Abstract

The aim of the paper is to question the scope and limits of reconciliation as an effective peace-building process. It is to problematize a notion that is often taken for granted and to contribute to the understanding of the dynamics that take place between former enemies, and between various groups of actors on each side (be they survivors, policy-makers, perpetrators or outsiders such as international donors, practitioners, diplomats and scholars). To understand these dynamics, it seems fundamental to question the normative frame of reconciliation after wars and mass atrocities. Is reconciliation an unequivocal goal to be pursued whatever the circumstances? Beyond a theoretical interest, this question has a direct impact for practitioners; a better understanding of the issue is actually a sine qua non condition for more efficient interventions. The paper is divided into three parts. The first emphasizes the major conceptions of reconciliation as a peace-building process. The second stresses the attitude of the reconciliation advocates in Rwanda. Beside the official authorities, most peace builders called for reconciliation and forgiveness. The third and final part serves as a reminder that some survivors decided to resist this call for reconciliation.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

4.1 Introduction

Over the last 15 years, research was carried out on memory and conflict resolution in a variety of contexts in Europe, the Balkans, and the Great Lakes Region of Africa. This research has emphasized the existence of two contrasting and even contradictory attitudes regarding reconciliation. On the one hand, official representatives steadily call for reconciliation before, during, or after conflicts. Similarly, NGO workers in the field of conflict resolution often consider reconciliation as the ultimate achievement while more and more scholars determine reconciliation to be “probably the most important condition” for maintaining a stable peace (Bar-Siman-Tov 2000, p. 237). Thus, official representatives, practitioners and scholars often present reconciliation as both possible and essential to promote post-conflict stability. On the other hand, in the immediate aftermath of a violent conflict, victims or their relatives largely distrust the notion of reconciliation. Many of them feel animosity and bitterness towards what they perceive as an “indecent” injunction (Brudholm and Rosoux 2013) to reconcile with their enemies. Rather than seeing it as a strategy to move forward, reconciliation is perceived as a mere rhetoric that diminishes the sufferings endured in the past.

The gap between these two attitudes is the origin of the key question this paper seeks to address: how can we understand that the same notion of reconciliation is often presented as a panacea by policymakers, practitioners and scholars while it is much of the time stigmatized and rejected on the ground? The main hypothesis underlying the analysis is that both attitudes need to be taken seriously into account to determine the scope and, above all, the limits of reconciliation as an effective peace-building process.

The aim of the paper is neither to adopt a cynical position that would categorically belittle efforts in favour of a rapprochement between former adversaries, nor to consider reconciliation as the medicine to be systematically prescribed for ‘healing’ individual and social wounds after a conflict. The purpose is to question reconciliation as an agreed upon norm of conflict resolution. It is to problematize a notion that is too often taken for granted and to contribute to the understanding of the dynamics that take place between former enemies, and between various groups of actors on each side (be they survivors, policy-makers, perpetrators or outsiders such as international donors, practitioners, diplomats and scholars). To understand these dynamics, it seems fundamental to question the normative frame of reconciliation after wars and mass atrocities. Is reconciliation per se indeed a natural, legitimate and highly desirable purpose? Is it an ethical demand and unequivocal goal to be pursued whatever the circumstances?

Beyond a theoretical interest, this question has a direct impact for practitioners; a better understanding of the issue is actually a sine qua non condition for more efficient interventions. From that perspective, the issue is a crucial policy question everywhere and at all levels. Calling for reconciliation whatever the circumstances, particularly when the concept is poorly defined, can be futile or even counterproductive.

In terms of methodology, the analysis is largely devoted to the Rwandan case since this case illustrates a general problem that is raised in other parts of the world of how to promote coexistence after crimes “that one can neither punish, nor forgive” (Arendt 1961, p. 307). Two main kinds of data are combined to dissect the attempts of rapprochement between the Rwandan national components. First, a systematic corpus of official speeches allows for a description of the evolution of the Rwandan authorities since the end of the hostilities. Second, a comprehensive gathering of narratives depicts the reactions of specific individuals directly affected by a violent past.

The paper is divided into three parts. The first emphasizes the major conceptions of reconciliation as a peace-building process. The second stresses the attitude of the reconciliation advocates in Rwanda. Beside the official authorities, most peace builders called for reconciliation and forgiveness. The third and final part serves as a reminder that some survivors decided to resist this call for reconciliation. By attending to their voices, this article attempts to challenge reconciliation rhetoric, given—and often stereotypical—conceptions of unforgiving victims. In doing so, it does not pretend to represent ‘the victims’ as a general category, but rather to illustrate the possibility of an often-neglected normative stance.

4.2 Three Major Pieces of the Puzzle

A certain conceptual vagueness forces us to raise a basic question to avoid any confusion: what are we talking about when we talk about reconciliation? Beyond the flourishing and sometimes competing theoretical classifications, three main approaches to political reconciliation can be distinguished: structural, psycho-social and spiritual. However, this concept is so rich that any classification system could be easily challenged.Footnote 1 Since the aim of this chapter is not to settle the issue from a theoretical point of view we will not get involved in an academic debate about labels and categorizations.

The first approach prioritizes security, economic interdependence and political cooperation between parties (Kacowicz et al. 2000). The second underlines the cognitive and emotional aspects of the process of rapprochement between former adversaries (Bar-Siman-Tov 2004). The third accentuates a process of collective healing based on the rehabilitation of both victims and offenders (Tutu 1999). In short, the structural approach generally deals with the interests and the issues at stake, whereas the two others concentrate on the relationships between the parties.

4.2.1 Structures and Institutions

After the cessation of violent acts, parties in conflict can establish mutually accepted structural and institutional mechanisms to reduce the general perception of threat and to resolve any possible and critical disagreement. When the former belligerents live in different states, these mechanisms can take the form of confidence-building measures like exchanging representatives in various political, economic, and cultural spheres; maintaining formal and regular channels of communication and consultation between public officials; developing joint institutions and organizations to stimulate economic and political interdependence; and reducing tensions by disarmament, demobilization of military forces and the demilitarization of territories. The Franco-German case illustrates the effectiveness of such structural measures. Six years after the end of World War II, an economic union for coal and steel production was created; in 1963, Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer signed the Élysée Treaty which institutionalized regular meetings between foreign, defence and education ministers; in 1988, the Franco-German Council was established and in 1995, joint military units were formed (Ackermann 1994). When adversaries live together in one single state, structural measures mainly concern institutional reforms. Their purpose is to integrate all the groups in a democratic system, restore human and civil rights and favour a fair redistribution of wealth. The negotiations that made the South African transition possible exemplify the complexity of this process.

4.2.2 Relationships

Although some structural changes can be implemented relatively quickly after the end of a conflict, the transformation of relationships does not occur in the same way. Many studies are dedicated to this slow and arduous process between former belligerents or between victims and perpetrators. They are often interconnected but their vision of the transformation process is diverging. Cognitive and psycho-social approaches analyse what they call a “deep change” in the public’s psychological repertoire. This evolution results from a reciprocal process of adjustments of beliefs, attitudes, motivations and emotions shared by the majority of society members (Bar-Tal and Bennink 2004, p. 17; Stover and Weinstein 2004, p. 202). From that perspective, the goal pursued by the reconciliation process is to forge a new relationship between the parties.

By contrast, the so-called spiritual approaches attempt to understand how parties can restore a broken harmonious relationship between the parties. They go a step further by asserting that reconciliation attempts should lead to forgiveness for the adversary’s misdeeds (Shriver 1995; Lederach 1998; Staub 2000; Philpott 2006). The reference to the “spirit of reconciliation”Footnote 2 is not only made by theologians and scholars, but also by policy-makers. German Foreign Minister, Guido Westerwelle, for instance frequently mentioned this “spirit” as being at the origin of the mutual trust, which made European integration possible (Pristina, August 27, 2010; Zagreb, August 25, 2010; Berlin, October 29, 2010). Former Australian Prime minister, Kevin Rudd, went even further in emphasizing the “sacrament of reconciliation” (Sydney, February 11, 2011). Figure 4.1 presents the three main approaches to political reconciliation, the focus of each approach and their ultimate aim.

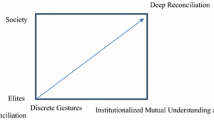

Facing this plurality of interpretations of reconciliation, two main strategies can be adopted. The first consists in combining them in order to encompass the whole picture of reconciliation efforts. This attitude makes sense particularly if one realizes that each of these conceptions focuses on a specific piece of the puzzle to be understood. Accordingly, the approaches can be conceived as successive stages of a long-term process. It can indeed be argued that in some specific cases, the rapprochement that took place between former adversaries started by a pragmatic deal between parties, leading to common projects and institutions; that these confidence-building measures created conditions for a progressive transformation of relationships; and, lastly, that this process impacted every single individual affected by the violence in one way or another (Fig. 4.2).

Framing reconciliation in terms of a timeline is illuminating. However, it rapidly reaches its limits when it is used in a prescriptive way. On the ground, practitioners involved in conflict transformation face major difficulties if they present reconciliation as a “kit for stabilizing peace” (Rosoux 2014). Indeed, how can strict sequencing be pertinent when the phenomenon actually requires a simultaneous change at different levels?

The second way to consider the approaches to reconciliation is to contrast them and to question their respective premises. Does a rapprochement between former adversaries depend more on institutional, psycho-social or spiritual changes? Is each of the approaches totally relevant to the field of international and/or inter-community relations? The advocates of a realist stance denounce the risk of sentimentalizing and depoliticizing the processes, while others claim that a substantial change cannot be imagined in emphasizing only institutional and legal instruments. This debate can be illustrated by the following spectrum between a minimalist conception, according to which reconciliation can actually be synonymous with conflict management, and a maximalist conception, which would support the idea of reconciliation as a transcendent process (Fig. 4.3).

If we keep this spectrum in mind, at least three distinct goals can be emphasized: coexistence, respect and harmony. Some peace builders conceive their objective in terms of coexistence between parties. Their aim is that former enemies live together non-violently, even though they still hate each other. The progress lies in the ability of the parties to comply with the law instead of killing each other. From that viewpoint, they tolerate each other because they have to: they stop fighting each other because it is in their own interests. This modus vivendi is certainly more satisfactory than violent conflict. However, the situation remains explosive. In order to prevent any potential recurrence of the violence, other voices consider that parties should attempt to do more than simply coexist in respecting each other as fellow citizens. In this view, former enemies may continue to strongly disagree and even to be adversaries, but they should be able to enter into a give and take about matters of public policy and progressively build on areas of common concern. This intermediary conception is based on the perception that some mutual interests exist and allow the parties to forge compromises. Last, more robust conceptions of reconciliation conceive a goal in terms of mercy (rather than justice), harmony and shared comprehensive vision (Crocker 1999). The Rwandan case presented in the next section manifests the rapid limits, and the potential detrimental character, of the maximalist approach in the aftermath of grave human rights violations.

4.3 Rwanda: Forgiveness as a Panacea

In Rwanda, between April and July 1994, all Tutsis, from babies to old men, were tracked. The machete also systematically fell on those among the Hutu designated as traitors. Within weeks, unprecedented violence was unleashed. Some Rwandans were forced to kill their spouse or their children. Unthinkable crimes. Unspeakable pain. The genocide was stopped at the time of the military victory of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) on July 18, 1994. In the aftermath of genocide, three million people were forced into exile. They fled into neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo where violence continues to this day. The RPF forcibly dismantled the camps of Hutu exiles who they felt continued to pose a threat to Rwandan security. Reports from the Commission on Human Rights of the United Nations (UN) and international NGOs such as Human Rights Watch (HRW), the International Federation of Human Rights (IFDH) and Amnesty International (AI) reported on abuses allegedly committed in these camps by the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), military wing of the RPF in 1994. The next year was particularly marked by the massacre of thousands of civilians in the camp of Kibeho.

Prior to 1994, violent episodes regularly broke the peaceful coexistence of the population. Far from being reduced to “collective murderous craze” (Sémelin 2005, p. 248), genocide is part of a historical context that, for decades, ate away at the thick social ties. In 1990, a civil war between government forces and the RPF broke out, itself the remnant of killings and subsequent exile of Tutsis that has repeated itself since independence (1959, 1963, 1965, 1966, and 1973). According to most observers, the seeds of strife were deposited during the colonial period that prioritized and froze in time the socio-economic characteristics of the population into ethnic groups, arbitrarily distinguished. The discourse made by the colonizers, whether pro-Tutsi or pro-Hutu (particularly the case after the so-called social revolution of 1959), gave a systematically biased and stereotypical view of intercommunity relations.

This brief overview makes it possible to take measure of the depth of the memories at the heart of the population. It is within this context that calls for national reconciliation are continuing to multiply in Rwanda. Regardless of whom the appeals are from—whether official authorities, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), churches or outside observers—all declare the same goal: to (re)build links between two communities torn apart. To do so, many protagonists do not hesitate to explicitly call for forgiveness. In doing so, they show how ambitious their expectations are.

4.3.1 An Official Shift

In Rwanda, after the genocide, the South African case was immediately pointed to as one of the potential models to imitate. Desmond Tutu visited the country a year after the genocide and warned that retributive justice would lead to a vicious circle of reprisals and counter-reprisals. He instead urged Rwandans to move restorative justice forward (Graybill 2002). However, the Rwandan president, Paul Kagame, responded that the severity of the crimes—the genocide of 800,000 Tutsis and political opponents (one-tenth of the population of Rwanda) implied imperative prosecutions. The option of a TRC was therefore rapidly dismissed. According to Charles Murigande, the former Rwandan minister of transport and telecommunication, Rwandans did not really need truth—“We know who did what. Unlike in South Africa where there were secret death squads – people here know what has happened. So simply telling Rwandans the truth and then giving people amnesty – that would not be very helpful” (quoted by Goodman 1997). Thus, Rwandan authorities chose a different way to deal with their past. Besides the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) established in 1994 to pursue the planners of the genocide, they passed legislation in 1996 authorizing prosecutions in state courts of those who had followed the orders. As Mahmood Mamdani explains: “If South Africa exemplifies the dilemma involved in the pursuit of reconciliation without justice, Rwanda exemplifies the opposite: the pursuit of justice without reconciliation” (1997). The one sentence we heard everywhere at that time was that Rwanda had to erase the culture of impunity that lasted for too long and that was partly at the origin of the genocide.

Yet, in 1999, a National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) was set up with a mandate that can be summarized as ‘promoting unity and reconciliation’, most visible through the organization of the Ingando solidarity camps for reintegration and re-education. Six years later, the gacaca courts were installed to prosecute and try the perpetrators of the crime of genocide and other crimes against humanity committed between 1 October 1990 and 31 December 1994. Originally designed for minor offences, the gacaca courts were adapted—with limited success—to handle many thousands of genocidaires. The new gacaca courts were based on participatory justice that uses the wisdom of respected leaders in the community to settle disputes. The principle was to gather the protagonists of the crime (survivors, witnesses, suspects) at the scene of the crimes and discuss what happened, discover the truth, make a list of victims, and designate the guilty.

In this line, a discourse of reconciliation has begun to surface. The shift is such that now every socio-political initiative is framed in terms of reconciliation. Two major reasons can be considered to understand this complete change. First, justice was de facto impossible—the number of people who had to be tried and sentenced was unmanageable (the judiciary system being totally ruined after the genocide). Second, justice was somehow embarrassing since it meant dealing with crimes committed on each side. Without making any slippery comparison between the genocide and what happened in the Congo after 1994, it is hard to deny the responsibility of the Rwandan Patriotic Army regarding the massacres of civilians that succeeded one another. When justice is seen as unrealistic and compromising, reconciliation appears as a legitimate and consensual objective.

As a result, Paul Kagame repeatedly presented reconciliation as a fundamental basis to rebuild the country (5 December 2006). His point went much further than arguing in favour of a structural rapprochement between the components of his nation. His approach to reconciliation is undeniably maximalist. At least two main elements demonstrate it. First, the goal stressed by Paul Kagame is not simply the coexistence of all Rwandan citizens, but rather a form of harmony within the whole society. Second, the Rwandan president put a constant emphasis on the notion of forgiveness. In 2002, he did not hesitate to encourage forgiveness on a national level: “The committed sins have to be repressed and punished, but also forgiven. I invite the perpetrators to show courage and to confess, to repent, and to ask forgiveness” (18 June 2002), and later: “It is important that culprits confess their crimes and ask forgiveness to victims. On the one hand, the confession appeases their conscience, but above all these avowals comfort the survivors who can then learn, even though it is painful, how their close relatives were killed and where their bodies where abandoned” (quoted by Braeckman 2004, p. 417). In April 2006, at the 12th commemoration of the Rwandan genocide, Paul Kagame emphasized again the notion of forgiveness in underlining the need to “confront the truth, to tolerate and to forgive for the sake of our future, to give the Rwandans their dignity” (7 April 2006).

Moreover, the notion of forgiveness is not only highlighted in the official speeches made in Rwanda. It is also a core issue of many statements abroad. Thus, in 2010, Paul Kagame addressed the Rwandan diaspora in Brussels in defining the “new Rwanda” as a place for “debate”, “compromise” and “forgiveness” (4 December 2010). The idea is quite similar when the representatives of an association called Unity Is Strength Foundation explained the necessity to “let the world see that the country is different from what is sometimes written in the media” (Belfior 2011). Speaking to the Press after meeting President Paul Kagame, the Dutch director of this association said: “We have been to the north, south, east and west of Rwanda and we have to share that special thing that this country has and bring it across. The process of reconciliation in this country is incredible. There is still a lot to be done, but the country is preparing itself for its future based on unity and forgiveness, a thing that even us Europeans have failed to do. It’s difficult to tell someone who killed your father and mother that you forgive him but this has happened here”.Footnote 3 These words summarize what we could call a moral lesson to the entire world—and particularly to those who dare criticize the Rwandan regime.

4.3.2 The Peace Builders’ Hope

This official emphasis on reconciliation and forgiveness highly resonates with the hope expressed by many practitioners. On the ground, several non-governmental organizations (NGOs) organize seminars that specifically tend to lead to forgiveness. Four documentaries are particularly emblematic in this regard: Icyizere Hope, As we forgive, Ingando – when enemies return, and Raindrop over Rwanda.Footnote 4 These reportages differ from each other, but they all concern the transformation of relationships between survivors and liberated prisoners. All of them confirm in a striking way the interviews made in Washington and in Brussels. Rather than explaining in detail each of these documentaries, it is worth underlining the major common features that characterize them. Five of them constitute what is conceived here as the reconciliation invariant elements.

-

a)

The films’ directors and the vast majority of the interviewed practitioners share a maximalist conception of reconciliation. In this regard at least, they seem to be in line with the official discourse, considering that “there is no limit to reconciliation” (United States Institute of Peace, Washington, 21 March 2011). The As We Forgive Initiative is presented as an effort “to transform communities by inspiring a grassroots movement of repentance, forgiveness, and reconciliation nationwide”. The spiritual dimension of the initiative is explicitly mentioned. The foundation of their work is “rooted in the Biblical values of forgiveness, repentance, and reconciliation based on the teachings of Jesus Christ”. According to them, “authentic transformation” in post-conflict societies can only occur “through the radical decision to repent and forgive”.Footnote 5 Beside this initiative, numerous religious leaders recommend unconditional forgiveness.

During my interviews, a unique scenario appeared as being both the structuring element and the aim of all narratives: a repentant perpetrator apologizes to a forgiving victim. The question is not if but when. The World Vision workshops are particularly telling as regards this scenario. Believing that reconciliation is a “prerequisite to the development process”, World Vision supports community initiatives that promote “community harmony”. During reconciliation workshops, genocide survivors, released prisoners, students or teachers are given forums to share their stories and, as they explain, learn about “the power of forgiveness”. Among all the stories emphasized by World Vision the story of Alice perfectly corresponds to the invariant scenario of reconciliation.

In 1994, Alice was holding her 9-month-old baby girl, when a mob of soldiers and interahamwe militias came and surrounded the swamp where she was hidden. They were armed with guns and machetes. One of them took her baby out of her hands and killed her. Then, a man named Emmanuel cut off Alice’s hand and slashed her face. She lost consciousness and was eventually rescued by Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) soldiers. Almost 20 years after the genocide, Alice’s memories are still fresh. She has a scar on her jaw and is missing a hand. However, with the help of World Vision workshops, as it is explained, she found the strength to forgive Emmanuel and the men who killed her baby: “In fact, Alice lost 100 members of her extended family, and yet she forgave”. The process is presented as almost miraculous: Emmanuel confessed, took full responsibility for his crimes and attended one of World Vision’s workshops where he met Alice for the first time since the attack. Alice forgave him and they both preach reconciliation in their community. At workshops, Emmanuel and Alice teach that “forgiveness and repentance benefit both the offender and the victim”. The attitude of Alice is presented as absolutely fruitful since World Vision discloses that “after forgiving Emmanuel, Alice and her husband were able to conceive again, and they now have five children”. To sum up the whole story, it is said that Alice “survived the unthinkable, forgave her attackers, and now works to bring peace and reconciliation to her country”.

-

b)

The encouraged rapprochement is based on a therapeutic conception of reconciliation. The notion of trauma is essential since all the protagonists are described as “traumatized”: survivors of course, perpetrators—depicted as fearful and ashamed, and descendants of both victims and perpetrators. In these conditions, it does not come as a surprise that the whole society requires a form of “authentic healing”. Therefore third parties are perceived as playing a critical role in curing and rescuing the whole society. The documentary As we forgive illustrates particularly well this dynamic. As the film’s director explains: “More and more Rwandans are discovering hope through reconciliation as perpetrators repent of their crimes and survivors find the strength to forgive. Our goal is to play a healing part in that process”.Footnote 6

One of the consequences of this view is the risk of putting victims and perpetrators on the same level, somehow gathered under a common ‘trauma’ label. As mentioned by the voice-over of the documentary Icyizere, Hope: “They are all more similar than different. They are all, victims and aggressors, suffering from trauma. The most effective way to overcome their trauma is by making an effort to forgive each other”. The argument is similar in the documentary Ingando where a former combatant confirms: “We have to forgive each other, to forget the bad story and be focused on the future”. Thus, the whole picture seems to be reduced to a collective healing process, no matter of the responsibility to take on.

-

c)

A third major element concerns the outcome of the narrative. Third parties systematically emphasize stories that lead to a happy end. The chosen protagonists overcome a tragic reality. After an initiatory journey, those who were almost broken stand up and move forward. The pattern is similar at the collective level. The finality, which is pursued, is to transform a devastated society into an energetic one. The dynamic allows the passage “from hopelessness to optimism” (Steward 2009, p. 187). The metaphor of the fairy-tale is enlightening in this regard. Interestingly far from the tragic dimension of all post-conflict realities, the depicted horizon is wide and bright. All characters are presented as evolving “beyond violence, beyond fear, beyond anger, beyond vengeance”.Footnote 7

In the films, this transformation is often incarnated by an enthusiastic Rwandan pupil, born after 1994. In the documentary Ingando, for instance, the selected Rwandan youth express their happiness to live what they call a “new national momentum” in the history of their country. The tone is identical in the film As we forgive, which gives the floor to an optimistic orphan of the genocide: “We are brothers and sisters, there is no ethnic division here. I want to build my country”. Her testimony stresses the importance of forgiveness in presenting it as both a trigger mechanism (“Before I forgave, I felt anger and I felt lonely”) and an inspiring lesson (“People from other countries also need reconciliation. Rwandans forgive each other”). According to the film director, who became the director of the NGO As we forgive, the happy end, which is detectable in the reportage, is currently confirmed on the ground. She indeed announces that more than 90 % of the participants in their workshop qualify the impact of the program as “positive and tangible” in their life (Washington, 25 May 2011). Little explanation was given regarding the surveys that led to this impressive figure. However, the most critical point is probably to convince the audience of the “power of radical reconciliation”.

-

d)

Accordingly, most projects emphasize the resilience of the Rwandan individuals—be they survivors, ex-genocidaires or returnees. The emphasis is deliberately put on edifying examples that the population can identify with. This dynamic is at the core of the numerous screenings of the film As we forgive. During each presentation, hundreds of genocide orphans and children of genocide survivors and perpetrators meet to watch the movie. Zainabo explains: “As a genocide orphan, I never thought murder could be forgiven. In the film, Chantale [survivor who struggled hard with herself in order to forgive the killer of his father] touched my heart and taught me forgiveness. I have decided that I, too, will forgive the person who has killed my father” (Washington, 25 May 2011). Like Chantale in the film, Immaculée Ilibagiza seemed like a hero. After surviving the genocide, Immaculée left the country and went to United States. In her book Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust, she depicts her journey to forgiveness (Ilibagiza 2007). The promotion of her book, which became a best-seller, is telling: “Her story of faith and forgiveness will change your life”. These words indicate that her message is not only intended for Rwandan survivors, but also for any potential reader.

Beyond the notion of forgiveness—which is far from being an automatic reaction as we will see, the concept of resilience is systematically highlighted by Western practitioners. Several survivors underline it as well. Berthe Kayitesi, for instance, refers to Boris Cyrulnik—who popularized the notion of resilience in France—in order to describe her fight as both a child and a head of family in the aftermath of the genocide (Kayitesi 2009, p. 62). In narrating the tragic fate of those who are overlooked and almost forgotten (“les oubliés des oubliés”), Berthe refuses to be locked up by the label of victim. To overcome the weight of a past that is more present than the present itself, she counts on education and wants to move forward. The profile of the Rwandan singer Corneille is similar in this regard. He was 16 years old when he witnessed the massacre of his family. As a refugee in Germany and then in Canada, he started writing songs that repeat that one can survive, go beyond the worst situation and still be happy.

Let us add that the accentuation of a much needed resilience confirms the official discourse on both sides of the Atlantic. In Rwanda, almost every single speech pronounced by Paul Kagame underlines the resilience of the Rwandan population.Footnote 8 The recurrence of the term is similarly striking in Barack Obama’s speeches.Footnote 9

-

e)

A last feature is essential to understand the approach adopted by third parties involved in post-conflict situations: the direct link between the program of reconciliation which is advocated on the ground and the personal life of practitioners who we met. Most of them spontaneously evoked the “crucial” dimension of reconciliation in their own life.Footnote 10 Likewise, Laura Waters, director of the documentary film As we forgive, explained that forgiveness was “decisive” in her private life (see Oppenheim 2008). The passage from the individual level (her own experience) to the collective level (the post-genocide context) is audacious. One can indeed wonder to what extent the fact that Laura Waters saved her couple thanks to her ability to forgive her fiancé can enlighten the way to deal with genocide.

The link between private life and national reconciliation is also apparent in the messages intended for the international audience—and not only the local one in Rwanda. The trailers of the selected documentary films are emblematic in this regard. If we take the example of As we forgive, the link is explicitly made. The final sequence is made of a succession of stunning images on the pattern of a thriller. Reaching its highest point, the suspense led to the crucial question: “Could you forgive?”

4.4 Transgression of the Norm

In Rwanda, the attitude of many survivors arouses admiration and even sometimes fascination. Those who stand up and move forward are qualified as “exemplary”. On the international scene, this posture is unanimously celebrated. CNN reportages, International Awards and Doctorates Honoris Causa all over the world reward those who demonstrate that one can survive in a constructive and dignified way despite the most horrendous adversity.Footnote 11 However, it is worth thinking about the ultimate consequences of this phenomenon. What does happen when the unanimously honoured scenario is not only an inspiring example but becomes a model to which all protagonists have to correspond? What if this model is perceived as the panacea to be applied in any circumstance? In other words, how can people resist this norm? There is much at stake. In stigmatizing—even implicitly—the victims who don’t fit the reconciliation heroes’ ideal, peace builders mean that some victims are desirable and some not. The good ones are forgiving and resilient ones, while the bad ones wrestle with their resentments.

This perspective forces us to take a closer look at some of the voices of resistance, Esther Mujawayo’s in particular.Footnote 12 Born in Rwanda in 1958, she is a sociologist and a psychotherapist. In 1994, she lost hundreds of relatives—including her mother, father and husband—during the genocide. She now lives in Düsseldorf, Germany, and works in the field of trauma therapy with refugees. She wrote about her experience in two books entitled Survivantes (2004) and La fleur de Stéphanie (2006). What one finds in these writings is not the often-praised voice of the forgiving and conciliatory victim. To the contrary, even though Mujawayo endorses a gradual rapprochement between Rwandans in the long run, she clearly expresses her refusal to forgive, and talks of the inclination to forgive as a temptation. More than that, she talks about the interest in post-atrocity forgiveness as an “obsession”—not on behalf of the survivors, but on behalf of the authorities, NGOs, and other agents of reconciliation (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2006, pp. 17 and 127). What accounts for such “negative” attitudes to the advocacy of forgiveness? Of course, a comprehensive exploration is impossible here, but focusing on three different and partly successive reactions depicted by most of the Rwandan survivors will to some extent illuminate what lies behind this kind of resistance. The first is summarized by a single word: silence. The second is a strong refusal to forgive. The third, more global, one is a distancing from any ‘politics of reconciliation’. Each of these reactions indicates the limits of a reconciliation that would be presented as a miraculous formula.

4.4.1 Silence

Although questions of forgiveness loom large in current discourse on reconciliation, the issues faced most urgently by genocide survivors do not always or necessarily involve either forgiveness, anger, or its overcoming. Instead, the response to past atrocity can engage deep sadness, fear, loss of trust and hope, and other emotions that might lead to silence rather than to calls for justice and accountability. In her first book, Esther Mujawayo depicts the initial reaction of most of the survivors after the genocide: “No one… explicitly asked us to be quiet, [but] we have immediately felt that we had to [be]” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2004, p. 20).

The sheer difficulty of finding proper words, as well as listeners, is not the only reason for this first reaction. Many survivors decided to be silent because they felt guilty, ashamed, or afraid. The paradoxical guilt experienced by many of the other survivors around Esther Mujawayo resulted from the fact that they—and not the others—survived, that they could not save their loved ones, or that they could not find their loved ones’ bones. As for the shame, this feeling is often linked with the violence, especially sexual violence that they suffered. Even though 80 % of the women who survived were raped, the reality of this specific violence is still a taboo (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2004, p. 196). According to the representatives of the Association Avega (Association of the Widows of the Genocide), “[T]he rape, you bear it silently, in such a shame that no one could even imagine. But you, you always feel like a stink inside your body and a grime that itches your skin” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2004, p. 201). This shame and constant humiliation—reinforced by the stigmatization of any one Tutsi, systematically identified with a cockroach during the genocide—are so deep that the roles seem reversed: “The survivor is ashamed to meet the killer of his close relatives; he [the survivor] is the one who is afraid, who feels humiliated to see the perpetrator walking like that. He feels so guilty” (Mukayiranga 2004, p. 783).

This sense of the survivor’s guilt and shame can be associated with another cruel inversion of the roles during the genocide—when the victims themselves asked for forgiveness from their perpetrators. Several witnesses explained that, in front of the Interahamwe, victims were indeed asking for forgiveness in order not to be tortured for too long (Hatzfeld 2007, pp. 135–137). The fear expressed by the survivors can be explained by various elements: angst about not being believed, anxiety in front of recently liberated perpetrators, and a general feeling that they would be bothering everybody. With the ‘un-listenable’ mingling with the unspeakable, both tendencies imply a loss of confidence in the world and the loss of any sense of personal safety. Facing these extreme difficulties, the Rwandan victims have to make an immense effort to testify in front of a sometimes-hostile gathering, to express publicly tragic facts (above all sexual violence), to denounce neighbours, or even members of their own family. As Mujawayo noticed, in these circumstances forgiveness is not the primary concern of the survivor (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2006, p. 127).

Arguably, this kind of ‘distancing’ from the entire issue of forgiveness is not an example of resistance to forgiveness in the sense of active and focused opposition. But the situation is prone to feed into a kind of loathing and disdain that is as significant as the more-explicit forms of opposition. Consider for example this remark by Innocent Rwililiza, as quoted in one of Jean Hatzfeld’s books on post-genocide Rwanda: “Actually, who is speaking about forgiveness? Tutsis, Hutus, liberated prisoners, their families? None of them, it is the humanitarian organizations. They import forgiveness in Rwanda, and they wrap it in dollars to convince us. There is a Forgiveness Plan as there is an Aids Plan, with meetings of popularization, posters, little local presidents, very polite Whites in cross-country and turbo vehicles….We, we speak about forgiveness to be well considered and because subsidies can be lucrative. But in our intimate talks, the word ‘forgiveness’ is strange, I mean constraining (Hatzfeld 2007, p. 25).

4.4.2 Clear Refusal to Forgive

Beyond this first reaction, Mujawayo insists on her resistance to any kind of forgiveness toward perpetrators. She says, “the more I think about that, the more I ignore what forgiving means, except this mini-settlement that I make with myself to hold out[] for a pretended moral appeasement, to ‘win’ against hatred… . Today, as the years go, I accept better, I finally accept that, no, I will not forgive” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2006, p. 126). This position relies on two main reasons: on the one hand, the lack of energy to adopt an empathetic view of perpetrators, and, on the other, a deep discontent with what might be called a “cheap” repentance. Speaking about the killers, Mujawayo explains that empathy must follow a return of her energy: “I don’t want to understand them, at least, not yet. I want to proceed step by step: within ten years maybe. I don’t want to understand… . I say to myself that some people are paid for that, for understanding the killers—politicians, humanitarian staff, right-thinking people…. all those whose work is to get into contact with criminals. Myself, I don’t need that. I don’t want to understand them and I don’t want to excuse them. They did it… . and I want them to pay for that and not to sleep soundly” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2004, p. 87).

This refusal to understand the ‘other’ to some extent results from the immense fatigue felt by survivors who have so many other priorities in the current Rwandan context. Before thinking about the potential scope of empathy, Mujawayo wants “some bread for those who survived” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2006, p. 189). However, apart from the inappropriate character of any “duty to understand”, she does not deny the humanity of each Rwandan, including perpetrators: “Yes, there is a human touch in each of us, and therefore in each of them, and who knows what we could have done in their place” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2004, p. 120).

Mujawayo’s attitude seems to be characterized by a constant effort to take into consideration the ambivalence and complexity of the situation. Underlining the loneliness that goes with the experience of victims, she does not expect any kind of revenge in order to appease this feeling. Nonetheless, she maintains that victims have the right not to be above resentment. Being a psychotherapist, she does not feel any guilt when she faces her own resentment. Taking lucid account of the limits of her powers, she knows and she accepts that, for most survivors, full empathy would be unattainable and even counterproductive.

The second reason for survivors’ resistance to forgiveness is that forgiveness does not make sense when perpetrators do not express any remorse. According to Mujawayo, “most of the killers do not ask forgiveness, they say sorry. Or they ask it with the certainty that this request inherently merits a positive answer” (2006, p. 125). To her, the notion of forgiveness is not the same for the killer and the survivor. For the perpetrator, it represents a potential reduction of sentence, whereas for the victim it appears either as something beyond reach or as a sacrifice. Against this background, Mujawayo wonders, “To forgive whom in fact? The one who writes you his letter of repentance?” This question denounces the quasi-administrative letters written by perpetrators in order to be liberated as soon as possible. To Mujawayo, these documents at best mimic a true acknowledgment of responsibility and a genuine address to the survivors. In La Fleur de Stéphanie, she gives an example of the hundreds of similar letters sent to survivors:

Musange, province of Gitarama

Object: [T]o ask forgiveness [of] Nyirakanyana Madalina’s family

“I, N.V., son of K., I am writing to Nyirakanyana Madalina’s family, asking them forgiveness because I was one member of the group that took her from M.P.’s house (a neighbour)…. This group was directed by M.F…. [a list of 11 members follows]. These are those with whom we took her together to the river Nyabarongo but I, at that moment, I stopped on the riverside. Then, I ask you, the members of Nyirakanyana’s family, forgiveness; to the State, I also ask to forgive me, to God too I ask forgiveness, and I hope that you will forgive me as well. Peace of God with you”.

[Following is a signature, a name, and fingerprints.] A last sentence specifies: “This letter is notified to the gacaca coordinator of M Muhanga.” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2004, pp. 128–129).

To Mujawayo, this kind of statement, always identical (same phrases, same structure) is almost indecent because it does not express any regret or any personal responsibility: everyone is hiding his own behaviour behind “the group as such” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2004, p. 127). Many survivors confirm that not a single prisoner came and expressed remorse for what he did. In some cases, prisoners decided to confess their crimes, but they did it in a mechanical way, and even required the victims’ forgiveness—most often taken for granted. There are pressures in favour of forgiveness all around (from official authorities, churches, and NGOs); survivors discredit mainly what they consider as only pretence of forgiveness.

The absence of authenticity is apparent in many gestures leading theoretically to forgiveness: “Humanitarian organizations…. spend millions of dollars in order to make us forgiv[e] and bind each other by friendship. But survivors do not want to bargain their word against little compensations” (Hatzfeld 2007, p. 101). This account likewise illustrated the hollowness of the victim’s forgiveness in response to the hollowness of the perpetrator’s request for the same: “Two people came at home to ask me for forgiveness. They did not come willingly, but in order to avoid the prison. It is difficult to explain to a father how one has cut his daughter or for the father to ask these people how they have cut her. Then, we did not say anything but polite phrases…. To listen to them or not to listen to them was the same[.] I listened to them in order [for] them to go away quicker[,] letting me alone with my grief. When they left, the persons added that they had been kind with me since they missed me in the marshes. Me, I pretended to thank them” (Hatzfeld 2007, p. 104).

This strategy, used largely by criminals to avoid too many years in prison, creates an overwhelming sense of injustice in the victims. In some cases, as the former prisoner Elie Mizinge explains, perpetrators even regret not having “finished their job. They blame themselves for negligence, more than for spitefulness. . . . Waiting to start again” (Hatzfeld 2003, p. 198). However, the external pressure is perceived as so intense that some survivors tend to internalize a certain obligation to forgive. As another victim said to her former perpetrator, “The government forgave you and I cannot refuse it to you” (Penal Reform International 2005). Similarly, several other survivors explain that they agreed to forgive because the “power”—the State or the Church—asked them to do so (Hatzfeld 2007, p. 19).

4.4.3 A Global Distance from Any ‘Politics of Reconciliation’

In Rwanda, as well as in other places, like South Africa, forgiveness has been publicly encouraged as the only, or at least as the most important, condition for reconciliation. Unsurprisingly, the resistance of many victims to public pleas for forgiveness can seep into a more general animosity against the process of reconciliation. Many survivors denounce the so-called “politics” or “ideology” of reconciliation: “Reconciliation. This word became unbearable to me and to most of the survivors who[m] I know. To me, it is even perfectly indecent after a genocide . . . . “To reconcile,” as it is written in the dictionary, consists in making people at odds agree again. . . . Do I have to consider that what happened in Rwanda between April and July 1994 is the product of a dispute, a quarrel, a disagreement[,] and therefore that it would not be understandable not to reconcile? Do the people who use this word all the time realize that its meaning is fundamentally simplistic?” (quoted by Braeckman 2004).

Moreover, the public advocacy of forgiveness and reconciliation is permeated with promises of healing, peace, and harmony. At this juncture, forgiveness and reconciliation can take on the quality of a temptation, a lure of redemption. The words of Mujawayo on this point are univocal: “I really hope that I will not give in to in the “national reconciliation” camp…. To have a grudge against somebody requires an important mental resistance: you are thinking about it all the time and this feeling consumes you so much that, just to appease it a little bit, you sometimes find yourself having the temptation to forgive. If, furthermore, governmental politics presents forgiveness as a national priority…, I do fear the easiness of such project: all of us would be beautiful, we would finally have become nice, everything would be well cleaned and then, that would start again! But what would start again in fact?” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2006, p. 17).

Beyond this general resistance to any official ‘politics of reconciliation,’ Mujawayo is ready to conceive a gradual rapprochement, on a people-to-people level, among Rwandans. If she refuses to forgive, literally, she does not totally reject the concept of reconciliation “because there is no other possible choice”: “All those I met in Rwanda, until the survivors working on the field,… never think about forgiveness… However, all of them work in favour of reconciliation. Because to reconcile does not mean to forgive. To take up with neighbours again, starting with the ability to greet each other, is important for all the reasons that I have already emphasized: our culture cannot be conceived without these traditions, these rituals” (Mujawayo and Belhaddad 2006, pp. 130–131).

The record of Esther Mujawayo manifests the unavoidable tension between the need to look forward and the absolute necessity of respecting the intimate experience and personal pace of each survivor. In this regard, the challenge is paramount. As Mujawayo emphasizes, “[T]his is not the end of the genocide that really stops a genocide, because inwardly genocide never stops” (2004, p. 197). The same experience is echoed in the words of another survivor: “The survivor remains inconsolable. He resigns himself but he remains in revolt and powerless. He does not know what to do, the social environment does not understand him, and he does not understand himself either” (Mukayiranga 2004, p. 777).

4.5 Conclusion

As each of these voices reminds us, there is a strong need for a sustained and extensive ethical reflection on the advocacy and practice of reconciliation in the aftermath of mass atrocities. This article intended to address just one small part of this more-comprehensive undertaking. Its objective was to bring more nuances to common conceptions of unforgiving victims. As we have seen, forgiveness is not an absolute virtue but a personal choice. That means that ‘unforgiving-ness’ is not systematically the sign of some kind of moral failure (Brudholm 2008). Knowing that, how can we understand the triumph of the ‘resilience – reconciliation – redemption’ triptych among Western donors, practitioners and even scholars? Three main reasons can be mentioned to understand this phenomenon. First, the ‘reconciliation narrative’ is an uncomplicated story line. The simplicity and clarity of its message makes it particularly effective in a 5 min discussion in the corridors of the American Congress or in a 2 min presentation on CNN (Autesserre 2012). The plot is well known. It nicely resonates with the Christian precepts, as well as with the personal development market that preaches the constant reinvention of one-self, whatever the horrors of the past.

Second, the ‘reconciliation narrative’ reassures us. Like in a fairy tale, its characters overcome violence, turn the dark page and move on. Far from being stuck and oppressed by festering wounds, survivors and perpetrators are actively involved in their common healing process. In doing so, they implicitly make the promise that such a level of violence will never happen again. The success of the stories emphasized by the Forgiveness Project, a UK based charity, is symptomatic. The purpose of this project is to use real stories of victims and perpetrators in order to “encourage people to consider alternatives to resentment, retaliation and revenge”.Footnote 13 The Forgiveness Project website visitors are simply fascinated: “I am just overwhelmed…thank you so much for this wonderful page! I can’t stop reading and reading and reading”; “I have been reading your extraordinary website over several months and find the stories a marvellous reflection on how amazing the human spirit can be”; “This site cracked open my heart, and made me look at the world in general and my life in particular in a new way. Brace yourself. It may haunt you. The issue addressed here – forgiveness – could save our world. I am rarely as moved by a single site as I was by this one”; “I have spoken passionately about how I’ve been moved and inspired by the Forgiveness Project, and its challenging exploration – and celebration – of amazing personal stories of reconciliation and renewal from around the world” (The Forgiveness Project, Supporters).

These examples could easily be multiplied. Each of them indicates the attraction of testimonials “vibrating with humanity” (The Forgiveness Project, Supporters). The direct link between the specific context of each story (Rwanda, Northern Ireland, South Africa, to name a few) and the visitors’ private life is striking. The following testimony illustrates it very well: “I want to thank the project for sharing, for being available. I am going through something very difficult in my life right now. It’s as though I’m walking a mountain’s ridge; to one side lies the barren valley of anger, and to the other runs the river of forgiveness and inspiration. Through the on line stories, the project has helped my journey. Thank you” (The Forgiveness Project). These words of gratitude show that the reconciliation narrative is not only effective in the present but also useful regarding the future.

Third, the maximalist conception of reconciliation is much appreciated to deal with the past. It indeed relieves our need for closure. The vast majorities of the cases show that some consequences of mass atrocities are not only devastating, but also irreversible. However, the irrevocable is probably one of the most difficult realities to apprehend. It can therefore be tempting to diffuse the norm of reconciliation in an attempt to make the irreversible aspect of the criminal past reversible again. The recurrence of the notion of ‘redemption’ in the framework of the interviews made in Brussels and Washington undeniably confirms this trend.

These three reasons—need for efficiency, hope and closure—explain why the reconciliation narrative is so central. What is its impact? It is likely to be stimulating in the short term. Nonetheless, it can be vain and even counterproductive if people adapt it at all costs. In the long term, maximalist reconciliation advocates raise the victims’ expectations and take the risk of a backlash in terms of disillusion and bitterness (Backer 2010). Expecting full justice, complete truth and social harmony in the aftermath of mass atrocities inevitably provokes a high level of disappointment.

For a while, the stakeholders can play their role in the reconciliation scenario: criminals and accomplices are rehabilitated, bystanders are relieved, resilient victims become heroes, third parties mediate and gratifyingly ‘save’ the entire population. Like in a comedia dell’arte, all characters have a good reason to enthusiastically participate in the play. All characters but one: the unforgiving victim. In resisting, this voice disturbs the entire melody. The temptation to erase it is real. Left in the dark, the voice becomes weaker and weaker. However, this temptation is illusionary. In transforming post-conflict situations into a smooth process of redemption, this scenario does not grasp the complexity of the reality. Like the fool in Shakespeare’s pieces, the resisting voices allow the audience to keep in touch with reality, instead of hanging on to a fiction.

The metaphor of the comedia dell’arte does not cynically deny all the reconciliation efforts. On the contrary, it shows how decisive these efforts are if—and only if—they are realistic in terms of aims and in terms of timing. Research shows the possibility to work on the painful memories of the past in order to move forward (Rosoux 2004). The transformation of relationships between former enemies is imaginable, but it is not plausible in any circumstances and at any pace. Above all, it can never be imposed from outside. Mediation is by nature an extremely delicate exercise. Mediation after a war is a far more demanding challenge. To succeed, humanitarian workers need an extraordinary amount of determination and modesty. One distinction might be useful in order to adopt a just attitude: being doggedly optimistic does imply falling into the mythical and often mystical waters of reconciliation. In the aftermath of mass atrocities, the humanitarian task is a necessity—and not a myth.

Notes

- 1.

Gardner-Feldman (1999) distinguishes philosophical-emotional and practical-material components of reconciliation. In the same line, Long and Brecke (2003) analyse two main models of reconciliation: a signalling model and a forgiveness model. Hermann (2004) discerns cognitive, emotional-spiritual and procedural aspects of reconciliation. Nadler (2002) puts an emphasis on socio-emotional and instrumental reconciliation. Schaap (2005) emphasizes restorative and political reconciliation approaches. Galtung (2001) refers to no less than 12 different conceptions of reconciliation.

- 2.

Herman Van Rompuy, 1 July 2013, Zagreb.

- 3.

Ibidem.

- 4.

Filmed over the course of 3 years, Icyizere Hope is a documentary by filmmaker Patrick Mureithi about a reconciliation workshop in Rwanda that brings together ten survivors and ten perpetrators of the 1994 genocide (2009, 1 h 35, Josiah Film). As We Forgive is the 2008 student documentary film by Laura Waters Hinson (53 min, produced by Stephen Maceevety). The film tells the story of two Rwandan women who come face-to-face with the neighbours who slaughtered their families during the 1994 genocide. The documentary Ingando – when enemies return (2007, 33 min, Safari Gaspard) tells the story of the troublesome relationship between ex-combatants and genocide survivors. The film by Martin Bush Larsen and Jesper Houborg follows two former soldiers’ lives in the Ingando, and gives a voice to their thoughts and dreams of a positive return. In Raindrop over Rwanda, the American philanthropist Charles Annenberg Weingarten tours Rwanda with host Honore Gatera to uncover the tragedy of the 1994 genocide (2010, 23 min, Annenberg Foundation).

- 5.

See the website of As We Forgive.

- 6.

See the of As We Forgive documentary film.

- 7.

See the documentary Beyond Right and wrong: Stories of Justice and Forgiveness, The Forgiveness Project.

- 8.

In 2012 only, see the speeches made on 7 February, 30 March, 9 and 13 April, 16 May, 3 et 9 July. See the website http://www.presidency.gov.rw/, accessed 6 October 2014. The notion of resilience has also been chosen to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the independence of Rwanda. See in this regard the event “A journey of Resilience” organized on 30 June 2012 the Embassy of Rwanda in Washington.

- 9.

In 2012, see among others the speeches pronounced on 31 January, 1st and 21 May, 13 June, 31 August, 3 and 11 September.

- 10.

Interviews made in Washington between February and June 2011.

- 11.

See, for instance, the radio series produced by the Belgian NGO RCN—Justice et démocratie, “Si c’est là, c’est ici”, the impressive number of prizes won by the documentary film As we forgive or even the TV success of Immaculée Ilibagiza on CNN and CBS. The development of a real market in this field is also significant. See, for instance, the possibility to buy the ‘As we forgive movie event kit’ or the ‘4give T-shirt’ (during the screenings of the film and on line), the possibility to register for a conference, a retreat or even a pilgrimage (in Kibeho in Rwanda or in Banneux in Belgium) with Immaculée Ilibagiza. In 2012, the fees to participate in the Kibeho’s trip were 2,950$ (the price of the flight being not included). See http://www.immaculee.com, accessed 6 October 2014.

- 12.

This part of the chapter is based on a research carried out with Brudholm and Rosoux.

- 13.

All the stories can be read on the website of The Forgiveness Project.

References

Ackermann A (1994) Reconciliation as a peace-building process in postwar Europe. Peace Change 19(3):229–250

Arendt H (1961) Condition de l’homme moderne. Calmann-Lévy, Paris

Autesserre S (2012) Dangerous tales: dominant narratives on the Congo and their unintended consequences. Afr Aff 111(443):202–222

Backer D (2010) Watching a bargain unravel? A panel study of victims’ attitudes about transitional justice in Cape Town, South Africa. Int J Transit Justice 4:443–456

Bar-Siman-Tov Y (2000) Israel–Egypt peace: stable peace? In: Kacowicz A et al (eds) Stable peace among nations. Rowman and Littlefield, Boulder, pp 220–238

Bar-Siman-Tov Y (ed) (2004) From conflict resolution to reconciliation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bar-Tal D, Bennink G (2004) The nature of reconciliation as an outcome and as a process. In: Bar-Siman-Tov Y (ed) From conflict resolution to reconciliation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 11–38

Belfior S (2011) Declaration made in Kigali, 1st April 2011, http://www.presidency.gov.rw/home/1-latest-news/428-unity-is-strength-foundation-to-organize-international-peace-conference-in-rwanda. Accessed 6 Oct 2014

Braeckman C (2004) Rwanda, dix ans après. Politique Internationale 103:417

Brudholm T (2008) Resentment’s virtue: Jean Amery and the refusal to forgive. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, Philadelphia

Brudholm T, Rosoux V (2013) The unforgiving. Reflections on the resistance to forgiveness after atrocity. In: Hirsch A (ed) Theorizing post-conflict reconciliation: agonism, restitution and repair. Routledge, New York, pp 115–130

Crocker DA (1999) Reckoning with past wrongs: a normative framework. Ethics Int Aff 13(1):43–64

Galtung J (2001) After violence, reconstruction, reconciliation, and resolution. In: Abu-Nimer M (ed) Reconciliation, justice and coexistence. Theory and practice. Lexington Books, Lanham, pp 3–23

Gardner-Feldman L (1999) The principle and practice of ‘Reconciliation’ in German Foreign Policy: relations with France, Israel, Poland, and the Czech Republic. Int Aff 75(2):333–356

Goodman D (1997) Justice drowns in political quagmire. Mail and Guardian, 31/01

Graybill LS (2002) Truth and reconciliation in South Africa: miracle or model? Lynne Rienner, Boulder

Hatzfeld J (2003) Une saison de machettes. Seuil, Paris

Hatzfeld J (2007) La stratégie des antilopes. Seuil, Paris

Hermann TS (2004) Reconciliation: reflections on the theoretical and practical utility of the term. In: Bar-Siman-Tov Y (ed) From conflict resolution to reconciliation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 39–60

Ilibagiza I (2007) Left to tell: discovering god amidst the Rwandan holocaust. Hay House, New York

Kacowicz A et al (eds) (2000) Stable peace among nations. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham

Kayitesi B (2009) Demain ma vie. Enfants chefs de famille dans le Rwanda d’après. Editions Laurence Teper, Paris

Lederach JP (1998) Beyond violence: building sustainable peace. In: Weiner E (ed) The handbook of interethnic coexistence. Continuum, New York, pp 236–245

Long WJ, Brecke PB (2003) War and reconciliation. Reason and emotion in conflict resolution. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Mamdani, M. (1997) When victims become killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Mujawayo E, Belhaddad S (2004) Survivantes. Rwanda, histoire d’un génocide. Éditions de l’Aube, La Tour-d’Aigues

Mujawayo E, Belhaddad S (2006) La fleur de Stéphanie. Entre réconciliation et déni. Flammarion, Paris

Mukayiranga S (2004) Sentiments de rescapés. In: Coquio C (ed) L’Histoire trouée. Négation et témoignage. L’Atalante, Nantes, pp 776–785

Nadler A (2002) Post resolution processes: an instrumental and socio-emotional routes to reconciliation. In: Salomon G, Nevo B (eds) Peace education: the concept, principles and practices around the world. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 127–143

Oppenheim G (2008) Acts of Reconciliation. Washington Post, 05/07

Penal Reform International (2005) Rapport de synthèse de monitoring et de recherche sur la gacaca, phase pilote janvier 2002 - décembre 2004, http://www.penalreform.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/rep-ga7-2005-pilot-phase-fr_0.pdf

Philpott D (ed) (2006) Politics of past evil: religion, reconciliation, and the dilemmas of transitional justice. University of Notre-Dame Press, Chicago

Rosoux V (2004) Human rights and the ‘Work of Memory’ in international relations. Int J Hum Rights 3(2):159–170

Rosoux V (2014) Réconciliation: les limites d’un conte de fée. In: Andrieu K, Lauvau G (eds) Quelle justice pour les peuples en transition? Presses universitaires de Paris Sorbonne, Paris, pp 113–126

Schaap A (2005) Political reconciliation. Routledge, London

Sémelin J (2005) Purifier et détruire. Usages politiques des massacres et génocides. Seuil, Paris

Shriver DW (1995) An ethic for enemies: forgiveness in politics. Oxford University Press, New York

Staub E (2000) Genocide and mass killing: origins, prevention, healing and reconciliation. Polit Psychol 21:367–362

Steward J (2009) Only healing heals: concepts and methods of psycho-social healing in post-genocide Rwanda. In: Clark P, Kaufman Z (eds) After genocide. Transitional justice, post-conflict reconstruction and reconciliation in Rwanda and beyond. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 171–189

Stover E, Weinstein HM (eds) (2004) My neighbor, my enemy: justice and community in the aftermath of mass atrocity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

The Forgiveness Project. http://theforgivenessproject.com/. Accessed 6 Oct 2014

Tutu D (1999) No Future without Forgiveness. Doubleday, New York

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rosoux, V. (2015). Post-Conflict Reconciliation: A Humanitarian Myth?. In: Gibbons, P., Heintze, HJ. (eds) The Humanitarian Challenge. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13470-3_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13470-3_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-13469-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-13470-3

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawLaw and Criminology (R0)