Abstract

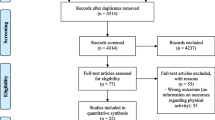

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is routinely performed in younger patients who desire to be active in fitness and recreational sports and enjoy the benefits of a healthy lifestyle. This chapter provides the most updated physical activity guidelines for adults from the American Heart Association. We performed an extensive literature review, and data are summarized from 21 studies that detailed recreational and sports activities patients participated in after TKA. This included types of activities, frequency of participation, and whether symptoms or limitations occurred for future patient counseling considerations. Details are provided for eight studies that used accelerometers to measure physical activity 6–12 months postoperatively, of which only three determined the percent of patients who achieved AHA recommended PA guidelines. Current recommendations for activities allowed after TKA from various orthopedic societies and a systematic review are included.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

10.1 Introduction

In 2013, Weinstein et al. [1] calculated that 655,800 total knee arthroplasty (TKA) recipients in the USA were 50–59 years old and 984,700 patients were 60–69 years old, indicating a large number of individuals that were expected to be active in fitness and recreational activities. Subsequent studies showed a disproportionate increase in the percentage of younger individuals (under the age of 60 years) requiring TKA [2, 3]. This appears to be especially true in individuals that participate in recreational activities over their lifetime who developed knee osteoarthritis (OA) [4,5,6] and in patients who sustain athletic injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures that underwent meniscectomy [7,8,9,10,11,12].

TKA is performed in many athletes, as well as individuals who wish to resume a physically active lifestyle after surgery. These patients have high preoperative expectations [13,14,15] that correlate strongly with postoperative patient satisfaction [14, 16, 17], as detailed in Chap. 12. Therefore, the assessment of which recreational activities are resumed postoperatively is important to determine for preoperative patient counseling and a goal-oriented rehabilitation program to accomplish patient expectations. In addition, objective measurement of the level of physical activity (PA) using validated activity monitors provides realistic data regarding changes in parameters such as percent of time spent in sedentary behaviors compared with light, moderate, or vigorous activities; step counts; time spent walking; distance achieved; and so on. Finally, the determination of whether symptoms of pain and/or swelling occur with recreational activities is also important to assess the ability of TKA to return patients to an active lifestyle, including aerobic fitness, and achieve high levels of satisfaction. This chapter represents an update of the authors’ previous systematic review [18] of this topic in published literature through October 2020.

10.2 Current Physical Activity Guidelines for Healthy Adults

In 2018, the American Heart Association (AHA) updated its guidelines for OA for healthy individuals (Table 10.1) [19, 20]. The guidelines were based on the work of a 17-member advisory committee that extensively reviewed the literature on PA and health [21]. Evidence was rated as strong, moderate, limited, or not assignable and was based on risk factors for cardiovascular disease that can be modified by PA, including blood pressure, blood glucose, blood lipids, and body weight.

Recommendations for substantial health benefits for all healthy adults (aged ≥18) were at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity PA a week, or 75–150 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity. During moderate-intensity activity, a person can talk but not sing. During vigorous-intensity activity, a person cannot say more than a few words without pausing to catch their breath. In addition, muscle-strengthening exercises of moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups should be performed at least 2 days a week. Adults aged ≥65 years were also encouraged to do multicomponent PA that includes balance training. They were advised to determine their level of effort for PA according to their l evel of fitness and whether any chronic conditions were present.

The guidelines allow for a cumulative effect of PA throughout the week. Therefore, the first recommendation was that “adults should move more and sit less throughout the day. Some physical activity is better than none.” Therefore, sedentary patients who begin to perform some PA, such as taking the stairs or parking further from a store, could be expected to achieve some benefits.

The 2018 CDC Physical Activity Guidelines [22] further defined activity in terms of metabolic equivalents (METs) , which is the most commonly used unit to measure PA. One MET is the rate of energy expenditure while sitting at rest, 1.3 for sitting and reading, 2.0 for walking slowly, 3.3 for walking at 3 miles per hour, and 8.3 for running at 5 miles per hour. Vigorous-intensity activity requires >6.0 METs; moderate-intensity activity, 3.0 to <6.0; light-intensity activity, 1.6 to <3.0; and sedentary activity ≤1.5. PA is also reported in terms of frequency (sessions of moderate-to-vigorous PA per day or week), duration (length of each session), and intensity (in METs). Volume is calculated in MET minutes or MET hours per day or week. The use of personal devices (pedometers and accelerometers) to measure PA allows for volume to be expressed as activity counts or step counts during a period of time.

10.3 Sports and Recreational Activities After TKA

We assessed data from 21 studies that detailed recreational and sports activities patients participated in postoperatively (Table 10.2) [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. The studies reported a wide range of patients that returned to recreational activities (25–100%, Fig. 10.1). The mean percentages of patients that participated in the most common activities including walking, bicycling (stationary or road), hiking, swimming, dancing, fitness training or classes such as aerobic or aquatic, and golf are shown in Fig. 10.2. Evidence was not routinely available regarding the number of sports patients participated in on a weekly basis, although some studies indicated patients took part in more than one sports activity [27, 38, 40]. Frequency of participation was highly variable due to the differing methods reported that included the number of days/week [25, 38], number of days/month [36], mean hours/week [28, 32, 43], mean minutes/week [33], and mean number of times per week any activity was performed [39, 40] (Table 10.3).

Only a few studies described symptoms or limitations that occurred with activity [36, 38, 43, 44]. A “major limitation” during participation was found in 14% in one study [44]. Pain in the knee was reported during activity in 16% in one study [43] and in 17% in another (while golfing) [36]. One investigation [38] reported that 26% of patients had pain in their knee and 26% had a feeling of instability during participation. Factors responsible for the inability to return to PA were usually other musculoskeletal problems or persistent pain in the TKA joint [23, 31, 37, 38, 43].

Factors that influenced return to recreational activities included higher preoperative levels of activity [23, 26, 27], higher educational level [24], male gender [37], and body mass index less than 30 [37]. Most studies found that younger patient age at TKA led to higher postoperative activity levels (<70 years [37], <65 years [33], or “younger” age [26]). There were significant correlations found between University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) activity scores and SF-36 and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) scores in one study [29], and between patient activity levels (high, medium, and low impact) and Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) sports, KOOS quality of life, and WOMAC scores in another study [28].

Although the majority of studies that reported return to activity data following TKA found the majority participated in low-impact activities [45], a few described patients who returned to high-impact sports. However, an analysis of symptoms or limitations with these activities has not been rigorously conducted to our knowledge. For instance, Mont et al. [39] followed a cohort of 31 patients (who represented 4% of their TKA population) that returned to sports that involved running and other high-impact activities a mean of 4 years postoperatively. All but one had excellent clinical outcomes and were satisfied with the result of the operation. The authors stressed their opinion that these types of activities were not appropriate for the majority of patients. However, with a small percentage choosing to return, surgeons should work closely to individualize recommendations. Mayr et al. [28] found that 25% of 81 patients who lived in an Alpine area returned to high-impact activities such as downhill skiing and tennis, and 47% returned to medium-impact sports such as mountain hiking and cross-country skiing. All but one patient had been involved in sports during their lifetime. While most patients were participating in low-impact activities at the 1-year evaluation, the evaluation at 6 years showed increased involvement in higher-impact sports. Hepperger et al. [25] reported that 74% of 200 patients from Austria returned to hiking and 70% returned to downhill skiing 2 years postoperatively. These authors attributed the results to living in the Alpine region and noted that the home geographic environment plays an important role in activities resumed postoperatively.

10.4 Objective Measured Physical Activity After TKA

Eight studies measured movement-related activity, three of which determined the percent of patients who achieved AHA recommended PA guidelines (Table 10.4) [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. At 6 months postoperatively, two studies reported that 0% [47] to 18% [46] met the guidelines, and at 12 months postoperatively, one study [48] found that 16.5% met the guidelines. There was wide variability in study conclusions regarding time spent in sedentary behavior compared with preoperative data, as four studies reported no change [47,48,49, 51] and three studies reporting a significant decrease [46, 50, 52]. Postoperative PA levels were considerably lower than those of healthy controls in one study [48] and were lower than previously published data in another study [50].

It is important to note that in normal adult populations, investigators have shown that only a small percentage of adults meet AHA guidelines. Whether the data from TKA studies and those from control populations regarding problems achieving PA guidelines are strictly related to aging or are due to other factors such as socioeconomic status and motivation is unclear and worthy of future study. One investigation that measured PA in 2450 healthy adults aged 70–93 years reported that only 15% of men and 10% of women achieved >150 minutes a week of PA [54]. Another study of 3459 US adults aged 49–85 years measured PA for 7 days and reported that only 2.5% achieved adherence of PA guidelines of ≥30 min/day of moderate-to-vigorous movement intensity [55].

In a systematic review of 26 studies that measured PA levels after total joint (hip and knee) arthroplasty (using either objective instruments or recall questionnaires), Naal and Impellizzeri [56] reported noteworthy heterogeneity and provided recommendations to standardize future studies. They noted patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty were less active than recommended AHA levels. Accelerometers provide realistic data of all types of activity (light, moderate, and vigorous) and give feedback and motivation to patients [57]. Total daily step count is a beneficial motivator, and Garber et al. [58] recommended ≥7000 steps/day, which could be achieved by increasing step counts by ≥2000 as necessary to achieve this level. In 2018, Hammett et al. [59] systematically reviewed the literature for studies that only used accelerometers from preoperative to postoperative from inception of the PubMed database to January 2016 for TKA and total hip arthroscopy. Seven studies were included, four of which focused on TKA, and the authors found no significant increase in PA at 6 months (compared with preoperative) and only a small to moderate effect at 12 months.

Clinical studies usually employ patient self-reporting of activity levels with questionnaires such as the UCLA activity scale [60]. These data are not always reliable, may be subject to recall bias [51, 61], and may overestimate PA compared with objective activity measurements [47, 50, 51]. For example, Harding et al. [47] reported no change in PA parameters 6 months after TKA measured with an accelerometer in 25 patients. However, there was a significant increase in the UCLA activity scores between the preoperative and follow-up evaluations (3 ± 1 and 5 ± 3, respectively; P < 0.001). Brandes et al. [50] also reported no correlation between PA and clinical outcomes as measured with the Knee Society Score and SF-36.

10.5 Recommended Sports and Recreational Activities

At the time of writing, the most recent activity recommendations following TKA by the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons were published in 2009 (Table 10.5) [62]. Based on the results of 139 completed surveys from the 2007 annual meeting, consensus was reached for low-impact activities such as walking, climbing stairs, bicycling on level surfaces, swimming, doubles tennis, and golfing. Activities that were consistently discouraged included jogging, sprinting, skiing on difficult terrain, and singles tennis. A survey of 94 surgeons from the Netherland Orthopaedic Association included 40 sports, of which the surgeons indicated whether they were allowed, allowed with experience, discouraged, or no opinion [63]. The results for patients <65 years of age are shown in Table 10.5. For patients >65 years of age, the same activities achieved consensus for allowed and not allowed as the younger group. Two additional activities reached consensus for allowed with experience (cross-walking and rowing). A systematic review of 21 studies published from 1986 through 2010 by Vogel et al. [64] provided advice regarding the most appropriate activities after TKA. These authors stressed the avoidance of sports that create high-impact loads and noted that rehabilitation may take at least 3 months to allow low-impact activities.

10.6 Authors’ Discussion

Important goals of TKA in younger active patients include maintaining a healthy lifestyle and returning to desired realistic recreational or sports activities. However, in patients who wish to resume moderate- or high-intensity recreational and sports activities after TKA, the high loads placed on the knee joint may result in chronic effusions and muscle dysfunction.

There was a wide range of patients that resumed mostly light, low-impact recreational activities after TKA (25–100%). There are many potential reasons for lack of postoperative participation in recreational activities or PA, including lingering effects of the operation (pain or swelling), the natural aging process, income, educational status, area of residency, personal barriers and beliefs, self-efficacy, and social support [65,66,67,68]. The reasons patients elect not to participate in recreational activities after TKA are important to determine, especially in studies in which return to PA is a main focus. Five studies reported that the factors most commonly responsible for the inability to return to PA were other musculoskeletal problems or persistent pain in the TKA joint [23, 31, 37, 38, 43].

Few studies provided data regarding symptoms or functional limitations that occurred during recreational or sports activities. For patient counseling purposes, future studies should provide these data to ensure that preoperative patient expectations are realistic in terms of activities that are resumed after surgery. Finally, no study provided detail regarding the postoperative rehabilitation program. This book describes in detail the role of the physical therapist in guiding a patient back to recreational or fitness activities. Rehabilitation programs that incorporate strength, balance, flexibility, and neuromuscular function have been recommended to safely resume PA [69,70,71]. Objective assessment of muscular and neuromuscular function prior to release to activities is also recommended [72,73,74,75]. A careful balance of joint loads must be managed to reduce chronic knee joint effusions (which is an indicator of the need to reduce activities) and chronic muscle weakness.

References

Weinstein AM, Rome BN, Reichmann WM, Collins JE, Burbine SA, Thornhill TS, Wright J, Katz JN, Losina E. Estimating the burden of total knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(5):385–92. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.L.00206.

Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the U.S., 2014 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100(17):1455–60. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.17.01617.

Maradit Kremers H, Larson DR, Crowson CS, Kremers WK, Washington RE, Steiner CA, Jiranek WA, Berry DJ. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(17):1386–97. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.N.01141.

Elleuch MH, Guermazi M, Mezghanni M, Ghroubi S, Fki H, Mefteh S, Baklouti S, Sellami S. Knee osteoarthritis in 50 former top-level soccer players: a comparative study. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2008;51(3):174–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annrmp.2008.01.003.

Spector TD, Harris PA, Hart DJ, Cicuttini FM, Nandra D, Etherington J, Wolman RL, Doyle DV. Risk of osteoarthritis associated with long-term weight-bearing sports: a radiologic survey of the hips and knees in female ex-athletes and population controls. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(6):988–95.

Tveit M, Rosengren BE, Nilsson JA, Karlsson MK. Former male elite athletes have a higher prevalence of osteoarthritis and arthroplasty in the hip and knee than expected. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):527–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546511429278.

Granan LP, Bahr R, Lie SA, Engebretsen L. Timing of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructive surgery and risk of cartilage lesions and meniscal tears: a cohort study based on the Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registry. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):955–61. 0363546508330136 [pii]. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546508330136.

Brophy RH, Rai MF, Zhang Z, Torgomyan A, Sandell LJ. Molecular analysis of age and sex-related gene expression in meniscal tears with and without a concomitant anterior cruciate ligament tear. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(5):385–93. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.K.00919.

Mihelic R, Jurdana H, Jotanovic Z, Madjarevic T, Tudor A. Long-term results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison with non-operative treatment with a follow-up of 17–20 years. Int Orthop. 2011;35(7):1093–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-011-1206-x.

Gerhard P, Bolt R, Duck K, Mayer R, Friederich NF, Hirschmann MT. Long-term results of arthroscopically assisted anatomical single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using patellar tendon autograft: are there any predictors for the development of osteoarthritis? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(4):957–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-012-2001-y.

Ahn JH, Kim JG, Wang JH, Jung CH, Lim HC. Long-term results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using bone-patellar tendon-bone: an analysis of the factors affecting the development of osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(8):1114–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.019.

Janssen RP, du Mee AW, van Valkenburg J, Sala HA, Tseng CM. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with 4-strand hamstring autograft and accelerated rehabilitation: a 10-year prospective study on clinical results, knee osteoarthritis and its predictors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(9):1977–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-012-2234-9.

Deakin AH, Smith MA, Wallace DT, Smith EJ, Sarungi M. Fulfilment of preoperative expectations and postoperative patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. A prospective analysis of 200 patients. Knee. 2019;26(6):1403–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2019.07.018.

Jain D, Nguyen LL, Bendich I, Nguyen LL, Lewis CG, Huddleston JI, Duwelius PJ, Feeley BT, Bozic KJ. Higher patient expectations predict higher patient-reported outcomes, but not satisfaction, in total knee arthroplasty patients: a prospective multicenter study. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9S):S166–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.01.008.

Jassim SS, Douglas SL, Haddad FS. Athletic activity after lower limb arthroplasty: a systematic review of current evidence. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(7):923–7. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.96B7.31585.

Lützner C, Postler A, Beyer F, Kirschner S, Lützner J. Fulfillment of expectations influence patient satisfaction 5 years after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(7):2061–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-5320-9.

Husain A, Lee GC. Establishing realistic patient expectations following total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(12):707–13. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00049.

Barber-Westin SD, Noyes FR. Aerobic physical fitness and recreational sports participation after total knee arthroplasty. Sports Health. 2016;8(6):553–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738116670090.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, George SM, Olson RD. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020–8.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP. Physical activity guidelines for Americans from the US department of health and human services: cardiovascular benefits and recommendations. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(11):e005263.

DiPietro L, Buchner DM, Marquez DX, Pate RR, Pescatello LS, Whitt-Glover MC. New scientific basis for the 2018 US Physical Activity Guidelines. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8(3):197.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2018 physical activity guidelines advisory committee scientific report. Washington, DC; 2018.

Naylor JM, Pocovi N, Descallar J, Mills KA. Participation in regular physical activity after total knee or hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: prevalence, associated factors, and type. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71(2):207–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23604.

Rocha Da Silva R, Filardi De Oliveira P, Almeida Matos M. Sports activity after total knee arthroplasty. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2018;20(2):133–8. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0012.0423.

Hepperger C, Gfoller P, Abermann E, Hoser C, Ulmer H, Herbst E, Fink C. Sports activity is maintained or increased following total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(5):1515–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-017-4529-3.

Vielgut I, Leitner L, Kastner N, Radl R, Leithner A, Sadoghi P. Sports activity after low-contact-stress total knee arthroplasty - a long term follow-up study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24630. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24630.

Bercovy M, Langlois J, Beldame J, Lefebvre B. Functional results of the ROCC(R) mobile bearing knee. 602 cases at midterm follow-up (5 to 14 years). J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(6):973–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2015.01.003.

Mayr HO, Reinhold M, Bernstein A, Suedkamp NP, Stoehr A. Sports activity following total knee arthroplasty in patients older than 60 years. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(1):46–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2014.08.021.

Chang MJ, Kim SH, Kang YG, Chang CB, Kim TK. Activity levels and participation in physical activities by Korean patients following total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:240. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-240.

Long WJ, Bryce CD, Hollenbeak CS, Benner RW, Scott WN. Total knee replacement in young, active patients: long-term follow-up and functional outcome: a concise follow-up of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(18):e159. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.M.01259.

Argenson JN, Parratte S, Ashour A, Saintmard B, Aubaniac JM. The outcome of rotating-platform total knee arthroplasty with cement at a minimum of ten years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(7):638–44. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.K.00263.

Jones DL, Bhanegaonkar AJ, Billings AA, Kriska AM, Irrgang JJ, Crossett LS, Kwoh CK. Differences between actual and expected leisure activities after total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1289–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2011.10.030.

Kersten RF, Stevens M, van Raay JJ, Bulstra SK, van den Akker-Scheek I. Habitual physical activity after total knee replacement. Phys Ther. 2012;92(9):1109–16. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20110273.

Meding JB, Meding LK, Ritter MA, Keating EM. Pain relief and functional improvement remain 20 years after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):144–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-2123-4.

Bonnin M, Laurent JR, Parratte S, Zadegan F, Badet R, Bissery A. Can patients really do sport after TKA? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(7):853–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-009-1009-4.

Jackson JD, Smith J, Shah JP, Wisniewski SJ, Dahm DL. Golf after total knee arthroplasty: do patients return to walking the course? Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2201–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546509339009.

Dahm DL, Barnes SA, Harrington JR, Sayeed SA, Berry DJ. Patient-reported activity level after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(3):401–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.051.

Hopper GP, Leach WJ. Participation in sporting activities following knee replacement: total versus unicompartmental. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(10):973–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-008-0596-9.

Mont MA, Marker DR, Seyler TM, Jones LC, Kolisek FR, Hungerford DS. High-impact sports after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(6 Suppl 1):80–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.018.

Mont MA, Marker DR, Seyler TM, Gordon N, Hungerford DS, Jones LC. Knee arthroplasties have similar results in high- and low-activity patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:165–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/BLO.0b013e318042b5e7.

Walton NP, Jahromi I, Lewis PL, Dobson PJ, Angel KR, Campbell DG. Patient-perceived outcomes and return to sport and work: TKA versus mini-incision unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2006;19(2):112–6.

Chatterji U, Ashworth MJ, Lewis PL, Dobson PJ. Effect of total knee arthroplasty on recreational and sporting activity. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(6):405–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03400.x.

Huch K, Muller KA, Sturmer T, Brenner H, Puhl W, Gunther KP. Sports activities 5 years after total knee or hip arthroplasty: the Ulm Osteoarthritis Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(12):1715–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2004.033266.

Argenson JN, Parratte S, Ashour A, Komistek RD, Scuderi GR. Patient-reported outcome correlates with knee function after a single-design mobile-bearing TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(11):2669–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0418-x.

Hanreich C, Martelanz L, Koller U, Windhager R, Waldstein W. Sport and physical activity following primary total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(8):2274–2285.e2271. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ARTH.2020.04.013.

Frimpong E, McVeigh JA, van der Jagt D, Mokete L, Kaoje YS, Tikly M, Meiring RM. Light intensity physical activity increases and sedentary behavior decreases following total knee arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27(7):2196–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-4987-2.

Harding P, Holland AE, Delany C, Hinman RS. Do activity levels increase after total hip and knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1502–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-3427-3.

Lutzner C, Kirschner S, Lutzner J. Patient activity after TKA depends on patient-specific parameters. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(12):3933–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3813-5.

Vissers MM, Bussmann JB, de Groot IB, Verhaar JA, Reijman M. Physical functioning four years after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Gait Posture. 2013;38(2):310–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2012.12.007.

Brandes M, Ringling M, Winter C, Hillmann A, Rosenbaum D. Changes in physical activity and health-related quality of life during the first year after total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(3):328–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20384.

de Groot IB, Bussmann HJ, Stam HJ, Verhaar JA. Small increase of actual physical activity 6 months after total hip or knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(9):2201–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-008-0315-3.

Walker DJ, Heslop PS, Chandler C, Pinder IM. Measured ambulation and self-reported health status following total joint replacement for the osteoarthritic knee. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(7):755–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/41.7.755.

Hoorntje A, Witjes S, Kuijer P, Bussmann JBJ, Horemans HLD, Kerkhoffs G, van Geenen RCI, Koenraadt KLM. Does activity-based rehabilitation with goal attainment scaling increase physical activity among younger knee arthroplasty patients? Results from the randomized controlled ACTION trial. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(3):706–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2019.10.028.

Jefferis BJ, Sartini C, Lee IM, Choi M, Amuzu A, Gutierrez C, Casas JP, Ash S, Lennnon LT, Wannamethee SG, Whincup PH. Adherence to physical activity guidelines in older adults, using objectively measured physical activity in a population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:382. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-382.

Berkemeyer K, Wijndaele K, White T, Cooper A, Luben R, Westgate K, Griffin S, Khaw K-T, Wareham N, Brage S. The descriptive epidemiology of accelerometer-measured physical activity in older adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):2.

Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM. How active are patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty?: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(7):1891–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-009-1135-9.

Sparling PB, Howard BJ, Dunstan DW, Owen N. Recommendations for physical activity in older adults. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;350:h100. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h100.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, Nieman DC, Swain DP. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334–59. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb.

Hammett T, Simonian A, Austin M, Butler R, Allen KD, Ledbetter L, Goode AP. Changes in physical activity after total hip or knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of six- and twelve-month outcomes. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70(6):892–901. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23415.

Zahiri CA, Schmalzried TP, Szuszczewicz ES, Amstutz HC. Assessing activity in joint replacement patients. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(8):890–5.

Welk GJ, Kim Y, Stanfill B, Osthus DA, Calabro MA, Nusser SM, Carriquiry A. Validity of 24-h physical activity recall: physical activity measurement survey. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(10):2014–24. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000314.

Swanson EA, Schmalzried TP, Dorey FJ. Activity recommendations after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a survey of the American Association for Hip and Knee Surgeons. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 Suppl):120–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2009.05.014.

Meester SB, Wagenmakers R, van den Akker-Scheek I, Stevens M. Sport advice given by Dutch orthopaedic surgeons to patients after a total hip arthroplasty or total knee arthroplasty. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202494.

Vogel LA, Carotenuto G, Basti JJ, Levine WN. Physical activity after total joint arthroplasty. Sports Health. 2011;3(5):441–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738111415826.

Crombie IK, Irvine L, Williams B, McGinnis AR, Slane PW, Alder EM, McMurdo ME. Why older people do not participate in leisure time physical activity: a survey of activity levels, beliefs and deterrents. Age Ageing. 2004;33(3):287–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh089.

Li F, Harmer PA, Cardinal BJ, Bosworth M, Acock A, Johnson-Shelton D, Moore JM. Built environment, adiposity, and physical activity in adults aged 50–75. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.021.

Parks SE, Housemann RA, Brownson RC. Differential correlates of physical activity in urban and rural adults of various socioeconomic backgrounds in the United States. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(1):29–35.

Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(12):1996–2001. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000038974.76900.92.

Meier W, Mizner RL, Marcus RL, Dibble LE, Peters C, Lastayo PC. Total knee arthroplasty: muscle impairments, functional limitations, and recommended rehabilitation approaches. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(5):246–56. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2008.2715.

Mistry JB, Elmallah RD, Bhave A, Chughtai M, Cherian JJ, McGinn T, Harwin SF, Mont MA. Rehabilitative guidelines after total knee arthroplasty: a review. J Knee Surg. 2016;29(3):201–17. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1579670.

Piva SR, Teixeira PE, Almeida GJ, Gil AB, DiGioia AM 3rd, Levison TJ, Fitzgerald GK. Contribution of hip abductor strength to physical function in patients with total knee arthroplasty. Phys Ther. 2011;91(2):225–33. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20100122.

Marmon AR, McClelland JA, Stevens-Lapsley J, Snyder-Mackler L. Single-step test for unilateral limb ability following total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(2):66–73. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2013.4372.

Marmon AR, Milcarek BI, Snyder-Mackler L. Associations between knee extensor power and functional performance in patients after total knee arthroplasty and normal controls without knee pain. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014;9(2):168–78.

Ko V, Naylor JM, Harris IA, Crosbie J, Yeo AE. The six-minute walk test is an excellent predictor of functional ambulation after total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:145. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-145.

Boonstra MC, De Waal Malefijt MC, Verdonschot N. How to quantify knee function after total knee arthroplasty? Knee. 2008;15(5):390–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2008.05.006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barber-Westin, S., Noyes, F.R. (2022). Recommended Guidelines for Physical Activity and Athletics After Knee Arthroplasty. In: Noyes, F.R., Barber-Westin, S. (eds) Critical Rehabilitation for Partial and Total Knee Arthroplasty. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87003-4_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87003-4_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-87002-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-87003-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)