Abstract

Inborn errors of metabolism comprise a large class of genetic diseases involving disorders of metabolism. Presentation is usually in the neonatal period or infancy but can occur at any time, even in adulthood. Seizures are frequent symptom in inborn errors of metabolism, with no specific seizure types or EEG signatures. The diagnosis of a genetic defect or an inborn error of metabolism often results in requests for a vast array of biochemical and molecular tests leading to an expensive workup. However a specific diagnosis of metabolic disorders in epileptic patients may provide the possibility of specific treatments that can improve seizures. In a few metabolic diseases, epilepsy responds to specific treatments based on diet or supplementation of cofactors (vitamin-responsive epilepsies), but for most of them specific treatment is unfortunately not available, and conventional antiepileptic drugs must be used, often with no satisfactory success. In this review we present an overview of metabolic epilepsies based on various criteria such as treatability, age of onset, seizure type, and pathogenetic background.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

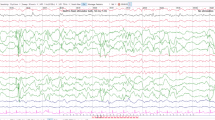

A very large number of inherited errors of metabolism (IEM) may occur with neurologic symptoms such as seizures, developmental delay, mental deterioration, cranial nerve deficits and movement disorders (Wolf et al. 2005). Epilepsy may dominate the clinical picture, especially in newborns and infants, or may be part of a larger clinical spectrum with other extraneurologic findings (osseous, cutaneous, visceral, endocrine, sensorial, and metabolic). Indeed, the presence of extraneurologic signs raises a strong probability of finding systemic metabolic disturbances (Wolf et al. 2009a, b). Epilepsy associated with IEM has usually the features of a “catastrophic encephalopathy” because seizures begin usually at early age, they are often refractory to conventional antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and epileptic activity is associated with severe cognitive, sensorial, and/or motor functions deterioration (Wolf et al. 2005, 2009a, b). Metabolic epileptic encephalopathies display an age dependent susceptibility and expression in the clinical phenotype. The seizure phenotype thus can be seen to evolve over time to fit descriptions of different epilepsy syndromes (Wolf et al. 2005). The EEG findings can be strikingly abnormal but they lack specificity and overlapping findings are frequent in different IEMs. EEG changes range from disorganized and slow background rhythms, focal and multifocal epileptiform patterns, generalized abnormalities as well as suppression-burst patterns (Wolf et al. 2005; Papetti et al. 2013; Fig. 1). The MRI findings may be normal or reveal associated structural abnormalities. MR spectroscopy is able to none invasively identify several metabolites peaks related to metabolic encephalopathies (Wolf et al. 2005). The diagnosis of metabolic disorders in epileptic patients may provide the possibility of specific treatments that can improve seizures. In a few metabolic diseases, epilepsy responds to specific treatments based on diet or supplementation of cofactors (vitamin responsive epilepsies), but for most of them specific treatment is unfortunately not available, and conventional antiepileptic drugs must be used, often with no satisfactory success (Wolf et al. 2009a, b). Neurometabolic epilepsies can be classified according to different criteria, i.e., type of biochemical defects and clinical presentation. More recently the age of onset of metabolic epilepsy has been considered for classification (Table 1; Papetti et al. 2013).

In this chapter we will focus on diseases and conditions where epilepsy is the predominant clinical manifestation and especially where the disease course can be positively influenced by specific metabolic therapies (Table 2; Papetti et al. 2013; Pascual et al. 2008).

Neonatal Onset Seizures

Vitamin B Response Epileptic Seizures

Pyridoxal phosphate (PSP), the active form of vitamin B6, is the cofactor for over 100 enzyme-catalyzed reactions in the body, including many involved in the synthesis or catabolism of neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine, serotonin, and inhibitory transmitter c-aminobutyric acid) (Gospe 2010) . Inadequate levels of pyridoxal phosphate in the brain cause neurological dysfunction, particularly epilepsy (Plecko and Stöckler 2009). Three genetic epilepsies are recognized to be cause PSP deficiency: Pyridoxine-dependent seizures, Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) dependent epilepsy and hypophosphatasia. They do so by different mechanisms: the first by inactivation, the second by blocking conversion of other forms of vitamin B6 to PLP, and the third by reducing transport into the brain and into cells (Baxter 2003).

Pyridoxine-dependent seizures (PDS) are due to an autosomal recessive inborn error of metabolism and they are characterized by neonatal seizures that are not controlled with anticonvulsants but that respond both clinically and electrographically to large daily supplements of pyridoxine (vitamin B6). The disorder may present within few hours of birth as an epileptic encephalopathy; sometimes intrauterine fetal seizures occur. Other cases may present with seizures at a later time during the first several weeks of life. In rare instances, children with this condition do not have seizures until before 2 years of age, and these are considered to be late-onset cases (Gospe 2010) . Affected newborn typically experience prolonged seizures which either recur serially or evolve into status epilepticus. Seizures generally include partial seizures, generalized tonic clonic seizures (GTCS), spasms and myoclonus. Additional features of pyridoxinedependent epilepsy include hypothermia, poor muscle tone, and neurodevelopment disabilities (Plecko and Stöckler 2009). These patients are not pyridoxine-deficient, but they are metabolically dependent on the vitamin, so that the institution of either parenteral or oral pyridoxine rapidly results in seizure control and improvement in the encephalopathy (Gospe 2010). The EEG is usually severely abnormal and the possible patterns include burst suppression, hypsarrhytmia and multiple spike-wave discharges (Fig. 2, Nabbout and Dulac 2008; Papetti et al. 2013). Imaging may be normal or may demonstrate cerebellar dysplasia, hemispheric hypoplasia or atrophy, neuronal dysplasia, periventricular hyperintensity or intracerebral hemorrhage (Baxter 2003).

PDS is caused by mutations in the ALDH7A1 gene that encodes the protein antiquitin (a-aminoadipic semialdehyde dehydrogenase), that functions within the cerebral lysine catabolism pathway (Scharer et al. 2010) . The deficient activity of antiquitin results in the accumulation of a-aminoadipic semialdehyde (AASA) and piperideine-6-carboxylic acid (P6C). The P6C was shown to inactivate pyridoxalphosphate (PLP), the active vitamer of pyridoxine, by a Knoevenagel condensation reaction, leading to severe secondary PLP deficiency. The PLP is a cofactor of various enzymes in the central nervous system, so that seizures in PDS are due to a decrease in GABA levels in the brain with an imbalance between the excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters (Mill et al. 2010; Scharer et al. 2010).

Diagnosis may be made by concurrently administering pyridoxine (100 mg) intravenously while monitoring the EEG, oxygen saturation, and vital signs. In individuals with PDS, clinical seizures generally cease over several minutes. If a clinical response is not demonstrated, the dose should be repeated up to a maximum of 500 mg. An alternate diagnostic approach is suggested for patients who are experiencing frequent short anticonvulsant-resistant seizures. In those cases, oral pyridoxine (up to 30 mg/kg/day) should be prescribed, and patients with PDS should have a resolution of clinical seizures within 3–7 days. Biochemical tests include measurement of the specific biomarker a-AASA and pipecolid acid (PA) in the urine, plasma and CSF. Molecular genetic testing of ALDH7A1 is also recommended as confirmatory testing (Gospe 2010). When the diagnosis of PDS is established, the lifelong therapy with pyridoxine should be instituted. The daily administration of 50–200 mg (given once daily or in two divided doses) is generally effective in preventing seizures in most patients (Gospe 2010).

Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP) dependent epilepsy is characterized by neonatal seizures refractory both to conventional AEDs and pyridoxine administration (Kuo and Wang 2002). Instead, individuals with this type of epilepsy are responsive to large daily doses of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (30 mg/kg/day in three or four divided doses enterally) (Hoffmann et al. 2007). PLP dependent epilepsy is inherited with an autosomal recessive pattern. The gene involved is the PNPO gene that encodes an enzyme called pyridoxine 50-phosphate oxidase involved in the conversion of vitamin B6 derived from food (in the form of pyridoxine and pyridoxamine) to the active form of vitamin B6 that is PLP (Mills et al. 2005) .

Affected babies are usually born prematurely and may have immediate signs of encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia. Clinical seizures may consist of myoclonus, clonic movements and ocular, facial and other automatisms (Baxter 2010). Untreated, the disorder results either in death or in profound neurodevelopment impairment. In treated patients, particularly those in whom the disorder was recognized early, near normal development may be possible (Bagci et al. 2008).

CSF and urine analyses in affected children show evidence of secondary deficiencies of several PLP dependent enzymes including aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (decreased CSF concentrations of homovanillic acid and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and increased l-DOPA and 3-methoxytyrosine as well as increased urinary concentrations of vanillactic acid) (Plecko and Stöckler 2009).

Chronic therapy for confirmed PLP dependent epilepsy consists of administration of PLP 30–50 mg/kg/day divided in four to six doses (Plecko 2005).

Hypophosphatasia is an inherited disorder that affects the development of bones and teeth. However it can also led to PDS in neonates as pyridoxal phosphate is not dephoshorilated and therefore cannot cross membranes (Plecko 2005). Biochemically, this disorder consists of deficient activity of the tissue non-specific isoenzyme of alkaline phosphatase. The enzymatic deficiency results from mutations in the liver/bone/kidney alkaline phosphatase gene ALPL. Laboratory diagnosis is confirmed by reduced levels of serum alkaline phosphatase, and raised levels of urinary phosphoethanolamine (PEA) (Balasubramaniam et al. 2010).

Folinic acid-responsive seizures are characterized by cessation of seizures after administration of folinic acid (3–5 mg/kg/day enterally, for 3 to 5 days) (Plecko 2005). Only a few affected infants were published. Patients present with seizures, either myoclonic or clonic, apnea and irritability within 5 days after birth (Gallagher et al. 2009). A characteristic pattern of peaks, reflecting two unidentified compounds, was recognized in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) when analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPCC) with electrochemical detection to quantify monoamine metabolites. Recently, it has been demonstrated that folinic acid responsive seizures are also caused by mutations in ALDH7A1 and therefore should be treated with adequate doses of pyridoxine. Whether additional treatment of these children with folinic acid is of added benefit, remains to be shown (Gallagher et al. 2009).

Disorders of Amino Acid Metabolism

Some disorders of amino acid metabolism such as nonketotic (NKH), methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) deficiency, GABA transaminase deficiency, serine deficiency, and congenital glutamine deficiency, can also give rise to this epileptic syndrome, each with its specific biochemical traits (Wolf et al. 2009a, b).

Nonketotic hyperglycinemia (NKH) is a metabolic disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance, causing severe, frequently lethal, neurological symptoms in the neonatal period. NKH derives from a defect of a larger enzyme complex, known as glycine cleavage enzyme (GCS) that is responsible for the glycine degradation. When glycine cleavage enzyme is defective, excess glycine can build up to toxic levels in the body’s organs and tissues (Applegarth and Toone 2004). The three genes known to be associated with glycine encephalopathy are: GLDC (encoding the P-protein component of the GCS complex and accounting for 70–75 % of disease), AMT (encoding the T-protein component of the GCS complex and accounting for ~ 20 % of disease), and GCSH (encoding the H-protein component of the GCS complex and accounting for < 1 % of disease) (Hamosh et al. 2009).

The majority of glycine encephalopathy presents in the neonatal period (85 % as the neonatal severe form and 15 % as the neonatal mild form). Of those presenting in infancy, 50 % have the infantile mild form and 50 % have the infantile severe form (Rossi et al. 2009). Patients with classical neonatal NKH present in the first days of life with seizures or with encephalopathy, abnormal jerking movements, lethargy and severe hypotonia. Affected newborns will have repeated episodes of severe and prolonged apnea that require ventilatory support. Hiccuping is frequent and brain ultrasound scans may show defects of the corpus callosum (Hamosh et al. 2009). Epilepsy associated with NKH may reflects the early myoclonic encephalopathy (EME) with erratic or fragmentary myoclonus, simple focal seizures, focal tonic seizures, and tonic spasms, generally after 1 month of age and with an EEG patter of burst-suppression (SB) and progression towards hypsarrhytmia (Rossi et al. 2009). Untreated, the neonatal form of non-ketotic hyperglycinaemia is associated with death in the first months of life. Therapy with sodium benzoate and dextromethorphan may be helpful in some milder forms of the disease, alongside AEDs and general supportive care. The epilepsy remains drug resistant, infantile spasms may emerge, and the EEG evolves to hypsarrhythmia or multifocal discharges on a back- ground without normal activity. Atypical neonatal form of NKH can be similar to classical NKH, with hypotonia and apnea episodes that may require assisted ventilation, though seizures are less severe. Subsequently psychomotor development is significantly better than in the majority of patients with the classical NKH (Dinopoulos et al. 2005).

Atypical variants of NKH include also the infantile and late onset forms. Children with this condition develop normally until they are about 6 months old, when they experience delayed development and may begin having seizures. As they get older, many develop intellectual disability, abnormal movements, and behavioral problems. The late onset form is less common and more heterogeneous. The clinical presentation is after the second birthday and even during adulthood, mainly with mild cognitive decline and behavioral problems (Hamosh et al. 2009).

Transient neonatal hyperglycinemia (TNH) is characterized by elevated plasma and CSF glycine levels at births that are normalized within 2–8 weeks. TNH is clinically and biochemically indistinguishable from typical nonketotic hyperglycinemia at onset (Dinopoulos et al. 2005). The biochemical hallmark of NKH is increased glycine concentration in the plasma and, to an even greater extent, in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), with an abnormally high ratio between CSF and plasma levels. Confirmatory tests include enzymatic analysis in liver tissue and/or mutation analysis (Pascual 2003). Some babies have structural brain abnormalities evident on MRI, apparently as a result of the toxic effect of glycine on the developing brain. Treatment consists of reducing the intake of glycine and serine as well as improving its elimination by administering benzoate and by exchange transfusion (Pascual 2003).

Defects in the synthesis of L-serine lead to a syndrome of congenital microcephaly, neurodevelopmental disability, and epilepsy which may have neonatal onset (Pearl 2009). Two serine-deficiency syndromes have been described, namely 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (3-PGDH) deficiency and 3-phosphoserine phosphatase (3-PSP) deficiency (de Koning and Klomp 2004). The 3-PGDH deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by neurological symptoms which dominate the clinical phenotype (i.e., microcephaly, seizures, and neurodevelopmental delay). Seizures either started as generalized tonic clonic seizures or as flexor spasms with West syndrome. In older patients, diagnosed at ages 5–9, tonic, atonic and myoclonic seizures as well as absences were described (Tabatabaie et al. 2010). The EEG of patients with 3-PGDH showed hypsarrhytmia or severe multifocal epileptic abnormalities with poor background activity (de Koning and Klomp 2004). The 3-PGDH gene is located on chromosome 1q12. Two different homozygous missense mutations were described. Both mutations lead to a significant reduction of enzyme activity after expression of the mutant enzymes in vitro (de Koning and Klomp 2004). Low concentrations of serine and, to a variable degree, of glycine in plasma and CSF, are the biochemical hallmark of the disease. Oral supplementation of l-serine is proved to be very effective in the treatment of seizures (Tabatabaie et al. 2010).

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a disorder of phenylalanine metabolism that frequently results in epilepsy if a dietary restriction was not implemented at birth (Blau et al. 2010). Classical PKU is an autosomal recessive disorder, caused by mutations in both alleles of the gene for phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), found on chromosome 12. In the body, phenylalanine hydroxylase converts the amino acid phenylalanine to tyrosine. As consequence of mutations in both copies of the gene for PAH, the enzyme is inactive or is less efficient, and the concentration of phenylalanine in the body can build up to toxic levels. In some cases, mutations in PAH will result in a phenotypically mild form of PKU called hyperphenylalanemia. Both diseases are the result of a variety of mutations in the PAH locus; in those cases where a patient is heterozygous for two mutations of PAH (i.e., each copy of the gene has a different mutation), the milder mutation will predominate (Blau et al. 2010). A small minority of PKU cases results from defects in the metabolism of tetrahydrobiopterin, the obligate cofactor of PAH. The symptoms of untreated PKU, which manifest primarily in the brain, are diverse, and can range from mild cognitive impairment to severe mental retardation, with motor impairment and pyramidal signs (Martynyuk et al. 2007). Refractory epilepsy is common, with infantile spasms or GTCs; PKU has been also reported in patients with West syndrome. At present, for almost all patients with phenylketonuria, diagnosis and the start of treatment result from neonatal screening rather than clinical symptoms. Treatment consists of dietary restriction and l-dopa, 5-hydroxytryptophan and folinic acid supplements (Martynyuk et al. 2007).

Urea Cycle Disorders

Urea cycle disorders (UCD) represent a group of inborn errors of metabolism result from single gene defects involved in the detoxification pathway of ammonia to urea (Zhongshu et al. 2001). The components of the pathway are: carbamyl phosphate synthase I (CPSI); ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC); argininosuccinic acid synthetase (ASS); argininosuccinic acid lyase (ASL); arginase (ARG) and the cofactor, N-acetyl glutamate synthetase (NAGS). Deficiencies of CPSI, ASS, ASL, NAGS, and ARG are inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. OTC deficiency is inherited in an X-linked manner (Braissant 2010; Summar 2005). Infants with a UCD often appear normal initially but rapidly develop cerebral edema and the related signs of lethargy, anorexia, hyperventilation or hypoventilation, hypothermia, seizures, neurologic posturing, and coma. In milder (or partial) UCD, ammonia accumulation may be triggered by illness or stress at almost any time of life, resulting in multiple mild elevations of plasma ammonia concentration; the hyperammonemia is less severe and the symptoms more subtle. In individuals with partial enzyme deficiencies, the first recognized clinical episode might be delayed for months or years (Braissant 2010). Seizures are frequent during the early stages of hyperammonaemia, especially in newborns. The EEG may show variable pattern of epileptic discharge, i.e., multifocal independent spike- and sharp-wave discharges, repetitive paroxysmal activity, unusually low-voltage fast activity, and findings consistent with complex partial seizures (Summar 2005). In late-onset UCD cases, EEG may show continuous semirhythmic activity with sharp components, leading to diagnosis of complex partial status epilepticus (Gropman et al. 2007).

The therapy of UCD include dialysis to reduce plasma ammonia concentration, intravenous administration of arginine chloride and nitrogen scavenger drugs to allow alternative pathway excretion of excess nitrogen, restriction of protein for 24–48 h to reduce the amount of nitrogen in the diet, providing calories as carbohydrates and fat reduce catabolism, and physiologic stabilization with intravenous fluids and cardiac pressors to reduce the risk of neurologic damage (Clague 2002).

Organic Acidemias

Organic acidemias (OA) consist of a group of disorders characterized by the excretion of non-amino organic acids in urine. Most organic acidemias result from dysfunction of a specific step in amino acid catabolism, usually the result of deficient enzyme activity. The majority of the classic organic acid disorders are caused by abnormal amino acid catabolism of branched-chain amino acids or lysine. The main types of OA include maple syrup urine disease (MSUD), propionic acidemia, methylmalonic acidemia, isovaleric acidemia and glutaric acidemia type I (GA-1) (Clague and Thomas 2002).

A neonate affected with an OA is usually well at birth and for the first few days of life. The usual clinical presentation is that of toxic encephalopathy and includes vomiting, poor feeding, neurologic symptoms such as seizures and abnormal tone, and lethargy progressing to coma. Outcome is enhanced by diagnosis and treatment in the first 10 days of life. In the older child or adolescent, variant forms of the OAs can present as loss of intellectual function, ataxia or other focal neurologic signs, Reye syndrome, recurrent ketoacidosis, or psychiatric symptoms (Van Gosen 2008; Seashore 2009).

MSUD (OMIM 248600) is caused by a deficiency of the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex (BCKDC). The mammalian BCKD complex consists of three catalytic components: E1, E2, and E3, and two regulatory enzymes. Mutations in these regions lead to the accumulation of three branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) and their toxic by-products in the blood and urine. The major clinical features of maple syrup urine disease are mental and physical retardation, feeding problems, and a maple syrup odor to the urine (Rahman et al. 2013)

There are presently five known clinical phenotypes for MSUD: classic, intermediate, intermittent, thiamin responsive, and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (E3)-deficient, based on severity of the disease, response to thiamin therapy, and the gene locus affected (Wang et al. 2003).

Classic MSUD is the most frequent form and the affected newborns appear normal at birth, with symptoms developing between 4 and 7 days of age. The infants show lethargy, weight loss, metabolic derangement, and progressive neurologic signs of altering hypotonia and hypertonia, reflecting a severe encephalopathy. Seizures and coma usually occur, followed by death if untreated (Seashore 2009). The seizures can be of different types, with occasionally presenting with status epilepticus and early treatment may improve the prognosis (Wang et al. 2003). The EEG pattern is variable and it includes spikes, polyspikes, spike-wave complexes, triphasic waves, severe slowing and bursts of periodic suppression ad are not related to blood BCAA levels (Korein et al. 1994).

Propionic acidemia (PA) (OMIM 606054) is characterized by the accumulation of propionic acid due to a deficiency in Propionyl CoA Carboxylase, a biotin dependent enzyme involved in amino acid catabolism. Patients may present with vomiting, dehydration, lethargy, and encephalopathy. Among the neurological complication often observed, developmental delay, seizures, cerebral atrophy and EEG abnormalities have been the most prominent. Seizures generally have onset in the neonatal period and they may include focal seizures, spasms, and generalized tonic and myoclonic seizures (Haberlandt et al. 2009). In 40 % of affected children, generalized convulsions and myoclonic seizures develop in later infancy, and older children may have atypical absence seizures (Aicardi 2007). Photosensitivity and fever induced seizures have also been described at the beginning in patients with PA. Intractable seizures may develop. The EEG pattern is variable and it may show hypsarrhythmia, burst suppression and diffuses delta wave activity with generalized or focal temporal spikes during the encephalopatic phase. MRI usually reveals alterated signal in the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus. MRS shows decreased NNA and myo-inositol and increased glutamate/glutamine in the basal ganglia (Chemelli et al. 2000).

Glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA-1, OMIM 608801) is an autosomal recessive disease due to an inborn error of the metabolism of the amino acids lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan due to mutations in the glutarylcoenzyme. A dehydrogenase gene (GCDH), on chromosome 19p13.2 (McClelland et al. 2009). Clinical expression usually involves an acute encephalopathic episode in infancy, followed by the development of severe dystonia-dyskinesia. Seizures may occur at presentation in the context of acute encephalopathy, but ongoing seizures are not common in GA-1 unless accompanied by severe brain damage (McClelland et al. 2009). Many children may have sudden dystonic spasms that could be mistaken for seizures. Although chronic epilepsy is rare, glutaric aciduria type I patients may present with epileptic seizures that are difficult to control with first- or second-line anticonvulsants as the sole clinical feature (Cerisola et al. 2009). This disorder can be identified by increased glutaryl (C5DC) carnitine on newborn screening. Urine organic acid analysis indicates the presence of excess 3-OH-glutaric acid, and urine acylcarnitine profile shows glutaryl carnitine as the major peak (McClelland et al. 2009).

The brain MRI is helpful for the diagnosis. Atrophy or hypoplasia of the frontotemporal regions of the cerebral hemispheres, enlarged pretemporal middle cranial fossa subarachnoid spaces, and cyst-like dilatation of the Sylvian fissures are often early findings in glutaric acidemia type I with “batwing” or “box-like” fissures (Neumaier-Probst et al. 2004).

The aim of therapy in OA is to restore biochemical and physiologic homeostasis. Neonates require emergency diagnosis and treatment depending on the specific biochemical lesion, the position of the metabolic block, and the effects of the toxic compounds. Treatment strategies include: (1) dietary restriction of the precursor amino acids and (2) use of adjunctive compounds to (a) dispose of toxic metabolites or (b) increase activity of deficient enzymes. Decompensation caused by catabolic stress (e.g., from vomiting, diarrhea, febrile illness, and decreased oral intake) requires prompt and aggressive intervention (Seashore 2009).

Peroxisomal Disorders

Zellweger syndrome (ZS, OMIM 214100) may be responsible for epilepsy in the neonatal period. Individuals with ZS develop signs and symptoms of the condition during the newborn period. These infants experience hypotonia, feeding problems, hearing loss, vision loss, and seizures. Children with ZS also develop life-threatening problems in other organs and tissues, such as the liver, heart, and kidneys. They may have skeletal abnormalities, including a large space between the bones of the skull (fontanels) and characteristic bone spots known as chondrodysplasia punctata that can be seen with an X-ray (Rahman et al. 2013). Affected individuals have distinctive facial features, including a flattened face, broad nasal bridge, and high forehead. Children with ZS typically do not survive beyond the first year of life (Steinberg et al. 2003). Areas of polymicrogyria are often frontal or opercular, resulting in a focal EEG and seizure semiology, and there are often focal motor seizures (Takahashi et al. 1997). Mutations in the PEX1 gene are the most common cause of the Zellweger spectrum and are found in nearly 70 % of affected individuals. The other genes associated with the Zellweger spectrum each account for a smaller percentage of cases of this condition (Steinberg et al. 2003).

Infantile Onset Seizures

Biotin Response Epileptic Seizures

Characteristic organic aciduria, cutaneous and neurologic symptoms with frequent seizures are present in holocarboxylase synthetase (HCS) and biotinidase deficiencies (BTD). Both disorders in biotin metabolism lead to multiple carboxylase deficiency and respond dramatically to biotin therapy (Joshi et al. 2010) .

Biotinidase deficiency (BTD) (OMIM 253260) is an autosomal recessively inherited disorder in which the vitamin, biotin, cannot be appropriately recycled (Wolf 2011a, b). BTD is the only gene known to be associated with biotinidase deficiency. The BTD gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called biotinidase that removes biotin that is bound to proteins in food, leaving the vitamin in its free state. Mutations in the BTD gene reduce or eliminate the activity of biotinidase. Deficiency of BTD leads to decrease biotin available resulting in reduced conversion of apocarboxylases to holocarboxylases or multiple carboxylase deficiency (Wolf 2011a, b). This subsequently causes the accumulation of abnormally high concentrations of toxic metabolites (Pindolia et al. 2010). Profound biotinidase deficiency results when the activity of biotinidase is reduced to less than 10 % of normal. Partial biotinidase deficiency occurs when biotinidase activity is reduced to between 10 and 30 % of normal (Thoene and Wolf 1983). If untreated, young children with profound BTD deficiency usually exhibit neurologic abnormalities including seizures, hypotonia, ataxia, developmental delay, vision problems, hearing loss, and cutaneous abnormalities (Bhardwaj et al. 2010). Seizures are the presenting symptom in 38 % of patients with biotinidase deficiency and are found in up to 55 % of patients at some time before treatment. Seizures often start after the first 3 or 4 months of life, and often as infantile spasms or GCTS (tonic-clonic, clonic and myoclonic). The refractory seizures respond promptly to small doses of biotin (5–20 mg/day) (Zempleni et al. 2008) .

Holocarboxylase synthetase (HCS) deficiency is an inherited disorder in which the body is unable to use the vitamin biotin effectively. Mutations in the HLCS gene cause holocarboxylase synthetase (Suzuki et al. 2005). The signs and symptoms of holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency typically appear within the first few months of life, but the age of onset varies. Symptoms are very similar to biotinidase deficiency and treatment (large doses of biotin) is also the same. Seizures are less frequent, occurring in 25–50 % of all children (Pascual et al. 2008).

Disorders of Creatine Metabolism

Creatine deficiency syndromes represent a group of inborn errors of creatine metabolism that is responsible for mental retardation, language delay and early-onset epilepsy (Nasrallah et al. 2010). Three inherited defects in the biosynthesis and transport of creatine have been described. The biosynthetic defects include deficiencies of the enzymes l-arginine–glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT) and guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (GAMT) (Nasrallah et al. 2010). The third is the deficiency of the creatine transporter 1 (CT1). Epilepsy is one of the main symptoms in two of these conditions, GAMT and CT1 deficiency, whereas the occurrence of febrile convulsions in infancy is a relatively common presenting symptom in all (Leuzzi 2002).

Clinical presentation of GAMT deficiency is usually characterized by normal developmental milestones in the first months of life, which can be abruptly discontinued by arrest/regression of psychomotor development with or without seizures. arrest/regression of psychomotor development with or without seizures. Epilepsy is the second most frequent symptom in GAMT deficiency after intellectual disability. Febrile seizures have often been reported in the early phase of the disease occurring during the first 24 months of life (mainly 3–6 months). The pattern of seizures is not consistent, and more than one type of seizures can occur in the same patient at different ages. Life-threatening tonic seizures with apnea or myoclonic seizures can be observed in the first months of life, whereas myoclonic astatic seizures, generalized tonic–clonic seizures, partial seizures with secondary generalization, drop attacks, absences, and staring episodes appear in early infancy or in adolescence. Febrile seizures, generalized tonic–clonic seizures, and myoclonic astatic seizures are the most commonly reported seizure types. No typical electroencephalography (EEG) pattern can be defined in GAMT deficiency. An early derangement of background organization and interictal multifocal spikes and slow wave discharges are frequently recorded. Focal EEG abnormalities, with a prominent involvement of frontal regions, have also been reported. Severe epilepsy has been reported in almost all cases. Movement disorders, such as athetosis, chorea, choreoathetosis, ballismus, and dystonia may be present (Leuzzi 2002).

The most typical neuroimaging alteration in GAMT deficiency is represented by bilateral pallidal lesions (hypointensity in T1-weighted and hyperintensity in T2-MRI images). In a few cases the lesion extended in the brainstem and selectively involved the white matter of the floor of fourth ventricle or the posterior pontine region (Leuzzi et al. 2013).

Biochemical findings associated with GAMT deficiency include the following: (1) reduced concentration of creatine in plasma, urine, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), muscle, and brain; and (2) marked increase of guanidinoacetic acid (GAA) in all the biologic fluids, mainly in the CSF. High values of GAA can be detected also in dry blood spot since the first days of life. A mild increase of GAA over the normal range has been detected in blood and/or urine of some carriers of GAMT gene mutations. GAMT enzyme activity may be tested in liver tissue, skin fibroblasts, and lymphoblasts. The aim of treatment is to correct both the depletion of creatine/creatine-phosphate pools and the accumulation of GAA. In GAMT deficiency, a lifelong oral supplementation with high doses of creatine monohydrate (350 mg/kg/day–2 g/kg/day) has been shown, by plasma creatine assessment (muscle creatine pool) and brain H-MRS (brain creatine pool), to replenish body creatine pools. A further abating effect on AGAT activity can be obtained through a dietary restriction of arginine (15 mg/kg/day) coupled with ornithine supplementation (ornithine aspartate 350–800 mg/kg/day). Medicaments such as sodium benzoate and phenylbutyrate, which remove arginine and glycine, respectively, have also been proposed according to a similar substrate inhibition approach. Among the different clinical manifestations of GAMT deficiency, epilepsy is by far the most responsive to treatment (Nasrallah et al. 2010; Verhoeven et al. 2005).

CT1 deficiency is one of the main causes of X-linked mental retardation in males, and it is caused by SLC6A8 gene mutations. Mental retardation and specific language derangement (oral-verbal dyspraxia of speech) are, in fact, the core symptoms of the disease. CT1 deficiency. It is rarely severe and it is usually responsive to conventional antiepileptic drugs . Its onset ranges between 16 months and 12 years. Febrile convulsions represent the first seizure-type in a number of subjects, and in a single case they led to subcontinuous generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Seizure pattern and EEG alterations can be extremely variable. Seizure-types include myoclonic seizures, generalized tonic–clonic seizures, convulsive status epilepticus, and partial seizures with secondary generalization. EEG recordings include normal tracing, diffuse slowing, aspecific sharp abnormalities, and focal/generalized paroxysmal or slow abnormalities, with or without sleep activation (Leuzzi et al. 2013). However, paroxysmal abnormalities are generally less severe as the child grows older. SLC6A8 genotype is not associated with epilepsy, as exemplified by personal observations and cases from the literature. Neuroimaging and clinical features suggest in some patients a possible perinatal ischemic insult. This aspect may be confounding from the diagnostic point of view because clinical history rarely justifies this suspect. However, these lesions are congruent with the concept of creatine as a protective factor against potentially ischemic damage. Their possible role in the determinism of epilepsy needs to be elucidated. There are a few clinical reports on females carrying SLC8A6 gene mutations. When symptomatic, they express a milder phenotype, including mild intellectual disability, behavioral disorders, problems of language development, learning difficulties, impairment of visual-constructional and fine motor skills, mild cerebellar symptoms, and constipation. Late occasional epileptic seizures have been described but not systematically studied (Leuzzi 2002).

The main biochemical alteration of patients with CT1 defect is the lack of brain creatine on H-MRS. Creatine is one of the major peaks in proton MR spectroscopy and is almost absent in all disorders of creatine synthesis and transport (Leuzzi 2002).

The urinary ratio creatine/creatinine (Cr/Crn) was proposed and confirmed as diagnostic marker of the disease. Diagnostic urinary Cr/Crn ratio ranged from 1.4 to 5.5 (reference values 0.006–1.2 in children under 4 years, 0.017–0.72 in patients between 4 and 12 years, 0.011–0.24 after 12 years of age). However, urinary Cr/Crn may be influenced by various nutritional and individual factors (Verhoeven et al. 2005).

Fibroblast and lymphoblast express SLC6A8 gene, and creatine uptake can be tested in these cells in patient with suspect CT1 defect. In contrast, muscle creatine is normal on both biochemical and H-MRS examination. No key clinical and/or neuropsychological cues have been identified to suggest the diagnosis of CT1 deficiency in girls with epilepsy and intellectual disability or learning difficulties. For these reasons gene sequencing seems to be the best diagnostic tool for females with a clinical suspect of CT1 (Verhoeven et al. 2005).

No effective treatment is available for males with CT1 defect. The supplementation of creatine, also at high dosages, does not improve H-MRS detectable brain creatine pool and/or clinical status. In contrast, creatine, as well as creatine precursor, supplementation is potentially effective in symptomatic females where the defect of CT1 is partial (Leuzzi et al. 2013).

Diagnosis is based on concentration of creatine and its precursors, measurement of enzyme activity for AGAT and GAMT, creatine uptake test for the diagnosis of CT1 defect, and mutation analysis.

The AGAT and GAMT deficiencies are inherited as an autosomal recessive trait; the SLC6A8 deficiency is X-linked inherited. In humans, the AGAT protein is encoded by the gene GATM (15q21.1). The human GAMT gene is located on chromosome 19p13.3, while the gene CT1 (alias CRTR, SLC6A8) has been mapped to chromosome band Xq28 (Nasrallah et al. 2010).

Disorders of GABA Metabolism

Amino butyric acid (GABA) metabolism is associated with several disorders, including GABA-transaminase deficiency, and succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency (SSADH) (Wolf et al. 2005).

GABA-transaminase deficiency is a rare disease with only few reported cases and it is characterized by abnormal development, seizures, and high levels of GABA in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (Jaeken 2002).

SSADH deficiency is an uncommon autosomal recessively inherited neurotransmitter disease involving GABA degradation. ALDH5A1 is the only gene currently known to be associated with SSADH deficiency. SSADH is an enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of succinate semialdehyde to succinate, the second and final step of the degradation of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. Clinical manifestations in patients with SSADH deficiency are varied, and may range from mild mental retardation, speech delay, or behavioral problems, to severe psychomotor retardation with intractable seizures (Pearl and Gibson 2004).

Approximately half of patients with SSADH deficiency have epilepsy, usually with GTCS and also atypical absence and myoclonic seizures. The EEG may reveal background slowing and disorganization as well as diffused and multifocal epileptiform abnormalities. MRI shows increased T2-weighted signal involving the globus pallidi bilaterally and symmetrically, in addition to the cerebellar dentate nuclei and subthalamic nuclei (Pearl et al. 2007).

Vigabatrin, an irreversible inhibitor of GABAtransaminase, inhibits the formation of succinic semialdehyde and thus is one of the most widely prescribed AEDs in this disorder (Matern et al. 1996). However, vigabatrin has shown inconsistent results and MRI signal changes have been observed in patients treated with high doses (Pearl et al. 2009).

Glucose Transporter Deficiency

Glucose Transporter 1 (GLUT1) is a membrane transporter that facilitates glucose transport across the blood–brain barrier. GLUT1 deficiency syndrome (OMIM #606777) is disorder that primarily affects the brain. Glucose transporter-1 (GLUT1) is encoded by SLC2A1 gene and usually mutations occur de novo, although the disease can also be inherited as autosomal dominant trait (Brockmann 2009). GLUT1 is highly expressed in the endothelial cells of erythrocytes and the blood–brain barrier and is exclusively responsible for glucose transport into the brain (Vannucci et al. 1997). Its deficiency leads to low glucose concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid (hypoglycorrhachia) (not associated with hypoglycaemia), in combination with a low to normal lactate in the cerebrospinal fluid. The classic patient with GLUT1 deficiency syndrome generally has drug resistant seizures beginning in the first year of life (Seidner et al. 1998).

Babies with GLUT1 deficiency syndrome have a normal head size at birth, but growth of the brain and skull is often slow, in severe cases resulting in microcephaly (Rotstein et al. 2010). Patients present with early-onset epilepsy, developmental delay, and a complex movement disorder as hypotonia, spasticity, ataxia and dystonia (Klepper and Leiendecker 2007; Schneider et al. 2009). The phenotype is highly variable and several atypical variants have been described (Klepper 2008). Seizures begin between age 1 and 4 months in 90 % of cases. Apneic episodes and abnormal episodic eye movements simulating opsoclonus may precede the onset of seizures by several months. Five seizure types occur: generalized tonic or clonic, myoclonic, atypical absence, atonic, and unclassified (Wang et al. 2009). The interictal EEG may be normal. The ictal EEG may show focal slowing or discharges, including 2.5–4 Hz spike and wave. A striking difference between pre- and postprandial EEG may be seen, with a decrease in epileptic discharges following carbohydrate intake. GLUT1 deficiency is now known to be a cause of drug-resistant childhood absence epilepsy and of adult-onset absence epilepsy with a normal CSF glucose. Patients with a non-classical phenotype have been described, characterized by developmental delay and movement disorders without epilepsy or familial and sporadic paroxysmal exercise induced dyskinesia with or without epilepsy (Overweg-Plandsoen et al. 2003; Friedman et al. 2006; Klepper and Leiendecker 2007; Suls et al. 2008).

When GLUT1 deficiency syndrome is suspected, a lumbar puncture in the fasting state should be performed. Diagnosis is made by documenting CSF glucose levels below 40 mg/dl (2.5 mmol/l) and low CSF/blood glucose ratio (< 0.50). CSF lactate is normal or low. The degree of hypoglycorrhacia and absolute ‘cut-off’ for a diagnosis of GLUT1 deficiency remain a source of debate, and mild clinical phenotypes have been reported with normoglycorrhacia and a normal CSF to blood glucose ratio; thus molecular genetic analysis of the SLC2A1 gene is considered the standard criterion for diagnosis. Approximately 80 % of patients harbour pathogenic mutations (Wang et al. 2009).

Epilepsy in GLUT1 deficiency is drug resistant and may be aggravated by fasting and by AEDs that inhibit GLUT1 (phenobarbitone, valproate, diazepam). The ketogenic diet is highly effective in controlling the seizures and is generally well tolerated. However, neurobehavioral and motor deficits persist in most cases. This high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet provides an alternative source of energy for the brain as ketone bodies, which are produced in the liver and which can easily penetrate the blood–brain barrier (Klepper 2008; Rahman et al. 2013).

Defects of Purine and Pyrimidine Metabolism

Adenylosuccinate lyase (ADSL) deficiency is an autosomal recessive defect of purine metabolism causing serious neurological and physiological symptoms. ASL catalyzes two distinct reactions in the synthesis of purine nucleotides, both of which involve the b-elimination of fumarate. The deficiency of ADSL results in the accumulation of succinylpurines in CFS, plasma and urine (Spiegel et al. 2006).

The human ADSL gene has been mapped to chromosome 22q13.1–13.2. Most ADSL deficiency patients are compound heterozygotes and in cases in which the parents have been genotyped, each parent carries one mutant and one normal allele and is asymptomatic. No individuals with ADSL deficiency are completely lacking in enzyme activity; complete lack of ADSL activity in humans is probably incompatible with life (Spiegel et al. 2006). The potential mechanisms whereby ADSL may provoke neurological manifestations include deficiency of purine nucleotides, impairment of energy metabolism, and toxic effects by accumulated intermediates (Ciardo et al. 2001).

The clinical presentation is characterized by severe neurologic involvement including seizures, developmental delay, hypotonia, and autistic features. Neonatal seizures and a severe infantile epileptic encephalopathy are often the first manifestations of this disorder. The epileptic phenotype consists of myoclonias, partial epilepsy, GTCS, spasms and status epilepticus (Ciardo et al. 2001).

Epilepsy in ADSL deficiency is usually associated with psychomotor delay, autism and signs of cerebellar and pyramidal dysfunction (Wolf et al. 2005).

Mitochondrial Diseases

Mitochondrial diseases (MCDs) are a clinically heterogeneous group of disorders that arise as a result of dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. They can be caused by mutations of nuclear or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) (Cree et al. 2009). Nuclear gene defects may be inherited in an autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant manner. Mitochondrial DNA defects are transmitted by maternal inheritance. Epilepsy is also a frequent CNS manifestation of MCDs. Seizure may start at infancy as infantile spasms, West syndrome, myoclonic jerks, astatic seizures, or juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy is particularly prevalent in patients with MELAS, MERRF, LS, or NARP (Finsterer 2006).

Several mitochondrial diseases have been linked to ineffective mtDNA replication by mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma (POLG). Mutations in POLG, are associated with Alpers syndrome (and Alpers-like encephalopathy), childhood Myocerebrohepatopathy spectrum disorders, ataxia-neuropathy syndromes, myoclonus epilepsy myopathy sensory ataxia, and dominant and recessive forms of progressive external ophthalmalplegia (PEO) (Milone and Massie 2010).

Mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome, also known as Alpers syndrome (OMIM #203700), is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a clinical triad of psychomotor retardation, intractable epilepsy, and liver failure. Seizures may initially be focal and subsequently generalize. Epilepsia partialis continua and convulsive status epilepticus are common. The disorder, diagnosed in infants and young children, is progressive and often leads to death from hepatic failure or status epilepticus before age 3 years. MtDNA in muscle and liver samples of Alpers syndrome patients is depleted (Milone and Massie 2010). The EEG features of posterior rhythmic high amplitude delta with superimposed polyspikes (RHADS) are very helpful although not mandatory in all cases. The course is usually rapidly progressive; most affected infants die before the age of 3 years (Wolf et al. 2009a, b).

Magnetic resonance imaging changes may be nonspecific, such as atrophy (both general and involving specific structures, such as cerebellum), more suggestive of particular disorders such as focal and often bilateral lesions confined to deep brain nuclei, or clearly characteristic of a given disorder such as stroke-like lesions that do not respect vascular boundaries in mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episode (MELAS). White matter hyperintensities with or without associated gray matter involvement may also be observed (Fig. 3; Friedman et al. 2010; Papetti et al. 2013).

Secondary mitochondrial dysfunction is also seen in a number of different genetic disorders, including ethylmalonic aciduria (EE, OMIM # 602473) (Tiranti et al. 2009). EE is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder of infancy affecting the brain, the gastrointestinal tract and peripheral vessels. It is caused by a defect in the ETHE1 gene product, which a mitochondrial dioxygenase involved in hydrogen sulfide (H (2) S) detoxification. Patients present in infancy with psychomotor retardation, chronic diarrhea, orthostatic acrocyanosis and relapsing petechiae. High levels of lactic acid, ethylmalonic acid (EMA) and methylsuccinic acid (MSA) are detected in body fluids. The signs and symptoms of EE are apparent at birth or begin in the first few months of life. Seizures start early as tonic seizure, spasms and West syndrome (Fig. 2; Papetti et al. 2013). MRI generally shows symmetrical increased signals on T2-weighted images in the basal ganglia which correspond to symmetrical necrotic lesions (Fig. 4). They occasionally have signal anomalies in subcortical areas, white matter, and brainstem (Pigeon et al. 2009).

Diagnostic approach in MCDs should include patient and family history, laboratory examination, and neurological workup as initial workups, then specific biochemical studies, muscle biopsy, and molecular genetic studies as the further workups. The most useful basic test is to check serum lactate level (Kang et al. 2013). In patients with mitochondrial encephalopathy, when pyruvate oxidation in mitochondria is disturbed due to abnormalities in pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, Krebs cycle, or electron transport chain, excessive pyruvate can be either transformed into alanine or reduced to lactate, increasing blood lactate level. The ratio of lactate to pyruvate depends on the degree of oxidation–reduction in tissue. Since the increase in serum lactate level can be equivocal in patients with mitochondrial encephalopathy, it is sometimes helpful to evaluate lactate level of cerebrospinal fluid. More specifically, a particularly significant increase in the ratio of lactate to pyruvate and 3-hydroxybutyrate to acetoacetate may suggest respiratory chain defect. The further diagnostic approaches to mitochondrial diseases include morphological observation using microscopic tools, biochemical assays that measure enzyme activities of respiratory chain reaction in skeletal muscles (most commonly complex I defect), and molecular genetic studies to examine mtDNA or nuclear DNA mutation (Kang et al. 2013).

To treat epilepsy with mitochondrial diseases, general supportive care is first provided to treat multiorgan involvement. Then, the children are given antioxidants and respiratory chain cofactors, along with recommendation for diet change to the ketogenic diet or caloric restriction. Finally, antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) are used to control seizure (Kang et al. 2013).

Coenzyme Q10 has been reported to have two functions, as an electron carrier in the mitochondrial respiratory chain reaction and as a scavenger molecule. It is important to identify and treat disorders of CoQ10 biosynthesis, since these remain the only readily treatable forms of mitochondrial epilepsy (Steele et al. 2004; Rahman et al. 2010, 2013). Many present in infancy with a multisystem syndrome including epilepsy, frequently associated with sensorineural hearing loss and a prominent steroid- resistant nephropathy. Other neurological features in these patients include nystagmus, ataxia, spasticity, and dystonia. Mutations in five genes (COQ2, PDSS1, PDSS2, COQ9, and COQ6) have so far been reported to cause infantile onset of CoQ10 deficiency. Treatment is with oral CoQ10 supple mentation; 10–30 mg/kg/day in three divided doses is usually sufficient. The best outcome in this disorder was reported in a female who was diagnosed early because of an affected older sibling, and in whom treatment was initiated at the first manifestation of disease (Montini et al. 2008; Rahman et al. 2010). Riboflavin, tocopherol (vitamin E), succinate, ascorbate (vitamin C), menadione, and nicotinamide have also been used to treat mitochondrial diseases with deficiency in specific enzymes (Kang et al. 2013).

Males with the X-linked form of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHc) deficiency usually present with Leigh syndrome (OMIM 308930), but females who are heterozygous for a severe mutation in the PDHA1 gene can present in the first 6 months of life with infantile spasms, an EEG showing hypsarrhythmia, and developmental regression (West syndrome), or just with severe myoclonic seizures (OMIM 312170). MRI may show periventricular multicystic leukoencephalopathy and agenesis of the corpus callosum. CSF lactate is often elevated, usually with an elevation of blood lactate, and fibroblast studies show reduced pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity. Some cases of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency respond well to treatment with thiamine and/or a ketogenic diet, and this reduction in seizure severity (Barnerias et al. 2010).

Childhood Onset Seizures

Storage Disorders

The neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses (NCLs) are a group of inherited, neurodegenerative, lysosomalstorage disorders characterized by progressive intellectual and motor deterioration, seizures, and early death . Visual loss is a feature of most forms. NCLs variants are classified by age of onset and order of appearance of the clinical features: infantile neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis (INCL), late-infantile (LINCL), juvenile (JNCL), adult (ANCL), and Northern epilepsy (NE, progressive epilepsy with intellectual disability) (Mole and Williams 2010). In INCL seizures start at the end of the first year of life, with myoclonus, atonic and GTCS followed by dementia and movement disorders. The EEG shows a depression of background activity (Pascual et al. 2008). Symptoms of LINCL generally appear after the second year of life. The seizures are GTCS, tonic clonic, atonic, myoclonic and myoclonic-astatic. The EEG can show epileptic discharges during intermittent photostimulation at 1 Hz (Wolf et al. 2009a, b). The JNCL form is characterized by seizures that typically appear between ages 5 and 18 years. Northern epilepsy is characterized by tonic-clonic or complexpartial seizures, intellectual disability, and motor dysfunction. Onset occurs between ages 2 and 10 years (Mole and Williams 2010) .

The genes PPT1 (CNL1), TPP1 (CNL2), CLN3, CLN5, CLN6, MFSD8 (CLN7), CLN8, and CTSD (CNL10) are known to be associated with NCLs. In INCL, a lysosomal enzyme, palmitoyl protein thioesterase 1 (PPT1) is deficient. Patients with LINCL are deficient in a pepstatin-insensitive lysosomal peptidasetripeptidyl peptidase 1 (TTP1). JNCL is due to mutation of CLN3 gene that encodes a protein that is thought to be a part of the lysosomal membrane. The ANCL is associated with mutations of the CLN4 gene (not mapped yet). Mutations in another gene, CLN5 is associated with Finnish variant LINCL that occurs predominantly in the Finnish population (Mole and Williams 2010).

Myoclonic epilepsy of Lafora (EPM2, OMIM #254780) is a severe autosomal recessive disorder characterized by fragmentary, symmetric, or generalized myoclonus and/or GTCS, occipital seizures, and progressive neurologic degeneration including cognitive and/or behavioral deterioration, dysarthria, and ataxia beginning in previously healthy adolescents between ages 12 and 17 years. The frequency and intractability of seizures increase over time. Survival is short, less than 10 years after onset. The disease is characterized by intracellular polyglucosan inclusions (Lafora bodies) in the brain, liver, skin and muscles (Monaghan and Delanty 2010) . Two genetic forms are known, one of which (EPM2A) is caused by mutations in the laforin gene and another (NHLRC1)–by mutations in the malin gene. The EMP2A encodes a protein phosphatase and NHLRC1 encodes an ubiquitin ligase. These two proteins interact with each other and, as a complex, are thought to regulate critical neuronal functions (Singh and Ganesh 2009).

Copper Metabolism Errors

Menkes disease (MD) is a multisystemic disorder of copper metabolism. Progressive neurodegeneration and connective tissue disturbances, together with the peculiar ‘kinky’ hair are the main manifestations. MD is inherited as an X-linked recessive trait, and is due to mutations in the ATP7A gene. The vast majority of ATP7A mutations are intragenic mutations or partial gene deletions. ATP7A is an energy dependent transmembrane protein, which is involved in the delivery of copper to the secreted copper enzymes and in the export of surplus copper from cells (Tümer and Møller 2010). Seizures may occur during the first few months of life, although there are mild forms of the defect with later onset and include myoclonus, spasms and multifocal seizures. Three successive periods in the course of epilepsy have been observed: early focal status, then infantile spasms, and then myoclonic and multifocal epilepsy after age 2 years (Bahi-Buisson et al. 2006).

Radiological findings are various and combine cortical and cerebellar atrophy, delayed myelinisation, tortuosity and dilatation of the intra- and extracranial vessels, and subdural fluid collections (Fig. 5) (Bahi-Buisson et al. 2006; Papetti et al. 2013).

Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (Cdg)

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are a group of disorders of abnormal glycosylation of Nlinked oligosaccharides caused by deficiency in 21 different enzymes in the N-linked oligosaccharide synthetic pathway. Most commonly, the disorders begin in infancy; manifestations range from severe developmental delay and hypotonia with multiple organ system involvement to hypoglycemia and protein-losing enteropathy with normal development (Sparks and Krasnewich 2011). Mutations identified in the 15 genes (PMM2, MPI, DPAGT1, ALG1, ALG2, ALG3, ALG9, ALG12, ALG6, ALG8, DOLK, DPM1, DPM3, MPDU1, and RFT1) yield a deficiency of dolichol-linked oligosaccharide biosynthesis resulting in CDG (Haeuptle and Hennet 2009). Epilepsy associated with developmental delay, dysmorphisms and hypotonia has been described more frequently in CDG-1d. Seizures generally start in the infancy and the EEG revealed generalized epileptic changes, while brain MRI shows evidence of leukodystrophy (Grünewald et al. 2000).

Lysosomal Storage Disorder

Gaucher disease (GD) is a lipid storage disease characterized by the recessively inherited deficiency of lysosomal glucocerebrosidase, encoded by GBA (OMIM# 606463). GD manifests with diverse symptoms, and is commonly divided into three types, based on the absence (type 1) and rate of progression of neurological manifestations (types 2 and 3) (Mignot et al. 2006). GD3 comprises a heterogeneous group of patients suffering either mild or severe systemic disease combined with variable neurological involvement. Two further subtypes of GD3 patients have been reported differentiating those with mild systemic involvement associated with progressive myoclonic epilepsy (PME), called GD3a, from those with severe systemic involvement associated with oculomotor apraxia (OMA), called GD3b (Kraoua et al. 2011). In a recent perspective study conducted by the International Collaborative Gaucher Group, seizures were reported in 19 out of 122 patients (16 %). Some patients had experienced more than one type of seizure. The types reported were tonic–clonic seizures (7 out of 122, 6 %), clonic seizures (5 out of 122, 4 %), tonic seizures (3 out of 120, 3 %), myoclonic seizures (3 out of 121, 2 %), typical absence seizures (2 out of 119, 2 %), and atypical absence seizures (1 out of 119, 1 %) (Tylki-Szymańska et al. 2010).

Niemann–Pick type C (NPC; OMIM 257220) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by accumulation of free cholesterol, sphingomyelin, glycosphingolipids (GSLs) and sphingosine in lysosomes, mainly due to a mutation in the NPC1 gene. The clinical spectrum of the disease ranges from a neonatal rapidly fatal disorder to an adult-onset chronic neurodegenerative disease. Epilepsy is generally a late onset manifestation with partial, generalized tonic–clonic and atonic seizures (Sévin et al. 2007).

Peroxisomal Disorders

X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (X-ALD, OMIM 300100) is an inherited, recessive, neurodegenerative disease affecting brain white matter, adrenal cortex and testis.

The disorder is caused by mutations in the ABCD1 gene, which impair peroxisomal b-oxidation, resulting in the accumulation of very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFa) in plasma. There are several distinct clinical phenotypes ranging from cerebral forms, adrenomyeloneuropathy (AMN) to asymptomatic persons or isolated adrenal insufficiency without CNS involvement (Addison’s disease only). Cerebral X-ALD is further divided into childhood (CCALD), adolescent (AdolCALD) and adult form (ADCALD). Affected boys with CCALD present before the age of 10 years a rapidly progressive disorder with ataxia, spasticity, deafness, visual deficits, personality changes and seizures. The less common adolescent form after the age of 10 years demonstrates similar course. Cerebral X-ALD is frequently associated with Addison’s disease, but the primary adrenal insufficiency may precede, coexist or develop after neurological disturbances. In one large series, 20 out of 485 individuals presented with seizures: focal seizures in six males and generalized in the remainder, with four having status epilepticus (Stephensons et al. 2000). Typical MR findings in the brain of X-ALD patients have been well documented recently and consist of bilateral white matter abnormalities. Typically they occur initially in the posterior cerebral regions and progress to parietal, temporal and frontal lobes sequentially. Such a pattern is found in approximately 80 % of cases; therefore MR strongly suggests the diagnosis of X-ALD (Poll-The 2012).

Conclusions

Inborn errors of metabolism are a rare cause of epilepsy in pediatric age. The suspicious of metabolic epilepsy should rise if seizures are refractory to standard antiepileptic drugs , and if additional symptoms are present such as mental retardation, dysmorphism, movement disorders, and visceral abnormalities. The recognition of metabolic causes of epilepsy requires a multidisciplinary approach and several investigations such as EEG, evoked potentials, neuroimaging (MRI-spectroscopy, SPECT), blood exams, urinary exams and CSF analysis. The diagnosis of metabolic disorders in epileptic patients may provide the possibility of specific treatments that can improve seizures.

References

Aicardi J (2007) Epilepsy syndromes. In: Engel J, Pedley TA, Aicardi J (eds) Epilepsy a comprehensive textbook, vol 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 2608–2609

Applegarth DA, Toone JR (2004) Glycine encephalopathy (nonketotic hyperglycinaemia): review and update. J Inherit Metab Dis 27:417–422

Bagci S, Zschocke J, Hoffmann GF, Bast T, Klepper J, Müller A et al (2008) Pyridoxal phosphate-dependent neonatal epileptic encephalopathy. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 93:151–152

Bahi-Buisson N, Kaminska A, Nabbout R, Barnerias C, Desguerre I, De Lonlay P et al (2006) Epilepsy in Menkes disease: analysis of clinical stages. Epilepsia 47:380–386

Balasubramaniam S, Bowling F, Carpenter K, Earl J, Chaitow J, Pitt J et al (2010) Perinatal hypophosphatasia presenting as neonatal epileptic encephalopathy with abnormal neurotransmitter metabolism secondary to reduced co-factor pyridoxal-5′-phosphate availability. J Inherit Metab Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10545-009-9012-y

Barnerias C, Saudubray JM, Touati G et al (2010) Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency: four neurological phenotypes with differing pathogenesis. Dev Med Child Neurol 52:1–9

Baxter P (2003) Pyridoxine-dependent seizures: a clinical and biochemical conundrum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1647:36–41

Baxter P (2010) Recent insights into pre- and postnatal pyridoxal phosphate deficiency, a treatable metabolic encephalopathy. Dev Med Child Neurol 52:597–598

Bhardwaj P, Kaushal RK, Chandel A (2010) Biotinidase deficiency: a treatable cause of infantile seizures. J Pediatr Neurosci 5:82–83

Blau N, van Spronsen FJ, Levy HL (2010) Phenylketonuria. Lancet 376:1417–1427

Braissant O (2010) Current concepts in the pathogenesis of urea cycle disorders. Mol Genet Metab 100:3–12

Brockmann K (2009) The expanding phenotype of GLUT1-deficiency syndrome. Brain Dev 31:545–552

Cerisola A, Campistol J, Pérez-Dueñas B, Poo P, Pineda M, García-Cazorla A et al (2009) Seizures versus dystonia in encephalopathic crisis of glutaric aciduria type I. Pediatr Neurol 40:426–431

Chemelli AP, Schocke M, Sperl W, Trieb T, Aichner F, Felber S (2000) Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in five patients with treated propionic acidemia. J Magn Reson Imaging 11:596–600

Ciardo F, Salerno C, Curatolo P (2001) Neurologic aspects of adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency. J Child Neurol 16:301–308

Clague A, Thomas A (2002) Neonatal biochemical screening for disease. Clin Chim Acta 315:99–110

Cree LM, Samuels DC, Chinnery PF (2009) The inheritance of pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations. Biochim Biophys Acta 1792:1097–1102

de Koning TJ, Klomp LW (2004) Serine-deficiency syndromes. Curr Opin Neurol 17:197–204

Dinopoulos A, Matsubara Y, Kure S (2005) Atypical variants of nonketotic hyperglycinemia. Mol Genet Metab 86:61–69

Finsterer J (2006) Central nervous system manifestations of mitochondrial disorders. Acta Neurol Scand 114:217–238

Friedman JR, Thiele EA, Wang D, Levine KB, Cloherty EK, Pfeifer HH et al (2006) Atypical GLUT1 deficiency with prominent movement disorder responsive to ketogenic diet. Mov Disord 21:241–245

Friedman SD, Shaw DWW, Ishak G, Gropman AL, Saneto RP (2010) The use of neuroimaging in the diagnosis of mitochondrial disease. Dev disabil Res rev 16:129–135

Gallagher RC, Van Hove JL, Scharer G, Hyland K, Plecko B, Waters PJ et al (2009) Folinic acid-responsive seizures are identical to pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy. Ann Neurol 65:550–556

Gospe SM Jr (2010) Neonatal vitamin-responsive epileptic encephalopathies. Chang Gung Med J 33:1–12

Gropman AL, Summar M, Leonard JV (2007) Neurological implications of urea cycle disorders. J Inherit Metab Dis 30:865–879

Grünewald S, Imbach T, Huijben K, Rubio-Gozalbo ME, Verrips A, de Klerk JB et al (2000) Clinical and biochemical characteristics of congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ic, the first recognized endoplasmic reticulum defect in N-glycan synthesis. Ann Neurol 47:776–781

Haberlandt E, Canestrini C, Brunner-Krainz M, Möslinger D, Mussner K, Plecko B et al (2009) Epilepsy in patients with propionic acidemia. Neuropediatrics 40:120–125

Haeuptle MA, Hennet T (2009) Congenital disorders of glycosylation: an update on defects affecting the biosynthesis of dolichol-linked oligosaccharides. Hum Mutat 30:1628–1641

Hamosh A, Scharer G, Van Hove J (2009) Glycine encephalopathy. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP (eds) GeneReviewse (Internet). University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1993–2002. (Bookshelf ID: NBK1357)

Hoffmann GF, Schmitt B, Windfuhr M, Wagner N, Strehl H, Bagci S et al (2007) Pyridoxal 50-phosphate may be curative in earlyonset epileptic encephalopathy. J Inherit Metab Dis 30:96–99

Jaeken J (2002) Genetic disorders of gamma-aminobutyric acid, glycine, and serine as causes of epilepsy. J Child Neurol 17:84–87

Joshi SN, Fathalla M, Koul R, Maney MA, Bayoumi R (2010) Biotin responsive seizures and encephalopathy due to biotinidase deficiency. Neurol India 58:323–324

Kang HC, Lee YM, Kim HD (2013) Mitochondrial disease and epilepsy. Brain Dev 35(8):757–761

Klepper J (2008) Glucose transporter deficiency syndrome (GLUT1DS) and the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 49:46–49

Klepper J, Leiendecker B (2007) GLUT1 deficiency syndrome-2007 update. Dev Med Child Neurol 49:707–716

Klepper J, Engelbrecht V, Scheffer H, van der Knaap MS, Fiedler A (2007) GLUT1 deficiency with delayed myelination responding to ketogenic diet. Pediatr Neurol 37:130–133

Korein J, Sansaricq C, Kalmijn M, Honig J, Lange B (1994) Murple syrup urine disease: clinical, EEG and plasma aminoacid correlations with a theoretical mechanism of acute neurotoxicity. Int J Neurosci 79:21–45

Kraoua I, Sedel F, Caillaud C, Froissart R, Stirnemann J, Chaurand G et al (2011) A French experience of type 3 Gaucher disease: phenotypic diversity and neurological outcome of 10 patients. Brain Dev 33(2):131–139

Kuo MF, Wang HS (2002) Pyridoxal phosphate-responsive epilepsy with resistance to pyridoxine. Pediatr Neurol 26:146–147

Leuzzi V (2002) Inborn errors of creatine metabolism and epilepsy: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Child Neurol 17(3):89–97

Leuzzi V1, Mastrangelo M, Battini R, Cioni G (2013) Inborn errors of creatine metabolism and epilepsy. Epilepsia 54(2):217–227

Martynyuk AE, Ucar DA, Yang DD, Norman WM, Carney PR, Dennis DM et al (2007) Epilepsy in phenylketonuria: a complex dependence on serum phenylalanine levels. Epilepsia 48:1143–1150

Matern D, Lehnert W, Gibson KM, Korinthenberg R (1996) Seizures in a boy with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency treated with vigabatrin (gamma-vinyl-GABA). J Inherit Metab Dis 19:313–318

McClelland VM, Bakalinova DB, Hendriksz C, Singh RP (2009) Glutaric aciduria type 1 presenting with epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 51:235–239

Mignot C, Doummar D, Maire I (2006) French type 2 Gaucher disease study group. Type 2 Gaucher disease: 15 new cases and review of the literature. Brain Dev 28(1):39–48

Mills PB, Surtees RAH, Champion MP, Beesley CE, Dalton N, Scambler PK et al (2005) Neonatal epileptic encephalopathy caused by mutations in the PNPO gene encoding pyridox (am)ine 5′-phosphate oxidase. Hum Mol Genet 14:1077–1086

Mills PB, Footitt EJ, Mills KA, Tuschl K, Aylett S, Varadkar S et al (2010) Genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy (ALDH7A1 deficiency). Brain 133:2148–2159

Milone M, Massie R (2010) Polymerase gamma 1 mutations: clinical correlations. Neurologist 16:84–91

Mole SE, Williams RE (2010) Neuronal Ceroid-Lipofuscinoses. In: Pagon RA, Bird TC, Dolan CR, Stephens K (eds) Gene reviews 2010. University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1993–2001

Monaghan TS, Delanty N (2010) Lafora disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. CNS Drugs 24:549–561

Montini G, Malaventura C, Salviati L (2008) Early coenzyme Q10 supplementation in primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency. N Engl J Med 358:2849–2850

Nabbout R, Dulac O (2008) Epileptic syndromes in infancy and childhood. Curr Opin Neurol 21:161–166

Nasrallah F, Feki M, Kaabachi N (2010) Creatine and creatine deficiency syndromes: biochemical and clinical aspects. Pediatr Neurol 42:163–171

Neumaier-Probst E, Harting I, Seitz A, Ding C, Kolker S (2004) Neuroradiological findings in glutaric aciduria type I (glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency). J Inherit Metab Dis 27:869–876

Overweg-Plandsoen WC, Groener JE, Wang D, Onkenhout W, Brouwer OF, Bakker HD et al (2003) GLUT-1 deficiency without epilepsy—an exceptional case. J Inherit Metab Dis 26:559–563

Papetti L, Parisi P, Leuzzi V, Nardecchia F, Nicita F, Ursitti F, Marra F, Paolino MC, Spalice A (2013) Metabolic epilepsy: an update. Brain Dev 35(9):827–841

Pascual JM, Campistol J, Gil-Nagel A (2008) Epilepsy in inherited metabolic disorders. Neurologist 14:2–14

Pearl PL (2009) New treatment paradigms in neonatal metabolic epilepsies. J Inherit Metab Dis 32:204–213

Pearl PL, Gibson KM (2004) Clinical aspects of the disorders of GABA metabolism in children. Curr Opin Neurol 17:107–113

Pearl PL, Taylor JL, Trzcinski S, Sokohl A (2007) The pediatric neurotransmitter disorders. J Child Neurol 22:606–616

Pearl PL, Vezina LG, Saneto RP, McCarter R, Molloy-Wells E, Heffron A et al (2009) Cerebral MRI abnormalities associated with vigabatrin therapy. Epilepsia 50:184–94

Pigeon N, Campeau PM, Cyr D, Lemieux B, Clarke JT (2009) Clinical heterogeneity in ethylmalonic encephalopathy. J Child Neurol 24:991–296

Pindolia K, Jordan M, Wolf B (2010) Analysis of mutations causing biotinidase deficiency. Hum Mutat 31:983–991

Plecko B, Stöckler S (2009) Vitamin B6 dependent seizures. Can J Neurol Sci 36:73–77

Rahman S, Clarke CF, Hirano M (2012) 176th ENMC International Workshop: diagnosis and treatment of coenzyme Q10 deficiency. Neuromuscul Disord 22:76–86

Rahman S, Footitt EJ, Varadkar S, Clayton PT (2013) Inborn errors of metabolism causing epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 55(1):23–36

Rossi S, Daniele I, Bastrenta P, Mastrangelo M, Lista G (2009) Early myoclonic encephalopathy and nonketotic hyperglycinemia. Pediatr Neurol 241:371–374

Rotstein M, Engelstad K, Yang H, Wang D, Levy B et al (2010) Glut1 deficiency: inheritance pattern determined by haploinsufficiency. Ann Neurol 68:955–8

Scharer G, Brocker C, Vasiliou V, Creadon-Swindell G, Gallagher RC, Spector E et al (2010) The genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of pyridoxine-dependent epilepsy due to mutations in ALDH7A1. J Inherit Metab Dis 33:571–581

Schneider SA, Paisan-Ruiz C, Garcia-Gorostiaga I, Quinn NP, Weber YG, Lerche H et al (2009) GLUT1 gene mutations cause sporadic paroxysmal exercise-induced dyskinesias. Mov Disord 24:1684–8

Sévin M, Lesca G, Baumann N, Millat G, Lyon-Caen O, Vanier MT et al (2007) The adult form of Niemann–Pick disease type C. Brain 130(Pt 1):120–133

Seashore MR (2009) The organic acidemias: an overview. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP (eds) GeneReviewse (Internet). University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1993–2001. (Bookshelf ID: NBK1134)

Seidner G, Alvarez MG, Yeh JI, O’Driscoll KR, Klepper J, Stump TS et al (1998) GLUT-1 deficiency syndrome caused by haploinsufficiency of the blood–brain barrier hexose carrier. Nat Genet 18:188–191

Singh S, Ganesh S (2009) Lafora progressive myoclonus epilepsy: a meta-analysis of reported mutations in the first decade following the discovery of the EPM2A and NHLRC1 genes. Hum Mutat 30:715–723

Sparks SE, Krasnewich DM (2011) Congenital disorders of glycosylation overview. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP (eds) GeneReviewse (Internet). University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1993–2005. (Bookshelf ID: NBK1332)

Spiegel EK, Colman RF, Patterson D (2006) Adenylosuccinate lyase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 89:19–31

Steele PE, Tang PH, DeGrauw AJ, Miles MV (2004) Clinical laboratory monitoring of coenzyme Q10 use in neurologic and muscular diseases. Am J Clin Pathol 121:113–120

Steinberg SJ, Raymond GV, Braverman NE, Moser AB (2003) Peroxisome biogenesis disorders, zellweger syndrome spectrum. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP (eds) GeneReviewse (Internet). University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1993–2003. (Bookshelf ID:1448)

Stephenson DJ, Bezman L, Raymond GV (2000) Acute presentation of childhood adrenoleukodystrophy. Neuropediatrics 31:293–297

Suls A, Dedeken P, Goffin K, Van Esch H, Dupont P, Cassiman D et al (2008) Paroxysmal exercise-induced dyskinesia and epilepsy is due to mutations in SLC2A1, encoding the glucose transporter GLUT1. Brain 131:1831–1844

Summar ML (2005). Urea cycle disorders overview. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Stephens K, Adam MP (eds) GeneReviewse (Internet). University of Washington, Seattle, pp 1993–2002. (Bookshelf ID: NBK1217)

Suzuki Y, Yang X, Aoki Y, Kure S, Matsubara Y (2005) Mutations in the holocarboxylase synthetase gene HLCS. Hum Mutat 26:285–290

Tabatabaie L, Klomp LW, Berger R, de Koning TJ (2010) L-serine synthesis in the central nervous system: a review on serine deficiency disorders. Mol Genet Metab 99:256–262

Takahashi Y, Suzuki Y, Kumazaki K, Tanabe Y, Akaboshi S, Miura K et al (1997) Epilepsy in peroxisomal diseases. Epilepsia 38(2):182–8

Thoene J, Wolf B (1983) Biotinidase deficiency in juvenile multiple carboxylase deficiency. Lancet 2:398

Tiranti V, Viscomi C, Hildebrandt T, Di Meo I, Mineri R, Tiveron C et al (2009) Loss of ETHE1, a mitochondrial dioxygenase, causes fatal sulfide toxicity in ethylmalonic encephalopathy. Nat Med 15:200–205

Tümer Z, Møller LB (2010) Menkes disease. Eur J Hum Genet 18:511–518

Tylki-Szymańska A, Vellodi A, El-Beshlawy A, Cole JA, Kolodny E (2010) Neuronopathic Gaucher disease: demographic and clinical features of 131 patients enrolled in the International Collaborative Gaucher Group Neurological Outcomes Subregistry. J Inherit Metab Dis 33(4):339–346

Van Gosen L (2008) Organic acidemias: a methylmalonic and propionic focus. J Pediatr Nurs 23:225–233

Vannucci SJ, Maher F, Simpson IA (1997) Glucose transporter proteins in brain: delivery of glucose to neurons and glia. Glia 21:2–21

Verhoeven NM, Salomons GS, Jakobs C (2005) Laboratory diagnosis of defects of creatine biosynthesis and transport. Clin Chim Acta 361:1–9