Abstract

Do fundamental index funds beat traditional ones? The major companies that offer the new fundamentally indexed international mutual funds are Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA), Research Affiliates, and WisdomTree. A major provider of traditional international index funds is DFA. We compare various fundamental international index fund portfolios from these providers with individualized benchmark portfolios composed of DFA traditional international funds. For each family we provide 16 measures of how much an aggregate of its fundamental indexes outreturned its corresponding DFA traditional benchmark portfolio through June 2014. Taking averages, (1) the Research Affiliates PowerShare aggregate out-returned its corresponding DFA traditional benchmark portfolio by 1.08 %/year, (2) the DFA fundamental aggregate under-returned by 0.30 %/year, and (3) the WisdomTree aggregate under-returned by 0.74 %/year. One cheer for fundamental international indexation and two for traditional indexation.

Edward Tower is a Professor of Economics at Duke University and a long-term visiting professor at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok Thailand.

Heehyun Lim is a Phd Candidate and Teaching Fellow at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL classification

The fundamental index fund is a hybrid of active and passive management. Fundamental indexation is passive in that it uses rules for portfolio selection. It is active in the sense that its portfolio weights deviate from market cap weights, and therefore fundamental indexation takes an active position relative to the cap-weighted market.

Do fundamental index funds beat traditional ones? The major companies that offer the new fundamental index international mutual funds are Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA), Research Affiliates, and WisdomTree. A major provider of traditional international index funds is DFA. We compare various fundamental index fund portfolios from these companies with individualized benchmark portfolios composed of DFA traditional funds.

Jeremy Siegel said in an interview with the New York Times in 2006, traditional index funds overweight overvalued stocks while they underweight undervalued stocks, causing investors to buy fashionable assets at high prices (Anderson, 2006). Robert Arnott, Chairman of Research Affiliates, succinctly describes fundamental indexation (PowerShares, 2012 p. 3): “Fundamental Index strategies use Fundamentals, various measures of firm size, including dividends, earnings, cash flow, sales, book-equity values, and so on.” For more complete descriptions of active and fundamental index strategies see Arnott and Fabozzi (1992) and Arnott et al. (2008).

The opponents of fundamental index funds, however, claim that the excess return generated from fundamental indexation is minor and that the additional costs, including turnover costs, and tax inefficiencies, cancel out the advantage of this alternative index fund, if there is any.

Tower and Yang (2013) compare DFA, Research Affiliates, and WisdomTree US fundamental index funds with portfolios constructed out of Vanguard index funds. Here, by examining international funds we complete the inquiry that Tower & Yang initiated.

We use a modified “style analysis” of Sharpe (1992) to compare the performance of traditional index funds and fundamental index funds of international stocks. Vanguard has a limited range of international index funds, so instead of using Vanguard traditional index funds to benchmark, here we employ DFA traditional index funds to do the job.

Tower and Yang (2013) compare Vanguard, a traditional index fund manager, with leading fundamental index fund families, DFA-Core and Vector funds, Power shares-Research Affiliates (RAFI for short), and WisdomTree. They use two Fama-French models as well as Sharpe’s style analysis (Sharpe 1992). They find that the RAFI funds and WisdomTree funds outreturned their Vanguard clones, whereas DFA core slightly underreturned. Instead of supporting either fundamental or traditional funds, their study produces the conflicted result: “two cheers for enhanced [or more properly fundamental] indexation and one for traditional.” Their results for the Fama-French models and the Sharpe style analysis models were quite similar. So here we simplify matters by using only the Sharpe (1992) style analysis.

To clarify terminology, one set of readers (identified in the acknowledgements) wrote, “Enhanced index funds are the standard term used in the finance industry to denote funds which manage off a given benchmark index, usually with an implicit or explicit tracking error constraint. RAFI and WT index funds do not fall into this category. We would suggest using the term ‘smart beta,’ ‘alternative index’ or ‘strategic index,’ instead.” There are advocates for all three. We choose the term “fundamental index funds.”

15.1 Style Analysis

Sharpe (1992) introduces a useful way of comparing fund performance. He constructs a clone portfolio of indexes that minimizes the variance of the difference between the return on the fund and the synthetic portfolio. The clone portfolio is a combination of indexes that reflects the manager’s asset mix. For example, if a manager maintains a portfolio consisting of 25 % small value stocks and 75 % large growth stocks, running a regression of the return of the mutual fund on the returns of a set of indexes, not suppressing the constant term, and constraining the sum of the portfolio weights, represented by the regression coefficients, to add up to 1, should yield a coefficient of 0.25 for the small value index and 0.75 for the large growth index. Lucas and Riepe (1966) also provide a transparent discussion of returns-based style analysis.

We use a modified version of style analysis as Tower (2009) more comprehensively explains, replacing indices with index funds. Using 11 DFA international traditional index funds, we create the clone portfolio as that which best mimics the pattern of returns of each individual international fundamental fund or portfolio of fundamental funds, henceforth, simply fundamental fund.

15.2 How Do We Create the Clone Portfolio?

We instruct Microsoft Excel Solver to find the weighted sum of each traditional fund’s return to produce the fundamental fund’s return. By allowing the weights, which must sum up to 1, to vary, we can find the particular set of weights that minimizes the standard deviation of return differentials between the fund and its clone portfolio. In short, solver finds the set of coefficients that minimizes the variance of the return differentials between the fundamental fund and the traditional fund portfolio. Thus we regress the return of the fundamental fund on the returns of the traditional funds, while constraining the portfolio weights to sum to 1. We assume that the managers of the fundamental index fund portfolio and the clone portfolio rebalance once each month in order to maintain the portfolio weights.

15.3 Why Use a Clone Portfolio and Style Analysis?

We compare each fundamental fund portfolio with the collection of DFA traditional funds which tracks it best. The geometric average excess return of the fundamental fund, continuously compounded, is α. It represents how much value has been added by fundamental indexation.

Our readers noted “Since the clone portfolio uses traditional indexes that vary across regions (like Asia, Europe, Japan, developed and emerging markets, etc.) and across sizes (small cap, large cap) and styles (value and growth), measuring an index against its clone will remove all outperformance or underperformance due to region, size and style. The remaining alpha, therefore is the “skill” that must be due to something other than picking the right region, size or style.”

“It is important to note that the clone portfolios are created ex post. So even if a manager has tremendous foresight and can pick the region/size/style combination that will perform the best over the sample period, he is evaluated relative to a clone portfolio that has the benefit of picking that region/size/style after the fact. … [Thus we] “are looking for skill that goes beyond this, such as picking stocks within these buckets or dynamically shifting allocation among these buckets in a way that generates alpha.”

15.4 Why Use Continuous Compounding and Geometric Average Return?

In order to measure the average rate of return over multiple time periods, we employ continuously compounded geometric average return. A portfolio that returns 50 % 1 year and −50 % the next year does not have an average return of zero % per year. But a portfolio that returns a continuously compounded 50 % in 1 year and −50 % in the next year does have a geometric average return of 0 % over the 2 years. Thus, the geometric average return over a span is the average of the geometric average returns over the periods that comprise the span.

15.5 Why Use Equally Weighted Portfolios and Risk-Averse Portfolios?

To compare the performance of traditional indexation and fundamental indexation, we consider two types of portfolio composed of fundamental index funds from each fund family. This approach is more relevant than looking at individual funds, because typical investors hold a variety of funds. Thus, in addition to looking at each fund separately, we create an equally weighted portfolio and a risk-averse portfolio to compare the returns with a traditional clone portfolio. While the equally weighted portfolio is not necessarily optimal, it is by far the simplest way to look at the overall performance of the assets in a fund family.

The risk-averse portfolio, however, is perhaps more useful, especially when we account for the investment atmosphere after the financial crisis, with the obvious need to make safe decisions, and we recognize that some funds, such as WisdomTree’s India Earnings Fund, are highly specialized and would constitute a small proportion of a diversified portfolio. Therefore, in order to reflect the preference for less risk, we create a risk-averse portfolio of each fund family. The weights of each risk-averse fundamental index fund portfolio were determined to minimize the standard deviation of the return of the portfolio, again using Microsoft Excel Solver.

15.6 Why Do Some of Our Portfolios Allow Short Selling?

The Sharpe style analysis constrains the portfolio weights to be nonnegative. In other words, it does not allow holding short positions in any fund to create a clone portfolio. However, when an investor who initially held traditional funds buys a fundamental fund, in some cases, he needs to increase his holdings of some traditional funds to imitate his previous style.

For example, suppose the fundamental fund is more focused on growth companies than any of the DFA traditional funds. Our investor has an initial portfolio of DFA traditional funds. She invests a dollar in the fundamental fund. She maintains her style by selling two dollars of her DFA traditional blend fund and buying one dollar worth of the DFA traditional value fund. Then the clone portfolio is 200 % DFA traditional blend and −100 % DFA traditional value. Regressing the fundamental fund return on the traditional fund returns, while constraining the coefficients to sum to one and not repressing the constant term, would yield a coefficient of 2 for the DFA traditional blend fund and −1 for the DFA traditional value fund.

Therefore, a negative coefficient for a particular fund in the clone portfolio signals that the funds with positive coefficients in the clone portfolio are leveraged in order to achieve the same style as before, and the investor buys more of the traditional fund with the negative coefficient to maintain portfolio balance when she buys the fundamental fund. The coefficients show the net sales of each traditional fund necessary to maintain style when a dollar’s worth of the traditional fund is purchased. While traditional index funds cannot be sold short, ETFs can be sold short, and some ETFs mimic traditional index funds.

15.7 Data

The ideal pick of funds is mutually exclusive but exhaustive (Sharpe, 1992). The data were selected to conform as much as possible to these criteria by eliminating the funds with redundant components. For example we only use one of the DFA International Value funds. The data on monthly returns were collected from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP), and some missing data were filled from Yahoo Finance and Morningstar. In this study, the portfolios of fundamental DFA funds have monthly returns spanning from between May 2005 and September 2008 to June 2014, those for RAFI span from between July 2007 and October 2007 to June 2014, and those for WisdomTree span from between July 2006 and December 2009 to June 2014. We examined all the fundamental international stock mutual funds from the three fund families that existed during our time frame except for sector funds.

15.8 The Exhibits

To construct the clone portfolios, we use 11 DFA traditional index funds. They are listed alphabetically by ticker next to the bottoms of Exhibits 15.1, 15.2, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5, and 15.6. In all the Exhibits,

-

α is the annual average continuously compounded excess return of the fundamental portfolio over that of the traditional index clone over the entire period, continuously compounded, and expressed in percentage points per year.

-

Significance of α. In all of our exhibits “significance” is the significance of α on a one tail test. It denotes the probability that the sign of α for our sample is different from the sign of the α for the universe from which the sample is drawn. For example, from the top line of Exhibit 15.1. the DFA fund with ticker DFCCX outreturned its clone traditional portfolio with no shorts permitted by α equal to 0.14 % per year, continuously compounded, and the significance of 33 % tells that the probability is 33 % that α for the universe is negative rather than positive. The statistical significance test is done using the Paired 2-Sample t-Test from the Microsoft Excel Data Analysis Package, using continuously compounded monthly returns.

-

Correlation is the correlation of the continuously compounded monthly returns for the fundamental fund and its clone.

-

Excess standard deviation of fund is the excess volatility of the fundamental portfolio compared to that of the traditional portfolio.

-

Standard deviation of prediction error measures the standard deviation of the return differentials, not continuously compounded. During modeling, we constrained this value to be minimized through Solver.

-

The numbers near the bottom boxes are the weights in percent given to each DFA traditional index fund to make the portfolio that mimics the compared fundamental portfolio. In every column, they add up to 100.

-

Sum of shorts is the share of the mimic portfolio that is held short, expressed as a percent. It is zero when shorts are prohibited.

-

α 1st half and α 2 nd half are the αs for the two half periods, and α average is the average of these two αs. Dividing the period allows closer tracking of the style changes.

15.9 DFA Individual Funds

We use both traditional index funds and fundamental index funds from Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA). The DFA traditional index funds constitute the clone portfolio to compare with fundamental funds. The overall investment strategy of DFA on international investment can be found at the DFA homepage (2014). More details of each fund are described in DFA’s most recent prospectus (2014).

DFA’s fundamental index funds are called DFA core and DFA vector funds. The weights of stocks in their portfolios are determined by fundamentals and market capitalization. Among fundamentals, growth and value are assessed by factors, such as price-to-cash flow or price-to-earnings ratios (DFA Prospectus (2014)). Six DFA fundamental index funds were selected. They are listed, proceeded by their tickers, in Exhibit 15.1. for long positions only in the clone portfolios and Exhibit 15.2. for shorts permitted.

DFA funds can only be purchased through an adviser, who charges a fee. For a list of advisors see the Retire Early Home Page (2007). Drawing from that page, for example, Asset Builder (2013) charges 0.45 % of assets annually for portfolios between $50 thousand and $250 thousand dollars and 0.30 % of assets for portfolios between $1 million and $4 million. In addition there are custodial and transactions fees. Thus, since we are using DFA traditional funds as benchmarks, these fees increase the attractiveness of RAFI and WisdomTree, beyond those presented here.

15.10 RAFI Individual Funds

RAFI funds are the PowerShares FTSE RAFI portfolios. These portfolios incorporate four fundamental factors—dividends, cash flow, sales, and book equity value—to determine each fund’s weights. We examine four RAFI fundamental index funds. They are presented in Exhibits 15.3 and 15.4.

The major outlier with a low correlation and a no-shorts α of 2.87 %/year is PAF (FTSE RAFI Asia Pacific ex-Japan. In November 2011 it invested 42.1 % of its assets in Australia and 36.2 % in the Republic of Korea. In April 2014 its top ten holdings were also from those two countries. There were no comparable DFA traditional index funds, so the huge α averages of close to 4 %/year may reflect the outperformance of the average stocks in those countries rather than better than average stock selection from those two countries. The RAFI funds are described in Powershares (2014) and ResearchAffiliates (2014).

15.11 WisdomTree Individual Funds

As described on its website, WisdomTree considers fundamentals such as dividends and earnings to reflect a company’s appeal (WisdomTree (2014)). So the funds focus either on dividends or earnings. Seventeen fundamental index funds were selected from WisdomTree. They are presented in Exhibits 15.5 and 15.6.

15.12 The Individual Fundamental Index Funds

For the individual funds 17/24ths (71 %) of the DFA αs are negative, 12/16ths (75 %) of the RAFI αs are positive and 44/68ths (65 %) of the WT αs are negative. The average individual-fund αs have the same sign pattern.

Thus, focusing on average and median αs, DFA and WisdomTree fundamental index funds had lower returns and RAFI fundamental funds had higher returns than DFA’s corresponding traditional index fund portfolios. The weak significance levels mean that these calculations provide some but not a lot of guidance for what to expect from these families in the future.

15.13 Fundamental Index Portfolios

Exhibits 15.1, 15.2, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5, and 15.6 also describe the simulations for equally weighted portfolios, and for the portfolios with minimum risk. Minimum risk is minimum standard deviation of return over the sample period. Portfolio weights are constant. Both the fundamental and the clone portfolios are rebalanced monthly. The minimum risk portfolios are

-

For DFA 100 % in the International Sustainability Core I fund.

-

For RAFI 94.3 % in the FTSE RAFI Developed Market ex-US Small-Mid fund and 5.7 % in the FTSE RAFI Developed Markets ex-US fund.

-

For WisdomTree we constrained the maximum value of the portfolio in Japanese equities to be 25 %. The constrained risk-averse portfolio is 75 % in the Global ex-US Growth fund and 25 % in the Japan SmallCap Dividend fund.

15.14 DFA Aggregates

Calculations for the aggregates are in the right four columns in Exhibits 15.1, 15.2, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5, and 15.6. For each fund family, they consist of the calculations for the two portfolios and the average and median values for individual funds.

Although August 2008 marks the latest inception of a DFA fundamental index fund, the data was obtainable only from September 2008. We use monthly returns data, which are calculated at the end of each month. For the DFA equally weighted fundamental index portfolio we have observations: from September 2008 to June 2014, and for the risk-averse portfolio we have observations from April 2008 to June 2014.

From Exhibits 15.1 and 15.2, 14 of the 16 aggregate DFA αs are negative. Our benchmark is traditional funds issued by the same company, so the smallness of these numbers for the equally weighted portfolio is not surprising, nor is the weak significance. The large negative αs for the risk adverse portfolio are a surprise.

Minimum, median, average and maximum values for the 16 portfolio alphas are reported in Exhibit 15.7. For DFA the average of the aggregate αs is −0.33 %/year. Our take-away is that the DFA fundamental funds offer similar returns to the traditional DFA funds. This is also reflected in the very high correlations of returns: all over 99.9 %. The poor level of significance means that we cannot say with any confidence that the fundamental funds are inferior to traditional funds, but we can say that no evidence is offered for the superiority of DFA’s fundamental funds over DFA’s traditional index funds. The DFA simulations show that an investor who is meticulous about rebalancing would have done slightly better (aside from rebalancing costs) by holding traditional funds.

For the equal weight no-short fundamental portfolio, the expense ratio in 2010 is 0.04 % higher than for its clone portfolio, and the α is a comparable −0.06 %.

15.15 RAFI Aggregates

The evaluation of RAFI portfolios starts from October 2007, when all the RAFI fundamental funds were active and like the others carries through June 2014.

From Exhibits 15.3, 15.4, and 15.7 all of the aggregate RAFI αs are positive, ranging from 0.04 %/year to +2.65 % per year with median and average values of 0.92 %/year and 1.08 % per year respectively. The correlations for all the aggregates are all at least 96.8 %. The average excess standard deviation of return is slightly negative. Thus, the RAFI funds provided excess returns with slightly lower risk than their traditional DFA clones.

15.16 WisdomTree Aggregates

The evaluation of WisdomTree equal-weight portfolio starts from March 2008, when all the WisdomTree fundamental funds were active, except HEDJ and GULF which we excluded from the equal-weight portfolios and possible risk-averse portfolios.

From Exhibits 15.5, 15.6 and 15.7, 14/16ths of the WisdomTree aggregate αs are negative, ranging from −2.60 %/year to 1.34 %/year with median and average values of −0.86 %/year and −0.74 %/year respectively. All of the correlations for the aggregates are at least 81.9 %. Six out of eight of the excess standard deviations of the aggregates are positive, with an average value of 0.019 %/month.

15.17 Does the First Half Period α Predict the Second Half Period α?

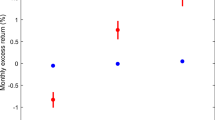

Does the α for a fundamental mutual fund in the first half of the period predict the α for the second period? Each fund family has four aggregates. This gives us eight first half αs and eight second half αs per family. We take averages for the first and second halves of the period: α 1 and α 2 . These are graphed in Exhibit 15.8. The graph shows that the regression indicates a one percentage point increase in the first period α predicts a 0.57 percentage point increase in the second period α. The R2 for the relationship is 0.93. Thus for this particular data set the relationship between the αs is positive, but the variance in the second period is smaller than that in the first period.

Our readers note the much smaller range for alphas in the second period than in the first. They write “Our guess would be that this is because the global financial crisis is in the first half of the sample, and the second half is much less turbulent by comparison. If that is the reason for the change in dispersion of alpha from the first half of the sample to the second half, then that would explain the low slope.”

15.18 Are the αS Explained by Different Sector Returns?

Bill Bernstein suggested that some of our αs might be explained by the different sectors that different funds invest in. For example, the WT equally weighted portfolio invested roughly 5 % more of its portfolio over the period in financial services and roughly 5 % less in technology than did its DFA clone (shorts permitted).

From the January 2012 Morningstar Principia disk, we drew data on the average share of investment in 11 sectors for the RAFI and WT equally weighted portfolios and their DFA clones. For convenience, we used the 3-year average ending in September 30, 2011, rather than the precise average over the entire period. We calculated the fundamental fund share in each sector minus that for the DFA clone: call it the share difference. Fidelity has sector funds that correspond to each of the 11 sectors. They are labeled Fidelity Select funds. We used Yahoo finance to gather the geometric average, continuously compounded rate of return for each Fidelity fund over the life of the equally weighted portfolio: call it return. We assumed that these Fidelity returns are good proxies for the returns to the corresponding sectors worldwide. We multiplied share difference by return for each sector and summed over the entire 11 sectors to get: the part of α that is explained by share difference: call it αShare.

The α for the equally weighted WT portfolio versus the short DFA clone through December 2012 is minus 2.15 %/year. The corresponding αShare is minus 1.22 %/year. Thus over half of the α is explained by sector choice.

The α for the equally weighted WT portfolio versus the long DFA clone, also ending in December 2012, is minus 1.35 %/year. The corresponding αShare is minus 0.40 %/year. Thus 30 % of the α is explained by sector choice.

For the RAFI equal-weight portfolio compared with the no-shorts clone the α calculated through December 2012 is +0.91 %/year. The αShare is +0.075/year. Thus less than 10 % of its α is explained by sectoral choice.

The Fidelity Select funds are primarily composed of US stocks, so they are not a great proxy for the performance of the international sectors, so it is likely that we have under-estimated the impacts of sectoral differences in our clone portfolios.

15.19 Conclusion

We have analyzed portfolio returns for the international fundamental index funds from DFA, RAFI, and WisdomTree, relative to the corresponding traditional index funds from DFA. These average αs for the 16 calculations for the four aggregates for each of the three fund families are −0.33, 1.08, and −0.74 % per year. The corresponding average significance levels on a one tailed test are 20, 35, and 25 %. Thus DFA slightly under-returned, RAFI out-returned, and WT under-returned, but the αs are not significant at standard levels.

The average standard deviations of the returns of each of the aggregates for the fundamental index funds for DFA and WisdomTree were higher than the clone portfolios (both by 0.019 %/month), but for RAFI it was lower (−0.040 %/month). In the Tower Yang (2013) paper the corresponding averages were all higher.

The corresponding average αs for US fundamental index fund portfolios relative to Vanguard US index funds from Tower and Yang (2013) are −1.43, +2.57, and 2.21 %/year. Thus both domestic and international DFA under-returned, while both domestic and international RAFI out-returned. The WisdomTree US portfolio out-returned but the WisdomTree international aggregates under-returned. Putting the conclusions of both studies together: three cheers for fundamental indexation and three cheers for traditional indexation. Thus on average, based on these calculations, we cannot rank the two methods of indexing.

These calculations are for short periods, so we hesitate to make too much of them. Still, we do not know a better way to form priors for what future excess returns of fundamental index funds are likely to be. We hope others using additional data and alternative approaches will shine a brighter light on the question.

Research Affiliates is a definite winner from this study. This rash conclusion, however, should be tested further with longer time span in the future. The study presented in the chapter, with its mixed results, can be summarized by the same quotation from Bernstein (2006) with which Tower and Yang concluded their study: “The prospective shareholder needs to consider not only the selection paradigm used, but just who is executing it.”

References

Arnott, R. D., Hsu, J. C., & West, J. M. (2008). The fundamental index: A better way to invest. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Arnott, R. D., & Fabozzi, F. J. (1992). Active Asset Allocation: State of the Art Portfolio Policies, Strategies, and Tactics. New York City, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Asset Builder (2013). Assetbuilder Fees. Retrieved September 14, 2014 from http://assetbuilder.com/investing/assetbuilder_fees

Anderson Jenny. (August 15, 2006). Real Money Rides on Bet on Basics of Investing. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/15/business/15place.html?ex=1313294400&en=d43f3343f3a02979&ei=5090&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss

Bernstein, W. J. (2006). Fundamental Indexing and the Three-Factor Model. Efficient frontier, http://www.efficientfrontier.com/ef/0adhoc/fi.htm.

DFA. DFA home page Non-US Equity section. http://www.dfaus.com/strategies/non-us-equities.html. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

DFA Prospectus. (February 28, 2014) http://www.dfaus.com/pdf/prospectuses/idg_equity_i_pros.pdf

Lucas, Lori, and Riepe, Mark W. (1966) The Role of Returns-Based Style Analysis: Understanding, Implementing, and Interpreting the Technique. http://corporate.morningstar.com/ib/documents/MethodologyDocuments/IBBAssociates/ReturnsBasedAnalysis.pdf

Powershares. Fundamental Index Methodology. Invesco PowerShares Capital Management LLC. Retrieved September 27, 2014 from http://invescopowershares.com/pdf/P-FUNDAMENTALS-IVG-1.pdf

Research Affiliates. RAFI Fundamental Index. Retrieved September 27, 2014 from http://www.researchaffiliates.com/Our%20Ideas/Solutions/RAFI/RAFI%20Equity/Pages/Home.aspx

Retireearlyhomepage. (2007). Low-cost, fixed-fee DFA investment advisors. Posted July 1, 2007. Retireearlyhomepage.com/dfaadv.html

Sharpe, W. F. (Winter 1992). Asset Allocation: Management Style and Performance Measurement. Journal of Portfolio Management, 18(2), 7–19.

Tower, E. (2009). Classic and enhanced index funds: Performance and Issues. In J. A. Haslem (Ed.), Mutual funds: Portfolio structures, analysis, management, and stewardship (pp. 237–264). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Tower, Edward, and Yang, Chao. (Summer 2013) Is Traditional Indexation Passé? Vanguard versus the enhanced indexers, DFA, RAFI, and WisdomTree. Factor Based Portfolio Construction. Journal of Index Investing, 4(1), 1–12.

WisdomTree. Retrieved September 14, 2014 from http://www.wisdomtree.com/etfs/

Acknowledgments

This chapter is an update and revision of Lim’s honors thesis, which was supervised by Tower. Her thesis is available from her upon request. Bill Bernstein, Henry Blinder, James Dean, John Guerard, Mel Lindauer, and Steve Thorpe provided helpful suggestions. Rob Arnott, Noah Beck, and Vitali Kalesnik kindly commented on a near final version of the chapter. The latter are the readers we have quoted in several instances.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lim, H., Tower, E. (2017). Fundamental Versus Traditional Indexation for International Mutual Funds: Evaluating DFA, WisdomTree, and RAFI PowerShares. In: Guerard, Jr., J. (eds) Portfolio Construction, Measurement, and Efficiency. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33976-4_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33976-4_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-33974-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-33976-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)