Abstract

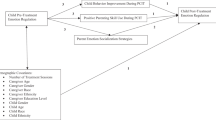

With a growing body of literature demonstrating the link between parent emotion socialization (the way in which parents model, react to, or teach children about emotions) and children’s emotional competence, there is an increasing interest in identifying the determinants of parent emotion socialization. Stress and the way parents regulate their emotional responses to stress are understood to play a significant role in determining parents’ capacity to socialize children’s emotional learning in positive ways. When parents have difficulty managing their own emotional responses (e.g., under conditions of high stress), their efforts to parent effectively and socialize their children’s emotional learning can be compromised. In this chapter, we review the empirical literature that has explored the relationship between stress, parent functioning (specifically parent’s own emotion awareness, regulation, and mental health), parent emotion socialization (especially emotion coaching) and children’s emotional, social, and behavioral functioning. In doing so, we consider how problematic ways of coping with stress are implicated in mental health difficulties and affect parents’ responsiveness to interventions. Then, we outline how we have targeted parent emotion regulation in our emotion socialization parenting program (Tuning in to Kids) that provides parents with skills to cope with stress more effectively. Finally, using data from our previously published intervention trials we reanalyze whether parent emotion awareness, regulation, and mental health are determinants of how well parents respond to this parenting program.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Emotion regulation

- Stress

- Parenting

- Emotion socialization

- Emotion coaching

- Family of origin

- Parent training

- Intervention

Parenting is demanding, challenging, and emotionally taxing leaving parents vulnerable to feeling stressed and reactive. Parents are regularly faced with the complex task of remaining calm in the face of a distressed or dysregulated child, while at the same time trying to regulate the child’s emotion, problem solve, and/or engage in limit setting (Rutherford, Wallace, Laurent, & Mayes, 2015). If parents face additional stresses (e.g., mental health difficulties, relationship difficulties, financial, or work-related stresses), their own emotions can overwhelm them, making it difficult to respond to their children calmly and in emotionally supportive ways. Further, juggling these demands may be particularly challenging when children are highly emotionally dysregulated (see Chap. 11 by Crnic & Ross for further discussion), heightening the need for parents to manage their own emotions while at the same time teaching their children to understand and regulate their emotions. Substantial evidence has demonstrated that parenting programs can improve the functioning of parents and children, although for parents with difficulties regulating their own emotions, the benefits of such programs have been found to be much weaker (Maliken & Katz, 2013). Efforts to improve parent emotion regulation may, therefore, enhance the impact of parenting interventions or improve the benefits for those who might struggle with high levels of stress and be less receptive to learning new parenting skills.

In this chapter, we explore how parents’ capacities to cope with stress and manage their own emotions affect their ability to respond in emotionally supportive and helpful ways with their children. We review the literature about what is known about the relationship between stress, parent emotion regulation, parent mental health difficulties, and parent emotion socialization (i.e., parental modeling of emotional expression, reactions to, and coaching children about emotions). We then outline how we have targeted parents’ capacity to respond to stress and learn effective emotion regulation in our Tuning in to Kids (TIK) and Tuning in to Teens (TINT) parenting programs (thereafter referred to as TIK). TIK teaches parents emotion coaching where parents scaffold children’s learning about emotions within a supportive, emotionally accepting relationship (Gottman & DeClaire, 1997). In order to teach parents emotion coaching, we have dedicated significant efforts to helping parents regulate their own emotions that occur either in response to their own life stressors or the challenges of parenting. While describing how we have targeted parent emotion regulation, we also propose some theoretical mechanisms by which learning and change might be occurring. Finally, we reexamine some of our previously published intervention efficacy studies of TIK and TINT to look at the influence of parent emotion regulation on intervention outcomes. In doing this, we aim to extend what is known about how parent emotion regulation impacts parent emotion socialization through the lens of a parenting program.

The Role of Parent Emotion Regulation in Emotion Socialization

Emotion socialization theory (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Halberstadt, Denham, & Dunsmore, 2001; Katz, Maliken, & Stettler, 2012; Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007) argues that parent emotion regulation is related to the development of children’s emotion competence via a number of mechanisms, including that parents model adaptive emotion regulation and are then able to respond supportively when children are emotional. Supportive responding involves parents’ ability to recognize their child’s emotions, respond by acknowledging and validating their child’s emotional experience, talk about emotions, and assist their child to understand and regulate their emotions (i.e., emotion coaching). These aspects of emotion socialization are associated with children having better emotion competence, social functioning, behavior, and academic functioning (Eisenberg et al., 1998; Katz et al., 2012; Morris et al., 2011; Perlman, Camras, & Pelphrey, 2008; Wong, McElwain, & Halberstadt, 2009). Conversely, when parents are unsupportive or emotionally dismissive in response to emotions, their children are more likely to have poorer emotional competence and higher levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior difficulties (Garner, Dunsmore, & Southam-Gerrow, 2008; Raver & Spagnola, 2002; Shipman et al., 2007; Suveg et al., 2008). During times of stress, parents’ and children’s physiological and psychological reactions can trigger strong emotional responses which may be attenuated or exacerbated by parents’ emotion socialization responses (Buck, 1984; Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1997).

When parents experience mental health difficulties, sadness or loneliness, fatigue and sleep deprivation, illness, child behavior problems, or other stressful life events, their ability to regulate their own and their child’s emotions is readily compromised (Maliken & Katz, 2013; Williford, Calkins, & Keane, 2007). Indeed, parental emotional dysregulation and psychopathology have been consistently linked with unsupportive parenting practices and behavioral and emotional difficulties in children (Zahn-Waxler, Duggal, & Gruber, 2002). Parents with heightened stress sensitivity due to genetic factors, growing up in a stressful environment, or preexisting mental health difficulties may be particularly at risk of excessive reactivity when faced with parenting stress (Laurent, 2014; Platt, Williams, Ginsburg, Williams, & Ginsburg, 2016). For example, Platt et al. (2016) found that current levels of parenting stress, parent–child dysfunctional interactions, and parents who engaged in ‘anxious rearing,’ mediated the relationship between stressful life events and child anxiety. A recent study (Breaux, Harvey, & Lugo-Candelas, 2015) that examined the relation between parents’ psychopathology symptoms and emotion socialization behaviors found higher levels of psychopathology were related to more unsupportive reactions to children’s negative affect. Similarly, when mothers with clinical levels of depression or anxiety have been compared to normal controls, they have been found to have fewer and less effective emotion regulation strategies and greater difficulties in communication and affective involvement (Hughes & Gullone, 2008; Psychogiou & Parry, 2014). Limited self-awareness and regulation of emotion are thought to underlie many forms of psychopathology (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010), and difficulties with attentional/behavioral regulation in parents can increase their tendency to engage in unsupportive or harsh parenting behaviors (Dix & Meuniera, 2009; Maliken & Katz, 2013). In turn, when either the parent or the child has difficulties with self-regulation and parents responses are unsupportive or harsh, emotions are likely to escalate for both the parent and the child (see Chap. 8 by Finegood & Blair): Yet, it is especially during periods of heightened stress that parents need to be able to regulate their own emotions and use supportive responses to buffer children from the negative impact of stress (Platt et al., 2016).

To date, only a few studies have directly investigated parental difficulties in emotion regulation as a mediator or predictor of parent outcomes in order to understand how stress, emotion dysregulation, and parenting of children’s emotions interact (Buck, 1984; Kehoe, Havighurst, & Harley, 2014a, 2015; Mazursky-Horowitz et al., 2015). During periods of stress, difficulties in emotion regulation may make it harder for parents to engage in supportive emotion socialization practices for several reasons. When parents with poor emotion regulation experience high levels of negative affect either in response to stressors, their own mental health difficulties, or due to their child’s emotional dysregulation, they may feel overwhelmed or ‘flooded,’ increasing their likelihood of withdrawal or expression of negative emotions in a dysregulated manner, resulting in neglecting, reactive or hostile discipline practices (Bariola, Gullone, & Hughes, 2011; Katz & Gottman, 1991; Lorber, Mitnick, & Slep, 2015; Mence et al., 2014). For example, Lorber et al. (2015) found that mothers of toddlers who felt flooded by their child’s behavior during discipline encounters experienced more negative emotion, showed increased heart rate reactivity and vagal withdrawal (viewed as poor emotion regulation), and this was related to parents’ over-reactive and harsh discipline responses. Jackson and Arlegui (2016) found that heightened negative affect hinders the ability of a person to detect someone else’s mood change. In addition, parents who report limited access to emotion regulation strategies have reported impulse control difficulties, lower acceptance of emotions (Gratz & Roemer, 2004), and increased likelihood of engaging in punishing or neglecting responses to their child’s emotion expression (Buckholdt, Parra, & Jobe-Shields, 2010).

Excessive down-regulation or not showing emotion (i.e., suppression) has also been found to contribute to problems in parenting. Suppression of negative emotions has been found to be related to lower parental positive expressiveness (Hughes & Gullone, 2010), lower use of supportive strategies (problem focused, encouraging of emotion expression, greater positive expressivity), and greater likelihood that the parent would engage in unsupportive parenting (matching the child’s distress, negative expressiveness) (Meyer, Raikes, Virmani, Waters, & Thompson, 2014). Maladaptive emotion regulation such as suppression of emotions tends to increase and prolong negative emotion arousal (Gross & John, 2003). In turn, heightened emotional dysregulation (or suppression) in the parent may make it difficult for them to access strategies to constructively manage feelings when solving emotional problems (Maliken & Katz, 2013), and may result in parents’ escalating children’s negative emotions (Burke, Pardini, & Loeber, 2008; Sheeber et al., 2011), or harsh over-reactive parenting (Lorber & O’Leary, 2005). In one of our recent studies with parents of preadolescents, parents’ self-reported difficulties in emotion awareness and regulation were related to parents’ greater use of emotion dismissing strategies with their child (parent and youth-reported), such as responding by overriding, punishing, or matching (i.e., become angry when the child is angry; Kehoe, Havighurst, & Harley, 2014b). Other studies have found similar results. For example, parents’ lower use of cognitive reappraisal strategies (considered maladaptive) has been associated with higher parental negative expressiveness (Hughes & Gullone, 2010), and parents who express higher levels of negative affect have been found to be less likely to respond supportively to their adolescents’ expression of negative emotions (Stocker, Richmond, Rhoades, & Kiang, 2007). Other studies conducted with adults have also found suppressing emotions to be related to poorer outcomes in adults, such as greater anxiety, impaired memory, poorer immune system functioning, and psychological stress (Gross, 2002; Gross & John, 2003; Lynch, Robins, Morse, & Krause, 2001).

Parent emotion awareness also plays an important role in parent’s emotion regulation and emotion socialization responses. When parents have deficits in awareness of their own or others emotions, this may impact how they cope with stress and their responsiveness to their children further exacerbating the negative emotions occurring in a situation (Gohm & Clore, 2002; Halberstadt et al., 2001). If parents are unable to recognize emotions (especially lower intensity emotions), their ability to regulate emotions is likely to be compromised, with lower awareness or clarity with emotions having been found to be related to difficulties in emotion regulation (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). Further, parents who have difficulties identifying emotions in themselves or who are less accepting of their own emotions may be less likely to engage in supportive emotion socialization practices, which requires talking about feelings (Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995; Yap, Allen, Leve, & Katz, 2008). When emotions are identified at a lower intensity, it is easier for parents to implement emotion regulation strategies (Linehan, Bohus, & Thomas, 2007) and more likely that they will be better equipped to deal with the source of stress (Gohm & Clore, 2002). Finally, it is also possible that when parents are emotionally overwhelmed during high levels of stress, their emotion awareness and ability to engage in perspective taking are compromised due to limited access to executive functions (Suchy, 2011).

These findings suggest that prevention and intervention programs for parents who experience difficulties with emotion awareness and regulation or mental health difficulties may be enhanced by incorporating a focus on how parents manage their own emotions in addition to strategies for parenting. Parental difficulties in emotion regulation have been found to have a negative impact on intervention effectiveness as well as influencing program attendance (Assemany & McIntosh, 2002; Maliken & Katz, 2013). For example, the presence of parental anxiety or depression has been found to limit the effectiveness of treatment on child/youth anxiety outcomes (Cobham, Dadds, & Spence, 1998; Garber et al., 2009; Kendall, Gosch, Hudson, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008). When parents feel overwhelmed by their own difficulties, they may not feel up to attending a session, or when they do attend may find it harder to focus on learning new skills. Poorer session attendance may result in parents missing important information or lacking confidence to implement the skills. The presence of higher levels of depression, anxiety, and/or stress has been found to be related to lower attendance and higher dropout rates in parenting programs, and interferes with skill acquisition as well as skill implementation (Maliken & Katz, 2013; Zubrick et al., 2005). Treatment of these mental health conditions and/or targeting parent emotion awareness and regulation may assist with program attendance and acquisition of new parenting skills.

Given that parent mental health difficulties are a risk factor for maladaptive parenting, a more parsimonious (or ‘transdiagnostic’) approach to treatment or prevention by targeting common higher order factors (e.g., managing stress and emotion regulation) that underlie emotional disorders and maladaptive parenting would seem to be important (Aldao et al., 2010; Weersing, Rozenman, Maher-Bridge, & Campo, 2012). When parents are able to acquire skills that enable them to increase their awareness and regulation of emotions and implement strategies to manage stress, they are likely to be in a better position to both learn and implement supportive parenting practices. This approach has been taken in a number of interventions including our own work.

Interventions Targeting Parent Emotion Regulation

Published accounts of interventions that target parent emotion regulation and the way parents manage stress in order to improve parenting are limited. A review by Katz et al. (2012) highlighted that the translation of emotion socialization theory from research into practice is in its infancy, with very few parenting interventions specifically targeting all aspects of emotion socialization. A number of interventions for parents are, however, beginning to include components that focus on teaching parents skills in emotional regulation. These can be grouped into three approaches: (1) behavioral parenting programs where the main focus is on teaching behavior management strategies but with added components that target aspects of parent emotion regulation; (2) mindfulness-based interventions that assist parents to manage stress by teaching the principles of mindfulness, such as present-moment awareness, nonjudgment, and compassion to reduce emotional reactivity and improve emotion regulation; and (3) emotion-focused programs which teach parents skills required for adaptive emotion socialization and include components targeting parent emotion awareness and regulation.

Behavioral parenting programs such as Triple P (Sanders & Markie-Dadds, 1996) or The Incredible Years (Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2007) primarily focus on teaching parenting skills to manage children’s behaviors and less on teaching parents how to recognize, understand, and manage their own or their child’s emotions. These programs have been found effective in improving parent mental health as well as parenting discipline practices and involvement (Furlong et al., 2012). However, up to one-third of families who attend behavioral parenting programs do not benefit (Brestan & Eyberg, 1998; Taylor & Biglan, 1998). This may be because of other stressors occurring for parents (e.g., low income, single parenting, marital conflict, parent emotion regulation difficulties, high levels of stressful life events) that make it difficult for parents to learn the new skills. Behavioral programs have also been found to be less effective when there are parent–child attachment-related difficulties (Maliken & Katz, 2013; Scott & Dadds, 2009; Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1990) and are less effective with older children and adolescents (e.g., Burke, Brennan, & Cann, 2012; Ralph & Sanders, 2006). It is therefore important, and in keeping with a transdiagnostic approach, to target broader factors such as the way parents manage their own and their child’s emotions as a way of reducing the effects of stress and assist in building parenting skills.

To date, only a handful of studies have been conducted that have investigated the effects of adding parent emotion regulation components to behavioral parenting programs (e.g., Lenze, Pautsch, & Luby, 2011; Luby, Lenze, & Tillman, 2012; Sanders, Markie-Dadds, Tully, & Bor, 2000). For example, Sanders and colleagues (2000) investigated the value of including strategies to help reduce marital conflict (i.e., communication skills) and stress-coping skills as additional components to a behavioral parenting program. These additional components resulted in reduced observed negative child behaviors compared to teaching standard behavioral management skills alone; however, these differences were no longer present at 1-year follow-up. Other studies that were reviewed have only had very small sample sizes, and so, it is not yet clear whether there are benefits of adding parent emotion regulation components to a behavioral parenting program.

Mindfulness parenting interventions target how the parent responds to stress by improving emotion regulation skills and managing reactivity (e.g., Coatsworth, Duncan, Greenberg, & Nix, 2010). Duncan, Coatsworth, and Greenberg 2009) proposed five dimensions of mindful parenting which are thought to foster specific parenting skills and promote more responsive parenting: (a) listening with full attention (which assists the parent in accurately perceiving the child’s verbal and behavioral expressions); (b) nonjudgmental acceptance of self and child (reduces unrealistic expectations of self and the child and increases parenting self-efficacy); (c) emotional awareness of self and child (increases responsiveness to the child’s emotions and reduces parental negative emotions); (d) self-regulation in the parenting relationship (better emotion regulation and less over-reactive automatic discipline); and (e) compassion for self and child (fosters less self-blame and positive affection, reduces negative affect). In addition, the process of ‘decentering’ (i.e., pausing before reacting and noting that feelings are just feelings) is thought to facilitate parents’ ability to endure strong emotions that are so often elicited during parent–child interactions and when encountering stress (Duncan et al., 2009). These components of parenting are very similar to key elements of emotion socialization. Parenting interventions that have incorporated mindfulness have been found to improve parenting and the parent–child relationship (Altmaier & Maloney, 2007; Benn, Akiva, Arel, & Roeser, 2012), as well as reducing youth externalizing difficulties (Bögels, Hoogstad, van Dun, de Schutter, & Restifo, 2008). A study with at-risk youth (aged 10–14 years) provided preliminary evidence that teaching children and parents mindfulness (e.g., awareness and acceptance of emotions) was effective in increasing parents’ emotion awareness and regulation as well as enhancing parent–youth relationships (Coatsworth et al., 2010).

There are a handful of emotion-focused programs that directly focus on parent emotion regulation as well as teaching emotion coaching parenting. Short and colleagues (2014) conducted a pilot study of an emotion-focused intervention delivered to incarcerated mothers prior to reunification with their children after prison. Of the 47 parents who all attended a behavioral parenting program, 29 received an additional Emotions Program while 18 did not. The Emotions Program (15 × 2 h sessions over 8 weeks) was based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan et al., 2007) and the Tuning in to Kids parenting program (Havighurst & Harley, 2007), with nine sessions focused on teaching mothers’ emotion regulation and six sessions targeting emotion coaching skills. The Emotions Program was found to be related to significantly less criminal behavior post-release compared to those mothers who did not attend the program. However, mothers in both conditions showed improvements in emotion regulation, emotion socialization, and mental health. Moretti and Obsuth (2009) published outcomes of a 10-session attachment-based parenting intervention which included a focus on parent emotion regulation and empathy as well as improving the parent–youth relationship. In a sample of parents of adolescents (aged 12–16 years) at risk of aggressive behavior, outcomes were significant reductions in parent-reported youth internalizing and externalizing behavior difficulties as well as improved affect regulation in youth.

Our own Tuning in to Kids (TIK) parenting program aims to improve the emotion socialization of children and also targets parent emotion awareness, regulation and stress management as key parts of the intervention (Havighurst & Harley, 2007). TIK teaches parents emotion coaching skills; that is how to recognize, understand, and manage their own and their children’s emotions. The emotion coaching style was identified by Gottman, Katz and Hooven (1996) and includes five steps (Gottman & DeClaire, 1997). When children experience emotions, parents: (1) notice the emotion, (2) see this as an opportunity for intimacy and teaching; (3) communicate an understanding and acceptance of the emotion; (4) assist the child to use words to describe how they feel; and (5) if necessary, assist with problem solving and/or set limits around behavior (Gottman & DeClaire, 1997). The program focuses on increasing skills required for each of the five steps, including understanding where beliefs about emotions come from (e.g., family of origin experience) and how these experiences influence attitudes and responses to emotions. TIK aims to prevent problems developing in children, promote emotional competence (in parents and children), and when present, reduce and treat problems with children’s emotional and behavioral functioning. TIK is a six-session group program that is extended over a longer duration for parents with more complex needs. The program, first developed for parents of preschoolers, has been adapted and extended for fathers as well as for parents of toddlers/primary aged children/adolescents, and for parents of children who have experienced trauma or have difficulties with anxiety and behavior problems. The TIK program and its variants (e.g., Tuning in to Teens) have been evaluated in a series of randomized controlled trials, demonstrating the program’s positive impact on parenting as well as on child emotional competence and other social and behavioral outcomes. To date, these studies have shown the program to be beneficial for reducing parent’s emotion dismissing, increasing empathy and emotion coaching, improving parenting confidence, improving children’s emotion competencies, and reducing child/adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (Duncombe et al., 2014; Havighurst et al., 2015; Havighurst, Kehoe, & Harley, 2015; Havighurst et al., 2013; Havighurst, Wilson, Harley, Prior, & Kehoe, 2010; Kehoe et al., 2014b; Lauw, Havighurst, Wilson, Harley, & Northam, 2014; Wilson, Havighurst, & Harley, 2012, 2014; Wilson, Havighurst, Kehoe, & Harley, 2016). Importantly, the extension of this work to other independent research groups will help to validate the effectiveness of TIK and Tuning in to Teens across cultures and for more varied populations. Current trials are underway in Norway, Germany, Iran and the USA.

Components of TIK that Target Parent Emotion Regulation

We now turn to describe the Tuning in to Kids approach in more detail in order to demonstrate how specific emotion-related parenting skills are targeted and how these may be particularly important for parents when their capacity to regulate emotions is compromised, such as during times of stress. Throughout the TIK program we consider that there is a parallel process between parents developing their own emotion regulation and teaching their children about emotions. We use four main approaches for improving parent’s ability to manage emotions effectively, including:

-

1.

Teaching parents emotion awareness

-

2.

Examining the influence of parents’ family of origin on their emotion competence and their meta-emotion philosophy (beliefs and reactions to emotions)

-

3.

Building parents’ emotional self-care, and

-

4.

Teaching parents’ emotion regulation skills.

In our experience of running many parenting groups using the TIK suite of programs, all four of these components are important to target in order to change how parents regulate their emotions which in turn impacts their parenting around emotions with their children. Further, different strategies work for different parents, and we have found having a selection of approaches that dovetail toward a similar common theme (regulating emotions) is important. Psycho-education and exercises about parent’s own emotion regulation are delivered in a nonthreatening way in order to reduce possible parental defensiveness. We found in the early stages of developing TIK that it was possible to ‘scare parents off’ if they thought, ‘this is all about me!’, and so while we gently introduce the idea that parents’ emotions shape children’s emotional learning, we mainly begin to target parents’ emotion awareness/regulation from session 2 of the program onward. The following outlines the different exercises that we use in TIK to build parent emotion regulation along with proposed mechanisms via which these skills and intervention processes may work.

Parent Emotion Awareness. Emotion awareness and understanding provides the foundation for healthy regulation of emotions and includes the capacity to notice and accurately identify one’s own and other’s emotions (Halberstadt et al., 2001). In TIK, there is a focus on building parents’ and children’s emotion awareness in order to facilitate emotion understanding and regulation. Learning is scaffolded in a step-by-step approach across the six sessions, beginning with asking parents to notice emotions in their child (homework in session 1) and then in session 2 to attempt to label these emotions via reflecting the feeling to the child (I wonder if you are a little sad right now?). Session 2 of the program also more formally builds emotion awareness for parents in a warm-up exercise called ‘The Bear Stickers’ where parents choose a sticker to represent an emotion they have had throughout the week. They are then asked (as a whole group or in a discussion with one other parent participant) to name the emotion, describe what led to them feeling this way, locate where they feel this emotion in their body, consider the thoughts that accompanied the emotion and (in some variants of the program) consider how they felt about having this emotion (meta-emotion beliefs). This exercise is typically very illuminating with many parents having difficulty labeling their own emotions. Reasons for this may be because they are not accustomed to sharing this information, because they have poor emotion awareness and have never paid attention to their own emotions in a conscious way, may find it difficult to locate emotions in their body, or may have never considered how they think/feel about having emotions. This exercise provides a framework for future discussions about emotion awareness in the program as well as providing parents with a new template for self-reflection about emotions and a technique for how emotions might be explored with their child.

Considerable attention is paid in the program to increasing parents’ awareness of their child’s emotions with reciprocal benefits for the parents’ own emotional learning. Parental awareness of their child’s anger, sadness, and fear has been found to decline from preschool to early adolescence (Stettler & Katz, 2014). Many parents struggle to identify their child’s emotions, remaining focused on misbehaviors or their own overwhelmed feelings. Sometimes children have to really escalate their emotions for their parent to notice. The TIK program attempts to help parents recognize emotions via noticing facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice and identifying a time when their child is more likely to want to talk about their emotions (such as while driving in the car or at bed time). Through this learning many parents report that the skills are mutually beneficial for them.

Additionally, in session 3 TIK uses an activity called ‘The emotion detective,’ which involves giving parents a list of common child (or adolescent) scenarios/situations and asking them to find a similar adult equivalent and to identify how they would feel in this situation. This assists parents to ‘step into their child’s shoes’ and encourages perspective taking as well as awareness of emotions that the child might be experiencing. Helping parents to engage in perspective taking may not only help to identify their child’s feeling but also assist the parent to remain less reactive (Webb, Miles, & Sheeran, 2012) and respond more supportively, thereby inherently being emotionally regulating. In turn, having feelings validated may help to lower the intensity and duration of the child’s emotional experiences. Together, this allows the child to process emotions by focusing on their feelings rather than internalizing or engaging in dysregulated behaviors, while also reducing parenting stress and the experience of negative emotions for the parent (Gottman et al., 1997; Schutte et al., 2001; Shenk & Fruzzetti, 2011).

Finally, to further build parent (and child) emotion awareness we use emotion faces posters (which include an emotion face plus an emotion label underneath), ask parents to talk with their children about emotions, and encourage parents to read emotion-focused books to their children. In addition, a list of 100 emotion words under the headings of happy, sad, angry, and scared is given to parents to encourage them to use a wider emotion vocabulary. Many parents who attend our programs will say that they do not know the meaning of some of the emotion words on our feeling faces posters or emotions lists and this often becomes a focus of teaching by program facilitators. Increasing children’s emotion vocabulary has been found to assist them with emotion regulation (Saarni, 1999), and we believe it also assists parents with the same skills.

We hypothesize that helping parents to become aware of and name emotions (step 1 and step 4 of emotion coaching) provides parents with an anchor for present-moment awareness, like the focusing on breath does in a mindfulness meditation (Hill & Updegraff, 2012). This allows parents to shift to thinking about how they or their child are feeling, rather than suppressing emotions or becoming reactive. Often parents report being calmer by just trying to recognize emotions. The focus on awareness of emotions also allows parents to be more present during interactions and enhances empathic responding, facilitating greater intimacy and connection (Block-Lerner, Adair, Plumb, Rhatigan, & Orsillo, 2007; Yap, Allen, & Ladouceur, 2008) consistent with mindfulness parenting interventions (Duncan et al., 2009). By increasing awareness of emotions and attention to the child’s emotional response, ineffective patterns of interactions that have become automatized (i.e., are largely unconscious) can be recognized and changed (Bargh & Ferguson, 2000; Dumas, 2005). Awareness of one’s own parenting behavior and altering automatic responses are also key components of other effective parenting interventions such as Triple P (Sanders et al., 2000) and the Incredible Years (Webster-Stratton & Reid, 2007).

Family of Origin and Meta-Emotion Philosophy

Responding to challenging behaviors and intense emotions in one’s children can lead to strong feelings in parents (e.g., powerlessness, guilt, helplessness, anger, rage, sadness, embarrassment, shame) and may remind them of their family of origin and past experiences (see Chapter 10 by Mileva-Seitz & Fleming for discussion on the intergenerational effects of parenting). We primarily learn about emotions from those with whom we have close relationships (such as siblings or peers) and/or who play a caregiving role in childhood—experiences which shape our attitudes and reactions to emotions (Dunn, Brown, & Beardsall, 1991). Identification of the messages parents received about emotions during their childhood (e.g., anger must not be expressed; crying and showing sadness is weak; it is silly to worry) will influence their capacity to remain calm and responsive when faced with the stress of parenting and strong emotions in themselves or their children. Therefore, a critical way in which we address parents’ capacity to regulate emotions that arise during parent–child interactions is by exploring their experiences in their own family of origin with emotions in order to understand how these have shaped their beliefs and reactions to emotions in themselves and others. This is also known as Meta-Emotion Philosophy (Gottman et al., 1997).

There is now substantial evidence linking the intergenerational transmission of attachment patterns to parents’ capacity to regulate emotions and subsequently to their emotional responsiveness to their children (e.g., Beijersbergen, Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2012; Kim, Capaldi, Pears, Kerr, & Owen, 2009; Schore & Schore, 2008). Schore (2008) highlights that early attachment relationships provide the basis for adaptive (and maladaptive) regulation of emotion, and shapes the way the brain processes emotions in future relationships. Other research has also highlighted that parents’ family of origin emotional expressiveness influences parents’ current emotional expressiveness and emotion-scaffolding behaviors (Baker & Crnic, 2005): parents who experienced more negative emotional expressivity in their family of origin were less likely to engage in emotion-scaffolding behaviors with their toddlers. In our TIK groups, many parents will say that avoidant, minimizing, or punitive responses to emotions in their family of origin were not helpful and continue to cause them stress or difficulty in the present day, both as an individual and as a parent.

Exploration of family of origin experiences, memories, and meta-emotion occurs slowly and carefully in TIK, allowing parents the option to opt out or not to speak when group or pair discussions focus on these topics. The depth of exploration of family of origin and meta-emotion philosophy is determined by the facilitator’s assessment of how capable the group is in talking about this topic as well as the facilitator’s skill and competence (i.e., less experienced facilitators might not go into this in much depth; experienced therapists delivering the program in clinical settings might explore this at length across an extended eight-session version of the program). This process of exploring beliefs about emotions and a person’s history with respect to emotions is (in our experience) critical to assisting parents to learn emotion coaching. It increases awareness and insight and reduces parental reactivity (both in how they respond to stress and in parenting), creating the calm and focus necessary for a parent to adopt a child-centered approach when responding to emotions in the child. Others have also found this process to be important for change (e.g., Greenberg & Pascual-Leone, 2006; Lane, Ryan, Nadel, & Greenberg, 2015). To alter intergenerational patterns of emotionally rejecting parenting it is necessary to develop connected relationships, learn emotional and cognitive regulation skills, and experience a process of working through past experiences (Leerkes & Crockenberg, 2006).

There are a number of reasons why addressing family of origin experiences and resultant meta-emotion beliefs may be helpful. Parents’ histories with emotions are likely to impact their reactions to emotions by triggering past memories and engaging unhelpful beliefs or schema (Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2006). For example, if a parent has experienced rejection as a child, when similar emotions are triggered during interactions with their own child (as they so often can be with an autonomy-seeking toddler or an individuating teen), parents may feel very hurt by their own child’s need for autonomy (perceived as rejection) and may be more likely to experience heightened negative affect and beliefs that activate harsh, rejecting responses or withdrawal. This process of asking parents to reflect on and consider their family of origin surrounding emotional experiences is akin to the processes involved in schema-focused or emotion-focused psychotherapy where changes are thought to occur by accessing past experiences and evoking the emotions consistent with these memories in order to work through and alter automatic dysfunctional patterns of thinking, feeling, behaving, and interacting (Greenberg & Safran, 1989). Through this therapeutic process, intense automatic reactions are reduced because the emotion no longer activates the (often unconsciously) remembered past emotional experience. Reflection on past (emotional) familial experiences is also a core component of psychoanalytic psychotherapy and is seen as integral to reducing the influence of defenses (Freud, 1896). As a brief six- to eight-session group program TIK does not have sufficient time or an established agenda for this degree of therapeutic work. However, the group process often enables parents to reflect, consider, and access past formative experiences with emotions in order to separate out what is current and what is past as well as to provide them with new scripts/reappraisals for responding to emotions in themselves and their children. Parents’ emotion regulation improves as a consequence of this by reducing automatic responses of anger or distress that may occur when their children are emotional or they are experiencing stress in their lives.

Emotional Self-Care. Parenting is often a highly stressful experience and occurs simultaneously alongside many other personal, relational, professional, and public demands (see Chap. 3 by Nomaguchi & Milkie). It is, therefore, critical for parents to develop skills in managing stress. Self-care refers to behaviors that maintain and promote physical and emotional well-being, including factors such as sleep, exercise, use of social support, emotion regulation strategies, and mindfulness practices (Myers et al., 2012; Quick, Wright, Adkins, Nelson, & Quick, 2013; Salmon 2001). As such, self-care activities can include a daily mediation practice, regular time for exercise, slow breathing, yoga, taking a hot bath, or just sitting down for a cup of tea. The regular practice of self-care helps to reduce stress as well as to prevent more reactive parenting; others have also found self-care strategies useful in mental health and parenting interventions (e.g., Linehan et al., 2007; Salmon 2001). In TIK, parents are asked to notice when they feel their emotions rising. Regularly tuning into lower intensity emotion arousal, such as mild frustration or stress, and considering emotional self-care at this time allows the parent to be calmer and enable them to be more aware of and able to assist their child. Parents often do not recognize the importance of self-care and report feeling guilty and selfish about taking this time. Others are impeded from using self-care because of limited resources. By exploring barriers to engaging in self-care, these beliefs can be addressed and parents can learn that looking after one’s own emotional well-being is an important proactive emotion regulation strategy to help manage the stress of parenting enabling the parent to be more emotionally responsive.

Emotion Regulation Skills. The development of skills in regulating emotions and managing stress is highly important for mental health and parenting (Aldao et al., 2010). We have found that if parents report that they are overwhelmed by stress and have limited access to emotion regulation strategies, they typically struggle to use emotion coaching successfully. The last sections of our chapter have highlighted that TIK recognizes that in order to be able to engage in empathic responding (which lies at the heart of emotion coaching), parents require good emotion awareness. If emotions are not able to be recognized, parents may miss the opportunity to respond. On the other hand, if a parent’s own emotional experience during an interaction with their child is strong and they are unable to regulate their heightened negative arousal and/or distress, they are more likely to respond in a self-focused rather than child-focused manner (Eisenberg, 2000). Therefore, key components of TIK are becoming aware of one’s own emotion regulation patterns and learning emotion regulation skills.

In TIK, we teach three main ways of regulating emotions that fall into the categories of pausing, calming, or releasing. In addition, we teach strategies which parents can use in advance (i.e., self-care) and ‘in the moment,’ with a specific focus on regulating anger, anxiety, and stress. ‘Building in a pause’ for parents is one of the simplest ‘in the moment’ techniques for parents to learn and is critical for reducing emotion reactivity. Parents are taught that during moments of ‘emotional flooding’ it is difficult to access cognitive strategies, and therefore, pausing can be more effective. Methods for building in a pause include running their hands under cold water, taking 10 slow deep breaths, stepping out of the room, paying attention to their senses (smell, colors, textures), having a sip of cold water, visualizing a red traffic light, or telling oneself to ‘STOP.’ The concept of ‘building in a pause’ helps parents to break from automatic reactions and engage in more child-centered parenting and is consistent with mindfulness techniques (Duncan et al., 2009; Linehan et al., 2007). Calming strategies may include parents breathing slowly, having some quiet time in their room, having a bath or a shower, or talking to someone who they find calming. These strategies are also consistent with anxiety management techniques used in cognitive behavioral therapy (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Hawton, Salkovskis, Kirk, & Clark, 1989). Emotional release activities include exercise, tensing and releasing different muscle groups, having a good cry, twisting a towel, or weeding the garden. These strategies are explored with parents to find those that uniquely fit with the parents’ preferred way of calming or releasing the physical aspects of emotions. Parents are also encouraged to use the calming and releasing activities preventatively as part of their self-care. Stress-releasing activities, such as tense and release exercises that enable a person to let go of physical tension and strong emotions occurring as part of the fight or flight response are also an effective component of cognitive behavioral therapy (Beck et al., 1979; Hawton et al., 1989).

Mindfulness techniques are taught in facilitator-led meditation/relaxation, and internet links are provided to a range of resources that can assist parents to learn new skills for calming their reactivity in advance (e.g., self-care). Parents are encouraged to use these ‘in the moment’ strategies when they are stressed and need to down-regulate their own emotional intensity (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation, breathing). Some of these techniques have also been found important in other emotion regulation-focused interventions for adults (e.g., mindfulness; Duncan et al., 2009; Linehan et al., 2007) and for children (e.g., the PAThS program; Greenberg, Kusche, Cook, & Quamma, 1995).

Lastly, we have found that teaching parents the five steps of emotion coaching outlined by Gottman and DeClaire (1997) helps them regulate their own emotions because they shift to a more child-centered approach to parenting where they go through five practical steps to approach the emotions that their child is experiencing. Instead of thinking ‘Oh, he is such a difficult child!’, ‘She is so out of control!’, ‘‘I can’t stand this!’, ‘Why does he have to ruin everything!’ (which contributes to parents’ emotions escalating), we encourage parents to view the emotional moment as an opportunity for connection and teaching. This is a form of cognitive reappraisal (Gross & Thompson, 2007), whereby the parent no longer sees the child’s emotions as overwhelming and as something to overcome or avoid, but instead sees that their child is struggling and develops some confidence as they work through each emotion coaching step. For example, ‘What is he/she feeling?’, ‘Can I teach him/her?’, ‘Can I label the emotion?’, ‘Can I empathize?’, ‘Can I breathe slowly and slow down my reactions until my child calms’: then, ‘what might we do to work through this situation?’ Helping parents dynamically adjust their responses in emotional moments enhances their ability to manage parenting stress, regulates their own emotions, and gives them tangible skills for responding to their child.

Does Parent Emotion Regulation Influence the Outcomes of Tuning into Kids/Teens?

In order to further examine the role of parent emotion regulation and coping with stress on parenting around children’s emotions, we reexamined some of our own data to see whether the TIK program was moderated by parent psychological distress or poor emotion regulation at baseline. In our first TIK efficacy trial we considered whether parents’ baseline difficulties in awareness and regulation, parents’ psychological distress, or parents baseline negative expressiveness moderated changes in parents’ emotion dismissing, emotion coaching, or empathy at six-month follow-up (Havighurst et al., 2010). With the exception of parents’ negative expressiveness, none of our other moderator analyses were statistically significant, suggesting that all intervention parents reported improvements in emotion socialization regardless of baseline functioning. Interestingly, parents’ baseline negative expressiveness did moderate the effect of TIK on parents’ emotion coaching at six-month follow-up (P = .012). Specifically, although all intervention parents showed significant improvements on emotion coaching, intervention parents with low negative expressiveness showed significantly greater improvements. It may be that low-level negative expressiveness in this sample was representative of a group of parents who were not aware of their emotions, or felt uncomfortable showing them. Learning skills in awareness and understanding of emotions may have enabled these families to be less dismissive of their own child’s emotion experience. Alternately, parents who were less negatively expressive may have been better able to learn the emotion coaching skills because they were not flooded by their own emotions.

For our study where TIK was delivered as part of a multi-systemic intervention to families where the 5–9 year old child was identified at risk for conduct disorder, i.e., top 7–8% of child behavior problems, we considered parents’ psychological distress (measured via DASS, a screening measure for stress, anxiety and depression; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) and parents’ baseline negative expressiveness as moderators of program effects on parents’ emotion dismissing, emotion coaching, or empathy (Havighurst et al., 2015). None of the three-way interactions were significant, indicating that the changes held for all intervention participants, regardless of baseline severity of parents psychological functioning. With this at-risk sample, TIK was also compared with a behavioral parenting program (Duncombe et al., 2014). In this study, TIK was found to be more effective in reducing child behavior problems than the behavioral parenting program for parents who had higher levels of emotional difficulties themselves. We hypothesized that this was because the program had a focus on emotion regulation for the parent providing an important set of skills for those parents who had poorer mental health.

We also investigated whether the impact of Tuning in to Teens (TINT) was moderated by parents’ baseline level of internalizing difficulties and problems with awareness and regulation of emotion (Kehoe, 2014; Kehoe et al., 2014b). Again, none of the moderator analyses were significant, indicating that regardless of baseline severity, a greater decrease in emotion dismissing and youth functioning (internalizing and externalizing difficulties) was reported by intervention parents and preadolescents, when compared to control participants.

These findings suggest that the positive outcomes from TIK and TINT are found with parents regardless of parents’ emotion regulation—both those low and high in emotion regulation prior to the intervention equally show improvements. One study suggests that parents with greater psychological difficulties may make greater progress in TIK than when using a behavioral parenting program perhaps because of the additional focus in TIK on parent emotion regulation helping parents to manage their own response to parenting stress as well as their own mental health.

Conclusion

Parents’ ability to manage stress and regulate their emotions has been found to be related to their capacity to respond to their children’s emotions. A review of the literature found that better parent emotion regulation has been found to be associated with more favorable emotion coaching and supportive response to children’s emotion socialization. The TIK parenting program which targets parent emotion socialization and parent’s own emotion regulation has a considerable focus on building emotion regulation through increasing emotion awareness, exploring family of origin and meta-emotion philosophy, increasing parent emotion self-care, and teaching specific emotion regulation skills, especially for managing anger, anxiety, and stress. These all play an important role in assisting parents to understand and regulate their own emotions thereby reducing the stress of parenting, contributing to a calmer family emotion climate, and enabling them to use the five steps of emotion coaching with their children. This transdiagnostic approach to intervention, which assists parents in their capacity to cope and improves parenting (and dually influences child outcomes), allows exploration of how parenting stress, emotion regulation, and child functioning are connected. This also allows greater consideration of how parenting interventions need to go beyond just a focus on how they respond to the child but also to engage parents in learning and applying skills in how they manage stress and their own emotional functioning. This combination is likely to produce the most powerful intervention outcomes.

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Altmaier, E., & Maloney, R. (2007). An initial evaluation of a mindful parenting program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(12), 1231–1238. doi:10.1002/jclp.20395

Assemany, A. E., & McIntosh, D. E. (2002). Negative treatment outcomes of behavioral parent training programs. Psychology in the Schools, 39(2), 209–219. doi:10.1002/pits.10032

Baker, J. K., & Crnic, K. A. (2005). The relation between mothers’ reports of family-of-origin expressiveness and their emotion-related parenting. Parenting: Science and Practice, 5(4), 333–346. doi:10.1207/s15327922par0504_2

Bargh, J. A., & Ferguson, M. J. (2000). Beyond behaviourism: On the automaticity of higher mental processes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 925–945. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.126.6.925

Bariola, E., Gullone, E., & Hughes, E. (2011). Child and adolescent emotion regulation: The role of parental emotion regulation and expression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0092-5

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guildford Press.

Beijersbergen, M. D., Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2012). Remaining or becoming secure: Parental sensitive support predicts attachment continuity from infancy to adolescence in a longitudinal adoption study. Developmental Psychology, 48(5), 1277–1282. doi:10.1037/a0027442

Benn, R., Akiva, T., Arel, S., & Roeser, R. W. (2012). Mindfulness training effects for parents and educators of children with special needs. Developmental Psychology, 48(5), 1476–1487. doi:10.1037/a0027537

Block-Lerner, J., Adair, C., Plumb, J. C., Rhatigan, D. L., & Orsillo, S. M. (2007). The case for mindfulness-based approaches in the cultivation of empathy: Does nonjudgmental, present-moment awareness increase capacity for perspective-taking and empathic concern? Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 33(4), 501–516. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2007.00034.x

Bögels, S., Hoogstad, B., van Dun, L., de Schutter, S., & Restifo, K. (2008). Mindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parents. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(02), 193–209. doi:10.1017/S1352465808004190

Breaux, R. P., Harvey, E. A., & Lugo-Candelas, C. I. (2015). The role of parent psychopathology in emotion socialization. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 1–13. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-0062-3

Brestan, E. V., & Eyberg, S. M. (1998). Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27, 180–189. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5

Buck, R. (1984). The communication of emotion. New York: Guilford.

Buckholdt, K. E., Parra, G. R., & Jobe-Shields, L. (2010). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism through which parental magnification of sadness increases risk for binge eating and limited control of eating behaviors. Eating Behaviors, 11, 122–126. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.10.003

Burke, K., Brennan, L., & Cann, W. (2012). Promoting protective factors for young adolescents: ABCD parenting young adolescents program randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescence, 35(5), 1315–1328. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.05.002

Burke, J. D., Pardini, D. A., & Loeber, R. (2008). Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(5), 679–692. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9219-7

Coatsworth, J. D., Duncan, L. G., Greenberg, M. T., & Nix, R. L. (2010). Changing parent’s mindfulness, child management skills and relationship quality with their youth: Results from a randomized pilot intervention trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 203–217. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9304-8

Cobham, V. E., Dadds, M. R., & Spence, S. H. (1998). The role of parental anxiety in the treatment of childhood anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(6), 893–905. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.66.6.893

Dix, T., & Meuniera, L. N. (2009). Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Developmental Review, 29(1), 45–68. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2008.11.002

Dumas, J. E. (2005). Mindfulness-based parent training: Strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 779–791. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_20

Duncan, L. G., Coatsworth, J. D., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). A model of mindful parenting: Implications for parent-child relationships and prevention research. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 255–270. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0046-3

Duncombe, M. E., Havighurst, S. S., Kehoe, C. E., Holland, K. M., Frankling, E., & Stargatt, R. (2014). Comparing an emotion- and a behavior-focused parenting program as part of a multi-systemic intervention for child conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.963855

Dunn, J., Brown, J., & Beardsall, L. (1991). Family talk about feeling states and children’s later understanding of others’ emotions. Developmental Psychology, 27(3), 448–455. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.27.3.448

Eisenberg, N. (2000). Empathy and sympathy. New York: Guilford Press.

Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., & Spinrad, T. L. (1998). Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry, 9(4), 241–273. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1

Freud, S. (1896). The Aetiology of Hysteria, Standard Edition, vol. 7: Hogarth Press.

Furlong, M., McGilloway, S., Bywater, T., Hutchings, J., Smith, S. M., & Donnelly, M. (2012). Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3–12 years. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008225.pub2

Garber, J., Clarke, G. N., Weersing, V. R., Beardslee, W. R., Brent, D. A., Gladstone, T. R. G., … & Iyengar, S. (2009). Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association (21), 2215–2224. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.788

Garner, P. W., Dunsmore, J. C., & Southam-Gerrow, M. (2008). Mother-child conversations about emotions: Linkages to child aggression and prosocial behavior. Social Development, 17(2), 259–277. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00424.x

Gohm, C. L., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in well-being, coping, and attributional style. Cognition and Emotion, 16(4), 495–518. doi:10.1080/02699930143000374

Gottman, J. M., & DeClaire, J. (1997). The heart of parenting: How to raise an emotionally intelligent child. London: Bloomsbury.

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1996). Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 243–268. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1997). Meta-emotion: How families communicate emotionally. Mahway, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. doi:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Greenberg, M. T., Kusche, C. A., Cook, E. T., & Quamma, J. P. (1995). Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children: The effects of the paths curriculum. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 117–136. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006374

Greenberg, L. S., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2006). Emotion in psychotherapy: A practice-friendly research review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 611–630. doi:10.1002/jclp.20252

Greenberg, L. S., & Safran, J. D. (1989). Emotion in psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 44(1), 19–29. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.1.19

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291. doi:10.1017/S0048577201393198

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (2), 348–362. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Gross, J. J., & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3–24). New York: Guilford Press.

Halberstadt, A. G., Denham, S. A., & Dunsmore, J. C. (2001). Affective social competence. Social Development, 10(1), 79–119. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00150

Havighurst, S. S., Duncombe, M. E., Frankling, E. J., Holland, K. A., Kehoe, C. E., & Stargatt, R. (2015a). An emotion-focused early intervention for children with emerging conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(4), 749–760. doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9944-z

Havighurst, S. S., & Harley, A. (2007). Tuning in to kids: Emotionally intelligent parenting program manual. Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

Havighurst, S. S., Kehoe, C. E., & Harley, A. E. (2015b). Tuning in to teens: Improving parental responses to anger and reducing youth externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 148–158. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.005

Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., Kehoe, C. E., Efron, D., & Prior, M. R. (2013). “Tuning in to Kids”: Reducing young children’s behavior problems using an emotion coaching parenting program. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 44(2), 247–264. doi:10.1007/s10578-012-0322-1

Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., Prior, M. R., & Kehoe, C. E. (2010). Tuning in to Kids: Improving emotion socialization practices in parents of preschool children—Findings from a community trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(12), 1342–1350. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02303.x

Hawton, K., Salkovskis, P. M., Kirk, J., & Clark, D. M. (1989). Cognitive behaviour therapy for psychiatric problems: A practical guide. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Hill, C. L. M., & Updegraff, J. A. (2012). Mindfulness and its relationship to emotional regulation. Emotion, 12(1), 81–90. doi:10.1037/a0026355

Hughes, E. K., & Gullone, E. (2008). Internalizing symptoms and disorders in families of adolescents: A review of family systems literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 92–117. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.002

Hughes, E. K., & Gullone, E. (2010). Parent emotion socialisation practices and their associations with personality and emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(7), 694–699. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.042

Jackson, M. C., & Arlegui-Prieto, M. (2016). Variation in normal mood state influences sensitivity to dynamic changes in emotional expression. Emotion, 16(2), 145–149. doi:10.1037/emo0000126

Katz, L. F., & Gottman, J. M. (1991). ‘Marital discord and child outcomes: A social psychophysiological approach’. In Garber, J. & Dodge, K.A. (eds.) The Development of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation:. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (pp. 129–156). doi:10.1017/CBO9780511663963.008

Katz, L. F., Maliken, A. C., & Stettler, N. M. (2012). Parental meta-emotion philosophy: A review of research and theoretical framework. Child Development Perspectives, 6(4), 417–422. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00244.x

Kehoe, C. E. (2014). Tuning in to Teens: Examining the efficacy of an emotion-focused parenting intervention in reducing pre-adolescents’ internalising difficulties. (Doctor of Philosophy Unpublished thesis), The University of Melbourne, Melbourne. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11343/43025

Kehoe, C. E., Havighurst, S. S., & Harley, A. E. (2014a). Examining the efficacy of an emotion-focused parenting intervention in reducing pre-adolescents’ internalising and externalising problems. In Paper presented at the 28th International Congress of Applied Psychology Paris.

Kehoe, C. E., Havighurst, S. S., & Harley, A. E. (2014b). Tuning in to Teens: Improving parent emotion socialization to reduce youth internalizing difficulties. Social Development, 23(2), 413–431. doi:10.1111/sode.12060

Kehoe, C. E., Havighurst, S. S., & Harley, A. E. (2015). Somatic complaints in early adolescence: The role of parents’ emotion socialization. Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(7), 966–989. doi:10.1177/0272431614547052

Kendall, P. C., Gosch, E., Hudson, J. L., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Suveg, C. (2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (2), 282–297. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282

Kim, H. K., Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., Kerr, D. C. R., & Owen, L. D. (2009). Intergenerational transmission of internalising and externalising behaviours across three generations: Gender-specific pathways. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 19(2), 125–141. doi:10.1002/cbm.708

Lane, R. D., Ryan, L., Nadel, L., & Greenberg, L. (2015). Memory reconsolidation, emotional arousal, and the process of change in psychotherapy: New insights from brain science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38. doi:10.1017/S0140525X14000041

Laurent, H. K. (2014). Clarifying the contours of emotion regulation: Insights from parent- child stress research. Child Development Perspectives, 8(1), 30–35. doi:10.1111/cdep.12058

Lauw, M. S. M., Havighurst, S. S., Wilson, K. R., Harley, A. E., & Northam, E. A. (2014). Improving parenting of toddlers’ emotions using an emotion coaching parenting program: A pilot study of tuning into toddlers. Journal of Community Psychology, 42(2), 169–175. doi:10.1002/jcop.21602

Leerkes, E. M., & Crockenberg, S. C. (2006). Antecedents of mothers’ emotional and cognitive responses to infant distress: The role of family, mother, and infant characteristics. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27(4), 405–428. doi:10.1002/imhj.20099

Lenze, S. N., Pautsch, J., & Luby, J. (2011). Parent-child interaction therapy emotion development: A novel treatment for depression in preschool children. Depression and Anxiety, 28(2), 153–159. doi:10.1002/da.20770

Linehan, M. M., Bohus, M., & Thomas, R. L. (Eds.). (2007). Dialectical behavior therapy for pervasive emotion dysregulation: Theoretical and practical underpinnings. NY: Guilford Press.

Lorber, M. F., Mitnick, D. M., & Slep, A. M. S. (2015). Parents’ experience of flooding in discipline encounters: Associations with discipline and interplay with related factors. Journal of Family Psychology. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/fam0000176

Lorber, M. F., & O’Leary, S. G. (2005). Mediated paths to overactive discipline: mothers’ experienced emotion, appraisals, and physiological responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 972–982. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.972

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behavior Research Therapy, 33, 335–343. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Luby, J., Lenze, S., & Tillman, R. (2012). A novel early intervention for preschool depression: Findings from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 53(3), 313–322. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02483.x

Lynch, T. R., Robins, C. J., Morse, J. Q., & Krause, E. D. (2001). A mediational model relating affect intensity, emotion inhibition, and psychological distress. Behavior Therapy, 32(3), 519–536. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80034-4

Maliken, A. C., & Katz, L. F. (2013). Exploring the impact of parental psychopathology and emotion regulation on evidence-based parenting interventions: A transdiagnostic approach to improving treatment effectiveness. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 16(2), 173–186. doi:10.1007/s10567-013-0132-4

Mazursky-Horowitz, H., Felton, J. W., MacPherson, L., Ehrlich, K. B., Cassidy, J., Lejuez, C. W., et al. (2015). Maternal emotion regulation mediates the association between adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and parenting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43, 121–131. doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9894-5

Mence, M., Hawes, D. J., Wedgwood, L., Morgan, S., Barnett, B., Kohlhoff, J., & Hunt, C. (2014). Emotional flooding and hostile discipline in the families of toddlers with disruptive behavior problems. Journal Of Family Psychology: JFP: Journal Of The Division Of Family Psychology Of The American Psychological Association (Division 43), 28(1), 12–21. doi:10.1037/a0035352

Meyer, S., Raikes, H. A., Virmani, E. A., Waters, S., & Thompson, R. A. (2014). Parent emotion representations and the socialization of emotion regulation in the family. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38(2), 164–173. doi:10.1177/0165025413519014

Moretti, M. M., & Obsuth, I. (2009). Effectiveness of an attachment-focused manualized intervention for parents of teens at risk for aggressive behaviour: The connect program. Journal of Adolescence, 32(6), 1347–1357. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.013

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Morris, M. D. S., Steinberg, L., Aucoin, K. J., & Keyes, A. W. (2011). The influence of mother–child emotion regulation strategies on children’s expression of anger and sadness. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 213–225. doi:10.1037/a0021021

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361–388. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x

Myers, S. B., Sweeney, A. C., Popick, V., Wesley, K., Bordfeld, A., & Fingerhut, R. (2012). Self-care practices and perceived stress levels among psychology graduate students. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 6(1), 55–66. doi:10.1037/a0026534

Perlman, S. B., Camras, L. A., & Pelphrey, K. A. (2008). Physiology and functioning: Parents’ vagal tone, emotion socialization, and children’s emotion knowledge. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 100(4), 308–315. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2008.03.007

Platt, R., Williams, S., Ginsburg, G., Williams, S. R., & Ginsburg, G. S. (2016). Stressful life events and child anxiety: Examining parent and child mediators. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47(1), 23–34. doi:10.1007/s10578-015-0540-4

Psychogiou, L., & Parry, E. (2014). Why do depressed individuals have difficulties in their parenting role? Psychological Medicine, 44(7), 1345–1347. doi:10.1017/S0033291713001931

Quick, J. C., Wright, T. A., Adkins, J. A., Nelson, D. L., & Quick, J. D. (2013). Preventive stress management: Principles, theory, and practice Preventive stress management in organizations(2nd ed.). (pp. 103–113). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Ralph, A., & Sanders, M. R. (2006). The ‘teen Triple P’ positive parenting program: A preliminary evaluation. Youth Studies Australia, 25(2), 41–48.

Raver, C. C., & Spagnola, M. (2002). ”When my mommy was angry, I was speechless”: Children’s preceptions of maternal emotional expressiveness within the context of economic hardship. Marriage and Family Review, 34, 63–88. doi:10.1300/J002v34n01_04

Rutherford, H. J. V., Wallace, N. S., Laurent, H. K., & Mayes, L. C. (2015). Emotion regulation in parenthood. Developmental Review, 36, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2014.12.008

Saarni, C. (1999). The development of emotional competence. New York: Guilford Press.

Salmon, P. (2001). Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: A unifying theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 33–61. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00032-X

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the trait meta-mood scale. In J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion disclosure and health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sanders, M. R., & Markie-Dadds, C. (1996). Triple P: A multilevel family intervention program for children with disruptive behaviour disorders. In T. Cotton & H. Jackson (Eds.), Early intervention and prevention in mental health (pp. 59–85). Melbourne, Australia: Australian Psychological Society.

Sanders, M. R., Markie-Dadds, C., Tully, L. A., & Bor, W. (2000). The Triple P-positive parenting program: A comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 624–640. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.624

Schore, J. R., & Schore, A. N. (2008). Modern attachment theory: The central role of affect regulation in development and treatment. Clinical Social Work Journal, 36(1), 9–20. doi:10.1007/s10615-007-0111-7

Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Bobik, C., Coston, T. D., Greeson, C., Jedlicka, C., … & Wendorf, G. (2001). Emotional intelligence and interpersonal relations. The Journal of Social Psychology, 141(4), 523–536. doi:10.1080/00224540109600569

Scott, S., & Dadds, M. R. (2009). Practitioner review: When parent training doesn’t work: theory-driven clinical strategies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 50(12), 1441–1450. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02161.x

Sheeber, L. B., Kuppens, P., Shortt, J. W., Katz, L. F., Davis, B., & Allen, N. B. (2011). Depression is associated with the escalation of adolescents’ dysphoric behavior during interactions with parents. Emotion, 12(5), 913–918. doi:10.1037/a0025784

Shenk, C. E., & Fruzzetti, A. E. (2011). The impact of validating and invalidating responses on emotional reactivity. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(2), 163–183. doi:10.1521/jscp.2011.30.2.163

Shipman, K. L., Schneider, R., Fitzgerald, M. M., Sims, C., Swisher, L., & Edwards, A. (2007). Maternal emotion socialization in maltreating and non-maltreating families: Implications for children’s emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 268–285. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00384.x

Shortt, J. W., Eddy, J. M., Sheeber, L., & Davis, B. (2014). Project home: A pilot evaluation of an emotion-focused intervention for mothers reuniting with children after prison. Psychological Services, 11(1), 1–9. doi:10.1037/a0034323

Stettler, N., & Katz, L. F. (2014). Changes in parents’ meta-emotion philosophy from preschool to early adolescence. Parenting: Science and Practice, 14(3/4), 162–174. doi:10.1080/15295192.2014.945584

Stocker, C. M., Richmond, M. K., Rhoades, G. K., & Kiang, L. (2007). Family emotional processes and adolescents’ adjustment. Social Development, 16(2), 310–325. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00386.x

Suchy, Y. (2011). Clinical neuropsychology of emotion. New York, US: The Guilford Press.

Suveg, C., Sood, E., Barmish, A., Tiwari, S., Hudson, J. L., & Kendall, P. C. (2008). ”I’d rather not talk about it”: Emotion parenting in families of children with an anxiety disorder. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 875–884. doi:10.1037/a0012861

Taylor, T. K., & Biglan, A. (1998). Behavioral family interventions for improving child-rearing: A review of the literature for clinicians and policy makers. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1(1), 41–60. doi:10.1023/A:1021848315541

Webb, T. L., Miles, E., & Sheeran, P. (2012). Dealing with feeling: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 138(4), 775–808. doi:10.1037/a0027600

Webster-Stratton, C., & Hammond, M. (1990). Predictors of treatment outcome in parent training for families with conduct problem children. Behavior Therapy, 21, 319–337. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80334-X

Webster-Stratton, C., & Reid, M. J. (2007). Incredible years parents and teachers training series: A head start partnership to promote social competence and prevent conduct problems. In P. Tolan, J. Szapocznik, & S. Sambrano (Eds.), Preventing youth substance abuse: Science-based programs for children and adolescents. (pp. 67–88): American Psychological Association.

Weersing, V. R., Rozenman, M. S., Maher-Bridge, M., & Campo, J. V. (2012). Anxiety, depression, and somatic distress: Developing a transdiagnostic internalizing toolbox for pediatric practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(1), 68–82. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.06.002