associated with a variety of positive outcomes for children with autism, including improved cognitive development and physical health.

We gained additional insight about fathers by adding a qualitative arm to our in-home study (Donaldson, Elder, Self, & Christie, 2011). Through this work, we were able to more fully describe fathers’ perceptions of their parental roles, relationships with their children with ASD, and participation in the in-home training program. In-depth semi-structured interviews with ten fathers were conducted at home, video-recorded, transcribed, and reviewed for common themes and significant statements. We identified several common themes that inform the current discussion related to empowering fathers. These themes included the importance of accepting the diagnosis, sharing time with the child, having a close relationship, and concerns and hope for the future. We also noted that communication between fathers and their children appeared to be the key to what fathers considered to be a more meaningful relationship even if the child was predominantly nonverbal. These fathers reported other ways of effective communicating including more time spent playing or just being with the child either at home or during outside activities.

Instilling Hope through Empowerment

We also found that trained and empowered fathers expressed a more positive outlook and hope for the future. The importance of hope is well-documented in the literature, and there are indications that parental optimism may have effects that extend beyond the psychological well-being of the parent (Ekas, Lickenhrock, & Whitman, 2010). For example, Durand (2001) studied how parental optimism/pessimism impacts the development of later challenging behaviors in young children with cognitive and/or developmental disabilities. This longitudinal study measured a number of parental variables that were thought to predict the development of severe behavior problems. They determined that the best predictor was a measure of parental optimism; that is, parents who had less confidence in their ability to influence their children’s behavior by age 3 were more likely to have children with difficult behaviors later in life.

This finding leads to several other considerations that warrant further investigation. First, there is the possibility that parents with more confidence may have better natural skills at interacting with children with ASD. Second, parents with more confidence may simply try harder to engage with their child and are likely to reach out to receive the appropriate professional training for their child. Third, there is the likely notion that it may be a combination of these.

Recommendations

Findings from the literature related to fathers and male learning, father intervention research, and anecdotal accounts from clinical practice suggest several recommendations for clinical practice and highlight areas needing future research to enhance our understanding of fathers and the importance of their parental roles (Table 16.1).

Conclusion

As discussed, recent societal shifts toward more active father involvement and co-parenting indicate an urgent need to further understand the father’s role in child development and how to enhance healthy father-child interactions. This is particularly true for fathers of children with ASD who are rarely included in reported parent training studies, and yet preliminary studies indicate that these fathers may be very effective interveners. Clearly, more research is needed since educated fathers are well-positioned to assume critical roles for improving the quality of life for their children with ASD and subsequently their entire families.

References

Allen, S., & Daly, K. (2007). The effects of father involvement: An updated research summary of evidence. Retrieved from the Father Involvement Research Alliance (FIRA) website: http://www.fira.ca/cms/documents/29/Effects_of_Father_Involvement.pdf

Bendixen, R., Elder, J., Donaldson, S., Kairella, J., Valcante, G., & Ferdig, R. E. (2011). Effects of a father-based in-home intervention on perceived stress and family dynamics in parents of children with autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(6), 679.

Cutmore, T., Hine, T., Maberly, K., Langford, N., & Hawgood, G. (2000). International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 53, 223–249.

Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278–1291.

Doherty, W. J., Kouneski, E. F., & Erickson, M. F. (1998). Responsible fathering: An overview and conceptual framework. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60, 277–292.

Donaldson, S., Elder, J., Self, E., & Christie, M. (2011). Fathers’ perceptions of their roles during in-home training for children with autism. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 24(2011), 200–207.

Driscoll, I., Hamilton, D., Yeo, R., Brooks, W., & Sutherland, R. (2005). Virtual navigation in humans: The impact of age, sex and hormones on place learning. Hormones and Behavior, 47(3), 326–335.

Durand, V. M. (2001). Future directions for children and adolescents with mental retardation. Behavior Therapy, 32, 633–650.

Ekas, N. V., Lickenbrock, D. M., & Whitman, T. L. (2010). Optimism, social support, and Well-being in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(10), 1274–1284.

Elder, J.H., Donaldson, S.O., Kairalla, J., Valcante, G., Bendixen, R., Ferdig, R., Self, E., Walker, J., Palau, C., & Serrano, M. (2010). In-home training for fathers of children with autism: A follow up study and evaluation of four individual training components. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(3), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-010-9387-2. PMCID: 3087101.

Elder, J. H., Valcante, G., Yarandi, H., White, D., & Elder, T. (2005). Evaluating in-home training for fathers of children with autism using single-subject experimentation and group analysis methods. Nursing Research, 54(1), 22–32.

Flippin, M., & Crais, E. R. (2011). The need for more effective father involvement in early autism intervention: A systematic review and recommendations. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(1), 24–50.

Flourini, E., & Buchanan, A. (2003). The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. Journal of Adolescence, 26, 63–78.

Hall, H. R., & Graff, J. C. (2011). The relationships among adaptive behaviors of children with autism, family support, parenting stress, and coping. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 34, 4–25 https://doi.org/10.3109/01460862.2011.555270

Hastings, R. P., Kovshoff, H., Ward, N. J., Espinosa, F., Brown, T., & Remington, B. (2005). Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 635–644.

Honigsfeld, A., & Dunn, R. (2003). High school male and female learning-style similarities and differences in diverse nations. Journal of Educational Research, 96(4), 195–205.

Hunter, D., Gambell, T., & Randhawa, B. (2005). Gender gaps in group listening and speaking: Issues in social constructivist approaches to teaching and learning. Education Review, 57(3), 329–355.

Ingersoll, B., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2011). The relationship between the broader autism phenotype, child severity, and stress and depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 337–344.

Kayfitz, A., Gragg, M., & Orr, R. R. (2010). Positive experiences of mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23, 337–343 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00539.x

Kubler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. New York, NY: MacMillan.

Lamb (1976). The role of the father in child development. New York: Wiley.

Lamb, M. E. (1981). Father and child development: An integrative overview. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (3rd ed., pp. 1–70). New York, NY: Wiley.

Lamb, M. E., Frodi, M., Hwang, C. P., & Frodi, A. M. (1983). Effects of paternal involvement on infant preferences for mothers and fathers. Child Development, 54, 450–452.

Lamb, M. E., & Tamis-Lemonda, C. (2004). The role of the father: An introduction. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 1–31). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Little, L. (2013). Differences in stress and coping for mothers and fathers of children with Asperger’s syndrome and nonverbal learning disorders. Pediatric Nursing, 28(6), 565–570.

McBride, B. A., & Lutz, M. M. (2004). Intervention: Changing the nature and extent of father involvement. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 446–475). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Pleck, J. H. (1982). Husbands’ and wives’ paid work, and adjustment. Wellesley, MA: Wellesley College Center for Research on Women.

Pleck, J. H., & Masciadrelli, B. P. (2004). Paternal involvement by U.S. residential fathers: Levels, sources and consequences. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (4th ed., pp. 222–271). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Ross, E. K.-R., & Kessler, D. (2007). Finding the meaning of grief through the five stages of loss. New York, NY: Scribner.

Stryker, S. (1991). Exploring the relevance of social cognition for the relationship of self and society: Linking the cognitive perspective and identity theory. In J. A. Howard & P. L. Callero (Eds.), The self-society dynamic: Cognition, emotion, and action (pp. 19–41). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Elder, J.H. (2018). Engaging Fathers in the Care of Young Children with Autism. In: Siller, M., Morgan, L. (eds) Handbook of Parent-Implemented Interventions for Very Young Children with Autism. Autism and Child Psychopathology Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90994-3_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90994-3_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-90992-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-90994-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)