Abstract

This essay focuses on risk assessment, a new strategy of risk-based regulation provided by the Fourth Directive on anti-money laundering (AML)/counter terrorism financing (CFT). This strategy is structured on three levels: the supranational/ European Union (EU) level, the national level, and the obliged entities’ level. These levels are linked to and fed by each other in a dynamic way, even though a supremacy role is attributed, to some extent, to the European Commission.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Obliged Entities

- Terrorist Financing

- Risk-based Regulation

- Anti-money Laundering (AML)

- European Securities And Markets Authority (ESMA)

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

5.1 Introduction

The European Union (EU) and the Member States need to identify, understand, manage, and mitigate the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing they face.

Risks are variable in nature and the combination of several variables makes risks increasing or decreasing. In other terms, certain situations present a greater risk of money laundering and terrorist financing, while others might have a less significant impact. It is, therefore, necessary for EU and Member States to underpin a risk-based approach (RBA). Indeed, each measure needs to be assessed also according to a cost-effective approach, since overreaction may waste resources and lead to a lower performance of the whole regulatory framework.1

In this regard, the full and clear knowledge by EU and Member States is necessary to allow them adopting appropriate and proportionate measures to face the risks and avoiding an overreaction. Indeed, economies and crimes change their features so quickly that all institutions struggle to stay ahead. Thus, the need for updated, precise, and accurate information should be at the top of regulators’ list.

The Fourth Directive on money laundering and terrorist financing tries to do so also by entailing a new strategy: the risk assessment. Such strategy should embrace the supranational level (Article 6), the national level (Article 7), and the obliged entities’ level (Article 8). These levels are linked to and fed by each other in a dynamic way, even though a supremacy role is attributed, to some extent, to the European Commission.

5.2 The Reasons for an RBA

Risk-based regulation has been becoming more and more widespread across the world and in different areas such as environment, food, legal service, and finance.2 Risk-based regulation is a set of strategies in the hand of regulators to target public resources at those sites and activities that present threats to regulators’ ability to achieve their objectives.3 By embracing such approach, regulators would tend to focus on the highest risks and they would be encouraged to pull back resources from lower risks. This tendency, however, is not always followed strictly, since lower risks may have some capacity to produce both significant harms and political contention, and consequently regulators may be demanded to face lower risks too.4

With specific regard to anti-money laundering (AML), after the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) issued its Revised Forty Recommendation in 2003, concepts of risk assessment and risk management became two key elements in the definition of the AML regulation.5

In this regard, last FAFT’s Recommendations re-points out that countries should apply an RBA to ensure that measures to prevent or mitigate money laundering and terrorist financing are commensurate with the risks identified. The use of such approach should lead to an efficient allocation of resources across the AML and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) regime.6 More specifically, FAFT’s Recommendations suggest that countries need to: (a) identify higher risks to adequately address them; and (b) allow simplified measures when addressing lower risks. Further, FAFT’s Recommendations point out that countries should have: (a) national AML/CFT policies, informed by the risks identified to be periodically revised; and (b) a coordination mechanism for such policies. This coordination mechanism should concern also the supranational/international level, so that policies and activities to combat money laundering and terrorist financing become more effective.

Against the above background, risk assessment can be regarded as one new strategy of risk-based regulation. Indeed, risk assessment is functional to the use of evidence-based decision-making in order to target the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing. Risk assessment is, therefore, seen as a way to increase effectiveness of AML with the necessary degree of flexibility to allow adaptation to the different situations and actors. In this regard, the IV Directive structures the risk assessment on three levels: EU, national, and obliged entities. However, these levels should not be seen as separate monads, since the Fourth Directive provides for, inter alia, a circular flow of information: top-down (from the Commission to Member States and, finally, the obliged entities) and bottom-up (from the obliged entities to the Member States and, finally, to the Commission). Actually, only a circular flow of information may create a full and clear knowledge of the risk to be faced at and within the EU.

5.3 Risk Assessment at EU Level

The Fourth Directive acknowledges that the importance of a supranational approach to risk identification has been encouraged at international level. In this regard, the Directive indicates the Commission as the best placed authority to review cross-border threats that could affect the internal market and to coordinate the assessment of risks relating to cross-border activities. In order to do so, Member States are required to share the outcomes of their risk assessments with each other and with the EU Institutions, namely the Commission, the European Banking Authority (EBA), the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA), and the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) (jointly referred as European Supervisory Authorities, ESAs).

The flow of information and the findings of the risk assessment at the EU level have to be gathered in a report by the Commission. Such a report is to be prepared by 26 June 2017 and it is to be updated at least every two years, since only updated information may constitute the basis for a real evidence-based decision-making.

More specifically, the said report must cover at least the following issues: (a) the areas of the internal market which are characterised by the highest risks, (b) the risks characterising each relevant sector, and (c) the most widespread means used by criminals to launder their illicit activities.Moreover, with the aim to fruitfully use the flow of information and the different expertise, the Commission has to take into account: (a) the opinions issued by the ESAs (the Joint Committee has to issue its first opinion by 26 December 2016 and renovate it every two years), (b) the Member States’ experts in the areas of AML/CFT, (c) representatives from Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs), and (d) other Union level bodies (where appropriate).

Moreover, the report is to be submitted to the European Parliament and to the Council every two years, or more frequently if appropriate, with the aim to clarify: both (a) the findings resulting from the regular risks assessments, and (b) the actions taken following these findings.

Finally, it seems that the Commission is not only entitled to coordinate risk assessments at and within EU but it is also entitled to “guide” Member States’ risk assessment policies. Indeed, Member States are obliged to base their risk assessments on the Commission’s findings. Moreover, the Commission is entitled to make recommendations to Member States with a comply-or-explain mechanism: if Member States decide not to apply any of the recommendations in their national AML/CFT regimes, they must notify the Commission and provide a justification for such a decision.

5.4 Risk Assessment at National Level

The Fourth Directive requires Member States to take all necessary steps to identify, assess, understand, and mitigate the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing.

More specifically, Member States are required to: (a) designate an authority or establish a coordinating mechanism to address money laundering and financing of terrorism risks (Member States have to notify their designated authority to the Commission, to the ESAs, and to the other Member States); and (b) carry out risk assessments periodically so to keep the relevant information updated.

As already pointed out, the Directive structures the different levels of risks assessments at and within EU as linked to and fed by each other with a guiding role of the Commission. Accordingly, Member States, in carrying out their risk assessments, must make use of the findings of the report by the Commission.

In carrying out the risk assessment, each Member State has to: (a) identify any areas where obliged entities are to apply enhanced measures and, where appropriate, specifying the measures to be taken; and (b) make appropriate information available promptly to obliged entities to facilitate the carrying out of their own money laundering and terrorist financing risk assessments.

According to the Directive, the scope of risk assessment at national level is to: (a) allocate and prioritise the resources to combat money laundering and terrorist financing; and (b) ensure that appropriate rules are drawn up for each sector or area, in accordance with the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing.

Finally, always with the aim to make information available to all institution involved in combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism, each Member State is required to share the findings of its risk assessment with the Commission, the ESAs, and the other Member States.

5.5 Risk Assessment at Obliged Entities’ Level

The strategy on AML/CFT will be harmless, if entities involved in business relations are not called to play a significant role. This is why the Fourth Directive does not only calls such entities to carry out their own risk assessments to identify and assess the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing; the Fourth Directive also requires obliged entities to adopt proportionate measures (policies, controls, and procedures) to mitigate and manage effectively the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing at all levels, including EU and national levels. In other words, while Commission and Member States are mainly called to study the problems, obliged entities are called to study and to act accordingly.

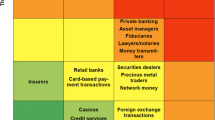

For the sake of clarity, according to Article 2, obliged entities are: (a) credit institutions; (b) financial institutions; (c) auditors, external accountants, tax advisors, notaries, and other independent legal professionals, where they participate, whether by acting on behalf of and for their client in any financial or real estate transaction, or by assisting in the planning or carrying out of transactions for their client concerning some particular activities;7 (d) trust; (e) estate agents; (f) other persons trading in goods to the extent that payments are made or received in cash in an amount of EUR 10,000 or more, whether the transaction is carried out in a single operation or in several operations which appear to be linked; and (g) providers of gambling services.

In this regard, Member States have to ensure that obliged entities take the appropriate steps and, more specifically, that such steps are proportionate to the obliged entities’ nature and size. For instance, a Member State may decide that individual documented risk assessments are not required where the specific risks of the sector are clear and understood.

Risk assessments by obliged entities have to take into account risk factors including those relating to their customers, countries or geographic areas, products, services, transactions, or delivery channels. For reasons already explained, obliged entities’ risk assessments are to be kept updated and made promptly available to the competent authorities.

Based on the findings of risk assessments, obliged entities have to adopt their steps on AML/CFT. The Fourth Directive gives general indications on such steps. More specifically, obliged entities’ policies are to aim for: (a) the development of internal policies, controls, and procedures, including model risk management practices, customer due diligence, reporting, record keeping, internal control, compliance management including, where appropriate with regard to the size and nature of the business, the appointment of a compliance officer at management level, and employee screening; and (b) where appropriate with regard to the size and nature of the business, an independent audit function to test the internal policies, controls, and procedures referred to in point (a).

Finally, the Fourth Directive boosts for an international cooperation amongst Member States on controls over obliged entities which operate establishments in another Member State. In this regard, it should be structured a double check on AML/CFT policies (i.e. sort of both “home Member State control” and “host Member State control”). More specifically, the home Member State should be: (a) responsible for supervising the obliged entity’s application of group-wide AML/CFT policies and procedures, and (b) allowed carrying out inspections also in the establishments located in the host Member State. The host Member State should be: (a) responsible for enforcing the establishment’s compliance with AML/CFT rules, (b) allowed carrying out inspections and offsite monitoring, and (c) entitled to appropriate and proportionate measures to address serious infringements of those requirements.

Finally, the competent authority of the home Member State should cooperate closely with the competent authority of the host Member State and should inform the latter of any issues that could affect their assessment of the establishment’s compliance with the host AML/CFT rules.

5.6 Third Countries Jurisdictions

All efforts by EU Institutions, Member States, and obliged entities might be softened or even annulled by those third countries which have deficiencies in their national AML/CFT regimes. Actually, the changing nature of money laundering and terrorist financing threats, which is made easier by a continuous evolution of technology and of the means in criminals’ hands, requires quickly adapting the legal framework as regards high-risk third countries. By doing so, important steps can be done to address efficiently existing risks and prevent new ones from arising.

In this regard, the Fourth Directive demands the Commission to identify the high-risk third countries to protect the proper functioning of the internal market. The Commission should take into account information from international organisations and standard setters in the field of AML/CFT, such as FATF public statements, mutual evaluation or detailed assessment reports or published follow-up reports, and adapt its assessments to the changes therein.

More specifically, high-risk countries will be identified on the basis of the following possible deficiencies: (a) legal and institutional AML/CFT framework, (b) powers and procedures in the hands of third countries’ institution to combat money laundering and the financing of terrorism, and (c) the effectiveness of the AML/CFT in addressing the relevant risks.

After high-risk third countries are identified, the Commission is entitled, within one month, to adopt acts restricting the free movement of capital to or such third countries involving direct investment—including in real estate—establishment, the provision of financial services or the admission of securities to capital markets.

5.7 Relations with Data Protection and Statistics

Just a brief overview has to be given about the relations amongst risk assessments, data protection, and statistics.

In this regard, the Fourth Directive provides that personal data have to be processed only for the purposes of the prevention of money laundering and terrorist financing. Other purposes, such as commercial purposes, are prohibited. The processing of data for the purposes of AML/CFT is expressly classified as a matter of public interest under the meaning of the Directive on data protection (95/46/EC).

Moreover, as accurate statistics are crucial for a proper risk assessment, the IV Directive sets out some requirements to make statistics comprehensive. More specifically, statistics have to include:

-

(a)

data measuring the size and importance of the different sectors which fall within the scope of the Directive, including the number of entities and persons and the economic importance of each sector;

-

(b)

data measuring the reporting, investigation, and judicial phases of the national AML/CFT regime, including the number of suspicious transaction reports made to the FIU, the follow-up given to those reports and, on an annual basis, the number of cases investigated, the number of personsprosecuted, the number of persons convicted for money laundering or terrorist financing offences, the types of predicate offences, where such information is available, and the value in euro of property that has been frozen, seized, or confiscated;

-

(c)

if available, data identifying the number and percentage of reports resulting in further investigation, together with the annual report to obliged entities detailing the usefulness and follow-up of the reports they presented;

-

(d)

data regarding the number of cross-border requests for information that were made, received, refused, and partially or fully answered by the FIU.

5.8 Brief Conclusive Comments

The introduction of a new strategy of risk-based regulation, such as the risk assessments under the Fourth Directive, is to be welcomed.

The risk assessments strategy reminds to a well-known way to organise power and competencies within the EU. Indeed, such a strategy requires different institutions, some at EU level and others at national level, to exercise their competences to reach one single and unitary scope. In other terms, each involved institution or obliged entity is called to play its part in a single music score, what has been referred as “concerto regolamentare europeo” (European regulatory concert).8 In another perspective, risk assessments strategy can be regarded as a set of “mixed administrative proceedings”.9 More specifically: (a) the circular flow of information amongst the institutions to prepare risk assessments reports; (b) the Commission’s power to recommend Member States the adoption of measures according to a “comply-or-explain” mechanism; and (c) the policies to be adopted by the obliged entities following the activities carried out by the Commission and the Member States, seem to create “hybrid administrative proceedings”.

In this regard, it can be stressed out that a guiding role in risk assessments strategy has been attributed to the Commission. However, works at EU level requires the continuous and real involvement of both Member States and obliged entities.

Moreover, a crucial role is to be played by obliged entities. Actually, only obliged entities are directly involved in business transactions: it should not, therefore, sound surprising that the Fourth Directive demands them to keep the findings of risks assessments and to convert such findings in sounding policies.

Finally, it should be also underlined that an excessive flow of information can lead to a malfunctioning of risk assessments strategy. In this regard, involved institutions have to put all efforts for a sounding implementation of the principle of proportionality so to orientate the gathering and the analysis of information towards what is really relevant for AML/CFT.

In conclusion, risk assessments may significantly boost AML/CFT policies. However, flows of information are useful only when policies really take place. In this regard, recent experiences teach that a lot is yet to be done.

5. Notes

-

1.

Barone, R. & Masciandaro, D. (2008) “Worldwide Anti-Money Laundering Regulation: Estimating Cost and Benefits”, Global Business & Economic Review, 243–264.

-

2.

Black, J. (2005) “The emergence of risk-based regulation and the new public management in the United Kingdom”, Public Law, Autumn, pp. 512–549; Hampton, P. (2004) Reducing Administrative Burdens: Effective Inspection and Enforcement, London: HM Treasury Department; Hutter, B. (2005) The Attractions of Risk Based Regulations: Accounting for the Emergence of Risk Ideas in Regulations, London: Centre for Analysis of Risk and Regulation (CARR) Discussion Paper DP 33, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

-

3.

Black, J. & Baldwin, R. (2010) “Really Responsive Risk-Based Regulation”, Law & Policy, April, Vol. 32, pp. 181–213.

-

4.

Black, J. & Baldwin, R. (2012) “When risk-based regulation aims low: Approaches and challenges”, Regulation & Governance, Vol. 6, pp. 2–22.

-

5.

Dalla Pellegrina, L. & Masciandro, D. (2009) “The Risk-Based Approach in the New European Anti-Money Laundering Legislation: A law and Economics View”, Review of Law & Economics, Vol. 5, pp. 931–952; Ross, S. & Hannan, M. (2007), “Money Laundering Regulation and Risk-Based Decision Making”, Journal of Money Laundering Control, pp. 106–115.

-

6.

FAFT (2012) International Standards on Combating Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism & Proliferation, Financial Action Task Force, Paris.

-

7.

These activities are: (a) buying and selling of real property or business entities; (b) managing of client money, securities or other assets; (c) opening or management of bank, savings or securities accounts; (d) organisation of contributions necessary for the creation, operation or management of companies; and (e) creation, operation or management of trusts, companies, foundations, or similar structures.

-

8.

Cassese, S. (2012) Istituzioni di diritto amministrativo, Torino: Giuffrè Editore, p. 126.

-

9.

Della Cananea, G. (2004) “The European Union’s Mixed Administrative Proceedings”, Law and Contemporary Problems, Winter, pp. 197–218.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tonnara, P. (2016). Risk Assessment. In: Siclari, D. (eds) The New Anti-Money Laundering Law . Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29099-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29099-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-29098-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-29099-7

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)