Abstract

Corporate culture is a relatively new matter of interest for financial institutions . However, it deserves increasing attention within the more advanced academic debate, as well as among experts, professionals, and policy makers.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Corporate culture is a relatively new matter of interest for financial institutions . However, it deserves increasing attention within the more advanced academic debate, as well as among experts, professionals, and policy makers.

Banks are realizing that culture is a sort of “missing link” in the understanding and governance of individual and social behaviors within corporate organizations, and that it has been long overlooked or taken for granted. At the same time, regulators, and supervisors are convincing themselves that sounder banking culture and conduct represent important value drivers also for other relevant stakeholders. In fact, the financial crisis was seriously exacerbated by an inadequate risk culture in the financial sector. In other words, there was a deep cultural problem under the decisions and behaviors that brought to the crisis. And several cases of misconduct and scandals can be fully explained only in light of the same cultural weaknesses in banks and other financial companies.

We believe that the academic literature addressed with delay (with few exceptions) the topic of corporate and risk culture in financial institutions . This delay is due to perhaps the fact that this research field requires a multidisciplinary approach. Studies on risk and on risk culture followed for a long time two highly different paths, with few interconnections, because of the high level of specialization, which increasingly characterizes scientific knowledge .

This explains why many authors did not approach the subject at all or, when they did, started every time from scratch and referred only to their individual wealth of knowledge. We believe that an interdisciplinary approach adds value to the investigation of risk culture in banks. In the present economic and financial context, no regulator, no professional family, no discipline alone is able to assess beforehand and react to risks, as well as to social and individual misbehaviors, because these overcome the traditional boundaries of knowledge , best practices, and controls.

Our book deals with risk culture in the banking sector. We adopted a broad and thorough perspective, based on the academic research and field experience carried out by a large group of authors. All of them were involved for a long time in exploring the topics examined in this volume, which were also discussed at international level in academic and professional conferences and seminars.

The book is divided into two parts. Part I, “General view: theory and tools”, is dedicated to the theoretical grounds of risk culture and the tools aimed at assessing and measuring it. This part is composed of eight chapters.

In Chap. 2 “Risk culture”, Alessandro Carretta and Paola Schwizer explain why corporate culture matters. A suitable culture implies that people “make use” of the same assumptions and adopt behaviors inspired by the company’s values; this enhances the market value of the company identity . The authors define risk culture, its scope, drivers, and effects. Risk culture is central to banks as it influences their risk-taking policies, and behaviors are a direct expression of it. But how can a really “new” culture be developed and spread in a bank today? Such an overreaching process of cultural change involves several actors: bank shareholders, management, bank staff, parliament, the government, the legal system, supervision authorities, the media, the education system, and customers. They all have in some way contributed to the present unsatisfactory situation with small or large measures of responsibility or negligence. What is important today is that all these forces are involved in a joint effort to bring in a new banking culture, acceptable to banking authorities on the one hand, and to clientele on the other. And importantly, banks themselves need to take an active role in this new cultural change centered on them.

Marco Di Antonio, in Chap. 3 “Risk culture in different bank businesses”, highlights that the nature of the business is one of the determinants of risk culture and can lead to subcultures in large diversified financial institutions . Key factors in explaining business-driven risk culture are the two following: Structural factors, i.e., activities performed and their embedded risks, nature, and role of customers, the economics of business; and contingent factors, such as competition, regulation, strategic orientation , etc. The former are intrinsic and quite stable characteristics of the business. The latter instead can change over time, but indirectly affect risk culture and its evolution.

Alessandro Carretta and Paola Schwizer, in Chap. 4 “Risk culture in the regulation & supervision framework”, support and discuss the regulatory approach to risk culture. The increasing attention to risk-taking and effective risk management requires a regulatory intervention in order to promote the inclusion of strategic choices regarding risk appetite and risk tolerance , as well as risk culture among the elements being assessed by supervisors. The challenge for supervisors is to strike the right balance between carrying out a more intensive and proactive approach, while not unduly influencing strategic decisions made by the institution’s management. On the other hand, rules alone cannot determine a final change in corporate culture . Therefore, it is essential that authorities maintain a certain distance to banks’ strategic and policy choices in order to support the growth and consolidation of an appropriate risk culture, tailored to individual business models and corporate characteristics.

Risk culture is a fundamental element of internal governance . Doriana Cucinelli, in Chap. 5 “Internal controls and risk culture in banks”, outlines that corporate culture was at the heart of regulation on the internal control system since the very beginning. Regulators moved from the concept of “control culture”, stated by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in 1998, to “compliance culture” (affirmed in the provisions issued in mid-2000) and recently, in the wake of the crisis, to “risk culture”. Only where a bank can define and disseminate values of integrity, honesty, and attention to the risks among all levels of the organization, can the internal control system effectively achieve its objectives.

Daniele Previati, in Chap. 6 “Soft tools: HR management , leadership , diversity”, discusses the main theoretical and empirical findings of different streams of knowledge that are directly or indirectly linked to the role of people in establishing and changing risk culture in financial institutions . He goes back to basics and identifies (both theoretically and practically) some key issues and research paths integrating risk culture, people, and organization design in the financial services industry. He finally draws a research agenda for the future, stating the need for a renewal of organizational and behavioral analysis about RC.

Nicola Bianchi and Franco Fiordelisi, in Chap. 7 “Measuring and assessing risk culture” develop a new approach to measure risk culture at the bank level and empirically analyze the link between their risk culture measure and bank stability. Although a weak risk culture was one of the drivers of the banking crisis, there is no empirical evidence about the relationship between bank risk culture and stability. Bianchi and Fiordelisi fill this gap: focusing on the FSB framework, they provide evidence that the Tone-From-The-Top feature is the most significant component of the risk culture and this is associated to a greater banks’ stability.

Chapter 8 “Impact on bank reputation”, by Giampaolo Gabbi, Mattia Pianorsi, and Maria Gaia Soana, presents an empirical analysis of the impact of risk culture on financial institutions ’ reputation. The authors investigate how sanctions imposed by supervisors for risky behaviors (considered as a proxy of poor risk culture) determined abnormal returns of two Italian banks sanctioned for misbehavior. The results show that the net impact on capitalization of the banks was larger than the impact of the sole operational losses , thus detecting a reputational effect.

Vincenzo Farina, Lucrezia Fattobene and Elvira Anna Graziano, in Chap. 9 “The watchdog role of the press and the risk culture in the European banking system”,show the role played by mass media in controlling banks’ risk-taking behaviors and in shaping their risk culture. They construct a media attention index based on the news coverage about banking risk issues, processed through the text-analysis technique. They relate this index to the asset quality of European banks, finding a positive although weak correlation with NPLs , which could, however, be only a reflex of some specific bank episodes in various countries.

The second part of the book, “Good practices, experiences, field & empirical studies”, includes a set of relevant contributions on risk culture focused on the individual business areas, measurement techniques, and categories of risk. The second part of the book is composed of nine chapters.

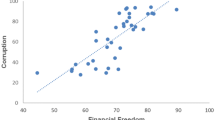

In Chap. 10, “Influence of National Culture on Bank Risk-Taking in the European System”, Candida Bussoli focuses on how different cultural values across the 28 EU countries affect bank risk policies and behaviors. She finds a weaker association between culture and risk-taking in large banks than in smaller ones. The study reiterates that culture may interact with the social, economic, and political forces to produce results and outcomes. Even in globalized financial systems, the formal observance of common rules is not sufficient to ensure a proper risk management ; it is necessary to consider the relief of informal institutions, such as culture, to improve financial decisions.

Discussing a similar topic, Federica Sist and Panu Kalmi, in Chap. 11 “Risk-taking of European banks in CEECs: the role of national culture and stake vs shareholder view”, include an ownership effect ( shareholders vs stakeholders). From the point of view of branches and subsidiaries, they find lower risk-taking if the power distance dimension is low. When the autonomy of subsidiary is lesser, as, in the case of higher level power distance, the procedures for risk assessment are less flexible. The results suggest that banks with cooperative BHCs in CEECs behave in the same way as commercial banks in facing cultural characteristics of a host country, which can likely be caused by the homogenous instability of CEECs submitted to constant reforms.

A specific case study on cultural differences among bank business models is provided by Umberto Filotto, Claudio Giannotti, Gianluca Mattarocci, and Xenia Scimone in Chap. 12 “Risk culture in different bank business models: the case of real estate financing”. The research focuses on the relevance of cross selling to lenders exposed to the residential mortgage market. The analysis of the lending industry during the financial crisis scenario is a useful stress test for evaluating the business model reaction driven by corporate culture . The authors compare trends in cross selling and real estate loans for a representative set of European banks and show that some banking features, including size and real estate loan specialization, may affect the link between residential real estate loans and cross selling.

A further insight into business-driven subcultures is provided by Paola Musile Tanzi in Chap. 13 “Supporting an effective risk culture in private banking & wealth management ”. One of the biggest challenges in this area is how to comply with the rapidly evolving regulatory environment, which implies being able to invest in terms of risk culture, risk management , and risk control , while maintaining an appropriate cost-income ratio. In her view, the choice of the proper business model is the strategic starting point. It is therefore important that risk culture becomes substantial, effective and able to push all the organization to become more risk aware, without losing entrepreneurial spirit .

Gianni Nicolini, Tommy Gärling, Anders Carlander and Jeanette Hauff, in Chap. 14 “Appetite for Risk and Financial Literacy in Investment Planning” empirically investigate whether and how a low financial literacy influences investment decisions. A lack of understanding of financial risk might cause a negative risk attitude with the consequence for optimal investment behavior that the positive relation between risk and return is not properly taken into account. Their results confirm that a lack of financial knowledge negatively affects individual risk attitude, and may seriously bias personal investments.

Turning back to credit risk, Doriana Cucinelli and Arturo Patarnello, in Chap. 15 “Bank credit risk management and risk culture”, present a survey on the structure and organization of credit risk management and on the changing role of the credit risk officer in a sample of Italian banks. Effective risk management systems represent a prerequisite for promoting risk culture in banks and spreading its principles throughout the various levels of the organization. The results demonstrate that banks have established an adequate organizational design for their credit risk management system and have implemented a proper communication system . However, smaller institutions still maintain a more simplified risk management system and, consequently, a small team dedicated to credit risk management. Nevertheless, as expected, the credit risk culture has become a core issue for many financial institutions , and as a consequence, the role of the CRO within the bank’s organization is designed to bear increasing responsibilities to ensure the effectiveness of risk management and communication flows between top management and the bottom levels of the organization.

In Chap. 16 “Credit rating culture”, Giacomo De Laurentis presents a field research aiming at measuring rating culture of banks branch officers, professionals, and managers. The results highlight that mass media promote a misleading culture even among professionals. In general, it is difficult to find an adequate knowledge of the true and critical basic concepts behind credit ratings, as well as an adequate understanding of the key processes of rating assignment , rating quantification , and rating validation related to bank internal rating systems.

Alessandro Mechelli and Riccardo Cimini, in Chap. 17 “ Accounting conservatism and risk culture”, study the relationships between accounting conservatism, measured by the price-to-book ratio , and bank solidity, i.e., the tangible common equity as a percentage of total assets . Both variables have a close relation with risk culture, and they reflect the attitude of the risk manager to select the most proper bank capital to absorb losses due to risks manifestation. The results show that banks with a solid risk culture express a lower demand for conservatism.

In Chap. 18 “Auditing risk culture”, Fabio Arnaboldi and Caterina Vasciaveo develop an audit approach for assessing risk culture based on the 91 indicators. This chapter covers the terms of the mandate assigned to the internal auditing function by the board of directors , the perimeter of the risk culture framework, the main audit techniques aimed at evaluating risk culture and reporting structure and content.

The volume draws a picture of risk culture that turns out to be very articulate and still in rapid evolution. A “general theory” on risk culture is maybe not yet available, but the way forward has been mapped out. The concept of “good culture” has been well defined, although it has to be further developed based on the expectations of various bank stakeholders and the differences among business models. Empirical evidence should be interpreted cautiously because risk culture is a delicate and complex phenomenon. For this reason, the correct measurement of risk culture is a distant goal yet to be achieved. And the impact of a sound risk culture on bank performance cannot be unequivocally assessed. Culture can thus not yet be satisfactorily “priced”. When this will occur, the theory will step forward as well. Banks are undergoing a significant evolution of their risk cultures, being at times protagonists of this change. Awareness has increased, but all key players shall also acknowledge that a change in bank culture might be appropriate and convenient as well. Supervisors could benefit, and the financial system as well, from the attention that is being given to risk culture in banks, especially, if they find the right balance between guidelines and rules and banks autonomy in pursuing them, toward an explicit recognition, in terms of regulatory requirements , of the “ cultural wealth” of the individual banks. To reach this goal, supervisory authorities must be ready to investigate their own risk culture, which represents a further key issue influencing the effectiveness of cooperation and relationships between the various regulators and supervisors and the supervised entities as well.

In conclusion, we believe that risk culture is an extremely interesting and fascinating topic affecting the future evolution of the financial system. We are confident that our book provides many answers and food for thought, it is rich in analysis and proposals, but nevertheless raises some major questions which might stimulate further debate and research efforts on the subject.

Last but not least, we would like to thank all the authors for putting an outstanding effort and passion in their work and, especially, for being so patient with us (meeting all deadlines and our requests for changes). We would like also to thank Vladimiro Marini for his great assistance in helping us to meet the editorial tasks.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Carretta, A., Fiordelisi, F., Schwizer, P. (2017). Introduction. In: Risk Culture in Banking. Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Banking and Financial Institutions. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57592-6_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57592-6_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-57591-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-57592-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)