Abstract

Concepts relating to corporate sustainability (CS) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) have remained vastly under-explored in international entrepreneurship literature. The recent reviews by Jones et al. (2011) and Peiris et al. (2012) do not find a single study of CSR and indicate that sustainability is discussed in the traditional sense of the word in the literature (i.e. referring to the competitive advantage of companies), rather than as social responsibility and sustainability in a more holistic sense. The latter refers to the ‘triple-bottom line’, i.e. business that is sustainable from the point of view of the firm – profit, of the society – people, and of the environment and ecology – planet (see Elkington 1997). Moreover, in the Journal of International Entrepreneurship, only one paper (Kirkwood and Walton 2010) has during this decade considered the role of sustainability-related practices in international entrepreneurship. That study explored ecopreneurs in New Zealand through a case study, but we still do not have a clear view on whether it is worthwhile for internationalizing SMEs to invest their time and resources to develop socially responsible and sustainable business practices for foreign markets, as extant research on these topics in the context of international business overall tends to focus on large multinational enterprises (MNEs) rather than on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Jamali et al. 2009).

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Foreign Market

- International Performance

- Corporate Sustainability

- Corporate Social Responsibility Practice

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Concepts relating to corporate sustainability (CS) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) have remained vastly under-explored in international entrepreneurship literature. The recent reviews by Jones et al. (2011) and Peiris et al. (2012) do not find a single study of CSR and indicate that sustainability is discussed in the traditional sense of the word in the literature (i.e. referring to the competitive advantage of companies), rather than as social responsibility and sustainability in a more holistic sense. The latter refers to the ‘triple-bottom line’, i.e. business that is sustainable from the point of view of the firm – profit, of the society – people, and of the environment and ecology – planet (see Elkington 1997). Moreover, in the Journal of International Entrepreneurship, only one paper (Kirkwood and Walton 2010) has during this decade considered the role of sustainability-related practices in international entrepreneurship. That study explored ecopreneurs in New Zealand through a case study, but we still do not have a clear view on whether it is worthwhile for internationalizing SMEs to invest their time and resources to develop socially responsible and sustainable business practices for foreign markets, as extant research on these topics in the context of international business overall tends to focus on large multinational enterprises (MNEs) rather than on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Jamali et al. 2009).

While the research on CSR and sustainability in the activities of internationalizing enterprises has remained scarce, there are several reasons why this context is important to highlight. Firstly, internationalizing SMEs are resource-constrained by nature, lacking marketing resources (Knight and Cavusgil 2004). Thus, they may face distinct trade-off decisions in how to balance their resources towards internationalization and developing CSR and sustainability-related practices. Second, CSR in the SME context presents a unique phenomenon (Morsing and Perrini 2009; Perrini 2006), and SMEs also face distinct challenges when engaging in sustainable practices (Gelbmann 2010). Small firms also tend to view environmental practices as a burden rather than them being conducive to successful business (Revell and Blackburn 2007). All of these findings indicate that the impact of CSR- and sustainability-related practices on successful internationalization of SMEs is ambiguous and in need of further study.

Therefore, in this chapter, we seek to highlight these phenomena further by exploring the implications of sustainability for the performance of internationally operating SMEs. We continue in the next section by discussing the admittedly few extant publications dealing with the phenomena of CSR and sustainability in the context of SME internationalization and, due to its absence in the international entrepreneurship literature, we concentrate on how CSR and sustainability are viewed in the SME context in general. Subsequently, we introduce the research methodology, with the empirical results and discussion thereof provided further on. We conclude by assessing implications and limitations of the results, as well as potential future research avenues suggested in the present study.

CSR and Corporate Sustainability in the Internationalization of SMEs

CSR in the SME Context

The extant research on corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a construct could be criticized for being fragmented, considering that CSR has been defined and conceptualized in a multitude of ways in different streams of academic literature, which has created lack of clarity (see Dahlsrud 2008). Holme and Watts (1999) define CSR as ‘a duty of every corporate body to protect the interest of the society at large’, and we, while adhering to this definition, also note that CSR can be extended not only towards the society as a whole, but can also be focused on customers, employees, or the government (see Turker 2009). CSR is often examined through the theoretical background of institutional theory (Freeman 1984; Donaldson and Preston 1995), where organizations are recognized to manage a host of relationships with key stakeholders (e.g. customers and company shareholders, the local and national government, and the larger general public). A major implication therefore is that different type of shareholders, beyond the owners of the company, are considered important and taken into account when developing strategies (Neely et al. 2002) as the company aims to conform to the expectations and norms of different type of shareholders (Maignan and Ferrell 2004).

Much of the literature on CSR has been conducted in the context of large companies (Revell and Blackburn 2007). Research has often found CSR to be a unique phenomenon in management of SMEs, and most of the extant studies in the area have been mainly conceptual (e.g. Ciliberti et al. 2008; Gelbmann 2010). CSR may be distinct in the SME context both theoretically and managerially. In terms of theory, Perrini (2006) has suggested that when studying the impact of CSR in the SME context, distinct theoretical approaches may be needed, with Murillo and Lozano (2006) further highlighting the difficulties SMEs have in trying to conceptualize CSR in the first place. In terms of practical management of companies, Gelbmann (2010) has noted that communicating CSR- and sustainability-related practices to the stakeholder may be particularly challenging for SMEs due to their characteristics. Indeed, Perrini et al. (2007) also find that smaller firms tend not to incorporate CSR as formalized strategies, whereas larger conglomerates may do so.

Still, the few empirical results on the ways in which CSR impacts financial and growth outcomes in SMEs have tended to find a positive association. Longo et al. (2005) found that engaging in CSR practices may increase SME growth. Similarly, several other studies have also linked increased CSR-awareness to better financial performance (Buciuniene and Kazlauskaite 2012; Torugsa et al. 2012). In the context of internationalization, we identify two types of CSR that may be particularly relevant. One of these is the CSR exhibited by internationalizing SMEs towards their customers. As SME internationalization has been recognized to be network-driven (Johanson and Vahlne 2009; Johanson and Mattsson 1988; Coviello and Munro 1997), we might expect that extending socially responsible corporate behaviour towards customers would enable further exchange of knowledge through these relationships and consequently, increasingly successful internationalization. Here, we refer to ‘CSR towards customers’ (Turker 2009) and posit that:

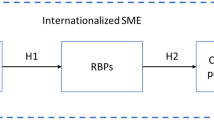

H1: The higher the corporate social responsibility of SMEs towards customers, the better their international performance.

A second type of CSR that could be expected to be beneficial for the global success of internationalizing SMEs might be CSR towards society. As outlined by Turker (2009), CSR towards society captures the willingness of a company to respond to the needs of the larger public, whether at national level or at local community level. Accounting for the needs of the local culture and for the expectations of the local employees, buyers, and institutional actors, is crucial when internationalizing, since distinct foreign markets may require SMEs to adapt to the cultural and societal expectations of that target market (e.g. Meyer and Skak 2002; Zhou et al. 2007). Internationalization at its core demands companies to adapt to the expectations of the target market at the product level (Knight 2001) as well as by aiming to adapt to the needs and expectations prevalent in the target market. In addition, internationalizing SMEs tend to lack resources, and often marketing resources in particular (Knight and Cavusgil 2004). Thus, exhibiting socially responsible behaviour may be a way for companies to achieve cost-efficient marketing (Jahdi and Acikdilli 2009). For internationalizing SMEs, these potential benefits may mean that positive word-of-mouth at the societal level offers them the possibility to commit their main resources elsewhere, for example to activities leading to successful foreign operations. Therefore, we also hypothesize that:

H2: The higher the corporate social responsibility of SMEs towards the society, the better their international performance.

In addition to CSR, exhibiting sustainable behaviour through strategies related to minimizing the ecological footprints of the company and its products should be assessed in the context of internationalization. For instance, Aragón-Correa et al. (2008) found that SMEs that are most proactive with their sustainability-related practices achieve higher performance. Sustainability can be achieved, for instance, through environmental innovation (Biondi et al. 2002), highlighting the fact that the extent of sustainability in companies may reside both at the product and at the overlying strategic level. Revell and Blackburn (2007) refer to ‘environmental performance’, and note that some managers may be reluctant to proactively improve it. However, here we are investigating how sustainability-related practices in SMEs impact their international performance and investigate sustainable practices at the company level. Environmental strategies may help SMEs increase their exports in general (Martín-Tapia et al. 2010), and therefore we suggest that adapting sustainable practices at the product level may also enable SMEs to internationalize more successfully:

H3: The higher the level of sustainability-related practices in SMEs, the better their international performance.

Research Methodology

Data Collection

We collected the empirical data during May–September 2014 via a cross-sectional web-based survey of Finnish SMEs. We drew up the initial list of firms to be contacted from the Amadeus online database, including the following industry sectors: forest industry, chemical industry, metal industry, other manufacturing activities and mining and quarrying, energy supply, water supply, waste management, and construction. This list resulted in 1130 SMEs in total, each of which were then contacted via phone and asked to participate in the survey.

During this process, we aimed to exclude non-suitable firms such as those without independent decision-making capacity (e.g. recently acquired by a larger company and/or made into a sub-branch or a subsidiary) and this resulted in the exclusion of 78 firms. Moreover, a total of 311 of the contacted SMEs declined to participate, citing lack of time as the most important reason for refusal. Similarly, despite several attempts to reach the most relevant decision-makers in the SMEs, 306 were not reached during the data collection process. In our opinion, a likely reason could have been the timing of the data collection: late June and July tend to be holiday season in Finland, which limits availability of both employees and executives at work.

The survey was developed by a group of researchers who translated the adapted scale items from literature to Finnish. A professional language editor was then employed to conduct a back-translation. The back-translated survey questionnaire was then compared with the original one in order to ensure that the items in the survey retained their intended meaning throughout the process. The questionnaire was then pre-tested with two managers in order to ensure that it was understandable to potential respondents.

The responses from the SMEs who had been contacted and who had agreed to participate in the survey were tracked down and two rounds of reminder e-mails were subsequently sent to those who had not responded: one round two weeks after the first contact, and another a week before the data collection was concluded.

The data collection process resulted in a total of 148 responses (14 % response rate, 148/1052). While we do not consider such a response rate a particularly high one, we note that it being above 10 %, there may not be much difference in possible non-response biases for any surveys with less than 80 % response rate (see Rogelberg and Stanton 2007). We further consider the length of the survey as a potential reason for the low response rate.

Of the final respondents, 61 % (91) have international operations and thus constitute the final sample for the purposes of this study. These SMEs had 58 employees on average, who were 34 years old on average, and the SMEs had been operating internationally for 20 years, on average.

Measure Development

We adapted the measure for CSR from Turker’s (2009) study. Specifically, we used a 7-point Likert scale to measure both CSR to society and CSR to customers, and applied principal component factor analysis with the varimax rotation method to develop the final scale measures used in the analysis. The resulted two-factor solution captured a total of 70 % of the total variation, with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) of 0.75 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity being statistically significant at the 1 % risk level. The factor loadings and communalities of the scale items are illustrated in Table 15.1. These two factors had Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.90 and 0.73, respectively.

As the extant literature does not go into detail on scales measuring the attitudes towards environmental sustainability in SMEs, particularly in the context of international entrepreneurship, we included a set of items partly adapted from Carter et al. (2000) from the context of environmental purchasing, but also included an exploratory set of our own items in order to help develop such a scale. The resulting one-factor solution captured a total of 64 % of the total variation, with KMO value of 0.78 and a significant Bartlett’s test (p < 0.01), and the Cronbach’s alpha value for the resulting measure was 0.86, indicating sufficient reliability. The factor loadings of the individual items varied between 0.7 and 0.9, with the communality values all being in the 0.5–0.8 range. The final scale items for the sustainability measure were as follows:

-

We pay much attention to the environmental hazards resulting from the manufacture of our products.

-

We apply a lifecycle analysis when we assess the environmental friendliness of our products.

-

Our products are part of the process of reducing environmental hazards and/or climate change.

-

Preventing damage to nature is a central goal of our business activities.

-

Production that saves natural resources is a central goal of our business activities.

For measuring international performance, we similarly used a subjective performance measure consisting of 7-point Likert-scale items accounting for managerial assessment on the degree of success that the SME had achieved in light of its internationalization. The one-factored result of the principal component analysis explained 79 % of the total variance, with a KMO value of 0.92 with Bartlett’s test of sphericity again significant at the 1 % risk level. In addition, the resulting seven-item scale exhibited sufficient reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95). Therefore, we deemed the measure for international performance sufficiently reliable and valid to be applied in our analysis. The final scale items were:

-

Generally speaking, we are satisfied with our success in the international markets.

-

We have achieved the turnover objectives we set for internationalization.

-

We have achieved the market share objectives we set for internationalization.

-

Internationalization has had a positive effect on our company’s profitability.

-

Internationalization has had a positive effect on our company’s image.

-

Internationalization has had a positive effect on the development of our company’s expertise.

-

The investments we have made in internationalization have had a good pay-back.

Finally, we also included relevant control variables by controlling for firm size (the number of employees) and firm age (in years). The descriptives and the correlation table of the variables used in the empirical analysis can be seen in Table 15.2.

Results and Discussion

The overall results of the hypotheses testing are illustrated in Table 15.3. The regression model including only the control variables (Table 15.3, model 0) was statistically significant, (F = 6.98, p < 0.01) with both the size (β = 0.27, p < 0.05) and the age (β = 0.23, p < 0.05) being positive and significant. Therefore, model 0 indicated that both size and age predicted increased international performance on their own, with larger, older SMEs having achieved better performance through foreign operations. This result could be seen as expected, since the internationalization efforts of SMEs tend to be restricted by their lack of resources (Buckley 1989; Burpitt and Rondinelli 1998), for example, marketing resources (Knight and Cavusgil 2004). Consequently, larger firms may be more likely to possess the human and financial resources to more fully fulfil their international and global strategies. Similarly, older SMEs may have had more time to acquire the foreign market knowledge that successful internationalization tends to require (Johanson and Vahlne 1977; Johanson and Vahlne 2009), and the experience gained over time by the management team of an SME may have a beneficial impact on internationalization of SMEs (Reuber and Fischer 1997). In our model, these variables predicted a total of 13 % of international performance among the SMEs (adj. R 2 = 0.13).

The second step saw the testing of the established hypotheses, positing that increased CSR to customers (H1) and to society (H2), as well as increased sustainability (H3) would predict increased international performance among SMEs. As seen in Table 15.3 (model 1), both CSR to society (β = 0.50, p < 0.01) as well as CSR to customers (β = 0.21, p < 0.05) predicted increased performance, and as the model remained statistically significant (F = 6.94, p < 0.01), H1 and H2 received support from the analysis. As the value for adjusted R 2 increased by 0.14, from the 0.13 in model 0 to 0.27 in model 1, the results suggest that the total explanatory power of CSR to the international performance was overall about 14 %. In addition to CSR having a positive impact on performance, the impact of CSR to society was particularly strong, with the coefficient β value being high and highly significant at the 1 % risk level.

Finally, higher levels of sustainability were not linked to increased international performance, as the coefficient for the former was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), and thus H3, postulating a positive relationship between the two, did not receive support from the analysis. In fact, the coefficient for sustainability was negative (β = −0.26), suggesting that less sustainable practices could be expected to lead to increased international performance instead. However, the correlation between the sustainability and performance variables was, while non-significant at the 5 % risk level, still positive (Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.15), and therefore as a whole we consider the results on the impact of sustainability on performance inconclusive.

Conclusions

International entrepreneurship literature has remained remarkably silent on concepts related to corporate sustainability (CS) and corporate social responsibility (CSR). There might be several reasons for this absence of research. The few existing studies on these topics suggest that international entrepreneurs may face particular trade-off decisions in how to balance their resources towards internationalization and developing CSR and sustainability-related practices. Also, CSR in the SMEs context presents a distinct phenomenon, and SMEs also face unique challenges when engaging in sustainable practices. Furthermore, small firms tend to view environmental practices as a burden rather than being beneficial to successful business. Based on these contradictions and the obvious gap in international entrepreneurship literature, the current paper sought to scrutinize these phenomena further, by exploring the implications of sustainability for the performance of internationally operating SMEs.

Much of the earlier literature on CSR overall has been conducted in the context of large companies, and is predominantly conceptual in nature. Only a very few empirical results exist on the ways in which CSR impacts financial and growth outcomes in SMEs. Therefore, our empirical study with data from internationally operating Finnish SMEs across several industry sectors provides an important contribution to the body of literature. Our results confirm that CSR, rather than sustainability-related practices, is positively linked to increased international performance of SMEs. Moreover, CSR related to society has the largest positive impact on performance, overriding even that of CSR towards customers. These results will provide further implications on the dynamics of CSR and sustainability in international performance, in particular highlighting their impact on successful SME internationalization.

Moving beyond our data, we can speculate that the interest towards CSR and sustainability is likely to increase among international entrepreneurs. Therefore, additional work bridging various countries and industries will be required to test the relationships we theorized, and to further discover whether the concepts and measures we applied on CSR and sustainability are appropriate in studying the performance of international entrepreneurial firms.

References

Aragón-Correa, J. A., Hurtado-Torres, N., Sharma, S., & García-Morales, V. J. (2008). Environmental strategy and performance in small firms: A resource-based perspective. Journal of Environmental Management, 86(1), 88–103.

Biondi, V., Iraldo, F., & Meredith, S. (2002). Achieving sustainability through environmental innovation: The role of SMEs. International Journal of Technology Management, 24(5-6), 612–626.

Buciuniene, I., & Kazlauskaite, R. (2012). The linkage between HRM, CSR and performance outcomes. Baltic Journal of Management, 7(1), 5–24.

Buckley, P. J. (1989). Foreign direct investment by small and medium sized enterprises: The theoretical background. Small Business Economics, 1(2), 89–100.

Burpitt, W. J., & Rondinelli, D. A. (1998). Export decision-making in small firms: The role of organizational learning. Journal of World Business, 33(1), 51–68.

Carter, C. R., Kale, R., & Grimm, C. M. (2000). Environmental purchasing and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Transportation Research Part E, 36(3), 219–228.

Ciliberti, F., Pontrandolfo, P., & Scozzi, B. (2008). Investigating corporate social responsibility in supply chains: A SME perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15), 1579–1588.

Coviello, N. E., & Munro, H. J. (1997). Network relationships and the internationalization process of small software firms. International Business Review, 6(4), 361–386.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91.

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks. The triple bottom line of 21st century. Oxford: Capstone Publishing.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gelbmann, U. (2010). Establishing strategic CSR in SMEs: An Austrian CSR quality seal to substantiate the strategic CSR performance. Sustainable Development, 18(2), 90–98.

Holme, R., & Watts, P. (1999). Corporate social responsibility. Geneva: World Business Council for Sustainable Development.

Jahdi, K. S., & Acikdilli, G. (2009). Marketing communications and corporate social responsibility (CSR): Marriage of convenience or shotgun wedding? Journal of Business Ethics, 88(1), 103–113.

Jamali, D., Zanhour, M., & Keshishian, T. (2009). Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in the context of CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(3), 355–377.

Johanson, J., & Mattsson, L.-G. (1988). Internationalisation in industrial systems – A network approach. In N. Hood & J.-E. Vahlne (Eds.), Strategies in global competition (pp. 214–287). New York: Croom Helm.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm: A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J.-E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40, 1411–1431.

Jones, M. V., Coviello, N., & Tang, Y. K. (2011). International entrepreneurship research (1989–2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 632–659.

Kirkwood, J., & Walton, S. (2010). How ecopreneurs’ green values affect their international engagement in supply chain management. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 200–217.

Knight, G. A. (2001). Entrepreneurship and strategy in the international SME. Journal of International Management, 7(3), 155–171.

Knight, G. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2004). Innovation, organizational capabilities, and the born-global firm. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2), 124–141.

Longo, M., Mura, M., & Bonoli, A. (2005). Corporate social responsibility and corporate performance: The case of Italian SMEs. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 5(4), 28–42.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(1), 3–19.

Martín-Tapia, I., Aragón-Correa, J. A., & Rueda-Manzanares, A. (2010). Environmental strategy and exports in medium, small and micro-enterprises. Journal of World Business, 45(3), 266–275.

Meyer, K., & Skak, A. (2002). Networks, serendipity and SME entry into Eastern Europe. European Management Journal, 20(2), 179–188.

Morsing, M., & Perrini, F. (2009). CSR in SMEs: Do SMEs matter for the CSR agenda? Business Ethics: A European Review, 18(1), 1–6.

Murillo, D., & Lozano, J. M. (2006). SMEs and CSR: An approach to CSR in their own words. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(3), 227–240.

Neely, A. D., Adams, C., & Kennerley, M. (2002). The performance prism: The scorecard for measuring and managing business success. London: Prentice Hall.

Peiris, I. K., Akoorie, M. E., & Sinha, P. (2012). International entrepreneurship: A critical analysis of studies in the past two decades and future directions for research. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 10(4), 279–324.

Perrini, F. (2006). SMEs and CSR theory: Evidence and implications from an Italian perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(3), 305–316.

Perrini, F., Russo, A., & Tencati, A. (2007). CSR strategies of SMEs and large firms, evidence from Italy. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(3), 285–300.

Reuber, A. R., & Fischer, E. (1997). The influence of the management team’s international experience on the internationalization behaviours of SMEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 4, 807–825.

Revell, A., & Blackburn, R. (2007). The business case for sustainability? An examination of small firms in the UK’s construction and restaurant sectors. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16, 404–420.

Rogelberg, S. G., & Stanton, J. M. (2007). Understanding and dealing with organizational survey nonresponse. Organizational Research Methods, 10(2), 195–209.

Torugsa, N. A., O’Donohue, W., & Hecker, R. (2012). Capabilities, proactive CSR and financial performance in SMEs: Empirical evidence from an Australian manufacturing industry sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(4), 483–500.

Turker, D. (2009). Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 411–427.

Zhou, L., Wu, W. P., & Luo, X. (2007). Internationalization and the performance of born-global SMEs: The mediating role of social networks. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 673–690.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and the Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Torkkeli, L., Saarenketo, S., Salojärvi, H., Sainio, LM. (2017). Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility in Internationally Operating SMEs: Implications for Performance. In: Marinova, S., Larimo, J., Nummela, N. (eds) Value Creation in International Business. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39369-8_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39369-8_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-39368-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-39369-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)