Abstract

The principal aim of this chapter is to review the contribution that psychosocial research has made to an understanding of marijuana use by young people in the late seventies. A time of increasing acceptance in societal attitudes about its use. After a review of the epidemiology of marijuana use, research documenting the influence of the social environment, of personality, and of other behaviors on marijuana use is considered. Finally, research on the role of marijuana in psychosocial development is explored. The chapter concludes with consideration of decriminalization of marijuana use, and regulation of its use as is done with alcohol, a legal drug.

Reprinted with permission from:

Jessor, R. (1979). Marihuana: A review of recent psychosocial research. In R. L. DuPont, A. Goldstein & J. O’Donnell (Eds.), Handbook on drug abuse (pp. 337–355). Washington, DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Marijuana use

- Psychosocial research on marijuana

- Epidemiology of marijuana use

- Marijuana and the social environment

- Marijuana and personality

- Marijuana and other behavior

- Marijuana and psychosocial development

- Co-variation of problem behaviors

- Marijuana decriminalization

Introduction

It was not much more than a decade or so ago that marijuana use in the United States was confined to the inner city ghetto, to blacks, or to jazz musicians. Within the span of a relatively few years, usage has become widespread and, perhaps more important for the future, public attitudes toward marijuana have become more accepting. Even the legal institutions have demonstrated an increasing tolerance through statutory accommodation in 10 States and a relaxation of the enforcement of existing statutes in other locales. As much as 5 years ago, some observers were already interpreting these trends as irreversible: “… one thing is unmistakably clear: marijuana use is now a fact of American life” (Brotman & Suffet, 1973, p. 1106); “… marijuana use will probably become a cultural norm within a few years for persons under 30” (Hochman & Brill, 1973, p. 609). How quickly such change may actually have occurred is indicated by Akers’ (1977) recent description of the American scene, a description that would have elicited sharp disbelief even as recently as the late 1960s: “Marijuana is smoked in an offhand, casual way … Before, during, or after sports events, dates, public gatherings, parties, music festivals, class or work will do; there is no special place, time, or occasion for marijuana smoking. The acceptable places and occasions are as varied as those for drinking alcohol” (p. 112).

Such a description does not apply, of course, to all segments of the American population or to all parts of the country. But it suggests that what we have been witnessing with regard to marijuana use may well be a rather unusual instance of cultural change, noteworthy for its rapidity and for its parallel with other changes, for example in sexual attitudes and behavior , that have been underway simultaneously. Whether the change will be an enduring one and whether the use of marijuana will, as with alcohol, become fully institutionalized in American society is still a matter of considerable speculation and debate. But there is little in the research evidence currently available to suggest that it will not.

An unusual aspect of the recent American experience with marijuana is that, almost constantly from its inception, it has been under research scrutiny. While surveys have played perhaps the central role in monitoring the scope and contour of marijuana use, and in establishing the pattern of factors associated with that use, an enormous range of studies of all kinds has accumulated. Various aspects of the literature have already been appraised in the reports of the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse (1972a, b, 1973a, b) and in those of the Canadian Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs (1972, 1973). Excellent reviews of the research on drug use and abuse, each devoting considerable attention to marijuana, have appeared in more recent years (Braucht et al., 1973; McGlothlin, 1975; Sadava, 1975; Gorsuch & Butler, 1976; Petersen, 1977; Kandel, 1978a). Our aim in this review is to touch briefly on some of the main findings of the most recent research, that published within the preceding 5-year period. Our focus will be selective and illustrative rather than exhaustive, and it will be confined primarily to the psychosocial research domain.

The last 5 years have seen important indications of the coming of age of psychosocial research on marijuana, Despite problems that continue to plague the field, for example, the noncomparability of measures of use across different studies, an overview of the literature since the late 1960s reveals a number of salutary trends. There has been a shift from reliance on easily available, ready-to-hand, but largely adventitious samples to carefully drawn, national probability samples representative of important segments of the population; for example, Abelson et al. (1977) for youth and adults in households, Johnston et al. (1977) for seniors in high school, and O’Donnell et al. (1976) for young men between 20 and 30. The first two of these surveys are in place as annual monitoring efforts that enable the estimation of population parameters and the tracking of change in the incidence and prevalence of marijuana use on a national level. There has also been a trend toward a more textured and differentiated assessment of marijuana use behavior; instead of the earlier focus on whether or not there has ever been any use at all of marijuana, more recent studies have shown concern for a variety of dimensions of use including frequency, recency, amount per occasion, and the simultaneous use of other drugs.

Increasingly, the research has tended to encompass measures of a larger network of psychosocial explanatory variables in contrast to the earlier preoccupation with demography and with epidemiological mapping. Along with this trend toward enlargement of the measurement framework, there has been more attention paid to distal variables —variables that are less obvious or that are linked to marijuana use by theory—and a less exclusive interest in proximal variables, those that are more obviously connected with marijuana use, such as positive attitudes toward drug use or the prevalence of drug use among one’s friends. Another trend that has become apparent is the inclusion of measures of behavior other than marijuana use in studies of the latter. This trend goes beyond an interest in assessing other kinds of drug-using behavior, or investigating the possible effects that marijuana may have on other behaviors, such as academic performance, or crime and delinquency . Rather, it has been an attempt to understand marijuana use as part of a larger pattern of behavioral adaptation to life situations and to explore its commonalities with other forms of socially structured action.

Two other trends apparent in the marijuana research literature of recent years need mention. One of these has been the remarkable increase in studies that extend over time and that rely upon panel or longitudinal or developmental design (Johnston, 1973; Kandel, 1975; Sadava, 1973a; Smith & Fogg, 1978; Mellinger et al., 1976; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Johnston et al., 1978a, 1978b). An entire volume is devoted exclusively to longitudinal studies of drug use and includes contributions from a number of the major recent investigations (Kandel, 1978b). The enlargement in explanatory capability that is achieved by longitudinal design, including the possibility of establishing temporal order and sequence, makes this trend one of exceptional significance.

The final direction that is obvious to even a casual observer of recent developments in psychosocial research on marijuana is the shift toward more complex and sophisticated research procedures. This trend includes more careful selection of research participants with appropriately matched control groups , such as was done in the elegant and already classic study of Vietnam veterans by Lee Robins (1974); the reliance on independent sources of information as in Kandel’s (1974a) use of participant-parent-friend triads, and in Smith and Fogg’s (1978) employment of peer ratings; the use of cohort-sequential design to permit the appearance of cohort effects in longitudinal studies (Jessor & Jessor, 1977); and the employment of multivariate analytic procedures such as multiple regression and path analysis to deal with complex networks of variables. The empirical sophistication of the more recent studies is attested to by the fact that many of them report that very substantial portions of the variance in marijuana, use—50 percent is not unusual—can be accounted for by multivariate analyses of their data.

These observations, while heartening, are not meant to convey an unrealistic sense of either knowledge or accomplishment in psychosocial research on marijuana. Refractory problems abound, and explaining 50 percent of the variance in marijuana behavior means, after all, that fully 50 percent remains unexplained. The point to be made is that these various trends, insofar as they come to characterize the ongoing research enterprise as a whole, hold promise for greater understanding in the future.

Commentary on the research of the past 5 years is organized under six different headings. The first section deals briefly with the current epidemiology of marijuana use, its extent and its distribution, and the direction of change in prevalence that has characterized the recent past. The second, third, and fourth sections focus respectively on social environmental, personality, and behavioral factors associated with marijuana use; these three areas constitute the main component systems in the psychosocial domain. The fifth section deals with developmental research on marijuana use. The final section considers some implications of the current findings for further research and for a possible initiative in the direction of the prevention of marijuana abuse.

Epidemiology of Marijuana Use

Nationwide surveys of the general population, or of targeted subgroups within it, have yielded an unusual amount of information about the prevalence and distribution of marijuana use in this country. Josephson (1974) has summarized the findings from some of the earlier surveys, especially those bearing on the adolescent age group, and McGlothlin (1977) has recently reviewed the major epidemiological studies through 1976. From the perspective of early 1978, it is clear that marijuana is the most widely used of the illicit drugs, that a substantial proportion of the population—within certain age groups, it is a sizable majority—has had some experience with marijuana, and that marijuana use is continuing to increase in prevalence and in intensity, despite earlier forecasts that a leveling off was to be expected (see, for example, National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse [1973a, p. 78]).

The most important sources of recent epidemiological information are the annual household surveys of the general population aged 12 and older sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and carried out by the Response Analysis Corporation of Princeton, New Jersey and the Social Research Group of George Washington University (see Abelson & Atkinson, 1975; Abelson & Fishburne, 1976; and Abelson et al., 1977 for the most recent in the series); the national surveys of high school seniors beginning with the class of 1975 and including the classes of 1976 and 1977 carried out by the Monitoring the Future project at the University of Michigan (Johnston et al., 1977); and the nationwide survey of young men, aged 20 to 30 in 1974, drawn from the Selective Service registrations to be representative of young men in the continental United States (O’Donnell et al., 1976). Other studies of epidemiological interest are the longitudinal surveys of a national sample of high school males in the class of 1969—the Youth in Transition project—followed up most recently in 1974 (Johnston, 1973, 1975), and the annual surveys of junior and senior high school students in San Mateo County, California, a local area of interest because of comparatively high rates of drug use and the availability of a decade of repeated surveys (Blackford, 1977).

In the most recent national survey of the general population (Abelson et al., 1977), lifetime prevalence (whether marijuana has ever been used, even once) is substantial among older adolescents and young adults, and markedly patterned by age:

Age | Percent Ever Used |

|---|---|

12–13 | 8 |

14–15 | 29 |

16–17 | 47 |

18–21 | 59 |

22–25 | 62 |

26–34 | 44 |

35+ | 7 |

Six out of 10 in the age range from 18 to 25 have had some experience with marijuana by 1977, and that figure holds fairly well for both males (66 percent) and females (55 percent). While the lifetime prevalence rate falls off on both sides of this time period, nearly half of those who are 16 to 17 years old and nearly half of those who are 26 to 34 years old have used marijuana at least once. Such data make clear the pervasiveness with which this illicit behavior has occurred, at some time, in a large segment of the American population . However, it should be emphasized that most of those who have had experience with marijuana have had only limited experience, and for many of them that experience is not current. For example, in contrast to the 60 percent of young adults aged 18 to 25 who have ever used marijuana, only about 28 percent of that age group used it in the month prior to the survey.

Beyond age, prevalence of marijuana use, both lifetime and current, shows variation in relation to sex (males higher than females), to census region (Northeast and West higher, South lower), to population density (large metropolitan areas higher), to education (college higher), and, in the younger age range, race (white higher). This variation does not hold across all age categories, and it is not comparable in salience to that associated with age per se.

Perhaps of most significance is the contribution of the 1977 survey to an understanding of whether prevalence has now stabilized or continues the increasing trend of the past decade. In comparison with the findings of the 1976 survey, the most recent one does reveal a significant increase for the 12- to 17-year age group in both lifetime prevalence and current use, and for the 18- to 25-year and the 26- to 34-year age groups in lifetime prevalence. Even where the changes over the year interval were not significant, the overall pattern for most breakdowns was one of increases and, when viewed against the results of the entire series of earlier surveys beginning in 1971, the trend toward increased prevalence of marijuana use is clearly continuing and is engaging broader segments of the population.

In the O’Donnell et al. (1976) nationwide survey of young men 20 to 30 interviewed in 1974–75, the age-relatedness of prevalence of marijuana use was also very apparent. While overall lifetime prevalence was 55 percent, the percentages for the younger age groups were in the 60s, whereas those for the older age groups were in the 40s; age 24 yielded the highest rate—66 percent with some experience with marijuana.

With respect to the sample of more than 17,000 high school seniors in the class of 1977, the findings of the latest survey from the Monitoring the Future project (Johnston et al., 1977) are illuminating. Lifetime prevalence in the sample, has reached 56 percent, a majority of this 18-year-old, in-school group having had at least one experience with marijuana by 1977. Current prevalence (use in the past month) has reached 35 percent in this sample, involving 1 of every 3 high school seniors. Of special interest in the findings is the fact that 9.1 percent of the survey sample, 1 out of 11, report daily or nearly daily use of marijuana, a rate that is now higher than that reported for the daily use of alcohol (the latter was 6.1 percent in the class of 1977). Lifetime prevalence of marijuana use is higher among males (62 percent) than females (51 percent), especially when higher frequency of use is considered, among the noncollege bound (60 percent) than the college bound (52 percent), highest in the Northeast (63 percent) and lowest in the South (51 percent), and highest in the very large cities (63 percent).

Buttressing the magnitude of these figures is the evidence that prevalence in the class of 1977, both lifetime and current, has significantly increased over that for the class of 1976 and, in turn, that of 1975, and the increases tend to characterize all of the subgroups previously listed. As in the 1977 national household survey discussed earlier, these data also indicate a continuation of the trend toward increasing prevalence of use for the specific age group represented by the high school senior sample.

Another indication of an increase in prevalence comes from the San Mateo survey (Blackford, 1977). The 1977 data are reported for annual prevalence (use in the preceding year); that rate was 64.5 percent for 12th grade males (up from 61.1 percent in 1976) and 61.4 percent for 12th grade females (up from 56 percent in 1976). (For purposes of comparison, annual prevalence in the 1977 Monitoring the Future survey was 53 percent for the 12th grade males and 42 percent for 12th grade females.) The San Mateo increases over the past year are of particular significance since many expected that this high rate area had already reached saturation and was stabilizing at a level that might be a ceiling for marijuana prevalence.

Finally, the 1974 follow-up of the class of 1969 cohort in the Youth in Transition study shows quite clearly that the lifetime prevalence levels reached in high school do continue to increase with increasing age of the cohort after high school (Johnston, 1975). Lifetime prevalence for the class of 1969 was 20 percent in their senior year, rose to 35 percent by a year later, and reached 62 percent by the 1974 follow-up when the cohort was 23 years old. Thus, there is no evidence for a prevalence plateau after graduation from high school.

The perspective that emerges from this series of nationwide surveys is that some experience with marijuana has, by 1977, become statistically normative among older adolescents and young adults, and that about a third of those in this age range have used marijuana in the past month. Lifetime prevalence is increasing in the next older age group as the younger cohorts age into it (the rate for those aged 26 to 34 more than doubled from 1972, when it was 20 percent, to 1977, when it was 44 percent; see Abelson et al. [1977]); the trend toward higher prevalence has continued to generate significant annual increases in all of the most recent surveys; initiation into marijuana use is taking place earlier (Johnston et al., 1977); and daily use—a measure reflecting more than fortuitous involvement with marijuana—has increased in recent years. The continuing increase in marijuana use, incidentally, appears not to be specific to the United States; according to Smart (1977), its use is still increasing in Canada as well (see also Smart & Fejer, 1975).

The implications of these epidemiological developments are significantly sharpened by two other considerations. First, important changes have simultaneously been occurring in many of the factors that are immediately relevant to the likelihood of marijuana use, factors such as knowing someone who has used marijuana, having the opportunity to use marijuana, beliefs about the harmfulness and risk associated with marijuana use, and attitudes about whether marijuana use should be legalized or decriminalized. According to the findings from both the 1977 national survey (reported in Miller et al., 1978) and the 1977 Monitoring the Future survey (Johnston et al., 1977), all of these factors have changed over recent years in the direction of greater exposure to and availability of marijuana, less perceived risk of use, less disapproval for use, and less support for legal prohibition of use. More recently, the annual American Council on Education survey of 300,000 entering freshmen to colleges and universities in the United States in the fall of 1977 found, for the first time, that a majority (53 percent) of freshmen supported legalization of marijuana (Astin et al., 1978). These convergent changes in what has been called “the social climate ” of marijuana use (Miller et al., 1978) strongly suggest that involvement with marijuana is likely to continue to increase in the future.

The second consideration has to do with the recognition that national survey findings, despite the exceptional quality of those reviewed here, have certain limitations. Household surveys do not capture those not living in households, and school surveys do not capture dropouts; in both cases, the groups that are missed probably have higher rates of marijuana use than those who are included, and the survey findings are, to some degree, likely to be underestimates of population prevalence. Perhaps of more significance, nationwide surveys may not adequately reflect the fact that particular social or geographic locations may be of more than average influence on cultural change; thus, locations where marijuana use may be very high—for example, in a liberal arts college in a large metropolitan university—or where its use is an accepted part of “the scene”—for example, the Bay Area—may have more impact on future trends in the acculturation of our society to marijuana than is apparent when those locations are averaged in with other sampling units.

The data that have emerged from the latest epidemiological surveys, taken together with the trends that are evident across the recent series of such surveys, suggest that marijuana has to some extent become embedded in American culture (see also Ray, 1978). Its institutionalization appears to be reflected not only in the broad pattern of its availability and use, but also in the supportive social definitions that are increasingly shared about its nature and its function. If, indeed, this has become the case, then it would seem apposite for national concern about marijuana to shift from the question of its use to the problem of its abuse.

Marijuana Use and the Social Environment

As we have already noted in the preceding section, variation in marijuana use is less sharply patterned than it was in the past by attributes of the sociodemographic environment ; where such attributes still emerge as significantly related, the trends over time suggest that their role is a diminishing one. This is true for urbanicity or population density (Johnston et al., 1977) and for race and socioeconomic status (Miller et al., 1978). It is also true for sex; although national rates remain higher for males than females, the difference is not of the magnitude that might have been expected for such an illicit behavior, and, in several recent studies, the sex difference in lifetime prevalence has all but disappeared (Wechsler & McFadden, 1976; Akers et al., 1977; Jessor & Jessor, 1977). The decline in distinctiveness of population density or urban residence as relevant environmental attributes is paralleled by a declining distinctiveness of other characteristically use-prone settings such as college campuses or military life. O’Donnell et al. (1976), for example, describe the effects of military service on drug use as “invisible” in their cohorts of men between 20 and 30, and this applies to effects on marijuana use as well. At the level of the demographic environment, then, there has been a trend toward homogenization as far as variation in marijuana use is concerned. Put in other terms, demographic environmental attributes account for only a small, and increasingly a smaller, portion of the variance in marijuana use.

By contrast, the environmental factors that have emerged repeatedly as salient in relation to the prevalence and intensity of marijuana use are those that refer to the environment of social interaction. The key role played by friendship patterns and interpersonal relations in providing access to and availability of marijuana, models for using it, and social support for such use have been affirmed in a host of studies. One investigator has concluded that, in explaining adolescent marijuana use, “marijuana use by one’s friend … may be the critical variable” (Kandel, 1974b, p. 208). This emphasis on friends or peers as the most important social agent, and on their actual use of marijuana as the most important contextual variable, while supported by the research, ought not to result in ignoring other agents or other aspects of the social interaction situation. The most general point to be made from the research is that marijuana use varies directly with attributes of the context of social interaction—with social models, with social reinforcements, and with social controls, both general and marijuana-specific.

The importance of the use of marijuana by one’s friends is readily seen in the data from the national survey of young men 20–30 (O’Donnell et al. 1976). Among users of marijuana in the survey year (1974–75), fully 98 percent report that at least “a few” of their friends are current users; among never users of marijuana, the comparable figure is only 56 percent. Not only is own use versus nonuse related to use by friends, but intensity of own use varies directly with prevalence of use among one’s friends. Again referring to the O’Donnell et al. (1976) data, the percent who report “more than a few friends now using marijuana” are: non users (18); experimental users (41); light users (69); moderate users (76); and heavy users (94). The heavier the involvement with marijuana, the more likely that one is embedded in a friendship network in which marijuana use is a characteristic pattern of behavior; see also Johnson (1973).

Although the earlier interpretations of the importance of friends or peers used the evidence to sustain the notion of a drug subculture with its own values and norms (Suchman, 1968), or of a student subculture (Thomas et al., 1975), the tenability of such a perspective is increasingly eroded by the spread of marijuana use to broader and broader segments of the population. Under such circumstances, there seems little need for recourse to a subculture concept; indeed, the role that peers play in relation to marijuana use appears to be no different than the role they play in relation to various other domains—values, sexual behavior, styles of dress—in which their socialization impact is considerable. Dispensing with the subculture notion enables the assimilation of peer influence on marijuana use into the larger function of peer socialization as a whole; (for an empirical questioning of the notion of a drug subculture among adolescents, see Huba et al. [1978]).

In an interesting study of peer influence on marijuana use among a representative sample of public secondary students in New York State, Kandel (1973, 1974a, b) collected independent data from the best school friend and from the parents of a subsample of her respondents. Peer drug use emerged as a far more important influence on the respondent’s use of marijuana than parental use of drugs. With the availability of independent data from parents and friends, Kandel was able to compare the relation of perceived parental drug use with parent-reported drug use, and the relation of perceived peer drug use with peer-reported drug use. In both cases, the relation to the respondent’s own use was attenuated when independent data rather than perceived data were used. This is an important finding since most studies rely upon perceived data. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the nature of the relationships is maintained even though attenuated, and it should also be noted that the question of the differential validity of the two kinds of data is not resolved in the study.

More recently, the Jessors have explored the influence of environmental factors on variation in marijuana use in their longitudinal study of high school and college youth (Jessor & Jessor, 1973, 1977, 1978). Consonant with the earlier discussion, they found almost no relation between attributes of the sociodemographic environment, including the Hollingshead index of socioeconomic status, and marijuana use. Employing, instead, the concept of the “perceived environment” (Jessor & Jessor, 1973), they distinguish variables that are conceptually proximal to marijuana use (such as models and approval for its use which directly implicate its occurrence), and variables that are conceptually distal to marijuana use (such as general peer support, or parental controls, or relative parent-versus-peer influence which can have only indirect implications for marijuana use). The usefulness of the proximal-distal distinction is that it calls attention to less immediately obvious aspects of the social environment than whether or not one’s friends use marijuana, and it yields, thereby, a more textured analysis of environmental influence. As expected, proximal variables such as friends’ models for marijuana use were consistently the most powerful, yielding correlations in the .60s with marijuana involvement; distal variables such as the exercise of interpersonal controls by friends were considerably less powerful, yielding correlations in the .30s, but still highly significant. Taken together as a system, the perceived environmental variables accounted for about 40 percent of the variance in involvement with marijuana in both the high school and college studies (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). These findings about the salient role of the environment are fully replicated in a nationwide survey of 13,000 secondary school youth (Chase & Jessor, 1977).

The role of friends in providing direct social reinforcement or punishment for marijuana use, knowledge about and normative definitions of use, as well as models for use, was investigated in a recent effort to test another version of social learning theory (Akers et al., 1977). Carried out under the aegis of the Boys Town Center in Nebraska, it involved about 3,000 secondary students in 8 Midwestern communities. Again, differential association with using or nonusing friends was found to be the most powerful variable, but the study offers a more differentiated analysis of the variables through which the influence of friends is exerted. Despite its demonstrably lesser influence, the role of parents may not be entirely dismissed when marijuana use among adolescents and youth is considered. Already noted has been Kandel’s (1974b) finding about the influence of parental use of psychoactive drugs on the adolescent’s use of marijuana. Other aspects of parental influence, beyond whether they themselves use drugs, have also been investigated. Variation in marijuana use has been linked to the degree of parental strictness and controls , to parental affection and support, and to parental conventionality or traditionality in ideological outlook—the greater each of these parental attributes, the less the marijuana involvement by the adolescent (Jessor & Jessor, 1974; Brook et al., 1978; Prendergast, 1974), Of interest is the evidence that the role of parental support and controls—at least as perceived—diminishes in its importance for marijuana use from the younger aged, high school period to the older aged period when youth are in college (Jessor & Jessor, 1977).

The restriction of this section to peer and parent influence in the environment of social interaction reflects the almost exclusive concern of researchers with just these two agents of socialization, support, and control. Almost no attention has been paid to the church or school as institutions of socialization, or to symbolic agents such as the television media. What little research there is, however, suggests that involvement with all three of these latter sources of influence may serve to control against involvement with marijuana use; (see Jessor & Jessor, 1977, chapter 11).

The prepotent role of the social interaction context —the prevalence of models among one’s friends, of attitudes of approval or at least lack of disapproval, and of access to the drug and to the opportunity to use it—is empirically well established by the research of recent years. But the significance of this generalization should be tempered on at least two grounds. First, every study showing the importance of friends’ usage of marijuana showed, nevertheless, that some proportion of those with friends or acquaintances who are users themselves do not use. How does one account for this? The fact that not everyone behaves the same way in the same context of interaction raises the need for other kinds of explanatory factors, factors that refer to individual differences, differences not in social context variables but in personality. Second, all of the trend data suggest that the future will bring higher base rates of use and of knowledge of users. At some point soon, there is likely to be a homogenization of the social interaction environment as far as marijuana use is concerned; that is, most people will have at least some friends who use, will know other people who use, and will perceive little social disapproval for use. Yet it is quite predictable that even in such a homogeneously use-prone environment, some proportion of people will nevertheless refrain from use (at least that is the lesson from alcohol). To account for those who refrain will require, again, recourse to factors that are not those of the shared social environment but those that reflect individual differences in personality. Research on the latter is the concern of the following section.

Marijuana Use and Personality

Recent research has established coherent and systematic linkages between aspects of personality and variation in marijuana use. Despite quite different levels of analysis, theoretical orientations, populations, and measuring instruments, there is a notable degree of consistency in what has been found about the personality correlates of use versus nonuse or of degree of involvement with marijuana. And the pattern of findings tends to be relatively invariant over sex, ethnic status, and other demographic attributes. In the studies that have been reviewed, personality refers to that set of relatively enduring psychological attributes that characterize a person and constitute the dimensions of individual differences, including values, attitudes, needs, beliefs, expectations, moral orientations, and other such essentially sociocognitive variables. Personality in this body of research reflects more the sociocognitive level of analysis than it does the underlying dynamics of the traditional psychoanalytic perspective. Important to emphasize, also, is that these attributes of personality are neutral with respect to the issue of adjustment-maladjustment or the question of psychopathology; the relevance of the latter wilt be addressed subsequently as an empirical issue rather than as one that is necessarily inherent in any general concern with personality. Finally, many of the personality attributes that have been established as correlates of involvement with marijuana have also been shown to be antecedents or precursors of such involvement. This is a finding of central significance in strengthening conviction about the systematic tie between personality and marijuana use behavior.

Perhaps the largest generalization that is warranted by the research on personality is that users of marijuana differ from nonusers on a cluster of attributes reflecting nonconventionality, nontraditionality, or nonconformity . This emphasis was, of course, foreshadowed in the early paper on the “hang-loose ethic” by Suchman (1968). Involvement with marijuana has been associated with a variety of components of such a cluster: with more critical beliefs about the norms and values of the large society and with a sense of disaffection with or alienation from it (Knight et al., 1974; Groves, 1974; Hochman & Brill, 1973; Weckowicz & Janssen, 1973; Jessor et al., 1973); with less religiosity (Rohrbaugh & Jessor, 1975); and with a more tolerant attitude toward deviance, morality, and transgression (O’Donnell et al. 1976; Brook et al., 1977a, b; Jessor & Jessor, 1978). Related to the same cluster are the findings about the greater rebelliousness (Smith & Fogg, 1978), ascendency (Gulas & King, 1976), and value on and expectation for independence or autonomy (Sadava, 1973b; O’Malley, 1975; Jessor et al., 1973) of users or future users in contrast to nonusers. Conventionality-unconventionality is reflected further in the greater emphasis by nonusers on achievement and achievement striving-conventional goals of our society (Holroyd & Kahn, 1974; Sadava, 1973b; Mellinger et al., 1975; Chase & Jessor, 1977; Jessor et al., 1973) and on responsibility (Gulas & King, 1976). Nonusers also score higher on the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale , an index of social conformity (Brook et al., 1977a, b). These findings are consonant across early reports (Hogan et al., 1970) and also more recent studies (Johnston, 1974; Kandel et al., 1978) which emphasize the notions of conformity to adult or societal expectations and conventionality as distinguishing nonusers from users or heavier users.

A second generalization about personality differences associated with variation in marijuana use is that users tend to be more open to experience, more aesthetically oriented, more interested in creativity, play, novelty, or spontaneity (Groves, 1974; Stokes, 1974; Segal, 1975; Naditch, 1975; Weckowicz & Janssen, 1973; Shibuya, 1974; Mellinger et al., 1975; Holroyd & Kahn, 1974). These attributes are not unrelated to the preceding cluster of conventionality, but what is emphasized more is a cognitive style of receptivity to uncertainty and change as against an emphasis on familiarity and inflexibility. Since marijuana is often sought specifically to initiate change in mood or outlook, this linkage with a general interest in sensation- or experience-seeking (Segal, 1975; Kohn & Annis, 1978) is a logical one.

A third generalization, perhaps, is that marijuana use was associated not only with lower value on achievement but with lower expectations of being able to gain achievement satisfaction . These findings make relevant the possibility that marijuana use can be a response to frustration, to the perception of blocked access to valued goals, and to the anticipation of failure; it may be implicated as a way of coping with such feelings or as representing a choice to pursue alternative goals than those for which little success is anticipated (Carman, 1974; Braucht, 1974; Jessor et al., 1973).

Other attributes of personality have also received considerable attention, but the empirical consensus on these remains equivocal (see the excellent compendium edited by Lettieri (1975) for a number of articles dealing with various personality measures). One of these is the internal-external control (I-E) or locus of control variable . Plumb et al. (1975) have published an extensive review of the mixed outcomes of the relevant I-E studies. Some investigators report that marijuana use is associated with higher internal control (Brook et al., 1977a, b; Sadava, 1973b). Other investigators (Jessor & Jessor, 1977) find the I-E variable yields little distinction between high school and college users and nonusers, but where there is a significant relationship—for high school males only—it is in the opposite direction, marijuana involvement being associated with higher externality (for similar results, see also Naditch [1975]). Another attribute that has been studied intensively but also with inconsistent results is self-esteem. Kaplan (1975) has related a lowering of self-esteem to subsequent involvement with marijuana use, and Norem-Hebeisen (1975) reports some cross-sectional discriminability of her self-esteem measures, but others have been unable to link variation in self-esteem to marijuana use or subsequent onset of use (O’Malley, 1975; Kandel et al., 1978; Jessor & Jessor, 1977).

Kandel (1978a) has correctly called attention to the fact that affective and mood states as personality attributes have been given scant attention in approaches focused on the sociocognitive level of analysis of personality. Her own work has suggested depressive mood as a modest predictor of subsequent marijuana use (Paton et al., 1977). With regard to another affect-related attribute—extroversion as measured by the Eysenck Personality Inventory—Wells and Stacey (1976) found it unrelated to drug use among young people in Scotland, and Smart and Fejer (1973) found adult marijuana users scoring in the normal range on extroversion, though higher than nonusers. Another possibly relevant attribute in this domain is field dependence-independence , but it also fails to distinguish in relation to marijuana (Weckowicz & Janssen, 1973).

Although the foregoing summary has sought to integrate the various findings, all of them have emerged from studies that have emphasized differences between users and nonusers in magnitude of an attribute or a set of attributes. An unusually interesting study has asked a different kind of question: Is the organization of personality attributes different between user and nonuser groups? Huba et al. (1977) studied the organization of 15 needs, drawn from Henry Murray’s personality theory , in over 1,000 college students at two universities. They found good factorial stability for the needs, for both sexes, in both drug and nondrug groups, and were able to establish that personality organization is qualitatively the same in users of marijuana or other drugs as in nonusers of these substances. This attention to the organizational structure of personality motivation is especially salutary because it suggests that while users differ quantitatively from nonusers (as they do in this study, also), they are qualitatively similar to nonusers in organization and functioning.

A concern with personality has been central to the work of the Jessors in their longitudinal study of high school and college cohorts. Their personality and marijuana findings have been presented in a recent book (Jessor & Jessor, 1977), and represent an effort to deal with personality as a system of motivations, instigations, beliefs, and personal controls. In relation to a criterion of degree of involvement with marijuana, the personal control variables are shown to be most strongly related; higher involvement is associated with lower religiosity and greater tolerance of deviant behavior among both high school and college males and females. At the high school level, higher involvement with marijuana is also associated with lower value on academic achievement, lower expectations of attaining that goal, and with higher value on independence and on independence relative to achievement. It is significant that none of these latter associations holds at the college level. Finally, the higher the involvement with marijuana, the greater the critical attitude toward the society and its institutions for both sexes in both high school and college. To assess the role of personality as a system, multiple correlations were run against the marijuana use criterion; they show that between 20 and 25 percent of the variance in marijuana involvement can be accounted for by the joint role of the set of personality measures—a substantial and significant amount (although less than that accounted for by the perceived environment system). In an application of the same framework to a national sample of 13,000 high school youth, personality system variables again accounted for about 20 percent of the variance in marijuana involvement for both sexes (Chase & Jessor, 1977).

A recurrent issue when personality is dealt with is whether or not maladjustment or psychopathology is implicated in the use of marijuana. The findings in the foregoing studies are generally neutral with regard to psychopathology, stressing, instead, variation in attitudes, values, beliefs, and other such sociocognitive aspects of personality. But a large number of studies have been specifically concerned with answering the maladjustment-psychopathology question, and the empirical outcome seems quite clear. With only a few exceptions (Wells & Stacey, 1976; Smart & Fejer, 1973), the preponderant conclusion is that there is no association between marijuana use and maladjustment or psychopathology (Naditch, 1975; Mellinger et al., 1975; O’Malley, 1975; Stokes, 1974; Goldstein & Sappington, 1977; Costa, 1977; Hochman & Brill, 1973; Cross & Davis, 1972; Weckowicz & Janssen, 1973; McAree et al., 1972; Richek et al., 1975). In some instances, a very heavy marijuana user group will appear to have more extreme indication of psychopathology (e.g., Cross & Davis, 1972), but such a group is inevitably involved with multiple drug use or with the use of harder drugs in addition to marijuana, and this state of affairs confounds the inference about marijuana use alone. Where only marijuana is involved (but including alcohol and tobacco, of course), the explanation of variation in marijuana use gains nothing from recourse to psychiatric or psychopathological explanatory concepts according to the preponderance of the recent research literature.

The empirical relationships between personality and marijuana use have contributed to understanding of several critical questions: why certain persons in a particular social context, say students at a given college, have had experience with marijuana while others in the very same setting have not; why certain persons in a particular setting may use marijuana in an experimental or occasional way while others may become more heavily involved with it; and, as we will see more directly in the later section on psychosocial development, why some persons, say in the very same high school class, begin use of marijuana early while others begin later. Questions about variation in marijuana use where the social environment is constant or controlled find logical answers in the kinds of personality or individual difference variation represented in the research just described.

Although this position about the role of personality variation is a general and even logical one, it is of interest to consider whether the specific attributes that have been linked with marijuana use are, in some sense, time-bound or historically parochial. For example, as marijuana use becomes increasingly pervasive and normative, is its use likely any longer to be linked with unconventionally? As it becomes decriminalized, is its use likely any longer to serve as an expression of sociopolitical criticism and repudiation of the established society? It should be obvious that the particular personality factors likely to be associated with any pattern of behavior depend upon the social meanings and definitions of that behavior; as the social definitions change—for example, as marijuana shifts to a normatively employed recreational drug—the personality factors should also be expected to change. Three likely exceptions to this kind of anticipation about the future are worth noting, however. First, marijuana use, like other problem behaviors, is age-graded; that is, it is seen as less acceptable for younger than for older youth. Thus, it is likely that early onset of use will continue to be associated with a general pattern of personality nonconventionality. Second, no matter how normative marijuana use becomes, some segment of the population will refrain from experience with it and, for this segment, strong personal controls having to do with religiosity or intolerant attitudes toward transgression will likely continue to be characteristic. And finally, while this cluster of personal controls may no longer be relevant to whether most people use marijuana or not, it may continue to be relevant in regard to the intensity of its use. The possibility that personal controls may have a key role in preventing marijuana abuse makes the relevance of personality a lively and continuing concern in future social policy about marijuana.

Marijuana Use and Behavior

A third major psychosocial domain with which marijuana use has been linked is the domain of social behavior. The most ubiquitous generalization that can be made is that marijuana use, far from being an isolated behavior, is generally part of a larger behavioral pattern involving the use of other drugs and engaging in a variety of other unconventional or nonconforming actions such as delinquency, sexual experience, political activism, and attenuated academic performance. An understanding of marijuana use as an integral element in a network of social behavior has large implications for social policy, both at the level of control and at the level of prevention or health promotion.

The linkage of marijuana use to the use of other drugs, both licit and illicit, is well established in nearly all studies that assess a variety of drugs. Further, the greater the involvement with marijuana or the frequency of its use, the greater the experience with other drugs (Goode, 1974a, b; Johnson, 1973; Johnston, 1975; Kandel, 1978a; O’Donnell et al., 1976; Rouse & Ewing, 1973). The positive correlations obtained among the various drugs is quite compelling evidence against the notion of drug substitution—that use of a given drug, say marijuana, would imply less use of another drug, say alcohol. Johnston (1975), for example, reports that the proportion of regular marijuana users in the Youth in Transition cohort who used alcohol on at least a weekly basis rose from 56 percent to 81 percent between 1970 and 1974, reflecting an increasing association in use of these drugs.

Recognition of the association between marijuana and other drug use has led to considerable interest in the order with which experience with different drugs takes place and to a concern with sequential developmental stages of initiation into the use of different drugs. O’Donnell et al. (1976) report that among their male cohorts between ages 20 and 30, alcohol was antecedent to the use of all the other drugs including marijuana. But for men who used marijuana and any of the other drugs (cocaine, opiates, heroin, sedatives, stimulants, or psychedelics), use of marijuana usually occurred first. Kandel’s research has also focused on this question (1975, 1978a; Kandel et al., 1978); her longitudinal surveys of New York State high school students suggest four “stages” in the progression from no drug use to the use of illicit drugs “harder” than marijuana: use of beer and/or wine; cigarettes or hard liquor; marijuana; and other illicit drugs. Of interest is her emphasis on the role of experience with the licit drugs as a necessary intermediate between the stage of no experience with drugs and the use of marijuana; whereas 27 percent of students who used tobacco and alcohol began initial use of marijuana by the follow-up period 6 months later, of those who had not used any licit drug, only 2 percent began (Kandel, 1975).

Both in terms of order of onset and of prevalence of use, marijuana emerges as a “boundary” drug between the licit drugs , like tobacco and alcohol, and the other illicit drugs. This key position of marijuana in a developmental sequence has raised the question of whether it serves as a “stepping stone” to the use of other illicit drugs. That use of marijuana is associated with a higher rate of experience with other illicit drugs has already been noted; what the stepping stone notion implies is that experience with marijuana has inexorable implications for progressing to other illicit drugs. Although this issue cannot be simply dismissed (see O’Donnell et al., 1976; Whitehead & Cabral, 1975), and although it is likely that engaging in the use of an illicit drug such as marijuana can stimulate the exploration of other illicit drugs, several considerations militate against assigning a “causal” role to marijuana use. First, the proportion of the population that has ever used marijuana is far greater than the proportion with experience with any of the other illicit drugs; thus, there is no inexorable progression. Second, as the data from the Monitoring the Future surveys show (Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 1978a), there has been an appreciable rise in marijuana use among youth in recent years without any concomitant increase in the proportion using other illicit substances. Third, it is logical to consider that the same factors that determined the use of marijuana may also influence the use of other illicit drugs, rather than the influence on those other drugs necessarily stemming from marijuana use itself. And finally, assigning cause to an antecedent permits an infinite regress in which it could be argued, for example, that since alcohol preceded marijuana, it is the more fundamental cause of other illicit drug use (see also Goldstein et al., [1975]).

The linkage of marijuana use to other drug use behavior is probably best seen as one aspect of a larger set of linkages between marijuana use and other kinds of behavior reflecting nonconventionality or deviance or what has been called “problem behavior ” (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Marijuana use in teenagers has been shown to be strongly associated with frequency of drunkenness (Wechsler & Thum, 1973; Wechsler, 1976; Jessor et al., 1973; Chase & Jessor, 1977); with sexual intercourse experience (Goode, 1972a; Jessor & Jessor, 1975); with delinquent or general deviant behavior (Johnston, O’Malley, & Eveland, 1978b; Carpenter et al., 1976; Elliott & Ageton, 1976a; Gold & Reimer, 1975; Jessor et al., 1973; Chase & Jessor, 1977); with activist protest (Jessor et al., 1973); and negatively associated with conventional behavior such as church attendance (Jessor et al., 1973; Chase & Jessor, 1977). For example, in the 1972 year of the Jessors’ study of high school youth, 44 percent of the males who had used marijuana were nonvirgins while only 17 percent of the males who had not used marijuana were nonvirgins; the corresponding figures for the females were 67 percent and 20 percent, respectively (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Among the young adults in the O’Donnell et al. (1976) study, users of marijuana were considerably more likely to report having committed criminal acts than nonusers, a finding similar to that for teenagers.

What these studies all sustain, without exception, is the covariation between marijuana use and other behaviors reflecting unconventionality. There appears to be a syndrome of unconventional or nonconforming behaviors in which marijuana use is a component part. These associations with other behaviors provide part of the social meaning of marijuana use; at the same time, they help reduce the possibility of arbitrariness in any decision to engage in the use of marijuana.

The emphasis in the preceding paragraph has been upon association, and no inferences have been drawn about the causal influence of marijuana on the set of related behaviors. The possibility that marijuana does play a causal role in relation to other behavior has been raised frequently in at least two areas—the area of crime and delinquency, and the area that has come to be called “the amotivational syndrome .” Both of these deserve comment. The literature on the question of whether marijuana use leads to crime or delinquency has been reviewed repeatedly (Goode, 1972b, 1974a, b, 1975; Elliott & Ageton, 1976b). Abel’s review (1977) found no evidence for a causal relation between marijuana and aggression or violence. The National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Use (1973a) concluded that marijuana neither instigated nor increased the level of crime and that the relation between marijuana use and crime or delinquency depended upon social, cultural, and psychological variables . Several studies involving youth find evidence that delinquency precedes involvement in drugs (Jacoby et al., 1973; Friedman & Friedman, 1973; Jessor, R., 1976; Johnston, O’Malley, & Eveland, 1978b). The longitudinal study of the Youth in Transition cohort provides an unusually compelling analysts of the relation of illicit drug use to delinquency in a nationwide sample of young men in high school. A five-category index of illicit drug use was related to measures of delinquency at each of five points in time. The longitudinal data enable the authors to show that the differences in delinquency among the nonusers and the various drug-user groups existed before drug usage; thus, they cannot be attributed to drug use. Their conclusion about the association between drug use and delinquency is that since both are deviant behaviors they are both likely to be adopted by individuals who are deviance prone, and deviance proneness is expressed through different behaviors at different ages—delinquency earlier, drug use later (Johnston, O’Malley, & Eveland, 1978b). This conclusion is consonant with the conclusions of Elliott and Ageton (1976b) who present a very perceptive analysis of the recent studies on the relationship of drug use and crime among adolescents. In rejecting the notion that marijuana use has a causal influence on delinquency, they argue that both delinquency and marijuana use are manifestations of the same phenomenon—involvement in deviance or problem behavior —and are associated with each other by virtue of a common relationship to social, psychological, and economic etiological variables. This seems a reasonable summary of the state of current research knowledge in this area.

The relationship of marijuana use to the so-called amotivational syndrome—apathy, poor school performance, career indecision—entails the same logical issues as the marijuana-crime relationship. Empirically, some cross-sectional relationship has been found between marijuana use and various indicators of the amotivational syndrome (Brill & Christie, 1974; Annis & Watson, 1975; Smith & Fogg, 1978; Mellinger et al., 1976, 1978; Jessor et al., 1973), although other studies have not (Marin et al., 1974; Johnston, 1973). Once again, longitudinal studies indicate that lowered academic performance, school dropout, and career indecision may antedate drug use. In a series of very interesting papers, Mellinger and his collaborators have explored the relation of marijuana use to grades, career indecision, and dropping out among a cohort of male freshmen followed over time at the University of California, Berkeley (Mellinger et al., 1976, 1978). They found no convincing evidence that use of marijuana had adverse consequences in these areas. Instead, as in the case of the marijuana-crime relationship, dropping out of school, career indecision, and grades, as well as the use of marijuana, appear to reflect common background factors and social values.

In relation, then, either to crime or the amotivational syndrome , no causal role has been established for the use of marijuana. The linkage of marijuana to these areas of behavior, as to other areas such as sexual experience, alcohol use, or activist protest, seems best explained as part of a behavioral syndrome of nonconformity related to a common set of social and psychological factors that represent proneness to deviance or problem behavior.

Marijuana Use and Psychosocial Development

Research on marijuana and psychosocial development has been especially illuminating because of its reliance on longitudinal design. Not only has longitudinal design enabled the disentangling of temporal order in issues such as those addressed in the preceding section, but it has also revealed that marijuana use—just as alcohol use or sexual experience —is an integral aspect of youthful development in contemporary American society. A comprehensive review of convergences in recent longitudinal studies of marijuana use and other illicit drugs has been prepared by Kandel (1978a); she has also edited a volume in which several of the studies are described by the investigators responsible for them (Kandel, 1978b).

A number of investigators have documented through time-extended studies that initiation or onset of marijuana use in samples of youthful nonusers is a predictable phenomenon based on social, psychological, and behavioral characteristics that are antecedent in time to its occurrence. The 5-year longitudinal study of elementary and secondary school students by Smith is a good illustration of this kind of research (Smith & Fogg, 1974, 1978, 1979). Relying on both self-report and peer rating measures focused largely in the areas of personal competence and social responsibility, these investigators were able to demonstrate, over a 4-year interval, significant prediction of onset versus no onset of marijuana use (Smith & Fogg, 1974), of variation in time of onset (early versus late) of marijuana use (Smith & Fogg, 1978), and of variation in extent of later use of marijuana (Smith & Fogg, 1979). A key predictor in their analyses has been a factor analytically derived rebelliousness scale, a measure that refers to the nonconventionality of personality discussed earlier in this paper. An interesting series of papers has also emerged from Sadava’s 1-year longitudinal study of nearly 400 Canadian college students (Sadava, 1973a; Sadava & Forsyth, 1976, 1977). Again, significant multivariate prediction of onset of use (and of other status changes such as discontinuation of use) has been demonstrated; these investigators rely on a field-theoretical approach that combines antecedent personality and environmental measures, as well as change scores on those measures over the time interval, as their predictors.

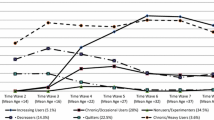

In terms of the content of the antecedent measures, there is strong convergence across these studies and others (Johnston, 1975; Kandel et al., 1978; Jessor & Jessor, 1978). The antecedent factors that are predictive of onset, time of onset, and extent of use are essentially the same ones that were reviewed in the earlier sections of this chapter as social environmental, personality, and behavioral correlates of marijuana use. Those nonusers who are more likely to initiate marijuana use, to initiate it earlier, and to become more heavily involved are already less conventional in personality attributes such as religiosity or tolerance of deviance, are more critical of adult society, have more friends who use marijuana and approve its use, and are more involved in other problem behaviors such as delinquency or excessive alcohol use.

This general pattern has been termed “transition proneness ” by the Jessors (Jessor & Jessor, 1977), a proneness toward developmental change that involves engaging in those age-graded behaviors that mark transitions in status from child to adolescent or from teenager to adult. Marijuana use is considered such an age-graded, transition-marking behavior, just as is the case for initiating alcohol use or becoming a nonvirgin, and this pattern of transition-prone attributes has been shown to predict onset of these other behaviors as well as the initiation of marijuana use. In this respect, the Jessors have sought to emphasize the developmental role that marijuana use plays and its commonality with other developmentally significant behaviors.

Two other aspects of the relationship of marijuana use to psychosocial development should be mentioned. First, the onset of marijuana use has been shown to be associated with systematic changes on the psychosocial variables that were predictive of that onset. Jessor et al. (1973) reported that residual gain scores over a year’s interval showed greater change on the predictor variables when marijuana onset occurred than when it did not (see also Sadava & Forsyth, 1976, 1977). Thus, change in marijuana behavior may be seen as part of a larger pattern of simultaneous developmental change. Second, it has also been shown, for high school youth at least, that time of onset of marijuana use over a 3-year interval is systematically related to the shape of the longitudinal trajectories or growth curves of a variety of the psychosocial predictor variables (Jessor, R., 1976; Jessor & Jessor, 1977, 1978).

Taken together, all of these longitudinal studies make clear that initiation into the use of marijuana, far from being an arbitrary event, is an integral part of psychosocial development among youth. Its onset can be forecast, and it can be shown that when onset does occur, its implications reverberate through the larger network of changes in personality and social interaction that are characteristic of growing up in contemporary American society.

Some Concluding Remarks

It seems safe to predict that marijuana use will continue to increase in prevalence in American society, not only among youth but in other age groups in the population as well. Its increasingly shared definition as a recreational drug, and the decreasing proportion of the population that disapproves of its use and that perceives any risk associated with its use, signal its likely institutionalization as part of ordinary social life. It is this anticipation that makes it even more important that research on marijuana be expanded; maximum knowledge about marijuana should be the context in which individual choice is exercised and personal decisions are reached about using it and about how to use it.

That use of marijuana is not without negative effects, for example, the impairment of driving skills, is already clear (Jones, 1977), and further research on both acute and chronic effects, especially of heavy use and of use in relation to other drugs, is important. The possibilities for studies of the effects of long-term use of marijuana in this country are increasing as cohorts that began use in the 1960s now have members with more than a decade of continuous experience with the drug.

Greater understanding would come also from research on the positive or beneficial outcomes of using marijuana. Although significant portions of the frequent marijuana users in a national sample of high school seniors acknowledged problems associated with its use—interfering with the ability to think clearly, causing one to have less energy, hurting performance in school or on the job (Johnston, 1977)—the general finding is that users tend to evaluate their experience as positive, pleasant, and beneficial (Goldstein, 1975; Weinstein, 1976; Orcutt & Biggs, 1975; Fisher & Steckler, 1974). Among the cohorts of men between 20 and 30, marijuana was the only drug for which more users reported the effect on their lives as good or very good than reported it as bad or very bad (O’Donnell et al., 1976). Since positive functions of use or reasons for use constitute a powerful proximal influence on actual use, further knowledge about the perceived benefits of using marijuana would seem important in understanding how continued use is sustained and how experimental use is initiated.

More research on the ethnography of marijuana use would also be useful. For example, Zimmerman and Wieder (1977) describe a particularly high-use context and point out that, in contrast to most occasions of alcohol use, a smoking occasion has no definite boundaries in time, and there appear to be no social sanctions controlling the amount of marijuana an individual may properly consume. Greater understanding of the informal rules, regulatory norms, and contextual expectations in which the use of marijuana is embedded would have relevance for efforts to develop alternative patterns of use more insulated against excessive or abusive practices.

The discontinuation of marijuana use is another topic of special research interest. In the 1977 national household survey, about half of the 26- to 34-year olds who had ever used marijuana reported no use in the past year (Miller et al., 1978). Whether this reflects the assumption of adult roles and the move out of a context of social support for use (Henley & Adams, 1973; Brown et al., 1974), or whether it reflects the fact that the involvement and experience with marijuana was only minimal and experimental in the first place (Hudiburg & Joe, 1976), it would seem crucial to establish systematic knowledge about factors conducive to the cessation of use of marijuana. These same factors may also be relevant to insulating against progression from occasional use to excessive use among those who do not discontinue. Longitudinal studies of adult development, with a focus on adult roles in relation to work, family, and childrearing and on adult social support for drug use, should illuminate the circumstances under which discontinuation is likely in that part of the life span.

The final research area that would seem to deserve special attention is that of the role of personal controls in relation to marijuana use. Personal control variables—whether religiosity, moral standards, or attitudes about transgression—were shown to be powerful in regulating whether marijuana use occurred at all, how early, and with what degree of involvement. As marijuana use becomes more widespread and normative, personal controls should come to play the key role in determining whether use remains moderate and regulated or becomes heavy and associated with other illicit drugs. A greater understanding of the nature and role of personal controls, and of their institutional, familial, and interpersonal sources, could conceivably contribute to the shaping of more effective prevention efforts against marijuana abuse.

Despite the importance of continued research on marijuana, it is clear that the kind of knowledge to be gained—as is true of the knowledge already in hand—will not yield univocal implications for social policy in relation to marijuana. Thus, one moves from research to social policy recommendations only with restraint. Nevertheless, in light of the research that has been reviewed and in light of the continuing increase in prevalence of marijuana use, it seems to be counterproductive to maintain its status as an illicit drug. The real problem with regard to marijuana has by now been transformed: Concern with its use should give way to concern with its abuse. But its continuing illicit status constitutes an almost insuperable barrier to educational and intervention efforts aimed at promoting moderate use and at forestalling abusive practices. Unlike the situation in the alcohol field, efforts to promulgate norms and expectations about socially acceptable marijuana practices are precluded, norms about appropriate time, place, and amount, and about inappropriate associated activities such as driving, and the simultaneous use of other drugs. The decriminalization of marijuana would open up opportunities for concerted societal efforts in this direction. Although decriminalization could itself bring a further increase in the use of marijuana, it does not necessarily follow, as Johnston, Bachman, and O’Malley (1978a) cogently point out, that the use of other illicit drugs will also increase. They call attention to the fact that the use of other illicit drugs has remained steady among high school seniors at the same time that marijuana use has increased significantly. A similar observation can be made with the data from the annual San Mateo surveys (Blackford, 1977). Action to cleave marijuana from the other illicit drugs would seem to be a timely item on society’s agenda; it would permit a salutary shift from an unsuccessful policy of prohibition to a policy of regulation that might have greater relevance for the minimization of marijuana abuse.

Policy initiatives in regard to marijuana—even the modest one suggested here—are obviously not easy to undertake given the politicization of the drug field as a whole. Recognition that the policies of the past were not based upon adequate empirical knowledge and therefore could not have been entirely appropriate would seem to be essential to creating a climate for change. Hopefully, this chapter has contributed an increment in that direction.

References

Abel, E. L. (1977). The relationship between cannabis and violence: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 84(2), 193–211.

Abelson, H. I., & Atkinson, R. B. (1975). Public experience with psychoactive substances: A nationwide study among adults and youth. Princeton, NJ: Response Analysis Corporation.

Abelson, H. I., & Fishburne, P. M. (1976). Nonmedical use of psychoactive substances. Princeton, NJ: Response Analysis Corporation.

Abelson, H. I., Fishburne, P. M., & Cisin, I. H. (1977). National survey on drug abuse, 1977. Princeton, NJ: Response Analysis Corporation.

Akers, R. L. (1977). Deviant behavior: A social learning approach (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Akers, R. L., Krohn, M. D., Lanza-Kaduce, L., & Radosevich, M. (1977). Social learning in adolescent drug and alcohol behavior: A Boys Town Center Research report. Boys Town, NE: The Boys Town Center for the Study of Youth Development.

Annis, H., & Watson, C. (1975). Drug use and school dropout: A longitudinal study. Conseiller Canadien, 9(3–4), 155–162.

Astin, A. W., King, M. R., & Richardson, G. T. (1978). The American freshman: National norms for fall 1977. Los Angeles: American Council on Education, University of California.

Blackford, L. S. (1977). Summary report—Surveys of student drug use, San Mateo County, California. San Mateo, CA: San Mateo County Department of Public Health and Welfare.

Braucht, G. N. (1974). A psychosocial typology of adolescent alcohol and drug users. In M. Chafetz (Ed.), Drinking: A multilevel problem. Proceedings, Third Annual Alcoholism Conference, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Washington, DC: U.S Government Printing Office.

Braucht, G. N., Brakarsh, D., Follingstad, D., & Berry, K. L. (1973). Deviant drug use in adolescence: A review of psychosocial correlates. Psychological Bulletin, 79(2), 92–106.

Brill, N. Q., & Christie, R. L. (1974). Marijuana use and psychosocial adaptation: Follow-up study of a collegiate population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 31(5), 713–719.

Brook, J. S., Lukoff, I. F., & Whiteman, M. (1977a). Correlates of adolescent marijuana use as related to age, sex, and ethnicity. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 50(4), 383–390.

Brook, J. S., Lukoff, I. F., & Whiteman, M. (1977b). Peer, family, and personality domains as related to adolescents’ drug behavior. Psychological Reports, 41(3), 1095–1102.

Brook, J. S., Lukoff, I. F., & Whiteman, M. (1978). Family socialization and adolescent personality and their association with adolescent use of marijuana. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 133(2), 261–271.

Brotman, R., & Suffet, F. (1973). Marijuana use: Values, behavioral definitions and social control. In National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse (Ed.), Drug use in America: Problem in perspective: Vol. 1. Appendix. Patterns and consequences of drug use. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Brown, J. W., Glaser, D., Waxer, E., & Geis, G. (1974). Turning off: Cessation of marijuana use after college. Social Problems, 21(4), 527–538.

Carman, R. S. (1974). Values, expectations, and drug use among high school students in a rural community. International Journal of the Addictions, 9(1), 57–80.

Carpenter, R. A., Hundleby, J. D., & Mercer, G. W. (1976). Adolescent behaviours and drug use. Paper presented at Eleventh Annual Conference of the Canadian Foundation on Alcohol and Drug Dependencies, Toronto, ON, Canada, June 1976.

Chase, J. A., & Jessor, R. (1977). A social-psychological analysis of marijuana involvement among a national sample of adolescents (pp. 1–99). (Contract No. ADM 281-75-0028). Washington, DC: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Commission (Canadian) of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs. (1972). Cannabis. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Information Canada.

Commission (Canadian) of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs. (1973). Final report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Information Canada.

Costa, F. (1977). An investigation of the relationship between psychological maladjustment and drug involvement among high school and college youth. Unpublished manuscript. University of Colorado, Boulder.

Cross, H. J., & Davis, G. L. (1972). College students’ adjustment and frequency of marijuana use. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 19(1), 65–67.

Elliott, D. S., & Ageton, A. R. (1976a). Subcultural delinquency and drug use. Unpublished manuscript. Behavioral Research Institute, Boulder, CO.

Elliott, D. S., & Ageton, A. R. (1976b). The relationship between drug use and crime among adolescents. In: Drug use and crime: Draft report of panel on drug use and criminal behavior. Research Triangle, NC: Research Triangle Institute.

Fisher, G., & Steckler, A. (1974). Psychological effects, personality and behavioral changes attributed to marijuana use. International Journal of the Addictions, 9(1), 101–126.

Friedman, C. J., & Friedman, A. S. (1973). Drug abuse and delinquency. In National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse (Ed.), Drug use in America: Problem in perspective. Appendix. Vol. 1. Patterns and consequences of drug use. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Gold, M., & Reimer, D. J. (1975). Changing patterns of delinquent behavior among Americans 13 through 16 years old: 1967–1972. Crime and Delinquency Literature, 7(4), 483–517.

Goldstein, J. W. (1975). Students’ evaluations of their psychoactive drug use. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 22(4), 333–339.

Goldstein, J. W., & Sappington, J. T. (1977). Personality characteristics of students who became heavy drug users: An MMPI study of an avant-garde. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 4(3), 401–412.

Goldstein, J. W., Gleason, T. C., & Korn, J. H. (1975). Whither the epidemic? Psychoactive drug-use career patterns of college students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 5(1), 16–33.

Goode, E. (1972a). Drug use and sexual activity on a college campus. American Journal of Psychiatry, 128(10), 1272–1276.

Goode, E. (1972b). Marijuana use and crime. In Marijuana: A signal of misunderstanding. Appendix. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Goode, E. (1974a). The criminogenics of marijuana. Addictive Diseases, 1(3), 297–322.

Goode, E. (1974b). Marijuana use and the progression to dangerous drugs. In L. L. Miller (Ed.), Marijuana effects on human behavior. New York: Academic Press.

Goode, E. (1975). Sociological aspects of marijuana use. Contemporary Drug Problems, 2, 397–445.

Gorsuch, R. L., & Butler, M. C. (1976). Initial drug abuse: A review of predisposing social psychological factors. Psychological Bulletin, 83(1), 120–137.