Abstract

Ecopreneurs are emerging as a new type of entrepreneur who are worthy of much greater consideration than has been given to date. The aim of this paper was to explore how a group of 14 New Zealand ecopreneurs engage with supply chain management issues of an international nature—namely importing, manufacturing and exporting. A case study method was used to collect data from face-to-face semi-structured interviews with the ecopreneurs and a wide range of secondary data such as industry reports, the company’s web sites and items from the media. On the supply side, ecopreneurs considered environmental and social costs of procuring from other countries. However, they had little power to influence supplier practices. Ecopreneurs also wanted to manufacture locally regardless of cost. Likewise, on the demand side, ecopreneurs assessed the environmental costs of exporting and were more in favour of selling locally due to their green values. The study found that various dilemmas of an environmental and social nature emerge as being important in the decisions and practices that ecopreneurs undertake with respect to managing their supply chain internationally. These dilemmas facing New Zealand ecopreneurs may offer a glimpse into future realities for other countries and businesses. We believe that these ecopreneurs are leading the way to a new frontier where environmental issues are likely to become increasingly unavoidable and should be considered in supply chain management. This exploratory research raises a number of important questions that require further research in order to more fully understand their implications for ecopreneurs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The field of ecopreneurship began to receive research attention in the late 1990s (Anderson 1998; Keogh and Polonsky 1998; Pastakia 1998), but is noted as being a field that is still in its infancy (Cohen and Winn 2007). Increasingly, entrepreneurs are recognising opportunities for new ventures as consumer demand grows for more eco-friendly products and services (Cohen and Winn 2007; Dean and McMullen 2007; Schaltegger 2002; Schaper 2002) and companies see that environmental marketing is a potential source of corporate reputation—and competitive advantage (Miles and Covin 2000).

The growth in ecopreneurs may be partially due to increasing market opportunities for sustainable products and services. Customers are becoming increasingly environmentally conscious (Laroche et al. 2001). Many are losing confidence in larger corporations and have expectations of companies to exhibit more social and environmental responsibility (Webb et al. 2008). A trend towards value-driven environmentalism has flourished since consumers started demanding and purchasing environmentally friendly products and services (Bansal and Roth 2000; Post and Altman 1994). Recent discourse on environmental issues such as climate change and carbon miles has raised awareness of the environment, and many people now choose to purchase with environmental sensitivity in mind (Anderson 1998). In response to this, many companies are recognising the need to become more green (Bansal and Roth 2000; Schaper 2002).

Indeed, Clemens (2006) recently noted that little research exists on the environment and small firms in general (see, for example de Bruin and Lewis 2005). Whilst there has been increasing research interest in ecopreneurs, there remains little empirical research (Freimann et al. 2005; Gibbs 2007). Where there has been useful related research, small sample sizes prevail. Authors to date have focused on single case studies (Dixon and Clifford 2007) or small samples of between one and ten cases (de Bruin and Lewis 2005; Freimann et al. 2005; Pastakia 1998; Schaltegger 2002). This research is similarly exploratory in nature but extends current research through using 14 empirical case studies of ecopreneurial businesses.

It is essential to begin this paper with the definition of ecopreneurs employed in this study. Ecopreneurs are defined as those entrepreneurs who enter these eco-friendly markets not only to make profits but also having strong, underlying green values. Thus, ecopreneurs are those who found new businesses based on the principle of sustainability (based on ideas from Issak 2002; Walley and Taylor 2002). This definition recognises that when someone founds a new business, they have the ability to shape their company from the outset (Schaltegger 2002). Thus, our view is that ecopreneurs bring their own green values with them into their new business. To borrow from Freimann et al. (2005), it may be easier to ‘infect’ founders with ideas of sustainability.

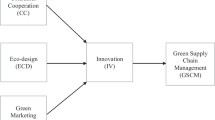

The overarching objective of this study was to explore how ecopreneurs’ green values affect their international engagement throughout the entire supply chain—with importing, offshore manufacturing (supply side decisions) and exporting (demand side decisions). Like ecopreneurship in general, these research questions have received little direct attention. To this end, our research questions are broad and aimed at gaining an overview of whether these ecopreneurs engage in international supply chain decisions and their views on such decisions.

-

1.

Supply side decisions

-

(a) How do ecopreneurs engage with importing raw materials and supplies? What are their views on importing?

-

(b) Do ecopreneurs engage in offshore manufacturing? What are their views on offshore manufacturing?

-

-

2.

Demand side decisions

-

(a) Do ecopreneurs export their goods? How do ecopreneurs feel about exporting?

-

First, the relevant literature on supply chain management is reviewed. Whilst both the supply chain management (SCM) and internationalisation literatures are vast, our focus is on small firms and entrepreneurs’ internationalisation decisions in relation to SCM.

Literature review

Studies have found a number of factors involved in whether a company chooses to address environmental supply chain management practice. These triggers have been both reactive and proactive. First, many companies have only implemented green purchasing strategies as a reactive measure to meet enforced standards (such as government regulation) or public debate (e.g. regarding child labour; Eiadat et al. 2008; Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004; Min and Galle 1997; Walton et al. 1998). On the other side of the supply chain, customer demand and market opportunities (Eiadat et al. 2008; Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004) have driven the implementation of environmental supply chain management. Within companies, the degree to which environmental causes are embraced depends on whether managers have a concern for the natural environment (Carter et al. 1998; Eiadat et al. 2008; Ramus 2002). Barriers to implementing green purchasing are primarily around the cost (such as environmental programmes and recycling; Min and Galle 1997). The literature review focuses on the supply and demand side factors around small business internationalisation in particular, but draws on studies of larger firms where relevant.

On the supply side, supply chain management can play a significant role in reducing the environmental impact of companies (Wycherley 1999). This is evidenced in the rise in attention companies have given to environmental supply chain management in recent years (Coté et al. 2008; Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004; Simpson and Samson 2008). There is a growing view that along with its own environmental practices, a company is also responsible for its suppliers’ environmental management (Christmann and Taylor 2002). Thus, green/environmental purchasing has emerged alongside growing concerns for the environment (Min and Galle 1997) and has been found to differ between countries. German companies (known to be highly environmentally conscious) engage in this more extensively than those in the USA for example (Carter et al. 1998). Specifically, some companies place demands on conditions at the suppliers’ premises (such as pollution, child labour, and chemical use), the purchase of organic raw materials and less hazardous chemicals for their own plant, and insisted on changes to suppliers’ processes or products (Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004).

In perhaps one of the most well-known, early examples of companies showing environmental concerns, The Body Shop was distinctive in the way it purchased supplies with the environment in mind (Wycherley 1999). Suppliers viewed The Body Shop as having a solid commitment to the environment as well as a good relationship with their suppliers—two factors essential to a green supply chain. Interestingly, many of these suppliers believed that few of their other customers were interested in green products. This would suggest that the size of the customer’s order with the supplier matters in their adoption of environmental practices (Walton et al. 1998). In fact, one recent study found that suppliers did not want to put resources into improving their environmental performance unless it related specifically to their core function—manufacture or supply of a service (Coté et al. 2008). Companies may also use different environmental practices depending on the supplier (Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004; Wycherley 1999) and have different strategies for managing suppliers (Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004). The size of the customer may too impact on the extent suppliers adopt environmental practices (Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004). However, even in a large company such as The Body Shop (which clearly has the potential to impose environmental standards on their suppliers), interviews with their suppliers found that the environmental standards required depended on the importance of the supplier to the supply chain (Wycherley 1999). Whilst first-tier suppliers may be influenced by a company’s environmental requirements, this may not extend further up the supply chain. For instance, The Body Shop did not have enough volume of business to be able to influence second-tier suppliers—such as the chemical industry (Wycherley 1999).

Along with decisions about sourcing of supplies, another area where environmental issues may arise is in manufacturing practices (Crowe and Brennan 2005; O’Brien 2002). O’Brien (2002) argues that it is implicit that all manufacturing processes should use minimum amounts of energy and produce minimal waste—although this view may be rather optimistic. One way that companies can show their commitment to environmental standards is to adopt a formalised approach to environmental management such as ISO14001 (Crowe and Brennan 2005). ISO 14000 is known to offer benefits to both the company’s environmental management system as well as its overall performance despite being negatively perceived by many firms (Montabon et al. 2000). Other companies may have a different view of manufacturing practices. Similar to the case for suppliers mentioned above, environmentally based manufacturing strategies have been found to be used by some companies as a strategic opportunity. O’Brien (2002) concluded that by promoting environmental responsibility, companies may be able to exploit a growing market for such products. However, these studies generally deal with larger established firms; very little research focuses on the situation for small firms.

On the demand side of the business, an ecopreneur has to sell their product or service. Recent discourse on environmental issues such as climate change and carbon miles has raised awareness of the environment, and many people now choose to purchase with environmental sensitivity in mind (Anderson 1998). This trend has led to an increasing interest in green/environmental marketing (Peattie 2001; Prakash 2002; Straughan and Roberts 1999). As well as marketing strategies, like any entrepreneur, ecopreneurs must make decisions about exporting and internationalisation. Not all firms choose to export their products, and those who do have a range of different motivations (Chetty and Campbell-Hunt 2003). Chetty and Hamilton (1993) suggest that exporting is an “expensive, risky and lengthy process involving a complex amalgam of perceptions, intentions, competencies and characteristics” (Chetty and Hamilton 1993, p. 255). A recent literature review (Leonidou 2004) found that there are a number of barriers that hinder small businesses from exporting. External barriers such as those of procedures, government, task and environment combine with internal factors such as information, functional and marketing to inhibit export development. For others, resource limitations are strong barriers, along with lifestyle considerations (Fillis 2004).

Within the small firm context, the role of managers and/or owners has been found to be significant with respect to internationalisation (Chetty and Campbell-Hunt 2003; Crick et al. 2006; Hutchinson et al. 2007). In their model of entrepreneurial internationalisation, Jones and Coviello (2005) suggest that entrepreneurial behaviour is an important component in the internationalisation decision and is impacted on by the personal competencies and resources of an entrepreneur (Jones and Coviello 2005). Others agree that personal factors are important—such as the owner’s perceptions of the international business environment (Manolova et al. 2002), their vision, personality and background (Hutchinson et al. 2007), managerial skills (Manolova et al. 2002), experience in other countries (Hutchinson et al. 2007; Manolova et al. 2002) and their networks (Hutchinson et al. 2007). Following this line of argument means it often comes down to one individual (the entrepreneur) who makes the decision about whether the business will internationalise. Thus, an ecopreneurs’ ecological orientation (Freimann et al. 2005) may be highly significant to what is referred to as an international entrepreneurial orientation (Kuivalainen et al. 2007). Entrepreneurs’ strategies for internationalising are likely to be less pre-conceived and planned than in larger companies (Chetty and Campbell-Hunt 2003). Whilst founders/managers of small firms are vitally important to initiating the internationalisation decision, conversely they have the potential to be an inhibitor to internationalising (Chetty and Blankenburg Holm 2000).

In summary, as can be seen to date, environmental aspects of internationalisation have not emerged strongly as a factor in the extant research (Freimann et al. 2005). Two studies are, however, worthy of more mention as they may offer some insights into the possible behaviours of ecopreneurs. First, in Leonidou’s (2004) literature review of 32 prior studies, there was no mention of environmental concerns or founder/managers’ values in the vast range of export barriers found. The closest mention would be the excessive transportation costs which were found to be of high impact in an aggregate ranking of factors. Thus, it could be inferred that environmental impacts were not a concern. In a study of craft-based businesses, Fillis (2004) found that existing internationalisation theory did not sufficiently explain the behaviours of these firms. Some had ‘feelings’ for their products and did not necessarily have a market orientation, but were more focused on the overall quality of their life. This led to the philosophy of the owner being dominant over external influences, and the firms did not follow the typical progression though stages of export development which other firms exhibit (Fillis 2004). It is from this relatively limited base of extant research which we have placed the current study. As noted earlier, a key focus of our study’s findings and conclusions is based around extending our scant knowledge of how ecopreneurs manage their supply chain on an international basis, and we aim to contribute to this emerging literature.

Methods

Given the limited understanding we have of ecopreneurship to date, a qualitative research method was considered to be the most appropriate approach for this study. Qualitative approaches are particularly useful in areas that are not well advanced theoretically (Edmondson and McManus 2007). Case research is one manner of achieving such advancements and are useful in addressing research which has explanatory questions such as the ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions (Yin 1984). Yin (1984) concludes that different types of research question demand different research strategies. Research involving explanatory questions requires a need to make operational links over time, and case studies are appropriate. Case studies therefore differ from other research approaches which are intent on answering how, what and how much questions, which focus on measuring frequencies or the incidence of an event (Yin 1984). Theory development is the aim of this study, in addition to the usual description questions such as what, how, when and who (Bacharach 1989; Whetten 1989). We use Eisenhardt’s (1989) method and process for building theory from cases that is “highly iterative” and “tightly linked to data” (p. 532).

Sample selection

The sample arose from businesses we heard were operating in Dunedin, from searching websites such as Ecobob (www.ecobob.co.nz) and companies’ own web sites. Prior to the interviews, the authors conducted a literature review (summarised above) to understand the extant research on ecopreneurs. As noted, this field is an emerging one and does not yet have a substantial literature base. A semi-structured interview schedule was drawn up and one pilot interview (with two ecopreneurs from a local company) was conducted by the two authors and a research assistant. The purpose of this interview was to help understand the main issues that the ecopreneurs felt were important and therefore aided us in developing the questions for the 14 case studies. The questions were designed to be broad and open-ended to gauge individual opinions.

Our research involves interviews with founders of 14 different eco-businesses that could be classified as meeting our definition of ecopreneurs. Either one or both of the authors interviewed the participants in a face-to-face format. There were 17 participants in total because in three of the companies, two ecopreneurs were both present at the interview (refer to Table 1).

The semi-structured interviews were held in three of New Zealand’s larger cities—Wellington (North Island), Christchurch and Dunedin. One ecopreneur in a rural town was also interviewed (South Island). Whilst the interviews were spread over both islands of New Zealand, we do not see there to be any significant differences between these locations that would impact on the findings of this study. We purposefully selected ecopreneurs in a wide range of different industries given the limited understanding of ecopreneurs to date. Ethical approval was gained for this study from the University of Otago Ethical Committee. The researchers gained approval from the companies to be identified, but for the purposes of confidentiality, we do not identify individuals with the direct quotes in the discussion. However, full names of the companies are listed in Table 1. Interviews ranged from 40 min to 1 h and 50 min. Most of the 14 interviews lasted approximately 1 h and 10 min, and all were tape-recorded and transcribed. In total, 17 h of interviews were conducted. Additionally, information from secondary sources such as media reports, industry statistics, company web sites and promotional material were gathered to supplement the interviews. Eighty-eight such documents and reports were analysed for the study.

Before presenting the findings, some notes on the demographics of the sample are useful (refer also to Table 1). The businesses were relatively small, employing on average five full-time staff and 0.5 part-time workers. Half of the businesses had an annual sales turnover of less than $100,000 and only three businesses had sales over $1 million (1 NZ dollar = 0.46 GBP). This is partially due to the newness of the businesses studied—the majority had been in business less than 3 years. The nature of their products and names of the companies are shown in Table 1. Names have not been disguised as full permission was given to use the companies’ identities in the study.

Data analysis

The QSR NUD*IST Vivo (Nvivo) software package was used to manage the data. Transcripts were coded according to themes and analysed using a constant comparison approach (Glaser 1992). The data were coded by paragraph and sentence as proposed by Strauss and Corbin (1990). Code notes were initial thoughts about themes and possible relationships and issues that appeared important to the participants. Reliable methods and valid conclusions are essential to any good piece of research. In this study, the issue of credibility and transferability was addressed in three main ways: using convergent interviews and native categories (those the participants use), selecting quotes and contrary cases and in the use of tabulations. The issue of dependability was also addressed in three ways: inter-coder agreement, field notes and tape recording the interviews.

As with any research methodology, there are some weaknesses with using case studies. Yin (1984) poses three main pitfalls: case studies can lack of rigour; they are not generalisable in the traditional scientific way; and, finally, they can be unruly, involving vast quantities of data and are often time-consuming and lengthy pieces of work. We believe that these weaknesses are inevitable given the developmental stage that the field of ecopreneurship is at present. This study aims to explore broad issues around ecopreneurship and international engagement with supply chain management and poses research questions for further exploration. It is only after more extensive research has been undertaken that generalisability will become possible.

Key findings

Country context

Before the key findings are outlined, the country context for the study must be considered. This study was conducted in New Zealand (population four million). New Zealand is a country of small to medium enterprises (SMEs). SMEs are those with 19 or fewer employees (Ministry of Economic Development 2007). New Zealand is widely regarded as being highly entrepreneurial compared to other countries (Frederick and Chittock 2006). New Zealand also has a reputation of being ‘clean and green’, and this is important to the study of ecopreneurship (for a more extensive explanation of New Zealand’s environmental climate with respect to entrepreneurship, see de Bruin and Lewis 2005). One of the key branding images used by the Tourism New Zealand is of being “100% Pure”. Such by-lines are accompanied by images depicting the ‘pristine’ natural environment of New Zealand. There are also distinct issues around internationalisation, such as geographic isolation. These characteristics are important to explore as they affect the climate for ecopreneurship and should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. New Zealand is geographically isolated and is dependent on importing and exporting. Exporting is still, however, conducted by a minority of firms—particularly in smaller firms (Chetty and Blankenburg Holm 2000).

As noted in “Introduction”, our research objective and research questions were relatively broad due to the exploratory nature of the research. Thus, it was our purpose to explore whether and how ecopreneurs dealt with both supply side and demand side supply chain management issues. These findings are discussed in turn: importing, manufacturing, exporting and opening branches offshore and are summarised in Table 2.

Supply side decisions

A number of the ecopreneurs faced many dilemmas in trying to balance their green values with their profit objectives when organising suppliers for their business. When faced with importing supplies from overseas, there are obvious environmental concerns with the transportation of goods. Table 2 indicates those ecopreneurs who imported some products from overseas. They faced environmental dilemmas as noted by the following two ecopreneurs:

The choice between buying an environmentally friendly product and buying a slightly less environmental—like a panel from China for instance—we would buy the best one that we thought we could get, the greenest one we thought we could get.

We’re looking at importing more, distributing…the [product] that we’re bringing in because we find that they’re one of our best sellers and then to bring in other products, to get them into shops and then eventually we drop those products and just make our own.

Some of these ecopreneurs also had concerns of a more social nature. Importing products from countries that used differing forms of labour, production and management methods (such as child labour) was problematic for many ecopreneurs. For example, one ecopreneur sells organic household goods and when looking for suppliers faced the difficult decision about whether to select the ‘cheapest’ organic option or take a more expensive option that was produced under better conditions. Thus, the environmental issue (i.e. organic) was often considered along with the social implications of decisions (human rights issues, child labour, working conditions, etc.). These importing decisions may differ from other entrepreneurs who would look for the economies of scale for manufacturing offshore or importing from overseas countries.

Do you lose a big contract like that on your values or do you go to China, do you find it, I mean there are reputable companies in China now producing organic cotton products but I think if I was to do that, it’s a huge amount of research that has got to go into it to make sure that what they say is true, that all the organic certifications are up to scratch, that they’re not using any child labour and then that’s a whole new field to have to consider.

Another ecopreneur commented that she was initially quoted for getting bags made in China, but felt that it was not in fitting with what she wanted to achieve:

Right, what do I have to do that’s different to the bags that are already out there. So that was when I came back to a New Zealand made bag and that was when I started thinking right, a sustainable business. So while it was a kind of a, an environmental product if you like and trying to reduce the number of plastic bags, I then thought right, I have to take it that next step further and actually have a credible product and sort of know who my suppliers are and choose you know, people who have got environmental management systems in place through my supply chain, making things as well and do it as best that way as I can.

Being made in New Zealand was seen as the sustainable (both socially and environmentally) option, but also a branding mechanism too. A related issue for many ecopreneurs was the decision to have their products manufactured locally or offshore where cost savings were often evident. As Table 2 indicates, most ecopreneurs made decisions to manufacture their products themselves in New Zealand. This decision was philosophically based and was not related to price. The ecopreneurs generally believed that manufacturing locally was one of the key components to their business. One comment indicates this: “I do like to support New Zealand products…New Zealand-made as much as I can”. In another example, an ecopreneur faced a number of options for making products offshore. Indeed, one of her friends commented that it would be easy to deceive customers (legally) into believing it was New Zealand made:

He said, why don’t you get it all manufactured in China and you know bring it back here and put your own ingredients into it and then you can called it New Zealand made. I think if the cost of the ingredients that you’re putting into is just over half the total cost, then you can say it is made in New Zealand and I didn’t like that idea at all. I thought it was totally dodgy and that’s when I started going up the green path.

Going up this green path was somewhat problematic for this ecopreneur and others as it was often difficult to find someone locally to manufacture their products (particularly in the small quantities required to start with). Indeed, she found that some local manufacturers did not share her view of what constitutes ‘natural’, as illustrated by this excerpt:

We wanted to be New Zealand based business, who had the same philosophy as us and that were producing natural products. That proved to be quite difficult because we went to see a few and got samples made by them and they were trying to sneak in ingredients that weren’t really what we called natural.

Often, this desire to manufacture in New Zealand was a significantly more expensive option than manufacturing offshore, but it was considered to be important to the ecopreneurs that their products were New Zealand-made. This is bucking an ongoing trend to market products as ‘designed’ in New Zealand but made offshore. Interestingly, some ecopreneurs noted that customers were not typically concerned with where the product was made as long as the product itself was environmentally friendly. For example,

I mean we’ve just started on our bamboo and a lot of people are really interested in that because bamboo is such a new concept…they don’t care where it’s made, it’s because of what it is.

This quote illustrates that there seems to be an awareness of bamboo as being environmentally friendly. Furthermore, the ecopreneur discussed that in their experience, customers who purchase eco-friendly products also seem to be quite price-conscious. Continuing with the same example, the ecopreneur illustrates that this price consciousness had an important flow on effect for her business. She had to decide whether to turn down orders because of her desire to manufacture the bulk of her products locally:

The thing with China is that it is very hard, it was actually a really hard decision to make because at the bottom line, if people want to get something.…I believe they just want the better price so what do you do?

This obviously created a dilemma for the ecopreneur who realistically could not grow her business much more without importing more (as noted earlier) and manufacturing more products offshore. In total, half of the ecopreneurs in our study believed that the price of their products and services was a barrier to customers adopting them. This quote illustrates the viewpoint:

There’s not enough people that would be prepared to pay a premium just because it’s the right thing to do. They have to still see that it is a good product.

Generally, whilst customers may want to adopt more eco-friendly products and services, they are constrained by budgets. Ecopreneurs are often competing with businesses offering mainstream products and services in tender-type purchasing decisions. This price consciousness and the seeming apathy about whether or not the product was made in New Zealand meant that ecopreneurs often could not sufficiently capitalise on the local manufacturing aspect and essentially could not pass on all of the increased costs to consumers. Indeed, one ecopreneur noted:

[Design is] not an excuse to elevate your pricing but you know you have to have some justification for it because you can’t just make stuff here and compete on the price.

In other cases, the decision of whether to manufacture locally or offshore was made for ecopreneurs when the technology required to make a particular product was not available in New Zealand or it was a unique product, like Fair Trade. For example:

One of the other products that I’m looking at, at this stage cannot be manufactured here. So it would be a matter of bringing it in and then marketing it here. So until that technology is here then it would have to be made offshore.

We’re looking at going more global with the idea that we’ll import from countries with fair trade like from India and places like that.

In other cases, a combination of manufacturing in New Zealand and countries like China was utilised. An online eco-store explains the rationale for this more fully:

We do our own children’s toys, we make our own range of those and we’re looking at going offshore now because there’s quite an interest with the hotel chains to have eco-rooms and they want to source towels and sheets and so we’re looking…at going offshore [India].

Demand side decisions

Ecopreneurs also had to contemplate where to sell their products and services. As Table 2 indicates, most of the companies exported a small amount of their products offshore. Exporting is a key way of growing a business in New Zealand due to the small domestic market (Corbett and Campbell-Hunt 2002). One ecopreneur notes his plans to sell organic beer into Australia first and then America as being driven by the fact that “New Zealand is small, so [we] need to tap into larger markets”. However, decisions to export created an interesting dilemma for some of the ecopreneurs. They had to look offshore to sell their products, but exporting created a potentially wide environmental impact. Some of the ecopreneurs did not export and could not justify this because their business was based around selling local produce and New Zealand-made products (such as locally grown organic vegetables).

Whilst mainstream companies in New Zealand may be concerned about the monetary transport cost of exporting, ecopreneurs were concerned also with the environmental costs of transporting products to the other side of the world. The issue of freight and its related carbon emissions was the main concern of those who exported or were contemplating exporting. In one case, they chose to make a decision to use the best transport option available to them—shipping—but this was chosen over air freight. Even so, in the quote below, they recognised the environmental impacts of the operational decisions:

So the exporting we’re doing now is frozen yoghurts to the US. We started that this year and we sent a number of containers so that’s surface freight…very dependent on oil and carbon emissions really.

Others with less bulky products were able to export with greater ease and less impact on the environment. For example, the flax paper made by one ecopreneur was coveted by consumers around the world:

I’ve done wall features and sold a lot of paper to a lot of people all over the world really.

Along with the small size of the domestic market, some ecopreneurs believed that New Zealanders were not as ready to adopt their green products as consumers in some overseas countries (particularly the UK and the USA). For example, one ecopreneur believed that in New Zealand market “people are so short sighted and stupid”. In this example, the ecopreneur sold products to the world. She explains further:

So there’s dribs and drabs go out within New Zealand but probably no more than 40 tons a year. The rest is all exported.…It’s a barrier to being an exporter, which is the ‘-preneur’ part of it. I mean it’s hard to be an ecopreneur in New Zealand in the current financial climate.

Conclusion

Contributions to both the ecopreneurship and SCM literatures are now made, which add new data from this group of ecopreneurs. Table 3 shows the similarities and differences between the extant SCM literature and the results of the current study, and these results are discussed next. In addition, a number of research propositions are detailed to help to advance the field of ecopreneurship, which we argue is going to grow in significance as environmental awareness increases.

Supply side decisions

The supply side conclusions we find are as follows:

-

1.

Ecopreneurs consider the effects of importing in terms of environmental costs.

-

2.

They assess the environmental record of suppliers as well as the countries they are procuring from.

These assessments that ecopreneurs make are similar to those found in a study of textile companies (Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004). The ecopreneurs in our study felt it important to consider their suppliers’ environmental products, practices and processes and were not driven to do so by external influences. This contrasts with the prior research which suggests that many stakeholders are now expecting companies to be responsible for their suppliers’ environmental management (Christmann and Taylor 2002). Additionally, these ecopreneurs were often concerned with particularly countries’ reputations as being environmentally friendly or not. It would appear that there may be a continuum of acceptability of environmental costs of importing and manufacturing offshore. Further questioning on ecopreneurs’ stances on importing and manufacturing would be beneficial. For example, if production (or supplies) was unavailable in New Zealand, would ecopreneurs’ green values hold firm enough to stop them selling an offshore-produced product?

-

3.

They assess the social aspects of manufacturing processes in other countries (e.g. child labour).

Ecopreneurs’ environmental concerns about other countries extended to social aspects of production processes such as the types of labour and working conditions. This was particularly interesting given that our definition did not require ecopreneurs to be socially motivated as other studies have proposed (Dixon and Clifford 2007). Given that our definition of ecopreneurs is for-profit businesses (which sell green products and services) that are started with strong green values, this is an interesting finding. Whilst tentative, we believe that green values cannot be easily distinguished from social values in ecopreneurs, and the significance and effect of this requires further research.

The size and importance of the company as a customer was found in prior studies of suppliers’ desire to adopt environmental practices (Forman and Søgaard Jørgensen 2004). We concur with this finding and believe that these ecopreneurs had little power to influence their suppliers’ practices other than to take their business elsewhere. Further testing on larger samples of ecopreneurs (operating larger companies) to assess their strength in making environmental demands on their suppliers would be helpful. In some cases, it was noted that this was difficult, particularly if the ecopreneur wanted to buy New Zealand-made supplies or manufacture locally. This leads to our fourth conclusion:

-

4.

Ecopreneurs want to manufacture in New Zealand regardless of cost.

The ecopreneurs in this study primarily wanted to manufacture their goods locally. Their green values influenced this decision, and this contrasts with prior research which has found that some companies see environmentally based manufacturing as a strategic opportunity (Crowe and Brennan 2005). Manufacturing locally (or regionally such as in Australia) can reduce transport costs for New Zealand companies (Chetty and Campbell-Hunt 2003). Questions which arose earlier around the strength of ecopreneurs’ commitment to manufacture locally would be more clearly interpreted if they had a greater understanding of consumer behaviours. For example, how much weight do consumers place on buying locally made products? Are consumers prepared to pay what is potentially an additional premium for New Zealand (locally) made products? This is important because often, eco-friendly products are more expensive, and green marketing research has shown that environmentally conscious consumers are also relatively price-sensitive (Shrum et al. 1995).

Demand side decisions

On the demand side of the business, more environmental issues emerged which affected internationalisation decisions. Two conclusions are presented:

-

5.

Ecopreneurs consider the effects of their exporting in terms of environmental costs (e.g. transport and carbon emissions).

Much of the literature focuses on barriers to exporting, and transport costs rank relatively highly across the research (Leonidou 2004). Other small firm research found resource limitations to be barriers (Fillis 2004). It is our view that it is not necessarily these commonly found barriers which stop ecopreneurs exporting, but it is their environmental values. These ecopreneurs are concerned with the complete environmental impact of exporting. This led to their preference for selling locally.

-

6.

Ecopreneurs are concerned with selling locally (New Zealand-wide and some were even regionally based).

In this study, we did not find evidence of anything other than their green values in stopping participants from exporting. We do not believe that these are ‘barriers’ as such and that selling locally is not a failure from ecopreneurs’ viewpoints. This is in contrast to researchers who suggest that policymakers should help companies overcome barriers to their exporting (Leonidou 2004). We do not suggest that the ecopreneurs override or compromise their green values for the sake of exporting. We contend that ecopreneurs question the commonly held views of policy makers and practitioners (e.g. venture capitalists and bankers) on issues such as internationalisation and growth. Ecopreneurs may indeed represent a potentially new paradigm for doing business that does not follow the traditional exporting route, and a greater understanding of ecopreneurs’ rationale for remaining local is required via further research.

In summary, our findings corroborate the large body of evidence which suggests that the entrepreneur’s vision, characteristics and personality play an important role in internationalisation decisions (Crick et al. 2006; Hutchinson et al. 2007). It would appear from our exploratory study that these decisions may well extend to SCM decisions. We find a number of interesting green values and oftentimes dilemmas that ecopreneurs face when dealing with SCM issues. We see parallels with research on craft entrepreneurs who, in many cases, are more concerned with their lifestyle and the art of their work than they are with market forces (Fillis 2004). Whilst we do not present a list of research questions that could be considered by future researchers, we believe that more general understanding of ecopreneurs rationales, decisions and values needs to be undertaken before we can delve deeply into the specifics of ecopreneurs and internationalisation. Therefore, we recommend that further exploratory research is conducted using larger samples and progress to using more quantitative approaches in order to be able to generalise further.

Generalisability and limitations of the research

Our final comment regards the applicability of this study to other contexts—particularly to other country contexts and other ecopreneurs. As noted, New Zealand may offer a relatively unique setting in terms of its size, geographic isolation and clean, green image. However, we believe that the country context may play a relatively small role in the findings as it appears that the internationalisation decision is one that ecopreneurs make almost entirely based on their green values. This supports research on entrepreneurs generally, which found personal characteristics to be important to internationalisation decisions (Hutchinson et al. 2007). We conclude that the dilemmas facing these New Zealand ecopreneurs may offer a glimpse into future realities for businesses in other countries. Environmental issues are likely to become more mainstream as environmental management becomes increasingly regulated, there is more demand from consumers and resource scarcity becomes more frequent. More environmentally friendly transport options may also have to be considered as commodities such as oil become increasingly expensive. Whilst it is beyond the scope of this exploratory research, our findings open up the emerging dialogue that ecopreneurship may represent a new business paradigm. Thus, our view is that they may represent a shifting paradigm in terms of the way businesses operate. Further work around the findings that have emerged from our study will shed more light on these propositions.

There are undoubtedly limitations to this study. The most apparent is the small number of case studies, although as noted in “Methods”, this is due to the limited understanding of ecopreneurs and the need for initial qualitative research to develop further research propositions. However, the findings of this study open the dialogue on how ecopreneurs view internationalisation with respect to SCM, and we encourage further research and testing on a broader scale of the conclusions presented here.

References

Anderson AR (1998) Cultivating the Garden of Eden: environmental entrepreneuring. J Org Change Manag 11(2):135–144

Bacharach SB (1989) Organizational theories: some criteria for evaluation. Acad Manag Rev 14(4):496–515

Bansal P, Roth K (2000) Why companies go green: a model of ecological responsiveness. Acad Manage J 43(4):717–736

Carter CR, Ellram LM, Ready KJ (1998) Environmental purchasing: benchmarking our German counterparts. Int J Purch Mater Manage 34(4):28–38

Chetty S, Hamilton RT (1993) The export performance of smaller firms: a multi-case study approach. J Strat Mark 1(4):247–256

Chetty S, Blankenburg Holm D (2000) Internationalisation of small to medium-sized manufacturing firms: a network approach. Int Bus Rev 9:77–93

Chetty S, Campbell-Hunt C (2003) Paths to internationalisation among small-to medium-sized firms: a global versus regional approach. Eur J Mark 37(5/6):796–820

Christmann P, Taylor G (2002) Globalization and the environment: strategies for international voluntary environmental initiatives. Acad Manage Exec 16(3):121–135

Clemens B (2006) Economic incentives and small firms: does it pay to be green? J Bus Res 59(4):492–500

Cohen B, Winn M (2007) Market imperfections, opportunity and sustainable entrepreneurship. J Bus Venturing 22(1):29–49

Corbett LM, Campbell-Hunt C (2002) Grappling with a gusher! manufacturing’s response to business success in small and medium enterprises. J Oper Manag 20(5):495–507

Coté R, Lopez J, Marche S, Perron G, Wright R (2008) Influences, practices and opportunities for environmental supply chain management in Nova Scotia SMEs. J Clean Prod 16:1561–1570

Crick D, Bradshaw R, Chaudhry S (2006) “Successful” internationalising UK family and non-family-owned firms: a comparative study. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 13(4):498–512

Crowe D, Brennan L (2005) Environmental considerations within manufacturing strategy: an international study. Bus Strategy Environ 16:266–289

de Bruin A, Lewis K (2005) Green entrepreneurship in New Zealand: a micro-enterprise focus. In: Schaper M (ed) Green entrepreneurship in New Zealand: a micro-enterprise focus. Ashgate, Aldershot

Dean TJ, McMullen J (2007) Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: reducing environmental degradation through environmental action. J Bus Venturing 22(1):50–76

Dixon S, Clifford A (2007) Ecopreneurship—a new approach to managing the triple bottom line. J Org Change Manag 20(3):326–345

Edmondson A, McManus S (2007) Methodological fit in management field research. Acad Manag Rev 32(4):1155–1179

Eiadat Y, Kelly A, Roche F, Eyadat H (2008) Green and competitive? An empirical test of the mediating role of environmental innovation strategy. J World Bus 43(2):131–145

Eisenhardt KM (1989) Building theories from case study research. Acad Manag Rev 14(4):532–550

Fillis I (2004) The internationalizing smaller craft firm. Int Small Bus J 22(1):57–82

Forman M, Søgaard Jørgensen M (2004) Organising environmental supply chain management. Green Manag Int 45:43–62

Frederick H, Chittock G (2006) Global entrepreneurship monitor Aotearoa New Zealand: 2005 executive report. Unitec, Auckland

Freimann J, Marxen S, Schick H (2005) Sustainability in the start-up process. In: Schaper M (ed) Sustainability in the start-up process. Ashgate, Aldershot

Gibbs D (2007) The role of ecopreneurs in developing a sustainable economy, corporate responsibility research conference. University of Leeds, UK

Glaser BG (1992) Basics of grounded theory analysis: emergence vs forcing. Sociology Press, Mill Valley

Hutchinson J, Alexander N, Quinn B, Doherty A (2007) Internationalization motives and facilitating factors: qualitative evidence from smaller specialist retailers. J Int Mark 15(3):96–122

Issak R (2002) The making of the ecopreneur. Green Manag Int 38:81–91

Jones MV, Coviello NE (2005) Internationalisation: conceptualising an entrepreneurial process of behaviour in time. J Int Bus Stud 36:284–303

Keogh P, Polonsky M (1998) Environmental commitment: a basis for environmental entrepreneurship? J Org Change Manag 11(1):38–49

Kuivalainen O, Sundqvist S, Servais P (2007) Firms’ degree of born-globalness, international entrepreneurial orientation and export performance. J World Bus 42(3):253–267

Laroche M, Bergeron J, Barbaro-Folero G (2001) Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J Consum Mark 18(6):503–520

Leonidou L (2004) An analysis of the barriers hindering small business export development. J Small Bus Manage 42(3):279–302

Manolova TS, Brush CG, Edelman LF, Greene PG (2002) Internationalization of small firms: personal factors revisited. Int Small Bus J 20(9):9–31

Miles M, Covin J (2000) Environmental marketing: a source of reputational, competitive, and financial advantage. J Bus Ethics 23(3):299–311

Min H, Galle WP (1997) Green purchasing strategies: trends and implications. Int J Purch Mater Manage 33(3):10–17

Ministry of Economic Development (2007) SME’s in New Zealand: structure and dynamics. Wellington Ministry of Economic Development

Montabon F, Melnyk SA, Sroufe R, Calantone RJ (2000) ISO 14000: assessing its perceived impact on corporate performance. J Supply Chain Manag 36(2):4–16

O’Brien C (2002) Global manufacturing and the sustainable economy. Int J Prod Res 40(15):3367–3877

Pastakia A (1998) Grassroots ecopreneurs: change agents for a sustainable society. J Org Change Manag 11(2):157–173

Peattie K (2001) Golden goose or wild goose? The hunt for the green consumer. Bus Strategy Environ 10:187–199

Post J, Altman B (1994) Managing the environmental change process: barriers and opportunities. J Org Change Manag 7(4):64–81

Prakash A (2002) Green marketing, public policy and managerial strategies. Bus Strategy Environ 11(5):285–297

Ramus C (2002) Encouraging innovative environmental actions: what companies and managers must do. J World Bus 37(2):151–164

Schaltegger S (2002) A framework for ecopreneurship: leading bioneers and environmental managers to ecopreneurship. Green Manag Int 38:45–58

Schaper M (2002) The essence of ecopreneurship. Green Manag Int 38:26–30

Shrum L, McCarty J, Lowrey T (1995) Buyer characteristics of the green consumer and their implications for advertising strategy. J Advert 24(2):71–82

Simpson D, Samson D (2008) Developing strategies for green supply chain management. Decis Line 39(4):12–15

Straughan R, Roberts J (1999) Environmental segmentation alternatives: a look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium. J Consum Mark 16(6):558–575

Strauss A, Corbin J (1990) Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage, Newbury Park

Walley E, Taylor D (2002) Opportunists, champions, mavericks…? A typology of green entrepreneurs. Green Manag Int 38:31–43

Walton SV, Handfield RB, Melnyk SA (1998) The green supply chain: integrating suppliers into environmental management processes. Int J Purch Mater Manage 34(2):2–17

Webb DJ, Mohr LA, Harris KE (2008) A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J Bus Res 61(2):91–98

Whetten DA (1989) What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Acad Manag Rev 14(4):490–495

Wycherley I (1999) Greening supply chains: the case of The Body Shop International. Bus Strategy Environ 8:120–127

Yin RK (1984) Case study research: design and methods. Sage, Beverly Hills

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kirkwood, J., Walton, S. How ecopreneurs’ green values affect their international engagement in supply chain management. J Int Entrep 8, 200–217 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-010-0056-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-010-0056-8