Abstract

Archival provenance is a complex concept, the sum of different factors that altogether trace archival records back to their creation and through their management and use. Provenance plays a major role in different archival functions, from arrangement and description to preservation. Therefore, principles and methods for capturing and representing provenance have been developed over a long time in the archival domain. However, further research in this area is needed to cope with the challenges and opportunities of new technology—on the one hand, the digital environment has made it extremely easy to mix and re-use digital objects, to a point that it is often difficult to trace provenance; on the other hand, tools like Resource Description Framework (RDF) can be used to represent provenance through new standards and models.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Arrangement and description

- Digital preservation

- InterPARES

- Original order

- Principle of provenance

- Provenance

- RDF

- Trust

1 Definition and Conceptualization

The International Council on Archives has defined Provenance as

[t]he relationships between records and the organizations or individuals that created, accumulated and/or maintained and used them in the conduct of personal or corporate activity. Provenance is also the relationship between records and the functions which generated the need of the records [1].

In other words, archival provenance refers to the origins, custody, ownership and use of archival objects. This concept is the basis for the Principle of Provenance—a pillar of Archival Science—which prescribes that archival documents should be arranged according to their provenance in order to preserve their context, hence their meaning.

The above is a simplification of a complex concept that has been investigated and debated by many scholars since the nineteenth century. In its very early stages, the principle of provenance was mostly meant not to intermingle documents from different origins, that is,

[r]assembler les différents documents par fonds, c’est-à-dire former collection de tous les titres qui proviennent d’un corps, d’un établissement, d’une famille ou d’un individu, et disposer d’après un certain ordre les différents fonds [2].Footnote 1

However, maintaining the identity of a body of records as a whole is not limited to identifying its distinctness in relation to other records. Archivists soon recognized that the internal structure of such a body also shapes the identity of a fonds, and thus was established the Principle of Original Order—a corollary of the Principle of Provenance. This principle established that groups of records should be maintained in the same order in which they were placed by the records’ creator. The underlying idea was that an archives “comes into being as the result of the activities of an administrative body or of an official, and […] it is always the reflection of the functions of that body or of that official” [3].

It was only 50 years ago that such conception was challenged by Peter Scott who—in a seminal article—laid the basis for a further refinement of the principle of provenance: in general, archives are not the result of a single creator who performs a set of specific functions. They are, rather, the outcome of a complex reality where different agents may act as creators; functions change, merge and disappear; and the internal structure is the result of recordkeeping activities that may have little relationship with the business activities of the creators. That is to say, the structure of an archives may have little or no correspondence with the structure of the creating organization. This approach led to a new understanding of the concept of provenance as it is now understood and accepted by the archival community—a network of relationships between objects, agents and functions.

In recent years, the meaning of provenance has been investigated further, and new perspectives have been proposed:

The similar notions of societal, parallel, and community provenance have also been advanced. They reflect an increasing awareness of the impact of various societal conditions on records creators and record creation processes at any given time and place across the records’ history. […] Some archivists have broadened the concept of provenance to include the actions of archivists and users of archives as formative influences on the creation of the records [4].

In particular, Tom Nesmith has provided a definition of provenance that—while giving rise to some issues due its very broad scope—may provide a basis for a broadened multidisciplinary perspective on provenance:

The provenance of a given record or body of records consists of the societal and technical processes of the records’ inscription, transmission, contextualization, and interpretation, which account for its existence, characteristics, and continuing history [5].

In conclusion, archival provenance is a complex concept, the sum of different factors that altogether trace archival records back to their creation and through their management and use.

2 Relationship to Current Research

This chapter now turns to discussing the author’s current research, which has a close relationship with the concept of provenance and focuses on these areas:

-

Trust and digital records. The author is a member of the InterPARES Trust research project, aimed at generating the theoretical and methodological framework needed to develop policies, procedures and regulations concerning digital records entrusted to the Internet, to ensure public trust grounded on evidence of good governance, and a persistent digital memory. Provenance is a crucial factor of evaluation when assessing the credibility of records on the Internet, therefore provenance needs to be investigated in order to shed light on the nature and the dynamics of the relationship between trust and provenance.

-

Digital preservation. InterPARES supports a number of research projects, and one of these is PaaST (Preservation as a Service for Trust), which is concerned with investigating digital preservation in the Cloud. The aim of this team is to design a model and a set of functional requirements for preservation of digital records in the Cloud, in order to provide insight and guidance to both those who entrust records to the Internet and those who provide Internet services for records. Preservation, including digital preservation, is about keeping objects along with the context that provides meaning to them. Provenance plays a major role in identifying and determining such context, hence supporting the definition of the identity of the objects targeted for preservation. In addition, provenance of digital objects is itself a digital object that also requires preservation. Both provenance and provenance of provenance are fundamental aspects in any preservation model, theory and practice.

-

Arrangement and description. Archival arrangement and description entails the creation of representation models in the archival domain. With a growing number of records being created and preserved using Cloud technology, there is a need to consider how to undertake their arrangement and description in the Cloud. Thus, InterPARES is also supporting research aimed at investigating how the Cloud environment may possibly affect arrangement and description theory and practice. Information on provenance is crucial in order to determine the creator of archival materials and identify records’ chain of custody, which in turn affect the way materials are arranged and subsequently described. Thus, provenance has an impact on arrangement and description. At the same time, representation models affect the way provenance is understood and represented in archival descriptions, because they highlight certain features while hide or obfuscate others. In short, provenance is a crucial dimension of any arrangement and description process.

-

Linked Data. Archives are no more made by simple, static documents in the traditional form of a written text on a piece of paper. Organizations and individuals—e.g., researchers—create and publish sets of open data that are then used, mixed and re-used. This raises an issue with regard to the reliability and authenticity of such data, which needs reliable and authentic information on provenance in order to be managed.

3 Motivations for Research

Provenance plays a major role in different archival functions:

-

Preservation requires maintenance of the context, that is, the complex network of relationships—along with the system of their meanings—in which archival objects have been created, managed and used. Provenance is by definition a crucial part of this context, because even its narrowest definition will address creation and custodial history (i.e., the chain of agents that held the materials, along with related facts and events).

-

Arrangement and description requires identification and proper description of both the creators and the chain of custody of archival materials. When arranging, provenance is the first clue to trace archival materials back to their origins, identify different bodies of materials, and get to a first, approximate grouping. When describing, the complexity of provenance may affect the representation of the archival materials—this is indeed more true in the digital realm, where new visualization tools and information models allow for greater freedom when designing archival descriptions. Moreover, materials on the Internet are not only dispersed but also mixed and re-used to a point that it is often difficult to trace provenance, hence to trust an archival resource. Some investigation is needed to understand whether traditional concepts and methods can be applied to identify and manage provenance on the Internet, thereby supporting proper arrangement and description of materials.

-

Access and use of archival materials is both welcomed and actively promoted by archivists. Provenance plays a role when accessing archival materials, since it is one of the key access points—in fact, the names of either the creator or the institution holding the archival materials are among the most common elements used in archival queries. Given a situation in which provenance is more and more a complex network of relationships—if not a confused tangle—it becomes important to allow users to understand such complexity without overwhelming them with a mass of information. Archivists are mediators—as such they have to provide a perspective. Archival representations of provenance in the form of descriptive finding aids form a major part of this perspective—that is why provenance needs to be thoroughly investigated.

-

Appraisal is the process of assessing the value of records for the purpose of determining the length and conditions of their preservation. According to a widespread approach (known as macro-appraisal), this archival function should be based on “extensive research by archivists into institutional functionality, organizational structures and work-place cultures, recordkeeping systems, information workflows, recording media and recording technologies, and into changes in all these across space and time” [6]. Provenance covers several of these factors, once we assume that it is more than just origination. Therefore investigation on the concept of provenance may have a direct impact on appraisal methods and principles.

-

Technology is not an archival function, however it is worth mentioning as a motivation for research on provenance, because it affects the way archival functions are interpreted and carried out. In particular, the extended adoption of the RDFFootnote 2 model and the general trend towards open government are changing the archival scene and impacting on objects and actors: datasets and distributed computing have entered the archival landscape, while IT specialists have started working on provenance from their perspective, developing their own principles, methods and standards. Therefore, it is important that archivists join the broader discussion bringing the archival voice to the table.

4 Capturing and Representing Provenance

Provenance of archival materials can be captured—most usually manually—from various sources. First of all, a diplomatic analysisFootnote 3 of the materials is the fundamental step to identify creators and any other agents that have had some relevant interactions with the materials. Then, reports, accession registers,Footnote 4 finding aidsFootnote 5 and any other document recording information on the creation, management and use of the archival materials may help in reconstructing its custodial history. Direct witness from any agents (creators, managers, archivists, users) may also be of assistance. The biography of the individuals, or the administrative history of the organizations that created and/or managed the materials along with information about their mandates and competences, also aids understanding of provenance. Knowledge of the history of the period during which archival materials have been created, managed and preserved put them in a broader historical context. The physical characteristics of the materials may be of some help as well. In the digital environment, metadata associated with or embedded into materials may provide relevant information on the provenance of either the materials themselves or the systems in which they reside. If the scope of provenance is broadened to include societal provenance,Footnote 6 the list of sources needs to be extended to include materials documenting aspects of both the society at large and the specific communities in which the materials have been created, managed and used.

Provenance is usually represented in finding aids in the form of either narratives in textual documents or data elements in software applications. Description should be carried out according to national or international standards, not only for the purpose of interoperability, but also because they usually include specific information elements conveying information on provenance. Even so, such information may be dispersed through different metadata elements or the model may not represent adequately the complexity of concepts like provenance and authenticity, as some scholars have suggested [7]. In recent years, new technology has pushed archival description towards redefinition of the traditional approach. RDF allows for an atomic fragmentation of data elements that can then be aggregated and represented adopting visualization techniques and strategies (e.g., graphs and graph exploration) never used before in the archival domain, dominated by written word, narrative and hierarchical diagrams. This opens up new opportunities for representing the complex network of relationships underlying—rather, making up—an archives, including the possibility of capturing additional layers of provenance in an automatic or semi-automatic way. At the same time, RDF poses new challenges, since it can be used to represent provenance through standards and models (e.g., PROV Ontology [8]) that are not specific to the archival domain, thus requiring a joint effort of different communities to develop shared solutions.

5 Research Challenges

The key challenge in establishing archival provenance is the identification of the creator. Organizations change, their denominations are modified, and so do their organizational assets, along with their mandates and competences. Archivists may have a very clear picture of what happened; nevertheless, they may have difficulties in deciding who the creator is because such decision depends on a discretional evaluation of the extent and depth of the changes [9]. The same is true for personal papers: there are no organizational assets to worry about, and changes of denomination are not the norm; however, individuals usually organize their records with more freedom than in a corporate environment. As a result, it may be difficult to establish the boundaries between the family archives, the archives of each individual belonging to the family, and the archives of the companies they were possibly holding. This happens because the principle of provenance is, indeed, uncomplicated and agreed in its very basic form (i.e., materials coming from different creators do not have to be mixed), but when it comes to its implementation is not always easy to implement because of the challenges associated with distinguishing whether an entity has died and a new entity has taken its place or it is the same entity that is just growing and re-shaping. As a result, identifying the creator, thus provenance, may be a hard challenge—as Duchein puts it, “[l]ike many principles […] it is easier to state than to define and easier to define than to put into practice” [9].

A more general issue is that there is no consensus within the archival community on the concept of provenance—some still think of it as referring to creation only; others include the custodial history of archival material in its scope, while more recent interpretations have taken into account communities and societies at large [10]. The approach proposed by Peter Horsman may serve to establish a common view. According to Horsman [11], the principle of provenance has an outward application, that is, it functions as a way to identify a body of archival materials as created by a certain creator (individuals, families, organizations), hence separated and distinguished from any archival materials in a repository or elsewhere. The principle has an inward application too, that is, it functions as a method to identify the internal structures of a body of materials, recreating the so-called original order. The key point is to identify the creators and recognize the different roles of any actor who dealt with the materials, i.e., managed, collected or used them. This is a fundamental step, because in the simplest case there will be a creator along with a chain of custody representing the story of different entities holding, managing, using and preserving the materials. In the most difficult cases, despite Duchein’s theorization it may be hard to distinguish who can be considered the creator of a complex archival fonds. Therefore, it is important to recognize the role and the contribution of all the entities that dealt with the materials.

In this regard, RDF may be key to the definition of an information model supporting different perspectives on provenance. RDF triples can be used to express specific types of relationships and establish different connections among entities. There would be no need to agree that certain elements are integral to provenance and to reject certain others, the story could simply be told, and the model for telling it could be made sufficiently compassing to allow everyone to tell their stories.

Another research challenge associated with provenance is the clear identification of some mechanisms by which it can support trust in a digital environment. There is no consolidated definition of trust in the archival domain—InterPARES Trust is working to this aim. However, it is agreed that trust is a multifaceted concept based on confidence, vulnerability and risk. Trusting an archival object has to do with the belief that such object can be relied upon. Such reliance is usually the result of a risk assessment—conducted either intentionally or not—where the significant properties of the object itself are analyzed and assessed. Provenance is one of the most meaningful properties contributing to such assessment; therefore, it contributes significantly to the trust-making process. However, besides abstract considerations, no analytic model, methods or metrics have been designed and implemented to support the evaluation of reliability of digital objects on the basis of information on their provenance. Prior to the digital era, archival materials were trusted because of their placement within a trusted repository, i.e., an archives, with preservation, access and use of documentary objects taking place in an environment or according to processes that were considered trustable. The digital environment has corrupted such belief. The challenge is to do something similar to what has been done with markup languages, i.e., making explicit what is implicit. Archivists and records managers need to retain control of provenance and make it explicit, so that users are aware of the quality of the objects and trust them accordingly. The challenge is to find models, mechanisms and tools to achieve this aim, solid enough to meet scientific criteria, but easy enough to be managed by users.

In general, use of new technology and models is another challenge, since it means that traditional archival models need to be compared and possibly integrated with the emerging ones. In this regard, co-operation with diverse communities is key, because the scene is populated by a variety of actors and users, all engaging with the same documentation, but possibly using domain-specific approaches.

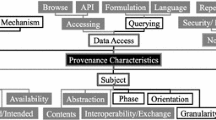

In conclusion, the fundamental topic that should be investigated may be: interoperable models to govern and represent provenance in a cross-domain environment. This is an umbrella theme under which different sub-themes may be investigated, such as: granularity and amount of information on provenance based on users’ needs and practices; characteristics of existing models of provenance; strategies to assess users’ trust in relation to the quality of information on provenance; and analyses of case studies.

Notes

- 1.

Transl.: Aggregate all different records in fonds, that is, group all the documents coming from the same body, institution, family or individual, and set the different fonds according to a certain order.

- 2.

Resource Description Framework.

- 3.

Diplomatic analysis is the critical examination of a record carried out on the basis of the principles and methods of Diplomatics. Diplomatics is the discipline that studies the form of written documents (i.e., their logical and physical characteristics) along with their genesis and textual tradition (i.e., how they came into being, and how they have been modified since their creation).

- 4.

An accession register is an administrative record documenting the process of transferring materials to a repository. It contains key information about the archival materials that have been taken into the physical custody of an archives.

- 5.

A finding aid is any description providing physical and intellectual control over archival materials, thus assisting users accessing and understanding the materials.

- 6.

Societal provenance is a term used to mean provenance in the broader sociocultural dimension. Records creation, management, use and preservation are sociocultural phenomena. Therefore, provenance should be interpreted taking into account the sociocultural dimension as the context in which all actions take place.

References

International Council on Archives: ISDF. International Standard for Describing Functions. First Edition. Developed by the Committee on Best Practices and Standards. Dresden, Germany, 2–4 May 2007. International Council on Archives, Paris (2007)

Instructions pour la mise en ordre et le classement des archives départementales et communales. Paris, 24 avril 1841. In: Lois, Instructions et Règlements Relatifs aux Archives Départementales, Communales et Hospitalières, pp. 16--28. H. Champion, Libraire, Paris (1884)

Muller, S., Feith, J.A., Fruin, R.: Manual for the Arrangement and Description of Archives, 2nd edn., trans. A.H. Leavitt. Society of American Archivists, Chicago (2003)

Nesmith, T.: Principle of provenance. In: Duranti, L., Franks, P. (eds.) Encyclopedia of Archival Science, pp. 284–288. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham (2015)

Nesmith, T.: Still fuzzy, but more accurate: some thoughts on the “Ghosts” of archival theory. Archivaria 47, 136–150 (1999)

Cook, T.: Macroappraisal in theory and practice: origins, characteristics, and implementation in Canada, 1950–2000. Arch. Sci. 5, 101–161 (2005)

MacNeil, H.: Trusting description: authenticity, accountability, and archival description standards. J. Arch. Organ. 7, 89–107 (2009)

World Wide Web Consortium: PROV-O: The PROV Ontology. W3C Recommendation 30 April 2013, http://www.w3.org/TR/2013?REC-prov-o-20130430/

Duchein, M.: Theoretical principles and practical problems of Respect des Fonds in archival science. Archivaria 16, 64–82 (1983)

Bastian, J.A.: Reading colonial records through an archival lens: the provenance of place, space, and creation. Arch. Sci. 6, 267–284 (2006)

Horsman, P.: Taming the elephant: an orthodox approach to the principle of provenance. In: Abukhanfusa, K., Sydbeck, J. (eds.) The Principle of Provenance: Report from the First Stockholm Conference on the Archival Principle of Provenance, 2–3 September 1993, pp. 51--63. Swedish National Archives, Stockholm (1994)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Bibliography

Titles already included in the References are not listed in the Bibliography.

Appendix: Bibliography

In order to acquaint those outside the field of archival science with archival thinking on provenance, what follows is a brief bibliography on the topic.

1.1 Selected Works

-

Cook, T.: What is Past is Prologue: A History of Archival Ideas Since 1898, and the Future Paradigm Shift. Archivaria 43, 17–63 (1997)

-

Schellenberg, T.R.: Modern archives: Principles and techniques. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1956)

-

Scott, P.J.: The record group concept: A case for abandonment. American Archivist 29, 493–504 (1966)

1.2 Short Bibliography

-

Abukhanfusa, K., Sydbeck, J. (eds.) The Principle of Provenance: Report from the First Stockholm Conference on the Archival Principle of Provenance. 2–3 September 1993. Swedish National Archives, Stockholm (1994)

-

Boles, F.: Disrespecting Original Order. American Archivist 45, 26–32 (1982)

-

Bearman, D.A., Lytle, R.H.: The Power of the Principle of Provenance. Archivaria 21, 14–27 (1985–186)

-

Brothman, B.: Orders of Value: Probing the Theoretical of Archival Practice. Archivaria 32, 78–100 (1991)

-

Douglas, J.: Origins: Evolving Ideas about the Principle of Provenance. In: Eastewood, T., MacNeil, H. (eds.) Currents of Archival Thinking, pp. 23–43. Libraries Unlimited, Santa Barbara, CA (2010)

-

Horsman, P.: The Last Dance of the Phoenix, or The De-discovery of the Archival Fonds. Archivaria 54, 1–23 (2002)

-

Hurley, C.: Problems with provenance. Archives and Manuscripts 23, 234–259 (1995)

-

Millar, L.: The Death of the Fonds and the Resurrection of Provenance: Archival Context in Space and Time. Archivaria 53, 1–15 (2002)

-

Posner, E.: Max Lehmann and the Genesis of the Principle of Provenance. In: Munden, K. (ed.) Archives and the Public Interest: Selected Essays by Ernst Posner, with a new introduction by Angelika Menne-Haritz, pp. 36–44. Society of American Archivist, Chicago (2006)

-

Sweeney, S.: The Ambiguous Origins of the Archival Principle of “Provenance”. Libraries & the Cultural Record 43, 193–213 (2008)

-

Yakel, E.: Archival Representation. Archival Science 3, 1–25 (2003)

-

Yeo, G.: Custodial History, Provenance, and the Description of Personal Records. Libraries & the Cultural Record 44, 50–64 (2009)

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Michetti, G. (2016). Provenance: An Archival Perspective. In: Lemieux, V. (eds) Building Trust in Information. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40226-0_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40226-0_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-40225-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-40226-0

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)