Abstract

This paper empirically investigates the impact of finance and institutions on the economic growth of the Western Balkan economies – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia – using a panel data analysis covering 2000–2020. While individually, neither finance nor institutions significantly impact economic growth, they increase the sample countries’ GDP when the two interact. Furthermore, the results suggest that the finance-growth relationship is non-linear, with a positive impact having a threshold. This relationship also depends on the sample’s institutional development (and vice versa). Similarly, this relationship depends on the proxy used, and hence, we need to be careful when making conclusions.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Financial development

- Institutional development

- Economic growth

- Emerging countries

- Transition economies

- Western Balkans

1 Introduction

The economic growth of any country is affected by several factors such as government spending, human capital, monetary and fiscal stability, financial sector, and institutional development. Studies show that their impact may depend on internal conditions. Since Schumpeter wrote his seminal work in 1912, the debate on the importance of financial development is not fading (Schumpeter 1912). Although financial development is among the most influential factors, its role is continuously challenged. For instance, Ali et al. (2020) and Rousseau and Wachtel (2011) find that this finance-growth relationship has diminished in recent years. Besides, different proxies sometimes provide conflicting results. The efficiency of traditional measures of financial development (private credit, liquid liabilities, broad money, etc.) is also questioned. The financial sector is a dynamic and complex system. Thus, its measures need continuous updates to reflect their true nature. This is why Svirydzenka (2016) developed alternative and more comprehensive measures of financial development.

Furthermore, as the finance-growth relationship is fading and knowing that other factors may influence this relationship, researchers are shifting their focus to institutional quality and its impact on growth directly and indirectly via its effects on financial development. Studies show that political stability, the rule of law, corruption, property rights, and government efficiency – among other institutional development proxies – affect this relationship (Anayiotos and Toroyan 2009; Gani and Ngassam 2008; Law and Habibullah 2009; Hakimi and Hamdi 2017; Slesman et al. 2019). Nevertheless, all these variables and their relationships with growth may significantly depend on the overall conditions and development of sample countries.

The existing literature, except few studies, focuses primarily on developed economies, ignoring less developed ones, particularly transition economies (TE) such as those from the Western Balkans (WB). These countries differ in many dimensions and go through social, political, economic, and institutional changes that affect their overall performance. While significant reforms have been introduced in the WB countries, they are far from reaching the EU standards. These countries are among the most corrupt countries globally, where the rule of law is the lowest (Popovic et al. 2020). Such a business environment is not conducive to economic growth (Smolo 2021a).

In short, WB countries need institutions (financial and otherwise) that would support and promote economic growth. This study addresses the finance-growth nexus using the Western Balkans as the sample, whose financial and institutional developments are similar. The main objective of this study is to determine the effect of financial and institutional development on economic growth within the sample mentioned above. The WB countries are important for several reasons. First, they occupy an important geopolitical position. Given the ongoing crisis in Ukraine and political instability in the region, these countries represent a socio-political threat to the EU and the wider region. Effective institutions and growing economies of these countries would benefit not only the WB region but also the EU. Second, while aspiring to become members of the EU, failing to meet the EU standards may undermine the integrity and stability of the EU. Finally, by evaluating the financial and institutional developments of these countries, the study will evaluate the various programs implemented in these sectors by the EU and other international financial institutions. The international community, in general, played and still plays a vital role in regional development.

The rest of the study is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a literature review; Sect. 3 describes the data and methodology used; Sect. 4 analyses empirical results; and Sect. 5 offers concluding observations.

2 Literature Review and Hypothesis Setting

As pointed out in the introduction, the finance-growth relationship attracts a significant amount of research. Schumpeter (1912); Robinson (1952); Goldsmith (1969); Shaw (1973); and Lucas (1988) provide a theoretical foundation that led to an expansion of the literature on the topic. Although the pioneers of the issue pointed to a positive relationship between finance and growth, the literature reveals conflicting results.

Many of those studies align with the view advocated by the authors mentioned above. For instance, one of the earliest studies on the topic was carried out by Levine (1997 2003). He found that financial development – proxied by the banking size and the stock market liquidity – leads to economic growth. This view is the most prevailing one in the literature and is known as the ‘supply-leading hypothesis’ (Ahmed and Ansari 1998; An et al. 2020; Beck et al. 2000, 2014; Bittencourt 2012; King and Levine 1993; Levine et al. 2000; Rajan and Zingales 1998; Seetanah et al. 2009). However, once a certain threshold is reached, this positive impact turns negative, making this relationship non-linear (Law and Singh 2014; Prochniak and Wasiak 2016; Swamy and Dharani 2019a).

While the importance of finance for economic growth is evident, the results show that its effect depends on financial development proxy, sample countries, study period, methodology used, income level, and type of economy (An et al. 2020; Barajas et al. 2013; Carré and L’œillet 2018; Hsueh et al. 2013; Nyasha and Odhiambo 2018; Yang 2019). Consequently, Luintel and Khan (1999), Khan (2001), and Andersen and Tarp (2003), among others, found a negative impact of finance on economic growth. Still, several studies found more than one relationship between finance and growth (Hassan et al. 2011; Hsueh et al. 2013; Marques et al. 2013; Smolo 2020), while others found no significant impact of finance on growth (Lucas 1988; Shan and Morris 2002; Nyasha and Odhiambo 2015; Smolo 2021b).

Besides, many studies indicate that legal system, education, investment, trade openness, and institutional development – among others – have a significant impact on financial development directly (Bittencourt 2012; Levine et al. 2000; Seetanah et al. 2009). As a result, they would impact growth through their impact on finance. Hence, the researchers focused on other factors, such as institutional development proxied by several measures. For instance, among the crucial factors that affect the finance-growth relationship are political stability, property rights, the rule of law, accounting standards, control of corruption, and government efficiency (Anayiotos and Toroyan 2009; Demetriades and Fielding 2012; Gani and Ngassam 2008; Girma and Shortland 2007; Law and Azman-Saini 2008; Slesman et al. 2019). In other words, the positive impact of finance on growth is subject to a certain level of institutional development/quality (Minea and Villieu 2010; Djeri 2020; Slesman et al. 2019; Kutan et al. 2017). In addition, government efficiency and democracy lead to institutional efficiency and eventually economic growth in Pakistan (Murtaza and Faridi 2016) and economic growth of sub-Saharan African countries (Sani et al. 2019).

All in all, while the discussion over the finance-growth relationship is exhaustive, the results are unconvincing. The interconnectedness of social, economic, and political institutions sheds some light on this complex issue. In particular, there is a reasonable doubt that institutional development has a direct and indirect effect on economic growth and finance-growth relationship, respectively. As a result, this tripartite relationship – institutions-finance-growth – lacks proper attention and requires further investigation. Thus, this study is trying to address it using the Western Balkan countries, which are considered transition economies. The study will provide new insights on the topic and offer valuable policy recommendations while adding to the existing and growing literature.

In short, based on existing literature, this study will test the following hypotheses:

H1: Financial development affects economic growth positively.

H2: The impact of financial development on economic growth is non-linear.

H3: The effect of financial development on economic growth depends on institutions.

H4: The finance-growth nexus depends on proxies used for financial development indicators.

3 Model Specification, Methodology, and Data

3.1 Data and Sample Selection

To investigate the relationship between financial and institutional development on one side and economic growth on the other, this study uses annual-level data for the Western Balkan countries – Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia.Footnote 1 These economies are relatively small and open, transitioning from a planned or command to a market economy.

In line with the existing literature, our dependent variable is the GDP growth rate (GDP) as a measure of economic growth (Swamy and Dharani 2019b). For robustness tests, we are using the real per capita GDP growth rate (GDPp) instead (Kutan et al. 2017; Swamy and Dharani 2019b). When it comes to financial development variables, previous studies used several proxies. Some studies use a ratio of credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP (PR) to capture the efficiency of funds channeling to the private sector (Al-Malkawi and Abdullah 2011; Levine 1997; Smolo 2020). Others use a ratio of liquid liabilities to GDP (LL) to capture the financial sector size and depth (King and Levine 1993; Levine 1997; Compton and Giedeman 2011; Law and Singh 2014; Smolo 2020). Due to missing data for these proxies, this study relies on domestic credit (DC) to the private sector by banks and broad money (BM), both as a percentage of GDP.Footnote 2

Besides, Svirydzenka (2016) argues that these traditional variables do not reflect the multifaceted nature of financial development. Consequently, apart from the two proxies for financial development mentioned above, this study explores the financial development index suggested by Svirydzenka. This index considers the depth, accessibility, and efficiency of financial institutions and markets jointly.Footnote 3 Furthermore, as several studies find a non-linear relationship between finance and growth, this study also uses squared terms of these financial variables (Rousseau and Wachtel 2011; Breitenlechner et al. 2015; Haini 2020).

Similarly, institutional development is also a complex, multidimensional concept as scholars used various indicators as its proxies. This study relies on two different measures. The first one is the Heritage Foundation’s institutional development (overall score). The second is the institutional quality index constructed based on six World Bank database’s World Governance Indicators (WGI) indicators. These indicators are control of corruption, political stability, the rule of law, regulatory quality, voice and accountability, and government effectiveness developed by Kaufmann et al. (2010). However, instead of examining each indicator separately or jointly, we construct the institutional quality index using the principal component analysis (PCA). Using each indicator separately may not provide the overall quality of institutions as it is a complex phenomenon. At the same time, using all these indicators simultaneously may not be appropriate as they are highly correlated (Globerman and Shapiro 2002; Buchanan et al. 2012). Hence, using factor analysis and following Globerman and Shapiro (2002) and Buchanan et al. (2012), we construct the institutional quality index by extracting the first principal component of those six institutional quality indicators. In addition, to determine the indirect impact of institutions on growth through financial development, the study employs interaction terms of each financial development indicator with institutional development proxies (Haini 2020).

Furthermore, besides finance and institutions, other factors also influence economic growth. Thus, the study uses several control variables commonly used in the literature on the topic. These control variables are: GCF, the gross capital formation (% GDP) reflecting the overall economic development of a country; TO, trade openness is measured by the sum of exports and imports of goods and services (% GDP) representing the significance of international trade on economic activities; FCE, final consumption expenditure (% GDP) as a proxy for investment in physical capital; LF, measured by total labor force and represent the human capital development; and INF, inflation rate measured by GDP deflator (annual %) indicating macroeconomic and business environment (in)stability (Beck et al. 2014; Bist 2018; Ibrahim et al. 2017; Sabir et al. 2019; Swamy and Dharani 2019b). Table 1 provides summary statistics of all variables used in model estimations, while Table 4 (see the Appendix) provides the correlation matrix between these variables.

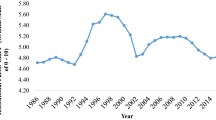

All data are sourced from World Development Indicators (World Bank), World Governance Indicators (World Bank), the Heritage Foundation, and the IMF Financial Development Index Database (Svirydzenka 2016) and cover the 2000–2020 period. The study focuses on this period because the majority of the Western Balkan countries went through turbulent times during the’90s, and it took some years for these countries to get their economies back on track. Including observations from earlier periods might affect relationships that focus on this study.

3.2 Models and Method Used

The literature is overwhelmed with numerous techniques, indicators, and samples used to investigate the finance-growth nexus. Consequently, previous studies led to mixed results and different conclusions. The majority of studies that used panel data applied models such as fixed (FE) and random effect (RE) or least square dummy variable (LSDV), assuming homogeneity of impact across countries. Studies also used the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation method for dynamic panel data considering it superior to other methods. However, the GMM method is applicable only when we have many cross-section units (i.e., long N) and a short time period (T). Our sample consists of only five countries (i.e., a short N) and relatively long period (T), so we cannot rely on this technique.

Given relative similarities between the sample countries, this study relies on RE and FE methods to assess the impact of financial development and institutional quality on economic growth using the following dynamic panel data model (Agbloyor et al. 2016; Compton and Giedeman 2011):

where for country i (the cross-sectional dimension) at time t (the time dimension), GDPit is the log of annual GDP growth rate, GDPit−1 is the lagged value, FDit is a measure of financial development, IDit is a measure of institutional development, Xit is a vector of all control variables; µi is a country-specific effect, ηt is a time-specific effect, and εit is a random error term that captures all other variables.

As pointed out earlier, there is potential non-linearity in the finance-growth nexus. Hence, we will test this using square terms of financial development indicators as illustrated in the following model:

where \(FD_{it}^{2}\) represents the square term of our financial development measures.

Finally, to test whether the impact of financial development depends on the level of institutional development, we introduce an interaction term to Eq. (1) as presented in Eq. (3) below. These interaction terms allow us to distinguish the direct and indirect impacts of financial and institutional development on growth. As suggested by Brambor et al. (2006), we include all relevant terms in the interaction model specification as follows:

where, FDit × IDit represents the interaction variable. Other terms are as defined earlier.

4 Empirical Results and Discussion

Table 2 presents the estimated results for the linear model based on Eq. (1). This table tests our first hypothesis (H1) whether finance contributes to economic growth. While RE estimations indicate a significantly negative impact of financial development on economic growth, we cannot rely on them as the Hausman test supports FE results. The results show that domestic credit (DC) and broad money (BM) have no significant impact on economic growth except in model (8), which indicates a significantly negative effect of BM on economic growth. These results might be due to the transitional nature of these countries and their low levels of financial market development. All these contribute to the overall instability of economies that could consequently make financial development ineffective. In brief, based on the results, we cannot confirm (H1).

Similarly, institutional development proxies have an insignificant impact on economic growth. It seems that these institutions are not developed enough to significantly impact growth as is expected based on the theoretical underpinnings. This is in contrast to previous studies that showed a significant impact of ID on growth Singh et al. (2009), Nguyen et al. (2018), and Kutan et al. (2017). Similar conclusions are reported by Rousseau and Wachtel (2011).

The results indicate that the lagged dependent variable (GDPt−1) and final consumption expenditure (FCE) have significantly reduced economic growth when it comes to controlling variables. At the same time, trade openness (TO), inflation (INF), and labor force (LF) have a significantly positive impact on growth in most model specifications. Finally, gross capital formation (GCF) is insignificant in all models.

Results based on Eq. (2) that test the possible non-linear relationship between finance and growth (H2) are presented in Panel A of Table 3.Footnote 4 A non-linear relationship is confirmed in two models, (1) and (2), when used in combination with an institutional development proxy sourced from the Heritage Foundation. The results now indicate that financial development contributes significantly to these countries’ economic growth up to a certain point when it turns out to decrease it. In other words, there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between finance and growth. These results align with those reported by Swamy and Dharani (2019b), Law and Singh (2014), and Prochniak and Wasiak (2016). Regardless of these changes, institutional development still has an insignificant impact on economic growth.

Although the individual impact of institutional development is not evident so far, its impact might be strengthened via interaction with financial development proxies. To check whether the effect of financial development depends on institutional development (and vice versa), we introduce the interaction term in Panel B of Table 3. These results are based on our Eq. (3), which investigates whether finance’s impact on growth depends on institutions (H3). In contrast to the results reported in Table 2, the interaction models in Panel B of Table 3 indicate the positive impact of financial and institutional development proxies on economic growth. The interaction terms are also significant but with the negative signs landing support to H3. The results are in contrast to those reported by Minea and Villieu (2010), Djeri (2020), Slesman et al. (2019), and Smolo (2021a). All other control variables are in line with previously reported results.

Earlier, we detected a non-linear relationship between financial development and economic growth (Panel A). We also confirmed an indirect impact of financial development on economic growth via institutional development and vice versa (Panel B). The study goes a step forward and investigates non-linear relationships together with interaction terms. These results are presented in Panel C of Table 3. The earlier results are confirmed, i.e., there is a positive impact of both financial development and institutional development on economic growth with a negative impact of their interaction terms. In line with the results from Panel A, these results also confirm an inverted U-shaped relationship between financial development and economic growth.

As for robustness tests, we run the exact estimations using the real per capita GDP growth rate (GDPp). The main results of the robustness tests are reported in Appendix 1 (see Table 5). The results remain similar to the results from Table 3. Along with all the above estimations, the study also runs additional models using the financial development indices suggested by Svirydzenka. In contrast to the results reported earlier using domestic credit and broad money, these proxies provided mixed results. These results, however, should not be taken for granted as our data are not complete. Still, these findings suggest that the finance-growth nexus depends on financial development proxies used (Fernandez and Galetovic 1994; De Gregorio and Guidotti 1995; Luintel and Khan 1999; Ram 1999; Naceur and Ghazouani 2007; Favara 2003; Hsueh et al. 2013; Carré and L’œillet 2018; Nyasha and Odhiambo 2018). While limited in nature, these findings support the idea that the finance-institutions-growth nexus depends on the interaction of financial and institutional development within sample countries. Hence, we found support for our H4 hypothesis.

Finally, it is essential to note that our results are robust to different combinations of two dependent and two institutional development proxies. These results are not reported but are available upon a reasonable request.

5 Conclusion

The study revisits the finance-growth relationship within the Western Balkan countries, taking into account institutional development. Our results reveal that the linear impact of either financial or institutional development on economic growth is insignificant. The results based on non-linear estimations point to an inverted U-shaped relationship between finance and growth. However, no impact of institutions on growth is detected again. Once interaction terms between financial and institutional proxies enter equations, all terms become positive. The insignificance of financial and institutional proxies individually could be attributed to their underdevelopment. Hence, once they are joined together, their significance comes to the surface.

All in all, our main and robustness results indicate that the impact of finance on growth is positive and non-linear. Similarly, institutional development only plays a positive role in growth when interacting with financial development proxies. Both finance and institutions in these countries are not developed enough to significantly impact economic growth. Based on the results from this study, the policymakers should focus on developing both to foster further economic development of the sample countries. The results, nevertheless, should be viewed with a cation as different proxies may lead to different results. Hence, further analysis is needed to support these findings.

Notes

- 1.

Although Croatia belongs to the Western Balkans, we excluded it from the sample as it joined the EU on 1 July 2013. On the other hand, there are sufficient data for Kosovo and thus we excluded Kosovo from the study as well.

- 2.

The full data for PC and LL are not available for all countries. For instance, these data are not available for Serbia.

- 3.

These results using financial development proxies suggested by Svirydzenka are not reported in this paper. We will only briefly discuss some findings towards the end of the study. One of the reasons for not including them in the main discussion is that this index is not available for Montenegro. As such, the results may not be directly comparable with other results where the data are available.

- 4.

To conserve the space, we are providing results for the main variables only. The impact of control variables remains relatively the same under these specifications. The full results, however, are available upon a request from the author.

References

Agbloyor, E.K., Gyeke-Dako, A., Kuipo, R., Abor, J.Y.: Foreign direct investment and economic growth in SSA: the role of institutions. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 58(5), 479–497 (2016). https://doi.org/10/ghrkfz

Ahmed, S.M., Ansari, M.I.: Financial sector development and economic growth: the South-Asian experience. J. Asian Econ. 9(3), 503–517 (1998)

Ali, M., Ibrahim, M.H., Shah, M.E.: Impact of non-intermediation activities of banks on economic growth and volatility: an evidence from OIC. Singapore Econ. Rev., 1–16 (2020). https://doi.org/10/ghr5zk

Al-Malkawi, H.-A., Abdullah, N.: Finance-growth nexus: evidence from a panel of MENA countries. Int. Res. J. Financ. Econ. 63, 129–139 (2011)

An, H., Zou, Q., Kargbo, M.: Impact of financial development on economic growth: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Aust. Econ. Pap. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8454.12201

Anayiotos, G.C., Toroyan, H.: Institutional factors and financial sector development: evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. IMF Working Papers 09(258), 1 (2009). https://doi.org/10/ghsb4f

Andersen, T.B., Tarp, F.: Financial liberalization, financial development and economic growth in LDCs. J. Int. Dev. 15(2), 189–209 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.971

Barajas, A., Chami, R., Yousefi, S.R.: The Finance and Growth Nexus Re-Examined: Do All Countries Benefit Equally? IMF Working Paper No. 13/130. International Monetary Fund (2013)

Beck, T., Degryse, H., Kneer, C.: Is more finance better? Disentangling intermediation and size effects of financial systems. J. Financ. Stab. 10, 50–64 (2014)

Beck, T., Levine, R., Loayza, N.: Finance and the sources of growth. J. Financ. Econ. 58(1–2), 261–300 (2000)

Bist, J.P.: Financial development and economic growth: evidence from a panel of 16 African and non-African low-income countries. Cogent Econ. Finan. 6(1), 1449780 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2018.1449780

Bittencourt, M.: Financial development and economic growth in Latin America: Is Schumpeter right? J. Policy Model. 34, 341–355 (2012)

Breitenlechner, M., Gächter, M., Sindermann, F.: The finance–growth nexus in crisis. Econ. Lett. 132, 31–33 (2015). https://doi.org/10/ghsmqn

Buchanan, B.G., Le, Q.V., Rishi, M.: Foreign direct investment and institutional quality: some empirical evidence. Int. Rev. Finan. Anal. 21, 81–89 (2012). https://doi.org/10/c2r6j5

Carré, E., L’œillet, G.: The literature on the finance–growth nexus in the aftermath of the financial crisis: a review. Comp. Econ. Stud. 60(1), 161–180 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-018-0056-6

Compton, R.A., Giedeman, D.C.: Panel evidence on finance, institutions and economic growth. Appl. Econ. 43(25), 3523–3547 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/00036841003670713

De Gregorio, J., Guidotti, P.E.: Financial development and economic growth. World Dev. 23(3), 433–448 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(94)00132-I

Demetriades, P., Fielding, D.: Information, institutions, and banking sector development in West Africa. Econ. Inq. 50(3), 739–753 (2012). https://doi.org/10/dv5n7t

Djeri, L.D.: Institutional quality and financial development in West Africa Economic and Monetary Union. Global J. Manag. Bus. Res. (2020). https://doi.org/10/ghr5z5

Driscoll, J.C., Kraay, A.C.: Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 80(4), 549–560 (1998). https://doi.org/10/b88vxp

Favara, G.: An empirical reassessment of the relationship between finance and growth. IMF Working Paper, WP/03/123 (2003)

Fernandez, D., Galetovic, A.: Schumpeter might be right-but why? Explaining the relation between finance, development, and growth. Johns Hopkins University SAIS Working Paper in International Economics (1994)

Gani, A., Ngassam, C.: Effect of institutional factors on stock market development in Asia. Am. J. Finan. Acc. 1(2), 103 (2008). https://doi.org/10/dj2c97

Girma, S., Shortland, A.: The political economy of financial development. Oxford Econ. Papers 60(4), 567–596 (2007). https://doi.org/10/d6f8xv

Globerman, S., Shapiro, D.: Global foreign direct investment flows: the role of governance infrastructure. World Dev. 30(11), 1899–1919 (2002). https://doi.org/10/dcmbjp

Goldsmith, R.W.: Financial Structure and Development. Yale University Press (1969)

Haini, H.: Examining the relationship between finance, institutions and economic growth: evidence from the ASEAN economies. Econ. Change Restructuring 53(4), 519–542 (2020). https://doi.org/10/ghrhq2

Hakimi, A., Hamdi, H.: Does corruption limit FDI and economic growth? Evidence from MENA countries. Int. J. Emerging Markets 12(3), 550–571 (2017). https://doi.org/10/ghrkhs

Hassan, M.K., Sanchez, B., Yu, J.-S.: Financial development and economic growth: new evidence from panel data. Q. Rev. Econ. Finance 51(1), 88–104 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2010.09.001

Hausman, J.A.: Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica 46(6), 1251 (1978). https://doi.org/10/bgbj6d

Hoechle, D.: Robust standard errors for panel regressions with cross-sectional dependence. Stata J. Promoting Commun. Stat. Stata 7(3), 281–312 (2007). https://doi.org/10/gf4j23

Hsueh, S.-J., Hu, Y.-H., Tu, C.-H.: Economic growth and financial development in Asian countries: a bootstrap panel Granger causality analysis. Econ. Model. 32, 294–301 (2013)

Ibrahim, S., Abdullahi, A.B., Azman-Saini, W.N.W., Rahman, M.A.: Finance-growth nexus: evidence based on new measures of finance. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 11(1), 17–29 (2017)

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., Mastruzzi, M.: The worldwide governance indicators: methodology and analytical issues. World Bank (2010). https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5430

Khan, A.: Financial development and economic growth. Macroecon. Dyn. 5(3), 413–433 (2001). Cambridge Core

King, R.G., Levine, R.: Finance and growth: schumpeter might be right. Quart. J. Econ. 108(3), 717–738 (1993)

Kutan, A.M., Samargandi, N., Sohag, K.: Does institutional quality matter for financial development and growth? Further evidence from MENA countries. Australian Econ. Papers 56(3), 228–248 (2017). https://doi.org/10/gfhx9c

Law, S.H., Azman-Saini, W.N.W.: The Quality of Institutions and Financial Development (2008)

Law, S.H., Habibullah, M.S.: The determinants of financial development: institutions, openness and financial liberalisation. South African J. Econ. 77(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10/bb4bd4

Law, S.H., Singh, N.: Does too much finance harm economic growth? J. Bank. Finance 41, 36–44 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.12.020

Levine, R.: Financial development and economic growth: views and agenda. J. Econ. Lit. 35(2), 688–726 (1997)

Levine, R.: More on finance and growth: more finance, more growth? Federal Reserve Bank St. Louis Rev. 85, 31–46 (2003)

Levine, R., Loayza, N., Beck, T.: Financial intermediation and growth: causality and causes. J. Monet. Econ. 46(1), 31–77 (2000)

Lucas, R.E.: On the mechanics of economic development. J. Monet. Econ. 22(1), 3–42 (1988)

Luintel, K.B., Khan, M.: A quantitative reassessment of the finance-growth nexus: evidence from a multivariate VAR. J. Dev. Econ. 60(2), 381–405 (1999)

Marques, L.M., Fuinhas, J.A., Marques, A.C.: Does the stock market cause economic growth? Portuguese evidence of economic regime change. Econ. Model. 32, 316–324 (2013)

Minea, A., Villieu, P.: Financial development, institutional quality and maximizing-growth trade-off in government finance. Econ. Model. 27(1), 324–335 (2010). https://doi.org/10/bxb8vw

Murtaza, G., Faridi, M.Z.: Economic institutions and growth nexus: the role of governance and democratic institutions—evidence from time varying parameters’ (TVPs) models. Pakistan Dev. Rev. 55(4), 675–688 (2016). JSTOR. https://doi.org/10/ghrbtf

Naceur, S.B., Ghazouani, S.: Stock markets, banks, and economic growth: empirical evidence from the MENA region. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 21(2), 297–315 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2006.05.002

Nguyen, C.P., Su, T.D., Nguyen, T.V.H.: Institutional quality and economic growth: the case of emerging economies. Theor. Econ. Lett. 08(11), 1943–1956 (2018). https://doi.org/10/ghrkht

Nyasha, S., Odhiambo, N.M.: Do banks and stock markets spur economic growth? Kenya’s experience. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. 7(1), 54 (2015). https://doi.org/10/ghsgg4

Nyasha, S., Odhiambo, N.M.: Financial development and economic growth nexus: a revisionist approach: finance-growth nexus: a revisionist approach. Econ. Notes 47(1), 223–229 (2018). https://doi.org/10/ghr9mb

Popovic, G., Eric, O., Stanic, S.: Trade openness, institutions and economic growth of the western balkans countries. Montenegrin J. Econ. 16(3), 173–184 (2020). https://doi.org/10/gmmj73

Prochniak, M., Wasiak, K.: The impact of the financial system on economic growth in the context of the global crisis: empirical evidence for the EU and OECD countries. Empirica 44(2), 295–337 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-016-9323-9

Rajan, R.G., Zingales, L.: Financial dependence and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 88(3), 559–586 (1998)

Ram, R.: Financial development and economic growth: additional evidence. J. Dev. Stud. 35(4), 164–174 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389908422585

Robinson, J.: The Generalization of the General Theory in the Rate of Interest and Other Essays. Macmillan (1952)

Rousseau, P.L., Wachtel, P.: What is happening to the impact of financial deepening on economic growth? Econ. Inq. 49(1), 276–288 (2011)

Sabir, S., Rafique, A., Abbas, K.: Institutions and FDI: evidence from developed and developing countries. Finan. Innov. 5(1), 8 (2019). https://doi.org/10/ggtctd

Sani, A., Said, R., Ismail, N.W., Mazlan, N.S.: Public debt, institutional quality and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Institutions Econ. 39–64%@ 2232–1349 (2019)

Schumpeter, J.A.: The Theory of Economic Development. Harvard University Press (1912)

Seetanah, B., Ramessur, S.T., Rojid, S.: Financial development and economic growth: new evidence from a sample of island economies. J. Econ. Stud. 36(2), 124–134 (2009)

Shan, J., Morris, A.: Does financial development “Lead” economic growth? Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 16(2), 153–168 (2002). https://doi.org/10/d4b5fj

Shaw, E.S.: Financial Deepening in Economic Development. Oxford University Press (1973)

Singh, R.J., Kpodar, K.R., Ghura, D.: Financial deepening in the CFA Franc zone: the role of institutions. IMF Working Paper, WP/09/113 (2009)

Slesman, L., Baharumshah, A.Z., Azman-Saini, W.N.W.: Political institutions and finance-growth nexus in emerging markets and developing countries: a tale of one threshold. Q. Rev. Econ. Finance 72, 80–100 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2019.01.017

Smolo, E.: Bank concentration and economic growth nexus: evidence from OIC countries. Appl. Finan. Lett. 9, 81–111 (2020). https://doi.org/10/ghsgg7

Smolo, E.: The FDI and economic growth in the western balkans: the role of institutions. J. Econ. Cooperation Dev. 42(4), 147–170 (2021)

Smolo, E.: Finance-growth nexus: evidence from systematically important islamic finance countries. In: 11th Foundation of Islamic Finance Conference (FIFC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (2021b)

Svirydzenka, K.: Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development. IMF Working Papers 16(05), 1 (2016). https://doi.org/10/ggr942

Swamy, V., Dharani, M.: The dynamics of finance-growth nexus in advanced economies. Int. Rev. Econ. Finan. 64 122–146 (2019a). https://doi.org/10/ghr87b

Swamy, V., Dharani, M.: The dynamics of finance-growth nexus in advanced economies. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 64, 122–146 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2019.06.001

Wooldridge, J.M.: Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. MIT Press (2002)

Yang, F.: The impact of financial development on economic growth in middle-income countries. J. Int. Finan. Markets Inst. Money 59, 74–89 (2019). https://doi.org/10/gjm22k

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The data are available upon a reasonable request from the author.

Appendix: Robustness Tests

Appendix: Robustness Tests

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Smolo, E. (2023). The Finance-Growth Nexus and the Role of Institutional Development: A Case Study of the Western Balkan Countries. In: Tufek-Memišević, T., Arslanagić-Kalajdžić, M., Ademović, N. (eds) Interdisciplinary Advances in Sustainable Development. ICSD 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 529. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17767-5_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17767-5_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-17766-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-17767-5

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)