Abstract

The Ecological Society of America (ESA) has responded to the growing commitment among ecologists to make their science relevant to society through a series of concerted efforts, including the Sustainable Biosphere Initiative (1991), scientific assessment of ecosystem management (1996), ESA’s vision for the future (2003), Rapid Response Teams that respond to environmental crises (2005), and the Earth Stewardship Initiative (2009). During the past 25 years, ESA launched five new journals, largely reflecting the expansion of scholarship linking ecology with broader societal issues. The goal of the Earth Stewardship Initiative is to raise awareness and to explore ways for ecologists and other scientists to contribute more effectively to the sustainability of our planet. This has occurred through four approaches: (1) articulation of the stewardship concept in ESA publications and Website, (2) selection of meeting themes and symposia, (3) engagement of ESA sections in implementing the initiative, and (4) outreach beyond ecology through collaborations and demonstration projects. Collaborations include societies and groups of Earth and social scientists, practitioners and policy makers, religious and business leaders, federal agencies, and artists and writers. The Earth Stewardship Initiative is a work in progress, so next steps likely include continued nurturing of these emerging collaborations, advancing the development of sustainability and stewardship theory, improving communication of stewardship science, and identifying opportunities for scientists and civil society to take actions that move the Earth toward a more sustainable trajectory.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Earth Stewardship Initiative

- Ecological Society of America

- Interdisciplinary integration

- Practitioner Engagement

- Sustainability

1 Introduction

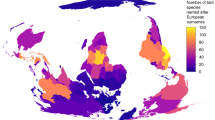

Societies around the world are anxious to meet the needs of their growing human populations and to satisfy their rising aspirations. Human desires for high quality of life, material comfort, and consumption-based lifestyles are now shared around the world. Response to these pressures relies on industrial processes and global trade, which together are greatly expanding the human capacity to disrupt the biosphere. Growth in these human capacities has led to the global decline in biodiversity and other benefits that society receives from ecosystems (MEA 2005). These impacts have accelerated over the last 60 years (Steffen et al. 2004) and may now be approaching or exceeding the limits of ecologically tolerable environmental change (Ellis and Ramankutty 2008; Foley et al. 2005; Rockström et al. 2009).

Although the serious degradation of the Earth System is widely recognized by the scientific community, governments are frequently reluctant to adopt policies that would radically reduce the rates of change and degradation, for fear of economic repercussions. Aggressive actions that are taken now, however, are likely to be much less costly than the price of failing to act promptly (NRC 2010; Stern 2007). However, it is not only governments that seem constrained from acting. Individuals may not see the relevance of the status of the Earth’s ecological processes to their lives and may therefore be tone deaf to their own responsibilities for the health of the Earth System (Hargrove 2015 in this volume [Chap. 20]).

Given the pace of environmental deterioration and the increased recognition that this path is unsustainable, society in all its aspects must seize the opportunity to reorient its relationship to the biosphere (DeFries et al. 2012) and ask what do humans owe to nature and to future generations? The scientific community has worked to develop the science needed for a more sustainable relationship between society and the planet (Lubchenco et al. 1991; MEA 2005) and to assess the rates, causes, and consequences of human pressure on the environment (IPCC 2014; Melillo et al. 2014). Civil society, including individual citizens, businesses, religious and non-governmental organizations, communities, and tribes, have sought to apply this understanding to reduce society’s impacts on the environment, but these efforts have so far been insufficient to stem the tide of degradation of Earth’s life-support system. A broader, ethically framed approach is needed to move forward. We believe the concept of stewardship provides a compelling framework to move beyond what science can accomplish on its own.

In 2009, the Ecological Society of America (ESA) launched an initiative in Earth Stewardship to raise awareness and to explore ways that ecologists and other scientists could increase their effectiveness in shifting the planet toward a more sustainable trajectory. This parallels the Planetary Stewardship Initiative developed internationally as part of scientific planning for Future Earth (Steffen et al. 2011). We define Earth Stewardship as a strategy to shape the trajectories of change in coupled social-ecological systems to foster ecosystem resilience and human well-being. It builds on sustainability science (Clark and Dickson 2003; Kates et al. 2001; Matson 2009; Turner et al. 2003) and explores approaches to apply this science to urgent problems facing society and the biosphere (Chapin and Fernandez 2013).

Stewardship, according to the Merriam Webster dictionary, means “the activity and job of protecting and being responsible for something” (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stewardship). The word is an old one, dating from the fifteenth century. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary (etymonline.com), it combines the idea of a house or hall (stig), such as on an estate or large farm, with the concept of a guard (weard). Thus, a steward is one who is entrusted with the care of a household. Responsibility in a deep and participatory sense is suggested by stewardship. However, it also implies that the task is undertaken on behalf of someone else or a larger entity (May Jr (2015) in this volume [Chap. 7]). In English and Scottish use, it can also apply to the care of a large political jurisdiction. The term has more recently come to mean provisioning of ships, and by extension, events, trains, or airplanes.

The original meaning, focusing on households, seems quite appropriate for an environmental application. A household associated with an area of land would include related and unrelated persons and would keep and maintain animals, woodlots, and gardens. The sense of responsibility and careful guardianship would attend the stewardship of a household. Consider that the terms “ecology” and “economics” also come from a formulation based on Greek that includes the idea of the household – of nature in this case. Ecology is the study of the household of nature, and economics relates to its management. Stewardship of Earth acknowledges that humans are members of the household of nature and that they bear responsibility to care attentively for this household.

The concept of Earth Stewardship, although rooted in religious thought (Conradie 2006; Hargrove 2015 in this volume [Chap. 20]; Kearns and Keller 2007), is a broadly ethical idea that does not rely on any one religious tradition in its call for responsibility to and membership in the larger Earth system and community. Indeed, its inclusiveness is suggested by similarity to principles underlying efforts as different as U.S. environmental policy, strategies for sustainability in developing nations (UN 2010; WCED 1987), and adaptive ecosystem management (Chapin et al. 2009; Christensen et al. 1996; Szaro et al. 1999). The concept of stewardship is familiar to the general public and has essentially the same meaning in lay terms as we intend in its scientific usage. Its goals are thus widely accepted by scientists, policy makers, and civil society, although their application inevitably raises contentious issues regarding tradeoffs (Clark and Levin 2010). The familiarity of the term stewardship facilitates communication with the larger civil society, although its diverse connotations can be problematic in some quarters (Hargrove 2015 in this volume [Chap. 20]), just as with “sustainability”.

2 Evolution of ESA’s Stewardship Approach

Since ESA’s founding in 1915, the society has sought to provide leadership in both cutting-edge science and its application to environmental issues. Early leaders such as Victor Shelford and William Cooper played important roles in establishing National Parks and other areas for conservation. Eugene Odum advocated passionately throughout his career for the protection of Earth’s endangered life-support systems (Odum 1989). However, tension between “basic” and “applied” research caused a group of ecologists to split away from ESA and form The Nature Conservancy in 1951 to pursue issues of explicit societal relevance, leaving ESA as the home for “basic” scientific ecology (Callicott (2015) in this volume [Chap. 11]).

Beginning in the late 1980s, ESA developed a research agenda for ecology. Under the leadership of five successive ESA presidents (1988–1992), the society came together to establish the Sustainable Biosphere Initiative (SBI), whose goal was to “define the role of ecological science in the wise management of Earth’s resources and the management of Earth’s life support system” (Lubchenco 2012; Lubchenco et al. 1991). The SBI identified three research priorities requiring particular attention in addressing global environmental problems: global change, biodiversity loss, and sustainable ecological systems. An important contribution of the SBI was the recognition of tight coupling between human activities and ecological processes on an increasingly human-dominated planet, with an emphasis on the application of ecological science to address these issues.

There were several important outcomes of the SBI. Membership in ESA broadly embraced the SBI’s commitment to research that bridged basic and applied ecological science to contribute to the wise management of Earth’s resources. As part of this commitment, ESA established an SBI office 1992 in Washington, D.C. to facilitate access to national government and relevant agencies and to inform government more effectively about the ecological repercussions of its policies. ESA established a policy office in 1983, which developed an education program in 1998 that subsequently branched off as an independent education office in 2003. The SBI office became the ESA science office in 1997. Together these offices foster the development of societally relevant ecological science and its application to policy and education. An ad-hoc committee was formed by ESA to assess the scientific underpinnings of ecosystem management, which took a holistic approach toward managing ecosystems and strongly emphasized sustainability (Christensen et al. 1996). In 2003, some 15 years after the SBI was launched, the ESA Ecological Visions Committee engaged in a second visioning exercise to assess the fit of ESA’s activities to its goals and mission (Palmer et al. 2004; Palmer et al. 2005). Key points derived from this exercise were the need to acknowledge the extent of the human footprint globally and to use ecological knowledge as a solution-based science to improve ecosystem services and human well-being.

This more recent visioning process led to two significant outcomes. One recommendation was for the establishment in 2005 of Rapid Response Teams, a group of ecologists who are knowledgeable about ecological issues of societal relevance and are committed to respond rapidly when this knowledge is needed to inform government actions or issue media statements. This team of about 50 experts serves as panelists in briefings for congressional staff, provides expert testimony to Congress, analyzes the likely ecological consequences of proposed changes to environmental regulations, and provides scientific feedback for news stories. A second recommendation from the Visioning Committee was the establishment of a center that would link ecologists, other researchers, managers and policy makers for communicating and implementing ecological science for solutions. The National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC; http://www.sesync.org/), funded by the National Science Foundation, directly addresses this recommendation. Projects at SESYNC focus on actionable science that can inform decisions within government, business, and households to improve the implementation of public policies and inform environmental planning.

ESA’s commitment to stewardship is also reflected in the history of its journals. In 1991 it undertook publication of a new journal, Ecological Applications, which is concerned broadly with the applications of ecological science to environmental problems. It publishes papers that develop scientific principles to support environmental decision-making, as well as papers that discuss the application of ecological concepts to environmental issues, policy, and management. Ecological Applications is intended to be accessible to both scholars and practitioners. More recent ESA journals show an increasing commitment to societal issues: Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment (started in 2003), Ecosphere (started in 2010), and Ecosystem Health and Sustainability published jointly with the Ecological Society of China (started in 2015). All demonstrate this commitment. The series Issues in Ecology (started in 1997) report the consensus of scientific experts on specific issues related to the environment, using commonly understood language. Its intended audience includes decision-makers at all levels for whom an objective presentation of the underlying science will increase the likelihood of ecologically-informed decisions. Many of the numbers of the series Issues in Ecology are available not only in English, but also in Spanish.

Parallel to ESA’s efforts, the National Academy of Sciences brought together scholars from a variety of natural and social sciences to advance societally relevant “sustainability science” (Clark and Dickson 2003; Kates et al. 2001; Matson 2009; NRC 1999), whose goal is to “promote human well-being while conserving the life support systems of the planet” (Clark and Levin 2010). In 2004, ESA initiated a Sustainability Science Award to recognize authors who have made the greatest contribution to sustainability science through the integration of ecological and social sciences.

ESA’s Earth Stewardship Initiative developed over several years reflecting the commitment of several ESA presidents and a broad spectrum of ESA members (Chapin et al. 2011; Power and Chapin 2009). Most significantly, the Earth Stewardship Initiative coincided with increased engagement and commitment to action by ESA’s student section, one of the society’s largest sections, clearly indicating the desire of the next generation of ecologists to address important environmental challenges. The Earth Stewardship Initiative builds upon the research agendas of the SBI and sustainability science with an emphasis on applying this understanding to help shape a more sustainable pathway for Earth as a social-ecological system. There are numerous ways to shape pathways of change toward a more sustainable future, including building the science as advocated by SBI and the Ecological Visions Committee, engaging the public and practitioners, communicating more effectively with the public and with policy makers, and conducting research that explicitly includes efforts to shape a more sustainable future. Box 12.1 illustrates some of these approaches, and the following sections describe ESA’s efforts to engage ecologists and a broader range of scientists and practitioners in meeting the needs for a more sustainable future of our planet.

Box 12.1: Examples of Stewardship Applications

SEEDS Campus BioBlitz Campaign

BioBlitz is a community engagement exercise developed by ESA’s Applied Ecology Section to acquaint local residents with the biodiversity in their neighborhoods. It is a quick comprehensive inventory of local biodiversity that typically requires both professional scientists with ecological and taxonomic expertise and resident volunteers to search for and collect local species of flora and fauna. It has been an effective approach to engagement and communication between ESA members and underserved communities in cities where ESA holds its annual meetings (Fig. 12.1). ESA’s Strategies for Ecology Education, Diversity and Sustainability (SEEDS) Program expanded the use of BioBlitzes by organizing BioBlitzes in communities associated with local campus chapters, using an informational document they developed. SEEDS students find that a BioBlitz helps raise community awareness of the diversity of living organisms in their neighborhood and the ecosystem services they provide. Goals of the BioBlitz program include promoting environmental programs on campuses and their surrounding communities, engaging volunteers in citizen science, providing a vehicle for both informal and formal environmental education, creation of databases of local species, and stimulating political awareness about biodiversity and environmental degradation.

ESA Graduate Student Response to the BP Oil Spill of 2010

In response to the British Petroleum (BP) oil rig explosion and fire of April 2010, Student Section chair Rob Salguero-Gomez and chair-elect Jorge Ramos harnessed the enthusiasm, energy, networking skills, and commitment to the environment of ESA’s student membership. They assembled metadata from the work of ecologists, both ESA members and others, documenting pre-spill conditions in estuaries, shorelines, and marine environments in the affected states along the Gulf Coast. Mark Stromberg of the University of California Natural Reserve System shared database software developed by the Organization for Biological Field Stations, which was subsequently tweaked by ESA web-developers. Student section leaders and ESA SEEDS students assembled an ESA database on research and researchers with relevant pre-spill information and shared this with research institutions, agencies, and local universities working on spill assessment and recovery. Through listservs and social networks, ecologists and other scientists learned about the effort and emailed datasets and photographs to the ESA’s Student Section. Jorge and Rob collated the information, made it available via ESA’s website to resource managers in the affected Gulf Coast states. ESA Student Section leaders and Public Affairs staff also distributed a compilation of state-specific links for opportunities to volunteer with clean-up and rescue of oiled wildlife (http://www.esa.org/esablog/research/conservation/taking-action-what-is-being-done-and-what-you-can-do-for-the-gulf/) (Ramos et al. 2012).

Ranching, Local Ecological Knowledge, and the Stewardship of Public Lands

After decades of controversy over grazing and fire, ranching families, conservation groups, agency officials, and engaged citizens are finding ways to link sustainable grazing with conservation in prairie grasslands of the Southwestern US. Sustainable grazing can preserve open space and wildlife habitat, allow oversight of exploding recreation, and motivate restoration of degraded lands and watersheds (Sayre 2005; Silbert et al. 2007). These outcomes, however, depend critically on the knowledge of local ecosystems held by multi-generational ranching families, particularly during this era of rapid environmental change. Two efforts in the Grand Canyon region have enhanced stewardship of the social-ecological systems on ranches and our public lands. In the early 1990s, two ranching families joined with former critics in the environmental community to form the Diablo Trust, a collaborative management group sponsoring monitoring research that informs ranch practices, conservation projects, and policy reform (Muñoz-Erickson et al. 2009; Sisk 2010). On the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, another collaborative effort came together when the Grand Canyon Trust, a leading conservation organization, purchased the historic Kane and Two-mile Ranches to reform the livestock business from within, linking ranching with overarching commitments to ecosystem restoration and biodiversity conservation across 380,000 ha of public land (Sisk et al. 2010). These collaborations moved controversy out of the courtroom and into the use of evidenced-based science to improve stewardship of public lands and resources.

Salmon, Cyanobacteria, and Watershed Stewardship in Northwestern California

In 2011, people living along the Eel River in northwestern California, concerned about diminishing flows, recovery of salmonids, and a rash of toxic algal blooms, formed the Eel River Recovery Project (ERRP) (Fig. 12.2). Like many rivers of the western US, the Eel historically supported iconic Pacific salmon populations (Yoshiyama and Moyle 2010). Juvenile salmonids thrive when their invertebrate prey are fueled by edible algae (particularly diatoms). These diatoms and their macro-algal hosts, which act as substrates that vastly increase diatom surface area, can colonize in rivers and dominate when summer flows connect and flush channel habitats. However, when drought and/or human water extraction decrease the flows of river waters, these edible algal assemblages can become overgrown by cyanobacteria, some of which are toxic. Summer water extraction has recently been greatly exacerbated by burgeoning marijuana cultivation. ERRP volunteers, tribal members from the Eel and Klamath basins, and researchers (ecologists and phycologists) at the Angelo Coast Range Reserve have teamed together to: (1) share algal identification skills, so local residents can distinguish the “good, the bad, and the structural” algae (Fig. 12.3), and (2) partner in basin-scale surveillance to track changes in salmonids, algae and channel environments under climatic and human-induced drought. The Eel River Critical Zone Observatory (http://criticalzone.org/eel/), which hosts scientists studying the effects on stream flow of geology, topography, vegetation cover, human activities and climate in these steep forested basins, promotes exchange among scientists, ERRP volunteers (http://www.eelriverrecovery.org/algal_foray), and other citizens and tribal members concerned about rivers along the California North Coast. The collaboration of researchers and citizen scientists and tribal members in watching, analyzing, interpreting, and forecasting flow-driven changes in river ecosystems will guide practices that could enhance resilience under drought for this vulnerable but important coastal landscape (Power et al. 2015).

3 Engaging Ecologists in Stewardship

Both the SBI and the Earth Stewardship Initiative were initially proposed to ESA members with some trepidation, given ESA’s history of reluctance to address the link between science and policy, which may have reflected a fear that this could lead to advocacy, such that the credibility or objectivity of the science would be jeopardized (Lubchenco 2012; Callicott (2015) in this volume [Chap. 11]). However, both initiatives came to be widely supported by ESA membership, particularly by younger members. Both initiatives represent an expansion of ESA’s goals from a focus on communication of ecological science among members to “raising public awareness and ensuring the appropriate use of ecological science in environmental decision making” (http://www.esa.org/esa/). ESA has explored and promoted the Earth Stewardship Initiative among ecologists largely through four approaches:

-

1.

articulation of the Earth Stewardship Initiative concept in ESA publications (Chapin et al. 2011; Power and Chapin 2009; Sayre et al. 2013) and Website (http://www.esa.org/esa/?page_id=2157),

-

2.

selection of meeting themes and symposia (Box 12.2),

-

3.

engagement of ESA sections to implement the initiative more broadly, and

-

4.

outreach beyond ecology through collaborations and demonstration projects.

Box 12.2: ESA Meeting Themes (in Bold) and Examples of Stewardship-Related Symposia Since Launching of the Earth Stewardship Initiative

2010: Global warming: The legacy of our past, the challenge for our future

-

Environmental scientists as effective advocates: Above the din but in the fray

-

Planetary stewardship and the MAHB

-

Climate and justice: Exploring equity through land, water, and culture

-

Global warming, smallholder agriculture, and environmental justice: Making critical connections

-

Contributions of citizen science to our understanding of ecological responses to climate change

2011: Earth Stewardship: Preserving and enhancing Earth’s life-support systems

-

Earth stewardship: Defining the scientific challenges and opportunities

-

Building a global sense of place, responsibility and stewardship

-

How we manage our share of Planet Earth

-

Thirty years of Earth Stewardship research: Long-term matters

-

Stewardship of urban systems: Socio-ecology, governance, and equity in the ULTRA network

-

Micro-managing the planet: Integrating microbial ecology and Earth Stewardship

-

A natural history initiative for ecology, stewardship, and sustainability

-

Revolutionary ecology: Defining and conducting stewardship and action as ecologists and global citizens

-

Integrating evolution into policy: Improved science-based decision-making for environmental stewardship

-

Warfare ecology: Impacts of conflict on environmental security and stewardship

-

Global perspectives of Earth Stewardship

2012: Life on Earth: Preserving, utilizing, and sustaining our ecosystems

-

Interacting with practitioners to facilitate Earth Stewardship

-

Human behavior and sustainability: Addressing barriers to change

-

Revolutionary ecology: The role of diversity in unleashing ecology’s potential to improve environmental conditions and societal welfare

-

Translational ecology: Forging effective links between knowledge and action

-

The new grand challenge for ecology: Sustaining agriculture while promoting environmental justice

-

Ecological consequences of multiple changes in Asia and their implications to global sustainability

-

Grappling with intangibles: Bringing cultural ecosystem services into decision-making

-

The evolving role of environmental scientists in informing ecosystem policy and management

-

Conservation in a globalizing world

-

Commodifying nature: The scientific basis for ecosystem service valuation in environmental decision making

2013: Sustainable pathways: Learning from the past and shaping the future

-

Resilience, disturbance and long-term environmental change: Integrating paleoecology into conservation and management in the Anthropocene

-

Can ethics and justice pave a sustainable pathway for human ecosystems

-

Ecology across borders: International, national, and cultural challenges of managing species internationally

-

Ecological sustainability in a telecoupled world

-

Past, present and future design of infrastructures for a resilient society

-

The ecology-policy interface: Perspectives on student engagement

2014: From oceans to Mountains: It’s all ecology

-

Ecosystem stewardship through traditional resource and environmental management: Indigenous management models from around the globe

-

Use-inspired ecological research that moves knowledge to action

-

The view from the trenches: Perspectives and advice from scientists engaged in science, policy and advocacy

-

What can ecologists learn from communities: A dialogue on Earth Stewardship from the dual perspectives of communities engaged in ecology and ecologists engaged in communities

-

Ecological design and planning for ecologists: Applying Earth Stewardship

-

Engaging with business and industry to advance Earth Stewardship: Business and biodiversity

-

Sustainable sourcing of food products: Social-ecological perspectives of constraints and opportunities for sustainable food production strategies

-

Green cities: Ecology and design in urban landscapes

-

Understanding and managing ecological resilience to natural disasters in a changing environment

-

Mitigating impacts to ecosystem services: Approaches, assumptions, and advances

-

From studying to shaping: A design charette bridging site analysis to conceptual design

-

Analysis of the ecological dimensions in general public energy education programs of major justice, faith-based, indigenous, and environmental organizations: Energizing a future role for ecologists

-

Promoting urban sustainability via linkages among stewardship, urban yards, biodiversity, and ecosystem services

The student section of ESA has been most active and innovative in exploring ways to incorporate Earth Stewardship into their section activities. Five ESA student members summarized some of the ways that graduate students and their university departments could individually and collectively be more effectively engaged in Earth Stewardship (Colón-Rivera et al. 2013). In addition, the student section has been a reasoned and effective advocate for “action ecology,” an expansion of ecological science into the realm of research that directly supports decision-making and policy (Bonilla et al. 2012; Rivera et al. 2010). They have done this, for example, by sponsoring symposia on this topic (sometimes under the label of “Revolutionary Ecology”; Marshall et al. 2011) at several recent ESA annual meetings. They were instrumental in organizing an initiative to assess ecosystem services in response to the British Petroleum oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico (Ramos et al. 2012) and have participated actively since 2008 in BioBlitzes that engage residents in documenting local biodiversity (Box 12.1). ESA graduate students have been consistent, active participants in congressional staff visits in Washington. For example, in April 2014, five graduate students visited congressional offices to explain the value of ecological science to the nation and to press for continued support for scientific research (http://www.esa.org/newsletter/eiaSpring14.html).

The extent of engagement of other ESA sections in the Earth Stewardship Initiative has been variable. In general, the sections that focus explicitly on human-nature interactions have been consistently active and account for much of the current implementation of Earth Stewardship within ESA. For example, the Human Ecology Section has regularly organized symposia at annual meetings and has served as the interface between ESA and its international counterpart—the Society for Human Ecology. The Environmental Justice Section has also organized symposia and played an active outreach role by engaging environmental groups associated with various communities of faith and by organizing a speakers bureau, as described in the next section. The Traditional Knowledge Section has regularly met with local tribes in the region of each ESA annual meeting to increase the awareness of ESA members of the indigenous heritage of the US, and on occasions also with indigenous people from other countries, to foster engagement of indigenous peoples in local and global ecological and environmental issues. About half of the ESA Sections (including Agroecology, Applied Ecology, Aquatic Ecology, Asian Ecology, Education, Environmental Justice, Long-term Studies, Microbial Ecology, Natural History, Paleoecology, Policy, Rangeland Ecology, and Urban Ecosystem Ecology) have also organized symposia at annual meetings that explore the societal relevance of their subdisciplines in an Earth Stewardship context.

Since the launching of the Earth Stewardship Initiative, there has been a gradual increase in the number of ESA sections actively involved in the initiative. During the past 5 years, topics of symposia, which are generally co-sponsored by multiple ESA sections, have gradually evolved from conceptualization to implementation to evaluation of Earth Stewardship approaches (Box 12.2). In general, the involvement of ESA sections has broadened the leadership and intellectual framework of the Earth Stewardship Initiative and has led to more diverse pathways for engagement of ESA members in its implementation.

The 2014 meeting included a demonstration project for the application of ecosystem stewardship and other aspects of ecology: “Cities that work for people and ecosystems.” Using the American River Parkway that runs through downtown Sacramento CA, the project demonstrates how ecological research, working at the intersection between ecological science and urban design, can monitor and adjust management practices using ecological principles, in order to work toward sustainability goals.

ESA’s Public Affairs office sponsors or co-sponsors congressional briefings on topics relevant to the Earth Stewardship Initiative, taking advantage of its Washington, D.C.-based policy office and the expertise represented by its members. Recent briefings have included topics such as water resources, climate-change impacts and adaptation, and improvement of flood management. Field trips and exhibits targeting policy makers are another way that ESA tries to broaden its impact. The ESA Office of Science Programs focuses its activities on advancing ecological science, but also on projects that link ecological research and management communities to more effectively integrate ecological science into decision-making and education. Its third category of activities focuses on solutions for sustainability, through a series of activities that examine and articulate the intellectual foundations for a new sustainability science. Since 2008 the Education and Diversity Programs Office has coordinated workshops, webinars, and speaking tours to promote the future of continental-scale science and education primarily to undergraduate institutions and underrepresented audiences in ecology. Its project on the Future of Environmental Decisions also included graduate students.

4 Moving Beyond Ecology

Recognizing that Earth Stewardship must be much broader than ecology, ESA began a series of efforts to collaborate with other disciplines and practices. This began with a symposium on scientific foundations of Earth Stewardship organized jointly with physical scientists at the 2010 annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU). This symposium highlighted readily implementable opportunities for biophysical collaborations to address Earth Stewardship. One such initiative, led by AGU in collaboration with several academic societies, explores the challenge of communicating climate change (AGU 2013). ESA organized a series of informal meetings with leaders of (1) various social-science societies, (2) various societies representing practitioners (e.g., planners and engineers), (3) various federal agencies, and (4) various religious groups in the hopes that ESA might collaborate with these groups to develop jointly the concept of Earth Stewardship or a suite of compatible concepts that would engage a range of disciplines and practices in shifting the planet toward a more sustainable trajectory.

These conversations led to a workshop of natural and social scientists, practitioners, and religious scholars in 2012. The workshop brought together representatives from academia, federal agencies, religious organizations, business, and planning/design organizations to discuss building strategic interdisciplinary partnerships to foster sustainability. During the workshop participants identified challenges to implementing Earth Stewardship, along with possible solutions and novel ways to collaborate across sectors and disciplines. The special issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment resulting from the workshop (2013, Vol 11, issue 7) contained a series of papers about diverse stewardship issues, each co-authored by scholars and practitioners from multiple disciplines and led by a non-ecologist. The goal of the workshop was to develop a more inclusive integrated framework for Earth Stewardship that would facilitate collaborative engagement across multiple disciplines and practices.

The participation of urban designers and engineers in the 2012 workshop and the issue of Frontiers described above symbolized the importance of interacting with professions that are engaged in the front lines of shaping the world in which we live. Sustainable or ecological approaches are becoming increasingly important to urban designers, regional planners, civil engineers, and those interested in restoring ecosystems that are embedded in urban territories. The fact that most of the world’s human residents already live in cities or other places classified as urban suggests that the various practitioners of urban design and planning will play important roles in promoting Earth Stewardship. Consequently, ecologists must engage with these professions in order to: (1) help shape the urban designs, rather than study the outcomes after the fact; and (2) learn how to engage better with the real estate industry, the developer community, and those who write and enforce zoning and building regulations. Working with urban designers can help insert ecological principles and knowledge into the process of urban, suburban, and rural “place making,” and may help formulate new procedures and regulations that are more attuned to the ecological processes that must be maintained or restored in sustainable urban areas (Felson et al. 2013; Felson and Pickett 2005; Pickett et al. 2013; Steiner et al. 2013). Professional societies such as the American Planning Association, the American Society of Landscape Architects, the Associated Collegiate Schools of Planning, and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture are examples of practitioner organizations through which mutually beneficial pursuit of Earth stewardship may exist. In 2013 and 2014, ecologists engaged with landscape architects in symposia at the American Society for Landscape Architecture annual meeting to offer examples of how to incorporate ecological science in landscape and urban design, not just in the design phase, but throughout the life of the built landscape in order to move toward sustainability goals. This joint ESA/ASLA effort is repeated at ESA annual meetings, building a community from both societies determined to work together to achieve lasting provision of ecological services.

In their 2010 meeting with ESA, leaders of eight Judeo-Christian groups expressed concern about sustainability and an interest in exploring ways to collaborate with ESA to foster Earth Stewardship. Unlike the meeting of social scientists, the religious leaders had explicit suggestions about how this might be done. They felt, in general, that they had no ready access to the environmental science community, which they felt looked down on religious groups. They questioned whether environmental advocacy groups would be unbiased sources of scientific information. They suggested three concrete steps: (1) preparing fact sheets or short YouTube-type videos on issues that would be of concern to the religious community, (2) initiating a speakers’ bureau that was co-trained by ecologists and by religious leaders to speak effectively to religious audiences, if invited to do so, and (3) an open letter from scientific and religious leaders to the religious community summarizing their common concern about the future. They emphasized that more progress would be made by focusing on issues of common concern (e.g., Earth Stewardship) than on issues that had a history of divisiveness (e.g., evolution). They also emphasized that issues of social and environmental justice would be of greater interest to religious groups than issues of environment. These conversations resulted in the development of a speakers’ bureau led by ESA member Greg Hitzhusen (http://www.esa.org/enjustice2/projects/faith-communities/).

ESA reached out to the business community in 2013 and continues to work toward lasting relations with business leaders around the world. Businesses are among the largest agents of environmental degradation in the world. This offers tremendous opportunities for companies to become agents for positive change. A growing number of companies around the world realize they can galvanize the global business community to create a sustainable future for business, society, and the environment. The first workshop held in 2013 (standing room only) brought together sustainability officers from large corporations with ecologists to address how the science of ecology can be put to use by corporations such as 3M and Weyerhauser in meeting their sustainability goals. The ESA workshop was followed by a meeting that included several ESA members at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) in London during the British Ecological Society Centennial Celebration in 2013 to explore how the science community can communicate more effectively with senior business leaders on sustainability issues. In 2014 a panel of business representatives convened to deepen the conversation between ESA members and business leaders, with a focus on businesses and biodiversity. Topics that remain to be explored include how business and industry view the need for biodiversity, what kinds of ecological information will enable businesses and industries to achieve sustainability goals that help preserve biodiversity, and what are the avenues for building collaborations between ecologists and businesses to protect biodiversity and the services it provides?

ESA is developing partnerships with public relations firms to help train ecologists in the art of effective communication with business leaders and has begun to develop a speakers’ bureau of ecologists with these skills. We hope to deepen our ties with public relations companies who can help spread the word regarding Earth Stewardship. These discussions and the above-mentioned Demonstration Project not only serve to expand the conversation of Earth Stewardship to audiences with real ability to enact lasting positive change in environmental practices, but they also identify career paths and opportunities for ecologists with businesses and organizations that are trying to meet sustainability goals of economy, environment, and equity.

In addition to outreach to communities of faith and business, ESA is developing collaborations via the arts and humanities. Currently, this effort is being led by the Long-Term Ecological Research Network via Ecological Reflections (http://www.ecologicalreflections.com/), an effort to link environmental science with the arts and humanities (Goralnik et al. (2015) in this volume [Chap. 16]). This effort led to environmental art exhibits at the 2012 and 2013 ESA Annual Meetings as well as temporary exhibits of environmental art at the National Science Foundation headquarters in Ballston, Virginia in 2012 and 2013. The goal of this collaboration is to connect environmental science and Earth Stewardship to the general public through the languages of the arts and humanities. Similarly, the 14th Cary Conference brought together philosophers, ethicists, religious scholars, and ecologists to explore the linkages among values, philosophy, and action and to explore a new framework for conversations about how to motivate and implement actions toward sustainability (Rozzi et al. 2013). That conference was an important steppingstone toward the present volume (see Introduction to this volume).

5 The Future of Stewardship at ESA

The growing interest in Earth Stewardship from the leadership and membership of ESA bodes well for future involvement of the Society in this area. Continued effort is clearly warranted; indeed, we consider it urgent. The wide range of scales at which stewardship can be approached allows individuals to be involved in a variety of ways and to identify activities that resonate personally. A spatially small scale, such as a local park, a backyard, or the area designated for a BioBlitz (see Box 12.1) can motivate some individuals, while others may find regional or global scales more compelling. The existence of many environmental organizations focused on watersheds, ranging in size from small neighborhood watersheds to the Chesapeake Bay watershed that encompasses six states plus the District of Columbia, exemplifies the range of scales at which a particular disciplinary approach to stewardship can be applied (Kingsland (2015) in this volume [Chap. 2]). ESA can continue to encourage involvement across a wide range of scales. Here, we highlight several directions that seem important and tractable.

5.1 Building Stronger Partnerships

Contemporary environmental challenges go well beyond science alone. ESA must continue to build strong partnerships with people and institutions that can effect change, finding key areas of commonality that reflect shared goals and making sure that ecological science is at the table. As with any ecosystem, particular components or linkages within the system may be highly influential, and identifying keystone institutions and leverage points is important. Linkages with other groups must broaden to include greater representation from the business community and politicians. An “us vs. them” attitude will not serve the goals of Earth Stewardship well, and many leaders are keenly interested in sustaining resources in their local environment. Actions that enhance sustainability may be good for the bottom line. Throughout the country, business and engineering schools are developing new degree programs and certificates in sustainability, and ESA could cultivate partnerships with such programs. The business community will remain influential, and technology will surely play a role in addressing stewardship issues. Developers should be encouraged to collaborate with ecologists during the early phases of land-development projects so that subsequent ecological problems (and litigation) might be minimized. Ecologists are not generally well schooled in how to develop such partnerships and engage effectively; ESA should assist its membership in developing these critical skills.

ESA can also encourage more interaction with specialized interest groups, such as societies devoted to fish and game species that are working to preserve or improve habitat for their particular species. For example, there are now some large organizations focused on conservation of trout and other salmonids, elk, deer, turkey, quail, and waterfowl. These organizations reflect the broader recognition of stewardship in society at large, although there are often tradeoffs among competing interests of different groups.

5.2 Science Communication

ESA should continue to enhance its leadership in science communication. The challenges of communicating ecological science within civil society remain profound, especially when some sectors of society consider scientific data to carry only the weight of an opinion. An ecologically literate citizenship is essential for achieving the goals of the Earth Stewardship Initiative. Thus, ESA must continue to help our members become more effective at communicating what we do, what we know, and most importantly, why it matters. ESA might develop more widespread communication training programs, perhaps modeled on the successful Leopold Fellows Program, targeted especially for graduate students and non-academic scientists that are not eligible for the Leopold Fellows Program. The ability to anticipate and use new communications media effectively will be key for these efforts. Earth Stewardship requires ecological literacy, and ecologists must be better at understanding their audiences in order to enter into dialogues that will result in more effective communication with the public at large. By partnering with other groups and engaging our younger scientists in the planning effort, ESA could make a major contribution to Earth Stewardship by directly enhancing the professional preparation of early-career ecologists.

5.3 Leading Theory Development in Sustainability Science

ESA members can also contribute to the theoretical basis for sustainability science. Historically ecologists have developed theory that integrates classical ecology with theory from evolutionary biology, molecular biology, geophysical sciences, etc. We are in early stages of integrating ecological theory with theory from various social sciences (Collins et al. 2011; Matson 2009) and currently lack a thoroughly developed theory for sustainability science. ESA can provide leadership to go beyond thinking of stewardship as “applied sustainability science” and rather to understand when and why (or why not) scientific understanding is effective in moving toward more sustainable pathways at various scales. Action ecology, such as ideas developed by the ESA student section, and discussions with practitioners need to become part of the learning loop for developing broader theory. Theory must be applied and tested against real societal and ecological problems. This remains a formidable challenge, but one that ESA is well positioned to nurture, perhaps by encouraging ESA sections to tackle relevant issues and by emphasizing sustainability theory in different venues during annual meetings.

5.4 Encouraging Personal Involvement

Ecologists can engage directly in stewardship activities that emerge from their research programs. There are many examples of academic scientists who have felt compelled to focus their efforts on conserving the species and habitat they study, after realizing that the subjects of their studies are rapidly disappearing. For example, the Golden-Lion Tamarin, an endemic primate in Brazil, is now the only primate species to have been upgraded in terms of its endangered species status, following prodigious efforts by researchers who spent most of their careers studying them (Kierulff et al. 2012). In other cases, scientists have advocated strongly for habitat connectivity on regional scales or for sustaining a key resource, such as fresh water, or for reducing pollution. These constitute another avenue by which current and future ESA members could become involved in Earth Stewardship activities that are personally important to them. Workshops at the annual meeting might include training in best practices for members to pursue stewardship related to their research.

Given the successes documented from previous ESA efforts, future ESA Presidents will likely choose to sharpen the Society’s focus on Earth Stewardship in different ways. Recent discussions with other professional societies whose expertise is related to stewardship have documented broad common interests that can be developed in the future. A recent effort by the ESA and the British Ecological Society to foster regular discussions among leaders of all the world’s ecological societies will provide an opportunity to interest a global audience of ecologists.

The changes that we ecologists have seen in less than a generation include remarkable advances in technology (e.g., computing power, global positioning systems, geographic information systems, sensor networks), rapid changes in global climate, a blossoming of quantitative analytical techniques, an explosion of information with the digital revolution, and a great increase in cross-disciplinary and international collaborations. The kinds of science that can be done have changed, and the training of new generations of ecologists must change accordingly. Amidst all these changes to our field, the natural world is also changing at an unprecedented rate. This set of circumstances puts ESA at a critical juncture where we have the opportunity to train future generations of ecologists to work effectively in a world that is fundamentally different from the one in which we grew up. Further, ESA must intensify efforts to partner with a wider range of institutions and become more active participants in problem-solving, recognizing that compromise is often necessary. Having realized these challenges and begun to respond, ESA must continue to embrace them.

References

AGU (2013) Helping audiences receive climate-science information: a message framework for scientists. Unpublished report

Bonilla NO, Scholl J, Armstrong M et al (2012) Ecological science and public policy: an intersection of action ecology. Bull Ecol Soc Am 93:340–345

Callicott JB (2015) The centennial return of stewardship to the Ecological Society of America. In: Rozzi R, Chapin FS III, Callicott JB et al (eds) Earth stewardship: linking ecology and ethics in theory and practice. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 161–171

Chapin FS III, Fernandez E (2013) Proactive ecology for the Anthropocene. Elementa. doi:10.12952/journal.elementa.000013

Chapin FS III, Power ME, Pickett STA et al (2011) Earth stewardship: science for action to sustain the human-earth system. Ecosphere 2(8):art89 doi:10.1890/ES11-00166.1

Chapin FS III, Kofinas GP, Folke C (eds) (2009) Principles of ecosystem stewardship: resilience-based natural resource management in a changing World. Springer, New York

Christensen NL, Bartuska AM, Brown JH et al (1996) The report of the Ecological Society of America committee on the scientific basis for ecosystem management. Ecol Appl 6:665–691

Clark WC, Dickson NM (2003) Sustainability science: the emerging research program. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(14):8059–8061

Clark WC, Levin SA (2010) Toward a science of sustainability. Princeton Environmental Institute, Princeton

Collins SL, Carpenter SR, Swinton SM et al (2011) An integrated conceptual framework for long-term social-ecological research. Front Ecol Environ 9:351–357

Colón-Rivera RJ, Marshall K, Soto-Santiago FJ et al (2013) Moving forward: fostering the next generation of Earth stewards in the STEM disciplines. Front Ecol Environ 11:383–391

Conradie E (2006) Christianity and ecological theology: resources for further research. Sun Press, Stellenbosch

DeFries R, Ellis E, Chapin FS III et al (2012) Plantetary opportunities: a social contract for global change science to contribute to a sustainable future. BioScience 62(6):603–606

Ellis EC, Ramankutty N (2008) Putting people on the map: anthropogenic biomes of the world. Front Ecol Environ 6(8):439–447

Felson AJ, Pickett STA (2005) Designed experiments: new approaches to studying urban ecosystems. Front Ecol Environ 3:549–556

Felson AJ, Bradford MA, Terway TM (2013) Promoting Earth stewardship through urban design experiments. Front Ecol Environ 11:362–367

Foley JA, DeFries R, Asner GP et al (2005) Global consequences of land use. Science 309:570–574

Goralnik L, Nelson MP, Ryan L et al (2015) Arts and humanities efforts in the US Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) network: understanding perceived values and challenges. In: Rozzi R, Chapin FS III, Callicott JB et al (eds) Earth stewardship: linking ecology and ethics in theory and practice. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 249–268

Hargrove E (2015) Stewardship versus citizenship. In: Rozzi R, Chapin FS III, Callicott JB et al (eds) Earth stewardship: linking ecology and ethics in theory and practice. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 315–323

IPCC (2014) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Working group II contribution to the IPCC 5th assessment report. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kates RW, Clark WC, Corell RW et al (2001) Sustainability science. Science 292(5517):641–642

Kearns L, Keller C (2007) Eco-spirit: religions and philosophy for the Earth. Fordham University Press, New York

Kierulff MCM, Ruiz-Miranda CR, de Oliveira PP et al (2012) The Golden lion tamarin Leontopithecus rosalia: a conservation success story. Int Zoo Yearb 46(1):36–45

Kingsland SE (2015) Ecological science and practice: dialogues across cultures and disciplines. In: Rozzi R, Chapin FS III, Callicott JB et al (eds) Earth stewardship: linking ecology and ethics in theory and practice. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 17–26

Lubchenco J (2012) Reflections on the sustainable biosphere initiative. Bull Ecol Soc Am 93:260–267

Lubchenco J, Olson AM, Brubaker LB et al (1991) The sustainable biosphere initiative: an ecological research agenda. Ecology 72:371–412

Marshall K, Hamlin J, Armstrong M et al (2011) Science for a social revolution: ecologists entering the realm of action. Bull Ecol Soc Am 92:241–243

Matson PA (2009) The sustainability transition. Issues Sci Technol 25(4):39–42

May Jr RH (2015) Andean llamas and earth stewardship. In: Rozzi R, Chapin FS III, Callicott JB (eds) Earth stewardship: linking ecology and ethics in theory and practice. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 77–86

MEA (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being: current status and trends, vol 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Melillo JM, Richmond TC, Yohe GW (eds) (2014) Climate change impacts in the United States: the third National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC

Muñoz-Erickson T, Aguilar-Gonzáles B, Loeser MR et al (2009) A framework to evaluate ecological and social outcomes of collaborative management: lessons from implementation with a northern Arizona collaborative group. Environ Manage 45:132–144

NRC (1999) Our common journey: a transition toward sustainability. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

NRC (2010) America’s climate choices: adapting to the impacts of climate change. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Odum EP (1989) Ecology and our endangered life-support systems. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland

Palmer M, Bernhardt E, Chornesky E et al (2004) Ecology for a crowded planet. Science 304:1251–1252

Palmer MA, Bernhardt ES, Chornesky EA et al (2005) Ecological science and sustainability for the 21st century. Front Ecol Environ 3:4–11

Pickett STA, Cadenasso ML, McGrath M (eds) (2013) Resilience in ecology and urban design: linking theory and practice for sustainable cities. Springer, New York

Power ME, Bouma-Gregson K, Higgins P, Carlson SM (2015) The thirsty eel: summer and winter flow thresholds that tilt the eel river of northwestern California from salmon-supporting to cyanobacterially degraded states. Copeia 103(1) (in press)

Power ME, Chapin FS III (2009) Planetary stewardship. Front Ecol Environ 7(8):399

Ramos J, Lymn N, Salguero-Gomez R et al (2012) Ecological Society of America’s initiatives and contributions during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Bull Ecol Soc Am 93:115–116

Rivera N, Calderon-Ayala J, Calle L et al (2010) Multidisciplinary and multimedia approaches to action-oriented ecology. Bull Ecol Soc Am 91:313–316

Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K et al (2009) A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461:472–475

Rozzi R, Pickett STA, Palmer C et al (eds) (2013) Linking ecology and ethics for a changing World: values, philosophy, and action. Springer, Dordrecht/Heidelberg/New York/London

Sayre N (2005) Working wilderness: the Malpai Borderlands Group and the future of the western range. Rio Nuevo Press, Tucson

Sayre NF, Kelty R, Simmons M et al (2013) Invitation to earth stewardship. Front Ecol Environ 11:339

Silbert S, Chandler G, Nabhan GP (eds) (2007) Five ways to value working landscapes of the West. Center for Sustainable Environments, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff

Sisk TD (2010) Ranching, local ecological knowledge, and the stewardship of public lands. In: Power ME, Chapin FS III (eds) Planetary stewardship in a changing world: paths toward resilience and sustainability. Bull Ecol Soc Am 91(2):150–152

Sisk TD, Albano CM, Aumack EA et al (2010) Integrating restoration and conservation objectives at the landscape scale: the Kane and Two-mile Ranch project. In: van Riper C III, Wakeling BW, Sisk TD (eds) The Colorado Plateau IV: shaping conservation through science and management. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, pp 45–66

Steffen WL, Sanderson A, Tyson PD et al (2004) Global change and the Earth system: a planet under pressure. Springer, New York

Steffen W, Jansson Å, Deutsch L et al (2011) The Anthropocene: from global change to planetary stewardship. Ambio. doi:10.1007/s13280-011-0185-x

Steiner F, Simmons M, Gallagher M et al (2013) The ecological imperative for environmental design and planning. Front Ecol Environ 11(7):355–361

Stern N (2007) The economics of climate change: the Stern review. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Szaro RC, Johnson ND, Sexton WT et al (eds) (1999) Ecological stewardship: a common reference for ecosystem management. Elsevier, Oxford

Turner BL II, Kasperson RE, Matson PA et al (2003) A framework for vulnerability analysis in sustainability science. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100(14):8074–8079

UN (2010) The millennium development goals report 2010. United Nations, New York

WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development) (1987) Our common future. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Yoshiyama RM, Moyle P (2010) Historical review of Eel River Anadromous Salmonids, with emphasis on Chinook salmon, Coho salmon and steelhead. Report for California Trout. 1–107, Center for Watershed Sciences, University of California, Davis

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff, governing board, and members of the Ecological Society of America, especially Executive Director Katherine McCarter, for their engagement in crafting and implementing ESA’s Earth Stewardship Initiative. We also thank Baird Callicott, Cliff Duke, Katherine McCarter, and Teresa Mourad for their careful review of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chapin, F.S. et al. (2015). Earth Stewardship: An Initiative by the Ecological Society of America to Foster Engagement to Sustain Planet Earth. In: Rozzi, R., et al. Earth Stewardship. Ecology and Ethics, vol 2. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12133-8_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12133-8_12

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-12132-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-12133-8

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)