Abstract

Surgery plays an integral role and perhaps offers the only curative option in the management of hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies. Chemotherapy and radiation, either in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting, have further complemented the outcomes of radical surgery and play an important role in palliation. This chapter presents the principles of management of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cancers of the gall bladder and biliary tract and pancreatic cancer.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

3.1 Introduction

Surgery plays an integral role and perhaps offers the only curative option in the management of hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies. Chemotherapy and radiation, either in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting, have further complemented the outcomes of radical surgery and play an important role in palliation. This chapter presents the principles of management of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), cancers of the gall bladder and biliary tract and pancreatic cancer.

3.2 Management of HCC

Surgical resection forms the mainstay in the treatment of HCC. However, the majority of patients are inoperable at presentation either on account of tumour extent or underlying liver dysfunction.

Estimation of liver functional status by the Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification forms the backbone of estimation of liver functional reserve (Table 3.1).

There are various treatment options in the management of HCC as listed below. Decisions on treatment strategy are best taken on an individual basis through a multidisciplinary approach.

-

1.

Surgical resection

-

2.

Liver transplantation

-

3.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA)

-

4.

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE)

-

5.

Radioembolization

-

6.

Radiotherapy and stereotactic radiotherapy

-

7.

Systemic chemotherapy and targeted therapy

-

1.

Surgical Resection

Patients ideally suited for surgical resection are those who have disease limited to the liver, with no radiographic evidence of invasion of the liver vasculature, well-preserved liver function (Child’s A) and no portal hypertension [1,2,3]. Preoperative evaluation is best done with a multidisciplinary team to document adequate volume and function of the residual liver remnant. CT volumetry gives an accurate estimation of residual liver volume, and indocyanine green clearance is often used to estimate liver functional status in patients with borderline liver function. Long-term overall survival rates of ≥40% can be achieved with limited hepatic resections for small tumours (<5 cm) in patients with Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis [4].

-

2.

Liver Transplantation

For patients with localized HCC who are not candidates for resection, orthotopic liver transplantation is indicated in single lesions ≤5 cm, up to three separate lesions, not larger than 3 cm, no evidence of gross vascular invasion and no regional nodal or extrahepatic distant metastases. When these criteria are applied, a 4-year survival rate of 75% can be achieved. These criteria have become known as the Milan criteria and have been widely applied around the world in the selection of patients with HCC for liver transplantation [5].

-

3.

Radiofrequency Ablation

This technique uses high-frequency radio waves to ablate the tumour and is best suited for deep-seated small lesions (<3 cm) situated away from the hepatic hilum. The approach can be offered for tumours up to 5 cm and is associated with a local recurrence rate of 5–20%. Local ablation with RFA is recommended for patients who cannot undergo surgery or as a bridge to transplantation.

-

4.

TACE

Transarterial chemoembolization is indicated in patients with unresectable HCC that is multifocal or too large for percutaneous ablation, relatively preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A or B) and no extrahepatic disease, vascular invasion or portal vein thrombosis. TACE has been shown to provide a survival advantage over supportive care only in randomized trials [6, 7]. It is also used as a bridge to liver transplant.

-

5.

Radioembolization

Transarterial radioembolization (TARE) involves the transarterial administration of microspheres labelled with yttrium-90 (Y-90), which is a beta ray emitter having a half-life of 64.2 h and a maximum tumour penetration of 10 mm. These microspheres have a diameter of <60 μm and therefore have the ability to be shunted to the lungs or abdominal viscera. Elaborate pretreatment planning is required which includes mesenteric angiography, dosimetry planning and a transarterial macro-aggregated albumin study to look for pulmonary shunting. Transarterial radioembolization is usually preferred in the setting of portal vein thrombosis as it is associated with less embolic events [8]. Data from retrospective studies also show a trend towards better downstaging prior to transplant.

-

6.

Radiotherapy and Stereotactic Radiotherapy

Although HCC is a radiosensitive tumour, it is located in an extremely radiosensitive organ . Three-dimensional conformal radiation (3D–CRT) and stereotactic body radiotherapy techniques deliver higher doses of radiation to the tumour with less liver toxicity as compared to conventional radiotherapy. There is a lack of consensus as to appropriate indications for RT in patients with HCC. However, 3D–CRT or SBRT is a reasonable option for selected patients who are being considered for other local treatment modalities and have no extrahepatic disease, limited tumour burden and relatively preserved liver function (Child-Pugh class A or early class B).

-

7.

Systemic Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy

Hepatocellular carcinoma is a relatively chemotherapy-refractory tumour. Although data suggests some antitumour activity of a number of chemotherapeutic agents, their use is preferable within the context of a clinical trial. Sorafenib is an oral multikinase inhibitor that has shown activity in HCC. In 2007, it was approved for treatment of unresectable HCC by the United States FDA. This was based on data from randomized trials [9, 10] which showed a modest improvement in overall survival with sorafenib. Presently, sorafenib can be recommended in unresectable HCC in Child’s A and in a select group of Child’s B patients.

3.3 Management of Cancers of the Gall Bladder and Bile Duct

3.3.1 Surgery: Gall Bladder Cancer

Surgical resection offers the only potentially curative therapy for gall bladder cancer [11]. Surgery is indicated in Stage 0–II, i.e. Tis, T1, T2, N0 where it may be curative. Periaortic, pericaval, superior mesenteric artery and/or coeliac lymph node involvement (i.e. N2 disease) has a prognosis similar to patients with distant metastasis. This group constitutes unresectable disease (Table 3.2).

For T1a tumours, i.e. invading the lamina propria without muscular layer involvement, a simple cholecystectomy is adequate and offers cure rates of 73–100% [12, 13]. Patients diagnosed with incidental T1a gall bladder carcinoma after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy do not require re-resection as it does not offer any survival advantage [14].

Lymph node metastasis occurs in 15 and 62% of patients with T1b and T2 tumours, respectively [15, 16]. These patients benefit from extended or radical cholecystectomy which involves resection of the gall bladder with an en masse liver wedge resection and periportal lymphadenectomy. An intraoperative frozen section of the cystic duct margin is mandatory. Failure to achieve a negative margin at the cystic duct or frank involvement of the extrahepatic bile duct warrants an extrahepatic biliary tract excision with hepaticojejunostomy. An incidental diagnosis of T1b/T2 gall bladder cancer after simple cholecystectomy warrants a re-resection or revision radical cholecystectomy.

Stage III and Stage IVa, i.e. tumours involving adjacent organs like the stomach, duodenum colon, pancreas and the extrahepatic biliary tree, may be resectable in a selected group of patients. Surgery in this situation entails en masse resection of the involved organs and is best reserved for the fit patient at a high volume centre. Although prognosis remains guarded for this group of patients, retrospective series report favourable survival for these patients if an R0 resection can be achieved [17, 18]. However, the majority of Stage IVa tumours have involvement of the hepatic artery or portal vein rendering them unresectable. There is no role for debulking surgery; surgical exploration should only be undertaken if an R0 resection is feasible.

3.3.2 Surgery: Cholangiocarcinoma

Although surgery offers the only option for long-term control of cholangiocarcinoma, the 5-year survival rates are very poor, especially for node-positive disease even if an R0 resection is achieved. Resectability rates depend not only on tumour location but equally on the available surgical expertise as these are very specialized surgical procedures. Resectability rates for distal, intrahepatic and perihilar lesions have been reported as 91%, 60% and 56%, respectively [19].

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are managed by a formal hepatic resection and distal cholangiocarcinomas are resected with a pancreaticoduodenectomy. Perihilar tumours are the most surgically challenging. Even at high volume centres, resectability rates are less than 50%. Resection of the extrahepatic bile ducts alone leads to high rates of local recurrence either at the confluence of the hepatic ducts or at the caudate lobe branches. Addition of a hepatectomy with a caudate lobectomy improves outcomes [20, 21]. The type of surgical resection depends on the Bismuth subtype. For type I and II tumours, the procedure involves an en bloc resection of the extrahepatic ducts (with a 5–10 mm margin) with the gall bladder, regional lymphadenectomy and hepaticojejunostomy. A hepatic lobectomy is often required to achieve adequate margins on the bile ducts. Type III lesions usually require an additional lobectomy or trisectionectomy. As the caudate lobe branches are frequently involved in type II and III tumours, most centres recommend a caudate lobectomy in these patients. Extended resections involving the portal vein and/or multiple hepatic resections can be offered for the select few with type III and IV tumours at centres of excellence [22].

3.3.3 Adjuvant Therapy: Gall Bladder Cancer

T3 and/or node-positive gall bladder cancer is associated with poor survival outcomes even if an R0 resection is achieved. This suggests a role for adjuvant chemotherapy/radiation therapy. High quality data for adjuvant chemotherapy in gall bladder cancer is scarce, and hence participation in clinical trials is recommended.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for tumours ≥T2, node-positive disease and/or margin-positive resection. Generally, 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended using gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or a combination of both. Alternatively, 5-FU based chemoradiotherapy along with systemic chemotherapy is another acceptable option [23]. This regimen may be particularly beneficial for patient with margin-positive resection where systemic chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy is recommended.

3.3.4 Adjuvant Therapy: Cholangiocarcinoma

The evidence to support the routine administration of adjuvant therapy in resected cholangiocarcinoma is scarce, leading to a variety of available options in different patient groups.

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with a margin negative resection and no residual disease can be observed. Adjuvant chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, re-resection (if feasible) and ablation are acceptable options for margin-positive intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma resected with negative margins and negative nodes may be observed. Alternatively some centres recommend adjuvant chemoradiotherapy or systemic chemotherapy for these patients. Margin-positive resections may benefit from adjuvant chemoradiation followed by systemic chemotherapy, and node-positive disease warrants adjuvant systemic chemotherapy. Wherever applicable, systemic chemotherapy for cholangiocarcinoma is either fluoropyrimidine or gemcitabine based.

3.3.5 Unresectable Disease: Gall Bladder Cancer and Cholangiocarcinoma

The management of locally advanced and unresectable carcinoma of the gall bladder and bile ducts is essentially palliative barring a few exceptions. The goals of management of these patients are relieving of obstructive jaundice, pain relief and prolongation of life. Jaundice is effectively palliated with self-expanding metallic stents placed within the occluded bile ducts either via percutaneous, transhepatic or endoscopic route. In patients of good performance status, systemic chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy or a combination of both are acceptable options. These patients are at high risk to develop metastatic disease; therefore, a treatment regimen beginning with systemic chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy for the patients with good response and absence of metastatic disease is probably the most appropriate. Palliative chemotherapy (gemcitabine/cisplatin/fluoropyrimidine based) remains the only option for fit patients with metastatic disease.

3.4 Management of Pancreatic Cancer

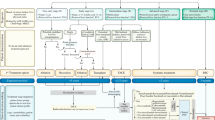

Only 15–20% of patients with pancreatic cancer are resectable at initial presentation. Key to the surgical management of pancreatic cancer is the initial classification of pancreatic tumours into resectable, borderline resettable and unresectable disease. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has defined borderline resectable and unresectable pancreatic cancer for tumours at different locations in the gland (Table 3.3).

The choice of surgical procedure depends on tumour location. Tumours in the pancreatic head and periampullary region are resected with a pancreaticoduodenectomy. A pylorus-preserving procedure is preferred wherever feasible as it leads to better functional outcomes without compromise on oncological adequacy [24]. A pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy will remove the entire duodenum (sparing the first 3–4 cm distal to the pylorus), the pancreatic head, uncinate process, proximal jejunum and peripancreatic and hepatoduodenal lymph nodes. Reconstruction is achieved with either a pancreaticogastrostomy or pancreaticojejunostomy, a hepaticojejunostomy and a duodenojejunostomy.

Patients presenting with obstructive jaundice and with either bilirubin above 20 mg/dL or with signs of cholangitis or in those in whom surgery will be delayed for more than 2 weeks undergo preoperative biliary drainage either endoscopically with endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreaticography (ERCP) and biliary stenting or via the percutaneous transhepatic approach. Preoperative biliary drainage while associated with a higher incidence of postoperative complications [25] may be beneficial in this select group of patients.

Tumours in the body and tail of the pancreas are best managed with a subtotal or distal pancreatectomy with or without a splenectomy. Rarely a total pancreatectomy is necessary to surgically extirpate disease diffusely involving the entire gland.

Neoadjuvant therapy is the first line of management for borderline resectable tumours. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (gemcitabine/fluoropyrimidine based), fluoropyrimidine-based chemoradiotherapy or both are acceptable options. A large proportion of borderline resectable tumours undergo R0 resection following neoadjuvant therapy with encouraging outcomes [26, 27].

Unresectable but non-metastatic pancreatic cancer is treated with initial chemotherapy (gemcitabine/nabpaclitaxel/FOLFIRINOX (5-FU + leucovorin + irinotecan + oxaliplatin)) followed either by fluoropyrimidine-based chemoradiation or further chemotherapy to maximal response.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for all patients following pancreatic resection [28, 29]. Gemcitabine with or without capecitabine for a duration of 6 months after recovery from surgery is the recommended protocol. Patients with node-positive disease and/or margin-positive resections may receive additional chemoradiotherapy following adjuvant chemotherapy [29].

Key Points

-

Decisions on treatment strategy are best taken on an individual basis through a multidisciplinary approach.

-

Surgery plays an integral role and perhaps offers the only curative option in the management of hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancies.

-

Surgical resection forms the mainstay in the treatment of HCC. However, the majority of patients are inoperable at presentation.

-

Radiofrequency ablation in HCC is best suited for deep-seated small lesions (<3 cm) situated away from the hepatic hilum. Local ablation with RFA is recommended for patients who cannot undergo surgery or as a bridge to transplantation.

-

TACE is indicated in patients with unresectable HCC that is multifocal or too large for percutaneous ablation, relatively preserved liver function (Child-Pugh A or B) and no extrahepatic disease, vascular invasion or portal vein thrombosis.

-

Adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for gall bladder tumours ≥T2, node-positive disease and/or margin-positive resection.

-

The management of locally advanced and unresectable carcinoma of the gall bladder and bile ducts is essentially palliative barring a few exceptions.

-

Only 15–20% of patients with pancreatic cancer are resectable at initial presentation. The choice of surgical procedure depends on tumour location. Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy is the procedure of choice for resectable tumours in the pancreatic head and uncinate process.

-

Tumours in the body and tail of the pancreas are best managed with a subtotal or distal pancreatectomy with or without a splenectomy.

-

Adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for all patients following pancreatic resection.

References

Bruix J. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1997;25:259.

Vauthey JN, Klimstra D, Franceschi D, et al. Factors affecting long-term outcome after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1995;169:28.

Bruix J, Castells A, Bosch J, et al. Surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: prognostic value of preoperative portal pressure. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1018.

Roayaie S, Obeidat K, Sposito C, et al. Resection of hepatocellular cancer ≤2cm: results from two western centers. Hepatology. 2013;57:1426.

Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patient with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693.

Lo CN, Ngan H, Tsa WK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164.

Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734.

Salem R, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, et al. Radioembolisation for hepatocellular carcinoma using yttrium-90 microspheres: a comprehensive report of long-term outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:52.

Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–90.

Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34.

Jayaraman S, Jarnagin WR. Management of gall bladder cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:331.

Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, et al. Early carcinoma of the gall bladder. Eur J Surg. 1992;158:545.

Wakai T, Shirai Y, Yokoyama N, et al. Early gall bladder carcinoma does not warrant radical resection. Br J Surg. 2001;88:675.

You DD, Lee HG, Paik Ky, et al. What is an adequate extent of resection for T1 gall bladder cancers? Ann Surg 2008;247:835.

Matsumoto Y, Fujii H, Aoyama H, et al. Surgical treatment of primary carcinoma of the gall bladder based on the histologic analysis of 48 surgical specimens. Am J Surg. 1992;163:239.

Shimada H, Endo I, Togo S, et al. The role of lymph node dissection in the treatment of gall bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:892.

Nimura Y, Hayakawa N, Kamiya J, et al. Hepatopancreatoduodenectomy for advanced carcinoma of the biliary tract. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38:170.

Nakamura S, Suzuki S, Konno H, et al. Outcome of extensive surgery for TNM stage IV carcinoma of the gall bladder. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2138.

Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar and distal tumours. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463.

Lim JH, Choi GH, Choi SH, et al. Liver resection for Bismuth type I and type II hilar cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2013;37:829.

Tan JW, Hu BS, Chu YJ et al. one-stage resection for Bismuth type IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma with high hilar resection and parenchyma-preserving strategies: a cohort study. World J Surg 2013;37:614.

Hemming AW, Mekeel K, Khanna A, et al. Portal vein resection in management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:604.

Ben-Josef E, Guthrie KA, El-Khoueiry AB, et al. SWOG S0890: a phase II intergroup trial of adjuvant capecitabine and gemcitabine followed by radiotherapy and concurrent capecitabine in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and gall bladder carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2617.

Diener MK, Knaebel HP, Heukaufer C, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus classical pancreaticoduodenectomy for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;245:187.

Van de Gaag NA, Rauws EA, van Eijck CH, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:129.

Barugola G, Partelli S, Crippa S, et al. Outcomes after resection of locally advanced or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer after neoadjuvant therapy. Am J Surg. 2012;203:132.

McClaine RJ, lowry AM, Sussman JJ, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy may lead to successful surgical resection and improved survival in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. HPB (Oxford) 2010;12:73.

Seufferlein T, Bachet JB, Van Cutsem E, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: ESMO-ESDO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii33.

Khorana AA, Mangu PB, Berlin J, et al. Potentially curable pancreatic cancer: American society of clinical oncology clinical practice guidelines. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2541.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

deSouza, A. (2018). Management of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Malignancies. In: Purandare, N., Shah, S. (eds) PET/CT in Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Malignancies. Clinicians’ Guides to Radionuclide Hybrid Imaging(). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60507-4_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60507-4_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-60506-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-60507-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)