Abstract

Current trends in the assessment of language difficulties and disorders in bilingual children are often unaware of differences between the standard variety and the (emergence of) a dialect in heritage languages. This chapter aims at filling this gap by focusing on the specific bilectal situation of Immigrant Turkish (IT) in Germany. It reports further on a study that tested the performance of 52 typically developing Turkish L1 heritage children (5;0–12;4) in a sentence repetition task (SRT). SRTs are a testing format previously known as being stable against language change and are reliably assessing developmental language disorders. Our study sheds light on the (non-)applicability of SRTs for bilectal speakers, since IT dialect features result in inaccurate repetitions. Given that IT, and not the standard Turkish variety, is the major source of language input for Turkish children in Germany, misdiagnoses are possible. Our results strengthen previous findings from other bilectal contects, such as Cypriot Greece. However, IT Speakers are a unique subgroup of Bilectals, since most Turkish children in Germany lack access to a “high” L1-variety (Rowe and Grohmann, Int J Sociol Lang 224:119–142, 2013). We discuss that bilectal challenge should have an impact on the construction, the scoring, and the outcome of Turkish standardized language tests.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 The Immigrant Turkish Dialect as a Heritage Language in Germany

Germany has always been a country with several bilectal and diglossic contexts (Rash, 2002; Földes, 2005; Koneva & Gural, 2015). In the last decades, dialect use is continuously decreasing, whereas the empowerment and the legal and societal acceptance of minority languages and their speakers, such as “Low German (Plattdeutsch)”, “Lower Sorbian”, or Danish, increases.

Despite Germany’s long history of immigration and experience with heritage speaking and refugee children in the educational system, the languages of migrant communities, such as Turkish, Russian, Kurdish, Syrian Arabic or Bosnian, however, are not addressed with the status of minority languages legally, even though most citizens in Germany acquire one or more of these languages additionally to German. In 2018, 64% of families with children under 18 years of age had a migrant background (Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2018). The number of children speaking more than only German oral language at home increases constantly (Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2018), leading to an increase of heritage language speakers (i.e. Fishman, 2001; Gagarina, 2014).

Turkish is spoken in Europe and other countries, and since the 1960s, many states in Western Europe host large Turkish immigrant communities (e.g. Backus et al., 2010). Importantly, language loss is remarkably rare in the Turkish communities, since immigration is a continuous process. Today, Germany has the biggest Turkish-origin population in Western Europe. An estimated population of 4 million people, of full or partial Turkish origin live in the country (Feltes et al., 2013: 93); that is approximately 5% of Germany's total population of 82 million inhabitants.

Note, however, that, even after four generations Turkish-origin minority populations, people with a Turkish background tend to occupy the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum, as it is not untypical of immigrant communities with roots in labour migration (cf. Backus, 2010; Riphahn et al., 2010). In 2010, Immigrants of Turkish origin were least successful in the German labour market, 30% of adolescents did not finish school, many were jobless, and only one third of Turkish women in Germany were employed. The Turkish communities often live in city centres, and, in cities like Berlin, Hamburg or Mannheim, where seem to be city quarters almost exclusively populated by people of Turkish origin.

The German school system and the educational policies in the Federal Countries of Germany, however, hold specific obstacles for students with a heritage language background. The segregated system of schooling leading to the early tracking of children into higher and lower types of secondary education is particularly disadvantageous for children who grow up speaking non-standard varieties of the majority language, and local dialects, ethnolects, some youth style, or a mixture of these (i.e. Backus, 2010). Moreover, national education reports continuously state the additional disadvantage of children from families with a low socioeconomic status and a history of migration (“migrant background”) (i.e. Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung, 2016, 2018). Such children need more time for acquiring the standard academic variety of the language (“Bildungssprache”). This is – alongside the stereotypes of teachers against the performance of children with a migrant background (Berliner Institut für empirische Integrations- und Migrationsforschung, 2017) – the most relevant drawback on school attainment (i.e. Gogolin, 1994). In spite of the efforts of many scholars in educational science to establish translanguaging as method of teaching and language education already in the 1990s (i.e. Gogolin, 1994), knowledge of the German language is considered a necessary condition for academic and later professional success.

Turkish as a heritage language in Germany, however, is a peculiar case of language acquisition in a bilectal situation. The term heritage language defines the first/family language of minority language children in Germany, being “languages spoken by the children of immigrants or by those who immigrated to a country when young” (Cho et al., 2004: 23). Children acquire the heritage language particularly at home and among the extended family. Exposure to the societally dominant (majority) language may start in the family, but it is more dominant outside home, and especially at school (Polinsky, 2018). The heritage (language) speakers can be successive or simultaneous bilinguals (Bennamoun et al., 2013). A heritage language is acquired incompletely, since the individual uses another (i.e. the majority) language. Secondly, heritage language implies a continuity of proficiencies, reflecting the heterogeneity in heritage language proficiencies observed by several researchers (see Polinsky & Kagan, 2007). Considering linguistic characteristics in detail, there is systematic change in the heritage language of young adults, e.g., of third/fourth generation immigrants. If compared to the standard variety of the L1, the heritage varieties of the L1 show, for example, reduced morphological and syntactic structures (Valdés, 2000; Fishman, 2001; Cummins, 2005; Polinsky & Kagan, 2007; Montrul et al., 2010). At the same time, heritage language speakers seem to have advantages in pronunciation, phonology and spontaneous speech production in comparison to the learners of the second language (Au et al., 2002; Montrul et al., 2008). The reduced input and effects of the second on the first language (Cook, 2003) can result in incomplete acquisition or language attrition (Montrul, 2009; Rothmann, 2009).

Monolingual Turkish speakers immigrated to Germany with the first generation of migrant workers from the 1960s. Importantly, the German labour market recruited people with little education and supported the intention to return to Turkey after a few years, hardly offering opportunities for learning the majority language. Recent generations, as children under the age of 3–4, might be monolingual speakers of Turkish, as immigration continues and the community members actively chose Turkish as family language at home. However, self- reported survey data in France and Germany show that many families use the national languages increasingly alongside Turkish (Akıncı, 2008; Akıncı et al., 2013). Intra-community variation in language use and family language practice is a relevant factor for sociolinguistic research and language assessment in children with Turkish heritage language in Germany. Even though the ethnolinguistic vitality of Turkish is documented (Yagmur & Akinci, 2003; Extra & Yağmur, 2004), it has to be stated that heritage language acquisition often reduces to the spoken language variety of Turkish. The family language use is mostly restricted to the oral varieties, and literacy or academic use of Turkish is limited to some children participating in secondary education (i.e. Turkish as a subject in secondary schools in Hamburg) or (private) afternoon classes, but the general development in the last decade has been toward the abolition of forms of bilingual education. Though contexts for writing in Turkish exist, the degree to which Turks in Western Europe are used to writing in Turkish varies enormously. Consequently, studies of the written Turkish of the immigrant communities has increased only recently (but see Schroeder, 2007; Akıncı, 2008; Dirim, 2009; Akıncı et al., 2013). Moreover, Schroeder (2009) illustrates that Turkish language education in German schools aims at teaching the written language in a very norm-orientated way, emphasising a dichotomy between the standard variety of “anadil” (mother tongue) on the one and “Türkçemiz” (our Turkish) on the other hand.

The notion of the cultural and linguistic differentiation between the standard (written) and the spoken language is of grave importance for heritage language acquisition in Germany, since the Turkish used in Germany is subject to language change, resulting in a new dialect. Large- scale research projects in France, the Netherlands and Germany compared samples of immigrant speech or texts and samples of speech collected in the regions in Turkey from which the original immigrants came (i.e. Doğruöz & Backus, 2007, 2009; Pfaff, 1991; Rehbein, 2001; Herkenrath et al., 2003; Rehbein & Karakoç, 2004; Baumgarten et al., 2007; Herkenrath, 2007; Karakoç, 2007; Banaz, 2002; Johanson, 2002; Uzuntaş, 2008; Şimşek & Schroeder, 2011; Schellhardt & Schroeder, 2013; Schroeder & Dollnick, 2013). They focused on the changes of spoken varietes of Turkish grammar and written language competencies of bilingual children with Turkish as their heritage language.

The changes to Turkish are systematic, and were defined by Johanson as a New Variety of Turkish. The “Immigrant Turkish” dialect (Backus, 2004) differs from Standard Turkish in several aspects (cf. examples below). Importantly, these changes are not entirely based on language contact phenomena, such as cross-linguistic influence in the lexical domain that leads to almost literal translation of multiword units in the majority language. Importantly, “Immigrant Turkish” as a branching term conceals the specific language-induced contact phenomena in different countries as well as the influence of migrant waves, leading to unique ways of dialect levelling. Syntactic variation, for example, between the Turkey-Turkish norms and the Immigrant Turkish dialect were very few in the Netherlands. Neither were entire subsystems, nor were constructions especially sensitive to Dutch influence, that is <1% of “unconventional” structures (Doğruöz & Backus, 2009).

In Germany, however, the Hamburg project focused on structures above clause level, such as subordination, discourse connectivity, and discourse marking in retelling the Snow White fairy tale. Several differences between Immigrant Turkish dialect (IT) and the data from Turkey were different use of finite verb inflection, the use of a smaller range of forms, limitations to one tense marking in narratives (substitution of the evidential form of –mIş, Pfaff, 1994), and the overuse of deictic temporal adverbs in retelling. While monolingual Turkish children acquire both complement and relative clauses at the age of approximately 5 years or older (Aksu-Koç, 1994), Turkish-German bilingual children between the ages of 4 and 9 prefer finite clauses over subordination. Deviations between the standard variety of Turkish in Turkey and the Immigrant Turkish dialect are especially found in the avoidance of using “complex structures” simple juxtaposition instead of complex structures (Sarı, 2006; Treffers-Daller et al., 2006; Dollnick, 2013; Herkenrath, 2014; Bayram, 2013; Onar Valk, 2015; Schroeder, 2016) (cf. example 1). It has also been reported for Immigrant Turkish dialect speakers that they interchange dative and accusative, and use unconventional forms of plural markings (“iki adamlar” instead of “iki adam” in the standard variety).

(1) | Finite instead of non-finite clauses | ||||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | |||||

Çocuk | sineği | vurmak | istiyor. | ||

Child | fly-ACC | hit-INF | want-PROG-3SG | ||

Babası | diyor | ||||

Father- POSS-3SG | say-PROG-3SG | ||||

“Hayır, yapma!” | (Treffers-Daller et al., 2006) | ||||

no | do-IMP-NEG-2SG | ||||

Standard Turkish: | |||||

Çocuk sineği | vurmak | istiyor. | |||

Child | fly-ACC | hit-INF | want-PROG-3SG | ||

Babası | da | yapmamasını | söylüyor. | ||

Father-POSS-3SG | so | do-NEG-NOM-POSS-3SG-ACC | tell-PROG-3SG | ||

‘The child then wants to catch it with a cloth. And his father tells him not to do (that).’ | |||||

Further characteristics of the IT dialect refer to the omission/substitution of genitive markings in modal constructions (Menz, 1991), compounds (Aytemiz, 1990), and with subjects in nominalised subordinated sentences (Sarı, 1995). IT speakers also tend to overuse pronominal subjects and objects (Aytemiz, 1990; Menz, 1991; Pfaff, 1991; Rehbein, 2001). Besides, bilingual speakers and bilingual children acquiring the Immigrant Turkish dialect as heritage language use the general all-purpose verb yapmak extensively by adding it to the German verb stem or the Turkish infinitive form and to avoid the standard progressive form (Boeschoten, 1994) (cf. example 2).

(2) | General All-Purpose Verb yapmak: | |||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | ||||

Ondan sonra ödevim | bitmediyse, | |||

Later | homework-POSS-1SG | finish-NEG-PAST-COND | ||

onu | devam | yapıyorum | (Boeschoten, 1994) | |

it-ACC | continuance | make-PROG-1SG | ||

Standard Turkish: | ||||

Ondan sonra | ödevim | bitmediyse, | ||

Later | homework-POSS-1SG | finish-NEG-PAST-COND | ||

ona | devam ediyorum. | |||

It-DAT | continue-PROG-1SG | |||

‘Then if my homework hasn’t been finished, I go on with it.’ | ||||

Moreover, it is not only the German/Turkish contact situation, but also the origin of the first- and second-generation immigrants that features IT as a distinct spoken dialect. Dialect levelling, i.e. levelling of Anatolian dialects spoken especially by the first generation of immigrants (Boeschoten & Broeder, 1999; Schroeder & Stölting, 2005), is a typical feature of IT in Germany. It arises in, for example, an overuse of ablative forms in locative contexts (cf. example 3), or an omission of interrogative particles in yes-no questions (cf. example 4).

(3) | Overextension of the ablative case | |||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | ||||

Savaştan | rüya | gördüm. | (Backus & Boeschoten, 1998) | |

War-ABL | dream | see-PAST-1SG | ||

Standard Turkish: | ||||

Rüyamda | savaş gördüm. | |||

my dream-LOC | war | see-PAST-1SG | ||

‘I dreamed about the war.’ | ||||

(4) | Omission of interrogative particle in yes-no questions | |||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | ||||

Bugün okulda | oynadıın? | (Hess & Gabriel, 1979) | ||

Today | school-LOC | play-PAST-2SG-Ø | ||

Standard Turkish: | ||||

Bugün okulda | oynadın | mı? | ||

Today school-LOC | play-PAST-2SG | INT | ||

‘Did you play at school today?’ | ||||

Since the previous examples are documented for the variety of IT over 20 years ago, the current study used the data from the MULTILIT study (Schellhardt and Schroeder 2015) to test the actuality of these IT features for contemporary learners of IT in Germany. The MULTILIT corpus contains oral and written data from bilingual children with Turkish heritage language in Germany and France. The analyses of the MULTILIT data confirm the status of IT as a dialect that shapes the heritage language (L1) input of bilingual Turkish-German children. The characteristics of the Immigrant Turkish dialect consist of dialect-levelling features from East- Anatolia. Boeschoten (2000), and Şimşek and Schroeder (2011) illustrate such features with the the instrumental case suffix: While the standard form is (y)la / (y)le, a different form, len / lan, is typically for the spoken Turkish in Western Europe. Further, dialectal variations on the lexical level, like the use of değmek (touch) instead of çarpmak (hit) (cf. example 5). The omission of genitive markers and other indications of morphological changes and loss (cf. example 6), (Boeshoten, 2000) are revealed. Other phenomena, such as the use of reflexive pronoun kendi- as a focus marker (Schroeder, 2014) or unconventional plural marking (i.e. an increased use of plural markers as language-contact phenomenon between German and Turkish, Johanson, 1993: 214) are documented (cf. example 7).

(5) | Dialect levelling and code-switching | ||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | |||

Kafanlan | Stuhle | değiyon. (OGU; 5th grade; 11–12 years old) | |

Head-POSS-2SG-INS | chair-GER-DAT | DIALECT- touch-2SG | |

Standard Turkish: | |||

Kafanı | sandalyeye çarpıyorsun. | ||

Head-2SG-ACC | chair-DAT | hit-PROG-2SG | |

‘You hit your head on a chair.’ | |||

(6) | Omission of genitive-possessive markers, kendi- as focus marker and use of locative postposition | |||||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | ||||||

Burada | bir | kız | kendi | sınıfın | içinde | |

Here | INDEF | girl-Ø | self | class-ACC-Ø | inside-POSS-3SG-LOC | |

dışlanmasıdır. | (YON, 12th grade, 17 years old) | |||||

exclude-PASS-VN-2SG-GM | ||||||

Standard Turkish: | ||||||

Burada (olan) | bir | kızın | sınıfta | dışlanmasıdır. | ||

Here (AUX-PART) | INDEF | girl-GEN | class-LOC | exclude-PASS-VN-2SG-GM | ||

‘What happens here is the exclusion of a girl in her own class.’ | ||||||

(7) | Unconventional plural marking | ||||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | |||||

Üç | kızlar | gine | gittiler. | (ILH; 5th grade, 11–12 years old) | |

Three | girl-PL | again | go-PAST-3PL | ||

Standard Turkish: | |||||

Üç kız yine gitti. | |||||

Three girl again go-PAST-3SG | |||||

‘Three girls went again.’ | |||||

To summarise the results on the Immigrant Turkish dialect in Germany so far, show that IT is a “catalyst” dialect (Rehbein et al., 2009), which may cause bilingual Turkish speakers either to develop new forms or to use existing ones in ways that differ from the Turkish used in Turkey. Thus, the heritage language input of bilingual Turkish-German children is a dialectal one. The bilectal problem is evident with respect to the heterogeneity of the Turkish speaking community (Johanson, 1991; Chilla et al., 2013). In contrast to other bilectal contexts, such as Cypriot Greek, IT dialect children in Germany have only limited access to a “high” variety (Rowe & Grohmann, 2013; Kambanaros et al., 2013) of Turkish. The “discrete bilectalism” of “low variety” IT in Germany is unique, since Turkish children lack a formal register as well as a general access to formal education (i.e. in preschool) and literacy education for standard Turkish in Germany (Küppers et al., 2015).

2 The Assessment of Developmental Language Disorder in Bilingual Contexts

It is alleged that Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) appears with a prevalence rate of approximately 8% (Norbury et al., 2016). Hence, it is very common in children, especially if compared to genetic syndromes, for example. Research further indicates that DLD is a life-long condition characterised by difficulties with understanding and/or using spoken language and is likely a result of a number of biological, genetic and environmental risk factors (Bishop et al., 2016, 2017). Following the CATALISE recommendations, the term “DLD” is used for children whose language disorder does not occur with another biomedical condition, such as a genetic syndrome, a sensorineural hearing loss, neurological disease, Autism Spectrum Disorder or Intellectual Disability (cf. Stothard et al., 1998; Johnson et al., 1999; Tomblin, 2010). For epigenetic studies, Tomblin et al. (2008) proposed the EpiSLI criterion, based on five composite scores representing performance in three domains of language (vocabulary, grammar, and narration) and two modalities (comprehension and production). Children scoring in the lowest 10% on two or more composite scores are identified as having language disorder. Furthermore, Lancaster and Camerata (2019) point out that DLD should be seen as a spectrum condition.

2.1 DLD in Bilinguales and Bilectals

Given the heterogeneity of DLD, language assessment is generally difficult even to the point that clinically interpretable subtypes are unlikely (Lancaster & Caramerata, 2019). With respect to bilingual acquisition, evidence is clear that children acquiring a second language (L2) in childhood differ from monolingual age-matched peers in several aspects. In the area of morphosyntax, for example, certain linguistic patterns deviating from those of typically developing monolingual children are reported for children acquiring their second language, i.e. German or French (Hamann et al., 2013; Marinis & Armon-Lotem, 2015; Tuller et al., 2018). These distinctive patterns often overlap with those known for monolingual children with Developmental Language Disorders (Paradis, 2010). DLD is common among monolinguals and bilinguals (Leonard, 2010; Engel de Abreu et al., 2013). Therefore, DLD and bilingualism are challenging for research and practice to disentangle DLD specific patterns from L2 interlanguage phenomena. Thus, typically developing bilingual children (BiTD) may be misdiagnosed as having DLD. Several studies focusing on different languages have nonetheless shown that the quality and the quantity of errors differ in BiTD and monolingual children with DLD (MoDLD) (e.g. Paradis et al., 2008; Armon-Lotem, 2014; Meir et al., 2016; Tuller et al., 2018). Since DLD should affect all languages of an individual, it was proposed that the assessment of language disorder must respect both the child´s languages to avoid misdiagnosis.

The typical first language acquisition of Turkish has been in the focus of research for several years now (e.g. Aksu-Koç & Slobin, 1985). Moreover, knowledge on the delayed or disordered acquisition of Turkish, such as different forms of language impairment, phonological disorders, among others, increases constantly (Topbaş, 1997, 1999, 2005, 2007; Babur et al., 2007; Uzuntaş, 2008; Topbaş & Güven, 2008; De Jong et al., 2010; Rothweiler et al., 2010; Topbaş & Yavaş, 2010; Acarlar & Johnston, 2011, among others). These findings lead to the conceptualization and establishment of standard tests for DLD in Turkish (i.e. TELD-3: T, Topbaş & Güven, 2011; see Chapter 3.2 for more details; TİFALDİ, Kazak-Berument & Güven, 2010; T-SALT; Acarlar et al., 2006). Within the COST IS0804 action, Thordardottir (2015), for example, argues for the applicability of standardized assessment tools with a bilingual benefit to Z-scores for simultaneous bilinguals. In the same wake of the COST Action, cross-linguistically valid tools known as the LITMUS tasks (Language Impairment Testing in Multilingual Settings, Armon-Lotem et al., 2015), were developed, also for children with Turkish as heritage language, such as the Multilingual Assessment Tool for Narratives such as MAIN (Gagarina et al., 2012). Those LITMUS tasks aim at identifying Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) in bilingual populations.

2.2 The Assessment of Developmental Language Disorder with Sentence Repetition Tasks

Sentence repetition tasks (SRTs) are widely recognized as tools for the identification of specific language impairment in monolingual and bilingual children (Conti-Ramsden et al., 2001; Vinther, 2002; Klem et al., 2015). SRTs contain of fixed sentences that the participant repeats and thus generate a restricted set of obligatory contexts. They are subtests of most language testing materials and standardized tests for decades, since they are easy to use in clinical settings and have been shown to assess underlying grammatical representations (Polišenská & Kalpaková, 2014) as well as language processing (Archibald & Gathercole, 2006). In addition, evidence shows their applicability in bilingual contexts for distinguishing bilingual children with and without DLD (Meir et al., 2016; de Almeida et al., 2017; Hamann & Abed Ibrahim, 2017). SRTs have been argued to be more reliable than other language-dependent expressive and receptive language tasks, such as (for English) third person singular or past tense tasks for the assessment of DLD (Stothard et al., 1998; Conti-Ramsden et al., 2001). Note, however, that SRTs differ in their conceptualization. The German and the French versions of the LITMUS SRT, for example, focus on morpho-syntactic knowledge, and knowledge of computationally complex structures in particular (Hamann et al., 2013; Marinis & Armon-Lotem, 2015; Fleckstein et al., 2018).

For speech and language practice, SRTs combine several advantages over other testing materials: They aim at grammatical knowledge, are simple and fast to administer and easy to score (identical repetition yes/no). Moreover, they proved to have reasonable to good diagnostic accuracy for children with or without DLD in several language pairs, such as, for example, Turkish-German, Arabic-French, or Portuguese-German children (Hamann & Abed Ibrahim, 2017; Abed Ibrahim & Fekete, 2019; Chilla et al., in press; Hamann et al., in press). As Marinis et al. (2017) point out, LITMUS SR tasks can tease apart BiTD from MoDLD and from BiDLD in several countries and for several language combinations.

Thus, the use of SRTs qualifies as a promising pathway for the assessment of DLD in bilingual populations. Consequently, the use of L1 assessment tools in heritage language contexts, and especially monolingual SRT tasks as a measure for grammatical development is nowadays common practice in research and speech and language assessment. Ertanir et al. (2018), for example, use the SRT subtask of the TELD-3: T (Topbaş & Güven, 2011; see Chapter 3.2 for more details) for the assessment of Turkish kindergarten children in Germany. Their results strengthen the impression that mean performance level in Turkish grammar was below the norming sample mean. The authors argue that bilingual heritage language children show lower L1 grammar skills, if their performance was evaluated with a sentence repetition task. Ertanir et al. (2018) conclude that their results are in line with earlier research observing lower language levels in L1 and L2 (e.g., Caspar & Leyendecker, 2011; Akoğlu & Yağmur, 2016), although the sample in their study consisted of children with well-developed vocabulary skills in their L1, even when compared with monolingual norms.

It is at this point that this study hopes to contribute. Current trends in the assessment of language difficulties and disorders in bilingual children are often unaware of differences between the standard variety and the (emergence of) a dialect in heritage languages. This study aims at filling this gap by focusing on one of the most frequent first languages in Germany, Turkish, showing that the Immigrant Turkish dialect is the major heritage language (L1) input for Turkish-German children. We hypothesize that the bilectal situation of the Immigrant Turkish dialect has an impact on the individual performance of bilingual heritage language children with Turkish as L1 even for sentence repetition tasks. We will show that the appreciation of the Immigrant Turkish spoken dialect has indeed an impact on the construction, scoring, and outcome of standardized language tests. Thus, the study sheds light on the (non-)applicability of SRTs for bilingual children acquiring this specific dialect variety of the standard language Turkish as a minority language in western European countries.

3 The Immigrant Turkish Dialect as a Test Case for Standardized Assessment Tools in Bilectal Contexts

3.1 Participants, Materials and Methods

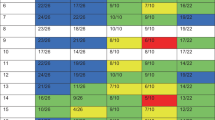

In our BiliSAT and BiLaD projects (see below), data of 61 Turkish-German and Turkish-French children, 52 bilingual typically developing (BiTD), and 9 children with DLD (BiDLD), was gathered. Both projects established the clinical status of the bilingual participants by applying standardized tests in both languages of a child and regarding a “child with DLD” if she scored below adjusted norms in two language domains in each of the languages (cf. Tuller et al., 2018). All participants were tested with a broad assessment procedure (cf. Hamann et al., sub.), including standardized tests in the L1 and L2 (Hamann & Abed Ibrahim, 2017; Tuller et al., 2018; Chilla et al., in press), respecting dominance effects on test performance. Adjustment of monolingual norms was performed following Thordardottir’s (2015) recommendations and by carefully establishing language dominance. Relevant background information was collected with the Questionnaire for Parents of Bilingual Children (PaBiQ; Tuller, 2015).

The analysis here is based on the data subset of 52 typically developing Turkish-German children (age range 5;0-12;4, with 32 boys and 20 girls). 52 SRT subtests from TELD-3: T (Topbaş & Güven, 2011) are taken into account. The TELD-3: T is a norm-referenced test for the Turkish competence of children and an adaptation of the English language assessment tool TELD-3 (Hresko et al., 1991). It includes receptive and expressive language performance in children (2;0- 7;11), using two forms (Form A and Form B). The test aims at identifying a child’s strengths and weaknesses in different language areas as morphology, syntax and semantics and is suitable for the assessment of language delays. Scoring covers expressive, receptive, and global language performance, the latter being a composite value.

Further SRT data was taken from 21 data sets of the TÖDIL (Topbaş & Güven, 2017) sentence repetition subtask. The TÖDIL is an adaptation of the English language assessment tool “Test of Language Development-Primary: Fourth Edition” (TOLD-P:4; Hammill & Newcomer 2008), being a norm-referenced and standardized test for the Turkish competence of children between 4;0-8;11. It intends to provide professionals with a measure for examining receptive, expressive, and organizational language skills and comprises of nine sub-tests such as picture vocabulary, syntactic understanding, sentence repetition, morphological completion, grammar and phonology skills. They include three measures each for listening and speaking abilities.. The combination of all nine sub-tests claims to cover general spoken language abilities. Only children without a risk for DLD and who scored above percentile rank 9 (IQ score ≥ 80 according to Wechsler’s IQ scale) were included in the current study.

3.2 Analysis

Both standardized tests were administered as per description. The children’s responses on the TELD 3: T and the TÖDIL were recorded using special dictaphones. Data transcription, verification and coding for errors were done offline by two independent linguistically trained raters (percentage of agreement was at least 90%). For each repetition measure, the percentage of correct responses was used as basis for data analysis (cf. also Abed Ibrahim & Fekete, 2019). The scoring procedure followed the test handbook, with 1/0 for correct/incorrect repetition of a sentence. Further qualitative analysis classified the incorrect repeated sentences into error types in terms of Immigrant Turkish dialect features (ITfeat), error types that pattern monolingual Turkish DLD (DLDfeat), children or neither of both or unclear (UN). Null reactions were counted as errors, unless they were due to technical problems or errors by the investigators (missing data, less than 1% of the overall data).

3.3 Results

A total of 547 sentences from the SRT subtests was analysed (n TELD 3:T (SRT) = 349; n TÖDIL (SRT) = 198), with a correctness rate of 36% (TELD 3: T: 112/349 – 32%; TÖDIL: 40/198 – 20%). 87 sentences were errors of unclear origin. 152 (36%) incorrectly repeated sentences showed features that pattern errors known from monolingual Turkish speaking children with DLD.

The analysis here focuses on the remaining 156 incorrect sentences (TELD 3: T = 100/349 – 29%; TÖDIL: 56/198 – 28%). The children in our study repeated the sentences from the SRT using patterns typical for the Immigrant Turkish dialect.

These features are, for example, omission of possessive markers in genitive-possessive constructions, that appeared in 8% of all incorrect sentences (13/156 – 8%) (cf. example 8).

(8) | Omission of the possessive marker in genitive-possessive constructions | |||||

Standard Turkish (TÖDIL SRT item number 34): | ||||||

Dün | öfkeli bir | kaplanın | pençesinden | zor | kurtarıldık. | |

Yesterday | angry INDEF | tiger-GEN | paw-POSS-3SG-ABL difficult rescue-PASS-PAST-1PL | |||

‘Yesterday we hardly survived the paws of an angry tiger.’ Immigrant Turkish dialect: | ||||||

Dün | kaplanın | pençeden | zor | kurtarıldık. (041432; 12;0) | ||

Yesterday | tiger-GEN | paw-Ø-ABL | difficult | rescue-PASS-PAST-1PL | ||

More, substitutions of case markings (22/156 = 14%; DAT for ACC: 8; ACC for DAT: 2; LOC for ACC: 2; DAT for ABL: 3; ABL for DAT: 7)) or the omission of obligatory case markings (20/156= 13%; DAT: 6; ACC: 13), and, especially with genitive (20/156 = 13%), were observable (cf. example 9–11).

(9) | Substitution of dative with accusative; omission of dative | ||||

Standard Turkish (TEDIL SRT Item Number 27d) | |||||

Zeynep arkadaşlarına | ve | öğretmenine | hediye | verdi. | |

Zeynep | friend-PL-POSS-3SG-DAT | and | teacher-POSS-3SG-DAT present | give-PAST-3SG | |

‘Zeynep gave present to her friends and teacher.’ | |||||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | |||||

Zeynep | ve | arkadaşlarını | birşey | alıyordu. (024332; 9;2) | |

Zeynep | and friend-PL-POSS-3SG-ACC | something | buy-PROG-PAST-3SG | ||

Zeynep arkadasi | ve | ögretmenine | hediye | verdi. (BAY; 5;1) | |

Zeynep | friend-3SG-POSS-Ø and teacher-POSS-3SG-DAT | present | give-PAST-3SG | ||

(10) | Substitution of ablative with dative | ||||

Standard Turkish (TODIL SRT Item number 9) | |||||

Fabrikadan | çıkınca | çocuklar | arabayı | tamir ettiler. | |

Factory_ABL | come out-SUB | children | car-ACC | repair-PAST-3PL | |

‘When the children went out of factory, they repaired the car.” Immigrant Turkish dialect: | |||||

Fabrikaya (04432; 9;3) | çıkarken | çocuklar | arabayı | unuttu. | |

Fabrika-DAT | go-out-SUB | child-PL | car-ACC | forget-PAST-3SG | |

(11) | Omission of genitive case, omission of accusative case; substitution of dative with accusative | ||||

Standard Turkish (TÖDIL SRT Item Number 14) | |||||

Kadın | adamın | kendisini | sevdiğine | inanmadı | |

Woman | man-GEN | self-ACC | love-CV-POSS-3SG-DAT | believe-NEG-PAST-3SG | |

‘The woman did not believe that the man loves her”. | |||||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | |||||

Kadın | ama adamı | kendisi | sevdiğini | ||

Woman but | man-ACC-Ø | self-Ø | love-CV-POSS-3G-ACC | ||

inanmadı. | (040432; 9;3) | ||||

believe-NEG-PAST-3SG | |||||

Further, lexical dialect levelling (10/156 = 6%) was found, as well as blending of omission and substitution in the same sentences (cf. example 11). Note, however, that the avoidance of complexity by using finite clauses (40/156 = 26%) was most prominent among all errors (cf. example 12), and that several errors would appear in the same repeated sentence.

(12) | Finite clause instead of adverbial subordination | ||||

Standard Turkish (TÖDIL SRT Item number 9): | |||||

Fabrikadan | çıkınca | çocuklar | arabayı | tamir ettiler. | |

Factory_ABL | come out-SUB | children | car-ACC | repair-PAST-3PL | |

‘When the children went out of factory, they repaired the car.’ | |||||

Immigrant Turkish dialect: | |||||

Fabrikadan . | çıkmışlar | Çocuklar | arabayı tamir etmişler. (019332; 11;3) | ||

Factory-ABL | go out-EVD-3PL | child-PL | car-ACC repair-PAST-EVD-3PL | ||

Fabrikadan | çıktı. | Çocuklar | arabayı tamir ettiler. (036432; 11;2) | ||

Factory-ABL | go-out-PAST-3SG | child-PL | car-ACC repair- PAST-3PL | ||

Importantly, these sentences are correct by Immigrant Turkish dialect standards. Turkish- German bilingual children make use of the dialectal variety in the sentence repetition task, processing and understanding the sentences in the standard variety of Turkish correctly, and repeating them in their spoken Immigrant Turkish dialect.

4 Discussion: The Immigrant Turkish Dialect as a Heritage Variety and Its Implications for Language Assessment and Education

Immigrant Turkish as heritage language for bilingual children in Germany reflects the necessity of an acknowledgement of dialect input for language assessment. From a sociolinguistic point of view, it is remarkable, how differences between the Immigrant Turkish and standard Turkish have long been unattended as a factor most relevant for the validity of assessment tools in bilingual contexts. This might be due, however, to a lack of systematic investigations with broader populations of bilingual children with and without DLD in several countries.

The studies carried out within the IS0804 and the bi-sli networks, however, allow for new insights to the relevance of dialects for language input and assessment, since they provide research with a broad database and a fair number of participants for linguistic study. Further, earlier studies struggled with the (im)possibility of disentangling bilingual children with DLD from typically developing children (i.e. Paradis, 2008; Armon-Lotem et al., 2015; Tuller et al., 2018), so that reliable data for the evaluation of assessment tools in bilingual and bilectal populations is only emerging (i.e. Marinis et al., 2017; Theodorou et al., 2016; Abed Ibrahim & Fekete, 2019; Leivada et al., 2019; Chilla et al., in press).

Our results confirm former studies, underlying systematic differences between the standard variety or dialects in the country of origin, and the Immigrant Turkish dialect. The omission and/or substitution of case markings (i.e. Cindark & Aslan, 2004), as well as changes in genitive-possessive constructions (Dirim & Auer, 2004), and, most relevant, the use of finite and/or co-ordinated sentences instead of more complex structures continue to be prominent features of Immigrant Turkish dialect. If compared to monolingual speakers of the standard variety of Turkish, bilingual speakers of IT avoid complexity. Non-finite sentences are more prominent among bilingual IT speakers than finite clause coordination, and juxtaposition is more common than complex embedding (Treffers-Daller et al., 2006; Bayram, 2013; Herkenrath, 2014; Schroeder, 2016). However, some features, such as an overuse of ablative forms in locative contexts, or an omission of interrogative particles in yes-no questions, are characteristics of dialect levelling or, as for genitive-possessive without possessive marker, common in informal spoken Turkish and some dialects (i.e. Csató & Johanson, 1998).

The robustness of the Immigrant Turkish dialect as a heritage language for bilingual Turkish- German children is evident. Even if language proficiency was measured by an easy-to- administer and age- and language-appropriate task, IT children tend to repeat the sentences in the dialectal variety. However, sentence repetition tasks should be robust of language change phenomena, if the (in)correctness of answers was based on working memory capacities, only. The sentence repetitions of the IT dialect-speaking children here, though, refer to structural changes and to systematic deviations from the standard variety, and to the necessity and meaningfulness of grammatically motivated SRTs (i.e. Hamann & Abed Ibrahim, 2017). Since the data provided here contains of a homogeneous group of Turkish-German bilingual children without DLD, who took part in a comprehensive assessment procedure (i.e. Abed Ibrahim & Hamann, 2019) the high error rate in a SRT should not result from language disorder, children being under age or on limited cognitive development. The corpus is furthermore representative for the Turkish-German population of heritage children in Germany, since participants from different German Federal Countries (i.e. Baden-Württemberg, Berlin, Hamburg, Hessen) and from different living environments (cities/rural areas) attended. It is also true that the majority of test items (64%) was processed and repeated in the standard Turkish model, as expected.

If the scoring procedure considered IT sentences as correct, the overall correctness rate would increase considerably. Note, however, that the data also provide further evidence for an overlap between Immigrant Turkish and DLD features in bilinguals (i.e. Babur et al., 2007; Rothweiler et al., 2013; Topbaş et al., 2016; Chilla & Şan, 2017), since there are nearly the same number of sentences in the corpus (101 in the TEDIL and 51 in the TÖDIL), which are likewise characteristic for DLD in Turkish monolinguals. These features are, for example, the substitution of case markings (i.e. accusative for dative), or the omission of obligatory elements or suffixes. It is also true that the reduction of syntactic complexity is a distinctive feature of DLD in Turkish.

Thus, to avoid misdiagnosis, scoring of language proficiency in the bilectal context of Immigrant Turkish should not just rely on a transformation of raw scores based on knowledge of the dialectal input of the child, in the sense of adding a “bilectal error bonus”, as it has been proposed for bilinguals. Rather, further systematic study on the qualitative and quantitative differences between the language performances of IT speaking children with and without DLD with sensitive error type analysis could lead to a better understanding of clear patterns of DLD vs IT, respectively. Prospective test design should contain interpretation variability with respect to dialectal and/or DLD outcomes, and scoring (cf. Leivada et al., 2019). First steps have already been explored by, for example, Hamann and Abed-Ibrahim (2017); Theodorou et al. (2017); Abed-Ibrahim and Fekete (2019); Chilla et al. (in press).

Further studies might moreover investigate the specific heritage language situation of the IT dialect: Most IT-speaking children have no access to formal Turkish or literacy education. Education and assessment should further withdraw from the construction of homogeneous groups of “first language” children and adults in diglossia, bilingual and heritage language populations, implying sufficient language testing with assessment tools for monolingual contexts.

Sensitive qualitative research with respect to language attrition vs. IT vs. DLD features at different ages with broader cross-sectional studies would contribute to a dialectal-fair development of testing materials for bilectals, and especially for a population as large as this of Immigrant Turkish as dialect speakers in Germany.

References

Abed, I. L., & Fekete, I. (2019). What machine learning can tell us about the role of language dominance in the diagnostic accuracy of German LITMUS non-word and sentence repetition tasks. Frontiers Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02757

Acarlar, F., & Johnston, J. R. (2011). Acquisition of Turkish grammatical morphology by children with developmental disorders. Journal for Communication Disorders, 46(5), 728–738.

Acarlar, F., Miller J. F., & Johnston, J. R. (2006). Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) Turkish (Version 9) (Computer Software), Language Analysis Lab, University of Wisconsin –Madison. (Distributed by the Turkish Psychological Association).

Akıncı, M. A. (2008). Language use and biliteracy practices of Turkish-speaking children and adolescents in France. In V. Lytra & J. N. Joergensen (Eds.), Multilingualism and identities across contexts: Cross-disciplinary perspectives on Turkish- Speaking youth in Europe (pp. 85–108). University of Copenhagen Press.

Akıncı, M. A., Pfaff, C. W., & Dollnick, M. (2013). Orthographic and morphological aspects of written Turkish in France, Germany and Turkey. In I. Ergenc (Ed.), Proceedings of the Turkish linguistic conference, Antalya 2008 (pp. 363–372). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

Akoğlu, G., & Yağmur, K. (2016). First-language skills of bilingual Turkish immigrant children growing up in a Dutch submersion context. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 19(6), 706–721.

Aksu-Koç, A. (1994). Development of linguistic forms: Turkish. In R. Berman & D. I. Slobin (Eds.) Relating events in narrative: A crosslinguistic developmental study (pp. 329–388). Erlbaum.

Aksu-Koç, A., & Slobin, D. I. (1985). The acquisition of Turkish. In D. I. Slobin (Ed.), The crosslinguistic study of language acquisition. Volume 1: The data (pp. 839–878). Erlbaum.

Archibald, L. M., & Gathercole, S. E. (2006). Nonword repetition: A comparison of tests. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 970–983. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388

Armon-Lotem, S. (2014). Between L2 and SLI: inflections and prepositions in the Hebrew of bilingual children with TLD and monolingual children with SLI. Journal of Child Language, 41, 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000912000487

Armon-Lotem, S., de Jong, J., & Meir, N. (Eds.). (2015). Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment. Multilingual Matters.

Au, T. L., Knightly, L. M., Jun, S. A., & Oh, J. (2002). Overhearing: A language during childhood. Psychological Science, 13(3), 238–243.

Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung. (2016). Bildung in Deutschland 2016: ein indikatorengestützter Bericht mit einer Analyse zu Bildung und Migration. W. Bertelsmann Verlag.

Autorengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung. (2018). Bildung in Deutschland 2018. Bielefeld.

Aytemiz, A. (1990). Zur Sprachkompetenz türkischer Schüler in Türkisch und Deutsch: Sprachliche Abweichungen und soziale Einflussgrössen. Peter Lang.

Babur, E., Rothweiler, M., & Kroffke, S. (2007). Spezifische Sprachentwicklungsstörung in der Erstsprache Türkisch. Linguistische Berichte, 212, 377–402.

Backus, A. (2004). Turkish as an immigrant language in Europe. In T. K. Bhatia & W. C. Ritschie (Eds.), The handbook of bilingualism (pp. 689–724). Blackwell.

Backus, A. (2010). The role of codeswitching, loan translation and interference in the emergence of an immigrant variety of Turkish. Working Papers in Corpus-based Linguistics and Language Education, 5, 225–241.

Backus, A., & Boeschoten, H. (1998). Language change in immigrant Turkish. In G. Extra & J. Maartens (Eds.), Multilingualism in a multicultural context: Case studies on South Africa and Western Europe (pp. 221–237). Tilburg University Press.

Backus, A., Jørgensen, J. N., & Pfaff, C. W. (2010). Linguistic effects of immigration: Language choice, codeswitching and change in Western European Turkish. Language & Linguistics Compass, 4(7), 481–495.

Banaz, H. (2002). Bilingualismus und Code-switching bei der zweiten türkischen Generation in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Sprachverhalten und Identitätsentwicklung. Linguistik-Server Essen, www.linse.uniessen.de.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2019.

Baumgarten, N., Herkenrath, A., Schmidt, T., Wörner, K., & Zeevaert, L. (2007). Studying connectivity with the help of computer-readable corpora: Some exemplary analyses from modern and historical, written and spoken corpora. In J. Rehbein, C. Hohenstein, & L. Pietsch (Eds.), Connectivity in grammar and discourse (pp. 259–289). Benjamins.

Bayram, F. (2013). Acquisition of Turkish by heritage speakers: A processability approach. Dissertation, Newcastle University. https://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/1905. Accessed 15 Apr 2017.

Benmamoun, E., Montrul, S., & Polinsky, M. (2013). Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics; 39, 129–181.

Berliner Institut für empirische Integrations- und Migrationsforschung (BIM)/Forschungsbereich beim Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR Forschungsbereich). (2017).Vielfalt im Klassenzimmer. Wie Lehrkräfte gute Leistung fördern können. https://www.svr-migration.de/publikationen/vielfalt-im-klassenzimmer. Accessed 24 Nov 2019.

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., & Greenhalgh, T. (2016). CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study. Identifying language impairments in children. PLOS One, 11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158753

Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., & Greenhalgh, T. (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 58, 1068–1080.

Boeschoeten, H. (1994). L2 influence on L1 development: The case of Turkish children in Germany. In G. Extra & L. Verhoeven (Eds.), The cross-linguistic study of bilingual development (pp. 253–264). North- Holland.

Boeschoten, H. (2000). Convergence and divergence in migrant Turkish. In K. Mattheier (Ed.), Dialect and migration in a changing Europe (pp. 145–154). Lang.

Boeschoten, H., & Broeder, P. (1999). Zum Interferenzbegriff in seiner Anwendung auf die Zweisprachigkeit türkischer Migranten. In L. Johanson & J. Rehbein (Eds.), Türkisch und Deutsch im Vergleich (pp. 1–22). Harrassowitz.

Caspar, U., & Leyendecker, B. (2011). Deutsch als Zweitsprache. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 43, 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637/a000046

Chilla, S., & Şan, N. H. (2017). Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Diagnostik erstsprachlicher Fähigkeiten: Türkisch-deutsche und türkisch-französische Kinder im Vergleich. In C. Yildiz et al. (Eds.), Sprachen 2016: Russisch und Türkisch im Fokus (pp. 175–205). Peter Lang.

Chilla, S., Rothweiler, M., & Babur, E. (2013). Kindliche Mehrsprachigkeit. Grundlagen – Störungen Diagnostik. Reinhardt.

Chilla S., Hamann C., Prévost P., Abed Ibrahim L., Ferré S., dos Santos C., et al. (in press). The influence of different first languages on L2 LITMUS-NWR and L2 LITMUS-SRT in French and German: A crosslinguistic approach. In K.K. Grohmann, & S. Armon-Lotem (Eds.), LITMUS in action: Comparative studies across Europe, TILAR. John Benjamins.

Cho, G., Shin, F., & Krashen, S. (2004). What do we know about heritage languages? What do we need to learn about them? Multicultural Education, 11(4), 24–26.

Cindark, İ., & Aslan, S. (2004). Deutschlandtürkisch? Open-Access Publikationsserver des IDS. http://www.ids-mannheim.de/prag/soziostilistik/Deutschlandtuerkisch.pdf. Accessed 15 Nov 2019.

Conti-Ramsden, G., Botting, N., & Faragher, B. (2001). Psycholinguistic markers for specific language impairment (SLI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42, 741–748.

Cook, V. (2003). The effects of the second language on the first. Multilingual Matters.

Csató, É. Á., & Johanson, L. (Eds.). (1998). The Turkic languages. Routledge.

Cummins, J. (2005). A proposal for action: Strategies for recognizing heritage language competence as a learning resource within the mainstream classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 89(4), 585–592.

de Almeida, L., Ferrré, S., Morin, E., Prévost, P., dos Santos, C., Tuller, L., et al. (2017). Identification of bilingual children with specific language impairment in France. Linguistic Approaches Bilingualism, 7, 331–358. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.15019.alm

De Jong, J., Cavuş, N., & Baker, A. (2010). Language impairment in Turkish-Dutch Bilingual children. In S. Topbaş & M. Yavaş (Eds.), Communication disorders in Turkish in monolingual and multilingual settings (pp. 288–300). Multilingual Matters.

Dirim, İ. (2009). Zuhause sprechen wir deutsch und aramäisch. Befunde zu Migration und Sprache. Schüler, 2009, 58–59.

Dirim, I., & Auer, P. (2004). Türkisch sprechen nicht nur die Türken: Über die Unschärfebeziehung zwischen Sprache und Ethnie in Deutschland (Linguistik – Impulse & Tendenzen). Walter de Gruyter.

Doğruöz, A. S., & Backus, A. (2007). Postverbal elements in Immigrant Turkish: Evidence of change? International Journal of Bilingualism, 11(2), 185–220.

Doğruöz, S., & Backus, A. (2009). Innovative constructions in Dutch Turkish: An assessment of on- going contact-induced change. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition, 12(1), 41–63.

Dollnick, M. (2013). Konnektoren in türkischen und deutschen Texten bilingualer Schüler: eine vergleichende Langzeituntersuchung zur Entwicklung schriftsprachlicher Kompetenzen. Dissertation. Peter Lang Verlag.

Engel de Abreu, P. M. J., Puglisi, L. M., Cruz-Santos, A., & Befi-Lopes, D. M. (2013). Executive functions and Specific Language Impairment (SLI): A cross-cultural study with bi- and monolingual children from low income families in Luxembourg, Portugal and Brazil. In Paper presented at the 13th International Congress for the Study of Child Language, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Ertanir, B., Kratzmann, J., Frank, M., Jahreiss, S., & Sachse, S. (2018). Dual language competencies of Turkish–German children growing up in Germany: Factors supportive of functioning dual language development. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02261

Extra, G., & Yağmur, K. (Eds.). (2004). Urban multilingualism in Europe immigrant minority languages at home and school. Multilingual Matters.

Feltes, T., Marquardt, U., & Schwarz, S. (2013). Policing in Germany: Developments in the last 20 years. In G. Meško, C. B. Fields, B. Lobnikar, & A. Sotlar (Eds.), Handbook on policing in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 93–113). Springer.

Fishman, J. A. (2001). 300-plus years of heritage language education in the United States. In J.K. Peyton, D. A. Ranard, & S. McGinnis (Eds.), Heritage languages in America: Preserving a national resource (pp. 87-97). : Center for Applied Linguistics.

Fleckstein, A., Prévost, P., Tuller, L., Sizaret, E., & Zebib, R. (2018). How to identify SLI in bilingual children: A study on sentence repetition in French. Language Acquisition, 25(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2016.1192635.

Földes, C. (2005). Kontaktdeutsch. Zur Theorie eines Varietätentyps unter transkulturellen Bedingungen von Mehrsprachigkeit. Narr.

Gagarina, N. (2014). Diagnostik von Erstsprachkompetenzen im Migrationskontext. In S. Chilla & S. Haberzettel (Eds.), Handbuch Sprachentwicklung und Sprachentwicklungsstörungen 4: Mehrsprachigkeit (pp. 19–37). Elsevier.

Gagarina, N., Klop, D., Kunnari, S., Tantele, K., Välimaa, T., Balčiūnienė, I., Bohnacker, U., & Walters, J. (2012). MAIN – Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives. ZAS Papers in Linguistics, 56. ZAS.

Gogolin, I. (1994). Der monolinguale Habitus der multilingualen Schule. Waxmann.

Hamann, C., & Abed Ibrahim, L. (2017). Methods for identifying specific language impairment in Bilingual populations in Germany. Frontiers in Communication, 2(19). https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2017.00016

Hamann, C., Chilla, S., Ruigendijk, E., & Abed Ibrahim, L. (2013). A German sentence repetition task: testing bilingual Russian/German children. In Poster session presented at the COST Meeting in Kraków, Kraków, Poland.

Hammill, D. D., & Newcomer, P. L. (2008). Test of language development-primary. 4th ProEd Inc.

Herkenrath, A. (2007). Discourse coordination in Turkish monolingual and Turkish–German bilingual children’s talk: Işte. In J. Rehbein, C. Hohenstein, & L. Pietsch (Eds.), Connectivity in grammar and discourse (pp. 291–328). Benjamins (Hamburg Studies on Multilingualism 5).

Herkenrath, A. (2014). The acquisition of –DIK and its communicative range in monolingual versus bilingual constellations. In N. Demir, B. Karakoç, & A. Menz (Eds.), Turcology and linguistics (pp. 219–236). Hacettepe University Press.

Herkenrath, A., Karakoç, B., & Rehbein, J. (2003). Interrogative elements as subordinators in Turkish: Aspects of Turkish–German bilingual children’s language use. In N. Müller (Ed.), (in)vulnerable domains in multilingualism (pp. 221–270). Benjamins (Hamburg Studies in Multilingualism 1).

Hess-Gabriel, B. (1979). Zur Didaktik des Deutschunterrichts für Kinder türkischer Muttersprache. Eine kontrastivlinguistische Studie. Narr.

Hresko, W. P., Hammill, D. D., & Reid, D. K. (1991). Test of early language development: TELD-2. Pro-ed.

Johanson, L. (1991). Zur Sprachentwicklung der ‘Turcia Germanica’. In I. Baldauf, K. Kreiser, & S. Tezcan (Eds.), Türkische Sprachen und Literaturen (pp. 199–212). Harrassowitz.

Johanson, L. (1993). Code-copying in immigrant Turkish. In G. Extra & L. Verhoeven (Eds.), Immigrant languages in Europe (pp. 197–221). Multilingual Matters.

Johanson, L. (2002). Contact-induced linguistic change in a code-copying framework. In M. C. Jones & E. Esch (Eds.), Language change: The interplay of internal, external and extra-linguistic factors (Contributions to the Sociology of Language, 86) (pp. 285–313). Mouton de Gruyter.

Johnson, C. J., Beitchman, J. H., Young, A., Escobar, M., Atkinson, L., Wilson, B., & Wang, M. (1999). Fourteen-year follow-up of children with and without speech/language impairments: Speech/language stability and outcomes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42(3), 744–760.

Kambanaros, M., Grohmann, K. K., & Michaelides, M. (2013). Lexical retrieval for nouns and verbs in typically developing bilectal children. First Language, 33(2), 182–199.

Karakoç, B. (2007). Ein Überblick über postverbiale Konverbien im Nogaischen. In H. Boeschoten, & H., Stein (Eds.), Einheit und Vielfalt in der türkischen Welt Turcologica 69 (pp. 215-229). : Harrassowitz.

Kazak-Berument, S., & Güven, S. (2010). Türkçe Alıcı ve İfade Edici Dil Testi (TİFALDİ). Türk Psikologlar Derneği.

Klem, M., Melby-Lervåg, M., Hagtvet, B., Halaas Lyster, S. A., Gustafsson, J. E., & Hulme, C. (2015). Sentence repetition is a measure of children’s language skills rather than working memory limitations. Developmental Science, 18, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12202

Koneva, E. V., & Gural, S. K. (2015). The role of dialects in the German Society. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 200, 248–252.

Küppers, A., Şimsek, Y., & Schroeder, C. (2015). Turkish as a minority language in Germany: Aspects of language development and language instruction. Zeitschrift für Fremdsprachenforschung, 26(1), 29–51.

Lancaster, H. S., & Camarata, S. (2019). Reconceptualizing developmental language disorder as a spectrum disorder: Issues and evidence. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 54(1), 79–94.

Leivada, E., D’Allessandro, & Grohmann, K. K. (2019). Eliciting big data from small, young, or non- standard languages: 10 experimental challenges. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 313. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.1019.00313

Leonard, L. B. (2010). Language combinations, subtypes, and severity in the study of bilingual children with specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31, 310–315.

Marinis, T., & Armon-Lotem, S. (2015). Sentence repetition. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (pp. 95–124). Bristol, Multilingual Matters.

Marinis, T., Armon-Lotem, S., & Pontikas, G. (2017). Language impairment in bilingual children state of the art 2017. In J. Rothman & S. Unsworth (Eds.), Linguistic approaches to bilingualism (Vol. 7, pp. 265–276). John Benjamins.

Meir, N., Walters, J., & Armon-Lotem, S. (2016). Disentangling SLI and bilingualism using in sentence repetition tasks: the impact of L1 and L2 properties. International Journal of Bilingualism, 20, 421–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006915609240

Menz, A. (1991). Studien zum Türkisch der zweiten deutschlandtürkischen Generation. M.A. Thesis. Mainz University.

Montrul, S. (2009). Incomplete acquisition of tense-aspect and mood in Spanish heritage speakers. The International Journal of Bilingualism, 13(3), 239–269.

Montrul, S., Foote, R., & Perpiñan, S. (2008). Gender agreement in adult second language learners and Spanish heritage speakers: The effects of age and context of acquisition. Language Learning, 58(3), 3–54.

Montrul, S.A., Bhatt, R., & Bennamoun, A. (2010). Morphological errors in Hindi, Spanish and Arabic heritage speakers. In Paper presented at the Invited Colloquium on the Linguistic Competence of Heritage Speakers Second Language Research Forum, University of Maryland, USA.

Norbury, C. F., Gooch, D., Wray, C., Baird, G., Charman, T., Simonoff, E., Vamvakas, A., & Pickles, A. (2016). The impact of nonverbal ability on prevalence and clinical presentation of language disorder: Evidence from a population study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(11), 1247–1257.

Onar-Valk, P. (2015). Transformation in Dutch Turkish Subordination? Converging evidence of change regarding finiteness. Dissertation, University of Tilburg. LOT.

Paradis, J. (2008). Early bilingual and multilingual acquisition. In P. Auer & L. Wei (Eds.), Handbook of multilingualism and multilingual communication (pp. 15–44). De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110198553.1.15

Paradis, J. (2010). The interface between bilingual development and specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31, 3–28.

Paradis, J., Rice, M., Crago, M., & Marquis, J. (2008). The acquisition of tense in English: distinguishing child L2 from L1 and SLI. Applied Psycholinguistics, 29, 1–34.

Pfaff, C. W. (1991). Turkish in contact with German: Language maintenance and loss among immigrant children in West Berlin. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 90, 97–129.

Pfaff, C. W. (1994). Early bilingual development of Turkish children in Berlin. In G. Extra & L. Verhoeven (Eds.), The Cross- linguistic study of bilingual development (pp. 75–97). Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen.

Polinsky, M. (2018). Heritage languages and their speakers. Cambridge University Press.

Polinsky, M., & Kagan, O. (2007). Heritage languages: In the ‘wild’ and in the classroom. Language and Linguistics Compass, 1(5), 368–395.

Polišenská, K., & Kalpaková, S. (2014). Improving Child compliance on a computer-administered nonword repetition task. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 57(3). https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2013/13-0014) .

Rash, F. (2002). Die deutsche Sprache in der Schweiz. Mehrsprachigkeit, Diglossie und Veränderung. Peter Lang.

Rehbein, J. (2001). Turkish in European societies. Lingua e Stile, 36, 317–334.

Rehbein, J., & Karakoç, B. (2004). On contact-induced language change of Turkish aspects: Languaging in bilingual discourse. In C. B. Dabelsteen & J. N. Jørgensen (Eds.), Languaging and language practices. Copenhagen studies in bilingualism (Vol. 36, pp. 125–149). University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Humanities.

Rehbein, J., Herkenrath, A., & Karakoç, B. (2009). Turkish in Germany – On contact-induced language change of an immigrant language in the multilingual landscape of Europe. Multilingualism and universal principles of linguistic change. Special issue of sprachtypologie und universalienforschung – Language typology and universals, 62, 171–204.

Riphahn, R., Sander, M., & Wunder, C. (2010). The welfare use of immigrant and natives in Germany. The case of Turkish immigrants. LASER Discussion papers- Paper No. 44.

Rothmann, J. (2009). Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingual: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13(2), 359–389.

Rothweiler, M., Chilla, S., & Babur, E. (2010). Specific language impairment in Turkish: Evidence from case morphology in Turkish–German successive bilinguals. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 24(7), 540–555.

Rothweiler, M., Chilla, S., & Babur, E. (2013). Specific Language Impairment in Turkish. Evidence from Turkish-German Successive Bilinguals. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 24(7), 540–555.

Rowe, C., & Grohmann, K. K. (2013). Discrete bilectalism: Towards co-overt prestige and diglossic shift in Cyprus. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 224, 119–142.

Sarı, M. (1995). Der Einfluß der Zweitsprache (Deutsch) auf die Sprachentwicklung türkischer Gastarbeiterkinder in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Lang.

Sarı, M. (2006). Intra-linguistic interference triggered by inter-linguistic interference. In H. Boeschoten & L. Johanson (Eds.), Turkic languages in contact (Turcologica 61, pp. 176–185). Harrassowitz.

Schellhardt, C., & Schroeder, C. (2013). Nominalphrasen in deutschen und türkischen Texten mehrsprachiger Schüler/innen. In K. M. Köpcke & A. Ziegler (Eds.), Deutsche Grammatik im Kontakt in Schule und Unterricht (pp. 241–262). de Gruyter.

Schellhardt, C., & Schroeder, C. (eds.). (2015). MULTILIT. Manual, criteria of transcription and analysis for German, Turkish and English. Universitätsverlag. https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4ubp/frontdoor/index/index/docId/8039. Accessed 15 Sept 2019.

Schellhardt, C., & Schroeder, C. (2015). Nominalphrasen in deutschen und türkischen Texten mehrsprachiger Schüler/innen. In K.-M. Köpcke & A. Ziegler (Eds.), Deutsche Grammatik im Kontakt in Schule und Unterricht (pp. 241–261). de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110367171-011

Schroeder, C. (2007). Orthography in German-Turkish language contact. In F. Baider (Ed.), Emprunts linguistiques, empreintes culturelles. Métissage orient-occident (Sémantiques, pp. 101–122). l’Harmattan.

Schroeder, C. (2009). gehen, laufen, torkeln: Eine typologisch gegründete Hypothese für den Schrift-spracherwerb in der Zweitsprache Deutsch mit Erstsprache Türkisch. In K. Schramm & C. Schroeder (Eds.), Empirische Zugänge zu Spracherwerb und Sprachförderung in Deutsch als Zweitsprache. Waxmann. 9783830972204.

Schroeder, C. (2014). Türkische Texte deutsch-türkisch bilingualer Schülerinnen und Schüler in Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik, 44, 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03379515

Schroeder, C. (2016). Clause combining in Turkish as a minority language in Germany. In M. Güven, D. Akar, B. Öztürk, & M. Kelepir (Eds.), Exploring the Turkish Linguistic landscape: Essays in honour of Eser E. Erguvanlı-Taylan (pp. 81–102). John Benjamins.

Schroeder, C., & Dollnick, M. (2013). Mehrsprachige Gymnasiasten mit türkischem Hintergrund Schreiben auf Türkisch. http://biecoll.ub.unibielefeld.de/volltexte/2013/5274/ index_de.htm.pdf. Accessed 3 Mar 2017.

Schroeder, C., & Stölting, W. (2005). Mehrsprachig orientierte Sprachstandfeststellungen für Kinder mit Migrationshintergrund. In I. Gogolin, U. Neumann, & H. J. Roth (Eds.), Sprachdiagnostik bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund (pp. 59–74). Waxmann.

Şimşek, Y. & Schroeder, C. (2011). Migration und Sprache in Deutschland am Beispiel der Migranten aus der Türkei und ihrer Kinder und Kindeskinder.In Ş, Ozil, M. Hofmann, & Y. Dayıoğlu- Yücel (Eds.), Fünfzig Jahre türkische Arbeitsmigration in Deutschland (pp. 205–228). V&R unipress.

Stothard, S., Snowling, M., Bishop, D., Chipchase, C., & Kaplan, C. (1998). Language-impaired preschoolers: A follow-up into adolescence. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41, 407–418.

Theodorou, E., Kambanaros, M., & Grohmann, K. K. (2016). Diagnosing bilectal children with SLI: Determination of identification accuracy. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 30(12), 925–943.

Theodorou, E., Kambanaros, M., & Grohmann, K. K. (2017). Sentence repetition as a tool for screening morphosyntactic abilities of bilectal children with SLI. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02104

Thordardottir, E. (2015). Proposed diagnostic procedures for use in bilingual andcross-linguistic contexts. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (pp. 331–358). Multilingual Matters.

Tomblin, J. B. (2010). The EpiSLI database: A publicly available database on speech and language. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41(1), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1044/0161-1461(2009/08-0057).

Tomblin, T., Peng, S. C., Spencer, L. J., & Lu, N. (2008). Long-term trajectories of the development of speech sound production in Pediatric Cochlear implant recipients. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(5), 1353–1368. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388

Topbaş, S. (1997). Turkish children’s phonological acquisition: Implications for phonological disorders. European Journal of Disorders of Communication, 32, 377–397.

Topbaş, S. (1999). Dil ve konuşma sorunlu çocukların sesbilgisel çözümleme yöntemi ile değerlendirilmesi ve konuşma dillerindeki sesbilgisel özelliklerin betimlenmesi. Dissertation. Anadolu University, Eskişehir.

Topbaş, S. (2005). 2. Dil ve Konuşma Bozuklukları Kongresi Bildiriler Kitabı. KOK.

Topbaş, S. (2007). Turkish Speech acquisition. In S. McLeod (Ed.), The international guide to speech acquisition (pp. 566–579). Thomson Delmar Learning.

Topbaş, S., & Güven, S. (2008). Reliability and validity results of the adaptation of TELD-3 for Turkish speaking children: Implications for language impairments. In Oral presentation at 12th Congress of the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association, İstanbul, Turkey.

Topbaş, S., & Güven, S. (2011). Türkçe Erken Dil Gelişim Testi-TEDİL-3. Detay.

Topbaş, S., Güven, S., Uysal, A. A., & Kazanoğlu, D. (2016). Language impairment in Turkish-speaking children. In B. Haznedar & F. N. Ketrez (Eds.), The acquisition of Turkish in childhood (pp. 295–323). Benjamins.

Topbaş, S., & Güven, S. (2017). Türkçe Okul Çağı Dil Gelişimi Testi TODİL. Detay.

Topbaş, S., & Yavaş, M. (Eds.). (2010). Communication disorders in Turkish in monolingual and multilingual settings. Multilingual Matters.

Treffers, D., Jeanine, A., Özsoy, S., & Van Hout, R. (2006). (In)complete Acquisition of Turkish among Turkish-German Bilinguals in Germany and Turkey: An analysis of complex embeddings in narratives. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(3), 248–276.

Tuller, L. (2015). Clinical use of parental questionnaires in multilingual contexts. In S. Armon-Lotem, J. de Jong, & N. Meir (Eds.), Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment (pp. 229–328). Multilingual Matters.

Uzuntaş, A. (2008). Muttersprachliche Sprachstandserhebung bei zweisprachigen türkischen Kindern im deutschen Kindergarten. In B. Ahrenholz (Ed.), Zweitspracherwerb: Diagnosen, Verlaeufe, Voraussetzungen (pp. 65–91). Fillibach Verlag.

Valdés, G. (2000). Introduction. In Spanish for native speakers (Vol. I. AATSP Professional Development Series Handbook for Teachers K-16). Hartcourt College.

Vinther, T. (2002). Elicited imitation: a brief overview. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 42, 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1473-4192.00024

Yagmur, K., & Akinci, M. A. (2003). Language use, choice, maintenance, and ethnolinguistic vitality of Turkish speakers in France: Intergenerational differences. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 164, 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2003.050

Acknowledgements and Funding

We are grateful to Christoph Schroeder, University of Potsdam, for the permission to analyse the MULTILIT data corpus. MULTILIT is a binational project and financed by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and its French counterpart ANR (https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4-ubp/frontdoor/index/index/docId/8039). The project deals with language abilities of multilingual children and adolescents with migrant background in France and Germany, in particular, those with Turkish (and Kurdish) as home language(s). Thiy study is part of the BiLaD project (Bilingual Language Development: Typically Developing Children and Children with Specific Language Impairment; financed by a joint grant (German DFG: HA 2335/6-1, CH 1112/2-1, and RO 923/3-1 and French ANR grant ANR-12-FRAL-0014-01) and the BiliSAT project (Bilingual Language Development in School-age Children with/without Language Impairment with Arabic and Turkish as First Languages; financed by the DFG 2017-2019; CH1112/4-1, and HA 2335/7-1). The author thanks all project participants and collaborators, especially Cornelia Hamann, Lina Abed Ibrahim, and Hilal Şan. I am appreciative to Kleanthes K. Grohmann and Elinor Saiegh-Haddad for their enriching comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chilla, S. (2022). Assessment of Developmental Language Disorders in Bilinguals: Immigrant Turkish as a Bilectal Challenge in Germany. In: Saiegh-Haddad, E., Laks, L., McBride, C. (eds) Handbook of Literacy in Diglossia and in Dialectal Contexts. Literacy Studies, vol 22. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80072-7_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80072-7_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-80071-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-80072-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)