Abstract

Gender disparities for female physicians in academic medicine are longstanding. Female pediatric cardiologists experience inequities in scholarship opportunities, promotion, leadership positions, and compensation. Mentorship groups have been successfully implemented in other subspecialities with promising results. We created a peer mentorship group for female pediatric cardiologists in the Northeast and completed a needs assessment survey of eligible participants. Our goal was to better understand the current challenges and identify resources to overcome these barriers. Our objectives were to (1) describe the creation of a novel mentorship program for female pediatric cardiologists and trainees in the Northeast United States, and (2) report the results of a formal needs assessment survey of all eligible participants. All female pediatric cardiology fellows and practicing pediatric and adult congenital heart disease specialists from 15 academic centers in New England were invited to join a free group with virtual meetings. A formal needs assessment survey was provided electronically to all eligible members. The vast majority of respondents agreed that the Women in Pediatric Cardiology (WIPC) group is a valuable networking and mentorship experience (90%) and would recommend this group to a colleague (95%). Members have witnessed or experienced inequities in a broad range of settings. Common challenges experienced by respondents include dependent care demands, lack of mentorship, inadequate research support, and inequitable clinical responsibilities. Resources suggested to overcome these barriers include mentorship, sponsorship, transparency in compensation, and physician coaching. Mentorship groups have the potential to address many challenges faced by women in medicine. The WIPC Northeast program provides a forum for community, collaboration, education, and scholarship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gender disparities for female physicians in academic medicine are longstanding. Inequities in promotion, leadership positions, scholarship opportunities, and compensation have been consistently demonstrated across medical specialties [1,2,3]. Compared to their male counterparts, women in medicine are less likely to hold leadership positions and less likely to be promoted to rank of associate or full professor [4,5,6]. Female physicians receive 25% less compensation over the course of a career than their male counterparts [7,8,9,10]. Furthermore, female physicians have been shown to experience higher rates of burnout then their male colleagues, driven by unequal patient expectations, role expectations outside of work, and personal experiences within the workplace [11,12,13]. These trends have been demonstrated in the field of pediatric cardiology as well [7].

The COVID-19 pandemic further exposed and exacerbated challenges for women faculty in medicine trying to advance their careers during a time of disruption and uncertainty [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. In a survey of pediatric cardiologists in the Northeast United States, female pediatric cardiologists disproportionately reported decreased career satisfaction, decreased academic productivity, and increased burnout. Female respondents were also more likely to report considering leaving medicine for a different career path [27]. Given this concerning context, we identified a need for support and collaboration among female pediatric cardiologists in New England and launched the Women in Pediatric Cardiology (WIPC) group in March 2021.

Mentorship groups for female physicians have been successfully implemented in several specialties, including anesthesiology, emergency medicine, neonatology, and radiology. These groups have demonstrated encouraging results, including increased access to research opportunities, mentoring, and networking [29,30,31,32]. Improved access to mentorship has been associated with better career satisfaction and increased success in academic medicine, which may help increase retention of women faculty in academia [33,34,35]. The WIPC was founded to bring women together and advance women forward. The goals of the group were to provide a forum for discussion, friendship, mentorship, and collaboration. We subsequently performed a formal needs assessment survey to better understand the challenges faced by women in pediatric cardiology, resources needed to overcome these barriers, experiences of gender inequity in our field, and topics important to the group to discuss at upcoming meetings.

Methods and Materials

Recruitment

The Women in Pediatric Cardiology group was launched in March 2021. The initial idea evolved during informal discussions at a regional meeting of the New England Congenital Cardiology Association (NECCA). Members from three academic centers collaborated in the formation and development of the group after informally gathering perspectives from around the region. Potential participants included all female fellows in training and practicing pediatric and adult congenital heart disease specialists from the 15 academic centers in New England. Participants were invited via email to join the initial virtual meeting held via Zoom. Email serves as the primary route of communication and recruitment, but active participants have also encouraged their colleagues by word-of-mouth to join the meetings.

Curricular Design

The initial meeting was titled, “Are you Ok? Struggles and silver linings during the pandemic.” The meeting topic was inspired by the general sentiment that exhaustion and burnout were becoming increasingly common among female pediatric cardiologists in New England. 50% of eligible pediatric cardiologists in the region joined the inaugural meeting, which allowed for open discussion of the challenges facing practicing cardiologists as well as a forum to brainstorm how the WIPC might serve to address these challenges. Subsequent meetings have continued to have representation from most of the academic centers in New England, with average virtual attendance of ~ 40 members (ranging from 20–65) per meeting. Meeting topics and presenters were initially selected by the founding members of the group. After the first meeting, many members provided feedback with topic and presenter suggestions. In addition, the formal needs assessment solicited recommendations that now almost exclusively inform the curriculum.

Membership in the WIPC is free. Meetings have been largely virtual, held during one-hour mid-day sessions during the work week. Each meeting invitation includes recent articles of interest that are often referenced during the discussion. During a regional cardiology conference, the WIPC group hosted an evening working session to further brainstorm and plan for future directions of the group. All meetings and WIPC activities have thus far occurred without any funding.

Needs Assessment Survey

Given the high immediate uptake and enthusiasm, associated with a previously unmet need, we performed a formal needs assessment to inform future curriculum development. Our goal was to better understand the challenges faced by women in pediatric cardiology, resources needed to overcome these barriers, experiences of gender inequity in our field, and topics important to the group to discuss at upcoming meetings. The information garnered has informed meeting logistics and an evolving curriculum designed to promote career longevity, work-life integration, professional development, and academic promotion, with an overall aim to address gender inequities in academic pediatric cardiology.

Study Design

Members of the WIPC were surveyed anonymously using an online REDCap-based survey that was distributed via email to all eligible participants between March 2022 and May 2022. This was a prospective descriptive survey study. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School approved this study. This study was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines. This survey was designed by the authors and piloted among practicing physicians at Boston Children’s Hospital, Hasbro Children’s Hospital, and University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School.

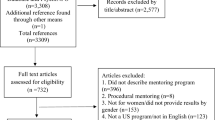

Eligible participants included 94 fellows in training and practicing female pediatric and adult congenital heart disease specialists in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. Participants were identified by a search of faculty listings at academic pediatric hospitals and private practices.

Data Collection

The survey collected demographic information including age, race, dependents at home, childcare arrangements, and support system at home. It also collected career information including years since training, primary work location, primary area of focus within the field of pediatric cardiology, center size, call group size, academic rank, and leadership positions. Participants were asked which challenges to academic promotion and professional development they have experienced, and which resources could help overcome these barriers. Open responses were encouraged. Participants were asked about gender inequities that they have experienced or witnessed in the realms of leadership, compensation, training, scholarship, and academic promotion. The survey also collected data on meeting logistics, future meeting topics, future meeting guest speakers, advocacy opportunities, and satisfaction with the group thus far.

Statistical Analysis

For discrete variables, frequencies and percentages of the total sample were calculated and for continuous variables, mean and standard deviation were calculated.

Results

Demographics

This survey was sent to 77 female pediatric and adult congenital cardiologists and 17 female pediatric cardiology fellows from the 6 states in New England, including 15 academic sites. There were 59 survey respondents for a response rate of 63%. Demographic variables for respondents can be found in Table 1.

90% of respondents agree that the Women in Pediatric Cardiology group is a valuable networking and mentorship experience. 71% have been able to join at least one meeting. The preferred timing of meetings is mid-day. Alternating meeting days/times and recording meetings for those who are unable to make it were requested. 95% would recommend this group to a colleague.

Gender Inequity

Survey respondents were asked if they had experienced or witnessed gender inequities in academic promotion, scholarship, residency/fellowship training, compensation, and leadership. See Fig. 1 for results.

Survey respondents could also provide open-ended responses in this section. These open-ended responses highlighted themes of inequitable opportunity and unequal expectations for female cardiologists. Highlighted responses included “my male co-fellows are treated very differently than I am—by attendings, nurses, leadership. I feel as though I need to work harder (and get volunteered to organize things) with little recognition or reward.” Another response noted: “As a trainee, academic opportunities [were] offered more frequently to male colleagues; same ideas considered less seriously than from male colleagues.” An additional theme was inequity experienced by female trainees who had children during cardiology fellowship training: “[There is a] negative perception for having a child during fellowship.” Respondents also reported feeling there was less “buy-in” for their training.

Perceived and observed inequities extended beyond training and were widespread. One response highlighted “Compensation inequity, lack of mentorship, lack of opportunity, lack of champions or those who want one to succeed … lack of administrative and clinical assistance, inequity in promotion and who is advanced.” Additionally, “In many subspecialties in Cardiology there are minimal number of women or fellows such as interventional cardiology”. Also, “there is a minimal amount of women carrying leadership positions.” Respondents reported “[There is a] lack of understanding that decreased availability for off hours events did not equal decreased ability, interest and potential.” Many responses highlighted the challenges of navigating demands outside the hospital.

Barriers to Academic Promotion and Professional Development:

Survey respondents were asked about the most common barriers and challenges unique to being a female in training and/or practicing pediatric and adult congenital cardiology. See Fig. 2 for full results. Survey respondents could also provide open-ended responses to this question. Open-ended responses highlighted the demands of pregnancy and dependent care during training and early career. Several respondents noted the lack of women in leadership positions as a barrier, and several noted lack of mentors or inconsistent mentorship as a challenge. Several respondents noted that there are “inequitable citizenship tasks not directly work-related, inequitable distribution of patient-care and family-facing tasks such as difficult family conversations/multidisciplinary meetings” as well as “Items that do not help with promotion or career advancement have been typically performed by women.”

Resources Needed

Survey respondents were asked which resources could help overcome barriers to academic promotion and professional advancement. Respondents were encouraged to select up to 3 of the provided responses. The most common responses were mentorship (68%), administrative assistance (61%), transparency of salary/bouses (59%), increased compensation (54%), and research assistance (49%). Additional resources included clinic scribe (44%), more role models (41%), physician coaching (41%), affordable childcare (37%), mentorship/sponsorship from an outside institution (31%), supportive family leave policies (25%), and flexible tenure policies (22%).

Open-ended responses highlighted the need for female leaders to be more visible as role models and the need for improved mentorship and sponsorship within our region. One respondent noted, “I think having equal time for paternity leave, and for men to use the full amount of time given is a step in the right direction of creating this equality mindset.” Several respondents identify a need for coaching from peers and desire to have more “senior women sharing tricks of the trade.”

Curricular Design

Meeting topics have been informed by the survey results and participant feedback. Presentations and panel discussions have addressed imposter syndrome, sponsorship/mentorship, reducing physician burnout with an introduction to physician coaching, gender inequity in compensation, how to advocate for yourself at work and navigating mid-career challenges. See Table 2 for full list of meeting topics. Speakers have included practicing pediatric cardiologists in the region, a pediatric critical care physician, a physician coach, and a nationally recognized female entrepreneur and author, among others. The meetings with the highest attendance included: “Find your power: How to advocate for yourself at work,” “Navigating Mid-career challenges,” “How to do Scholarship Right.” Future meeting topics suggested in the survey include navigating fellowship as a woman, retirement/financial planning, and a request for additional multigenerational panel discussions.

Discussion

Despite great progress across the field of medicine, gender disparities for women physicians persist. According to the American Association of Medical Colleges, in 2018–2019 women now make up 41% of full-time faculty in academic medicine. However, women remain underrepresented in leadership roles, with women representing only 25% of full professors, 18% of department chairs, and 18% of medical school deans [28]. From 1979 to 2018, Richter and colleagues demonstrated that women physicians in academic centers were less likely than men to be promoted to rank of associate or full professor, with no narrowing in the gap over these 35 years [4]. Given that over half of current medical student graduates, pediatric residents and pediatric cardiology fellows in the United States are female [28], we need to better understand the barriers that disadvantage women in academic medicine and identify solutions to improve gender equity in promotion, leadership, and compensation.

The WIPC Northeast group has, thus, far succeeded in bringing female pediatric cardiologists and trainees together to highlight shared experiences and brainstorm solutions to our collective challenges. Our topics and speakers have been varied and inspiring. Enthusiasm for the group was high from the beginning, and there has been consistent attendance and growing participation. There was a 63% response rate to the needs assessment survey, reflecting membership engagement and speaking to the high level of investment in the growth and success of the group. The needs assessment results highlight consistent themes, including the experience of being offered fewer academic opportunities, feeling that there was less “buy-in” for training, and difficulty identifying mentors or champions within a specific area of interest. Given that majority of survey respondents have experienced or witnessed gender inequities in academic promotion, scholarship, compensation, and leadership, it is imperative that our group collaborate to identify solutions to these longstanding problems.

The WIPC group is committed to progress for female pediatric cardiologists in our region, and we strive to use the lessons from the needs assessment to inform future directions. We anticipate formalizing a one-on-one mentorship program, applying for grant funding, arranging for additional outstanding speakers, facilitating small group sessions to collaborate on scholarship or other projects, and working together to support the promotion and advancement of each of our members. Given that our members are from multiple academic centers and include a range of academic rank from fellows to professors, we are uniquely positioned to foster the practice of sponsorship across the region. We strive to create a framework that is relevant and transferrable to other specialties. We have recently expanded to include female pediatric cardiologists at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and we are optimistic that the group could further expand to a include cardiologists from a greater geographic region. We continue to consider how best to include men in the group, and anticipate more formally soliciting input and participation from our male colleagues. Lastly, we remain committed to using our group to build connections through mentorship, pay forward advice and opportunities, and advocate for women to promote work-life integration, academic productivity, and career longevity.

References

Rochon PA, Davidoff F, Levinson W (2016) Women in academic medicine leadership: has anything changed in 25 years? Acad Med 91(8):1053–1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001281

Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, Poorman JA, Larson AR, Salles A, Oxentenko AS, Silver JK (2019) Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics 144(5):e20192149. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2149

Feigofsky S (2021) And then she vanished. JACC Case Rep 3(9):1241–1243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccas.2021.04.025

Richter et al (2020) Women Physicians and Promotion in Academic Medicine. N Engl J Med 383:2148–2157

Freed GL, Moran LM, Van KD et al (2016) on behalf of the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics. Current Workforce of General Pediatricians in the United States. Pediatrics 137:e20154242

Association of American Medical Colleges (2018) Physician Specialty Data Report. Table 1.3. Number and Percentage of Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017.

Escudero C, Shaw M et al (2021) Mind the gap: sex disparity in salaries amongst pediatric and congenital cardiac electrophysiologists. Heart Rhythm. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2021.06.049

AAMC Faculty Salary Survey 2020

Wang T, Douglas PS, Reza N (2021) Gender gaps in salary and representation in academic internal medicine specialties in the US. JAMA Intern Med 181(9):1255–1257. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3469

Gottlieb AS, Jagsi R (2021) Closing the gender pay gap in medicine. N Engl J Med 385(27):2501–2504

West C, Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T (2018) Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 283:516–529

McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, Shugerman R, Nelson K et al (2000) The work lives of women physicians: results from the physician work life study. J Gen Intern Med 15:372–80

Rittenberg E, Liebman JB, Rexrode KM (2022) Primary care physician gender and electronic health record workload. J Gen Intern Med 37(13):3295–3301

Higginbotham E, Dahlberg M (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on the careers of women in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/26061.

Bernard MA, Lauer M (2021) The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Extramural Scientific Workforce- Outcomes from an NIH-Led Survey. Available at: https://nexus.od.nih.gov/all/2021/03/25/the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-the-extramural-scientific-workforce-outcomes-from-an-nih-led-survey/. Accessed 12 April 2021.

Andersen JP, Nielsen MW, Simone NL, Lewiss RE, Jagsi R (2020) COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. Elife 9:e58807–e58807

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on the careers of women in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Ranji U, Frederiksen B, Salganicoff A, Long M (2021) Women, work and family during COVID-19: findings from the KFF women’s health survey. Women’s Health Policy

Soares A, Thakker P et al (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on dual-physician couples: a disproportionate burden on women physicians. J Women’s Health 30(5):665–671

Brubaker L (2020) Women physicians and the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Am Med Assoc 324(9):835–836

Jones Y, Durand V, Morton K et al (2020) Collateral damage: how COVID-19 is adversely impacting women physicians. Soc Hosp Med. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3470

Madriago E, Ronai C. Virtual Cardiology-Views From a Muted Microphone. JAMA Cardiology. November 2020. Volume 5, Number 11.

Reza N, DeFilippis E, Michos E (October 2021) The cascading effects of COVID-19 on women in cardiology. Circulation 143:615–617

Langin K (2021) Pandemic hit academic mothers especially hard, new data confirm. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.caredit.abh0110

Delaney R, Locke A, Pershing M (2021) Experiences of a health system’s faculty, staff and trainees’ career development, work culture and childcare needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 4(4):e213997. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.3997

Ferns S, Gautam S, Hudak M (2020) COVID-19 and gender disparities in pediatric cardiologists with dependent care responsibilities. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2021; 147:137–142 American Board of Pediatrics, Pediatric Physicians Workforce Data Book, 2019–2020, Chapel Hill, NC: American Board of Pediatrics, 2020.

Laraja K, Mansfield L, Gauthier N et al (2022) Disproportionate negative career impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on female pediatric cardiologists in the Northeast United States. Pediatr Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-022-02934-9

Pollard EM, Sharpe EE, Gali B, Moeschler SM (2021) Closing the mentorship gap: implementation of speed mentoring events for women faculty and trainees in anesthesiology. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle) 2(1):32–36. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2020.0095

Gaetke-Udager K, Knoepp US, Maturen KE, Leschied JR, Chong S, Klein KA, Kazerooni E (2018) A women in radiology group fosters career development for faculty and trainees. AJR Am J Roentgenol 211(1):W47–W51. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.17.18994

Marshall AG, Sista P, Colton KR, Fant A, Kim HS, Lank PM, McCarthy DM (2019) Women’s night in emergency medicine mentorship program: A SWOT analysis. West J Emerg Med 21(1):37–41. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2019.11.44433

Kamel SI, Itani M, Leschied JR, Ladd LM, Porter KK (2021) Establishing a women-in-radiology group: a toolkit from the American Association for Women in Radiology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 217(6):1452–1460. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.21.25966

DeCastro R, Griffith KA, Ubel PA, Stewart A, Jagsi R (2014) Mentoring and the career satisfaction of male and female academic medical faculty. Acad Med 89:301–311

Farkas AH, Bonifacino E, Turner R, Tilstra SA, Corbelli JA (2019) Mentorship of women in academic medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 34:1322–1329

Parwani P, Han JK, Singh T, Volgman AS, Grapsa J (2020) Raft of otters: women in cardiology: let us stick together. JACC Case Rep 2(12):2040–2043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.006

Funding

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by KL, LM, and LS. The first draft of the manuscript was written by KL and LM, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study has been approved by the institutional committee of University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Laraja, K., Mansfield, L., Lombardi, K. et al. A Novel Approach to Mentorship in Pediatric Cardiology: A Group for Women. Pediatr Cardiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-024-03576-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00246-024-03576-9