Abstract

The growing interest in patient navigation has caused a growth in published health literature that expounds on its definition and those who serve as patient navigators. Patient navigation provides a variety of services for cancer patients who may be culturally differential, uninsured, and impoverished. The role and responsibilities of the patient navigator vary, but the overall focus is on identifying and assisting with barriers that cancer patients are confronted with to cancer education and treatment.

Patient navigators are also identified by the following titles:

-

Case managers.

-

Comadres.

-

Community health aids.

-

Community health workers.

-

Lay health workers.

-

Nurses.

-

Promotoras.

-

Social workers.

The titles above indicate that patient navigators are often members of the community that they serve and that some cancer treatment programs may employ navigators who are ethnically concordant to the target population. It is also important to note that patient navigators are more flexible in problem solving to help a patient overcome barriers to care as opposed to the provision of a predefined set of services.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

How Patient Navigation Is Defined

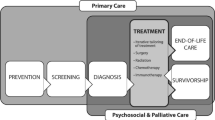

The term patient navigation was created by Dr. Harold P. Freeman, who partnered with the American Cancer Society (ACS) to create the first patient navigation program in Harlem, New York [1]. Patient navigation refers to the assistance offered to patients living with cancer in navigating through the complex health-care system to overcome barriers in accessing quality care and timely diagnosis and treatment. Navigation programs most often focus on helping patients with positive screening tests complete the diagnostic workup expeditiously [2, 3]. Navigation has also targeted patients undergoing initial cancer treatment [4] and in palliative care [5]. Navigation encompasses several potential forms of instrumental (defined as the provision of tangible aid and services that directly assist a person in need) [6] and emotional support for individuals with cancer. Navigators assess patients’ needs and, in collaboration with the patient, develop a plan to overcome barriers to high quality care [7].

Instrumental navigation services help patients access the cancer care system and overcome barriers to care. Navigators provide assistance with insurance, finances, transportation, language barriers, communication with the doctor, securing childcare, obtaining relevant information, and coordination of cancer care [2, 7]. Because cancer is usually an emotionally charged and life-changing experience, navigators also may offer emotional support to patients and families by responding to emotional distress, expressing empathy, listening supportively, and providing comfort. Several definitions of patient navigation have been published [2, 8–10]. Although variations do exist, patient navigation generally is described as a barrier-focused intervention that has the following common characteristics:

-

Patient navigation is provided to individual patients for a defined episode of cancer-related care (e.g., evaluating an abnormal screening test). Navigation in cancer-related care is not episodic (per clinic basis) but encompasses the phases of cancer treatment. The navigation skill sets employed may vary depending upon whether a patient is in the early or advanced stage of disease, palliative care, clinical trial, etc.

-

Although tracking patients over time is emphasized, patient navigation has a definite endpoint when the services provided are complete (e.g., the patient achieves diagnostic resolution after a screening abnormality).

-

In low-income women with breast and other gynecological-related cancers, patient navigation has improved adherence to their radiation and chemotherapy regimens [11].

-

Patient navigation targets a defined set of health services that are required to complete an episode of cancer-related care.

-

Patient navigation services focus on the identification of individual patient-level barriers, as well as systemic barriers, to accessing cancer care.

-

Patient navigation aims to reduce delays in accessing the continuum of cancer care services, with an emphasis on timeliness of diagnosis and treatment, reduction in the number of patients lost to follow-up, and increasing the quality of the clinical encounter.

Background

Former president of the American Cancer Society (ACS) , Harold Freeman , has been extensively credited as the founder of patient navigation programs that were specifically designed to explore cancer care barriers among poor Americans [12]. The ACS-funded Breast Health Patient Navigation Program used patient navigators to provide support to women that sought diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer [13]. Dr. Freeman developed the patient navigator program at the Harlem Hospital Center in 1990 in response to the complex barriers that marginalized Americans faced while trying to access cancer care services. Those complex barriers to health care included (1) extensive financial constraints resulting in the lack of health insurance and inexpensive cancer care services, Medicaid or Medicare exclusion, and lack of employment-related health insurance; (2) operational barriers including shortages in transportation services, geographic restrictions between patient and health-care facilities, lack of patient reminders, and confusing cancer-related health information; and (3) sociocultural barriers including a lack of social support and poor health literacy [14]. Parker and colleagues [15] found that these marginalized patients were at an increased risk of receiving ineffective care throughout the cancer continuum: screening, prompt follow-up of suspicious results, adequate treatment, and survivorship observation.

Dr. Freeman’s patient navigation program was instrumental in expanding screening and education services in the Harlem community by having specific community members offer services to women that had a suspicious result [14]. More than 40 % of patients diagnosed with breast cancer between 1995 and 2000 were diagnosed early in the course of the disease as compared to less than 10 % between 1964 and 1986 at the same facility; there was also an increase in 5-year survival rates to around 70 % during that same time period [12].

The work of Dr. Freeman and the success of the patient navigation program have more recently encouraged governmental support. In 2001, community-based programs such as patient navigation programs were recommended to obtain funding to provide cancer education, screening, treatment, and other support services [14]. The Patient Navigation Outreach and Chronic Disease Prevention Act of 2005 approved $25 million in funding for more than 5 years from programs that successfully used patient navigation to improve health outcomes [13]. In the same year, the National Cancer Institute’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities supported the Patient Navigation Research Program (PRNP) to examine the effectiveness of community-based patient navigation programs [14]. Wells and colleagues [14] also noted that in 2006, there were six sites supported by the Center for Medicare Services to reduce access barriers to screening, diagnosis, and cancer treatment in minority Medicare beneficiaries.

Key Personnel

The complexity of cancer care requires patients to navigate the cancer center system for treatment as well as the community system for health, community, and social resources between treatment appointments. Hospital-/cancer center-based navigation enables patients to effectively navigate the hospital system, while community-based navigation enables patients to effectively engage and navigate community-based services and support systems that can facilitate the cancer center/hospital system interactions and potentially improve the cancer treatment experience.

There is no accepted definition of patient navigation, nor is there an assumption of who would be most competent to provide patient navigation activities [13]. In a study conducted by Wells and coauthors [14], the results from their literature review identified four areas in which patient navigators frequently intercede: (1) providing social support, (2) addressing patient barriers to cancer care, (3) providing health education about cancer across the cancer continuum from prevention to treatment, and (4) overcoming health system barriers. In a nutshell, these same duties have been categorized by Jean-Pierre et al. [16] into two types of interventions: instrumental and relationship. Instrumental interventions are organizational or operational, such as transportation services and cancer information, but relationship interventions are personal ones that build and strengthen the connection between the patient and provider [16].

After reviewing published literature [14–21], the patient navigator also has several alternate titles, but the role and responsibilities are yet the same. Originally, the patient navigator was a hands-on patient representative that concentrated on addressing the specific needs of patients by recognizing and eliminating barriers to timely receipt of care [26]. Dohan and Schrag [25] noted that the role of a patient navigator needs more refining accompanied by specialized training. Defined roles and standardized training should allow the representative that best serves the patients to fulfill the patient navigator role. Currently, patient navigators have many titles, including nurses, community health workers, case managers, social workers, community health aides, lay health workers, comadres, and promotoras. These services are often provided by a lay patient navigator, but there are many programs that utilized navigators with undergraduate degrees, graduate degrees, nurse navigators, social workers, health educators, clinicians, research assistants, as well as cancer survivors [14]. The following sections will highlight four types of individuals who provide patient navigation services.

Nurse Navigator

The term nurse navigator was introduced to the oncology health-care setting in recent years but seems to continue to fall under the broad heading of patient navigation [28]. In 2011, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [29] stated that the patient navigator is most often a nurse and used the term patient navigator interchangeably with case manager. Nurse navigation is defined as patient navigation services implemented by a bachelor’s prepared RN, often with oncology experience, who offers cancer education, supportive care, and appropriate referrals after diagnosis and throughout treatment for breast cancer [21]. These trained professionals assist patients with scheduling doctor’s appointments as well as making knowledgeable decisions regarding treatment. Nurse navigation also consists of providing tips on coping with patients' prognoses, making sure that patients stay on track with their treatment plans, handling insurance issues, and offering emotional support [29, 30].

Seek and Hogle [29] noted that due to the complex responsibilities of a patient navigator, a nurse practitioner or advanced oncology nurse would be best suited for the role [30]. A nurse navigator is able to provide services at the initial diagnosis and can enhance cancer care throughout the cancer care continuum, whether it ends in survivorship or end-of-life care [31]. However, their focus is on treatment delivery issues within the hospital/cancer center system. Oncology nurses are an essential component to the education of not only patients but family members of patients, as well as the community [32]. They can translate complicated information into lay terminology for cancer patients, family members, and care givers [33]. One of the most essential responsibilities of an oncology nurse is to explain cancer-related information that is given to the patient by other health-care providers and to help them in comprehending any treatment plans [31]. Oncology nurses provide information needed to understand treatment side effects, nutrition, coping strategies, and other behaviors that improve care [34]. They can show patients how to effectively navigate the cancer medical system until that patient has the ability to navigate alone [20]. Oncology nurse navigators are also active members of the health-care team who can provide input on treatment schedules, education provided to the patient and family, and any other valuable information to support the patient [32]. They can also initiate difficult discussions between either the patient and family members or physicians and help them make difficult choices that affect their individual cancer care [20].

Case Managers

Case managers are health-care professionals who help provide a variety of services that assist individuals and families cope with complex physical or mental health medical conditions. The purpose of the case manager is to increase effectiveness, enhance treatment adherence, offer patients with needs services with the health-care facility and community, and guarantee patient-centered care [35]. To do so, the case manager job description is centered on working closely with clients and their families to identify their needs, goals, and the necessary resources to meet those goals. Instead of managing the clients, case managers help clients manage their own difficult situations. Case managers are vital members of the health-care professional team. When a client reaches the optimal quality of life, all additional support systems benefit, including the client, their family, and their health-care providers. Since case managers can be found in both medical and social service work environments, duties can vary depending on employment. The duties of a case manager are as follows [36]:

-

Reach out to clients assigned by his or her supervisor to assess their most urgent needs, appraise the situation, and listen to the clients’ concerns.

-

Develop a detailed plan of action to meet these needs, set goals, and find necessary resources to meet the goals.

-

Offer counseling for patients in either individual or group settings.

-

Consult with other external agencies to provide support services and resources.

-

Keep comprehensive records of clients’ progress throughout the process, including every call, referral, and home visit.

-

Maintain confidentiality, respect privacy, and preserve the clients’ routine and independence as much as possible.

-

Stay in touch with clients to ensure the services were beneficial and that their needs are still met after pointing clients in the right direction for services.

Medical case managers usually work in various health-care facilities, such as hospitals, nursing homes, clinics, and rehabilitation centers. Social service case managers are employed mostly by public and nonprofit organizations, including schools, housing commissions, and homeless shelters. Typically, case managers specialize in a particular area, such as physical health, mental health, aging, disability, child welfare, addiction, or occupational services. Hesselgrave [37] noted that case managers bear a responsibility for coordinating oncology services, in addition to counseling services, home health services, physical therapy, and more.

Most case managers are professionals who have a background in either social work or nursing. Successful case managers must possess strong communication skills and problem management strategies. He or she must also be organized, detail oriented, and knowledgeable. Usually, they obtain a bachelor’s or master’s degree, while some states also require licensing since the managers play such a prominent role in patient care. Case managers hold positions where they are strong advocates to ensure clients’ unique needs are met.

Social Workers

Although patient navigation is thought to be a very recent idea, it borrows many concepts from social work [13]. A health-care social worker takes on a variety of tasks depending on the environment in which they choose to work. They work with people who have chronic and acute health-care needs such as HIV, diabetes, heart conditions, and trauma [21, 26, 38]. They work in clinics, hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living, mental health, and other health-care settings as well. In the hospital, they help clients plan their discharge home. They coordinate services such as home health care, medical equipment rentals, transportation to follow up doctor visits, and other related activities. They will help clients get admitted to inpatient and outpatient services, find funding sources, fill out paperwork, and find support resources for families. They assist with educational classes on things such as childcare, Alzheimer’s management, living with cancer, and HIV. They are concerned with all components of health and mental health care. They also participate in and advise on health-care policy, services, and legislative issues [39]. Although many social workers primarily work in an office setting, they also spend a great deal of time outside of their office setting to visit and check on the status and health of their client.

Social workers have been known to serve the most economically disadvantaged populations [39]. Those disadvantaged populations include those that are unaware of available services; discouraged from taking advantage of services due to lack of trust, difficult programming, or poor access to available services; refuse to participate in available programs; or withdrawn from available services [40]. With a dedication to assist vulnerable populations, social workers have become a very cost-effective resource [24]. They have been utilized as patient navigators because of the ability to help cancer patients get services and coordinate the health-care team of cancer patients [31]. The Affordable Care Act indicates the duties of a patient navigator include increasing public awareness about health insurance, cultural and linguistically sensitive health-care information, assist in health-care selection, and offer recommendations to appropriate services that handles grievances, complaints, or other questions [23]. Darnell [23] maintains that social workers are well suited to do the previously mentioned duties effectively.

Community Health Aides, Lay Health Workers, Comadres, and Promotoras

In contrast to social workers and hospital-based navigators, community health aides, lay health workers, comadres, and promotoras spend the majority of their time in the field working directly with their patients/clients and little time in the office setting. Since they usually live in the community, and often neighborhoods they serve, they and their patients/clients daily lives overlap professionally as well as socially. This facilitates the development of richer interpersonal trust relationships and understanding of community-based barriers and perceptions that may exist with navigators living outside of the community or neighborhood.

Community health workers (CHWs) have been described as serving in areas of community outreach and follow-up by helping patients to access health-related services. In contrast to social workers and other personnel listed, CHWs are lay people who commonly live (rather than work) in the community and have received training through formal (state certification) or informal (local organization/position specific) training. They also have provided informal counseling, social support, health education, screening, detection, and basic emergency care [41, 42].

By identifying and addressing barriers to adherence to cancer screening or treatment recommendations and working with patients to negotiate tailored plans of care, CHWs have improved care access and cancer screening behaviors, as well as reduced health-care costs in minority communities, including Black and Hispanic communities [43–45]. Community health workers (CHWs) can be broadly defined as community members who serve as connectors between health-care consumers and providers to promote health among groups that have traditionally lacked adequate access to care [46]. CHWs are referred to by more than 40 different terms. These names include “lay health advisors,” “paraprofessionals,” “health aides,” “comadres,” “promotoras,” “patient navigators,” and “natural helpers.” Community health workers play influential roles in the health-care delivery system even though they are not often considered to be formal members of a medical team. They often help link people to the necessary health-care information and services that they may be lacking at the time. Community health workers work in all geographic settings, including rural, urban, and metropolitan areas; border regions (colonias, i.e., comadres and promotoras); and the Native American nations. Community health workers that are hired by health-care agencies often have a disease- or population-based skill set such as providing education or enhancing the nutrition of those who may be living with the various forms of cancer, heart disease, or diabetes. Teaching home-based chronic disease self-management skills is also an important component of their skill set. Community health workers may [47]:

-

Staff tables at community events.

-

Provide health screenings, referrals, and information.

-

Help people complete applications to access health benefits.

-

Visit homes to check on individuals with specific health conditions.

-

Drive clients to medical appointments.

-

Deliver health education presentations to schoolchildren and their parents and teachers.

Although their roles vary depending on locale and cultural setting, they are most often found working in low-resource communities where people may have limited resources, lack access to quality health care, lack the means to pay for health care, speak English fluently, or have cultural beliefs, values, and behaviors different from those of the dominant Western health-care system [18, 22, 39, 48]. In these communities, community health workers play an integral role in bridging the chasm between the community and the health-care system. The role and responsibilities of a community health worker may consist of the following [2, 42, 47–51]:

-

Helping individuals, families, groups, and communities develop their capacity and access to resources, including health insurance, food, housing, quality care, and health information.

-

Facilitating communication and client empowerment in interactions with health-care/social service systems.

-

Helping health-care and social service systems become culturally relevant and responsive to their service population.

-

Helping people understand their health condition(s) and develop strategies to improve their health and well-being.

-

Helping to build understanding and social capital to support healthier behaviors and lifestyle choices.

-

Delivering health information using culturally appropriate terms and concepts.

-

Linking people to health-care/social service resources.

-

Providing informal counseling, support, and follow-up.

-

Advocating for local health needs.

-

Providing health services, such as monitoring blood pressure and providing first aid.

-

Making home visits to chronically ill patients, pregnant women and nursing mothers, individuals at high risk of health problems, and the elderly.

-

Translating and interpreting for clients and health-care/social service providers.

-

The success of CHWs’ efforts has caused many government agencies, nonprofit organizations, faith-based groups, and health-care providers to create paid positions for community health workers to help reduce, and in some cases eliminate, the persistent disparities in health care and health outcomes in underprivileged communities [47]. Something very unique about CHWs is that they oftentimes reside in the community that they regularly serve.

Patient Navigation Intervention Sites

Patient navigation has quickly grown into a nationally recognized model for the delivery of health-care services [2]. As the patient navigation model is becoming more and more utilized within the health-care delivery system, it is important to note that patient navigators are not just found within the hospital system. In order to improve health outcomes for cancer patients that often have to overcome daunting barriers, patient navigation is now being utilized outside the hospital in facilities such as community cancer centers. There has also been a push for primary care providers to employ the patient-centered medical home model to aid in the reduction of cancer care disparities. Dr. Freeman understood that there needed to be a more innovative way to attack cancer, one that eliminated economic and cultural barriers to health care, early screening, and treatment and that needed to be implemented in the communities around America [2]. The implementation of patient-centered medical homes, as well as the overall evolution of the patient navigation model has helped to breathe new life into this fight against cancer and cancer care disparities.

Patient-Centered Medical Home

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model of care was given considerable backing because of how the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 promoted the expansion of innovative styles of primary care and coordination of care services [51]. Henderson and colleagues [51] noted that the purpose of the PCMH is to offer patients a facility where they are seen by the same members of a health-care team, including a care coordinator, who is usually a nurse [51]. Patient-centered care is thought to be a very important component in reducing racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in health outcomes and access to care [52]. The PCMH has become a widely accepted approach to primary care delivery in the United States, with no signs of deviating from this approach [53]. The PCMH has focused on providing coordinated care, which has been shown to improve health outcomes, enhance patient satisfaction, and minimizing costs [52]. This health-care model is built of general principles that balance one another and feed into an inclusive idea of primary care delivery including (1) having a personal physician, (2) comprehensive orientation, (3) physician-led medical practice, (4) coordinated care, (5) focus on quality and patient safety, and (6) improved access [53]. Patient navigators are influential in this coordination of care that makes the PCMH model of care so popular. The oncology patient-centered medical home (OPCMH) model has stemmed from PCHM. Studies have shown that OPCMH model reduces cancer-related hospital admissions, as well as the number of hospital admission days for chemotherapy patients [54].

Community Cancer Centers

Based on the notion that community members trained to be patient navigators can be valuable in eliminating diagnosis and treatment barriers of cancer, community patient navigation programs denote the prevention component of the Freeman model in encouraging the community to get screened, potentially reducing disparities in cancer care [55]. With the anticipation of patient-centered care from not only cancer patients but also from accrediting bodies, community cancer centers have considerable demands to implement patient navigation programs [56]. The Avon Foundation Community Education and Outreach Initiative (CEOI) addresses barriers to cancer care through the use of community-based patient navigation. Patient navigation programs within community cancer centers use both untrained and trained volunteers to (1) inform the community about routine breast care, breast cancer, and screening options; (2) coordinate breast health events such as seminars, lunch and learns, and community health fairs; (3) lectures on breast health and breast cancer in the workplace, places of worship, and town hall settings; (4) extend reminders to encourage the community to make and attend all mammogram appointments; and (5) offer educational support through educational outreach activities [55]. The CEOI is a single documented case of where a community patient navigation model was utilized within a community cancer center, but more centers are adopting this trend of incorporating patient navigation to address cancer care barriers of its community members.

Patient Navigation in the Emergency Department

Patient navigation programs give assistance and direction to persons with the objective of enhancing access to cancer care while eliminating the barriers to timely, quality of care [12]. Barriers such as low socioeconomic standing and cultural and religious beliefs often are the foundation for disparities in ethnic groups, but poverty is the most significant cause of disparities in Americans [57]. Along with the previously mentioned barriers, insurance status has also proven to be a significant barrier to adequate cancer care. Although cancer is often associated with patients of advanced age, Calhoun and associates [26] noted that compared to Whites, racial and ethnic minorities receive poorer health care even with comparable insurance status, age, income, and disease severity. Adding to the issue of lower-quality cancer care, there are difficulties in obtaining timely cancer care that include medical distrust, poor health literacy, lack of cultural and language concordance, and misunderstanding about cancer [58]. For patients that live in rural areas, barriers to access of health care and transportation to health-care facilities has been shown to inhibit prompt cancer treatment [57].

Patient navigation is a model of care that has been proposed to alleviate the effects of health disparities [26], but significance of this concept does not end there. Patient navigation has developed into a model that has grown from addressing the needs of marginalized populations to navigating every cancer patient throughout the cancer continuum [35].

Barriers surrounding lack of insurance have been shown to have a negative impact on cancer-related health outcomes. One major resource for medical care for the under- or uninsured is the emergency department. Emergency department use has increased to almost 25 %, to around 110 million visits between 1992 and 2002 [61], According to the 2003 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, there were about 114 million emergency department visits that year, with less than 20 % considered actual emergencies [60]. Although health-care costs in the United States are more than in other nations across the globe, 13 million Americans are underinsured with 46 million Americans uninsured [61].

Long recognized as a safety net provider, the emergency department is one usual source of care for those who are affected by barriers to continuity relationships with physicians [62]. Community health centers (CHC) also provide health care, but CHCs only provide a portion of care needed for people without usual access to care [61]. CHCs also come with their own set of barriers, because patients often have to pay a portion of the costs for any services that are needed during the appointment [63]. Although emergency departments are guaranteed medical care for many patients, there are far less acute settings that can provide much of medical care that is needed [64].

Patient navigation has traditionally addressed barriers to access of care to underserved and underinsured populations and that utility has now been seen in action in the emergency department. A study conducted by Enard and Ganelin [27] found that patient navigation decreased the chances of return emergency department visits among those that use the emergency department for usual care. This study also found that there was a considerable decrease in those that did make return visits to the emergency department for usual care over a 12-month time span [27]. A 2010 study by Roby and associates [65] found that over a 19-month time frame, patients were less likely to make multiple emergency department visits if they had previously received case management through medical homes. In a study that utilized rigorous clinical case management for frequent emergency department users in urban areas, the researchers found considerable reductions to acute hospital services, including psychosocial issues [66].

Patient navigation has the potential to remedy another issue that emergency departments are presented with and that is the issue of overcrowding. Emergency department use that leads to overcrowding has the misconception of being attributed solely to those patients that are either underinsured, uninsured, or lack a primary care physician. The barrier that is often overlooked in the scenario is the possibility of a poor patient provider interaction. Patient provider relationship factors such as mistrust and poor communication styles have been associated with poor patient satisfaction, lack of preventive care services, lack of referral options, and poor patient follow-up on treatment [67]. Successful communication is a crucial component in cancer care and allows patients to make informed treatment decisions and also adherence to treatment options [68]. Weber and associates [59] found that the misconception that patients who utilize the emergency department either do not have a primary care physician or health insurance coverage can contribute to the assessment that emergency department overcrowding is only the result of misuse by a small marginalized segment of the US population. Policy makers and health-care officials should understand that not all issues of overcrowding or improper use of emergency departments are due to poor patient provider relationships but can be attributed to other systemic barriers that contribute to health disparities among vulnerable populations in the United States.

Summary

Patient navigation has been shown to be an intervention whose sole purpose is to reduce barriers to cancer care throughout the entire cancer care continuum. The success of this approach has led to its implementation in the management of non-oncologic chronic disease management. This intervention has been met with governmental support to ensure that the goals and aims of the patient navigation model are achieved. The evolution of patient navigation has not caused the model to deviate from Dr. Freeman’s initial goals for the first patient navigation program, but it has grown to include many different key players in the health-care system. Not only has patient navigation evolved to include other key health-care personnel, but it has also expanded outside the traditional health-care system to better serve the marginalized underserved population Dr. Freeman set out to help in 1990. This chapter has shown how patient navigation is a model of care that not only ensures timely care for cancer patients, but its principles are now being used in the emergency department to help eliminate disparities in primary care of those who are marginalized, underinsured, or uninsured. The patient navigation model is proving to be an intervention that has shaped how patients, whether they have cancer or not, navigate through the health-care system and receive optimal care.

References

Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3(1):19–30.

Freeman HP. The origin, evolution, and principles of patient navigation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(10):1614–7.

Jandorf L, Jandorf A, Fatone P, et al. Creating alliances to improve cancer prevention and detection among urban medically underserved minority groups. Cancer. 2006;107(8):2043–51.

Baquet C, Baquet K, Mack S, et al. Maryland’s special populations network. Cancer. 2006;107(8):2061–70.

Gabram SGA, Lund J, Gardner N, et al. Effects of an outreach and internal navigation program on breast cancer diagnosis in an urban cancer center with a large African-American population. Cancer. 2008;113(3):602–7.

Fischer S, Fischer A, Sauaia J. Patient navigation: a culturally competent strategy to address disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(5):1023–8.

Heaney CA, Israel BA. Social networks and social support. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 187.

Epstein R. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007.

Newman-Horm PA. C-Change. Cancer Patient Navigation: Published Information. Washington, DC: C-Change; 2005.

Cancer Care Nova Scotia. Cancer Patient Navigation Evaluation: Final Report. Cancer Care Nova Scotia: Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; 2004.

Guadagnolo BA. Metrics for evaluating patient navigation during cancer diagnosis and treatment: crafting a policy-relevant research agenda for patient navigation in cancer care. Cancer. 2011;117(15):3563–72.

Ramsey S, Ramsey E, Whitley V, et al. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of cancer patient navigation programs: conceptual and practical issues. Cancer. 2009;115(23):5394–403.

Darnell JS. Patient navigation: a call to action. Soc Work. 2007;52(1):81–4.

Wells K, Wells T, Battaglia D, et al. Patient navigation: state of the art or is it science? Cancer. 2008;113(8):1999–2010.

Parker V, Parker J, Clark J, et al. Patient navigation: development of a protocol for describing what navigators do. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(2):514–31.

Jean Pierre P, Jean Pierre S, Hendren K, et al. Understanding the processes of patient navigation to reduce disparities in cancer care: perspectives of trained navigators from the field. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(1):111–20.

Paskett E, Paskett JP, Harrop K. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):237–49.

Fiscella K. Patient-reported outcome measures suitable to assessment of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(15):3601–15.

Fowler T, Fowler C, Steakley AR, Garcia J, Kwok LM. Reducing disparities in the burden of cancer: the role of patient navigators. PLoS Med. 2006;3(7):e193–976.

Davis C. Unfair care. Nurs Older People. 2007;19(8):12–3.

Hook A, Hook L, Ware B, Siler A. Breast cancer navigation and patient satisfaction: exploring a community-based patient navigation model in a rural setting. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39(4):379–85.

Ingram M, Ingram K, Reinschmidt K, et al. Establishing a professional profile of community health workers: results from a national study of roles, activities and training. J Community Health. 2012;37(2):529–37.

Darnell JS. Navigators and assisters: two case management roles for social workers in the affordable care act. Health Soc Work. 2013;38(2):123–6.

Battaglia T, Battaglia L, Burhansstipanov S, Murrell A. Assessing the impact of patient navigation: prevention and early detection metrics. Cancer. 2011;117(S15):3551–62.

Dohan D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients. Cancer. 2005;104(4):848–55.

Calhoun E, Whitley E, Esparza A, et al. A national patient navigator training program. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(2):205–15.

Enard K. Reducing preventable emergency department utilization and costs by using community health workers as patient navigators. J Healthc Manag. 2013;58(6):412–27.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. The case manager or patient navigator: Providing support for cancer patients during treatment and beyond. 2011. http://www.nccn.com/living-with-cancer/understanding-treatment/152-casemanagers-for-cancer-patients.html. Accessed 3 May 2014.

Seek A. Modeling a better way: navigating the healthcare system for patients with lung cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(1):81–5.

Pedersen A, Pedersen T. Pilots of oncology health care: a concept analysis of the patient navigator role. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(1):55–60.

Wilcox B, Wilcox S. Patient navigation: a “win-win” for all involved. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(1):21–5.

Vaartio Rajalin H. Nurses as patient advocates in oncology care. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15(5):526–32.

Lackey NR. African american women's experiences with the initial discovery, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28(3):519–27.

DeSanto Madeya S, Bauer Wu A. Activities of daily living in women with advanced breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(4):841–6.

Shockney L. Evolution of patient navigation. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14(4):405–7.

Lemak C. Collaboration to improve services for the uninsured: Exploring the concept of health navigators as interorganizational integrators. Health Care Manage Rev. 2004;29(3):196–206.

Hesselgrave B. Case managers’ effect on oncology outcomes. Case Manager. 1997;8(1):45–8.

Ell K, Ell B, Vourlekis P, Lee B. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2007;44(1):26–33.

Abell N. Preparing for practice: motivations, expectations and aspirations of the MSW class of 1990. J Soc Work Educ. 1990;26(1):57–64.

Watson J. Active engagement: strategies to increase service participation by vulnerable families. New South Wales Centre for Parenting and Research Discussion paper, Department of Community Services, Ashfield. 2005. http://www.community.nsw.gov.au/documents/research_active_engagment.pdf.

Earp J. Increasing use of mammography among older, rural African American women: results from a community trial. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):646–54.

Liberman L. Carcinoma detection at the breast examination center of Harlem. Cancer. 2002;95(1):8–14.

Oluwole S. Impact of a cancer screening program on breast cancer stage at diagnosis in a medically underserved urban community. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196(2):180–8.

John Hopkins Medicine. Community Health Workers. Department of Medicine. http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/Medicine/sickle/chw/. Accessed 13 May 2014.

Community Health Worker. Explore health careers Website. http://explorehealthcareers.org/en/Career/157/Community_Health_Worker. Accessed 15 May 2014.

Vargas R, Vargas G, Ryan C, Jackson R, Rodriguez H. Characteristics of the original patient navigation programs to reduce disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(2):426–33.

Zuvekas A. Impact of community health workers on access, use of services, and patient knowledge and behavior. J Ambul Care Manage. 1999;22(4):33–44.

Love MB. Community health workers: who they are and what they do. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(4):510–22.

Meade C, Meade K, Wells M, et al. Lay navigator model for impacting cancer health disparities. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29(3):449–57.

WestRasmus E, WestRasmus F, Pineda Reyes M, Tamez J. Promotores de salud and community health workers. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(2):172–82.

Henderson S, Henderson C, Princell S. The patient-centered medical home. Am J Nurs. 2012;112(12):54–9.

Epstein RM, Epstein K, Fiscella CS, Lesser KC. Why the nation needs. A policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff. 2010;29(8):1489–95.

Hoff T, Hoff W, Weller M. The patient-centered medical home: a review of recent research. Med Care Res Rev. 2012;69(6):619–44.

Sprandio JD. Oncology patient-centered medical home. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):SP191–2.

Mason TA, Mason WW, Thompson D, Allen D, Rogers S, Gabram-Mendola KR. Evaluation of the avon foundation community education and outreach initiative community patient navigation program. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(1):105–12.

Pratt Chapman M, Pratt Chapman A. Community cancer center administration and support for navigation services. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29(2):141–8.

Schwaderer KA. Bridging the healthcare divide with patient navigation: development of a research program to address disparities. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11(5):633–9.

Mandelblatt JS. Equitable access to cancer services: a review of barriers to quality care. Cancer. 1999;86(11):2378–90.

Weber E, Weber J, Showstack K, Hunt D, Colby M. Does lack of a usual source of care or health insurance increase the likelihood of an emergency department visit? Results of a national population-based study. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(1):4–12.

Brim C. A descriptive analysis of the non-urgent use of emergency departments. Nurse Res. 2008;15(3):72–88.

Commonwealth Fund. Health insurance overview. 2006. www.cmwf.org/General/General_show.htm?doc_id=318887. Accessed 22 June 2014.

Sarver J. Usual source of care and nonurgent emergency department use. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(9):916–23.

McCarthy M. Referral of medically uninsured emergency department patients to primary care. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(6):639–42.

Petersen LA. Nonurgent emergency department visits: the effect of having a regular doctor. Med Care. 1998;36(8):1249–55.

Roby DH, Roby N, Pourat MJ, et al. Impact of patient-centered medical home assignment on emergency room visits among uninsured patients in a county health system. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(4):412–30.

Okin R. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18(5):603–8.

Street RL, Street KJ, O'Malley LA, Cooper P. Understanding concordance in patient-physician relationships: personal and ethnic dimensions of shared identity. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(3):198–205.

Sheppard V, Sheppard I, Adams R, Lamdan K. The role of patient-provider communication for black women making decisions about breast cancer treatment. Psychooncology. 2011;20(12):1309–16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bonner, T., Sherman, L.D., Hurd, T.C., Jones, L.A. (2016). Patient Navigation. In: Todd, K., Thomas, Jr., C. (eds) Oncologic Emergency Medicine. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26387-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26387-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-26385-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-26387-8

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)