Abstract

Nowadays, the role of values in the configuration of technology appears as a crucial topic. (1) What technology is and ought to be depends on values. These values can be considered in a twofold framework: the structural dimension and the dynamic perspective. (2) Axiology of technology takes into account the existence of these values—structural and dynamic—of its configuration, because technology is not a value-free undertaking and it has an “internal” side as well as an “external” part. Thus, axiology of technology studies the role of the “internal” values of technology (those characteristic of technology itself) and the task of “external” values of technology (those around this human undertaking). (3) Subsequently, the ethics of technology deals with ethical values. In this regard, the ethical analysis of technology is also twofold: there is an endogenous perspective (as a free human undertaking related to the creative transformation of the reality) and an exogenous viewpoint, insofar as technology is related to other human activities within a social setting.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Within the context of the relevant improvements of technology in recent times, the analysis of the problem of values—what the role of values in the configuration of technology is and ought to be—appears as a crucial topic. While this relation between technology and values has certainly received attention in the past,Footnote 1 there is now an increasing interest in this connection, to the extent that it can be deemed to be a key issue. The new scenario has come about for several reasons, among which two stand out: the frequent reflection on values regarding information and communication technologies (ICTs) [cf. Ricci 2011], which includes attention to ethical reflections on this influential technological branchFootnote 2; and the acceptance nowadays of technology as value-laden instead of being considered as value-free,Footnote 3 which opens the door to new ethical analyses of technology as a human undertaking.

Moreover, insofar as technology is value-laden, these values can lead us to the structural dimension of this human entreprise or can clarify the dynamic perspective of this social undertaking. These aspects should be open to an axiological analysis, which can consider the role of the “internal” values (those characteristic of technology itself) as well as the role of the “external” values (those around this human undertaking). In addition, the ethical values in technology—both endogenous and exogenous—will be at the focus of attention, due to their relevance for this free human activity.

Accordingly, the philosophical analysis here will follow three main steps. First, the characterization of the framework of values in technology based on the distinction between “structure” and “dynamics.” This approach depends on the features of “technology” as being conceptually different from “science,” which also requires taking into account what is “technoscience.” Second, the role of values in the sphere of axiology of technology, where several kinds of values are involved (economic, social, cultural, ecological, etc.). Some of them can be seen as being “internal” to technology, whereas others might belong to the “external” sphere to this human entreprise. Third, the role of the specific values of ethics in technology, which includes the endogenous perspective and the exogenous viewpoint.

Technology and the Framework for Considering Values

An initial approach to technology is to take into account its etymology. In this regard, the term “technology” is a kind of knowledge, insofar as it is the logos (the doctrine or learning) of the techné (Cf. Mitcham 1980). But “techné” might be in the realm of “arts,” when the main aim is to create beautiful objects, or in the sphere of “technics,” when this human activity seeks to build up useful items. Techné is a practical activity based on knowledge of experiences of the past and the present, which follows certain rules to get artistic products or to produce tools for useful purposes.

Historically, technology appears as a social activity based on qualified knowledge, which is commonly developed in an intersubjective doing that achieves specific aims. But this human contribution to society goes beyond techné in many ways, among them three: (i) the kind of knowledge used (scientific as well as specific of technology), (ii) the complexity of the human undertaking developed (essentially creative in order to achieve an actual innovation), and (iii) the characteristics of the product obtained as a consequence of the undertaking (frequently, a new artifact that may have a officially registered patent).

Certainly the kind of knowledge used in technology is different from technics, due to the sophisticated aims to be achieved and the variety of values involved in the selection of the designs. Technology is a human undertaking that has higher aims than mere technics, because technology is oriented towards the creative transformation of the previous reality (natural, social, or artificial) using scientific knowledge as well as specific technological knowledge. This transformative process follows values when technology builds up a product that should be tangible. The product might be a noticeable change of nature (e.g., a tunnel), a new kind of social reality (e.g., a new social order in a country) or a visible artifact (e.g., an aircraft). Ordinarily, when the final product of technology is an artifact, it might be registered in a patent.Footnote 4 This could hardly be the case in the final outcome of a technics or when a science is developed (included applied science).Footnote 5

Following this analysis, it seems clear that technology is more than knowledge used in a transformative way to get a final product or artifact. I consider that “technology” includes a variety of components. (1) It has its own language, due to its attention to internal constituents of the process (design, effectiveness, efficiency, etc.) and external factors (social, ecological, aesthetical, cultural, political, etc.). (2) The structure of technological systems is articulated on the basis of its operativity, because technology should guide the creative activity of the human being that transforms nature, social reality, or artificial items. (3) The specific knowledge of the technological undertaking—know-how—is instrumental and innovative: this kind of knowledge seeks to intervene in an actual realm, to dominate it and to employ it in order to serve human agents and society. (4) The method used is based on an imperative-hypothetical argumentation.Footnote 6 Consequently, the aims are the key to making reasonable or rejecting the means used by technological processes.

(5) There are values regarding the aims chosen and accompanying the technological processes. These values could be internal (such as realizing the goal at the lowest possible cost) and external (social, political, ecological, etc.). They establish the conditions of viability of the possible technology and its alternatives. (6) The reality itself of the technological process is supported by social human actions, which are based on intentionality oriented towards the transformation of the surrounding reality.Footnote 7 (7) There are ethical values endogenous to technology, insofar as it is a free human activity, and there are also exogenous values to the aims, processes, and results of technology, because this is a human undertaking developed in a social milieu.

Hence, technology can be seen as a human activity oriented to obtain a creative and transformative domain of that reality—natural, social, or artificial—on which it is working. Primarily, technology does not seek to describe or to explain reality, because there is already a discovered reality, which is known to some extent (and its future can be predicted),Footnote 8 that technology wants to change according to certain aims. This technological domain appears at least in new designs and in the effectiveness-efficiency couple. Furthermore, it requires us to consider other aspects related to this human activity (ethical, economic, ecological, aesthetical, political, cultural, etc.).

Consequently, values play a role here. In one way or another, they point out what is worthy, or what has merit for us, either in objective terms, subjective terms (as individuals) or intersubjective terms (as a group or as a society). Thus, it might be the case that a technology could achieve its aims as such (i.e., effectiveness), but that we may consider it as non-acceptable from the point of view of other factors. Some values might be at stake here. They may be connected to economic criteria (e.g., the cost-benefit ratio), ethical principles (e.g., consent, fairness), aesthetical evaluations (e.g., beauty, harmony),Footnote 9 ecological effects (e.g., absence of pollution in the air or lack contamination of the rivers), political consequences (e.g., the civil liberties, the social progress) or repercussions for the dominant culture (e.g., in terms of compatibility regarding the shared criteria).

Meanwhile, the framework for considering values might be in the sphere of “technoscience.”Footnote 10 But this term has been understood until now in rather different ways. (a) Technoscience is a new word that represents the identity between science and technology.Footnote 11 (b) Technoscience is an expression compatible with “science” and “technology,” insofar as it expresses the sense of a strong practical interaction between science and technology while maintaining the difference in their references.Footnote 12 (c) Technoscience is the term for a new reality, a kind of blend or hybrid of science and technology.Footnote 13 (d) Technoscience could be just “techno-logos” or “techno-logic.” This indicates that it is a subject that can be understood as directly based in science.Footnote 14

Technoscience as identity between science and technology—the first option—includes that they have been strengthening their ties, and science and technology have got to the point where there are no semantic differences between both. In addition, they also have a common reference because there are no longer ontological differences between them. According to the practical interaction—the second position—the reference of technoscience is then twofold: there are two different aspects of reality that can have a causal interaction (or, at least, there is a relation which preserves the ontologies of science and technology).

Along with the hybrid position—the third view on technoscience—the referent has properties that are different from science and technology.Footnote 15 In this case, the three of them can coexist (science and technology as well as technoscience). But technoscience understood as “techno-logos” or “techno-logic”—the fourth possibility—makes no sense for defining “technoscience:” the difference between “technics” and “technology” lies mainly in this point. Technics is practical knowledge of an accumulative kind, based on human experience but without the support of an explicit scientific knowledge; whereas technology is a human activity which transforms the reality (natural, social, or artificial) in a creative way, and it does so precisely on the basis of aims designed with the assistance of scientific knowledge (as well as by means of specific technological knowledge).

Conceptually, technology and science can be seen as different, even though they are heavily interwoven in many cases (primarily technology based on natural sciences, such as naval or aerospace technologies).Footnote 16 These conceptual differences can be noticed if science and technology are conceived around some constitutive elements, which include semantic, logical, epistemological, methodological, ontological, axiological, and ethical components.Footnote 17

Sensu stricto, following those components, there is no genuine identity between science and technology. Thus, we can consider the theoretical reasons as well as the practical aspects to point out ontological differences between science and technology (cf. Niiniluoto 1997a, pp. 285–299; especially, pp. 287–291). This dissimilarity also involves a methodological distinction between scientific progress and technological innovation, even though this recognition is compatible with the acceptance of frequent cases of a strong practical interaction between science and technology (cf. Gonzalez 1997). These cases might be grounds to emphasize the use of the term “technoscience.” But the existence of a causal interaction between science and technology should avoid two possible interpretations: the reduction of technology to a mere applied science, or the conception of science as a simple kind of by-product of technology.

Values in the Structural Dimension

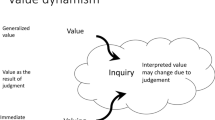

Concerning the role of values in technology, the focus might initially be on the framework oriented towards the structural dimension or be led by the dynamic perspective. In the first case, the role of values is related to the configuration of technology itself, i.e., values that belong to this social construction, which is different from other human activities (philosophy, science, arts, etc.). This analysis of the structural dimension involves taking into account a set of aspects, three of which are: (i) technology as a human knowledge, (ii) technology as a social undertaking oriented towards the creative transformation of reality; and (iii) technology as a product or artifact.

Unquestionably, technology is a human knowledge that needs to choose aims. This selection is made in order to develop processes that are oriented towards the achievement of concrete results. In this regard, the knowledge that (“descriptive”), the knowledge how (“operative”) and the knowledge whether (“evaluative”) are involved. In effect, technology requires some scientific knowledge, a specific technological knowledge (mainly concerning the artifacts), and the knowledge about what is preferable instead of that merely preferred. The latter is the sphere of values, which is related to evaluative rationality.Footnote 18 In this sphere of knowledge, values have a role related to the technological designs and the methodology used to developed such designs (e.g., economic values have a role in both steps) (cf. Gonzalez 1999a).

After technology as human knowledge, there is a more noticeable aspect for society: technology as a human undertaking developed in a social setting. This is a key feature in the comparison with science, because technology creatively transforms the reality. Thus, things are different when this human undertaking intervenes in nature, in society, or in the artificial world, because a new reality is eventually available (a tunnel, a bridge, an aircraft, a computer, a mobile phone, etc.). This aspect is also connected with instrumental rationality, which is a key factor in technology. In this practical realm, the role of values is mainly focused on means to achieve aims (which is commonly related to values such as effectiveness and efficiency). The values may also be economic (e.g., profitability in terms of cost-benefit). In addition, a set of values can be taken into account: ethical, ecological, aesthetical, sociological, cultural, political, etc.

Commonly, for the citizens, the most tangible aspect of technology is the product or artifact. Technology is, then, the reality available after the transformation of some elements of the world (natural, social, or artificial). Here again a set of values is involved. Some of them are related to the item itself that is available. In this regard, first, certain values might be purely instrumental or operative, such as utility; and, second, there is room for many additional values (aesthetic, cultural, sociological, etc.) in a product or artifact. These values are connected to the setting of such item, which is always historical. They might be of quite different kinds: social, economic, political, cultural, etc. Frequently, the technological product or artifact is registered in an official patent, which is used as a guarantee for its economic value for markets and organizations.Footnote 19

Each of these three important approaches to technology—as knowledge, human undertaking, and product or artifact—involves two main categories of values according to its status: “internal” and “external.” On the one hand, there are some values that are endogenous to the designs, processes, and results of the technology that is developed (effectiveness, efficiency, etc.); and, on the other, there exists some values that are exogenous to the contents of the technology as such, and these contextual values (ecological, social, cultural, political, etc.) complete the picture of the structural configuration of technology.

According to this analysis, when technology is seen in a structural dimension, there is a role for internal values and a role for external values. Their relation cannot be considered in terms of a rigid frontier or an axiological wall but rather as an interaction of values within a framework of holism of values. They can be considered as a sort of system where there is an interrelation between both sides, internal and external. Thus, although some values are mainly “internal” whereas other are mostly “external,” there is a kind of osmosis between them. Both flanks of values require to taking into account that technology is not only structural but also dynamic.

Values in the Dynamic Perspective

Undoubtedly, there is a dynamic perspective regarding the role of values in technology. On the one hand, insofar as technology is a creative transformation of reality, it is always a dynamic enterprise. The set of aims, processes, and results (products or artifacts) sought by technology belong to a dynamic framework. On the other hand, innovation is a crucial factor for any technology. Commonly, an outdated technology is replaced by an innovative technology. Sometimes it precedes the actual demands of the users for the new products (see, in this regard, the innovative approach to information and communication technologies led by Steve Jobs) [cf. Isaacson 2011, passim; especially, pp. xx–xxi and 565–566].

Innovation is a characteristic feature of technology as such, and it might be in the aims, in the processes, or in the results of a specific technology (cf. Gonzalez 2013c). Hence, innovation can appear in the technological designs, in the human undertaking of making a technology, and in the final products of artifacts obtained. This innovation is always made according to some values, either internal or external. To be sure, the improvements of a technology can be based on endogenous technological values, such as effectiveness or efficiency, or can be built up on exogenous technological values (aesthetical, social, ecological, cultural, political, etc.).Footnote 20

Both kinds of values—internal and external—have a role in the dynamic perspective on technology insofar as it is a human undertaking, and this trait requires the performance of agents seeking some aims. Thus, these are values related to technology as a historical activity that is due to agents with specific purposes. “Historical” is used here in a deep sense, connected to human beings and societies, which goes beyond the mere chronological dimension to embrace the possibility of radical changes, in addition to gradual changes or piecemeal modifications. Consequently, the technological variation can be richer than an “evolution,” understood in terms of mere adaptation, in order to take in an actual facet of “historicity” in technology.Footnote 21 Therefore, it is open to the possibility of revolutionary changes, which can be recognized in some technological innovations (of which the Internet is one).

Historicity of technology is compatible with values seen in dynamic terms. Values can have at least a dual role in dynamic terms: on the one hand, they influence the technological changes in the three levels pointed out (in technology in general, in specific versions of it, and in the agents that build it up); and, on the other, the values themselves can be different over time, because of the emergence of new values, the modification of previous values, or the obsolescence of some values. Thus, besides the dynamic role on the technology (as knowledge, human undertaking, and product or artifact), there is another trait to be considered here: the change itself of the values related to technology.

How is this change of values possible? From the point of view of technology in general and specific forms of technology, it seems clear that there are novelties—above all, new realities—that are introduced by technology, mainly in some specific branches. These novelties can change the values accepted in a particular society. This has been the case with information and communication technologies (ICTs), because the Internet and the world wide web have oriented new values, internal as well as external. This change of values is based on new demands in public life, which is a combination of cultural elements (those constructed by human beings in a society) and natural traits (those grounded on what humans received). These aspects might give an account of the possibility of having historicity and objectivity of values regarding technology, in general, and in ICTs, in particular.

Regarding this issue of the variation of the values concerning technology, it seems clear that there are two main possibilities in novelty: a change “from within” and a modification “from outside.” On the one hand, there might be an “internal” variation in technology, i.e., a change regarding the technological values already known. This possibility of variation can be considered in terms of new priorities or prestige of some values (such as ecological values for oil platforms, aesthetic values on phones and computers, or social values regarding roles in order to develop domotics) or the diminishing influence of the previous values, i.e., a minor consideration of something previously evaluated as worthy (such as the value of efficiency by all means, including what affects the protection of the natural environment). On the other hand, some values may arise due to the factor of novelty connected to the “external” context of historicity: human society is, by definition, historical and innovation leads to new technological realities, such as smart phones or tablets.

But the change of values should be seen from the angle of the agents. Regarding values in general, there are at least two large possibilities available from such a perspective: (1) values based on human needs, which commonly involve stability (and, in some cases, there might even be invariants); and (2) values based on optional factors of human life, which in principle include variation, insofar as they depend on the degree of acceptance. The variation might be connected to time factors (such as a generational change) or other aspects (cultural, social, etc.).

First, values based on human needs, which make them strong, because the human needs give the values a solid ground, a place where is possible put down roots. There is then a support for the objectivity of those values,Footnote 22 a bedrock that is different from the subjective preferences or the intersubjective options of a community (either a small group or society as a whole). These values are those that basically remain the same over time, with some possible improvements due to an increase in the level of sophistication (e.g., related to clothing, housing, bridges, etc.).

Second, there are values based on optional factors of human life, which are related to the diversity of aspects of the life of persons and societies. This second kind of values may involve historicity in its content: (a) these human values are not Platonic entities to be shared by ontological participation; and (b) values are considered worthy according to some criteria (preferred, preferable, etc.), and their acceptance involves that they hold some merit. In this regard, the things considered as worthy by human agents can change from time to time (e.g., from a generation to the next) and even from one individual to another.

Once both possibilities of the agents are considered—values based on human needs and on optional factors—it seems to me that they can be used for the case of values regarding technology. Thus, there is a reason to think of the stability with some improvements in certain technologies (i.e., the refinements of current ones) and the clear variation of other specific technologies (i.e., the innovative new products).Footnote 23 The recognition of the existence of a historicity in the values does not involve eo ipso a relativism of a historical kind:

(I) The change in the values themselves or the variation in the level of acceptance of some values is commonly gradual or piecemeal instead of being instantaneous or fast. Thus, the change takes some time (e.g., ecological values). (II) There are few revolutionary changes of values, if we see them as holistic and in a very short period of time. They might happen after natural disasters or huge technological failures and, then, there is some objective basis for the changes of values (e.g., security). (III) The exogenous values usually require some intersubjective acceptance. Consequently, the content of values is frequently shared by a number of agents rather than by a single individual or small community.

Axiology of Technology

Subsequent to the acceptance of the presence of values in technology, both in the structural dimension and the dynamic perspective, the issue is then the roots of these values. The analysis can be made through axiology of technology, which is the philosophical study of values about technology (internal as well as external). This analysis can consider the “descriptive” aspect of values (which involves the recognition of the values actually used in technology) and the “prescriptive” facet on them (which implies that there are values that should have a leading role).Footnote 24

Any axiological study should consider both sides, descriptive and prescriptive. Thus, axiology of technology should be dual in its initial focus, analyzing which values are actually in place in contemporary technology, and what ought to be done according to the accepted values. Commonly, when the analysis is made on values in general, instead of being focused specifically on ethical values, the philosophical study pays more attention to the “descriptive” aspect than to the “prescriptive” facet.

Prima facie, there are three possible levels of philosophical analysis about how this technological realm is built up: general, specific, and related to the agents. (i) Axiology of technology in general considers those values that can be in any form of technological expression. (ii) Axiology of a specific technology studies those values that belong directly to a concrete expression of technology: naval, aerospatial, mines, informative and communicative, electronic, etc. (iii) Axiology of the agents developing technology takes into account the values that are accepted by those that prepare the designs, choose the processes, and evaluate the results.

Even though the levels of axiology of technology in general and axiology of the agents developing technology are different, there is an interaction between them. Moreover, a source of innovation in technology comes from the interest of the agents in novelty. This might involve dissimilar or even diverse values between the standard technological values and the new values that come from creative agents, and they can lead to actual innovations. On the one hand, this can change the traditional conception of technology, commonly attached to “impersonal” or “abstract” values (effectiveness, efficiency, etc.), to a vision closer to human values of our undertaking (i.e., technology as our technology); and, on the other, the relevant technological innovations introduced by some agents, such as Steve Jobs, can bring about new values (e.g., new social and cultural values) in addition to economic values.Footnote 25

However, there is a second kind of approach to axiology of technology, which is in place when the focus is on the use of technology instead of on how technology is built up. Thus, there is a distinction to be made between the construction of a technology and the application of a technology.Footnote 26 One thing is technology as a human enterprise characterized by the constitutive elements pointed out already (language, system, knowledge, method, social undertaking, etc.), which commonly emphasizes three main aspects (the knowledge connected with the designs, the processes used to carried out them, and the products or artifacts obtained). Another thing is the use of technology in a variable setting, which is the practice of engineers or architects. This application is commonly developed in private organizations and public institutions. In this regard, it seems clear that, based on the same technology (i.e., the contents given by academic institutions), the practice of technology can vary from one person to another and from one place to another (even within the same city).

Through the practice of using technology some new values can be added. This is the ordinary case, because engineering or architecture are human activities developed in a social setting, within a historical context and economic support. Thus, the accepted values of the profession in engineering or architecture might be different according to cultural or historical factors. These contextual values can be quite diverse depending on the standards accepted in each society and the traditions of that professional community. Moreover, these aspects related to external values include some problems connected with the private organizations and public institutions that give economic support to the projects of engineers or architects.

The Role of “Internal” Values in Technology

Internal values are those that belong directly to technology itself or a specific technology (e.g., information technology), such as values regarding the design, the processes, and the results. They contribute directly to what technology is and ought to be. The values are “internal” insofar as they are endogenous for any technology or a particular version of it. Thus, they might be crucial for the possibility, operativity, and availability of a technology (communicative, naval, spatial, industrial, civil, mines, etc.). In addition, these values are commonly considered by the agents that build up technology. Thus, they can appear in the three axiological levels pointed out (general, specific, and agents).

At the same time, there are “external” values to technology. These are around the central technological factors already mentioned (aims, processes, and results), which are immediately connected with the constitutive elements of a technology (language, system, knowledge, methods, undertaking, etc). Thus, these values are exogenous insofar as they are related to the context of technology, such as the legal, social, cultural, political, ecological, or aesthetical aspects. But these external values to technology are also relevant, because they deal with what is worthy in many ways and what receives the attention of citizens, groups, societies, etc.

In principle, external values accompany internal values both for the structural dimension of technology and the dynamic perspective of technology. They are relevant for the configuration of technology as well as for its change over time. Due to its dynamic contribution, external values are open to possible changes. Thus, it is feasible that some of them might end up being “endogenous.” This change occurs when an initially external value (such as the ecological value or the aesthetic value) become decisive for the design of technology (e.g., in technologies developed for protected areas of the world, such as Antartica, or in new smartphones, in order to have a more competitive design).

Likewise, there are values that can have an internal role as well as an external role. This is what happens with economic values (cf. Gonzalez 1999a). (i) They might be internal insofar as they intervene in the design and the methods. On the one hand, there are undeniable connections between the technological designs and the economist costs. Thus, technological knowledge requires considering economic values. And, on the other hand, these links affect the technological procedures, which need to consider the economic factors. (ii) Economic values can have an external role. Their presence is indisputable in the sphere of technology as human undertaking (e.g., wages to be paid, instruments to be used, business firms needed, etc.). But economic values also have a role in the sphere of technological policy, because they are considered in the decision-making of private organizations and public institutions (governments, international committees, etc.).Footnote 27

The Task of “External” Values in Technology

Initially, there is a large number of “external” values related to technology: aesthetic, social, cultural, political, legal, economic, ecological, etc. Certainly, the aims, processes and results of technology have tangible consequences for the citizens, markets and organizations. The reason is clear: technology is oriented towards the creative transformation of the reality. Thus, its design looks to change existing reality (natural, social, or artificial) to produce new results. When the product is an artifact (airplane, automobile, computer, cell phone, tablet, etc.), the lives of the members of society can be directly affected. These changes might favor social development or they may be against the common good of citizens.Footnote 28

External values can have a role in the three main stages of the technological doing. (1) They can intervene in the design, because technology uses scientific knowledge (know that), specific technological knowledge (know how), and evaluative knowledge (know whether). Thus, technology can take into account exogenous values (social, economic, ecological, etc.) in the design. This “external” task is clear in many technological innovations (smartphones, tablets, large airplanes, etc.), because they should consider the users of the product and the potential economic profitability of the new artifact. (2) The technological processes are developed in public or private enterprises, which are organized socially according to some values (economic, cultural, political, etc.) and with an institutional structure (owners, administrators, etc.) (3) The final result of technology is a human-made product (commonly, an artifact) to be used by society, and it has ordinarily an economic evaluation in markets and organizations (cf. Gonzalez 2005b, 27–32).

Thus, insofar as technology is ontologically social as a human doing, it can be evaluated according to values accepted in the society. Furthermore, its product is commonly an item for society (even in the case of technology regarding nature, such as in the case of a tunnel). Moreover, the criteria of society have a considerable influence in promoting some kind of technological innovations (with their patents) or an alternative technology (with a new design, processes and product). Frequently, from the perspective of external values, technology is viewed with concern, especially in the case of recent phenomena (e.g., in accidents related to nuclear energy, the use of biotechnology with human beings, the nanotechnological risks, or in the dangers of new technologies such as hydraulic fracturing or “fracking”).

These external values are very influential in the reflection on the limits of technology, when philosophy asks for the bounds (Grenzen) or ceiling of technology. This analysis of the terminal limits of technology should take into account the internal values as well as the external values (social, cultural, political, ecological, aesthetic, economic, etc.). In this regard, philosophy of technology considers the external values in the context of a democratic society interested in the well-being of its citizens,Footnote 29 thinking that their members can contribute to decision making (e.g., by means of associations or through the members of the parliament). The study of the limits of technology include the prediction of what technology can achieve in the future, but also require the prescription of what should be done according to certain values.Footnote 30 This prescriptive dimension of the external values of technology is more noticeable with there are clear risks for society at stake, either for the present or for the future (cf. Rescher 1983; Shrader-Frechette 1985, 1991, 1993).

Frequently, behind the analysis of values in technology, there are some influential philosophical orientations regarding what technology is and ought to be. Two of them seem to be especially important in the processes in technology and its results: (I) technological determinism, which assumes that the development of technology is uniquely determined by internal laws; and (II) technological voluntarism, which maintains that the change can be externally directed and regulated by the free choice of the members of the society. Both conceptions are related to the actual level of autonomy of human beings while doing technology.

On the one hand, technological determinists can argue that the development of technology—in general, and of a particular one—is de facto a complex system process where the imperatives have a role (at least, methodologically). On the other hand, technological voluntarists can point out that the citizens do not have to obey eo ipso those imperatives. Ilkka Niiniluoto suggests an interesting middle ground between “determinism” and “voluntarism:” the commands of technology are always conditional, because they are based on some value premises. Thus, it is correct that we do not have to obey technological imperatives. Therefore, the principle that “can implies ought” is not valid insofar as not all technological possibilities should be actualized (cf. Niiniluoto 1990). Values should have a clear role here in decision-making regarding technology, which includes particular importance for the characterization of a “sustainable development” based on technology.Footnote 31

Ethics of Technology

Among human values are the ethical ones. They belong to the core of ethics of technology, which deals with this human entreprise insofar as it is a free human activity. This involves a common distinction between “ethics” and “morals.” Philosophically, ethics is related to the justification of human activity, according to some norms that can be based on principles that might have a universal form. Thus, there are important ethical systems throughout the history of philosophy (among them, the Aristotelian and Kantian proposals). Meanwhile, morals is conceived as the study of the actual way of behavior of individuals, groups and societies, trying to make explicit the rules and norms that they used de facto in one way or another.

When the focus of attention is on ethics, the philosophical study is more relevant insofar as it seeks a universal form or, at least, the widest level of generality. Obviously, there are many philosophical questions about technology and ethics that are relevant. Kristin Shrader-Frechette considers that they “generally fall into one of at least five categories. These are (1) conceptual or metaethical questions; (2) general normative questions; (3) particular normative questions about specific technologies; (4) questions about the ethical consequences of technological developments; and (5) questions about the ethical justifiability of various methods of technology assessment.” (Shrader-Frechette 1997, p. 26).

Shrader-Frechette gives examples along these lines: (i) how ought one to characterize “free, informed consent” to risks imposed by a sophisticated technology?; (ii) are there duties to future generations potentially harmed by a technology?; (iii) should the US continue to export banned pesticides to other nations?; (iv) would development of a nuclear based energy (plutonium) technology threaten civil liberties?; and (v) does the benefit-cost economic analysis ignore noneconomic components of human welfare? It seems to me that here, again, there is the possibility of distinguishing three levels of analysis: general, specific, and related to the agents.

(a) Ethics of technology in general deals with those aspects that are relevant for any kind of technological enterprise. (b) Ethics of a specific technology takes care of the ethical problems in a concrete domain, such as the ethical issues of informative and communicative technologies (for example, in the case of the Internet or the social networks of the web). (c) Ethics related to the technological agents considers the ethical values used by them as criteria of what is worthy, as well as what they think ought to be done when they make designs, develop processes, and obtain results (product or artifacts). In this regard, the analysis goes beyond the mere morals of the technological agents (what they actually do nowadays) in order to offer an ethical proposal of what should these professionals do today and in the future.

Again there are two sides to the philosophical analysis of technology: the endogenous perspective and the exogenous viewpoint. The endogenous ethics of technology analyzes the steps of this free human entreprise, such as knowledge, human undertaking, and product or artifact. Meanwhile, the exogenous ethics of technology evaluates the contextual aspects of this human activity carried out in a social milieu. Thus, it takes into account ethical values socially assumed or institutionally accepted, which includes legislation at the different levels (regional, national and international) insofar as laws are embedded of ethical values.

The Endogenous Perspective on Ethics of Technology

As regards this endogenous perspective, it deals with the aims, the processes, and the results searched in technology. It is important do not think, in principle, of ethical values in mere terms of consequences but rather in terms of the ethical legitimacy.Footnote 32 Furthermore, the analysis cannot be made merely according to the legal standards in a country, because any ethical consideration of technology goes beyond such criteria. Thus, nobody can seriously consider as ethical some technologies that were commonly accepted in the past. Among them are machines and processes used in factories that were totally unhealthy due to the high level of pollution produced, even though those machines and processes of the factories were legal in many countries for years (and even now we can see examples of this phenomenon in several parts of the world).

Endogenous ethics of technology can start with knowledge insofar as it is not a mere “content” but rather an element of a human activity.Footnote 33 Initially, human knowledge as such—a cognitive or epistemic content—cannot be evaluated ethically (cf. Rescher 1999, pp. 159–162). However, knowledge in technology involves several aspects (scientific, specific of artifacts, and evaluative) that can be connected with the human undertaking of creative transformation of the reality. In this regard, knowledge in technology can be a part of a human free activity, and so it can be considered within an ethical setting. Moreover, knowledge is used for establishing the aims of the design, and these might be ethically acceptable or unacceptable.

Therefore, endogenous ethics can consider technology as a human undertaking that transforms reality (natural, social, or artificial). This social activity is, in principle, free in the original making (i.e., the innovative phase of creation of the technology) as well as in the practical used (i.e., the application to actual purposes by individuals or groups). Thus, the aims, processes, and results of this human activity of technology can be evaluated in ethical terms (i.e., the good and the bad, the right and the wrong, the correct and the incorrect, etc.).

Clearly, this is also the case in the use of technological expertise by engineers and architects,Footnote 34 whose moral performance can be ethically evaluated. In this regard, the single-minded solutions to technological problems should be avoided. Consequently, the ethical criteria can be considered for the possible technological alternatives, because there are commonly one or more technological alternatives to the technological undertaking in use. Those who use technology—mainly, engineers and architects—need to consider that ethics is endogenous to technological doing (mainly, because of the ethical evaluation of means and ends) and, therefore, ethics is not just exogenous (due to social or cultural pressure) to technology.

If the ethical evaluation of the human undertaking of technology is undeniable, due to the relevance of the characteristics of this free social activity (especially for the human person and the society as a whole), the presence of ethical values regarding the product or artifact might be clear as well. Sometimes the ethical evaluation can regard the artifact itself (e.g., a chemical weapon or a nuclear bomb), whereas in other cases the values of ethics can be focused on the use of the technological product or artifact. In this regard, there are several options, which includes the dual possibility: in some cases the utilization of a product might be good for the society, whereas in other cases the employment of that product might be harmful or noxious. This is what happens with some technological artifacts used in medicine.

The Exogenous Viewpoint of Ethics of Technology

Exogenous ethics has a role from the beginning insofar as technology is a human undertaking related to other human activities within a social setting. Technology is our technology in its structural dimension as well as in its dynamic perspective: it is a knowledge, an undertaking, and a product of human beings in society. (i) From the viewpoint of structure, the realm of technology are persons and groups willing to transform nature, society, or artifacts for social purposes, which might be ethically acceptable for that concrete milieu or unacceptable. (ii) Within the dynamic perspective, the exogenous values of ethical character in technology come under the influence of historicity: each historical period has variations in the evaluation of knowledge, undertaking, and product of human beings in society.

Given the relevance of the changes introduced by the technological transformations, the ethical criteria can be used in cases such as the “precautionary principle”—mainly, related to a reasonable sustainable development—Footnote 35 and other ethical contents assumed by laws (regional, national, and international). Thus, the ethical values might be important at different levels of society, and they have consequences for the developing countries. At the same time, the existence of a globalization involves that dynamic changes in technology are more intense than in the past. Private organizations (business firms, corporations, etc.) and public institutions are under regulatory conditions that should have ethical bases, such as preservation of environment, respect for people, avoidance of damage to the communities, etc.

Throughout the intense discussion on risks, where the exogenous ethical values of technology have a strong role, the existence of a variability from one country to another and from one historical moment to another seems clear. These ethical values—in the exogenous perspective—can be diverse depending on the ethical standards of each society, which includes the problems connected with public morality. Again, it affects the kind of technology accepted in a society, the specific forms of technology that might be considered at least as harmless, and the type of ethical principles accepted by the community of agents that build up a technology in a historical context.Footnote 36

Here also appears the other side of the exogenous ethics: how society, when it is embedded in technology, can shape the agents that develop new technologies? Is the technology itself a source of ethical values? Regarding this issue, Carl Mitcham points out two options: “what might be termed substantivism is the position that technological change strongly shapes or influences social, political or human affairs; (…) as technology globalizes, socio-cultural orders converge. By contrast, instrumentalism views artifacts as tools that can reflect and be used in many different ways by diversity of human lifeworlds. (…) People shape their lifes and cultures, then as individual or groups incorporate and adapt technologies in whatever ways they choose” (Mitcham and Waelbers 2009, p. 371).

The type of relation here may be two-way: on the one hand, technological innovation changes society (e.g., knowledge society under the influence of the Internet and the world wide web is clearly different from the society in the times of Great Depression), and these changes also shape ethical values (e.g., privacy, responsibility, solidarity, etc.); and, on the other hand, technology is completely human made (in its designs, in its undertakings, and its products), and its contents show a style of life chosen according to some social objectives. The assumption of the first direction makes the use of some criteria, such as utility, understood as an ethical principle for our society; but the relevance of the second direction emphasizes the role of human freedom regarding those tools that have been made in a society. Aims, processes, and results of technology are based on human decisions in a social setting.Footnote 37

All in all, values have an important role for the structure of technology and for its dynamics over time. Internal values and external values are relevant for the designs, undertakings and products. Both sides—internal and external—are needed in order to clarify the values on which technology is built up and ought to be developed. Its configuration and historical dynamics depends on values.Footnote 38 Among these values, ethical ones have a very important role, both from an endogenous perspective and exogenous viewpoint. Ethical values can be considered in the knowledge, undertaking and products of technology. In addition, it seems clear that they have a role regarding aims, processes and results of this human activity. In this regard, society has the right to expect reasonable ethics of technology, and it should seek a rational technological policy for its citizens.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

To some extent, there is a similitude between this variation and the explicit change in the case of science. Cf. Gonzalez (2013a).

- 4.

The issue of the registration and used of patents has important practical consequences. See in this regard Wen and Yang (2010).

- 5.

Usually, the outcomes of science are public and of free access to users. However, the characteristic products of technology can be patented and, therefore, be initially private and with no free access for users.

- 6.

This imperative-hypothetical argumentation is different from the kind of argumentations commonly used in science, such as the hypothetical-deductive or the inductive-probabilistic.

In technology, if the aim is accepted, then the means and costs should be considered. If the means can guarantee the achievement of the aim—in a finite number of steps—and the estimated costs seem reasonable, then these means should be used to obtain the chosen objective, otherwise the “instrumental rationality,” which is central in technology, does not work in this case. The “imperative” component—focused on the means that should be used—in technological argumentation comes after the acceptance of the hypothetical aims, means, and costs.

- 7.

These components are considered in Gonzalez (2005b), pp. 3–49; especially, p. 12.

- 8.

It is interesting the existence of institutions that explicitly supports a direct connection between technology and future. This is the case of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, which has a “Hillman Center for Future-Generations Technologies.”

- 9.

A notorious example of the search of the combination of art and technology is Steve Jobs. He was the cofounder of Apple, the founder of NeXT and the chairman of Pixar. He insisted in connecting aesthetical values and sophisticated technological procedures. Cf. Isaacson (2011), pp. 238–249, especially, pp. 239, 244 and 248.

- 10.

- 11.

This option is considered and criticized by Ilkka Niiniluoto, cf. Niiniluoto (1997a).

- 12.

- 13.

- 14.

The analysis follows here Gonzalez (2005b), p. 9.

- 15.

Technoscience understood as “hybridrization” or “symbiosis of science and technology” suggests examples, such as the interaction of the computer sciences and the information and communication technologies, which lead to products popularly called “new technologies,” where the patents are on properties different from those obtained by previous technologies. See Echeverria (2003), pp. 64–68 and 71–72.

- 16.

- 17.

See, in this regard, Gonzalez (2005b), pp. 3–49; especially, pp. 8–13.

- 18.

- 19.

On the difference between “markets” and “organizations,” see Simon (2001).

- 20.

According to Steve Jobs, “you can’t win on innovation unless you have a way to communicate to customers,” Isaacson (2011), p. 369.

- 21.

On the distinction on “process,” “evolution,” and “historicity,” see Gonzalez (2013b).

- 22.

A relevant analysis of the objectivity of values is in Rescher (1999), ch. 3, pp. 73–96.

- 23.

On this issue, see section 3 “The Role of Innovation in Technology” in Gonzalez 2013c,pp. 19–24.

- 24.

An interesting reflection can be made on the role of “technological imperatives,” cf. Niiniluoto (1990).

- 25.

According to Walter Isaacson, Jobs “knew that the best way to create value in the twenty-first century was to connect creativity with technology, so he built a company where leaps of the imagination were combined with remarkable feats of engineering. He and his colleagues at Apple were able to think differently: They developed not merely modest product advances based on focus groups, but the whole new devices and services that consumers did not yet know they needed,” Isaacson (2011), p. xxi.

- 26.

This distinction between construction and application can be seen in science: applied science is not the same as application of science. Cf. Niiniluoto (1993) and Niiniluoto (1995).

When applied science is developed, the aim is the solution to specific problems in a concrete realm of reality, whereas application of science is the use of that knowledge in a variable setting. Thus, using the same applied science, the applications of the available knowledge can be clearly different (for example, in hospitals).

- 27.

Commonly, this leads to legal aspects (international, national, and regional). In this regard, the precautionary principle has been discussed in many ways, as can be seen in the final bibliography of this chapter. Cf. D’Souza and Taghian (2010); Stirling (2006); and World Commission on the Ethics of Scientific Knowledge and Technology (2005).

- 28.

- 29.

- 30.

Prescription is attached to an evaluation and an assessment of the good and bad for society of the decision. This is a common practice in applied sciences such as economics, cf. Gonzalez (1998b).

- 31.

- 32.

- 33.

This is also the case in science, cf. Gonzalez (1999b).

- 34.

See in this regard Neely and Luegenbiehl (2008).

- 35.

- 36.

- 37.

From the internal point of view, the methodology of technology has a central role. It is based on an imperative-hypothetical argumentation, where the aims are crucial to making reasonable or to rejecting the means used by the process of developing a technological artifact. And, from an external perspective, technology requires social values as human undertaking: the technological processes cannot be beyond social control.

- 38.

Historicity is important regarding some values in technology. The historical dynamics of technology requires to consider the evolutionary changes (the improvements in off-shore platforms, aircrafts, automobiles, …) and the “technological revolutions” (such as the computers). An analysis of the second ones is in Simon (1987/1997).

Bibliography

Achterhuis, H. (ed.). 2001. American philosophy of technology: The empirical turn. Translated by Robert Crease. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Adner, R., and R. Kapoor. 2010. Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strategic Management Journal 31(3): 306–333.

Agassi, J. 1980. Between science and technology. Philosophy of Science 47: 82–99.

Agassi, J. 1982. How technology aids and impedes the growth of science. Proceedings of the Philosophy of Science Association 2: 585–597.

Agassi, J. 1985. Technology. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Agazzi, E. 1992. Il bene, il male e la scienza. Le dimensioni etiche dell’impresa scientifico-tecnologica. Milan: Rusconi.

Annavarjula, M., and R. Mohan. 2009. Impact of technological innovation capabilities on the market value of firms. Journal of Information and Knowledge Management 8(3): 241–250.

Aven, T. 2006. On the precautionary principle in the context of different perspectives on risk. Risk Management 8(3): 192–205.

Becher, G. (ed.). 1995. Evaluation of technology policy programmes in Germany. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Berger, P.L., and T. Luckman. 1967. The social construction of reality. New York: Doubleday-Anchor.

Beyleveld, D., and R. Brownsword. 2012. Emerging technologies, extreme uncertainty, and the principle of rational precautionary reasoning. Law, Innovation and Technology 4(1): 35–65.

Bijker, W.E. 1994. Of bicycles, bakelites, and bulbs: Toward a theory of sociotechnical change. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Bijker, W.E., and J. Law. 1992. Shaping technology/building society: Studies in sociotechnical change. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Bijker, W.E., T.P. Huges, and T. Pinch. 1987. The social construction of technological systems: New directions in the sociology and history of technology. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Borgmann, A. 1984. Technology and the character of contemporary life: A philosophical inquiry. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Borgmann, A. 1999. Holding on to reality: The nature of information at the turn of the millennium. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bronson, K. 2012. Technology and values—Or technological values? Science and Culture 21(4): 601–606.

Bugliarello, G., and D.B. Doner (eds.). 1979. The history and philosophy of technology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Bunge, M. 1966/1974. Technology as applied science. Technology and Culture 7:329–347. Reprinted in F. Rapp (ed.), Contributions to a philosophy of technology, 19–36. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Bunge, M. 1985. Epistemology and methodology III: Philosophy of science and technology. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Bynum, T.W., and S. Rogerson. 2004. Computer ethics and professional responsibility. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Byrne, E.F. (ed.). 1989. Technological transformation. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Calluzzo, V.J., and Ch.J. Cante. 2004. Ethics in information technology and software use. Journal of Business Ethics 51(3): 301–312.

Camarinha-Matos, L.M., E. Shahamatnia, and G. Nunes (eds.). 2012. Technology innovation for value creation proceedings. New York: Springer.

Carolan, M. 2007. The precautionary principle and traditional risk assessment. Organization and Environment 20(1): 5–24.

Carpenter, S. 1983. Technoaxiology: Appropriate norms for technology assessment. In Philosophy and technology, ed. P. Durbin and F. Rapp, 115–136. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Christophorou, L.G., and K.G. Drakatos (eds.). 2007. Science, technology and human values: International symposium proceedings. Athens: Academy of Athens.

Clark, A. 2003. Natural-born cyborgs: Minds, technologies and the future of human intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Clarke, S. 2005. Future technologies, dystopic futures and the precautionary principle. Ethics and Information Technology 7(3): 121–126.

Collins, H.M. 1982. Frames of meaning: The sociological construction of extraordinary science. London: Routledge and K. Paul.

Constant, E. 1984. Communities and hierarchies: Structure in the practice of science and technology. In The nature of technological knowledge, ed. R. Laudan, 27–46. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Cranor, C.F. 2004. Toward understanding aspects of the precautionary principle. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy 29(3): 259–279.

Crombie, A.C. (ed.). 1963. Scientific change: Historical studies in the intellectual, social and technical conditions for scientific discovery and technical invention. From antiquity to the present. London: Heinemann.

Crousse, B., J. Alexander, and R. Landry (eds.). 1990. Evaluation des politiques scientifiques et technologiques. Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval.

D’Souza, C., and M. Taghian. 2010. Integrating precautionary principle approach in sustainable decision-making process: A proposal for a contextual framework. Journal of Macromarketing 30(2): 192–199.

Das, M., and S. Kolack. 1990. Technology, values and society: Social forces in technological change. New York: Lang.

Dasgupta, S. 1994. Creativity in invention and design. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dasgupta, S. 1996. Technology and creativity. New York: Oxford University Press.

De Solla Price, D.J. 1965. Is technology historically independent of science? A study in statistical historiography. Technology and Culture 6:553–568.

De Vries, M.J., S.E. Hansson, and A. Meijers (eds.). 2013. Norms in technology. Dordrecht: Springer.

Dosi, G. 1982. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories: A suggested interpretation of the determinants and directions of technological change. Research Policy 11: 147–162.

Durbin, P. (ed.). 1987. Technology and responsibility. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Durbin, P. (ed.). 1989. Philosophy of technology. Practical, historical and other dimensions. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Durbin, P. (ed.). 1990. Broad and narrow interpretations of philosophy of technology. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Durbin, P., and F. Rapp (eds.). 1983. Philosophy and technology. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Echeverria, J. 2003. La revolución tecnocientífica. Madrid: FCE.

Elliott, B. 1986. Technology, innovation and change. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

Ellul, J. 1954/1990. La technique; ou, L’en jeu du siècle. Paris: A. Colin, (2nd ed. revised, Paris: Economica, 1990.) Translated from the French by John Wilkinson with an introd. by Robert K. Merton: Ellul, J. 1964. The technological society. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Elster, J. 1983. Explaining technical change: A case study in the philosophy of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Feenberg, A. (ed.). 1995. Technology and the politics of knowledge. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Feibleman, J.K. 1982. Technology and reality. The Hague: M. Nijhoff.

Fellows, R. (ed.). 1995. Philosophy and technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Floridi, L. (ed.). 2004. Philosophy of computing and information. Oxford: Blackwell.

Floridi, L. (ed.). 2010. Information and computing ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, C., and L. Soete. 1997. Economics of industrial innovation, 3rd ed. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Fuller, S. 1993. Philosophy, rethoric, and the end of knowledge: The coming of science and technology studies. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

García-Muina, F.E., E. Pelechano-Barahona, and J.E. Navas-López. 2011. The effect of knowledge complexity on the strategic value of technological capabilities. International Journal of Technology Management 54(4): 390–409.

Gehlen, A. 1965/2003. Anthropologische Ansicht der Technik. In Technik im technischen Zeitlater, eds. H. Freyer, J.Ch. Papalekas and G. Weippert. Düsserdorf: J. Schilling. Translated in abridged version as Gehlen, A. 2003. A philosophical-anthropological perspective on technology. In Philosophy and technology: The technological condition, eds. R.C. Scharff and V. Dusek, 213–220. Oxford: Blackwell.

Glendinning, Ch. 2003. Notes toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto. In Philosophy and technology: The technological condition, ed. R.C. Scharff and V. Dusek, 603–605. Oxford: Blackwell.

Goldman, S.L. (ed.). 1989. Science, technology, and social progress. Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press (Coedited by Associated University Presses, London).

Gómez, A. 2001. Racionalidad, riesgo e incertidumbre en el desarrollo tecnológico. In Filosofía de la Tecnología, ed. J.A. López Cerezo, J.L. Luján, and E.M. García Palacios, 169–187. Madrid: Ed. OEI.

Gómez, A. 2002. Estimación de riesgo, incertidumbre y valores en Tecnología. In Tecnología, civilización y barbarie, ed. J.M. De Cozar, 63–85. Barcelona: Anthropos.

Gómez, A. 2003. El principio de precaución en la gestión internacional del riesgo. Política y Sociedad 40(3): 113–130.

Gómez, A. 2007. Racionalidad y responsabilidad en Tecnología. In Los laberintos de la responsabilidad, ed. R. Aramayo and M.J. Guerra, 271–290. Madrid: Plaza y Janés.

Gonzalez, W.J. 1990. Progreso científico, Autonomía de la Ciencia y Realismo. Arbor 135(532): 91–109.

Gonzalez, W.J. 1996. Towards a new framework for revolutions in science. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 27(4): 607–625.

Gonzalez, W.J. 1997. Progreso científico e innovación tecnológica: La ‘Tecnociencia’ y el problema de las relaciones entre Filosofía de la Ciencia y Filosofía de la Tecnología. Arbor 157(620): 261–283.

Gonzalez, W.J. 1998a. Racionalidad científica y racionalidad tecnológica: La mediación de la racionalidad económica. Ágora 17(2): 95–115.

Gonzalez, W.J. 1998b. Prediction and prescription in economics: A philosophical and methodological approach. Theoria 13(32): 321–345.

Gonzalez, W.J. 1999a. Valores económicos en la configuración de la Tecnología. Argumentos de Razón Técnica 2: 69–96.

Gonzalez, W.J. 1999b. Ciencia y valores éticos: De la posibilidad de la Ética de la Ciencia al problema de la valoración ética de la Ciencia Básica. Arbor 162(638): 139–171.

Gonzalez, W.J. (ed.). 2005a. Science, technology and society: A philosophical perspective. A Coruña: Netbiblo.

Gonzalez, W.J. 2005b. The philosophical approach to science, technology and society. In Science, technology and society: A philosophical perspective, ed. W.J. Gonzalez, 3–49. A Coruña: Netbiblo.

Gonzalez, W.J. 2008. Economic values in the configuration of science. In Epistemology and the social, Poznan studies in the philosophy of the sciences and the humanities, ed. E. Agazzi, J. Echeverría, and A. Gómez, 85–112. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Gonzalez, W.J. 2011a. Complexity in economics and prediction: The role of parsimonious factors. In Explanation, prediction, and confirmation, ed. D. Dieks, W.J. Gonzalez, S. Hartman, Th. Uebel, and M. Weber, 319–330. Dordrecht: Springer.

Gonzalez, W.J. 2011b. Conceptual changes and scientific diversity: The role of historicity. In Conceptual revolutions: From cognitive science to medicine, ed. W.J. Gonzalez, 39–62. A Coruña: Netbiblo.

Gonzalez, W.J. 2013a. Value ladenness and the value-free ideal in scientific research. In Handbook of the philosophical foundations of business ethics, ed. Ch. Lütge, 1503–1521. Dordrecht: Springer.

Gonzalez, W.J. 2013b. The sciences of design as sciences of complexity: The dynamic trait. In New challenges to philosophy of science, ed. H. Andersen, D. Dieks, W.J. Gonzalez, Th. Uebel, and G. Wheeler, 299–311. Dordrecht: Springer.

Gonzalez, W.J. 2013c. The roles of scientific creativity and technological innovation in the context of complexity of science. In Creativity, innovation, and complexity in science, ed. W.J. Gonzalez. 11–40. A Coruña: Netbiblo.

Graham, G. 1999. The internet: A philosophical inquiry. London: Routledge.

Habermas, J. 1968a/1971. Erkenntnis und Interesse. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. Translated by Jeremy J. Shapiro. Knowledge and human interests. Boston: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. 1968b. Technik und Wissenschaft als “Ideology”. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Hacking, I. 1983. Representing and intervening. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Hacking, I. 1999. The social construction of what? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hanks, C. (ed.). 2010. Technology and values: Essential readings. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Haraway, D. 1991. Simians, cyborgs and women: The reinvention of nature. New York: Routledge and Institute for Social Research and Education.

Heidegger, M. 1954/2003. Die Frage nach der Technik. In Vorträge und Aufsätze, ed. M. Heidegger, 13–44. Pfullingen: Günther Neske. Translated as Heidegger, M. The question concerning technology. In Philosophy and technology: The technological condition, eds. R. C. Scharff and V. Dusek, 252–264. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hiskes, A.L.D. 1986. Science, technology, and policy decisions. Boulder: Westview Press.

Hottois, G. 1990. Le paradigme bioéthique: une éthique pour la technoscience. Brussels: De Boeck-Wesmael.

Ihde, D. 1979. Technics and praxis: A philosophy of technology. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Ihde, D. 1983. Existential technics. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Ihde, D. 1991. Instrumental realism: The interface between philosophy of science and philosophy of technology. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Ihde, D. 2004. Has the philosophy of technology arrived? A state-of-the-art review. Philosophy of Science 71(1): 117–131.

Ihde, D., and E. Selinger (eds.). 2003. Chasing technoscience: Matrix for materiality. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Isaacson, W. 2011. Steve Jobs. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Jacquette, D. (ed.). 2009. Reason, method, and value. A reader on the philosophy of Nicholas Rescher. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Jasanoff, S., G.E. Markle, J.C. Petersen, and T. Pinch (eds.). 1995. Handbook of science and technology studies. London: Sage.

Jaspers, K. 1958. Die Atom-bombe und die Zukunft der Menschen. Munich: Piper.

Jonas, H. 1979/1984. Das Prinzip Verantwortung. Versuch einer Ethik für die technologische Zivilisation. Frankfurt am Main: Insel. Translated as Jonas, H. The imperative of responsibility: In search of an ethics for the technological age. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Kitcher, Ph. 2001. Science, truth, and democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kopelman, L.M., D.B. Resnik, and D.L. Weed. 2004. What is the role of the precautionary principle in the philosophy of medicine and bioethics? The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy. A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine 29(3): 255–258.

Ladriere, J. 1977/1978. Les enjeux de la rationalité: le defí de la science et de la technologie aux cultures. Paris: Aubier/Unesco. Translated as Ladriere, J. The challenge presented to culture by science and technology. Paris: UNESCO.

Latour, B. 1987. Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B., and S. Woolgar. 1979/1986. Laboratory life: The social construction of scientific facts. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2nd ed., 1986).

Laudan, R. (ed.). 1984. The nature of technological knowledge: Are models of scientific change relevant? Dordrecht: Reidel.

Lelas, S. 1993. Science as technology. The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 44: 423–442.

Lenk, H. 2007. Global technoscience and responsibility: Schemes applied to human values, technology, creativity and globalisation. London: LIT.

Lowrance, W.W. 1986. Modern science and human value. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lowrance, W.W. 2010. The relation of science and technology to human values. In Technology and values: Essential readings, ed. C. Hanks, 38–48. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. (From Lowrance (1986), pp. 145–150.)

Lujan, J.L. 2004. Principio de precaución: Conocimiento científico y dinámica social. In Principio de precaución, Biotecnología y Derecho, ed. C.M. Romeo Casabona, 221–234. Granada: Comares/Fundación BBVA.

Lujan, J.L., and J. Echeverria (eds.). 2004. Gobernar los riesgos. Ciencia y valores en la Sociedad del riesgo. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva/OEI.

Macpherson, C.B. 1983. Democratic theory: Ontology and technology. In Philosophy and technology, ed. C. Mitcham and R. Mackey, 161–170. New York: The Free Press.

Magnani, L., and N.J. Nersessian (eds.). 2002. Model based reasoning: Science, technology, values. New York: Kluwer Academic/ Plenum Publishers.

Maguire, S., and J. Ellis. 2010. The precautionary principle and risk communication. In Handbook of risk and crisis communication, ed. R.L. Heath and D. O’Hair, 119–137. New York: Routledge.

McKinney, W.J., and H. Hammer Hill. 2001. Of sustainability and precaution: The logical, epistemological and moral problems of the precautionary principle and their implications for sustainable development. Ethics and the Environment 5(1): 77–87.

Meyers, R.A. (ed.). 2012. Encyclopedia of sustainability science and technology. New York: Springer.

Michalos, A. 1983. Technology assessment, facts and values. In Philosophy and technology, ed. P. Durbin and F. Rapp, 59–81. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Mitcham, C. 1980. Philosophy of technology. In A guide to the culture of science, technology and medicine, ed. P. Durbin, 282–363. New York: The Free Press.

Mitcham, C. 1994. Thinking through technology. The path between engineering and philosophy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Mitcham, C., and R. Mackey. (eds.). 1983. Philosophy and technology: Readings in the philosophical problems of technology. New York: Free Press (1st ed., 1972).

Mitcham, C., and K. Waelbers. 2009. Technology and ethics: Overview. In A companion to the philosophy of technology, ed. J.-K. Berg Olsen, S.A. Pedersen, and V.F. Hendricks, 367–383. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mohapatra, K.M. (ed.). 2004. Technology, environment and human values: A metaphysical approach to sustainable development. New Delhi: Concept Publishing.

Myers, N. 2002. The precautionary principle puts values first. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society 22(3): 210–219.

Neely, K.A., and H.C. Luegenbiehl. 2008. Beyond inevitability: Emphasizing the role of intention and ethical responsibility in engineering design. In Philosophy and design: From engineering to architecture, ed. P. Vermaas et al., 247–257. Dordrecht: Springer.

Niiniluoto, I. 1990. Should technological imperatives be obeyed? International Studies in the Philosophy of Science 4: 181–187.

Niiniluoto, I. 1993. The aim and structure of applied research. Erkenntnis 38: 1–21.

Niiniluoto, I. 1994. Nature, man, and technology – Remarks on sustainable development. In The changing circumpolar north: Opportunities for academic development, vol. 6, ed. L. Heininen, 73–87. Rovaniemi: Arctic Centre Publications.

Niiniluoto, I. 1995. Approximation in applied science. Poznan Studies in the Philosophy of Science and Humanities 42: 127–139.

Niiniluoto, I. 1997a. Ciencia frente a Tecnología: ¿Diferencia o identidad? Arbor 157(620): 285–299.

Niiniluoto, I. 1997b. Límites de la Tecnología. Arbor 157(620): 391–410.

Ojha, S. 2011. Science, technology and human values. New Delhi: MD Publications.

Olive, L. 1999. Racionalidad científica y valores éticos en las Ciencias y la Tecnología. Arbor 162(637): 195–220.

Olsen, J.K.B., S.A. Pedersen, and V.F. Hendricks (eds.). 2009. A companion to the philosophy of technology. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ortega y Gasset, J. 1939/1997. Ensimismamiento y alteración. Meditación de la Técnica. Buenos Aires: Espasa-Calpe. Reprinted in Ortega y Gasset, J. Meditación de la Técnica. Madrid: Santillana.

Peterson, M. 2007. Should the precautionary principle guide our actions or our beliefs? Journal of Medical Ethics 33(1): 5–10.

Pinch, T.J., and W.E. Bijker. 1984. The social construction of facts and artefacts: Or how the sociology of science and the sociology of technology might benefit each other. Social Studies of Science 14:399–441. Published, in a shortened and updated version, as Pinch, T.J., and W.E. Bijker. 2003. The social construction of facts and artefacts. In Philosophy and technology: The technological condition, eds. R. C. Scharff and V. Dusek, 221–232. Oxford: Blackwell.

Pitt, J. (ed.). 1995. New directions in the philosophy of technology. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Pitt, J. 2000. Thinking about technology: Foundations of the philosophy of technology. New York: Seven Bridges Press.

Radnitzky, G. 1978. The boundaries of science and technology. In The search for absolute values in a changing world, Proceedings of the VIth international conference on the unity of sciences, vol. II, 1007–1036. New York: International Cultural Foundation Press.

Rapp, F. (ed.). 1974. Contributions to a philosophy of technology. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Rapp, F. 1978. Analitische Technikphilosophie. Munich: K. Alber.

Regan, P.M. 2009. Legislating privacy: Technology, social values and public policy. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Rescher, N. 1980. Unpopular essays on technological progress. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Rescher, N. 1983. Risk: A philosophical introduction to the theory of risk evaluation and management. Lanham: University Press of America.

Rescher, N. 1984/1999. The limits of science. Berkeley: University of California Press. Revised edition. The limits of science. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Rescher, N. 1999. Razón y valores en la Era científico-tecnológica. Barcelona: Paidós.

Rescher, N. 2003. Sensible decisions. Issues of rational decision in personal choice and public policy. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Rescher, N. 2009. The power of ideals. In Reason, method, and value. A reader on the philosophy of Nicholas Rescher, ed. D. Jacquette, 335–345. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Ricci, G.R. (ed.). 2011. Values and technology. New Brunswick: Transactions Publishers.