Abstract

As collaborative groups gain popularity as an alternative means for addressing conflict over management of public lands, the need for methods to evaluate their effectiveness in achieving ecological and social goals increases. However, frameworks that examine both effectiveness of the collaborative process and its outcomes are poorly developed or altogether lacking. This paper presents and evaluates the utility of the holistic ecosystem health indicator (HEHI), a framework that integrates multiple ecological and socioeconomic criteria to evaluate management effectiveness of collaborative processes. Through the development and application of the HEHI to a collaborative in northern Arizona, the Diablo Trust, we present the opportunities and challenges in using this framework to evaluate the ecological and social outcomes of collaborative adaptive management. Baseline results from the first application of the HEHI are presented as an illustration of its potential as a co-adaptive management tool. We discuss lessons learned from the process of selecting indicators and potential issues to their long-term implementation. Finally, we provide recommendations for applying this framework to monitoring and adaptive management in the context of collaborative management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Collaborative natural resource management is an increasingly popular approach for addressing public land conflicts (Brick and others 2001). Academics and managers alike view collaborative processes as promising in leading to just and sustainable outcomes because the involvement of stakeholders, including those with little power, is more likely to yield better planning and policy outcomes (Innes and Booher 1999), as well as increase learning and adaptability of socio-ecological systems (Armitage 2005; Olsson and others 2004). Here we understand successful collaborative processes to be those most able to integrate and manage multiple stakeholder interests and knowledge, build trust and foster social learning, develop mutually-agreeable solutions, and lead to desired environmental conditions and social well-being. Much has been written in the literature about the procedural and social factors leading to an effective collaborative process (see Tilt and others 2008; Wondolleck and Yaffee 2000; Sabatier 2005; Leach and Pelkey 2001; Moote and McClaran 1997; Daniels and Walker 1996). Yet, there is little empirical evidence that these processes lead to better ecological and social outcomes, than traditional approaches—indeed it is unclear how often collaboration leads to substantive decisions that can be implemented at all. This uncertainty has raised criticisms about the long-term effects of collaborative processes (see Kenney 2000 and McCloskey 1996). In addition, frameworks that examine both effectiveness of the collaborative process and its outcomes are poorly developed or altogether lacking.

The concept of ecosystem health is appropriate for evaluating ecological and social outcomes of collaboratives because it bridges natural and social criteria, while integrating values and perceptions that are inseparable parts of management (Aguilar 1999; Muñoz-Erickson and others 2007). Ecosystem health acknowledges societal values in defining future desired conditions while relying on scientific criteria (Steedman 1994). For collaboratives that address the challenges of balancing both ecological and socio-economic objectives, particularly in landscapes comprising mixed public and private ownership, a framework that incorporates societal values is of great importance.

This article presents a framework to evaluate the process and outcomes of the collaborative management approach on socio-ecological systems. Specifically, we present the holistic ecosystem health indicator (HEHI) as a tool to assess and monitor on-the-ground ecological and social outcomes of a collaborative land management group, the Diablo Trust, operating on mixed private and public lands southeast of Flagstaff, AZ. The development of the HEHI framework for the Diablo Trust was the result of an extensive stakeholder participation process, carried out in multiple phases, to ensure that knowledge needs are met through the use of a multi-party monitoring approach. We developed the HEHI for the Diablo Trust during the Phase 1 of this project. This phase consisted of an iterative participatory process beginning in 2001 through 2004 in which we incorporated stakeholder input in the initial selection and prioritization of indicators, a process described in further detail in Muñoz-Erickson and others (2007). We turned this process into a comprehensive monitoring program, the IMfoS (Integrated Monitoring for Sustainability) Program that is now supported by multiple agencies and organizations and managed by the Diablo Trust.

A long-standing collaborative research relationship with the group has allowed us to lead this stakeholder-driven process of indicator selection while maintaining the researcher’s reflective independence. The Diablo Trust has applied and tested sustainable management goals, monitoring efforts, and holistic decision-making for the last 12 years. Their well-defined efforts and continued evolution makes this group a useful case study to implement the HEHI under a collaborative management paradigm. It is important to note, however, that the indicator results presented here are not an evaluation of current trends in socio-ecological conditions; rather, they establish an initial baseline for identifying temporal changes in the future, as they pertain to the Diablo Trust’s goals and desired conditions. Although we present and discuss monitoring results, our primary goal in this article is to convey insights from the collaborative stakeholder process used to implement the comprehensive monitoring program developed during Phase 2 of this project.

The objectives of this article are to present the process for developing and implementing the HEHI for an existing collaborative management group, and to identify factors promoting or limiting the ability of a collaborative to implement the HEHI framework in a manner that enhances its ability to advance goals of social and ecological sustainability. To this end, after presenting the HEHI framework and results from of its first application with the Diablo Trust, we evaluate the utility of the HEHI based on direct observations implementing the tool as well as on stakeholders’ attitudes and level of support. We then present lessons learned from this experience, specifically regarding the multi-party monitoring process, the trade-offs involved in doing monitoring, the use of information by the collaborative, and the role of the HEHI as a tool in an adaptive management process. While long-term monitoring of indicators is necessary to establish trends directly associated with management actions, and hence evaluate the effectiveness of these efforts, the results from the first application of this framework reveal two of the greatest challenges to evaluating outcomes: defining appropriate measures of success based on both scientific and local knowledge, and articulating values and processes to guide decision-making.

The Holistic Ecosystem Health Indicator (HEHI)

According to an ecosystem health definition, a “healthy” collaborative can be defined as a socio-ecological system that is “stable and sustainable”, maintaining its organization and autonomy over time and its resilience to stress, while remaining economically viable (Costanza 1992; Rapport 1995). To measure and evaluate system health and sustainability, the use of indicators is common yet varied across many disciplines (Hezri and Dovers 2006). Most efforts to develop indicators for sustainability are relevant at national and international scales as in, for example, the United National Development Program (UND) Human Development Index and the Environmental Sustainability Index (Fraser and others 2006). However, some authors argue that local-scale indicators, organized around a concept that the public understands, are necessary to engage stakeholders in defining sustainability goals and developing information that is relevant at the local level (Norton 2005). In addition, Reed and others (2006) propose that local-scale indicators can stimulate a process of enhancing understanding of environmental and social processes and facilitate community building. Ecosystem health indicators are useful in this sense because their practical application involves the identification of site-specific ecological and social endpoints of “health” and the development of relevant indicators that measure progress towards these endpoints.

Given the place-based focus of community-based collaboratives, we selected an ecosystem health indicator framework that was developed and applied to measure performance of managed ecosystems at the local scale. The holistic ecosystem health indicator (HEHI) is an interdisciplinary framework that quantifies ecological, social, and interactive indicators of the health of ecosystems (Aguilar 1999). This framework has been applied extensively to evaluate the sustainability of managed ecosystems in Costa Rica, but these efforts have been developed and implemented through an expert-based approach. Therefore, in addition to the central objective of developing a practical, integrated monitoring approach for the Diablo Trust, another motivation for this study was to develop the HEHI through a bottom-up, stakeholder-led effort in which indicators are selected and their values are interpreted through a collaborative process (Muñoz-Erickson and others 2006, 2007).

The hierarchical structure of the HEHI includes three main branches: ecological, social and interactive (Fig. 1). The ecological branch of the HEHI organizes data that describe conditions and trends in the ecosystem. This branch provides a “big-picture” perspective of ecological health across the entire landscape. The social branch organizes socioeconomic information about the communities in and around the management unit. This branch focuses on the social and economic health of the primary residents in the area, and on the collaborative group as a forum for community dialog and interaction. Finally, the interactive branch addresses the key socio-ecological linkages, represented by land use practices, management decisions, and public engagement, as well as outcomes of the collaborative process. This last branch addresses the direct pressures that threaten the ecosystem, and assesses whether management decisions by the collaborative group and associated land management agencies effectively address those pressures. The benefits that people obtain from the land, such as through recreation, food production, and wildlife conservation, are also tracked in this branch. In this way, the interactive branch allows for systemic monitoring of the socio-ecological system as one unit, an aspect that is lacking in most sustainability indicator programs. Each branch is sub-divided into categories which further operationalize the meaning of each branch. The categories are comprised of indicators which are carefully selected to evaluate specific conditions and trends of the socio-ecological system (Aguilar 1999). In order to ensure that this approach captures site-specific conditions and the values of the Diablo Trust, we applied a participatory methodology (described in the next section) to guide the indicator selection, sampling strategy, and protocol development (Muñoz-Erickson and others 2007).

Structure of the Holistic Ecosystem Health Indicator (HEHI). Adapted from Muñoz-Erickson and others (2007)

Diablo Trust Case Study

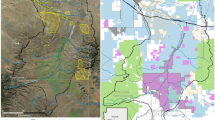

The Diablo Trust management unit is 170,000 ha in size and is located within Coconino County, about 64 km southeast of Flagstaff, Arizona (Fig. 2). Average precipitation in the west-southwest portion is 203–610 mm and declines with elevation towards the east-northeast to 51–254 mm, and elevation ranges from 793 m to 2317 m. The management unit includes a wide range of semi-arid vegetation types, from ponderosa pine forests and pinjon-juniper woodlands, to lower elevation grasslands and shrublands. The diversity of vegetation types throughout the area supports a variety of wildlife species, including numerous game species valued highly by the public, such as rocky mountain elk, mule deer, and American pronghorn. The area also has a high diversity of birds, small mammals, reptiles and fish species.

Map showing the boundary of the 170,000 ha Diablo Trust in the southeast corner of Coconino County, Arizona. The unit is surrounded by the Navajo Reservation on the north, the cities of Flagstaff and Winslow on the west and east corners, respectively, the Coconino National Forest on the west boundary, state and private land and the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest on the east boundary, and the Mogollon Rim along the southern boundaries. Source: Diablo Trust (1999)

The Diablo Trust management unit includes 58% federal lands 22% state lands, and 20% private property, and the entire area is owned or leased by two large ranches, the Flying M and Bar-T-Bar. Participants in the Diablo Trust include the ranchers, federal, state, and local agencies (e.g. US Forest Service, Arizona State Land Department, Arizona Game and Fish Department, and US Natural Resource Conservation Service), as well as, university researchers, environmental activists, other ranchers from around the area, and concerned citizens. In 1993, the Diablo Trust developed a programmatic management plan, entitled “The Diablo Trust Area Range Management Plan and Proposed Action”, that states desired conditions for both the public and private lands (Diablo Trust 1999). This plan includes various prescriptions appropriate to each of its six major biological zones, with each zone containing characteristic plant and animal communities that can be managed using similar management tools. The zones are managed for multiple purposes, including cattle grazing, recreation, hunting, fishing, wildlife management, forest health, and watershed protection.

Written as a 3-part holistic goal, the long-term goals and management strategies accommodate sustainable use and conservation of resources along with commodity production (e.g. beef, fire wood). The overarching goal statement incorporates specific goals for quality of life, production, and future landscape and resource base (Diablo Trust 1999).

In general, the goals for quality of life and forms of production provide guidance as to the information necessary for the social and interactive branches of the HEHI. The Diablo Trust is concerned for the quality of life of the ranches, the collaborative group, and the community in general. The goal of production is guided by the desire of the ranches to continue to serve as the foundation for sustainable long-term health of the Diablo Trust lands (Diablo Trust 1999). The objective of these goals is to manage the 170,000 ha of mixed-ownership land as a whole, guided by the future landscape goals and specific objectives outlined in their management plan, along with regulatory management objectives for the public lands as defined by the administrative agencies. The future landscape and resource base goals describe the vision, or desired conditions, for the ecosystem and for the stakeholders that comprise the collaborative group. Similarly, the future human resource base goals of the Diablo Trust guide their vision for collaboration and the attainment of a healthy relational base among stakeholders in the management of the land. In this way, the plan also established the decision-making process that the Diablo Trust uses to come to agreement on actions intended to achieve goals and objectives. This process is guided by an organizational structure that tasks working committees to develop activities that meet these goals, guided by an Executive Committee and Board of Directors composed of a representative mix of Diablo Trust stakeholders. These committees meet regularly to oversee day-to-day activities and the entire group meets openly every month to share progress and decide on future directions. This process is meant to be adaptive, with an emphasis on monitoring to evaluate progress and to inform future decision-making.

Understanding how this structure supports monitoring requires background on the IMfoS approach. To gauge and quantify the performance of indicators in the HEHI for the Diablo Trust, we assigned a weighted score and desired value (see Figs. 3, 4 and 5), or benchmark, for each indicator based on a combination of scientific criteria, management objectives, and stakeholders’ knowledge and evaluation. We used the rating scale originally developed by Aguilar (1999), which ranks indicators and assigns points from a possible 1000 total points, as measures of high, middle and low ecosystem health, based on a combination of management and practical considerations, including data availability, data quality, and sampling considerations. We modified the point distribution for the Diablo Trust according to the relative importance of the indicator to the health of the ecological and social system and the management goals identified through the stakeholder process (Muñoz-Erickson and others 2007). Diablo Trust participants evaluated the points and benchmarks for each indicator, which in some instances involved negotiation until the group reached a value that they could agree on. The use of 1000 points is a subjective rating scale, yet its implementation through previous applications in the past has tended to validate its utility (Aguilar 1999). While other rating scales could be used to distribute points among indicators, the 1000 point scale was useful for the Diablo Trust context because it is large enough to accommodate a large number of indicators desired by the collaborative, and to distribute the points allocated to each indicator in a way that is clear to multiple users.

Final categories, indicators, and allocated points of the ecological branch, resulting from the participatory process to develop the HEHI for the Diablo Trust collaborative group. The pie chart and column for possible points show the weightings assigned to each category and indicator, respectively, out of the total allocation of 1000 points. The points received are based on the values of each indicator, compared to the indicator benchmarks (see text for detailed explanation)

Final categories, indicators, and allocated points of the social branch, resulting from the participatory process to develop the HEHI for the Diablo Trust collaborative group. The pie chart and column for possible points show the weightings assigned to each category and indicator, respectively, out of the total allocation of 1000 points. The points received are based on the values of each indicator, compared to the indicator benchmarks (see text for detailed explanation)

Final categories, indicators, and allocated points of the interactive branch, resulting from the participatory process to develop the HEHI for the Diablo Trust collaborative group. The pie chart and column for possible points show the weightings assigned to each category and indicator, respectively, out of the total allocation of 1000 points. The points received are based on the values of each indicator, compared to the indicator benchmarks (see text for detailed explanation)

In the summer of 2005, the group (including our research group, students, and Diablo Trust volunteers) collected primary data for vegetation and soil quality indicators at established monitoring locations for each vegetation zone across the Diablo Trust unit. Secondary data for watershed health, primary productivity and wildlife were compiled from various agencies and research institutions. Data for the social branch categories consisted of a combination of primary and secondary data. Primary data were obtained from surveys administered to local community residents, both permanent and seasonal residents, and participants involved in the Diablo Trust (for the collaborative process-social outcomes category, see below). Secondary data were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau. Similarly for the interactive branch, primary data came from a survey distributed to local permanent and seasonal residents, and to participants of the Diablo Trust. Secondary data, for the land use practices category, were obtained from the various management agencies mentioned previously.

Once data were collected for all indicators, the research team summarized those results, largely through the use of descriptive statistics. We then compared these results to the benchmarks adopted a priori for each indicator, and we assigned the points according to how well these results met the desired target. If the results for one indicator met or exceeded the benchmarks, it received all possible points, but if it fell below the benchmark it received only a portion of the points. As an example of indicator valuation we describe the procedure for point allocation for the compaction indicator in the soil quality category of the ecological branch. In this example, a total of 20 measurements were collected at random locations at each monitoring point, using a soil penetrometer, and the number of samples that fell within each of the benchmark categories was assigned a weighted average of the initial points for that indicator. For instance, more points were given for locations with low compaction (measures of 0–2 kg/cm, N = 5), with fewer points given for locations showing intermediate compaction (measurements of 2.1–3 kg/cm, N = 13) and no points for locations with measures greater than 3 kg/cm (N = 2). The final score for the compaction indicator is a sum of the points earned after weighing the samples according to these benchmarks.

Once similarly derived scores were assigned to each indicator, we summed the points to obtain a total for each category. We then summed totals from the three branches to obtain an overall HEHI score. For the ecological branch, the categories exhibiting best performance were soil quality (89.9% total for that category; Fig. 3) and primary productivity (100%; Fig. 3). Watershed health showed intermediate values (72.4%; Fig. 3), while vegetation and wildlife were the weakest areas of this branch (46.5% and 33.8% respectively; Fig. 3). For the social branch, the income and demographics categories received the highest indicator scores (76.6% and 71.4% respectively; Fig. 4), while economic stability (40.6%; Fig. 4), community strength (57.4%; Fig. 4), and collaborative process—social outcomes (54.3%; Fig. 4) received the lowest scores. Finally, in the interactive branch, the collaborative process—management outcomes performed best (84.0%; Fig. 5), followed by land use practices (50.4%; Fig. 5) and public attitudes toward land uses (50.30%; Fig. 5), while the implementation of management actions received a low score (47.01%; Fig. 5).

These values, however, reflect the comparisons of data collected with “benchmark” values derived from the literature and discussions with subject-matter experts and Diablo Trust stakeholders, and thus they are, at best, first approximations of areas of strength and weakness in this socio-ecological system. Future monitoring efforts will allow an evaluation of true temporal trends and examination of the effects of management actions. The lack of historical data currently limits analysis and precludes completion of a full adaptive management cycle. Therefore, as we discuss later in this article, we consider the results presented here to be illustrative of future applications and caution more detailed evaluation of results would be premature. Nonetheless, we note how this initial progress already has influenced the work of the Diablo Trust.

Methods

In Phase 2, the focus of this article, stakeholders refined and implemented indicators through a series of workshops and field efforts held between 2005 and 2006, under the IMfoS program umbrella. The purpose of the workshops was to involve stakeholders who had participated in Phase 1 in the refinement and adoption of monitoring protocols, to ensure that the structure and implementation of the HEHI met stakeholder needs. Two half-day workshops and numerous smaller meetings involved ranchers, environmentalists, scientists, and representatives from the management agencies. Participants deliberated over each indicator, its proposed protocols and indicator weights. The process was open, and each participant was able to evaluate the utility and validity of each indicator, all of which were subsequently adopted, modified, or eliminated by the entire group. As part of these efforts, stakeholders also reviewed the results of the first round of monitoring, including earlier versions of this manuscript. The secondary purpose of Phase 2 was to finalize the transfer of the methodology to stakeholders through testing of the utility of the indicators and the sampling protocols.

To assess the utility of the HEHI and the monitoring process, we employed participant observation methods during the workshops as well as outside the workshops, through informal exchanges, field work, and social events structured around monitoring. We documented observations through meeting and field notes under these general categories: negotiation and mutual acceptance of indicators, evaluative criteria, and monitoring (points of dissent and convergence); ability to see the big picture and the socio-ecological context through the use of the HEHI; trust and credibility on the researchers; awareness and reflection on Diablo Trust management and monitoring goals; commitment and ownership potential from the different parties, including agencies; and the utility of the HEHI as an adaptive management tool. We augmented this evaluation with an assessment of stakeholders’ confidence of the HEHI using a survey distributed before and after the multiparty monitoring workshops to assess changes in their understanding and acceptance of the tool. We used a closed-ended questionnaire of 11 statement items, with agreement indicated by “Yes”, “No”, or “Not Sure” responses. The questions covered cost, time investment, and relevance of monitoring data to the collaborative’s goals and stakeholders’ needs. We analyzed these data using descriptive statistics to compare the percentage of people that agreed with survey statements, and to evaluate changes in the survey responses between the first workshop in November 2004, and after implementation of the HEHI and final workshop in January 2006. The survey sample was complete in that it included all stakeholders that participated in the workshops. Although sample sizes are small (n = 9 for 2004 workshop, and n = 10 for the 2006 workshop), they are not unusual for case study approaches that focus on key participants (Yin 1992) and were representative of the different constituencies that are members of the Diablo Trust. Nonetheless, the small sample size does not allow for statistically testing differences between the first and the second year, therefore results should be interpreted as trends and not absolute changes.

Results and Lessons Learned

Results from surveys showed improvement in stakeholders’ perceived utility of the HEHI and support for its implementation across Diablo Trust lands. Of the 11 issues surveyed, 8 showed improved stakeholder support between the 2004 and 2006 workshops (Table 1). Prior to implementation, 33% of stakeholders thought that the tool provided the information needed to guide management in a manner that would move the Diablo Trust closer to its 3-part holistic goal. This number increased to 60% following implementation in 2006. Following the implementation of the HEHI and final IMfoS workshops, more stakeholders agreed that the HEHI improved communication (80% in 2006 vs. 56% in 2004), and working relationships among stakeholders (60% vs. 33%). Responses also indicated that stakeholders believed the HEHI reduced time and effort allocated to monitoring by eliminating redundancy and improving upon less efficient methods (70% vs. 33%) and that it is effective at integrating existing and new monitoring data (70% vs. 56%). Support for other items was fairly consistent between the workshops (Table 1).

Results from stakeholder surveys also showed a slight decline in stakeholder agreement that the HEHI provided information that fulfills agency requirements (90% in 2006 vs. 100% in 2004), and that it can reduce the potential of future conflict or litigation (70% vs. 89%). These results are consistent with concerns expressed by some stakeholders regarding the legal consequences of any change to existing monitoring programs. Of greater concern, agreement barely changed before and after implementation (33% to 30%) that the HEHI improved the ability of the Diablo Trust to learn from monitoring data and use the information to adjust management goals (active adaptive management), an apparent contradiction to the results presented above, and which we discuss later in this article.

A number of key issues and lessons learned emerged directly from participant observations of the case study, including:

(1) Approaches to developing and implementing indicators: stakeholder input vs. multi-party monitoring. One of the most important outcomes of this project was the bottom-up process of selecting indicators because it not only helped define ecosystem health for this area, but it did so in the context of collaboration. We used two approaches with differing levels of stakeholder involvement, each with its distinct advantages and disadvantages. For Phase 1 of the process, where we guided the indicator selection process and incorporated stakeholder input through interviews and expert consultation, there was utility in including multiple sources of knowledge and values, while maintaining the researcher’s reflective independence. It helped alleviate unrealistic needs for time investment by stakeholders, since most of the background and integration work for the indicators is done by the researchers, while the stakeholders are involved at key points in prioritizing the indicators. However, we had the advantage that the Diablo Trust already had a well-developed management plan, desired conditions, and monitoring goals, all articulated, to varying degrees of sophistication, in documents available to us. In addition, a high level of trust among collaborators had been previously established, and the interviews and meetings further fomented this trust throughout the process. Other collaboratives, especially those initiating their process and starting to develop a management plan, may benefit from having stakeholders more involved in the indicator selection process, as this will help develop the effectiveness of stakeholder participation in the difficult task of monitoring program development (Fernández-Giménez and others 2006).

The multi-party monitoring process we used for the IMfoS phase was effective at elucidating significant challenges to the social capital and power structure of the Diablo Trust. Through workshops, stakeholders were more intimately involved in the final prioritization of indicators and refinement of the tool, but internal tensions were exposed. Stakeholders showed varying degrees of comfort with increased access to data and appropriate desired conditions despite broad participation in their articulation several years previously. This also meant that more time was spent in addressing differences over specific controversial indicators, rather than debating the HEHI as a whole. Thus, we weren’t able to narrow down the list of indicators as much as we had hoped, and in some cases we had to expand it. Nonetheless, this intensive process was necessary for bringing these issues to the surface, agreeing on indicators to implement, and engaging all parties in the monitoring process. It also helped set in motion a commitment for long-term collaboration in carrying out the monitoring protocols. The overall improvement in stakeholder’s perspectives before and after implementation indicates that the multi-party monitoring workshops may have influenced stakeholder support of the HEHI and monitoring process.

(2) Use of information: dispute over values or facts? A key characteristic of collaborative management is that it creates the space for mutual learning and sharing of information and knowledge, as well as elucidating the values and attitudes that stakeholders have towards resources and their use (Daniels and Walker 1996; Wondolleck and Yaffee 2000). However, the distinction between what are facts and values is often not clear (Tilt and others 2008). We found this to also be the case in the process of selecting indicators with the Diablo Trust, as disagreements regarding monitoring data, and values and attitudes towards the land, were often indiscernible.

Underlying these disagreements was a general concern about how monitoring data might be used and abused, and how they should be interpreted and evaluated. It is not uncommon for ranchers to be skeptical about how data are used, and for them to want information about grazing practices and their impacts to remain private (Fernández-Giménez and others 2006), especially when there is a long history of conflict, fueled by selective use of information to meet political objectives. We made progress on this issue in two important ways. First, throughout the workshops the ranchers discussed this fear openly and validated the importance of scientific information, along with their own knowledge, to advance the overall goals of the collaborative. Some of the ranchers agreed to share private economic information if we could present the results of analysis in a discreet manner. The HEHI addressed this by presenting the information in a summarized form, without revealing the raw data used do derive values for the relevant indicators.

Secondly, the participation of the agencies at the workshops was critical to clarifying differences in monitoring goals and protocols, which has long been a source of tension. Agencies were able to better understand the ambivalence that stakeholders, especially the ranchers, have towards public examination of monitoring information. Agency participation also helped build a stronger monitoring partnership through on-the-ground collaboration in data collection and agreement to seek ways to integrate HEHI monitoring data with the data they are required, by law, to collect. Survey results confirm this, with overall support for the idea that the HEHI tool has potential for reducing future conflicts and litigation, improving communication among stakeholders, and fostering strong working relationships between agencies and the collaborative in decision making.

(3) Balancing tradeoffs: Simple vs. complex, practicality vs. rigor, cost vs. time investment. Capturing and evaluating system complexity is by nature a complex undertaking. Therefore, tradeoffs are necessary in implementing the HEHI or any monitoring tool. The complexity of the effort will determine the nature of these tradeoffs, which typically pit consideration of long-term simplicity, practicality, and cost against the often daunting information needs of managers responsible for complex social and ecological systems. Consequently, it is important that the process of selecting indicators yields a manageable list with the minimum number of indicators needed to capture sufficient system complexity. Establishing this balance is very challenging and requires time and flexibility in the process. We used numerous avenues and methods to incorporate stakeholder input (e.g. interviews, conceptual models, workshops), and although we expect that the list of indicators will slim down in the future, this process was already useful in distilling a “laundry list” of candidate indicators into a shorter list of variables (from an initial list of 170 candidates to a final suite of 51 indicators). Additionally, although processing such information was challenging for stakeholders at first, we found it necessary and enlightening to develop a shared understanding of what we know and don’t know, prior to narrowing down the suite of indicators. Indeed, survey results show that this process was useful in increasing stakeholder support for the monitoring program and in increasing understanding of the ecological and social variables.

While the workshops allowed for the refinement and elimination of some indicators, the resulting plan retained a level of complexity that required a large data collection and analysis effort. Greater time and cost efficiencies may be gained by eliminating indicators that, in the future, are found to yield poor, redundant, or unnecessary information. Utilizing existing data sources from government agencies and other researchers reduced time and cost, but introduced quality control issues that demanded the researchers’ time and attention. Data sharing, where quality could be assured, had the added value of integrating disparate data sources and increasing buy-in from some collaborating agencies and organizations. In addition, where possible we adopted data collection methods similar to those employed by agencies, especially in cases where sampling was particularly time consuming, as is the case for most vegetation indicators. By using comparable methods we were able to share resources with the agencies, to mutual benefit.

(4) The role of the HEHI as a tool for adaptive co-management. A main objective of this study was to assess the utility of the HEHI as an adaptive management tool to monitor outcomes of collaborative management. Feedback loops that link monitoring and management goals are at the crux of successful adaptive management (Moir and Block 2001). As mentioned above, when working with the Diablo Trust, we found that multiple iterations of the HEHI development effort were necessary to refine the tool, and that this revisiting of key themes led the collaborative to adjust management goals. Furthermore, this iterative process reinforced a commitment to adaptive management (not a trivial issue), as it required considerable deliberation to embrace the idea that management actions should change if monitoring data indicate that they are not leading to favorable outcomes. This commitment is central to adaptive management, but it remains elusive in practice. We found that it was easy to agree to adaptive management, in concept, but more difficult to commit to a data-driven decision process in advance, even in this case where collaborators were operating in a well-known landscape and could draw on established personal and institutional relationships. Although the iterative process described above allowed the collaborative to work through these issues, the next real test of the HEHI, in future years, will be assessing the ability of the group to take specific management actions, based on trends revealed by the monitoring effort. Experiences from other cases attempting to employ active adaptive management suggest that the application of an experimental approach to natural resource management remains difficult to practice, despite a well developed body of theory, primarily because of political issues and institutional cultures (Johnson 1999). This could also explain why we found an apparent contradiction between survey responses indicating Diablo Trust support for the role of the monitoring effort in facilitating the group’s progress to achieve its goals, while at the same time the survey results reveal little confidence that the effort will result in active adaptive management (Table 1).

In this case study, institutional obstacles have been a challenge, as exemplified by a lengthy Environmental Impact Assessment (EIS) process that the group had to undertake to obtain National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) approval by the U.S. Forest Service for implementing management actions on federal lands. The EIS was approved in 2004 following several years of planning, during which time the implementation of collaborative management could be undertaken on lands under private and state ownership. During this time, parts of the initial plan changed, making it difficult throughout the years to create a system that would streamline the monitoring data to inform the 3-part holistic goal due to uncertainty over whether the monitoring data being collected was effectively providing a landscape-wide view of progress towards the 3-part management goal. The IMfoS efforts were meant to address this challenge, but the HEHI also needs to remain flexible to changes in management priorities in order to be a useful tool for adaptive management.

It is also important to clarify that the data presented here constitute an assessment of baseline conditions, not a completion of the full adaptive management cycle, which includes implementation, monitoring, assessment, and adjustment of a previously developed management plan. In the case of the Diablo Trust, stakeholders were hesitant to accept this first data set as an evaluation of outcomes, due largely to skepticism about the quality of available baseline data, the high interannual variability associated with most environmental variables in arid ecosystems, and the fact that many planned management activities have been stalled or stopped over much of the land base, due to delayed planning processes and analysis associated with appeals and other challenges to public land management practices. We expect confidence to grow in subsequent years, as new data will more clearly and persuasively identify trends between management actions and indicators—and between the work of the collaborative and its ecological and socio-economic outcomes.

(5) Cross-scale monitoring under the HEHI. Aggregating indicator points into a single HEHI value masks important information collected at finer scales, highlighting the importance of thoughtful interpretation of monitoring results at multiple levels. This cross-scale evaluation is made relatively simple by the hierarchical and conceptually structured HEHI adopted for the Diablo Trust’s IMfoS monitoring program. In pursuing this approach, we identified a set of equally important monitoring needs related to specific, short-term management efforts. For example, the Diablo Trust has been conducting yearly pasture monitoring for many years, and data are used to adjust grazing numbers and rotations. Clear discussion of different knowledge needs, manifest at various temporal and spatial scales, allowed us to integrate efforts and increase efficiencies. In the case of pasture monitoring, this information drives short-term decisions, and is also included in the HEHI as part of the land use indicators to be evaluated in combination with other ecological and social indicators. These different uses of monitoring data provide continuity across scales, helping to address the challenges posed by the need to act in an integrated manner across multiple scales of management. Focused, project-level monitoring addresses the impacts of particular management efforts or specific hypotheses about system dynamics, while “big picture” or broad- scale monitoring assess the overall effects of multiple management actions on the collaborative’s progress toward its ecological and social goals. In this way, the HEHI offers a logically consistent means of assessing progress towards overall program goals (i.e., the Diablo Trust’s 3-part holistic goal) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The true test of the utility of the HEHI monitoring framework lies in its long-term use to guide the decisions and actions of the collaborative. While we cannot predict this outcome at present, the demonstrated commitment to the on-going implementation of the HEHI from the ranchers, agencies, and engaged citizens of the Diablo Trust, offers a positive indication of the utility of the HEHI as a monitoring tool. It suggests that collaborating individuals and the institutions they represent are likely to accept and act on monitoring outcomes in the future. The willingness to invest in the collaboratively developed framework is particularly encouraging, given disagreements among stakeholders over past uses of monitoring data, a skepticism regarding monitoring, in general, and reluctance within some management agencies to embrace approaches developed outside of their institutional structures. We are also encouraged by how implementation of this framework has already generated self-reflection among stakeholders and a desire to improve on deficiencies. These outcomes are essential to effective adaptive management.

The first iteration of the HEHI allowed the group to engage in mutual learning, and, to some extent, participate in a more passive form of adaptive management. We were successful in developing indicators that adequately address the system characteristics and management objectives of the Diablo Trust, and we collected data for almost all of the indicators, allowing us to gauge their ability to capture the trends of greatest importance to decision makers. Examining management objectives in light of these indicators, in itself, led to deeper deliberation regarding the collaborative’s goals and objectives. In that sense, the efforts resulted not only in the first comprehensive baseline dataset for ecological and social conditions; it also resulted in the refinement of desired ecological and social goals. An important component of the feedback mechanisms in adaptive management is the capacity for self-reflection, and the group demonstrated this by reviewing landscape goals and negotiating how to measure their success.

Perhaps most importantly, the work generated a deeper understanding among ranchers and agencies regarding how they want to work together and share responsibilities in implementing and using the monitoring data in the future. We believe a critical factor in overcoming obstacles during collaboration was the mutual trust developed between the collaborative and our research team, members of which have been involved in independent research efforts on Diablo Trust lands for over a decade. This established relationship has helped set a foundation for linking scientific and local knowledge into the operations of the Diablo Trust. Throughout the indicator selection process and workshops, stakeholders trusted us to develop initial lists of indicators, protocols and benchmarks. We believe this process would have taken much longer if trust had not been previously established.

While the HEHI undoubtedly will undergo further refinement, it represents the first comprehensive examination of the multiple objectives and management actions of one of the longest established collaborative management groups in the western USA. A large proportion of the stakeholders surveyed felt that the HEHI provided a cost-effective approach for evaluating key ecological and social indicators of success, and that it reduced the time and effort associated with conducting redundant or inefficient measurements that do not directly inform management decisions or actions. As Diablo Trust monitoring efforts proceed, the adaptive process of refinement will continue. Multiple iterations of these sampling and analytical approaches will be required, and learning flexibility is necessary for discovering a proper balance between perceived knowledge needs and practical constraints with respect to program cost and sophistication. One indication that the adaptive process is ongoing is the commitment that the agencies and resource users have made to continue supporting collaborative monitoring and data sharing through the IMfoS program.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Evaluating the process and outcomes of collaborative management is necessary not only for evaluating the effectiveness of this approach to resource governance and sustainability, but also for building learning capacities and reflexivity among the various stakeholders of the collaborative itself. In light of recent literature that views collaborative management as a complex social-ecological system (Muñoz-Erickson and others 2007; Innes and Booher 1999), monitoring and reflecting on management outcomes and long-term processes becomes increasingly important to understanding the emerging contexts in which ecological and social changes are taking place. Hence, perhaps the most important outcome from our effort was the Diablo Trust’s success in operationalizing the concept of ecosystem health through a stakeholder-based indicator selection process. The framework proposed helped define what aspects of ecosystem health was important to stakeholders, how they should be measured, and how they are relevant to the collaborative process. In this sense, this framework integrates ecosystem health, sustainability, and the success of collaboration and adaptive management, thus providing a crucial link between process and outcomes that has so far received little attention in the collaborative management literature.

Overall, the HEHI framework, and the participatory process used to develop it for the Diablo Trust context, was successful in meeting monitoring needs of a collaborative. We had the advantage, however, that the Diablo Trust already had a well-developed set of goals, a management plan, and a vague recognition of their monitoring needs, laying out most of the ground-work needed to move directly into the specifics of the monitoring plan. In addition, the group had developed a level of trust and ease of interaction that facilitated progress on difficult issues. Other collaboratives, especially those initiating their process and starting to develop a management plan, may not be able to progress as rapidly, and may benefit from involving all stakeholders early in the indicator selection process, as this will help to clarify the purpose of the monitoring program (Fernández-Giménez and others 2006). In such cases, it is important to allow adequate time for deliberation in the formulation of goals, and the identification and weighing of indicators, to ensure that the monitoring tool is perceived as credible and directly linked to the knowledge and management needs of the various stakeholders involved. Researchers, natural and social scientists alike, can assist this process by providing tools, methods and protocols that allow the integration of multiple sources of knowledge in evaluating the performance of indicators.

References

Aguilar BJ (1999) Applications of ecosystem health for the sustainability of managed systems in Costa Rica. Ecosystem Health 5:1–13

Armitage DR (2005) Adaptive capacity and community-based natural resource management. Environmental Management 35:703–715

Brick P, Snow D, Van de Wetering S (eds) (2001) Across the great divide. explorations in collaborative conservation and the American West. Island Press, Washington, DC

Costanza R (1992) Toward an operational definition of ecosystem health. In: Costanza R, Norton BB, Haskell BJ (eds) Ecosystem health: new goals for pages 251–261. Environmental Management. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA, pp 239–256

Daniels SE, Walker GB (1996) Collaborative learning: improving public deliberation in ecosystem-based management. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 16:71–102

Diablo Trust (1999) Diablo Trust area range management plan and proposed action. Flagstaff, Arizona

Fernández-Giménez M, Aguilar-González B, Muñoz-Erickson TA, Curtin CG (2006) Assessing the adaptive capacity of collaboratively managed rangelands: a test of the concept and comparison of 3 rangeland CBCs. Journal of the Community-Based Collaborative Research Consortium. [online] URL: http://www.cbcrc.org/php-bin/news/showArticle.php?id=75

Fraser EDG, Dougill AJ, Mabee WW, Reed M, McAlpine P (2006) Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. Journal of Environmental Management 78:114–127

Hezri AA, Dovers SR (2006) Sustainability indicators, policy and governance: Issues for ecological economics. Ecological Economics 60:86–99

Innes JE, Booher DE (1999) Consensus building and complex adaptive systems: a framework for evaluating collaborative planning. American Planning Association Journal 65(4):413–423

Johnson BL (1999) Introduction to the special feature: adaptive management–scientifically sound, socially challenged? Ecology and Society 3(1):10

Kenney DS (2000) Arguing about consensus: examining the case against western watershed initiatives and other collaborative groups active in natural resources management. Natural Resources Law Center, University of Colorado School of Law, Boulder, Colorado, USA

Leach WD, Pelkey NW (2001) Making watershed partnerships work: a review of the empirical literature. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management 127(6):378–385

McCloskey M (1996) The skeptic: collaboration has its limits. High Country News, May 13

Moir WH, Block WM (2001) Adaptive management on public lands in the United States: commitment or rhetoric? Environmental Management 28(2):141–148

Moote MA, McClaran MP (1997) Viewpoint: implications of participatory democracy for public land planning. Journal of Range Management 50(5):473–481

Muñoz-Erickson TA, Aguilar-González BJ, Sisk TD, Loeser MR (2006) Assessing the effectiveness of the Holistic Ecosystem Health Indicator (HEHI) as a monitoring tool to assess the adaptive capacity of Community-based Collaboratives. Journal of the Community-Based Collaborative Research Consortium. [online] URL: http://www.cbcrc.org/php-bin/news/showArticle.php?id=77

Muñoz-Erickson TA, Aguilar-González BJ, Sisk TD (2007) Linking ecosystem health indicators and collaborative management: a systematic framework to evaluate ecological and social outcomes. Ecology and Society 12(2):6

Norton BG (2005) Sustainability: a philosophy of adaptive ecosystem management. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Olsson P, Folke C, Berkes F (2004) Adaptive comanagement for building resilience in social-ecological systems. Environmental Management. 34(1):75–90

Rapport DJ (1995) Ecosystem health: exploring the territory. Ecosystem Health 1:5–13

Reed MS, Fraser EDG, Dougill AJ (2006) An adaptive learning process for developing and applying sustainability indicators with local communities. Ecological Economics 59:406–418

Sabatier PA, Focht W, Lubell M, Trachtenberg Z, Vedlitz A, Matlock M (2005) Collaborative approaches to watershed management. In: Sabatier PA, Focht W, Lubell M, Trachtenberg Z, Vedlitz A, Matlock M (eds) Swimming upstream: collaborative approaches to watershed management. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, pp 3–21

Steedman RJ (1994) Ecosystem health as a management goal. Journal of the North American Benthological Society 13(4):605–610

Tilt W, Conley C, James M, Lynn J, Muñoz-Erickson TA, Warren P (2008) Creating successful collaborations in the West: lessons from the field. In: van Riper C III, Cole KL (eds) Proceedings for the eight biennial conference on research on the Colorado Plateau. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona, USA

Wondolleck JM, Yaffee SL (2000) Making collaboration work: lessons from innovation in natural resource management. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA

Yin RK (1992) The case study method as a tool for doing evaluation. Current Sociology 40(1):121–137

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Diablo Trust, and in particular, the Flying M and Bar T Bar Ranches, for their constant support and participation in this study. We would also like to thank Mike Hannemann and Dan Rusell (U. S. Forest Service), Stephen Williams and Kevin Eldrege (A.Z. State Land Department), and Rick Miller (A.Z. Game and Fish Department) for contributing time, data, and personnel to the monitoring field work. Special thanks to the late John Prather, whose expertise in field ecological protocols and GIS analysis was invaluable to this project. Numerous undergraduate and graduate students contributed to this project, including A. Richey, E. Ruther, R. Reider, V. Humphries, A. Cronin, E. Bernstein, L. Taylor, L.Walters, S. Mezulis and undergraduates in the Agroecology Summer Program from Prescott College. This project was funded in part by the Ecological Restoration Institute at Northern Arizona University, the Environmental Protection Agency’s P3 Sustainability Award, the Community-Based Collaborative Research Consortium (CBCRC) at the University of Virginia, and student assistance and in-kind contributions from Prescott College. Writing of this manuscript was made possible through support from the National Science Foundation Integrated Graduate Education and Training (IGERT) in Urban Ecology Program, Grant No. DGE 0504248, and the School of Sustainability, Arizona State University. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding entities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muñoz-Erickson, T.A., Aguilar-González, B., Loeser, M.R.R. et al. A Framework to Evaluate Ecological and Social Outcomes of Collaborative Management: Lessons from Implementation with a Northern Arizona Collaborative Group. Environmental Management 45, 132–144 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-009-9400-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-009-9400-y