Abstract

There are systematic parallels between the nominal and verbal domains of Hungarian in their inflectional paradigms. Seeking a descriptively and explanatorily adequate syntactic analysis of these morphological parallels, this paper presents an integrated approach to Hungarian possessive and definiteness marking, with clitics as the key players. The marker -JA (the ‘possessive morpheme’ in the noun phrase and the ‘definiteness agreement marker’ in present tense clauses) is traced back to an object clitic in Proto-Uralic, and analysed in the same terms in present-day Hungarian. The distribution of -JA across the nominal and present-tense verbal paradigms is derived from specific structural representations of person and the alienable/inalienable possession distinction; the absence of -JA from the past tense verbal paradigm is made to fall out from an analysis of Hungarian past tense forms as inalienably possessed inflected participles.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The nominal and verbal inflectional paradigms in Hungarian show systematic parallels. For the first and second person singular, the morphological parallelism is perfect. In the third person singular, with nouns like anyag ‘fabric’ and keret ‘frame’, which can have alienable as well as inalienable possessors, we find two inflectional possibilities: a form matching or containing the inflection also found in the present tense definite verbal paradigm; or a form lacking the -j (vocalised to -i with front-vowel verbal stems), corresponding to the inflection found in the past tense verbal paradigm.

In the nominal system, for nouns that in principle accept either form (such as anyag ‘fabric’ and keret ‘frame’), the -j-less form signals inalienable possession: the fabric that something is made out of; the frame that inalienably belongs to a person (i.e., his/her body) or to a picture (i.e., a picture frame). By contrast, the form with -j, in (1a) and (2a), marks an alienable possession relation between the fabric or frame and its possessor—the piece of fabric that is in the possession of a seamstress or tailor; or a pictureless frame that is among someone’s earthly belongings.

A descriptively and explanatorily adequate analysis ought to be able to capture the morphological parallels seen in (1)–(2) in an optimally simple way that informs the general theoretical outlook on the status and function of what is usually called ‘agreement marking’ in the grammar. I will start out in this paper by looking in detail at the marker -JA, which will lead us to an account.

2 The Marker -JA in the Verbal System

The morphological marker -JAFootnote 1 occurs in two apparently unrelated contexts, doing apparently unrelated things. In possessed noun phrases, it marks alienable (vs. inalienable) possession. In the present-tense verbal inflection paradigm, it is the marker of the definiteness of the object.

The distribution of -JA in both contexts reveals a sensitivity to person: -JA does not co-occur with the markers -m (1sg) and -d (2sg): see (3) and (4). We can trace this back to the proto-language from which Hungarian developed.

2.1 Diachrony

Two historical facts are relevant to the synchronic picture emerging from (1)–(4).

In Proto-Uralic (the common ancestor of all Finno-Ugric languages, including Hungarian), the existence of two verb forms covarying with the definiteness of the object was exclusive to the third person. The reconstructed singular paradigms of the verbal inflectional suffixes and personal pronouns of Proto-Uralic in (6) illustrate this (see Hajdú 1972:44; the possessive markers have the same ancestry).

Hajdú (1972:44) states explicitly that the reconstructed Proto-Uralic marker se, the ancestor of the def marker -JA, ‘was originally a pronoun with the value of the Accusative’. I take this to mean that Proto-Uralic se was an object clitic. This object clitic freely combined with the marker of the third person subject, which was itself silent (see ‘3indef’ in (6)), to deliver ‘definite agreement’: the combination of a third person def object clitic and a third person subject marker is se + ∅.

But already in the proto-language, se did not combine with the first and second person subject markers:

As Hajdú (1972:43) noted, and as is illustrated in (6), these first and second person subject markers have a perfectly transparent relationship with the first and second person singular pronouns of Proto-Uralic. In line with Preminger’s (2014) perspective on clitics, I take this to indicate that the Proto-Uralic markers for first person (-m) and second person (-t) are subject clitics. When we now combine this with the conclusion that se is an object clitic, the generalisation in (8) can be recast as a clitic co-occurrence restriction similar to the kind found in many languages in the realm of ditransitive constructions—the Person Case Constraint (PCC; Bonet 1991).

In a typical PCC case like (9), from French (see Perlmutter 1971), if the structure contains two object clitics, and one of them is third person and the other is not, then the third person clitic has to be the direct object: when it is the indirect object, as in (9b), the output is ungrammatical.

Anagnostopoulou (2003) argues that the direct-object clitic is launched from a position structurally lower than the indirect-object clitic. Bearing this in mind, the descriptive generalisation presented by (9) can be stated in the following terms: if the structurally lower argument is a first or second person clitic and the structurally higher argument (the indirect object in (9)) is a clitic that is not marked for person (‘third person is non-person’; Benveniste 1971), there is no grammatical output.

We can understand this if clitics marked for first or second person (i.e., participant clitics) need to associate with a functional head in the structure outside the VP that is dedicated specifically to person. Let us call this functional head ‘π’. If in the structure in (10) (on the ‘relator’, see den Dikken 2006) the first or second person clitic is the indirect object, a perfectly local association between the participant clitic and π can be established, without any interference from the direct object, which is structurally lower. But now imagine that the participant clitic is the direct object, and that the occupant of the indirect object position is likewise a clitic but one that is not marked for person (i.e., ‘third person’). We then get a situation in which π has a clitic in its local environment (viz., the indirect object clitic) but one that, because of its lack of a person feature, cannot serve as a goal for π—it is a possible goal for π but, due to its featural defectiveness, not an actual one.

Rezac (2008) and Preminger (2014) argue that when the indirect object is a third person clitic and the direct object is a participant clitic, the structure in (10) presents an intervention effect: the third person indirect-object clitic prevents π from associating with the direct-object clitic.

How can this help us understand the Proto-Uralic generalisation in (8)? We have already determined that the first and second person markers -m and -t are subject clitics. We have also argued that Proto-Uralic se is an object clitic. We know from (6) that the object clitic se specifically represents definite objects. The one thing we now need to add into this mix to get a complete account is that se, because of its specificity, obligatorily shifts to a position outside VP that is structurally higher than the base position of the subject, as depicted in (11).

We now derive the fact that whenever the subject is a first or second person clitic (which wants association with π), the direct object cannot be the third person clitic se: its presence in (11) would obstruct the necessary relation between π and the subject clitic, as an intervention effect. A grammatical result cannot emerge, in the presence of a first or second person subject clitic, if the object is the clitic se. For third person definite objects, this means that, when a first or second person subject clitic occurs, they cannot be doubled by an object clitic: when no object clitic is used, no intervention effect manifests itself because, even if the object does shift to the edge of vP, it still will not be a possible goal for π, which in Proto-Uralic (as in Romance) is specialised for clitics: there is no person agreement for non-clitic objects in Proto-Uralic.

Thus, if we follow an approach to Person Case Constraint effects such as (9b) along the lines of Rezac (2008) and Preminger (2014), we can make (8) follow from the clitic status of both se and the first and second person subject markers, in conjunction with the hypothesis that the object clitic se, whenever present, is launched from the object shift position, closer to the person probe π than the subject’s base position. The result of this clitic co-occurrence restriction is that there can be no def/indef distinction in the presence of a first or second person subject in Proto-Uralic: def-marking (i.e., the occurrence of the object clitic se) is consistently impossible in this context.

2.2 Synchrony

In present-day Hungarian, -JA (the successor of se) still does not mix with the first and second person subject markers -m and -d (the transparent heirs to Proto-Uralic -m and -t): (12). What this suggests is that present-day Hungarian -JA, the so-called ‘definiteness marker’ in the verbal paradigm, is still an object clitic, and that -m and -d continue to behave as subject clitics. If so, the fact that 1sg -m and 2sg -d do not combine with -JA follows from (11), carried over to Modern Hungarian.

Regarding the status of -JA in Modern Hungarian, Coppock and Wechsler (2012) state that ‘there is a consensus… that the -ja found in the third person singular of the objective conjugation can be traced back to a third person object pronoun, which Hajdú (1972) reconstructs as *se’.Footnote 2 For -m and -d, my hypothesis that, synchronically as well as historically, they are subject clitics makes me side with Trommer (2003) in taking -m/-d to only encode the subject’s φ-features, not definiteness as well. Definiteness agreement is not morphologically encoded in the first and second person singular in Modern Hungarian any more than it was in Proto-Uralic. The fact that there is no definite/indefinite distinction in the first person singular in the past tense (see (13a)) thus represents the expected pattern for Modern Hungarian.

In the second person, the past tense does feature two discrete verbal forms for definite and indefinite agreement, as shown in (13b). And in the present tense, for both first and second person singular, there is a morphological distinction between definite and indefinite inflection as well: (14). Modern Hungarian has innovated non-clitic inflectional markers for first and second person singular in the indef agreement paradigm (-k and -sz/-l, resp.) to mark the definite/indefinite distinction (see Coppock and Wechsler 2012, and references cited there). I do not have space here to say anything about these inflectional markers. The only thing that matters for my purposes here is that they are resorted to precisely in contexts in which the clitic co-occurrence restriction in (8), dating back to Proto-Uralic, prevents the subject clitics -m and -d and the object clitic -JA from being used together. Proto-Uralic was satisfied to simply not mark the definiteness of the object on the inflected verb at all in such contexts. In an effort to systematise the marking of the (in)definiteness of the object on the verb, Hungarian created inflections for first and second person singular subjects alongside the clitics -m and -d. The latter continued to be used but became specialised for the definite paradigm.Footnote 3

3 The Marker -JA in the Nominal System

The marker -JA occurs not only as a marker of definiteness agreement in the verbal system (analysed in Sect. 2 as an object clitic) but also as a marker of mostly alienable possession in the nominal system.Footnote 4 In both contexts, its distribution is restricted: in neither does the marker co-occur with the first and second person singular markers, -m and -d. The data in (1) and (2), repeated here, will serve as a reminder.

Making the analysis of the verbal inflection paradigm developed in Sect. 2 carry over to the possessive paradigm requires two things: (a) a treatment of -m and -d as clitics and (b) an assimilation of -JA qua marker of alienable possession to -JA qua marker of the object’s definiteness—i.e., a treatment of possessive -JA as a clitic. As a first step towards achieving this goal, we need to investigate the syntax underlying possessive relations, which is the topic of Sect. 3.1.

3.1 A Structural Difference Between Alienable and Inalienable Possession Relations

In den Dikken (2015), I argue—based on the facts of a variety of typologically unrelated languages—that Universal Grammar makes a structural distinction between alienable and inalienable possession relations that exploits a key ingredient of den Dikken’s (2006) theory of predication: the idea that predication relations, while universally asymmetrical, are not inherently directional:

The predicate and its subject must always be related to one another with the aid of a mediator (called the relator); but as long as the relation between them is asymmetrical, the relative positions in the RP that are taken by the predicate and its subject are not predetermined: (15a, b) are both possible.

In den Dikken (2015), I extend the coverage of the hypothesis in (15) into the realm of possession. The proposal is that canonical predication is involved in alienable possession relations, while inalienable possession has a reverse predication structure as its underlier. This delivers (16):

3.2 The Marker -JA as a Clitic in the Possessed Noun Phrase

There are cogent reasons to want to pursue an analysis of the marker -JA that assimilates its verbal and nominal uses: not only are they homophonous, they also have identical distributions vis-à-vis the person of the subject or possessor—in both the definite agreement system and the possessed noun phrase, the marker systematically fails to co-occur with the first and second person singular markers, -m and -d. For the incompatibility of this marker with -m and -d in the verbal system, an account was put in place in Sect. 2 that can be traced back all the way to a clitic co-occurrence restriction in effect already in Proto-Uralic: (8). To get a purchase on the incompatibility of -JA with -m and -d in the possessed noun phrase, we would ideally link up to this account very directly.Footnote 5

To accomplish this, I will present a perspective on the morphological status and syntactic behaviour of the marker -JA in the Hungarian possessed noun phrase that assimilates it to the marker -JA in the definite verbal agreement system, and treats it as a clitic. The central claim of the analysis is that the possessum can include the clitic -JA, and that when it does, this clitic prevents a grammatical output from emerging when the possessor is first or second person, and in inalienable possession cases even when the possessor is third person.

Let us start with alienable possession constructions. In the syntax underlying alienable possession, given in (16a), the possessum is structurally higher than the possessor. When -JA appears in the possessum, and the possessor is the first or second person clitic -m/-d, -JA prevents the latter’s cliticisation to the immediately small-clause external person head π:

As in the verbal system, the presence of the clitic -JA in a structural position between π and the first or second person clitic -m/-d prevents π from forging the necessary link between itself and the person-marked clitic. The intervention effect that ensues is responsible for the ungrammaticality of the starred forms in (3a) and (4a) (repeated below), analogously to that of the starred forms in the b–examples, from the verbal system.

When the alienable possessor is the clitic -m or -d, therefore, -JA is prevented from occurring: its presence would result in (17), which the grammar rejects.

The clitic -JA does co-occur with the person markers -m and -d, however, in alienably possessed noun phrases whose the possessum is plural (marked by the possessive plural marker -i, bolded in (18) for easy spotting):

To understand this, we first need to get a grip on the plural marker -i, which occurs in two environments in present-day Hungarian: (a) possessed noun phrases whose possessum is plural (just illustrated), and (b) the first and second person plural pronouns, mi ‘we’ and ti ‘youPL’. What I would like to propose as a way to unite these two apparently unrelated uses of -i is the following. Assume (with Bartos 1999: Sect. 2.3, Dékány 2001:248, and references there) that the first and second person plural pronouns of present-day Hungarian are associative plurals: ‘me/youSG and associate(s)’.Footnote 6 These associative plurals can be structurally represented such that -i takes as its complement a coordinative relator phrase containing the first/second person singular pronoun (m/t) and the projection of a silent noun (‘associate’): (19a). For the possessive plural examples in (18), too, the plural marker -i is structurally represented immediately outside a relator phrase—this time, the relator phrase in (17), within which the alienable possession relation is established. This is shown in (19b).Footnote 7

Unlike in (17), embedding the structure in (19b) under the person probe π to yield (17ʹ) does not lead to an intervention effect. This is because -JA, the clitic head of the possessum, cliticises to -i prior to the introduction of π: by the time π is merged, -JA has already found its host and has consequently been deactivated. So in (17ʹ), π can probe straight past -JA and reach its intended goal (the person clitic in the complement of the relator head) unobstructed.

When the possessor is not a person-marked clitic, the presence of -JA in the possessum presents no trouble: there is no person-marked element that seeks to associate with π; the presence of π is redundant, and therefore most likely not called upon at all. Since nothing prevents -JA from occurring, the output of an alienable possession construction with a possessor that is not the clitic -m or -d can safely include this marker.

Now let us turn to inalienable possession, whose syntax is based on (16b). Here, -JA cannot occur at all—regardless of the person specification of the possessor. The subject of a reverse predication structure originates in the complement position of the relator, below its predicate. For reasons that are still not very well understood, there is a broad generalisation that whenever the predicate is structurally higher than its subject, the latter cannot engage in any movement dependencies across its predicate. We see this, for instance, in (20b), a failed attempt to move the subject of the reverse predications in the a–example.

Given that movement of the subject is generally impossible when its predicate c-commands it, the possessum in (16b) (the subject of a reverse predication structure) is prevented from containing the clitic -JA, which, if present, would be prevented from cliticising. In inalienable possession, therefore, -JA cannot occur: its presence in the structure would make the derivation crash inevitably. In inalienably possessed noun phrases with a third person possessor, the only possessive marking that we get is the exponent of the relator—i.e., the vowel -a or -e (see den Dikken 2015 for discussion of the relator status of the possession marker), as in (21) (repeated from (1a) and (2a)).

We now have an account of the alienable/inalienable contrast regarding the distribution of the marker -JA (also recall fn. 4).Footnote 8

4 The Past Tense

In connection with the distribution of the marker -JA in the verbal definiteness agreement system, something needs to be said about the past tense paradigm, in which -JA systematically fails to occur, even in the definite conjugation:

The way in which I presented this fact in the paradigms in (1) and (2), in the introduction, may already have revealed to the reader how I would like to approach it. The relevant portions of the paradigms in (1) and (2), for the third person singular, are repeated in (23):

These paradigms draw an implicit connection between the absence of -JA in the inalienably possessed noun phrase and the absence of -JA in the past tense forms of the definite agreement paradigm. I want to make this connection explicit now, by arguing that the -a and -e that follow the past tense marker -t, in látta and szerette, are the exponents of the possessedness marker of possessed noun phrases, i.e., exponents of a relator head mediating a possession relation between a subject and a predicate.

The idea is that the Hungarian past tense forms are all built on a non-verbal base—they are inflected participles rather than verbs. The event denoted by the participial predicate is in the subject’s possession. Since the subject cannot possibly avoid possessing it (after all, whatever you may have done in the past will stick to you for the rest of your life), it is the subject’s inalienable possession—which explains the systematic absence of -JA from the past tense definite agreement paradigm, on a par with the fact that -JA does not occur in the paradigm of inalienably possessed noun phrases.

The hypothesis that the past tense forms have a non-verbal base in Hungarian is supported by the fact that this base is identical with the past participial (pptc) form, which clearly has a non-verbal distribution: past participles can occur as prenominal attributive modifiers:

The case for the non-verbality of the past tense base is strengthened by the fact that in the Hungarian counterfactual conditional construction the person/number-inflected past tense occurs in the complement of a form of the verb van ‘be’, as seen in (25). Here volna is invariant, showing no agreement with the notional subject of the sentence, which instead controls agreement on the form in volna’s complement. A sensible way to analyse this pattern is to say that volna does actually show agreement with its subject, but that its subject is not the notional subject of the conditional but instead the participial constituent formed by that subject and the past tense form of the verb—an inalienably possessed partipial phrase: what we have in (25) is best paraphrased as ‘if [my/your/his/her having seen it] were (the case)’.

To flesh out the structure of the core of the Hungarian ‘past tense’ construction, we need to first bring back from memory the syntax underlying inalienable possession constructions, given in (16b) and repeated here as (26a), with some morphological information put in. In the structure of the Hungarian past tense, the possessum is the inalienably possessed participial form of the verb; its possessor is the notional subject of the sentence, as in (26b).

The possessum in (26) cannot harbour the clitic -JA: the complement of the relator in a reverse predication structure is generally frozen, as discussed in Sect. 3; and the structure of the possessum is not large enough to provide a host for the clitic either. What we get inside the RP in (26b) is the suffix -a/e as the spell-out the relator that mediates the relationship of inalienable possession between the participial predicate and the subject, which does indeed show up throughout the past tense paradigm for both the indefinite and the definite conjugation.Footnote 9

But while the absence of -JA in the past tense paradigm matches the absence of -JA in inalienably possessed noun phrases, the person morphology of the past tense paradigm is not identical with that of the possessive DP, as a comparison of the paradigm of lát-t in the left-hand column of (27) and the paradigm of inalienably possessed anyag in the right-hand column shows.

Moreover, there is an important morphosyntactic difference between the past tense inflectional paradigm and that of possessed noun phrases, having to do with ‘anti-agreement’. In the possessed noun phrase, a caseless/nominative third person plural possessor never co-occurs with plural inflection on the possessum: (28a). In the past tense, on the other hand, plural agreement is obligatory, both in the indefinite and in the definite conjugation, as shown in (28b).

So the physical subject of the past tense construction is not, in the final analysis, the possessor of an inalienably possessed participial form of the verb. That the plural forms in the past tense definite paradigm for back-vowel stems in (22) (-uk, -átok and -ák) are identical with the corresponding forms in the present tense definite paradigm for back-vowel stems points in the same direction.

The subject of the past tense is not just the inalienable possessor of the participial phrase: it must also be represented outside the possessive structure in (26b), in a position where it can control agreement with a present tense finite verbal element. The way to do this, I suggest, is to introduce a verbalising light verb v outside the structure in (26b), as in (29).

The physical subject is base-generated in the matrix clause, introduced there by the light verb v, and controls a PRO inside the small clause. The v outside the small clause does not just verbalise the structure; it also allows the object of the possessed participle to check case—a technical possibility on the assumption that no barrier intervenes between v and the object. But recall that the object cannot be the clitic -JA because extraction from the possessum in an inalienable possession structure is impossible. So what we get is what we want: accusative case for the object; person inflection for the subject; and still no clitic -JA.

5 Conclusion

The pervasive parallels between the nominal and the verbal systems that we find in Hungarian informed this paper from the outset, with the syntax of clitics playing the central explanatory role in the analysis. It is my hope that this analysis, and the new light that it sheds on so-called definiteness agreement and the morphosyntax of clitics, will give rise to novel insight into the nominal and verbal systems and the connection between the two, well beyond the boundaries of Hungarian.

Notes

- 1.

Throughout this paper, I will represent the marker involved as -ja, with the capital ‘A’ being a cover for the harmonic value of the vowel (-a after back-vowel stems, -e after front vowel stems), and the capital ‘J’ as a cover for the glide -j and the vowel -i. The fact that, with front-vowel stems, -ja is pronounced -je in the nominal system and as -i in the verbal system has to do with the fact that, in possessives, there is always a vowel spelling out the relator head that mediates the predication relation between the possessor and the possessum—see Den Dikken (2015) for discussion.

- 2.

The fact that the past-tense forms show no high vowel or glide entails that the hypothesised object clitic -ja of present-day Hungarian is not tense-invariant. For Nevins (2011), tense invariance is a defining property of clitics. For Hungarian, however, the absence of tense invariance in the distribution of the clitic -ja is not an accidental gap: see Sect. 4 for an account of the Hungarian past tense that allows us to understand the absence of the -j from its paradigms.

- 3.

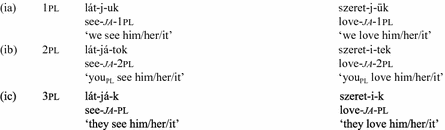

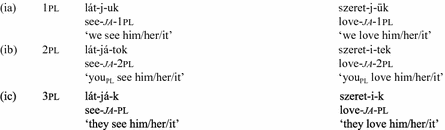

The constraint in (8) has carried over to Modern Hungarian only for the first and second person singular subject markers: the present tense plural forms -juk/jük in (ia) and -játok/itek in (ib) overtly contain the glide or high front vowel that represents the object clitic -ja, as do the forms -ják and -ik in (ic), for third person plural definite inflection.

This can be understood if the first and second person plural markers are not clitics. There is morphological support for this (along the lines of Preminger 2014). While first and second person singular -m and -d historically go back to the corresponding pronouns and still are transparently related to the first and second person singular pronouns, their plural counterparts in present-day Hungarian (first person -uk/ük and second person -tok/tek) show no synchronic surface relation to the corresponding nominative pronouns, mi and ti. (The second person plural forms do share a t—but the pronoun ti has the possessed plural marker -i, whereas the suffix -tok/tek has the default plural -k.) If they are not clitics but subject inflection markers, -uk/ük and -tok/tek do not seek to move from an argument position to the person head π (recall (11)). So no intervention effect arising from the presence of the object clitic -JA is expected in the first and second person plural. Only when the subject marker is a clitic (i.e., in the first and second person singular) is the marker -JA prevented from occurring, by the clitic co-occurrence restriction in (8), dating back to Proto-Uralic.

- 4.

The surface distribution -ja in possessive noun phrases is not just sensitive to the alienable/inalienable distinction. To a significant extent, the distribution of this marker is regulated by phonological considerations. The phonology can even cause -ja to occur in contexts in which the morphosyntax does not deliver it: inalienable possession constructions do include -ja whenever a phonotactic constraint forces it to occur. Following den Dikken (2015), the line that I take on this here is that the phonology co-opts an element that is available in the system, by analogical extension.

- 5.

The particular way in which den Dikken (2015) mobilises the structures in (16) to derive the distribution of the marker -ja in the Hungarian possessed noun phrase is unsuccessful in relating the marker -ja found in possessed noun phrases to the marker found in the definite agreement paradigm. It treats the -a of -ja as a relator, and the -j characteristic of alienable possession constructions as the exponent of the linker—a functional head outside the small clause (RP) in (16a) into whose specifier position the possessor raises in the course of the derivation, as shown in (i). With -a obligatorily raising to -j, and with the amalgamated marker -ja docking on to the possessum in the phonological component, the desired output for anyag-ja ‘his/her fabric (al.)’ and keret-je ‘his/her frame (al.)’ emerges.

- 6.

The fact that Hungarian says things like ‘we went to the movies with my wife’ in situations in which the speaker and his wife went to the movies together as a couple is compatible with this.

- 7.

Note that (19) allows for a simple descriptive generalisation regarding the distribution of the ‘special’ plural marker -i (as distinct from the ‘regular’ plural marker -k): -i occurs when the plural morpheme takes a relator phrase as its complement (i.e., in the associative plurals mi and ti, and in possessive plurals); -k occurs elsewhere. For the associative plural construction exemplified by János-ék ‘János and his entourage’, Dékány (2011:241–2) argues cogently that -ék is not the plural of the possessive anaphor -é ‘x’s one’ (which is -éi instead). A possible approach to -ék treats it as the concatenation of an unpossessed pronoun e and a local plural -k, with a silent relator linking the ék thus formed to János in an asyndetic coordination structure, analogous to the Afrikaans associative plural pa hulle ‘dad them’.

- 8.

In the verbal system of Modern Hungarian, the clitic co-occurrence restriction in (8) affects only the first and second person singular markers -m and -d: their plural counterparts co-occur with -ja, thanks to the fact that they are not clitics (recall fn. 3). But in the alienably possessed noun phrase, first and second person plural possessors resist -ja:

I pointed out in fn. 3 that the first and second person plural agreement markers in the definite verbal paradigm bear no morphological relationship with the corresponding personal pronouns. It was on this basis that I supported the conclusion that the first person plural marker in the definite verbal agreement paradigm of Modern Hungarian is not a clitic. It is probably significant in this connection that the marker for a first person plural possessor in Modern Hungarian (the -ünk of keretünk) does have a morphological connection with the pronoun: the nasal of the marker -ünk is historically identical with the nasal of the pronoun mi ‘we’. If we are to conclude on this basis (along the lines of Preminger 2014) that the marker -ünk is a plural-marked first person clitic, then the fact that it is incompatible with the clitic -JA will fall out along the lines of (17). Extending this line of thinking to the second person plural is not a straightforward matter, however: the -tek of keretetek ‘yourPL frame’ and the -tek of szeretitek ‘youPL love it’ look exactly the same; arguing for the clitic status of the former and the non-clitic status of the latter will therefore lack any transparent phonological support, and runs the risk of being a self-fulfilling prophecy.

- 9.

Except in the third person singular indefinite. Here exponence of the relator is probably suppressed in order to avoid syncretism between the definite and indefinite forms.

References

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bartos, H. 1999. Morfoszintaxis és interpretáció. A magyar inflexiós jelenségek szintaktikai háttere [Morphosyntax and interpretation. The syntactic background of Hungarian inflexional phenomena]. PhD disseration, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary.

Benveniste, Emile. 1971. Problems in general linguistics. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press (originally appeared in French in 1966; Paris: Gallimard).

Bonet, Eulàlia. 1991. Morphology after syntax: Pronominal clitics in romance languages. PhD dissertation, MIT.

Coppock, Elizabeth, and Stephen Wechsler. 2012. The objective conjugation in Hungarian: Agreement without phi-features. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 30: 699–740.

Dékány, É. 2011. A profile of the Hungarian DP. The interaction of lexicalization, agreement and linearization with the functional sequence. PhD dissertation, University of Tromsø, Norway.

den Dikken, Marcel. 2006. Relators and linkers: The syntax of predication, predicate inversion, and copulas. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

den Dikken, Marcel. 2015. The morphosyntax of (in)alienably possessed noun phrases: The Hungarian contribution. In Approaches to Hungarian, vol. 14, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, Balázs Surányi and Éva Dékány, 121–45. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hajdú, Péter. 1972. The origins of Hungarian. In The Hungarian language, ed. Loránd Benkő, and Samu Imre, 15–48. The Hague: Mouton.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29: 939–971.

Perlmutter, David. 1971. Deep and surface structure constraints in syntax. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rezac, Milan. 2008. The syntax of eccentric agreement: The Person case constraint and absolutive displacement in Basque. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26: 61–106.

Trommer, Jochen. 2003. Hungarian has no portmanteau agreement. In Approaches to Hungarian, vol. 9, ed. Péter Siptár, and Christopher Piñón, 283–302. Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

den Dikken, M. (2018). An Integrated Perspective on Hungarian Nominal and Verbal Inflection. In: Bartos, H., den Dikken, M., Bánréti, Z., Váradi, T. (eds) Boundaries Crossed, at the Interfaces of Morphosyntax, Phonology, Pragmatics and Semantics. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 94. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90710-9_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90710-9_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-90709-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-90710-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)