Abstract

The current paper aims to analyse the complex array of practices entailed by teams and esports professionals by looking at one of the most peculiar phenomena of the esports field: gaming houses, i.e., “co-operative living arrangement[s] where several players of video games, usually professional esports players, live in the same residence” [1]. Representing one of the first attempts to assess the role of gaming houses as emerging esports spaces based on new forms of playbour and production of and by users, the paper comprises an innovative adaptation of PRISMA protocol for literature and scoping reviews to shed light on how the technological, material, and social elements are enacted through gaming houses’ activities, which mirror the ones entailed by digital platforms. In fact, through the three moves of encoding, aggregating and computing users’ interactions [2], gaming houses (re)produce virtual and analogical goods, translating consumer practices and profoundly influencing the broader esports ecosystem. Finally, by framing themselves as ideal hives for pro players, i.e., a prototypical breeding ground for esports professionals, these structures push for new paradigms of work-life balance and users’ production, thus leading to a further reflection on the nature of play and working practices in our contemporary network society [3].

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The rise of esports professionals [4,5,6] and gaming content producers [7,8,9] has already drawn the attention of social, media and game scholars, which have focused mainly on the spectatorship dimension [10,11,12] and the emergent identities and cultures associated with gaming [13,14,15,16]. On the other hand, labour researchers highlighted the “prosuming” perspective [17, 18], underlining how the gaming industry transforms gamers’ consumption practices into processes of production shared within and without the gaming field. What blossomed in the gaming field eventually spilt over the broader society, as displayed by the spreading of gamification among businesses and institutions [19,20,21,22].

In such a scenario, esports teams (i.e., groups of professional players that gather to participate in competitions and operate better in the economic market) emerged as relevant organisational actors [23, 24]. Evolving from simpler LAN parties’ organisers, these groups of gamers undergo a process of institutionalisation and transformation along trajectories of progressive specialisation [25]. Nowadays, teams usually involve multifaceted activities to increase revenues, like training together and streaming independently; simultaneously, they confront some of the most diffused biases of the field [26] and propose new solutions to the hurdles they encounter [27].

The current paper tries to catch a glimpse over the complex array of practices entailed by teams and esports professionals through their daily grind by looking at one of the most peculiar phenomena of the field: gaming houses, i.e. “co-operative living arrangement[s] where several players of video games, usually professional esports players, live in the same residence” [1]. Depicted as ultimate professionalising tools by many insiders [28], these “houses” offer a privileged empirical ground for assessing how the esports ecosystem adopts new paradigms of work-life balance and users’ production [29,30,31]. Albeit they can respond to different needs [28], these coworking and co-living spaces are the place of continuous refinement of the narratives and identities associated with the figure of the pro players [32]. Moreover, they are also framed as ideal hives to nurture new talents and workspaces for new-fangled professions [33, 34].

Thus, this contribution aims to analyse how gaming houses are composed, administered, and lived. In other words, it will examine how the socio-material matrix [35, 36] embedded in gaming houses influences the houses’ (spatial) ecosystem, which allegedly composes the prototypical breeding ground for an esports professional [37]. Then, the literature review will focus on the material aspects and the social structures inside the houses, but also how these are enacted to narrate a professional(ising) trajectory into which these structures play a crucial role [38, 39]. Finally, the last part will highlight how a deeper understanding of these structures may contribute to the current literature on esports as well as offer insights about the embedding of digital technologies in contemporary societies and (new) working practices.

2 Related Works

While scholars have already tackled either the subjective dimension of esports [40,41,42,43,44] or the sociotechnical innovations brought in by esports teams and professional players in the broader gaming scenario [25, 31, 45,46,47], gaming houses are still an unexplored theme for academia. However, notable exceptions are constituted by the works of Can [37] and Thornham [16]: the former represents an in-depth analysis of the current Turkish esports scene focusing on the role that gaming houses play inside that specific local context, enriched by a reflection on the persistent gender inequality and segregation that these structures seem to reinforce [37]; on the other hand, the latter book by Thornham [16] expands on the issue of gender inside the gaming community by exploring the use of these technologies inside the domestic environments [48, 49], putting the work on the page of current media literature on the theme.

Nonetheless, the latter work brings up a “semantic” problem, as Thornham’s research space shares little to no connection to the professional(ised) venture intended by esports insiders with the term “gaming houses”. By means of opening up a scholarly discussion on these structures, this paper will address this need for clarification by proposing a first definition of gaming houses, which arises through the lay literature on the theme describing their components and functioning.

3 Methodology

Scholarly approaching gaming houses reveals the scarcity of academic literature regarding these structures. Although many authors have devoted their attention to the competitive scene [25, 30, 50], gaming houses have remained a theme only for insiders and fans. This is why this paper, following some promising results obtained through exploratory inquiries into the Internet, proposes to fill the literature gap by addressing the lay knowledge circulating among gaming communities. However, it was necessary to adapt standard literature review procedures to build a scientific point on such an unstructured body of work. The choice was to use the PRISMA protocol for literature and scoping reviews [51], adapting it to unconventional repositories in order to systematically approach this vast but raw knowledge while maintaining academic reliability.

3.1 Inclusion Criteria

The material included had to talk specifically of gaming houses (i.e., shared households inhabited only by pro players); or other structures devoted to gathering and offering a space to professional gamers; or labelling themselves as “gaming” or “team houses”. Consequently, gaming houses were operationally defined as structures, either established by teams or funded by external companies, devoted to hosting pro players temporarily (i.e., bootcamping venues) or permanently (as proper housing solutions) during their playing, training, and living activities. This definition was adopted to distinguish houses from other venues inside the gaming ecosystem (e.g., LAN houses or PC bangs). In addition, the entries chosen for queries reflected the semantic variability found in preliminary searches. Thus, the following keyword combinations were used:

-

game house;

-

gaming house;

-

gaming team house.

3.2 Sources

To fruitfully merge scientific and lay knowledge on gaming houses, the queries were performed on unconventional repositories (accessed through Bing, Google, and YouTube) and then paired with a more common search over the typical academic databases. The scarcity of findings suggested including not only the stricter database Scopus (Elsevier) but also the broader and “messier” Google Scholar, aiming to include even its grey literature and low-tier journals in the review.

To sum up, the following sources have been examined:

-

Microsoft Bing (search engine);

-

Google Search (search engine);

-

YouTube (media platform);

-

Scopus (academic database);

-

Google Scholar (academic and grey literature search engine).

3.3 Disclaimer on Sources

Acknowledging that one of the major perils of using Internet sources could be stepping in their built-in biases and, more precisely, the possibility that the searching algorithm might influence the results, some precautions were adopted to limit an excessive manipulation of the data: two parallel searches were conducted, keeping the same web browser (Microsoft Edge) but changing the search engine from Bing to Google. Moreover, the Google search engine was linked to a new account to counter past search history effects. Except for the hardly avoidable information related to the IP address and the geolocation of the machine (Northeastern Italy), the two engines differed in the language adopted: Bing ran in the default English, whereas Google in the suggested Italian (because of the IP address)Footnote 1.

Moreover, the choice of adding the media site YouTube, even if related to Google Search, was motivated by the large number of videos that emerged in preliminary searches. Indeed, the recognised link between gaming activities and video-sharing platforms like YouTube and Twitch.tv [8, 9, 50] suggested exploring at least one of them: the more extensive database of YouTube and its characteristic of keeping track of videos and comments, a feature lacking in many Twitch channels [53, 54], pushed for its choice.

All searches were carried out over the last week of November 2022, and every result was double-checked and finally consulted during January 2023.

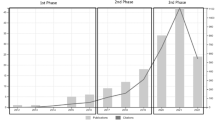

3.4 Search Strategy

Search engines output massive volumes of results (the highest was “around 4.170.000.000 results in 0,47 s”, as reported by Google) that could hardly be filtered. The decision was to limit the search to the first ten pages of results to stem this overwhelming amount while keeping the maximum information possible. This was due to time-constraint reasons and the fact that the records seemed to recur consistently after the first pages, reaching near total repetition (i.e., a full page of already shown records) after the tenth one. The same occurred when searching YouTube, Scopus, and Google Scholar, so the same limit criterion was adopted. However, the single-page output on those sites differed, so the threshold was set to 97 results per source to uniform the searches. Indeed, 97 were the records shown in the first ten pages of (both) search engines.

Moreover, technical issues like broken links, search engines malfunctions, or unretrievable material affected the screening, which in some cases hindered the reach of the expected 97 results for each source. Even though these breakages did not constitute a significant issue, the author added 3 more records from hyperlinks or previously retrieved material.

The total number of reports to be screened was still considerable (n = 1354), and the shambolic nature of search engines’ indexing made it hard to find clusters of relevant results. Nonetheless, after carefully analysing the 195 relevant studies obtained through deduplication and selection processes (see Fig. 1), some significant axes emerged from the raw knowledge, which will now be presented.

4 Findings

A systematic reading of the literature shows how gaming houses represent new opportunities for esports organisations to arrange professional gamers’ activities [28] while transforming teams’ practices into value-laden products [55, 56]. These organisational configurations sallied from Asian territories [32, 38, 57] and rapidly conquered the rest of the world by narrating themselves as crucial professionalising tools for the field [37, 39, 57]. Gaming houses are displayed as places where professional gamers live and play together [58], as well as modern and innovative economic ventures [59,60,61].

Drawing from the extensive knowledge gathered by the gaming community, which has been decidedly more productive on the topic, we can recognise several distinctive elements lying behind the houses scattered around the globe, which will help us understand what is intended by the term “gaming house”. To navigate the data, the paper will first present a guiding definition of gaming houses, albeit still partial and based on lay knowledge, and then continue their analysis through the proposed theoretical lens of platforms’ ecosystemic functioning [2, 62, 63].

4.1 Tracing Gaming Houses’ Roots and Defining Them

The Asian background has heavily influenced gaming houses’ emergence: mangled in densely inhabited and infrastructured zones, the first goal guiding the creation of these structures was offering an affordable housing solution, which seems to remain a major concern for many teams [64]. Even though the current Korean and Chinese scenes have shifted their focus toward economic sustainability and media production, most Asian organisations still aim to find a balance between endless work and leisure gaming screen hours. Indeed, many insiders claim that life inside these households may become exhausting [65, 66]. On the other hand, a more Western model has diffused lately, more focused on the performance-enhancing opportunities that gathering all players and staff in the same place could give. Following a paradigm that imitates other sports disciplines, many American and European teams’ houses emulate sports facilities, starting to criticise the forced co-living for a more flexible “facility model” where gamers gather only for their working (i.e., training) hours. Alongside these two leading and recognisable ideal types, a full assortment of variations for these structures can be found in the different local gaming ecosystems: ranging from the “coerced” model imposed by Riot to the more content-oriented one spreading in the USA, gaming houses seem to maintain operational flexibility that allows them adapting to the diverse needs that gave rise to them.

However, the cornerstones of what defines a gaming house can be summed up as: being a place where (1) professional gamers live together regularly, even if temporarily (i.e., for bootcamps), and (2) they use such spaces for professional gaming (either matches or training); (3) when in use, gaming houses spaces are not accessible by outsiders, except from invited ones or in certain areas (or events). This definition helps discriminate gaming houses from other types of simpler housing solutions adopted by teams [67] and distinguish them from facility-style configurations [68] or other arrangements renting PC stations and other services to (usually amateur) teams and single players [69].

4.2 Gaming Houses as Platformised Environments

Through the literature emerges how gaming houses slowly constructed a general aura of irreplaceability around themselves [57, 70], framing their existence both as a technical and organisational advancement [68, 71] and as an inescapable consequence of esports professionalisation [28, 64]. This central positioning inside the esports ecosystem is obtained through an assemblage of digital, material, and social components, forming these structures’ unique environments [72]. Notably, gaming houses seem to mirror platforms’ ecosystemic functioning [2, 62, 63], inasmuch they frame their services as life-improving and producing better versions of their “users” (i.e., team members) through encoding, aggregating, and computing the practices entailed in their spaces.

The following paragraphs will expand on this utterance by tackling gaming houses’ complex network of components and functions through the theoretical lens provided by Alaimo and colleagues [2, 62]. Paraphrasing Apperley and Jayemane [73], looking at gaming houses through platform studies offers the opportunity to locate them “as the stable object within a complex, unfolding entanglement” of traceable and examinable relations [73]. Approaching the material substrate behind the esports ecosystem through a similar lens will enhance the understanding of these structures as both “standard objects”, routinely dealt with by insiders, and “black boxes”, to be spread over by deconstructing them into their components [73,74,75].

This way, it will become clear how the houses’ constitutive elements concur in accompanying amateur gamers towards professionalism through three “moves”: encoding, aggregating, and computing.

Encode.

Gaming houses are engaged in a framing effort, as they constantly try to depict pro players’ gaming practices as professional [58, 66, 76]. If this can more easily hold for players, houses strive to enlarge their encoding to broader social communities. As they try to loyalise their fanbase with digital goods, like promo codes and sports merchandise [77], houses often employ community-building tactics [61, 78] and even lifestyle models [79, 80] to enrol followers and fans into the crafting of the professional figure of the pro player.

Digital infrastructures emerge as a crucial asset for this move, as most gaming houses nowadays also involve streaming practices carried by their roster members [81, 82], engage in social media to depict their top players as aspirational stars and funnel participation [81, 83], and cooperate with other influential digital firms to broaden their respective communities [55, 56, 61]. These activities are sustained by external infrastructures, like stable and ultra-fast Internet connection [84], and in-house features, like props and architectural renovations [82, 85, 86], that accommodate technologies and furniture like specific lighting [87, 88] and high-end hardware [89].

This way, the new “hardwired” households [90] become not only used but “prodused” by their inhabitants [17, 18] as they transform into fair-like assemblages of amusements and out-screen diversions aimed at the enhancement of their aesthetic qualities [91, 92]. A “streaming turn” also scaffolded by a human capital made of Hollywood creatives, sports psychologists, physiotherapists, marketing consultants, and video makers [59, 77, 79, 80, 92]. These new figures matched the ever-present managers and coaches, more focused on enhancing players’ performance [58, 76, 88, 93]. Thus, this whole new social structure helps teams and players craft contemporary gaming celebrities [7], legitimising gaming and streaming endeavours by offering supporting structures and professionals [58, 94,95,96].

Even though this shift means translating competitive gaming into a tool (or an excuse) to have more content to work with [77, 88, 97], many pro players care about their personal brand as an asset because of the longer, stabler, and higher revenue that streaming practices ensure over esports winnings or salaries, further reinforcing the encoding of their activity as a professional one [9, 37, 38, 57].

Aggregate.

The second move that gaming houses enact is displaying themselves as the elective spatial hubs for hosting the network of actors and objects needed for professional gaming. Indeed, this move frames these structures as an environment housing not only the (freshly defined) professional gamers but also the supporting figures and sustaining materialities, like gyms and relaxation areas [67, 82, 83, 98]. This aggregation process again involves cooperating teams and firms, as they often exchange players (and thus, knowledge and resources) and share partnerships with non-endemic companies [55, 60, 78, 83]. The further inclusion of fans and followers as part of each team community through streaming and social media [50, 58, 81] signals a unique tendency to generate a multilayered and digitally dense ecosystem, inside which gaming houses are positioned, made by the network of these different esports actants [45, 62, 63].

Although the rhetoric of gaming houses tries to detach the figure of the professional gamer from casual ones, the socio-material making of these structures seems undecidedly caught between playing as much as working zones. Although this scenario may challenge the familiar categories that divide play and work [99,100,101], the fundamental support offered by boundary objects [102] helps navigate the assemblage of objects, actors, and spaces devoted to leisure or work efforts, as they are depicted as equally essential in many gaming houses (self-)presentations [94, 96, 103]. Actually, videos and websites cover houses’ playful environments and artefacts, like luxurious pools and old cabinet collections [79, 92, 103], as attractive features for aspiring pros and interested partners [59, 104, 105]. The resulting narrative depicts pro players as enjoying a “totalising” environment [106] where embedded digital infrastructures and physical structures ensnare them between (digital) gaming for professional reasons and playing (analogically and digitally) for leisure. At the same time, this discourse pictures gaming houses as crucial aggregating nodes where all kinds of activities are possible, further framing them as crucial environments for the broader esports ecosystem [28, 39, 64, 65].

Compute.

Finally, esports organisations “compute” all the actions occurring among their walls; that is, they extract value from the spatial nodes represented by gaming houses. Pro players, as well as the complex set of practices entailed in these structures, become valuable leverage for connecting with endemic brands and diverse user bases [55, 107, 108]. Moreover, by presenting themselves as broad-ranging digital companies, the organisations behind the gaming houses expand their influence beyond their industrial and economic boundaries, offering interested actors their spatial structures as reliable intermediaries in the exchange of services and products with followers’ communities and other gaming firms [78, 109,110,111,112].

The appeal of these houses for gaming communities and complementary companies is mainly given by the spatial dimension of their built environment. On the one hand, these structures offer a materiality to collaborating non-endemic firms that position them as unique in a highly dematerialised ecosystem [61, 79, 113], like the one of the gaming industry [45, 114]. On the other hand, the embedding of media and streaming practices, guaranteed by houses’ digital infrastructures, material environment and social capital, allows for targeting the respective media audiences [55]. Indeed, the merging of different user communities and their enrolment into the production processes operated through gaming houses both reflect similar tendencies in the media and platform economy [29] and strengthen the reliability of esports organisations, especially the ones backing these structures [60, 78]. In a reinforcing feedback loop, such an intermediary role assumed by gaming houses further establishes a professional “aura” around competitive gamers (i.e., frames them as professionals), who benefit from these processes of industry expansion and stabilisation: not only do they improve esports professionals’ economic situation, but they raise significantly the social status associated with the pro player figure [5, 24, 32, 56, 83].

Taking this intermediary role to the extreme, some gaming houses even detached from traditional esports organisations, constituting themselves as rentable hubs for both (amateur-ish) gamers and professional teams. Distantiating from the proper houses outlined in this paper, these hardware-ready facilities offer services like fully-equipped recreative areas, cutting-edge bootcamping venues, and hosting gaming-related events [69, 115,116,117,118,119,120]. Thus, even though this latter iteration of gaming structures shows a new direction in the meaning associated with these spaces by leveraging the temporary nature of the usage of these places, they display how the know-how behind gaming houses is being morphed to generate novel (economic) actors in the esports ecosystem. As the esports ecosystem evolves through these spaces, the progressive transformation of bigger gaming houses’ owners into prominent international media companies [78, 109] gives a sense of how meanings and social relations are endlessly negotiated and adapted to the local (material) features behind their constitutive environments.

5 Discussion

The present study constitutes a first attempt to assess gaming houses’ role as platformised spaces [121, 122] that rely on their technological, material, and social elements to embrace gaming’s new forms of playbour [100, 123] and production of and by users [29]. Even though it may constitute a limitation for the study, the inclusion of lay sources in the literature review on gaming houses shed light on how the socio-material assemblage composing these structures is enacted through complex organisational processes, which resemble the ones entailed by digital platforms [2, 62, 63]. This body of secondary data showed how through the three moves of encoding, aggregating and computing users’ interactions [2], gaming houses not only enrol users as produsers [17] but also (re)produce virtual and analogical goods, translating consumer practices and reshaping the gaming industry [18, 29, 45, 72]. Moreover, it emerged how these structures maintain their role as spatialised nodes in the broader esports ecosystem [45, 124] through a set of boundary-setting tactics [125] that establish gaming houses as core actors in an ever-evolving restructuration of the meanings related to the work-play divide (for further discussion on the innovative, yet ambiguous, power of gaming, see [20, 99, 126, 127]). Nevertheless, it must be noted how these substantial differentiating strategies aimed at separating professional players’ activities from amateur(-ish) ones [32, 65, 93, 128] are grounded on the same materialities and digital infrastructures that emancipate gamers from the burden of (traditional) work [64, 129]. Although some insiders and scholars have already warned against the blurring of players’ private and public lives [66, 93, 128, 130,131,132], these shapeshifting qualities allow gaming houses to constantly reposition them and reframe their components along the esports ecosystem and seem to be related to an intrinsic ambiguity belonging to games [133], which is also present in gaming’ analogic forerunners (i.e., traditional sports; [6, 58, 134, 135]) and that may represent the focus of further studies.

6 Conclusion

By adapting the rigorous PRISMA protocol to unconventional lay sources, this paper analysed the complex array of practices and actors forming one of esports’ most peculiar phenomena, i.e., gaming houses. The fan and insiders’ literature showed how these structures frame themselves as ideal hives to nurture cutting-edge workspaces for the new-fangled esports professionals [25, 37, 114]. The paper used the theoretical lens of platforms’ ecosystemic functioning [2, 62, 63] to shed light on how the technological, material, and social elements are enacted through gaming houses’ activities [72]. As a matter of fact, through the three moves of encoding, aggregating and computing users’ interactions, gaming houses embed new forms of playbour [100, 123, 136] and production of and by users [29], as well as constitute themselves as central (material) environments for the esports ecosystem [45, 124, 137]. Finally, the contribution critically engaged with what insiders depict as ultimate professionalising tools to see how their socio-material network led to new paradigms of work-life balance and users’ production [20, 29, 31, 129, 137], which may hint at future further reflections on the ambiguous nature of play and working practices in our contemporary network society [3].

Notes

- 1.

The language used for queries has shown to be one of the “local” factors influencing search engines’ output [52].

References

Gaming house (2022). https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Gaming_house&oldid=1127604193

Alaimo, C., Kallinikos, J.: Computing the everyday: social media as data platforms. Inf. Soc. 33, 175–191 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1318327

Castells, M.: The Rise of the Network Society. Blackwell Publishers, Cambridge (1996)

Hallmann, K., Giel, T.: ESports – Competitive sports or recreational activity? Sport Manage. Rev. 21, 14–20 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.07.011

Jenny, S.E., Manning, R.D., Keiper, M.C., Olrich, T.W.: Virtual(ly) athletes: where esports fit within the definition of “sport.” Quest 69, 1–18 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1144517

Kane, D., Spradley, B.D.: Recognizing ESports as a sport. Sport J. 20, 1–19 (2017)

Johnson, M.R., Carrigan, M., Brock, T.: The imperative to be seen: The moral economy of celebrity video game streaming on Twitch.tv. First Monday (2019)

Tammy Lin, J.-H., Bowman, N., Lin, S.-F., Chen, Y.-S.: Setting the digital stage: defining game streaming as an entertainment experience. Entertain. Comput. 31, 100309 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2019.100309

Taylor, T.L.: Watch Me Play: Twitch and The Rise of Game Live Streaming. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ (2018)

Consalvo, M.: Player one, playing with others virtually: what’s next in game and player studies. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 34, 84–87 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2016.1266682

Hamilton, W.A., Garretson, O., Kerne, A.: Streaming on twitch: fostering participatory communities of play within live mixed media. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1315–1324. ACM, Toronto Ontario Canada (2014). https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557048

Johnson, M.R., Woodcock, J.: The impacts of live streaming and Twitch.tv on the video game industry. Media Cult. Soc. 41, 670–688 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718818363

Arsenault, D.: Super Power, Spoony Bards, and Silverware. MIT Press, Cambridge (2017)

Custodio, A.: Who Are You?: Nintendo’s Game Boy Advance Platform. The MIT Press, Cambridge (2020)

Dovey, J., Kennedy, H.: Game Cultures: Computer Games as New Media. McGraw-Hill Education, UK (2006)

Thornham, H.: Ethnographies of the Videogame: Gender, Narrative and Praxis. Routledge (2016). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315580562

Bruns, A.: Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and Beyond: From Production to Produsage. Peter Lang, New York (2008)

Ritzer, G., Jurgenson, N.: Production, consumption, prosumption: the nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer.’ J. Consum. Cult. 10, 13–36 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540509354673

Burke, B.: Gamify: How Gamification Motivates People to Do Extraordinary Things. Routledge, New York (2014)

Ferrer-Conill, R.: Playbour and the gamification of work: empowerment, exploitation and fun as labour dynamics. In: Bilić, P., Primorac, J., Valtýsson, B. (eds.) Technologies of Labour and the Politics of Contradiction. DVW, pp. 193–210. Springer, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76279-1_11

Jagoda, P.: Experimental Games: Critique, Play, and Design in the Age of Gamification. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (2020). https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226630038.001.0001

Vesa, M., Harviainen, J.T.: Gamification: concepts, consequences, and critiques. J. Manag. Inq. 28, 128–130 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492618790911

Gawrysiak, J., Burton, R., Jenny, S., Williams, D.: Using esports efficiently to enhance and extend brand perceptions – a literature review. Phys. Cult. Sport Stud. Res. 86, 1–14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.2478/pcssr-2020-0008

Richelieu, A.: From sport to ‘sportainment’: the art of creating an added-value brand experience for fans. J. Brand Strateg. 9, 408–422 (2021)

Taylor, T.L.: Raising the Stakes: E-Sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming. MIT Press, Cambridge (2012)

Johry, A., Wallner, G., Bernhaupt, R.: Social gaming patterns during a pandemic crisis: a cross-cultural survey. In: BaalsrudHauge, J., Cardoso, J.C.S., Roque, L., Gonzalez-Calero, P.A. (eds.) Entertainment Computing – ICEC 2021. LNCS, vol. 13056, pp. 139–153. Springer, Cham (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89394-1_11

Bucher, S., Langley, A.: The interplay of reflective and experimental spaces in interrupting and reorienting routine dynamics. Organ. Sci. 27, 594–613 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2015.1041

ESL: Team houses and why they matter. https://web.archive.org/web/20220926170436/ http://www.eslgaming.com:80/article/team-houses-and-why-they-matter-1676. Accessed 09 Jan 2023

Hyysalo, S., Jensen, T.E., Oudshoorn, N. (eds.): The New Production of Users: Changing Innovation Collectives and Involvement Strategies. Routledge, New York (2016). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315648088

Scholz, T.M.: ESports is Business: Management in the World of Competitive Gaming. Springer, New York (2019)

Scholz, T.M.: Deciphering the world of eSports. Int. J. Media Manag. 22, 1–12 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2020.1757808

Zelauskas, A.: Life of an Esports Athlete in a Team House, https://www.hotspawn.com/dota2/news/life-of-an-esports-athletic-in-a-team-house. Accessed 01 Jan 2023

Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Griffiths, M.D., Demetrovics, Z., Király, O.: Career as a professional gamer: gaming motives as predictors of career plans to become a professional eSport player. Front. Psychol. 11, 1866 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01866

Freeman, G., Wohn, D.Y.: Understanding eSports team formation and coordination. Comput. Support. Coop. Work CSCW. 28, 95–126 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-017-9299-4

Barad, K.: Posthumanist performativity: toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 28, 801–831 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

Orlikowski, W.J., Scott, S.V.: Sociomateriality: challenging the separation of technology, work organization. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2, 433–474 (2008). https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520802211644

Can, Ö.: E-sports and Gaming Houses in Turkey: Gender, Labor and Affect (2018)

Bago, J.P.: “SANDATA”: Dispelling the Myth of the Korean Gaming House: What Lessons the Philippine eSports Industry Can Learn From Our Korean Overlords, https://esports.inquirei.net/13920/dispelling-the-myth-of-the-korean-gaming-house-what-lessons-the-philippine-esports-industry-can-learn-from-our-korean-overloads. Accessed 01 Jan 2023

Billy, J.: The Team House Trend. https://dotesports.com/call-of-duty/news/the-team-house-trend-10796. Accessed 30 Dec 2022

Huang, J., Yan, E., Cheung, G., Nagappan, N., Zimmermann, T.: Master maker: understanding gaming skill through practice and habit from gameplay behavior. Top. Cogn. Sci. 9, 437–466 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12251

Ash, J.: Technology, technicity, and emerging practices of temporal sensitivity in videogames. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space. 44, 187–203 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1068/a44171

Rambusch, J., Jakobsson, P., Pargman, D.: Exploring E-sports : a case study of game play in Counter-strike. In: 3rd Digital Games Research Association International Conference: “Situated Play”, DiGRA 2007, Tokyo, 24 September 2007 through 28 September 2007 (2007)

Freeman, G., Wohn, D.Y.: Social Support in eSports: building emotional and esteem support from instrumental support interactions in a highly competitive environment. In: Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, pp. 435–447. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA (2017). https://doi.org/10.1145/3116595.3116635

Scholz, T.M., Stein, V.: Going beyond ambidexterity in the media industry: esports as pioneer of ultradexterity. Int. J. Gaming Comput. Med. Simul. 9(2), 47–62 (2017). https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGCMS.2017040104

Hölzle, K., Kullik, O., Rose, R., Teichert, M.: The digital innovation ecosystem of eSports: a structural perspective. In: Handbook on Digital Business Ecosystems, pp. 582–595. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK (2022)

Kaytoue, M., Silva, A., Cerf, L., Meira, W., Raïssi, C.: Watch me playing, i am a professional: a first study on video game live streaming. In: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on World Wide Web, pp. 1181–1188. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA (2012). https://doi.org/10.1145/2187980.2188259

Burroughs, B., Rama, P.: The eSports trojan horse: twitch and streaming futures. J. Virtual Worlds Res. 8(2), 1–7 (2015). https://doi.org/10.4101/jvwr.v8i2.7176

‘Bo’Ruberg, B., Lark, D.: Livestreaming from the bedroom: performing intimacy through domestic space on Twitch. Converg. Int. J. Res. New Med. Technol. 27(3), 679–695 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856520978324

Harvey, A.: Gender, Age, and Digital Games in the Domestic Context. Routledge, New York (2015). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315757377

Hamari, J., Sjöblom, M.: What is eSports and why do people watch it? Internet Res. 27, 211–232 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0085

Page, M.J., et al.: The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, n71 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Magno, G., Araújo, C.S., Meira Jr., W., Almeida, V.: Stereotypes in Search Engine Results: Understanding The Role of Local and Global Factors. http://arxiv.org/abs/1609.05413 (2016). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1609.05413

Deng, J., Cuadrado, F., Tyson, G., Uhlig, S.: Behind the game: exploring the twitch streaming platform. In: 2015 International Workshop on Network and Systems Support for Games (NetGames), pp. 1–6. IEEE, Zagreb, Croatia (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/NetGames.2015.7382994

Deng, J., Tyson, G., Cuadrado, F., Uhlig, S.: Internet scale user-generated live video streaming: the twitch case. In: Kaafar, M.A., Uhlig, S., Amann, J. (eds.) Passive and Active Measurement. LNCS, vol. 10176, pp. 60–71. Springer, Cham (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54328-4_5

Brand News: Philips Italia entra nel mondo gaming insieme a Mkers, OMD e Fuse. https://www.brand-news.it/brand/tlc-tech/elettronica-di-consumo/philips-italia-entra-nel-mondo-gaming-insieme-a-mkers-omd-e-fuse/. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Forbes BrandVoice: Mercedes-Benz e gli eSports: una sinergia radicata nel passato e rivolta al futuro. https://forbes.it/2021/12/21/mercedes-benz-e-gli-esports-una-sinergia-radicata-nel-passato-e-rivolta-al-futuro/. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Gaming Houses: The Esports Dream or Nightmare?|OverExplained. (2019)

Hood, V.: Life inside a pro-esports team house with Fnatic: streaming, training and burritos. https://www.techradar.com/news/life-inside-a-pro-esports-team-house-with-fnatic-streaming-training-and-burritos. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

Amin, J.: NRG Esports reveals its content house, the NRG Castle|Esportz Network. https://www.esportznetwork.com/nrg-esports-reveals-its-content-house-the-nrg-castle/. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

DBusiness Daily News: Detroit’s Rocket Mortgage Sponsors Esports Online Gaming Competition, Builds 100 Thieves Team House in California. https://www.dbusiness.com/daily-news/detroits-rocket-mortgage-sponsors-esports-online-gaming-competition-builds-100-thieves-team-house-in-california/. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

Samsung Newsroom Italia: Samsung annuncia la nascita dell’eSport Palace un luogo unico nel suo genere in Italia e residenza dei Samsung Morning Stars. https://news.samsung.com/it/samsung-annuncia-la-nascita-dellesport-palace-un-luogo-nel-suo-genere-in-italia-e-residenza-dei-samsung-morning-stars. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

Alaimo, C., Kallinikos, J., Valderrama, E.: Platforms as service ecosystems: lessons from social media. J. Inf. Technol. 35, 25–48 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/0268396219881462

Kapoor, K., ZiaeeBigdeli, A., Dwivedi, Y.K., Schroeder, A., Beltagui, A., Baines, T.: A socio-technical view of platform ecosystems: systematic review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 128, 94–108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.01.060

workaccno33: Gaming Houses. Why? https://www.reddit.com/r/leagueoflegends/comments/1s5jpi/gaming_houses_why/. Accessed 01 Jan 2023

GOOD LUCK HAVE FUN: Life in an esport gaming house with Schlinks, https://www.timeslive.co.za/sport/2017-11-27-life-in-an-esport-gaming-house-with-schlinks/. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

Izento: CLG Biofrost talks buying a house, work-life separation, and the double-edged sword of gaming houses. https://www.invenglobal.com/articles/8493/clg-biofrost-talks-buying-a-house-work-life-separation-and-the-double-edged-sword-of-gaming-houses. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

Retegno, P.: Dentro la Gaming House del Team Forge. https://www.redbull.com/it-it/esport-dentro-la-gaming-house-del-team-forge. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

Byrne, L.: The changing face of gaming houses and esports training facilities. https://esports-news.co.uk/2019/01/16/gaming-houses-esports-facilities/. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

MOBA Milano - Gaming House & eSports Cafè. (2017)

AFP: Inside a gaming house: How an elite eSports team hones its skills under the same roof. https://scroll.in/field/912364/inside-a-gaming-house-how-an-elite-esports-team-hones-its-skills-under-the-same-roof. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

Vivere in una “gaming house”, la nuova frontiera degli eSport. (2019)

Franzò, A.: STS Invaders: gaming as an emerging theme for science and technology studies tecnoscienza. Ital. J. Sci. Technol. Stud. 14, 155–170 (2023)

Apperley, T.H., Jayemane, D.: Game studies’ material turn. Westminst. Papers Commun. Cult. 9(1), 5 (2012). https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.145

Montfort, N., Bogost, I.: Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. The MIT Press, Cambridge (2009)

Montfort, N., Consalvo, M.: The Dreamcast, console of the avant-garde. Loading. J. Can. Game Stud. Assoc. 6, 82–99 (2012)

Carmone, A.: Mercedes e Mkers aprono a Roma la “palestra” per i gamers, https://it.motor1.com/news/546560/merceds-mkers-gaming-house-rome/. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

Touring: The MOST EXPENSIVE Gaming Facility In The World! TSM’s Esports Performance Center (2022)

QLASH: QLASH. https://qlash.gg/. Accessed 09 Jan 2023

We Built the BEST Gaming Facility in the World! (MILLION DOLLAR TOUR) (2020)

ADC Group: Stardust lancia Dsyre, la nuova gaming house italiana. Al Museo della Permanente di Milano esposto l’NFT Stardust. https://www.adcgroup.it/e20-express/news/industry/industry/stardust-lancia-dsyre-la-nouva-gaming-house-italiana-al-museo-della-permanente-di-milano-ssposto-linft-dedicato.html/. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

Di Donfrancesco, G.: Abbiamo visitato la gaming house dei Mkers a Roma, https://it.mashable.com/6649/come-e-gaming-house-mkers-roma. Accessed 01 Jan 2023

The MOST LUXURIOUS GAMING FACILITY in INDIA | First Glimpse at S8UL 2.0 ONE MILLION $ FACILITY (2021)

FIRST LOOK AT T1’S NEW GAMING FACILITY IN GANGNAM (English Tour). (2021)

TheFuriees: Origen’s gaming house. www.reddit.com/r/leagueoflegends/comments/2srksn/origens_gaming_house/. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

GamingLyfe.com: The Swifty Gaming House Gets an Upgrade! https://gaminglyfe.com/the-swifty-gaming-house-gets-an-upgrade/. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

Santin, F.: I vantaggi di vivere in una gaming house per giocatori esport? Ce li svela FaZe Swagg! https://www.everyeye.it/notizie/vantaggi-vivere-gaming-house-giocatori-esport-ce-svela-faze-swagg-587638.html. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

ETERNAL FIRE GAMING HOUSE VLOG (2022)

TOURING THE BEST GAMING HOUSE IN ESPORTS! (2019)

Team Secret LoL EXCLUSIVE GAMING HOUSE Sneak Peek (2020)

Taylor, N.: Hardwired. In: Sharma, S., Singh, R. (eds.) Re-Understanding Media, pp. 51–67. Duke University Press, Durham (2022)

TOUR DELLA QLASH HOUSE! GAMING HOUSE PIU’ GRANDE D’EUROPA?! (2019)

NRG’s New $10,000,000 Gaming Fantasy Factory | NRG Castle Full Facility Tour. (2020)

Sledge, B.: Excel Esports’ new BBC documentary shows the struggles of living in a gaming house. https://www.theloadout.com/excel-esports/gaming-house-struggles. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Revealing The New $30,000,000 FaZe House (2020)

The BEST $1,000,000 Gaming House Tour in Vegas | TSM Rainbow Six Siege (2021)

TOURING THE BEST CONTENT HOUSE IN GAMING ft. CouRage, Valkyrae, Nadeshot & BrookeAB. (2020)

DSYRE: DSYRE | Esports, Streetwear, Intrattenimento. https://dsyre.com/. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Khám phá NRG GAMing House TRIỆU ĐÔ (2022)

Kerr, A.: The Business and Culture of Digital Games: Gamework/Gameplay. SAGE Publications Ltd., London (2006). https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446211410

Kücklich, J.: Precarious Playbour: Modders and the Digital Games Industry. Fibreculture J. (2005). https://five.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-025-precarious-playbour-modders-and-the-digital-games-industry/

Törhönen, M., Hassan, L., Sjöblom, M., Hamari, J.: Play, Playbour or Labour? The Relationships between Perception of Occupational Activity and Outcomes among Streamers and YouTubers (2019)

Star, S.L., Griesemer, J.R.: Institutional ecology, `Translations’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology, 1907–39. Soc. Stud. Sci. 19, 387–420 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

Marsh, J.: Botez Sisters, JustAMinx, And CodeMiko Unveil Brand-New Envy House. https://www.ggrecon.com/articles/botez-sisters-justaminx-and-codemiko-unveil-brand-new-envy-house/. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

Di Felice, G.L.: Mkers Gaming House: la casa dei Pro Player e il simulatore da 40.000 euro - HDmotori.it. https://www.hdmotori.it/mercedes-benz/articoli/n546855/mercedes-benz-mkers-gaming-house-esport/. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

LA GAMING HOUSE DE TEAM HERETICS - ESPECIAL 1 MILLÓN (2019)

Goffman, E.: Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Anchor Books, Garden City (1961)

ENCE: ENCE Gaming House. https://www.ence.gg/article/ence-gaming-house. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Team Liquid’s NEW EU Alienware Training Facility! (2020)

100 Thieves: 100 Thieves. https://100thieves.com/. Accessed 09 Jan 2023

Macko Esports: Macko Esports - The org #DrawnToDare. https://www.mackoesports.com/. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Mkers: Mkers. https://shop.mkers.gg/. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

NRG: NRG Esports|Home. https://www.nrg.gg/. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Schiavella, U.: Mkers Gaming House Powered by Mercedes-Benz, https://www.gazzetta.it/Auto/10-11-2021/mkers-gaming-house-powered-by-mercedes-benz-4202326729847.shtml. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

Johnson, M.R., Woodcock, J.: Work, Play, and Precariousness: An Overview of the Labour Ecosystem of eSports. Media Cult. Soc. 43, 1449–1465 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437211011555

1337Camp: 1337 Bootcamp/Gaming House. https://1337.camp/en. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

East, T.: Dentro il Red Bull Gaming Sphere di Londra. https://www.redbull.com/it-it/red-bull-gaming-sphere. Accessed 03 Jan 2023

Esport Palace. https://esportpalace.it/. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

The GameHouse. https://www.coexistgaming.com/gamehouse. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

Ring, O.: Step inside the OG team house. https://www.redbull.com/int-en/og-team-house-tour-video-and-q-and-a-red-bull-esports. Accessed 01 Jan 2023

The Bug Game House: The Bug Game House. https://www.thebuggamehouse.com/. Accessed 10 Jan 2023

Nieborg, D., Poell, T.: The Platformization of Making Media. In: Deuze, M., Prenger, M. (eds.) Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions, pp. 85–96. Amsterdam University Press (2019). https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048540150.006

Poell, T., Nieborg, D.B., Duffy, B.E.: Platforms and Cultural Production. John Wiley & Sons, London (2021)

Goggin, J.: Playbour, farming and leisure. Ephemera 11, 357–368 (2011)

Yström, A., Agogué, M.: Exploring practices in collaborative innovation: unpacking dynamics, relations, and enactment in in-between spaces. Creat. Innov. Manag. 29, 141–145 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12360

de Certeau, M.: The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press, Berkeley (1984)

Consalvo, M.: Kaceytron and Transgressive Play on Twitch.tv. In: Jørgensen, K., Karlsen, F. (eds.) Transgression in Games and Play, pp. 83–98. The MIT Press (2019). https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11550.003.0009

Taylor, N.T.: Now you’re playing with audience power: the work of watching games. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 33, 293–307 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2016.1215481

Jacobs, H.: Here’s what life is like in the cramped “gaming house” where 5 guys live together and earn amazing money by playing video games. https://www.businessinsider.com/inside-team-liquids-league-of-legends-gaming-house-2015-4. Accessed 01 Jan 2023

Pedersen, V.B., Lewis, S.: Flexible friends? Flexible working time arrangements, blurred work-life boundaries and friendship. Work Employ Soc. 26, 464–480 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012438571

Andrejevic, M.: The work of watching one another: lateral surveillance, risk, and governance. Surveill. Soc. 2, 479–497 (2004)

Duffy, B.E.: The romance of work: Gender and aspirational labour in the digital culture industries. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 19, 441–457 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877915572186

Stanton: The secret to eSports athletes’ success? Lots -- and lots -- of practice, https://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/35343574. Accessed 30 Dec 2023

Sutton-Smith, B.: The Ambiguity of Play. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (1997)

Red Bull Team: Erena è il paradiso del simracing. https://www.redbull.com/it-it/gaming-house-erena. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

Sacco, D.: exceL Esports open LoL training facility at Twickenham Stadium & explain why they’re leaving their gaming house behind. https://esports-news.co.uk/2019/01/05/excel-training-facility-twickenham-stadium/. Accessed 02 Jan 2023

Taylor, N., Bergstrom, K., Jenson, J., De Castell, S.: Alienated playbour: relations of production in EVE online. Games Cult. 10, 365–388 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412014565507

Johnson, M.R., Woodcock, J.: Work, play, and precariousness: an overview of the labour ecosystem of esports. Media Cult. Soc. 43, 1449–1465 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437211011555

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

franzó, a., Bruni, A. (2023). Gamers’ Eden: The Functioning and Role of Gaming Houses Inside the Esports Ecosystem. In: da Silva, H.P., Cipresso, P. (eds) Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications. CHIRA 2023. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1997. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49368-3_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-49368-3_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-49367-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-49368-3

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)