Abstract

The chapter analyses John Lewis Partnership, an employee owned UK company which operates 42 John Lewis department stores across the UK, 328 Waitrose supermarkets, an online and catalogue business, a production unit, and a farm. The company is owned by a trust on behalf of all its 90,000 permanent staff, known as “Partners,” who have a say in the running of the business and receive a share of annual profits, which is usually a significant addition to their salary. Its Constitution states that “the happiness of its members” is the Partnership’s ultimate purpose, recognizing that such happiness depends on having a satisfying job in a successful business. It establishes a system of rights and responsibilities, which places on all Partners the obligation to work for the improvement of the business in the knowledge that they share the rewards of success. The Constitution defines mechanisms to provide for the management of the Partnership, with checks and balances to ensure accountability, transparency, and integrity. It established the representation of the co-owners on the Partnership Board through the election of Partners as Elected Directors.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

In 2016, the John Lewis Partnership (JLP) is an employee owned UK company which operates 46 John Lewis shops across the UK (32 department stores, 12 “John Lewis at home” and shops at St Pancras International Train Station and Heathrow Airport), 346 Waitrose supermarkets, an online and catalogue business, a production unit, and a farm. The company is owned by a trust on behalf of all its 91,500 permanent staff, known as “Partners,” who have a say in the running of the business and receive a share of annual profits, traditionally a significant addition to their salary. In 2015, the Company had annual gross sales of £10.92 billion.

In 2014, JLP celebrated 150 years in business. The company is beloved of Britain’s middle-class, who shop at its department stores and its Waitrose supermarket chain, and increasingly online. In 2015, it was named the most admired British company for honesty and trust in an Ipsos Mori survey. The brand is trusted because of its reputation for quality of service and value for money, including its policy of being “never knowingly undersold,” i.e., the store will refund the difference if a customer can find the identical product cheaper at another retailer (excluding online only retailers). Its unique governance structure has resulted in its becoming a talisman for corporate reform, inspiring the then UK’s Deputy Prime Minister in 2012, Nick Clegg, to discuss a “John Lewis economy” as the way forward for a role model for employee owned companies. It has also been called the “moral face of retailing” by consumers.

1 Background and History

John Lewis, the original founder, born in 1836 in the Somerset village of Shepton Mallet, was one of six children in a moderately affluent household, whose extended family owned various local businesses. However, the Industrial Revolution had caused the collapse of traditional businesses, so many people moved away from villages to bigger towns and cities. Having served various apprenticeships in a number of drapers in different Somerset towns, John Lewis was determined to break free and set up on his own. After a brief spell at a draper shop in Liverpool, where he was sacked for fighting, John set out to seek his fortune in London in 1856. This was opportune, as rising incomes and a growing middle-class opened aspirations for manufactured and crafted products and a desire to shop for fancy, exotic, and luxury goods.

In London, John eventually took a job with retailer Peter Robinson, where he specialized in buying silk, soon becoming a head buyer, the youngest in London. Within a short time, he was offered a partnership. However, this was not enough for his ambition, which was to make his own mark. Aged 28, in 1864, brimming with energy and self-confidence, financed by £600 from the life savings of his unmarried sisters, John bought 132 Oxford Street, now the site of JLP headquarters.

John had a hands-on style and ran his business with ultra control, prepared to fight (even physically) anyone who crossed him. His approach was to buy and sell cheap, yielding low-profit margins. He kept a prodigious amount of stock, buying nearly all the goods personally. The business grew slowly and steadily, although John steadfastly refused to advertise his business. One of his employers had taught him that “the art of pricing is to get profit where the public will not see it” (Glancey 2014: 14).

Staff wages and conditions were kept to a minimum, with long working hours. Shop assistants, mainly young women, were paid about £25 a year and many had to borrow to survive. They had to reach sales targets and were dismissed if they dared to marry. Given that the lift in the Oxford Street shop cost a penny farthing each time it went up or down, John could be seen standing by the lift gates, directing shoppers who looked fit to use the stairs.

John’s iron will was displayed in 1920, when staff took strike action, funded by the staff of rival companies, Harrods and Army & Navy Stores, and even by Queen Mary herself. However, John fired those on strike, declaring, “If I see them on their hands and knees, I shall not take them back” (Glancey 2014: 21). His determination to run his store as he, and only he, saw fit was demonstrated when he served three weeks in prison for contempt of court in 1903 in a legal dispute over what he was allowed or not allowed to do with his shop.

So, how did the Company make the journey from autocratic ownership and employer centered business practices to an employee centered cooperative? It starts with John Lewis’ own family. After a long relationship of almost 20 years with the love of his life, Eleanor “Nelly” Breeks, John was heartbroken when her parents refused to allow her to marry him, deeming him not grand enough for their daughter. When Nelly, who never married, died in 1903, he commissioned a monument to her memory.

John himself did not marry until 1884, when he was 48. He had two sons, John Spedan, born in 1885 and Oswald, born in 1887. Oswald took to the law and the army, while it was Spedan who joined the family business. However, father and son did not see eye to eye on how the business should be run. Spedan had picked up ideas about worker rights and democracy, and egalitarianism, in the sense that owners and managers should not be earning exorbitant multiples of what their employees were getting. He was inclined to renounce his wealth, while his father was determined to hold on to and augment it.

Spedan’s opportunity to put some of his ideas into practice came in 1914, when he was put in charge of Peter Jones, a department store in the fashionable Chelsea area, his father had purchased for cash in 1906. It was a way for John Lewis keep Spedan out of his way, and perhaps to turn around Peter Jones, which was loss making at the time. After giving the shop a facelift, Spedan set about improving worker conditions, with measures such as wage raises, coffee and tea breaks and clean toilets. Very significantly, practices which were to become the foundation of Partnership were established, with the creation of various representative staff committees. An innovation which continues to the present is the launch of a staff journal, the Gazette, where he and staff aired ideas and opinions. There was/is no censorship, and staff can post letters anonymously. Thus, the contrast in working conditions between John Lewis and Peter Jones could not have been greater, as were their trading fortunes. Unfortunately, John ended up having to bail out the Peter Jones shop in 1920.

The antagonism between father and son was somewhat alleviated when Spedan and his wife had a son in 1924, as John was captivated and delighted with both his daughter-in-law and grandson. Spedan was keen to unite the two businesses, but this was not possible while his father was still active. In 1926, Spedan’s brother Oswald, who was never interested in business, sold his share of the Company to Spedan, who had to take out a loan to pay for it. (Indeed, Oswald went on to serve as a Conservative MP for many years, returning to the Company, by then a Partnership, in 1951 as Director of Financial Operations, before retiring in 1963.) John Lewis never retired, only leaving the business on the day he died, June 8, 1928. “Spedan stepped into his shoes and with a spring in his step” (Glancey 2014: 25).

As the sole owner of the business, he moved to propagate his ideal of Partnership, which he had been mulling over the years. With the business valued at over £1 million, he formed the John Lewis Partnership, with a capital of £312,000, by means of the First Trust Settlement, in a document running to 268 pages. Profits were to be distributed to all Partners while Spedan would retain control, but receive no salary, fees or interest, living off a £1 million of noninterest paying loan stock repaid to him over a 30 year period. This sum would be devalued with inflation.

According to Spedan’s vision, “the Partnership was created wholly and solely to make the world a bit happier and a bit more decent” (JLP Annual Report and Accounts 2015: 15). Having established the Partnership, Spedan wanted to leave some clear guidelines for his successors, so that the values which had motivated him would not be eroded. These are embodied in a Constitution for the trust written by him. The Constitution states that “the happiness of its members” is the Partnership’s ultimate purpose, recognizing that such happiness depends on having a satisfying job in a successful business. It establishes a system of rights and responsibilities, which places on all Partners the obligation to work for the improvement of the business in the knowledge that they share the rewards of success. The second reason for the Constitution looks forward. Spedan Lewis was committed to establishing a “better form of business,” and the challenge for Partners of today is to prove that a business which is not driven by the demands of outside shareholders and which sets high standards of behavior can flourish in contemporary competitive conditions and, indeed, to demonstrate that adhering to these principles and rules even enables long-term outperformance over companies with conventional ownership structures.

Timing for establishing the Partnership could hardly have been worse, as the Great Depression starting in 1929 took hold, reducing consumer spending power. Nonetheless and encouragingly, many out-of-work university graduates were glad to find a job, even in “trade,” especially given the generous terms offered by JLP. From about 1933, Spedan began buying shops and departments stores outside London to forestall the threat of other growing multiples like Marks & Spencer (M&S), with its merchandise and grocery businesses. In 1937, Spedan decided to branch out into groceries, by buying the quality Waitrose chain. Meanwhile, Spedan had also been developing the Oxford Street flagship store by buying up adjacent properties, so by 1936, the store spanned two blocks. Sales more than doubled for JLP between 1932 and 1937, stretching the business, so no bonus was paid to Partners in 1938.

For all his generosity to his employees, Spedan was a benevolent autocrat, as a perfectionist who wanted to control events, not so different to his father. Throughout his business expansion of the 1930s, Spedan was quietly planning to give ownership and control of it to the Partners. But the outbreak of World War II was to present a challenge.

In September 1940, a German aerial flotilla of 268 bombers flew over London, hitting the length of Oxford Street, including the John Lewis shop, where some 200 people had taken protection in a makeshift shelter in its basement. Fortunately, there were no casualties. Meanwhile, upper crust customers were abandoning London for the safety of their country estates. During the course of the war, German bombs struck several other John Lewis shops in the provinces. There was much rebuilding work for John Lewis to do after the war. This was hampered by a shortage of fuel and raw materials.

On the positive side, Partners who had left to fight in the war were returning, and there was further recruitment. Notwithstanding the exigencies of war, Spedan Lewis had promised a generous pension scheme for Partners in 1941. With the election of a Labour government to provide a welfare state, the political climate was in keeping with Spedan’s sharing philosophy, as in 1948, he published a 475 page book, Partnership for All, essentially a manifesto, summarized in the final paragraph:

… we should begin now to see how Producer Co-operatives of this general type may be the answer to one of the great problems of our modern civilization, how to make our working lives as fruitful for ourselves and in all other ways as happy as they ought to be and so make ourselves work as well, as for our own sakes we should. (Glancey 2014: 98)

The natural outcome was that in 1950, Spedan signed a Second Trust Settlement, transferring ownership and control to the Partnership. Given that the company is owned by a trust, Partners are unable to sell their shares upon retirement or leaving the Partnership.

Spedan retired in 1955, a difficult transition, after a life’s work with the Partnership. The new Chairman was Bernard Miller, a JLP “lifer,” originally hired in 1927 straight from Oxford, married to a fellow Partner. Miller’s accession coincided with a buoyant economy, enabling him to turn the Partnership into a thriving retail business during his 1955–1972 tenure. Staff bonuses averaged 13.5% during the Miller years topping 18% in 1972. New retail and manufacturing units were added, alongside innovations such as computerized stock control. Miller was concerned to ensure the highest standards in design, business, and staff conditions. Staff retention was very high. Retiring in 1972, Miller left JLP in excellent condition, going on to enjoy a second career as Treasurer and Pro-Chancellor of Southampton University.

The next Chairman, Peter Lewis, was the son of Spedan’s brother Oswald, who had joined the Partnership as a management trainee in 1959, despite having qualified as a lawyer like his father. While the 1970s was a time of unemployment, and strikes, nevertheless the groundwork was still being laid for the emergence of a more affluent and discriminating middle-class, who would be the bedrock of JLP custom. Although Peter had received no special treatment in his rise through the ranks, he showed himself to be highly capable in riding the waves of change in society and consumerism between the 1970, 1980s, and into the early 1990s. Selling space doubled in his two decades at the helm, as Peter undertook ambitious expansionary projects, declaring, “Our calculations are for 25 years, but our hopes are set on a hundered” (Glancey 2014: 158). Technological innovations continued apace, for example, with the pioneering introduction of electronic point of sale (EPOS) systems, as technology experts were recruited accordingly.

Stuart Hampson, a former civil servant who had joined the Partnership in 1982 became Chairman in 1993, following the retirement of Peter Lewis, further expanding the business. Hampson had to endure and counteract a movement among a minority of Partners who believed that every business could be privatized to advantage and embarked on a campaign to float the Partnership on the Stock Exchange. Hampson stood firm, declaring that the company was owned by a Trust set up by Spedan Lewis in such a way to ensure that generations would continue to enjoy the gift of his business. The well-being of a Partnership such as JLP conferred a camaraderie, social life, and economic security in pressured times not present in a private company. Further, Hampson was able to demonstrate the way that JLP had taken calculated risks for the long-term from 1972, by growing thoughtfully and carefully, and was therefore well positioned to a new world of Internet shopping, instant and global electronic communication, and intense competition. In contrast, rivals which had concentrated on short-term vagaries of shareholder demands had not done as well.

When Hampson retired in 2007, he was replaced by Charlie Mayfield, who still serves as Chairman as of 2016. Mayfield joined JLP in 2000 after a distinguished military career, followed by business training and several high-level executive and consulting experiences. In the same year that Mayfield became Chairman, 2007, Andy Street, became Managing Director. Street, an Oxford graduate, had joined JLP straight from University, undertaking a number of senior executive posts, including Supply Chain Director, Director of Personnel and Managing Director of JLP branch stores. In 2014, he was named the “Most Admired Leader” of the year by business magazine, Management Today. In June 2015, he was awarded a CBE for services to the economy, in his roles as managing director of John Lewis and as Chairman of the Greater Birmingham Local Enterprise Partnership. However, in September 2016, Andy Street was unveiled as a Conservative candidate for Mayor of the West Midlands, so he was predicted to step down from his position at JLP.

2 The Business Model

JLP is governed by a Constitution which serves as a framework to define the Partnership’s principles and the way it should operate. The Constitution defines mechanisms to provide for the management of the Partnership, with checks and balances to ensure accountability, transparency, and integrity. Originally written by Spedan Lewis in 1929, the Constitution has been revised on a number of occasions since then, in order to keep it fresh and up to date. In 2009, in the face of the financial crisis, which was publicly perceived as a product of corporate selfishness, JLP unveiled a new Constitution. The Constitution renewed JLP’s vision as a contrast to rampant “corporatism,” basically reiterating the values in which the company was always grounded. These are encapsulated in seven principles:

-

1.

Purpose. The Partnership’s ultimate purpose is the happiness of all its members, through their worthwhile and satisfying employment in a successful business…they share the responsibilities of ownership as well as its rewards—profit, knowledge, and power.

-

2.

Power. Power in the Partnership is shared between three governing authorities, the Partnership Council, the Partnership Board and the Chairman.

-

3.

Profit. The Partnership aims to make sufficient profit from its trading operations to sustain its commercial vitality, to finance its continued development, to distribute a share of those profits each year to its members, and to enable it to undertake other activities consistent with its ultimate purpose.

-

4.

Members. The Partnership aims to employ and retain as its members people of ability and integrity who are committed to working together and to supporting its Principles. Relationships are based on mutual respect and courtesy, with as much equality between its members as differences of responsibility permit. The Partnership aims to recognize individual contributions and reward them fairly.

-

5.

Customers. The Partnership aims to deal honestly with its customers and secure their loyalty and trust by providing outstanding choice, value and service.

-

6.

Business Relationships. The Partnership aims to conduct all its business relationships with integrity and courtesy, and scrupulously to honor every business agreement.

-

7.

The Community. The Partnership aims to obey the spirit as well as the letter of the law and to contribute to the wellbeing of the communities where it operates.

In addition to the Constitution, JLP is also governed by its Articles of Association, the Companies Act, and complies with the Listing Rules and Disclosure and Transparency Rules applicable to a Standard Listed company on the London Stock Exchange (LSE). As JLP has no tradable equity share capital listed on the LSE, it is eligible for exemption from corporate governance disclosure requirements of the UK Corporate Governance Code. Nonetheless, JLP voluntarily applies the UK Code Principles and publishes full disclosure in its Annual Report, so it holds itself publicly accountable. However, as the Partnership’s Constitution and co-ownership model establishes its own unique governance structure, there are certain aspects of the Code with which JLP does not comply. Nonetheless, JLP claims its practices are consistent with each of the Code’s principles, as appropriate, and offer the necessary level of protection to Partners and other stakeholders.

The uniqueness of JLP is its Partnership structure, whereby the Partnership’s shares are held in trust on behalf of its Partners. Given that this structure defines its corporate governance, it follows that it should influence all business activities. The essence of the governance structure and arrangements is to ensure democracy, so that all Partners can have a voice in the running of the company, as per the Constitution which established the representation of the co-owners on the Partnership Board through the election of Partners as Directors (Elected Directors).

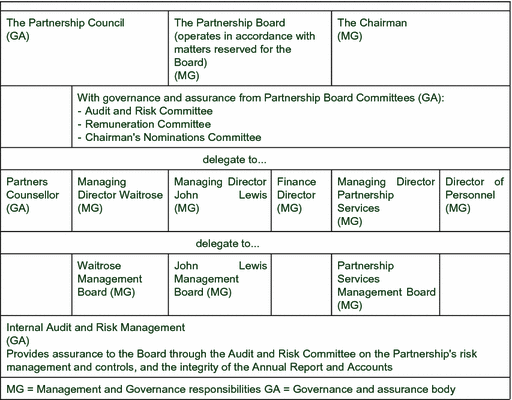

The Partnership has three top governing authorities with overall responsibilities: the Partnership Council, the Partnership Board, and the Chairman:

-

The Partnership Council is deemed the primary democratic medium. It holds the Chairman to account and appoints five directors to the Partnership Board. The Partnership Council is the elected body that represents Partners as a whole and reflects their opinion. It is the voice for ensuring that the business is run for and on behalf of Partners.

-

The Partnership Board is comprised of 5 appointed and 5 democratically elected Partners, 3 independent nonexecutive directors and the Partners’ Counselor. The Chairman appoints five executives to the Board, including the Managing Directors of John Lewis and Waitrose respectively, the Finance Director, and the Director of Personnel. The Partnership Board is responsible for the overall management and performance of the Partnership and operates within a framework of controls, which enable risk to be assessed and managed. It is collectively responsible for the success of the Partnership.

-

The Chairman has personal responsibility for ensuring that the Partnership retains its distinctive character and democratic vitality. The Partnership Board delegates management of the Partnership’s business to the Chairman and he is ultimately responsible for the Partnership’s commercial performance. He is the Chairman of the Partnership Board, by virtue of his appointment as Chairman of the Trust Company. He is also responsible for the leadership of the Partnership Board and ensuring its effectiveness on all aspects of its role.

-

The Partners’ Counselor is automatically a member of the Board. S/he seeks to ensure that the Partnership is true to its principles and compassionate to individual Partners. S/he monitors and upholds the integrity of the business, its values, and ethics as enshrined in its constitution, performing the role of senior independent director in their interaction with Partners as co-owners of the business. The Partners’ Counselor supports the elected directors in their contribution to the Board and thereby helps underpin their independence, convening meetings with the elected directors, without other executive directors being present, as appropriate and at least once each year (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Source www.johnlewispartnership.co.uk, reprinted with permission from John Lewis Partnership

The governing structure of JLP.

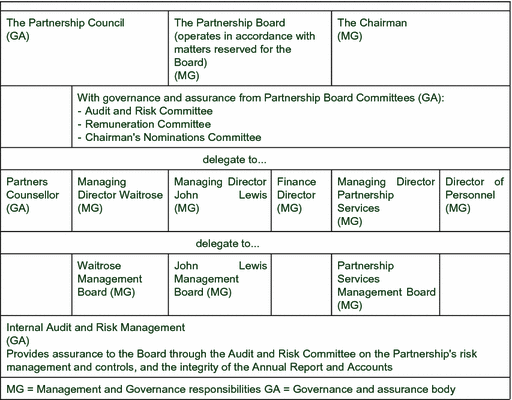

Figure 2 portrays how the governance arrangements translate into the implementation of policy and strategy in the company, emphasizing that it is not meant to be the traditional top-down hierarchical organization, but one where everyone is equal.

Source www.johnlewispartnership.co.uk, reprinted with permission from John Lewis Partnership

JLP democracy in action.

JLP applies the same value chain procedures in all of its divisions. It is comprised of four components, which JLP states to be unique among its peers as follows:

-

“Careful sourcing”—JLP claims it develops and selects third-party branded quality products to meet customer needs, and develops high quality, innovative own-label ranges. It asserts that it has many exclusive and often long-standing sourcing Partnerships with suppliers for key products, thus giving greater influence over quality and provenance. In 2016 in response to the UK Grocery Code Adjudicator, Waitrose was one of 10 supermarkets to improve its payment terms to suppliers by pledging to pay its small food suppliers within 7 days of delivery, better than other grocers like Tesco with a 14 day limit.

-

“Efficient distribution”—JLP claims it moves its carefully sourced products cost-effectively to shops and customers, having invested significantly in distribution and logistics infrastructure over the past few years.

-

“Convenient, excellent shopping experience”—JLP claims it serves its customers by providing a superior end-to-end shopping experience, through a market leading omnichannel service, offering customers unrivaled choice, experience, and convenience.

-

“Developing enduring customer relationships”—JLP claims to provide value for money and outstanding customer service before, during and after purchase, wherever and however they shop. This is achieved through award-winning customer service and after-sale support, which leads to enduring customer relationships.

Thus, JLP maintains that its value proposition ultimately creates value with respect to financial performance, and contributes to the welfare of its Partners, suppliers, customers, communities, and the environment.

JLP’s strategy aims to enable Partners successfully to add more value to the business than employees do for its competitors, and therefore earn more as a result. This will be achieved by targeting the most valuable customers who shop across its brands, thereby gaining the Company a greater share of their spend. Parsimonious about advertising in the tradition of John Lewis himself, JLP accumulated a reputation at the point of sale with the customer, deemed, “the moment of truth.” There was an emphasis on superior design in all aspects of the value chain—goods, packaging and corporate color schemes—as the hallmark of JLP, with a model of clean lines, modesty, and good taste.

Knowledge sharing is facilitated through representative bodies. Through improved processes and clearer responsibilities, growth should be funded through better efficiency and operating margins. The JLP strategic approach is based on “logical incrementalism,” whereby change is implemented in small steps, with lessons from each phase informing the next (Ghobadian 2013). It has applied this approach in its product offerings, store formats, online technology, and international expansion to South Korea and Dubai.

The company has been considering what it might do in the future, with a group set up to look at what the world might be like in 2028. “The reason we chose that date was it’s 100 years after Spedan Lewis inherited the business from his father,” Mayfield says. So what markets could John Lewis go into? “I don’t look at just what markets we can see today, like holidays or hotels or restaurants,” he says. “Instead what’s more interesting is to think about what markets might grow from almost tiny beginnings - maybe they’re not even present today—but in 20 years’ time could be really significant. In which of those markets would our competitive advantage count for most?”—including further international expansion. JLP invests some resources through its JLAB unit in accelerators or incubators, i.e., start-up companies that could be the source of technological breakthroughs, also offering training and mentorship to these fledglings.

The company aims to satisfy certain ambitions through its strategy. These are to increase the advantage of its Partners through job satisfaction, gross sales and profit per average full-time employee (FTE), low staff turnover, and increased number of Partners. In the John Lewis division, the strategic priority for Partner advantage is Partners taking ownership of their success, while in Waitrose, priorities are an investment in Partner development and progression and supporting productivity.

An allied aim is to enhance market potential through increasing the number of shops, selling space, gross sales, gross sales per selling square foot, and percent of customers shopping in both the John Lewis and Waitrose brands. John Lewis prioritizes outperformance in its current markets and growing its online business, nevertheless growing its physical space. In fact, the company has discovered synergy between physical and online presence, as the presence of a department store can boost online business. About one-third of John Lewis department stores sales are online and growing in 2016, with increasing customer preference for picking up goods ordered online in the store. John Lewis became the first store to charge for “click-and-collect” for orders under £30, as a free service was deemed “a bonkers business model” by Managing Director, Andy Street (Skapinker and Felsted 2015). This is due to the fact that every item sold online carries a cost of picking, purchasing, and delivery. Likewise, Waitrose is not only building its online presence, but also intends to develop compelling reasons to visit its shops. Waitrose highlights investment in product innovation and value and deepening customer relationships through its loyalty scheme, “myWaitrose.”

The third aim is to grow efficiently by generating sustainable returns via increased Partnership profit margins, cash flow, and return on invested capital. In John Lewis, this will be achieved by driving efficiency to exploit scale and diversifying into new products and services. In Waitrose, this means opening new retail space and investing in IT and distribution.

An important part of JLP’s strategy is risk management. As can be seen from Fig. 1, the Audit and Risk Committee which reviews the effectiveness of the risk management process is one of the main governance bodies. Each Division is responsible for identifying, evaluating, managing, measuring, and monitoring the risks in their respective area. Divisional Risk Committees oversee the effective use of the risk assessment process, with assistance from the Group Head of Risk and Divisional Risk Managers. Internal Audit reviews internal controls using a risk-based audit plan.

The following is a summary of 2015 financial performance compared with 2014.

-

JLP—Gross sales, a measure of sustainability and performance against the overall market was £10.9 billion, up 5.7%. Both Waitrose and John Lewis grew sales well ahead of their respective markets, increasing their market share. Waitrose outperformed the Kantar Grocery Market by 4.8% and John Lewis outperformed the BRC Retail Index by 4.9%. Operating profit before exceptional items was £442.3 million, down 7.5%; Operating profit after exceptional items was £450.2 million, up 4.7%. Gross sales per FTE (full-time employee), a productivity measure, decreased from £182,000 to 181,600, reflecting a decline in gross sales per FTE in Waitrose, where FTEs grew at a faster rate than the sales growth. This was offset to some extent, by an increase in gross sales per FTE in John Lewis. Partnership profit per FTE, an efficiency measure, decreased to £5700 from £6700, principally due to the decline in operating profit and the increase in average FTEs. Return on invested capital, a measure of long-term value creation has decreased from 8.3 to 7.6%, principally due to the decline in operating profit in Waitrose.

-

John Lewis—Gross sales £4.4 billion, up 7.5%; operating profit margin £250.5 million, up 10.4%; operating profit margin 7.1%, up from 6.9%; like-for-like sales growth 6.5% up from 6.4% the previous year.

-

Waitrose—Gross sales £6.5 billion, up 4.6%; operating profit £237.4 million, down 24.4%; operating profit margin 3.9%, down from 5.4%; Like-for-like sales growth 1.4%, down from 5.1%.

Thus, we see that Waitrose is under pressure, compared to John Lewis which appears to be thriving. Further evidence is seen in an increase in gross sales per average FTE from £175,000 to £186,000, and gross sales per square foot up from £902 to £947 for John Lewis. In contrast, Waitrose suffered a drop in gross sales per average FTE from £197,200 to £188,500 and in gross sales per square foot from £1126 to £1124.

Acknowledged global and retail trend challenges require appropriate responses by JLP. Global challenges are globalization of supply chains, volatility in commodity prices, concerns about the physical environment and about health, inequality, and diversity. Retail trends are food price deflation at the highest level since the 1970s, intensifying competition, the rise of convenience shopping and technology demanding flexibility and convenience for customers. Transparency about corporate conduct and where and how products are sourced and made is a key for customer trust. An additional issue was the decision by referendum for the UK to leave the European Union, and how this might impact JLP’s costs, revenues, and profits.

JLP has responded by investing in refurbishing and upgrading existing shops, installing new systems and distribution capabilities, adopting new technology, and reshaping operations to serve new customer needs. With market pressures, JLP is placing more emphasis on efficiency and less on growth to achieve profit. Above all, JLP wants to underline that Partners play a vital role in growing profitability through personal contributions as co-owners to become more productive. In some cases, this will mean role changes, with some lost and others created. It also means a greater contribution from Partners through personal development, job design and technology. “This is not about ‘working harder’. It is about our ability to offer worthwhile and satisfying jobs. It is the sustainable way to enable growth in Partners’ pay and bonus levels” (Annual Report 2015).

In the past decade or so Waitrose has doubled in turnover and trebled its profits, while JLP has both built and grown a successful online business faster than many competitors. However, profit metrics compare unfavorably to competitors. For instance, its profit margin before tax and a payout to Partners of 3.2 or 3.8% if a £60 million charge for pension costs is added back, is less than the 20% margins achieved by Next and 6.5% by M&S. Each staff member generates profits of £4000, compared to £16,000 at Next and £8000 at M&S (Guthrie 2016).

Although it is private, the John Lewis Partnership has been prepared to tap capital markets, issuing a £275 million bond in March 2014, to fund John Lewis and Waitrose.

The pressures acknowledged by JLP continued into 2016, as half yearly pre-tax profits slumped by 14.7% to £81.9 million, excluding exceptional property items. Sales rose 3.1% but profit was held back by price competition, pay increases, IT costs, and a new distribution network including a £150 million depot extension. The results came with a warning that fewer staff might be employed over time in order to tackle a soaring wage bill after it raised salaries across the company to ensure that all Partners are paid at competitive rates, entailing a £33 million jump in staff costs. The Partnership proclaimed that the higher pay depends on better productivity and greater contribution, so it anticipated fewer Partners over time.

The group wrote down £25 m relating to the value of property acquired to develop seven Waitrose supermarkets that it no longer planned to open. Chairman Sir Charlie Mayfield declared that while there had been little effect from the UK vote to leave the EU, uncertainty created by the referendum result would linger. One immediate impact of the Brexit vote was that the group’s pension deficit soared by £512 million to £1.44 billion because of falling yields on bonds used to fund the scheme.

In 2015, the Partnership bonus was 11% of pay, a drop from 15% in 2014. Of course, bonus is calculated as a percentage of salary, so higher paid workers receive significantly more than shop-floor workers. In contemporary challenging trading conditions, the Partnership must be agile and responsive in today’s market place, while remaining true to its longer term Constitutional purpose and principles, and JLP has taken various measures in this regard.

First, to foster a culture of inclusivity, involvement, and contribution across the Partnership, JLP launched the “It’s Your Business” movement to engage Partners in ownership, including a Partnership Day, while also establishing Pay for Performance as part of the Partner Plan to ensure a fair approach to pay awards. The Gazette was relaunched to strengthen independent journalism and new functionality was added to internal digital communications. A Pension Benefit Review was concluded with the unanimous support of Partnership Council and a £300 m, 20-year bond was raised to prepay previously agreed deficit reduction contributions to the pension fund. While the original Constitutions stated no one in the Partnership should be paid more than 25 times the pay of a full-time London-based Partner, in 2012, a revised Constitution increased the ratio threshold to 75 times.

The Partner pulse score, where Partners are asked if their division is a great place to work, went from 51 to 59%. However, overall Partner satisfaction went down by 2 to 72%. Cathcart (2013) has unearthed tensions in the Partnership, which has been accused by some observers of operating a pseudo-democracy which does little to address inequalities of power in what is a hierarchical management organization. Strain results from fluctuating visions of managers and workers for the Partnership and how to achieve those visions. While managers welcome frank exchanges of views, they also demand loyalty and support for their decisions. Meanwhile, the non-management staff wants meaningful input into key operational rather than strategic decisions, but indicate faith in their management. Partners appreciate their right to be critical on an anonymous basis in the letters in the staff magazine.

Alongside the better cost-cutting strategies of rivals such as M&S, Partner productivity is a concern as JLP approaches its improvement in a number of ways—“inspire” Partners to get involved in continuous improvement (CI) initiatives for productivity; “embrace” technology that enhances productivity; encourage flexibility; review sick absence arrangements, and working patterns and mix of part-time and full-time Partners

3 Problems and Challenges

Given the glowing public view of JLP, are there any challenging issues on the horizon? Chairman Charlie Mayfield explained, “I think people sometimes view the Partnership as some land of milk and honey where nothing bad ever happens,” he says of staff complaints. “And it always makes me smile in a wry way because it really, really does a disservice to the vigorous and constant debate that goes on within the Partnership about how we’re performing and where we need to do better. This is a very self-critical organization and that’s actually an enormous strenght” (Skapinker and Felsted 2015).

Nearly one-third of Partners are not satisfied and almost half don’t think it’s a great place to work, so the happiness of all the Partners envisaged by Spedan Lewis is not satisfied. The new “It’s Your Business” drive reflects that Partners have not taken on the responsibilities of ownership to the extent required by the business imperatives facing the company. For example, new formats, such as the Waitrose store in Salisbury will require more Partner input and skills. The idea that Partners own the business, so they are all concerned and motivated to outperform needs to be embraced more than it appears to be at present. A vicious cycle is created when profits decline, entailing a cut in bonuses, which may itself be demotivating.

Notwithstanding its egalitarian aspirations, the company is essentially run via a hierarchy, and pay differential tolerances have recently increased. In the Gazette, one Partner wrote that “there were too many people in charge—assistant section managers, department managers and store managers. One can almost hear Partners singing the song, ‘You don’t know what you’re doing.’” Concerns about the nature of the Partnership in relation to JLP’s productivity and cost base are expressed, partly the trade-off between investing in staff and good service and partly, inevitably, JLP’s longer term focus (Skapinker and Felsted 2015). Its unfavorable profit margin and productivity metrics compared to rivals are evidence of a trade-off rather than synergy between Partnership and profit. An allied possible problem is continued replenishment of talent at the top, given the imminent departure of the Managing Director of JLP, not long after the departure of Mark Price, former head of Waitrose.

How is claimed value creation different to any other well run business? Competition in retailing is intense. The way people throughout the wealthy world shop has changed. Customers are no longer loyal to one company, however, admired it is. They are well-informed about what things cost and they expect goods to be brought to them with speed and accuracy.

Some of the problems and challenges facing JLP can be seen in its self-identified risks in its risk management operations. Risks are assessed by Divisions and Directorates half-yearly, considering the potential impact of the risk and the likelihood of its occurrence. Evaluation of impact and likelihood is made after consideration of the effectiveness of current mitigating controls in place. “Red zone” risks are considered too risky for the return and against acceptable risk tolerance, so an urgent response is required to bring the risk back to an acceptable level. In 2015, JLP identified 23 principal risks, of which 10 were “red” and 13 were “amber”, i.e., considered as being managed satisfactorily, so no additional actions other than regular monitoring are required.

The ten red zone risks would be applicable in any business operating in a competitive landscape, and they fall under four headings: strategic, operational, financial, and compliance.

Competition—Aggressive price competition puts pressure on margins and profitability, especially in the current environment in the retail grocery sector. The price war in the UK was occurring in all parts of the market, of which high-end Waitrose had a share of 5.2% in 2016, compared with Tesco at the highest share of 28.2%. German grocery discounters, Aldi and Lidl are increasingly invading Waitrose territory, going upmarket, e.g., offering lobster and champagne.

Waitrose had been overtaken by German discounter Aldi which stood at 6.1% share. Amazon is expanding its offerings with own-label merchandise and groceries, as well as online grocery deliveries, in pursuit of market share, especially from affluent customers. Given its economies of scale, Amazon is a formidable rival.

Actions—Competition means that Waitrose customers focus more on value for money and less on loyalty. Therefore Waitrose responses entail: Tracking competitor impact and customer perceptions; focusing on the customer experience as a point of differentiation, including “myWaitrose” benefits to offer additional value to customers; implementing efficiency projects to protect margins. An example is a new Waitrose format store in Salisbury which creates the supermarket as a day out, with a restaurant, cafe and wine bar, and a centerpiece cookery school for adults and even children’s parties. Waitrose has set up a loyalty scheme, “Pick your own offers,” enabling customers to choose 10 products on which to receive 20% savings every three months. However, the scheme could cost Waitrose £5 million weekly.

Economic environment—A worsening external economic environment, a static economy and lack of pay increases, reduces customers’ spending power and harms suppliers’ financial resilience. In this respect, the UK referendum result in June 2016, to withdraw from the EU was seen as posing a real threat to the economy, from a loss of consumer confidence and more costly overseas sourcing from a weakened sterling currency. However, this would affect the likes of Aldi and Lidl, which sourced their products from outside the UK, more than JLP. Also, given its non-Limited Public Company (PLC) structure, JLP would not have been affected by the 11% drop in share values suffered by London listed retailers after the referendum.

Actions—Try to deliver the highest levels of customer service, product quality, and product innovation; securing value for customers through range selection and price matching commitments, while continually introducing new products and services to anticipate changing customer requirements; developing long-term relationships with suppliers.

Operating model strain—Changing customer requirements, a shift to online and the need to increase investment in supply chain and IT put a strain on the operating model, threatening ability to meet customer needs and grow profitably.

Actions—Significant investment in IT infrastructure and supply chain to support efficiency and continue development of an omnichannel proposition; implementing sales initiatives and continually introducing new products and services to meet changing customer requirements; all change initiatives must consider Partner impact.

IT infrastructure capability—With growth and change in customer needs change, so existing IT infrastructure becomes less “fit for purpose.”

Actions—Aligning IT strategy with business strategy to enable the sustainable change required; IT restructure programs are in progress to provide resilience and protect the Partnership; system backups are in place to provide business continuity, and service level agreements are in place with IT third parties.

Change delivery—Due to the size, nature, and complexity of the change agenda, there may be issues with planning and governance, resourcing and investment, and engaging Partners.

Actions—Heads of Portfolio Management develop and manage change capability; significant investment has been made in specialist project management support through working groups, steering groups, group and divisional change boards to provide pan-Partnership program governance.

Efficiency—There is a risk that programs to optimize efficiency and productivity fail and, therefore, the required savings are not delivered to respond to a changing environment and pressures on the operating model.

Actions—Specific projects and programs, to focus on current and future efficiency and productivity; project management capability assigned to all major projects, and external specialists used when required; change Boards in place to monitor current efficiency programs and enable early identification of any issues.

Talent—In a changing and competitive market and in consideration of the Partnership model, constant assessment of talent needs to deliver business goals and how to can attract, develop, and retain talent are required.

Actions—Annual talent reviews ensure that top talent is identified, developed and succession plans exist for key roles; Leadership Development Programs in place to support succession and capability needs of the Partnership; Benchmarked benefits and remuneration to support competitive reward.

Pension obligations—The open nature of the Partnership’s defined benefit scheme could lead to a future increase in pension liabilities, with the risk of a significant pension deficit.

Actions—A Pensions Benefit Review approved by the Partnership Council and the Partnership Board and implementation of the new arrangements initiated; valuation assumptions and pension funding strategy have regular external and internal monitoring and review; a project to investigate means to further de-risk the pension fund investment portfolio initiated.

Property valuation—Continuing market shifts in the retail grocery sector, from the current channel format toward online and convenience stores, could cause a fall in freehold estate valuation for Waitrose’s freehold properties.

Actions—All property acquisitions are reviewed by the appropriate Management Boards and annual post investment reviews are performed on new acquisitions for their first three years. Annual impairment reviews are performed. A review is in progress to assess the appropriateness of the property portfolio and mix between freehold and leasehold.

Data protection breach—Increasing external attempts to cause disruption or access sensitive data and the pace of technological development may cause vulnerability to a breach of Partner or customer data.

Actions—Policies and procedures to protect our Partner, customer and operational data; IT security controls in place, including network security and regular penetration testing, provide early identification of network or system vulnerabilities and weaknesses; Data and IT Security Improvement Programs are being implemented across the Partnership.

4 Conclusions

JLP’s 150th birthday celebration, and the last century of it as a workers’ cooperative is a testimony to its sustainability. It enjoys a singularly positive reputation among retailers in the UK as an ecologically sustainable, future respecting and pro-social enterprise, and has been in profit all of its existence. The idea is that ownership confers psychic and material benefits to workers, while also demanding responsibility and accountability to fellow Partners. Even as workers’ cooperatives go, JLP is unique, as it was not formed by a group of workers, but by a capitalist owner who chose to give it away to the workers. Thus, it is grounded in its distinctive history as embodied in Spedan Lewis’ strong views and radical vision. The company is very conscious of its history and its roots, as can be seen in its proud in-store exhibition and the publication of a volume to celebrate its 150th birthday in 2014. The “happiness of Partners” as enunciated by Spedan Lewis, remains its primary aim.

JLP appears to meet all four criteria of good governance in cooperatives—member voice, representation, expertise, and management (Birchall 2014; O’Higgins 2015):

Member voice—In JLP, a strong sense of identity of its members/Partners is based on its shared core purpose “the happiness of its members” as enshrined in the Constitution written by Spedan Lewis. The Partners recognize very strongly the link between job satisfaction, based on superior work performance and a successful business that results in fulfillment of the common purpose of happiness. Partners do not have the option to sell their shares and a large proportion of JLP Partners are “lifers.” Thus, the employees are committed and express their voice through their everyday work, thereby building the business over the long-term. The structure of JLP shows that Partners have direct access to the highest echelons while they usually participate in committees to express themselves. If necessary, they can also air any concerns anonymously through the weekly Gazette.

Representation—In JLP, there is an effective formal representation system, whereby the Partnership Council (directly elected to represent the Partners) influences the policy set by the Partnership Board. This board functions as a board of directors, akin to any listed company. But it also represents, by its composition, the Partnership nature of the business with five directors appointed by the Partnership Council. Moreover, a Partners’ Counselor is a member of the Board, specifically to look after the interests of the Partners.

Expertise—The necessary expertise to run the business successfully starts with the top board composed of five executive directors who understand the various facets of the business and three external independent nonexecutive directors. This level of expertise at the board increases the likelihood that the business will work effectively on behalf of its members, while the strong input from Partners who know and understand the business insures capability at all levels of running the enterprise.

Management—The senior management team is comprised of professional managers with experience in running a business, especially in a customer focused retail enterprises. This professionalism is applied to enacting the principles on which the success of the business is based: “value, assortment, service, and honesty” and “never knowingly undersold.”

The management of the business appears to be able to achieve a delicate balancing act between business decisions and cooperative principles. For example, 90% of employees affected by job cuts are redeployed. A strength of the cooperative model is its long-term sustainability orientation, as opposed to concentration on short-term results to please capital markets. To that end, JLP adopts an incremental adaptive, but future oriented approach to strategy. This is seen in its many initiatives in change management at all levels of the organization and its establishment of JLABS investments in accelerators and incubators. Its recognition of and addressing of risks on the horizon demonstrates its long-term orientation. Also, JLP was an early adopter of digital media in all aspects of its value chain and the company is ahead of its rivals in fair treatment of suppliers. Another example is issuing bonds for investment and business development purposes, belying the critics of employee owned cooperatives about under-utilization of external debt despite a strong collateral position, thereby curtailing growth (Estrin and Jones 1992).

However, as of 2016, JLP is faced with challenges which may threaten its very model. Its primary aim of Partner happiness is not being entirely met, according to surveys. Many economists such as Williamson (1985) regard cooperatives as long-term inefficient because of lack of hierarchy and performance monitoring problems. JLP does, in fact, have a hierarchical management system, but there are signs of dissatisfaction with it, much as one might find griping with the hierarchy in any company. It remains to be seen how its individual “pay-for-performance” introduction will work in a context where intrinsic motivation and self-management and self-monitoring have been guiding principles. Initiatives to encourage all Partners to take on responsibilities to meet the contemporary challenges facing the company suggest that there is insufficient collective buy-in and effort, an expected mainstay of cooperation. Thus, we see cracks appearing in the Partnership Foundation. Moreover, these are appearing in an environment of severe competitive pressures, where higher productivity is needed. The threat of fewer Partners could have a demoralizing effect, especially when growth is being curtailed. Procrastination by Partners in assuming responsibility for change and carry out proposed actions could be the undoing of JLP.

We might ask whether a rise in dissatisfaction by Partners is a sign of healthy self-criticism. Are Partners unrealistic in expecting too much in the way of “happiness?” The situation also has to be seen in context, as the Partnership survived a rebellion in the past when a number of Partners tried to convert it into a public limited company.

Is a “John Lewis model” transferrable? Mark Price, former JLP deputy chairman and head of Waitrose, observed that the philosophy that underlines the Partnership could be replicable, but the specifics of how the Partnership works are probably not. Possibly companies with a more traditional structure could try to adopt some of John Lewis’s three vital features: rewarding people and acknowledging that they have a life outside work, telling them what is going on, and involving them in decision-making (Skapinker and Felsted 2015). Indeed, JLP’s advantages rely on its unique history which dictates inherent and often tacit attitudes, routines, and emotional and moral commitments developed over many decades. Such a context provides comparative advantage to JLP, a criterion of which is inimitability, alongside its value and scarcity or matchlessness.

However, does JLP’s very uniqueness in structure, history, and culture have within it the seeds of its own destruction? The Company’s awareness of the balancing act it must continue to perform is clearly enunciated in its current Annual Report exhortation/maxim, “It’s Your Business” to take personal responsibility. This is juxtaposed with JLP’s Constitution which proclaims: “a better form of business, and the challenge for Partners of today is to prove that a business which is not driven by the demands of outside shareholders and which sets high standards of behavior can flourish in contemporary competitive conditions and, indeed, to demonstrate that adhering to these principles and rules even enables long term outperformance over companies with conventional ownership structures.”

5 Questions to Address

-

Why has JLP been successful thus far? Does JLP’s unique business model and governance structure offer better sustainability than the typical retailer company structure?

-

Has JLP escaped potential disadvantages of employee owned cooperatives in general, such as limitations to growth?

-

Are JLP’s structure and arrangements transferrable to other retailers and companies in other industries? Or, are these a once-off because of JLP’s unique history?

-

What are the strengths and weaknesses in JLP’s business model in dealing with contemporary competitive pressures in retailing in its markets? In relation to the challenges facing JLP in 2016, and in the international context, are its responses sustainable? Can additional or alternative responses or approaches be recommended?

-

Do the challenges confronting JLP constitute a threat to its very Partnership structure? Is the Partnership model fit for purpose at all in the environment of the early twenty-first century? Should JLP become a public listed company or assume some other form?

References

Birchall, J. (2014). The governance of large co-operative businesses. Manchester: Co-operatives.

Cathcart, A. (2013). Directing democracy: Competing interests and contested terrain in the John Lewis Partnership. Journal of Industrial Relations, 55(4), 601–620.

Estrin, S., & Jones, D. C. (1992). The viability of employee- owned firms: Evidence from France. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 45(2), 323–338.

Ghobadian, A. (2013, July 23). Growth by small-change innovation: John Lewis’s ‘logical incremental’ style’. Financial Times, p. 12.

Glancey, J. (2014). A very British revolution: 150 years of John Lewis. London: Laurence King Publishing.

Guthrie, J. (2016, January 25). Mayfieldmania does make John Lewis a model for quoted companies. Financial Times, p. 20.

JLP (2015). John Lewis Partnership Annual Report and Accounts 2015. https://www.johnlewispartnership.co.uk/content/dam/cws/pdfs/financials/annual-reports/john-lewis-partnership-plc-annual-report-2015.pdf

O’Higgins, E. (2015). Is the co-operative model a realistic alternative to traditional joint-stock companies? In G. Enderle & P. E. Murphy (Eds.), Ethical innovation in business and the economy. Northampton MA: Edward Elgar.

Skapinker, M., & Felsted, A. (2015, October 17/18). Trouble in store. Financial Times Magazine, pp. 11–18.

Williamson, O.E. (1985). The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. New York: Free Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

O’Higgins, E. (2018). The Ethos of Partnership: The John Lewis Partnership. In: O'Higgins, E., Zsolnai, L. (eds) Progressive Business Models. Palgrave Studies in Sustainable Business In Association with Future Earth. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58804-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58804-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58803-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58804-9

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)