Abstract

In any profession, having a strong and collaborative support network, skilled mentorship, thoughtful sponsorship, timely coaching, and a robust career development plan can make an enormous difference in one’s career trajectory by creating opportunities for advancement and catapulting one into leadership positions (Spector and Overholser, J Hosp Med 14:415, 2019). For women in medicine, the stakes are even higher since women tend to face more barriers, receive less sponsorship, and encounter fewer opportunities for advancement. As a result, women remain woefully underrepresented in the highest ranks in academic medicine (e.g., rank of professor) and leadership positions at academic medical centers (AAMC. 2018–2019 The State of Women in Academic Medicine: Exploring Pathways to Equity. 2018–2019. Retrieved September 20, 2021 from https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2018-2019-state-women-academic-medicine-exploring-pathways-equity; Travis et al., Acad Med 88:1414–1417, 2013).

Because the landscape for women in medicine is different than for men, women are often alone and without the necessary support needed for career success. As women rise up in the ranks of leadership, there are few women at the highest levels to provide support, mentorship, and sponsorship. If a woman does reach a high-level leadership position, she is often isolated and doesn’t have other women peers to provide support and counsel. Therefore, women must navigate their rise to leadership differently. They must cultivate a deep and broad network that includes mentors, sponsors, coaches, and allies and seek career development opportunities that will give them the tools necessary to overcome barriers, achieve advancement, and receive the needed support to sustain turbulent times.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The Importance of Networking

Networking is the process of creating one’s fabric of personal contacts who will provide support, feedback, insight, resources, information, and opportunities throughout one’s career [21]. Many find networking insincere or manipulative, and women often suffer the consequences of having poorly developed professional networks. Building one’s operational, personal, and strategic networks, which allow for adequate mentorship, sponsorship, coaching, and allyship, is vital to supporting a woman’s career. It’s been written that “the alternative to networking is to fail – either in reaching for a leadership position or in succeeding at it,”[21] and it is true. Those who invest time and effort in networking tend to be more successful in their careers than “those who fail to leverage external ties”[21]. Finding a good role model who is able to apply judgment and intuition in order to effectively and ethically network is a good way to build one’s skills as a networker.

Ibarra and Hunter describe three distinct forms of networking, including operational, personal, and strategic, as key components of the evolution of leaders on their quest to career advancement. These various forms of networking are described in Table 12.1. In their study of leaders who are seeking to build networking relationships, the authors found that operational networking helps to manage current responsibilities, personal networking helps to boost personal development, and strategic networking highlights future opportunities and directions [21].

It is important to note that women and men network differently, at different times and sometimes in different settings. Due to the paucity of women in leadership or the highest ranks in medicine and more specifically in pediatrics, women may need to look outside of their specialty, institution, or even discipline to find the needed support network and counsel they seek. Once women achieve leadership positions or success, they must then reach back and help those who are rising up the ranks. In order to change the landscape for future generations of women in medicine, it is imperative to create a network of women at the top who are willing to change the landscape and give other women the opportunities they were not afforded.

Mentorship

In academic medicine, effective mentorship is considered one of the most important determinants of success [36]. Yet women underinvest in key social capital opportunities to establish and maintain mentorship relationships, leaving them at a disadvantage [16]. For women with intersectional identities, mentorship and sponsorship are even more crucial to ensure access to opportunities, achievement of success, and advancement. Tsedale M. Melaku’s research has shown that sponsorship is “critical to Black women’s access to significant training, development, and networking opportunities and advancement” [25]. While Chap. 10 speaks to the importance of male allyship in supporting women in pediatrics, it’s important to note that to really optimize a culture of support for all women, we need to additionally consider how white women should serve as mentors and critical allies for women with intersectionality. “Only 10 percent of Black women and 19 percent of Latinas say the majority of their strongest allies are white, compared to 45 percent of white women” [34]. In order to achieve true equity for all women in pediatrics, white women need to step forward and serve as mentors and key allies for women of color.

A mentor is an experienced and trusted advisor, typically in one’s own field, who uses their knowledge and experience to counsel [23]. Typically, mentorship occurs in a dyadic fashion between a more senior and junior individual, in which the senior mentor provides wisdom, guidance, and support. However, there are various other types of mentoring relationships that are critical to the success of women in medicine. Table 12.2 highlights various types of mentoring relationships that women in medicine often participate in.

Diversity in one’s mentorship team is important for women in pediatrics. Mentors of different genders, races, and ethnicities and from inside and outside one’s organization can offer broader perspectives to challenges. In pediatrics and in most other areas of medicine, men hold the most powerful leadership positions. In order to achieve gender equity, it’s imperative that these men support women’s advancement by being mentors. Women in pediatrics need to prioritize mentoring by actively engaging in networking as outlined above to actively seek and secure mentors.

“People have amazing promise and potential. Each has a unique light within. Mentoring is a privilege, a special trust bringing us closer to another’s nascent spark and the heat at their core. Mentoring is also a generational charge, a responsibility to protect that light, to shield it, nurture it, help another learn how to tend to and control the fire so that it may fuel dreams, collaborations, and change.” – Judy Schaechter, MD, MBA, President and Chief Executive Officer of the American Board of Pediatrics.

Pediatric physician-scientists have their own unique needs for mentorship, as Dr. Sallie Permar, chair of the Department of Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and pediatrician-in-chief at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center and NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital describes:

“Mentorship is critical in all aspects of academic medicine, but particularly in areas that lack representation in academic medicine leadership from the populations we serve. In particular, pediatricians are underrepresented in academic medicine leadership, and it is the interest of children and their future health that may suffer in that setting. Thus, structured mentorship of diverse future pediatrician and pediatrician-scientist leaders is critical to the trajectory of the health of our nation and globe.

Pediatrician-scientists are a specific group that are underrepresented among physician-scientists and declining in number, jeopardizing advancement in cures and prevention of childhood diseases, as well as addressing the origins of costly adult diseases. A disparity in the representation of children’s health in the portfolio of funded physician investigators is a threat to our achievements in lifelong health. Yet the pipeline of pediatric physician scientists is threatened by ballooning medical education debt and relatively low salaries in the field of pediatrics that typically support research, a concentration of pediatric research funding at a small number of large institutions, and a declining number and aging population of mentors.

Pipeline efforts are vital to ensuring progress in basic and translational discoveries that yield improved lifelong health are reliant on mentorship, a key tenant of academic medicine. Mentoring of future pediatrician-leaders and scientists who represent all backgrounds is how we promise a healthier future to our children and the adults they will become.”

Sponsorship

While mentoring is a central component of the leadership journey, sponsorship is more focused on advancement, power, and accelerating the career trajectory, and in many ways, it is more vital for women than mentorship. Some research has shown that having a mentor increases the likelihood of promotion for men, but not for women, perhaps because women’s mentors tend to be less senior that those of their colleagues who are men and therefore don’t have adequate influence to advocate for them [20].

Sponsorship is defined as the “public support by a powerful, influential person for the advancement and promotion of an individual within whom he or she sees untapped or unappreciated leadership talent or potential”[20]. It is also characterized by its bi-directionality: the sponsor and protégé share values and offer each other complementary skill sets. Sponsors have the clout to advocate for a promotion in a public way, connect protégés with senior leaders, come to their aid when their protégé is in trouble, and call in favors on their behalf [19]. A protégé supports their sponsor’s passion and promotes their legacy. They then pay it forward by becoming sponsors themselves.

For women, sponsorship is critically important. For women of color, in particular, sponsorship is an essential component to allow access to significant training, development, and networking opportunities and advancement [20]. But fewer women than men have sponsors. Why is that the case? Unconscious bias on the part of sponsors may play a role as well as women’s underinvestment in seeking sponsors. And it may also be “the similarity principle” as Herminia Ibarra categorizes it:

“Here human nature creates an uneven playing field: People’s tendency to gravitate to those who are like them on salient dimensions such as gender increases the likelihood that powerful men will sponsor and advocate for other men when leadership opportunities arise” [20].

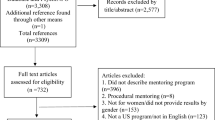

Institutions have an opportunity to close the sponsorship gap by building a strong internal culture of sponsorship by supporting and developing internal sponsorship programs. With a guiding set of principles to ground it, including training regarding gender and race issues, the sponsorship program can have tremendous impact. Magrane et al. have developed an instrument for self- and organizational assessment of mentoring and sponsorship practices leaders in academic engineering use [24]. This assessment has been adapted for academic health science faculty (Fig. 12.1) and can be useful for institutions seeking to develop intentional approaches to leadership development.

Leadership mentoring and sponsoring self-assessment for academic health science faculty [24]

Career/Professional Development Programs

Career/professional development refers to training an individual may participate in with the goal to evolve, improve, or develop their professional skills, often associated with advancement within their given career path. Local and national career development programs have been found to have a positive impact on the promotion and advancement of women in medicine. Women who participate in these types of programs were noted to have greater career satisfaction, improved professional skills (e.g., interpersonal, leadership, negotiation, and networking skills), greater success in being promoted, a more rapid pace to promotion, and lower attrition rates in academic medicine [7, 8, 12, 18, 26].

We encourage women to actively think about pursuing career/professional development at all stages of their career. In selecting a program, women must be strategic and consider timing and skills needed and identify opportunities or challenges they are currently facing or anticipate in their career. As one begins looking at development opportunities, individuals must also reflect on how they will apply the knowledge and skills from the program they are considering to their current position. Women should also actively pursue support for these programs from their institution or employer. Supporting employees or faculty members in obtaining additional career/professional development is an excellent return on investment for institutions for their workforce becomes more skilled, productive, and has a higher likelihood retention.

Table 12.3 details some sample career development programs for women in medicine. Please note this is not an exhaustive list and programs may evolve with time. Rather, this is a list of programs that were well established at the time of publication of this book and are illustrative of the programs that many women in pediatrics have elected to attend.

We would like to highlight two career development programs for women in medicine that have proven impact. The ELAM® program at Drexel University College of Medicine is a prime example of a well-established and extremely successful national professional development program for mid- to senior-level women in academic medicine [17]. The program is a longitudinal part-time fellowship that focuses on expanding the national pool of qualified women candidates for leadership in academic medicine, dentistry, public health, and pharmacy and aims to ensure that there is gender equity at every level of leadership. The curriculum of this program is designed to address four fundamental competencies, including (1) strategic finance and resource management, (2) personal and professional leadership effectiveness, (3) organizational dynamics, and (4) communities of leadership practice. Since 1995, more than 1200 women have graduated from the program and have gone on to lead in high-level positions including as provosts, presidents, deans, and chairs at institutions and organizations around the country and the world. Roughly 140 of the alumnae are in the field of pediatrics, 27 of whom are chairs of their department.

The ELAM program is extremely successful because it makes use of its strong national alumnae network, incorporating them as faculty, mentors, and coaches for the current fellows. The program employs functional and facilitated peer group mentoring as part of the program’s experiential learning process and also within small learning communities of six program fellows facilitated by one senior individual who is usually a graduate of the program. The benefits go in several ways – the fellows receive guidance and support from their peers and their advisor. The advisor receives enrichment from the fellows and returns to her home institution with new outlooks and perspectives. Programs such as ELAM are critically important for women in medicine, and leaders and mentors in pediatrics should strongly encourage and sponsor women at their institution to attend the program.

The Wake Forest School of Medicine (WFSM) Career Development for Women Leaders (CDWL) is a local, competitive program developed for mid- and senior-level women faculty who are in leadership roles or aspire to be leaders, as well as women staff at the VP level of healthcare administration [33]. This program was created in 2008 as the result of an ELAM’s fellow Institutional Action Project, and 13 classes have completed the program for a total of 245 program graduates as of June 2021. Offered over 9 months, women attend one full-day session per month. It is an affordable, local option that allows more women to participate in leadership education. Women from diverse professional backgrounds from multiple institutions including WFSM, Wake Forest University, and surrounding universities come to the program to exchange ideas and foster cross-campus collaboration.

The program modules mirror many of ELAM’s and include team building, institutional finances, decision-making strategies for leaders, and creating and sustaining diversity. CDWL’s internal data reports that 56% of the 245 program graduates have accepted a new leadership role, and of those, 36% accepted more than one new leadership role. Nineteen percent of 245 CDWL program graduates have left their institution, and of those, 52% left for bigger leadership roles at new institutions [10].

Professional Coaching

Another critical resource in helping women to advance, overcome barriers, and achieve their full potential in medicine is professional coaching. Coaches provide specific instruction, assist at increasing performance at work, and assist with professional development. They are not sounding boards; they help clarify goals, ask for intentional actions and behaviors, and keep their clients accountable and on track with their plans. For those earlier in their career, executive coaching has been found to effectively reduce physician burnout, which impacts women more than men [5] – women have a 60 percent greater odds of reporting burnout compared with men – and is a phenomenon that has only increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and its continuing aftermath. Dyrbye et al. conducted a pilot trial for professional coaching for 88 physicians at Mayo Clinic sites and found that coaching can be an effective intervention for addressing burnout and quality of life and can aid in building resilience and that developing a formal, institutionally sponsored professional coaching experience can improve physician well-being [15]. For people further along in their career, professional coaches can help with transitions into leadership positions.

Controlling Your Own Destiny

As women in pediatrics seek to build their networks, create their mentorship team, and find strategic sponsors, they must also recognize that they are the most important person in determining the path to success. During medical school, residency, and fellowship training, built-in support and mentorship structures help to provide critical guideposts in one’s career development. However, once training ends, women often find themselves floundering in a vast new world. While many practices and institutions have some infrastructure for career or faculty development and mentorship, it is never to the level that one finds in training. Therefore, it is critical that women recognize the importance of having a strong sense of responsibility for their success while they capitalize upon the structures that exist for their own development and advancement.

While we must create pediatric healthcare institutions that support women in their development and advancement, women must be the main driver of their success. Women must ensure they are driving their mentoring experience by managing up, setting an agenda, and asking for the things they need [11]. Mentors and sponsors who are more senior in their career are often very busy and have limited time. Therefore, women in pediatrics must maximize their time and asks from their mentors and sponsors by setting agendas for meetings, making realistic asks of them, and learning how they can most effectively and efficiently get what they need from them [9]. Women must deliver on their assigned or promised tasks, and project eagerness and excitement to be a part of the mentoring relationship. Regardless of their temperament, preferred communication style, and comfort with building networks, they must invest in the social capital of developing and maintaining strong local and national networks. Women in pediatrics must ask mentors and sponsors to create connections to key people in their area of interest or who can create opportunities for them in the future.

As women rise in leadership or higher academic ranks, it is their responsibility to intentionally reach out to women joining the field and provide assistance, advice, and sponsorship. Even if these senior women were not afforded appropriate mentorship, sponsorship, or networking opportunities early in their career, they must change the narrative and create a culture where we “lift others as we rise.” Women in senior positions in pediatrics must continually ask themselves who needs to be lifted up, whose voice needs to be heard or amplified, and who needs to be given a chance at a new opportunity. In order to truly change the destiny for women in pediatrics, women must support one another, create networks, sponsor each other, and find power in collaboration. As Shelley Zalis stated, “There is a special place in heaven for women who support other women” [35].

References

AAMC. 2018–2019 The State of Women in Academic Medicine: Exploring Pathways to Equity. 2018–2019. Retrieved September 20, 2021 from https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/2018-2019-state-women-academic-medicine-exploring-pathways-equity.

AAMC Early Career Women Faculty Leadership Development Seminar. Retrieved October 20, 2021 from https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/leadership-development/ewims.

AAMC Mid-Career Women Faculty Leadership Development Seminar. Retrieved October 21, 2021 from https://www.aamc.org/professional-development/leadership-development/midwims.

Advancing Pediatric Leaders. Retrieved October 20, 2021 from https://www.academicpeds.org/programs-awards/advancing-pediatric-leaders/.

Alexander L, Bonnema R, Farmer S, Reimold S. Executive coaching women faculty: a focused strategy to build resilience. Phys Leadership J. 2020;7(1):41–4.

APPD Leadership in Educational Academic Development (LEAD). Retrieved October 20, 2021 from https://www.appd.org/resources-programs/educational-resources/appd-lead/.

Chang S, Guindani M, Morahan P, Magrane D, Newbill S, Helitzer D. Increasing promotion of women Faculty in Academic Medicine: impact of National Career Development Programs. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(6):837–46. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.8044.

Chang S, Morahan PS, Magrane D, Helitzer D, Lee HY, Newbill S, Cardinali G. Retaining Faculty in Academic Medicine: the impact of career development programs for women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(7):687–96. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5608.

Chopra V, Saint S. What mentors wish their mentees knew. 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/11/what-mentors-wish-their-mentees-knew.

Correspondence from Wake Forest School of Medicine WIMS Career and Leadership Development Programs. November 2021.

Cruz M, Bhatia D, Calaman S, Dickinson B, Dreyer B, Frost M, Spector N.. The Mentee-Driven Approach to Mentoring Relationships and Career Success: Benefits for Mentors and Mentees. MedEdPORTAL. 2015, 11. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10201.

Danhauer SC, Tooze JA, Barrett NA, Blalock JS, Shively CA, Voytko ML, Crandall SJ. Development of an innovative career development program for early-career women faculty. Glob Adv Health Med. 2019;8:2164956119862986. https://doi.org/10.1177/2164956119862986.

Drexel University College of Medicine Faculty Launch Program. Retrieved October 15, 2021 from https://drexel.edu/medicine/faculty-and-staff/faculty-and-staff-resources/faculty-launch-program/.

Duke University School of Medicine LEADER Program. Retrieved October 15, 2021 from https://medschool.duke.edu/about-us/faculty-resources/faculty-development/our-programs/leadership-development-researchers.

Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Gill PR, Satele DV, West CP. Effect of a professional coaching intervention on the well-being and distress of physicians: a pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(10):1406–14. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2425.

Eagly A, Carli L. Women and the Labyrinth of Leadership. 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2021 from https://hbr.org/2007/09/women-and-the-labyrinth-of-leadership.

Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine program. Retrieved October 7, 2021 from https://drexel.edu/medicine/academics/womens-health-and-leadership/elam/.

Helitzer DL, Newbill SL, Morahan PS, Magrane D, Cardinali G, Wu CC, Chang S. Perceptions of skill development of participants in three national career development programs for women faculty in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):896–903. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000251.

Hewlett SA. The sponsor effect: how to be a better leader by investing in others. Harvard Business Review Press; 2019.

Ibarra H. A lack of Sponsorship is Keeping Women from Advancing into Leadership. 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2021 from https://hbr.org/2019/08/a-lack-of-sponsorship-is-keeping-women-from-advancing-into-leadership.

Ibarra H, Hunter ML. How Leaders Create and Use Networks. Harvard Business Review. 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2021 from https://hbr.org/2007/01/how-leaders-create-and-use-networks.

Kuzma N, Skuby S, Souder E, Cruz M, Dickinson B, Spector N, Calaman S. Reflect, advise, plan: faculty-facilitated peer-group mentoring to optimize individualized learning plans. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(6):503–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.06.002.

Loethen J, Ananthamurugan M. Women in medicine: the quest for mentorship. Mo Med. 2021;118(3):182–4.

Magrane D, Morahan PS, Ambrose S, Dannels SA. Competencies and practices in academic engineering leadership development: lessons from a National Survey. Soc Sci. 2018;7(10):171.

Melaku T, Beeman A, Smith D, Johnson WB. Be a Better ALly. Harvard Business Review. 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2021 from https://hbr.org/2020/11/be-a-better-ally.

Nowling TK, McClure E, Simpson A, Sheidow AJ, Shaw D, Feghali-Bostwick C. A focused career development program for women faculty at an academic medical center. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018;27(12):1474–81. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.6937.

Raluca C. How many types of mentoring are there? 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2021 from https://blog.matrixlms.com/how-many-types-of-mentoring-are-there/.

Serwint JR, Cellini MM, Spector ND, Gusic ME. The value of speed mentoring in a pediatric academic organization. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(4):335–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2014.02.009.

Society of Hospital Medicine's Leadership Academy. Retrieved October 20, 2021 from https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/event/leadership-academy/.

Spector ND, Overholser B. Leadership and professional development: sponsored; catapulting underrepresented talent off the cusp and into the game. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(7):415. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3214

Thorndyke LE, Gusic ME, Milner RJ. Functional mentoring: a practical approach with multilevel outcomes. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2008;28(3):157–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.178.

Travis EL, Doty L, Helitzer DL. Sponsorship: a path to the academic medicine C-suite for women faculty? Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1414–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a35456.

Wake Forest School of Medicine Career Development for Women Leaders Program. Retrieved October 19, 2021 from https://school.wakehealth.edu/About-the-School/Faculty-Affairs/Faculty-Development/Women-in-Medicine-and-Science/Career-Development.

White employees see themselves as allies—but Black women and Latinas disagree. Retrieved December 20, 2021 from https://leanin.org/research/allyship-at-work.

Zalis S. Power of the Pack: Women Who Support Women are more Successful. 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/shelleyzalis/2019/03/06/power-of-the-pack-women-who-support-women-are-more-successful/?sh=cb454ac1771a.

Zerzan JT, Hess R, Schur E, Phillips RS, Rigotti N. Making the most of mentors: a guide for mentees. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):140–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181906e8f.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

O’Toole, J.K., Overholser, B., Spector, N.D. (2022). Networking, Mentorship, Sponsorship, Coaching, and Career Development Activities to Support Women in Pediatrics. In: Spector, N.D., O'Toole, J.K., Overholser, B. (eds) Women in Pediatrics . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98222-5_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98222-5_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-98221-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-98222-5

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)