Abstract

After several decades of rather sporadic use in the scientific literature, the concept of hidden geographies is still usually based on provisional definitions that support the specific geographical hiddenness of the topic presented in a publication. This chapter focuses on hidden geographies, with the aim of providing a usable, not necessarily definitive understanding and definition of the concept. After a conceptual-semantic view at hidden geographies, the meanings of the concept and the term are presented, based on the analysis of literature, which provides a colourful variety of connotations and names of the concept in practise. In the discussion, some of the contexts underlying the concept under study are highlighted, as well as questions regarding its understanding and use, such as understanding the blurred line between hidden and revealed geography, and the roles of geography and geoinformatics in revealing or hiding geographies. Finally, a general definition and some specific definitions are proposed, linked to four layers of understanding of the concept: undiscovered, uncognised, unpublished and deliberately hidden geographies.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

We could hardly find stronger foundations to illustrate the importance of geography than Aristotle’s assertion that place gives order to the world (Bonnet 2014: xii) and Immanuel Kant’s understanding that it (geography) is one of the two basic forms of human knowledge (Bonnett 2008: 2). Although the statements may be outdated, simplistic and, in the latter case, also biased (Kant introduced the study of geography at the University of Königsberg, in 1756, and lectured on this subject for forty years; May 1970), they leave little doubt: when geographical information is missing, or hidden, human knowledge, abilities and activities are considerably curtailed.

From a very broad perspective of our collective (civilisational) knowledge, we may like to think that humans have become quite familiar with the Earth, given that its entire surface has been surveyed, remotely sensed and mapped. Yet a steady and increasing stream of new (geographical) information and knowledge reminds us of the extent of what remains unknown about our planet and its changing nature.

The successful functioning of people and societies requires a successful perception and cognition of the circumstances in the physical and social environment in which we live. To be successful in everyday life, though, as individuals, we need not know everything. As Tuan (1977: 85) put it, the geographical “knowledge we have as individuals and as members of a particular society remains very limited, selective, and biased”. Despite imperfect geographical information and knowledge and limited abilities to think geographically we—as individuals and societies—have to cope with everyday or long-term challenges. To do so, we need both geographical knowledge and the abilities to act effectively in new situations. This knowledge is accumulated and strengthened through formal and informal education as well as through personal or collectively shared experiences. This justifies the importance of learning just-in-case about previously unknown geographies, like through geography lessons in schools, reading literature or following the media news.

In a new, unknown situation, the knowledge we have may be insufficient to act effectively by following a learned routine. In new situations, learning may also involve getting to know and evaluating previously unknown geographies, if we need to consider them, and if circumstances allow. Such situational and selective learning usually only takes place when the environment is so unfamiliar or extraordinary that we consciously update our existing mental maps of our living environment (Holloway and Hubbard 2001: 48). This way of learning and acting in new situations requires special knowledge and abilities, the results of our lifelong learning and training, e.g. geographic awareness, spatial contextual awareness (Freksa et al. 2007) and spatial abilities (Tuan 1977).

From a personal point of view, many geographies, even those at the local level, are unknown to us—to our senses and cognition. Consequently, we as individuals live on a planet where unknown geographies prevail. Such geographies are, therefore, not an occasional or minor information-related problem. But living with them is not necessarily a problem, and our everyday encounters with them need not be very dramatic. We function despite them. Sometimes we try to reveal them, while at the same time we also contribute to them throughout our lives.

In this chapter, we focus on unknown geographies, which we call hidden geographies. Our aim is to contribute to their conceptualisation, to the awareness of the relevance of the concept and to the debate on its possible meanings, uses and implications. The concept is only sporadically used in literature and other media. It may seem neglected from a scientific point of view, and by textbooks, perhaps because it seems such a straightforward subject. Pointing out the missing geographical information, which is related to our limited knowledge and the weaknesses of our spatial abilities, can be consciously or subconsciously avoided. However, hidden geographies can have many meanings that relate to a number of different types of hiddenness, ranging from the physically or visually unperceivable to a lack of geographic knowledge and abilities. Understanding hidden geographies, then, is not straightforward. We can see them as one of the very central reasons or motivations for geographical exploration and discovery, including scientific research in geography and related spatial disciplines. When we imagine the possible or known impacts such missing information and knowledge have on our understanding of the world, our spatial decisions and our behaviour, we believe that they deserve closer consideration.

In this chapter, we do the following:

-

take a conceptual-semantic look at hidden geographies;

-

present the meanings of the concept and the term hidden geographies on the basis of the analysis of literature;

-

provide a general definition and some specific definitions of hidden geographies;

-

comment on the roles of geography and geoinformatics in revealing and hiding geographies.

First, we focus on semantics, relating the concept of hidden geographies to various meanings of the words constituting it. As demonstrated in the following section, such elementary meanings cover quite a rich and extensive domain, and will probably—and successfully enough—serve as its basic understanding. After clarifying the idea behind hidden geographies, an overview of its use and naming in practise is given, based mainly on the examination of the scientific literature. A summary of the characteristics of the concept, extracted from the outcomes of the semantic and literature analyses, exposes selected aspects that we consider to be particularly important for our debate, such as a blurred line between geographies that are hidden and revealed, and the life cycle of hidden geography. Finally, a general definition of the concept of hidden geography and some definitions of its specific meanings are given, based on what we have learned about the concept so far. In the discussion that follows, the roles of geography and geoinformatics in revealing or hiding geographies, as well as in solving the increasing problem of informational overburdening, are discussed.

2 Concept and Term

As we are approaching such a loosely defined concept as hidden geographies, we distinguish between the concept as the idea, in terms of both a generalisation and a deeper meaning, and the term used as the name of the idea, in how it signifies the concept. It is the concept, its interpretation and definition, that is the focus of this chapter. The term is considered to be a rather practical matter.

Various terms with different connotations are used in the literature to address the concept. It seems quite unlikely that a common understanding of the concept will emerge naturally, without involving a theoretical debate. As “there is no such thing as intuitive understanding of ordinary language—at any rate if we are speaking about the more subtle kind of communication” (Hansen 2006: 6), we start with a basic semantic analysis of the words used in the phrase hidden geographies.

2.1 Geography

Geography as a discipline is defined in many ways, from Eratosthenes’s “writing the Earth” to a contemporary definition such as “the study of the ways in which space is involved in the operation and outcome of social and biophysical processes” (Gregory 2009: 288). In the search for a comprehensive understanding of what is geography as a discipline and what it does, Bonnett (2008) emphasises that it is about studying the world, “an attempt to find and impose order on a seemingly chaotic world” (ibid.: 6). As a holistic discipline, geography plays an important integrative role and resists the current intellectual specialisation/fragmentation processes. This conceptualisation, therefore, emphasises geography as a discipline, its complexity, its ways of studying and explaining the Earth, its holistic and integrative character and the spatiality of its focus.

Another denotation of the word geography brings an important perspective to our discussion: geography as a particular object of enquiry; “something has a geography like it has a history” (Gregory 2009: 287). As used in previous literature, the word geography, within the phrase, hidden geographies, usually refers to this version of the meaning of the concept. The most obvious or at least the most common analogy to the latter denotation of geography is a map. This analogy may work well for many geographers, looking at the world through the lens of spatial science, like Haggett (1995). When Haggett writes about his conception of geography, he uses characterisations that include “patterns of human occupation of the earth”, “science of distributions”, “emphasis on space and on geometry”. If maps are representations of spatial structures, then geography is “the art of the mappable” (Johnston and Sidaway 2016: 102). But such views are problematized by many geographers as oversimplifying and narrow—“to root geography in mapping is a suffocating fantasy” (Bonnett 2008: 91). Doubts have been expressed about how well a map can represent actual places or landscapes, and how well it can serve human perception, cognition of and behaviour in these places (e.g. Tuan 1977). The constraints on the design and use of maps relate to the representation and cognition of known, revealed geographies. These constraints may actually lead in the opposite direction to the goal of mapping, and as a result the geographies represented remain hidden, at least at the cognitive level.

In setting the scene for further debate, we retain a broad definition of geography, somewhat broader than suggested by the mapping analogy. As it relates to absolute and contextual locations/spatial distributions, the terms absolute and contextual geography are used. Absolute geography is defined by the position of a phenomenon, e.g. using GPS coordinates, position on a map, street address or similar. Usually, this position is static, in 2D space, but can also be dynamic and/or in 3D space. Absolute geography refers to individual places or distribution of several places. Contextual geographyFootnote 1 is defined by the position (or spatial distribution) of a phenomenon in relation to another phenomenon or phenomena. The relationship can be spatial, such as any combination of distance, direction, adjacency, vicinity, spatial inclusion/overlay, and the like, as in the example the fuel station is 400 meters north of the house. We may think of such cases in terms of relative location. But the contextual relationship can also be temporal and/or based on the characteristics of the phenomena or places involved, as in, for example, the fuel is more expensive at the fuel stations on the highways. The contextual information can also be entirely subjective, personal, based on memories or emotions, as in, for example, I have my beloved places all around the city. Many absolute and contextual geographies can potentially be mapped. Absolute geographies must be based on, or transformable to a coordinate system we are able to apply. Contextual geographies must be transformed into absolute geographies before mapping, or we can map them without absolute georeference, as in the case of a hand-drawn treasure map or a sketch map showing a picnic spot. In the latter cases, geography can be revealed to the reader if he knows the geographical context in order to make the necessary georeferencing required for the practical use of such a map.

There is another level of the detachment of a geography from a mapping analogy. As mentioned later in the literature overview, some places—such as those that are legendary, mystical, imaginary—exist, often only in imagination, beliefs, narratives, or propaganda, but from time to time also in reality. Sometimes such imagined geographies can even be mapped, but it seems more likely that their absolute location is not known. This is perhaps not even necessary for them to function on an imaginary, symbolic level. Such geographies occasionally become the focus of geographical research, and they are also an interesting topic in the context of hidden geographies.

2.2 Hidden Geographies

The word hidden has several synonyms and antonyms (Table 1). Let us take hidden and revealed as representative examples. Hidden may be a good candidate for the role of constituting a term representing the concept of hidden geographies because it has so many possible connotations, it has already been in use, but not often or consistently enough to settle down and narrow down its meaning.

Hidden geographies could refer to hidden disciplinary (geographical) reasoning, methods or activities. But, as already mentioned, they have so far more often referred to hidden locations and distributions of certain phenomena, objects or places. From the list of synonyms of hidden and the variety of meanings of geography, we can extract a very wide range of existing and also potential nuances of hidden geographies’ meanings. Some of them do not seem usable, at least not in a scientific text; a few others not included in this list are touched upon in the following sections.

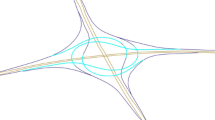

As a way of beginning to understand hidden geographies, we argue that it is important to consider whether what is hidden results from a deliberate act of hiding, or whether the hiddenness arises from an inability to perceive. This consideration serves as the basis for a model with 4 layers of hiddenness of geographies (Fig. 1), which is used in our further discussion.

Although expressed in terms of geography as a spatial aspect of phenomena, these layers can also be transformed to support the discussion of geography as a discipline, for example, as layers of hidden geographical disciplinary knowledge, models, interpretations.

Undiscovered geographies exist and, despite no one knowing about them,Footnote 2 they can have a minor or significant impact on other phenomena and processes in the landscape. Uncognised geographies include all hidden geographies that are discovered (by someone) but are not known, especially not at higher cognitive levels, to others, individually or collectively. Unpublished geographies are not accessible to cognition because geographic information about phenomena has not been made available to the public, either in visual (such as on a map), acoustic or other forms accessible to human senses and perception. Unpublished geographies are often also deliberately hidden. Such a schematic representation helps to organise the general understanding and discussion of the concept. However, it should be used flexibly enough to allow for some exceptions to the presented hierarchy of the layers, which are discussed later in this chapter.

3 Connotations of the Concept

Having examined the words in the phrase hidden geographies, we now look at how it occurs in literature. A systematic analysis of all the specific connotations is, of course, beyond the scope of this chapter. By reviewing examples of the occasional use and naming of the concept,Footnote 3 we hope to demonstrate its breadth and perhaps stimulate deeper analysis and theorising in the future.

The examples are grouped unevenly, according to the varying presence in the literature, and pragmatically, to support the presentation of the four layers of the concept (Fig. 1). The grouping is not intended to suggest particular types of hidden geographies. As these layers sometimes overlap, some of the examples could be used to represent more than one layer.

3.1 Undiscovered Geographies

It seems quite reasonable to expect little scientific literature on geographies of material or non-material phenomena that exist, but have not yet been discovered. However, this is only partly true. Apart from the (not necessarily scientific) search for legendary places, even hidden continents, as in the case of Atlantis (since Plato) and more recently Zealandia (Sutherland 2017), or the search for the real Ithaca (Bittlestone et al. 2005), a considerable part of the literature as well as technological and methodological developments focuses on searching for assumed geographies. Assumptions about the existence of phenomena and their geographies are based on deduction from what is already known, on induction from experiential information, or on less rational ways of knowing.

The geographical information on which such publications focus can remain undiscovered for many reasons, like so far unmeasurable, historically distant, highly subjective phenomena, or from a lack of interest in geographies of these phenomena. Most of the examples from the literature mentioned in our chapter actually present the results and the act of revealing such assumed geographies.

As long as the focus is on assumed geographies or on methods and technologies designed to reveal these geographies, the latter remain undiscovered. Once a geography is revealed and published, this technically means that it is no longer hidden. However, even focusing on such cases indirectly reminds us of the existence of undiscovered geographies, at least in two ways: a geography that is now being revealed was previously undiscovered; the revealed geographies often represent intensively changeable geographies and will therefore soon—perhaps already at the time of publication—be outdated and undiscovered/hidden again.

Remote Sensing, Re-interpreting Throughout the history of geographic discoveries, new ways of geographic data collection, analyses, visualisations, (re-)interpretations of available knowledge and similar advances have been close to the core of activities aimed at revealing so far undiscovered geographies. Today rapid development of remote sensing and geoinformatics, in general, plays important role in bringing perpetual geographic discoveries.

Remote sensing essentially aims to reveal hidden geographies (including the renewal of existing data) detectable on the Earth’s (or another planet’s) surface, with some techniques able to penetrate to specific depths below the surface (e.g. soils, water bodies) or above the surface (e.g. atmospheric phenomena). Numerous publications and online services demonstrate the usability of such information in scientific, professional and everyday situations. A very typical example of publication that announces the revealing of still (at the time of publication) undiscovered geographies with remotely sensed imagery is presented by Posada-Swafford (2005) reporting on a joint NASA-Costa Rica project. Using multiple sensors, from high-definition infrared cameras, subterranean sensors, a radar laser to detect the thickness of the rainforest and spectrometers to analyse the air—to reveal so far hidden geographies and support policies in the fields of geology, environment, urban planning, disaster prevention and archaeology.

Lu et al. (2017) emphasise the importance of a seemingly old-fashioned remote sensing technology—a historical archive of aerial photographs—in a contemporary discovery and interpretation of ancient hidden linear cultural relics in the alluvial plain of eastern Henan, China.

The availability of LiDAR data has made it possible to reveal many previously hidden geographies, especially those hidden under forests, including natural (e.g. geomorphological) and man-made features (like archaeological sites, e.g. in Štular 2011). Johnson and Ouimet (2013) report such effects of the public availability of LiDAR data in the northeastern United States. Indeed, many discoveries of historical geographies are rediscoveries of once mapped phenomena. For example, the once known geography of the Isonzo Front became at least partly forgotten, unrecognisable, even physically hidden due to physical decay and reforestation. Many remnants of the forgotten geographies are now being rediscovered using LiDAR data (Petrovič et al. 2018).

Undiscovered geographies may be revealed unintentionally, like discovering “hidden forests” representing about 10% of the dryland biomes, increasing global forest area estimates by 9% (Bastin et al. 2017), only by using different forest detection techniques and very high temporal and spatial resolution of satellite imagery.

Another way to reveal previously undiscovered geographies can be through re-interpretation of the existing explanations in a particular area or situation. Herrick (2017) deals with hidden geographies of global health, and specifically of suffering, that could be revealed if less-archetypal and non-medical spaces were included in critical medical-anthropological explanations of the production of global health. Meta-analyses of genetic risk factors of male infertility revealed “the hidden epigenetic geography of the Y chromosome” and provided evidence for its association with ethnicity and geographical region of the tested population (Navarro-Costa and Plancha 2011).

Internet Geographies Pickren (2020) argues that the internet actually produces geographic space (internet geographies) and has a particular impact on people and places. This means that it not only plays its role in revealing hidden geographies, but produces new ones that may remain hidden e.g. due to the inaccessibility of the internet (to some people) and the increasing inability to cope with over-informatisation. Fraser (2019) discusses digital geographies, data colonialism and their relationship to critical data studies. Better understanding of the impact of digital on existing geographies, including reshaping many of them, mediating the production of geographic knowledge and reconfiguring research relationships, can be linked to a better understanding of rapidly growing and usually hidden digital geographies.

Some additional examples of revealing undiscovered internet geographies are presented in Sect. 5.

3.2 Uncognised Geographies

Undiscovered geographies obviously cannot be cognised, and could, therefore, be part of uncognised geographies. Our decision to limit our discussion of uncognised geographies to those that have been discovered, emphasises the division between undiscovered geographies that cannot be cognised and discovered geographies that could be cognised, but are not.

Cognition of a geography may be constrained due to the lack of relevant information and the personal ability to bring it to a higher level of cognition,Footnote 4 from basic data to knowledge or even higher, to its creative application. In a narrower sense, geography is revealed to someone when he has reached the knowledge level, which is the lowest cognitive level in Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson et al. 2001). This enables him to learn the facts, remember them, without necessarily understanding them. However, only the comprehension level (or higher) involves understanding, summarising, generalising the facts learned; and application level allows the acquired knowledge , facts, rules to be applied in new situations and in solving problems. Which level is better suited to separate hidden and revealed geographies remains a question of further debate. In our opinion, this decision should be situation-specific: de facto revealed geography , at the lower level of knowledge , may function as revealed if we only need to repeat it, e.g. when passing on information to someone else. In case we need to relate this geography to other phenomena in the landscape or use it in spatial decision-making, a higher level of cognition will be required to make it functionally revealed, otherwise this geography will remain functionally hidden.

Unpublished and deliberately hidden geographies (discussed in the following two sections) may be considered as subsets of uncognised geographies, the latter representing the broadest understanding of the concept in relation to discovered but hidden geographies. Such a wide, cognition-based understanding of the concept considerably expands the pool of examples from which we can learn in our attempt to uncover the horizons of its possible meanings and uses. Topics related to uncognised geographies in the reviewed literature range from legendary places, placeless places, places hidden due to lack of knowledge or attention, personal geographies, sense of place, geographies of deprivation, immigration, gender, historical and forgotten geographies, social and economic geographies, hidden geographies revealed due to methodological or technological developments, hidden geographical assumptions, or hidden geography used as a figure of speech.

Legendary, Imagined, Mythical, Religious, Sacred Some legendary, mythical, imaginary places may not exist in reality because their main function is symbolic or spiritual. But some of them have a physical existence and location. For Said (1979), imagined (or imaginative) geographies relate to the perception (of the real world) and power of those who construct descriptions that influence perception. Both conceptions of imagined geographies, as imaginary and as perceived, are embedded in oral traditions, rituals, allegories; they are more interwoven with real landscapes and lives than we may realise.

Religious, mythical, sacred places or worlds/realms often remain unseen, hidden, even secret—either associated with religious experience or organisation, hidden geographies within religious buildings or within people’s homes (Flood 1993). Imaginary (as well as more materialised legendary or mythical) landscapes are also very common in literature, art, and popular culture.

A geography of paradise, a mythical place Shangri-La, for “spiritual accomplishment and renewal” of a Buddhist, turned into a revealed geography as late as in 1998, as Beyul Pemako, “Hidden-Land Arrayed like Lotuses”, in Tibetan Tsangpo Gorge (Baker and Dalai Lama 2004; Baker 2016). The place was famous, but its geographical location was obviously a secret, deliberately hidden from the general public.

Every culture, including contemporary ones, produces new places that are given special meanings, some of which remain hidden to the cognition of many people. The search for sacred in the landscape, the recognition of spiritual, sacred places and their use as ritual sites has also been practised by all civilisations since prehistoric times. Revealing such hidden geographies, “sacred geography … embedded in the landscape” (Devereux 2010), by learning to look through the eyes of our ancestors, can bring interesting insights into the historical relationships between man and nature, as well as contribute to a better understanding of the historical spatial behaviour and human-driven processes in the landscape.

Inaccessible to Senses and Cognition, Placeless, Restricted, Lack of Attention, Out of Sight In contrast to deliberately ignored geographies, there are places or geographies ignored simply because they are inaccessible to the senses and cognition. Many texts on place-related peculiarities, which are often exposed as tourist attractions or discoveries, reveal such geographies, as curious travel destinations, “World’s hidden wonders” (Foer et al. 2016), improbable places (Elborough and Horsfield 2016), cursed places (Le Carrer 2015), “enacting Northern European peripheries” that have so far been almost untouched by globalisation and tourism (Bærenholdt and Granås 2008), camel wrestlers in Western Anatolia as carriers of the “geography of a hidden cultural heritage” (Çalışkan 2009) and the exploration of the Arctic and the dissemination of geographical knowledge from indigenous’ narratives of the Beaufort Sea (Martin 2020).

A place is perhaps simply unperceived because it lacks—in the eyes, reason or in the heart of the observer—its own place-defining character that would distinguish it from other places. Placeless (Relph 1976) places can particularly enrich the concept of hidden geographies because they refer to places of which we may know the location, or even know what they look like. But it can easily happen that we are not sure if this is the right place or if it is another one that looks and feels just the same. Hiddenness in this case has a special connotation, which has to do with disconnecting from our feelings and also from reason, consequently also from a deeper memorisation. Such places are not off the published maps, but they may be off our mental maps, or only slightly connected to them. The concept found its echo especially in the geographical and architectural literature and brought many illustrative terms and aspects such as geography of nowhere (Kunstler 1993), non-places (Augé 1995), indifferent sameness (Casey 1998), “traveling from nowhere to nowhere” (Bonnett 2014: xi).

Our cognition of places may be hindered by political, military or other restrictions. Rajaram and Grundy-Warr (2007) explore hidden geographies of borderscapes, connecting empirical, everyday procedures, with political, state sovereignty context. Border is shown “as a moral construct rich with panic, danger, and patriotism”, with daily practises with migrants calling for questioning justice and its limits.

The phenomena and their geographical distributions may remain inaccessible to senses and cognition due to lack of attention or personal interest, or external distractions. Hidden Journeys Project (2012) motivated the participants to use any of the presentation techniques (from photos and paintings to written descriptions) to report on their geographical exploration during their flights. Avoiding missed opportunities to discover so far hidden geographies (at least hidden to certain individuals) does, of course, not only refer to situations during the flight. But rarely does local observation from the ground provide such an overview of the spatial distribution of a phenomenon as from an airplane.

A particular variant of geographic hiddenness refers to phenomena that are physically out of sight. Examples can be found in relation to each of the four sub-categories of hidden geographies. Even many published geographies remain uncognised due to this circumstance. Subsurface phenomena, with their subsurface (underground/subterranean or underwater) geographies, represent a highly illustrative variant of such hiddenness. Subsurface geographies refer, for example, to soils, underground escape routes, lead mines, karstic caves, underground waters, underwater infrastructure; some of these are presented elsewhere in this review.

Lack of Knowledge Among several reasons why even a revealed geography may remain partially or even completely hidden from our cognition are deficient geographic knowledge and skills. Although such cases are not explicitly mentioned in the reviewed literature, examples are easy to find in our everyday practises. A common example is when we receive information relating to a particular place whose position we do not know exactly. Subconsciously, we may only remember its macro-location, e.g. the continent or a country. If we are interested enough, we could search for the missing contextual and geographic information. Otherwise, the memorised geographic information in such an inappropriate spatial scale remains partially or almost completely hidden from our cognition, and remains rather unusable.

A similarly common example is the national border line, which is drawn on maps and as such is not deliberately hidden from people. However, it is often not clearly visible in the landscape and its exact position may be unknown to a person crossing it. Existing information, even a potential punishment for crossing such a line, does not solve the problem of missing, incomplete or erroneous cognition. Such a geography (of a borderline) may indeed be hidden to a person and have consequences for his spatial behaviour and quality of life, regardless of why this spatial information was hidden for his cognition.

Geography is often understood as revealed when the information about it is published. Even if it seems to be a rather simplistic and unnatural principle, it can be found in all possible situations of our lives. Take the borderline discussed above: you are punished because the information about this line is published somewhere and it is your responsibility to find out about it. Similarly, when driving, you are expected to be familiar with national/local traffic regulations. Geography students are often expected to know everything that is shown on maps or in textbooks they use in a course. The fact that a particular geography is revealed to them through publication is sufficient to expect them to be familiar with it. In fact, several social, cultural, economic, political rules function this way, depending on the geographical specificities. The argument “did not know because I am not from here” is usually not enough to avoid conflict or even punishment.

Hidden to Majority, Local, Personal, Experiential, Emotional Geographies of phenomena present in our environment may be known to those who are in direct contact with them or live in the area where they occur, but they are unknown, hidden from most others. These are actually very common examples of the concept. In terms of spatial scale, they usually represent phenomena that are known locally or regionally, but are hidden from the rest of the world. Examples include hidden geographies of de facto stateless enclaves in India and Bangladesh (Shewly 2017), people living on “no man’s land” between national borders (Bonnett 2014), religious creativity in West London faith communities (Gilbert et al. 2019) and spatial dispersion of the immigrants in Louisville and across the USA (Klayko 2015).

Individual geographies, including the (spatial) behaviour, movement, emotions of the individuals, or their sense of place, are hidden from most other people. Several authors focused on personal geographies (Harmon 2003), places of belonging (Hooks 2008), hidden geographies of spatial belonging, inclusion and exclusion (Morgan 2000), emotional geographies (Davidson et al. 2007), senses of place (Eyles 1985), topophilia, topophobia (Tuan 1977, 1990). But only a few, explicitly, discussed the hiddenness of such geographies.

Lucherini (2019) discusses autobiographies as a way to revealing (personal) hidden and emotional geographies, focusing especially on the lifeworlds of people with type I diabetes. Although the author recognises autobiographies as crucial sources for studying everyday life experiences, including their spatial dimension, many everyday problems and concerns related to illness remain hidden. A hidden geography of electoral behaviour is explored by Arrington and Grofman (1999). The electoral preferences of individuals and local communities may differ from real electoral decisions because “voters have an incentive to vote strategically”. Such “hidden partisanship” is reflected in the geographical pattern of election results, and in its more difficult predictability.

A hidden geography can be something we experience, even participate in its functioning, without seeing the bigger picture, the geographical spread or the spatial density of the phenomenon. Once again, this is one of the frequent, and at the same time disturbing examples of hidden geographies that reveal our geographical ignorance of our directly experienced lives. Labour migrations from the new EU member states to the UK have been statistically observed and perceived by people in contact with the actual process. But it is only the evidence of discrepancies between Worker Registration Scheme and the allocation of the National Insurance Number that reveals the hidden geography of self-employment and entrepreneurial activity of these migrants, with their considerable concentrations also in urban, and not in (expected) rural and peripheral areas (Harris et al. 2015). Another surprisingly intensive process, a dynamic hidden geography of booming alternative food networks and the establishment of farmers’ markets in and around Prague, is revealed by Fendrychová and Jehlička (2018).

Deprivation, Marginalisation, Exclusion, Immigration Geographies of deprived, disabled, marginalised individuals or social groups are usually hidden and coincide with problems of their inclusion or exclusion. Matthews et al. (2000) point to hidden, alternative geography of exclusion and disenfranchisement of children growing up in rural areas, emphasising “the sharp disjunction between the symbolism and expectation of the Good Life … and the realities and experiences of growing-up in small, remote, poorly serviced and fractured communities”. Hall (2004) explores hidden social geographies of people with learning disabilities, “one of the most marginalized groups in society”, their exclusion from and integration into mainstream socio-spaces, and their creation of safe spaces formed by themselves. Larreche and Ercolani (2019) show the nocturnal geographies of the LGBT scene in Bahía Blanca, Argentina, “complex cartographies that involve aspects of spatial prestige, internal tensions and microcultural fixations”. Buzar (2007) reveals hidden geographies of deprivation, based on energy poverty in the post-socialist Eastern Europe, and Betto et al. (2020) on measuring energy poverty in Italy. Hidden geographies of the changing lifeworlds of women with multiple sclerosis (Dyck 1995) refer not only to concrete places and their distribution (as we have basically defined one of the possible meanings of geography), but also to abstract and generalised representation of their spatial behaviour, specificities of and obstacles to their spatial movements and similar.

Lawrence (1995) unmasks the hidden geography of rural homelessness, which exceeds the intensity of the phenomenon in urban areas (the study was conducted in the USA), and questions representations of rural space as “especially emphatic in their valorization of privacy, property and independence”. In a study on the hidden geography of immigrants at risk of homelessness in Vancouver, Fiedler et al. (2006) use hidden to refer to the visual concealment of immigrants and their hiddenness to the statistics (because they have housing, but the cost of which exceeds their income), hidden spatial distribution of their homes, as well as ignorance of public policies to meet the housing needs. Wu (2008) examines the hidden geographies of everyday practises and the creation of social identities of Taiwanese migrant women in Toronto, looking at their “everyday language practice, the reconstruction of food culture and the exploration of culinary practice, the negotiation of home practice, and the creation of new spaces for new identity claims”.

Gender Hidden gender geographies are very persistent, often a part of traditional social relationships “as they always used to be”. Townsend (2002) discusses the hidden geographies of women’s lives on Iberian farms in the 1990s (in relation to the publication of the results of a grounded research by Garcia-Ramon et al. 1994). These women’s multiple functions are poorly paid and often not visible in any statistics. Some of their activities are defined by local cultures (at home, as mothers), activities on the farm are understood as help, not work, and additional obligations include their work outside the farm, often at home or seasonally. As a result, their hidden lives are “cyclical and discontinuous” in comparison to the lives of men, which are “linear and accumulative” and visible.

Historical, Forgotten Hidden geography can be a result of historical processes that are lost to today’s observers as forgotten geographies, partly due to physical decay, re-vegetation or other types of landscape changes, as well as the lack of information, collective memory, or awareness of these processes. In his reflection on the Royal Geographical Society’s exhibition, Driver (2012) reminds us that when we look at the history of exploration, referring to times when many hidden geographies were revealed, we must expect to be confronted also with hidden histories, which rise questions such as “what is made visible and what is obscured in standard narratives of exploration”. Known facts about cooperation of individual Czech modernists with their colleagues in Vienna and Berlin from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century are transformed into revealed geography of the cooperation of Czech modernists (David-Fox 2000) only with a cultural-geographical interpretation of them collectively. The hidden geography reveals itself through generalisation by taking a broader view of the subject. Walker (2001) points to the “geographic magic done by the hand of nature and humankind” in and around Golden Gate, which can be seen in remnants like “dots of brick and mortar tucked into the coastline” that can only be reconstructed by calling them up “from hidden places of collective memory”. Another example of hidden historical geographies deals with a complex system of underground drainage channels in the lead mines of Derbyshire, created between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries to enable mineral extraction. It not only had a major impact on the need for original legal solutions related to vertical conceptualisations of space, but also contributed to a “vertical turn”, and volumetric turn, in geography to deal with subterranean landscapes appropriately (Endfield and van Lieshout 2020). The concept of hidden geographies has been used here in at least two ways: historically, by being revealed and renewed a few centuries ago; and rediscovered, reawakened from oblivion in contemporary literature. Stuart (2010) reveals hidden geographies behind the “remaking of the river in accordance with the requirements of capital”, including a number of overlapping administrations, regulatory organisations, the establishment of system of locks and other engineered resolutions to the conflicting uses of the river Thames since the seventeenth century.

Economic and Social Many examples can be categorised as hidden economic or social geographies. Community economies in South-East Asia, which include “pre-capitalist”, “relict practices” such as mutual aid, reciprocity and sharing as predominant features of everyday community life, are “seen as standing in the way of modern economic growth”, but in reality “contribute to local social safety nets and act to support households” in times of difficulty (Gibson et al. 2017). Murphy (2007) reveals the “materiality of computer mediated retailing”, hidden geography of e-commerce, how a “seemingly simple act of doorstep food delivery is explicated in urban form, and in transportation and communication infrastructures”. Looking at a city through the eyes of burglars brings quite a peculiar socio-economic-geographical perspective to hidden geographies (Manaugh 2016).

Problem of Definition, Reinterpretation, Methods Hidden geography can be the result of methodological problems in defining the spatial extent or position of a phenomenon, such as the borders/margins of settlements (Krevs 2005; Benchetrit and Stadnicki 2014), the shape of buildings (Ai et al. 2013), or even more fundamentally, the phenomenon itself, such as the definition of urban settlements and resulting geographies. Van Duijne (2019) reveals hidden urbanisation in India, which is due to the politicised process of rural-to-urban settlement reclassification, influenced by village leaders who resist being absorbed by the expanding cities, resulting in consequent effects on urban policy. Specificity of this use of the concept of hidden geography is based on the controversial imposition of an external (e.g. by experts, politicians) explanation of the real geography, which is different from the geography people know and live with. Imposed geography is not merely theoretical, but has concrete consequences for people’s lives that are not necessarily positive for them. The external imposer actually initiates the transformation of a known geography into a new one, which was previously at least partially hidden from the people’s cognition. At the same time, the real geographical process is obscured by an administrative model of reality (e.g. on a map) and, at least from this point of view, becomes partially hidden.

Revealing previously hidden geography can be based on complex (geographical) analyses, such as in a study on the transformation of invisible spatial patterns into maps of wind dissipation and wind energy potential (Kılıç 2019). Liu et al. (2018) used complex machine learning techniques of spectroscopy and chemometric data to efficiently discriminate the geographical origin of extra-virgin olive oils, Deng et al. (2020) similarly analysed chemometric data to discriminate the designated geographical origin of tea and Maione et al. (2019) the geographical origin of honey. These examples aim to confirm a known or assumed geography. It is only when a fraud about the geographical origin of products has been uncovered that a previously hidden (false or fraudulent) geography is revealed.

Hidden Geographic Assumptions, Models One of the rare examples of hidden geographies that refers to geography as a discipline was found in a critical discussion by Agnew (1995) on the geographic terminology and models in the social sciences. Agnew argued about the hidden use of inevitable geographical assumptions, “powerful unconscious geographies” (italicised by the author of this chapter), that undermine the characterisations of the social sciences as “spaceless”, the dangers of over-commitment to fixed geographical models and fixed spaces as containers of society.

Figure of Speech Authors can use hidden geographies, or paraphrased, e.g. as hidden worlds, to illustrate something known to certain people (e.g. scientists in a certain field, local population), but is supposedly unknown to the audience they are addressing. For example, as in “explore nature’s mysterious hidden worlds” (2019), the authors emphasise nature’s hiddenness to the knowledge of some people—used as a figure of speech to obtain a particular narrative effect, and not necessarily related to geography.

3.3 Unpublished Geographies

Unpublished geographies are considered a subset of uncognised geographies. When geographical information about a discovered phenomenon has not been made available to the public, either in visual (e.g. on a map), acoustic or other forms accessible to the human senses and perception, it remains also inaccessible to individual and collective cognition. The public does not have to include everyone, but only those who are interested, which potentially contributes to the relativity and vagueness of the conceptualisation.

A subset of unpublished geography, the off-the-map-based understanding of a hidden geography, refers to phenomena that have been omitted from maps. In this manner, Bonnett defines hidden geographies in relation to places that don’t appear on maps, and as the inverse of lost places (2014: 37), or non-existent places (ibid., 3), which appear on maps, but can’t be found in reality.

Several topics relating to unpublished geographies in the reviewed literature are presented in the adjacent sections, under uncognised and deliberately hidden geographies. Of course, examples of unpublished geographies are hard to find, so we refer to circumstantial evidence—previously hidden and eventually revealed/published geographies. Among such examples are geographies unpublished due to stigmatisation or ignorance, and geographies of phenomena that are not permanently located.

Stigmatisation, Ignorance Ignored geography can refer to stigmatised phenomena such as the suicide rate, and occasional publications can appear as the discovery of a hidden geography (Florida 2013), which they are for those who are not aware of it. A similarly avoided issue, “underpolicing” of rape in parts of US cities with the majority of the African American population, is highlighted by Brownlow (2017) in a case study in St. Louis.

Van Schendel (2002) contrasts the production of the “geographies of knowing” with “geographies of ignorance” by emphasising the focus of analyses on certain areas, while (consciously) ignoring the others. South Asia belonged to the latter, being dispensed after the Second World War, became peripheral and consequently the growth of knowledge about it slowed down.

No Permanent Location Places can be hidden and their geography unpublished just because they are not permanently located on the Earth’s surface, such as “floating places”, including floating islands and luxury cruise ships (Bonnett 2014). Or they are constructed and planned to be used only for a limited time (but can remain for a long time), like “ephemeral places”, from improvised townships for refugees, temporary workers, occasional festival towns, to “dogging places” (ibid.).

3.4 Deliberately Hidden Geographies

The deliberate hiding of geographies is something that human societies and individuals have practised throughout history. Today the reasons for this may not be so different from historical ones; they range from gaining strategic advantages, as in military or economic situations, to other kinds of selfish prestige. Maintaining security and protecting places defined as special in a given society or by an individual are also among the reasons for actively hiding geographies. Even the reasons that we might regard as rather modern, such as the preservation of vulnerable natural or cultural phenomena, have been used in history and increasingly so today.

With the development of methods for the collection and dissemination of geographical information, the methods of its active hiding have also changed. However, the basic principles of hiding are still similar: either by hiding the geographical information from others by keeping it unpublished, by misleading publication, by physically or legally restricting access to the hidden places, by physically hiding or camouflaging objects or by urging not to go/to search further (e.g. by scaring away).

In our model (Fig. 1), deliberately hidden geographies are a subset of unpublished geographies and the most specific case of discovered but hidden geographies. In the above list of basic principles of hiding geographic information, an exception to this hierarchy is mentioned: deliberate hiding may involve publishing when misleading or incomplete geographic information is published.

Examples of deliberately hidden geographies are as difficult to find as unpublished geographies, even in the cases just mentioned, when they are published. The following examples mainly show situations where such geographies become revealed, or where access restrictions contribute to hindered cognition of these geographies. The topics relate to issues such as violence and fear, deliberate ignorance, restricted information/access, environmental issues, protection of personal data and deceptive geographies.

Violence and Fear A historical example of hiding to survive is presented by Schmid (2020), revealing hidden places and metro underground tunnels in Brooklyn on the way of Missouri slaves towards freedom. A specific part of the literature deals with hidden geographies related to violence, wars, especially civil wars, genocides, mostly coupled with geopolitical interests of the economic and military world powers. Such a deliberately hidden and (internationally) ignored human geography of the Congo is illustrated by Wanzola (2013), which highlights some of the most important immanent injustices of the modern world. The hidden geographies of informal power in the Greater Middle East (Anceschi et al. 2014), a perpetual playground of the world’s superpowers throughout the history, are another example. Allouche (2019) discusses visible and hidden forms of violence related to state-building, nation making and post-colonial hydropolitics in India and Israel. War-induced hidden geographies can refer to long-lasting historical remnants of war, such as unexploded bombs (e.g. Mombauer 2017). Radio station Slovenia 1 (https://radioprvi.rtvslo.si/) reported such news about discoveries of the bombs from the 1st or 2nd World War almost daily, as recently as until 2019.

Hidden geographies of violence and crime do not always have political origins. Percy-Smith and Matthews (2001) reveal the hidden geographies of fear, “tyrannical spaces”, “no-go areas” in urban neighbourhoods due to bullying of young people in a selected British town. The problem of urban violence, which also involves other age and social groups, is a rather global phenomenon and is often swept under the carpet by local authorities, keeping this geography hidden, which is contrary to the benefits of the (local) population. Geographies of violence and fear do not have to be related to people alone. Bloch and Martínez (2020) report on geographical analysis of dog killings by the police in Los Angeles. The problem “remains largely unknown and all but completely absent from the academic literature on state violence”, which the authors attribute in their study to the concentration of the canicides in low-income areas and African American communities.

Restricted, Military Geographies Military sites and activities are usually hidden from the public around the world. Even in cases of their very obvious physical presence, e.g. in settlements inhabited by non-military residents, there are restrictions on access, photographing or sometimes even mentioning them in public communications. When confronted with deliberately hidden geography, such as trespassing a military zone or a place of illegal activities, this can have unpleasant, even dangerous consequences.

The military uses a very illustrative term to describe the areas that remain hidden to an observer due to intervening obstructions, including natural and man-made obstacles: dead ground (Salovaara-Moring 2009). An example of hidden military geography is revealed by Paglen (2006) which refers to the “black world” consisting of secret military bases north of Las Vegas. Some activities there are “so highly classified their very existence is a state secret. For public purposes, they do not exist”.

Secrets are not necessarily limited to military installations and activities, but also to their environmental and social impacts, as in the study of nuclear landscapes and indigenous inhabitants in the south-western United States (Kuletz 1998). Environmental issues, such as climate change, can be related to military secrets also in other rather peculiar ways, as exemplified by the Cold War military base Camp Century (Colgan et al. 2016). The intention to remain hidden forever deep in the ice sheet in Greenland has failed as the melting ice will bring it to the surface in the next 75 years. The revelation refers not only to the visual aspect, but also to the “remobilization of physical, chemical, biological, and radiological wastes abandoned at the site”.

Environmental Issues, Exceptional Natural and Cultural Goods A large area of intentionally hidden geographies is related to environmental issues, such as pollution and its impact on public health and the economy. Studies of air pollution with fine particulate matter (PM2.5) have shown its strong link to fossil fuel combustion, but little is known about the “socioeconomic factors driving the growth of PM2.5 emissions, which has been hidden from the public due to the geographical separation of production and consumption activities”, revealing physical PM2.5 emissions along supply chains to the consumers (Yang and Chen 2017).

Natural and cultural assets of exceptional value and vulnerable social groups can sometimes become protected by restricting access to them or even hiding their location. This may often be the only way to protect them effectively. An example of the hiding of exceptional, vulnerable natural assets for their protection are the so-called “hidden caves”, which are described by the Underground Caves Protection Act (Zakon… 2004) as “caves in which the natural cave environment is so vulnerable that it could be damaged or endangered by any entry of persons into the cave”. To enter these caves, you need a special permit from the Ministry of the Environment. Their locations may be known to speleologists and the local population, but on the public portal of the world’s first online Cave Cadastre (https://www.katasterjam.si/) you will not have access to the data about these 5 (out of 13,659 registered) caves.

Hide our Place: Social Network Discussion About Living on One of the Islands in the Adriatic Sea, Originally in Croatian

Thread by local 1: it is so beautiful here

Non-local 1: you do not know that you live in paradise!

Local 2: we know, don’t tell anyone

Local 1: yes, it is our secret!

Local 2: we have known this since forever

(Facebook, hidden link, accessed 30 October 2020)

Personal Data Protection An obvious case for hiding geographies is the protection of privacy of people’s movements across space. After decades of increasing misuse of personal data, people are becoming increasingly sensitive to this problem. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, countless online debates criticised the use of mobile applications that use spatial information about people’s movements, even though they could help to detect and warn of occurrences of encounters with infected people.

Lies and Deceptive Geographies Many cartography courses include books like How to lie with maps (Monmonier and De Blij 1996) into the essential reading lists. Hiding geographies by omissions, deceptive representations, or the inclusion of false information on maps, or in other media, can be intentional or accidental. For example, a geography may be deceptive due to poor ability to read maps or due to the use of the received geographical information at a higher cognitive level, not just by an intentional act of hiding.

In a time of the COVID-19 pandemic, the chaotic flow of information from official institutions brought frequent expressions of doubt about the reliability of the information. Fears, perhaps justified, that this flow of information, which changed our lives so drastically in just a few weeks, also contained many fake messages—“deliberately false”, “misleading by design”, “manipulating the audience’s cognitive processes” (Gelfert 2018). Even if this was only partially true and the mistakes were the result of lack of knowledge and methodological clumsiness, the data were heavily mapped and contributed to questionable geographical representations and cognitions of a real spatial process, which probably remained hidden.

4 Defining Hidden Geographies

Learning about the concept examined in the chapter so far has revealed a wide range of its possible meanings and uses. A summary of the characteristics of the concept is presented and briefly discussed in order to support a critical, better informed argument about hidden geographies, followed by an attempt to propose a definition of the concept.

4.1 Summarising the Characteristics of Hidden Geographies

After meandering between different instances of the concept, a simple Aristotelian approach based on elementary questions seems appropriate to organise what we know.

What is hidden The most general view of the object of hiddenness represents two fundamental aspects of what geography means, geography as a discipline and as the spatial location/distribution of a phenomenon.

Geography as discipline, geographical modes of representation, argumentation and interpretation, including geographical models and assumptions used in scientific and everyday discourse, are often discussed in the literature. However, there are rare attempts to view them in the context of hidden geographies.

Hidden geographies as a spatial aspect of phenomena refer to individual places and their absolute or contextual location or to multiple places and their absolute or contextual spatial distribution (as defined at the beginning of the chapter in Sect. 2.1). Geographies can refer to material/physical and non-material phenomena. Phenomena and their geographies can be the result of imagination, beliefs, reasoning (e.g. in extrapolations of known facts or speculations). Some such imaginary geographies may be mapped (and have been mapped in the course of history), and therefore, their hidden opposites may be considered a special kind of hidden geographies.

Hidden by whom and to whom Who can refer to the provider, the recipient and/or the carrier/user of information about a hidden or revealed geography. These roles can be performed by individuals or collectively, by institutions, social groups, societies.

When we think about a collective, shared group-specific/social/civilisational knowledge (about the geography of a phenomenon), we use a rather abstract way of saying who actually knows. We allude more to anticipated than to actual knowledge, by pointing out that a particular group/society has been informed, e.g. by making certain information publicly available in a way that is expected to be received and cognised by all. In the reviewed literature, as well as in occasional debates among geographers (e.g. at a conference on this topic, Hidden Geographies 2019), such a collective, abstract understanding of the concept seems to have prevailed in practise so far.

When a geography is intentionally hidden, the concept of hidden geography gets a particular socio-relational emphasis. The hidden place exists, and someone (or several people) knows about it, but prevents access to this information or simply does not communicate it.

Why is it hidden Among the many reasons for the hiddenness of geographies presented in this chapter, the following cover the majority of situations. Geographies are hidden before they are discovered. When discovered, they may remain hidden due to deliberate hiding or insufficient cognition. The reasons for deliberate hiding range from selfish, e.g. acquiring a particular personal, social, economic, political, military advantage, to altruistic, e.g. to protect fragile natural or man-made goods. Insufficient cognition (insufficient to reveal a geography in a given situation) may be the result of ignorance, lack of attention or interest, sensory/perceptual deficiencies and other obstacles/disruptions in accessing the geographic information. Even when the geographic information is received, cognition may be insufficient if there is a lack of prior geographic knowledge and/or the ability to think geographically. Among the main sources of hiddenness of geographies are also the following two processes: forgetting (as individuals or collectively) and the difference between real geography and known geography as its representation, both processes usually increasing over time (as discussed in more detail below).

How is it hidden What must be missing to get a hidden geography? The most basic reason for the existence of a hidden geography is that it has not yet been discovered. The next basic step, the lack of access to raw data or information (such as a map) about the geography of a phenomenon obviously prevents its revealing. Geographies can be hidden intentionally or by providing false, misleading geographical information. Finally, published, even online ubiquitous geographies can also remain hidden due to insufficient geoinformation abilities or cognition.

When we obtain spatial data about a phenomenon, various outcomes are possible. If our knowledge allows us to effectively use the data, cognitively transform them into a revealed geography, then the geography is no longer hidden to us. In all other situations, it remains at least partially hidden, even completely hidden to our cognition in case we have no spatial knowledge to help us use these data.

As discussed, an individual has to reach at least the basic knowledge level of Bloom’s cognitive taxonomy in order to memorise and transfer a learned geographic information. If we are not able to use this knowledge in our reasoning and activities, the situation is practically comparable to that when geography is hidden from us. We only possess the isolated knowledge in a rather unusable form.

In order to be able to use the acquired information more competently in solving problems, spatial decision-making and similar, at least the comprehension level has to be acquired, or higher. Effectively linked knowledge (about a revealed geography) enables us to actively use it, whenever needed, even in new situations. Therefore, at this or higher cognitive level, we can also link the revealing of a previously hidden geography with personal spatial or geographical abilities that enable a person to function spatially in an efficient way.

When is it hidden The apparent dualism in the use of the phrases hidden geography and revealed geography suggests that a hidden geography ceases to exist when it is revealed. However, from a cognitive-based perspective, both phrases denote very blurred and transient phenomena. Transience is characteristic of both the phenomenon/landscape and our knowledge of revealed geographies, for different reasons, as illustrated in a life cycle of hidden geographies (Fig. 2). The knowledge is only temporary and may gradually fade (through forgetting) and/or become increasingly inaccurate due to the changes in the real landscape. Over time, the hiddenness of a geography tends to increase and even predominate. Within the inner life circle (marked 2B in Fig. 2), hidden geographies are not only a consequence of hiding information from potential recipients, but also of their willingness and ability to perceive this information and bring it to a higher level of cognition.

The hiddenness of a geography can be quite persistent. When it is revealed (to someone, to certain people, even to the general public through publication), it remains hidden to some people. When it is revealed to someone, it may further remain hidden to his perception (e.g. in case he does not pay attention to this information) and his cognition. This could be due to that person’s lack of spatial, cartographic and geographical knowledge and abilities, but also to situational circumstances such as stress or external distractions. Information is revealed, loses its hiddenness, but does not necessarily reach higher cognitive levels to become usable. As a result, it may be poorly understood, stored and transmitted.

Spatial knowledge is often unreliable and transient. When we learn about a geography that is not related to our personal experience, like in case when it is related to some distant landscapes, the mental images and cognition of such geography are rather abstract and may only seemingly correlate with real geography. Even when crossing experienced places, which are often local and closer to human perception, people can get lost due to incomplete or otherwise unreliable mental maps, perhaps combined with a lack of attention. When a real geography changes, people may retain a mental image of the earlier, less and less correlated landscape. Besides, they may also be unaware of this change. Known geography tends to discord with the real geography of a phenomenon, and therefore, the former becomes false (or at least partially right) and the latter becomes hidden.

In summary, the changeability of real geographies, the fading of knowledge of a known geography due to forgetting, the loss of bits of the original information, the addition of new bits that can change the original information, and other factors that determine the adequate correlation between real and known geographies contribute to the following conclusion: hidden geographies obviously have a tendency to overshadow the knowledge of real geographies.

Where is it hidden Even a hidden geography has a geography of its own. Where can relate to the place/space referred by the hidden geography, or to the distribution of those who know (or do not know) about this geography.

When studying deliberate hiding of geographical information, then the geography of hiddenness strongly relates to the spatial distribution of those without access to the information.

Exploring the hiddenness of geography as a discipline may focus on the geographical way of thinking, and geographic/geoinformatics abilities, which may correlate with (spatial) differences in the existence of geography education and training, or its different success in transferring geographic knowledge and skills.

The spatial dimension of the concept is, therefore, a result of the geography of a phenomenon, and the spread of the information and knowledge about it. These are not necessarily correlated. A phenomenon may be located at a single point on the Earth’s surface and well known to the majority of (e.g. informed, educated) population. A phenomenon may be spread globally, but remains hidden from everyone, or from the majority. Information about a phenomenon and its spatial distribution may be diffused in relation to the distance of the people from where the phenomenon is located, or with almost no relation to it. The geography of hiddenness of a geography (of a certain phenomenon) can, therefore, often be quite complex and unpredictable, even in times of ubiquity of geographical information.

4.2 Definitions

Looking at the continuous debates about what geography is, one cannot expect defining hidden geographies to be a one-time effort. Therefore, our attempt should be seen as a motivation for further debate rather than as something final. Several paths to understanding the concept of hidden geographies have been explored in this chapter, and some of them could already serve as working definitions in practise. In this section, we only briefly synthesise some of them in a more formal form. First, we focus on four of them, following the model of the layers of hidden geographies (Fig. 1), starting with the undiscovered geographies.

Undiscovered geography refers to an existing or imagined geography of a material or non-material phenomenon that has not yet been discovered. It can refer to the hiddenness from a particular individual or society, or to the geography of a phenomenon that has not been discovered due to the inaccessibility of the information, usually caused by lack of knowledge or appropriate technology/methodology.

Uncognised geographies are the most general of the hidden geographies that have already been discovered.

Uncognised geography is a discovered geography which is hidden from cognition.

The definition of uncognised geography is defined in more detail as follows:

Uncognised geography is an absolute or contextual geography of a material or non-material phenomenon which is hidden from cognition. The necessary level of cognition to reveal a hidden geography is situation specific and requires at least knowledge level, but normally the comprehension level or higher. When such a situation-specific level of cognition is reached, geography is functionally revealed, otherwise it remains functionally hidden.

A specific case of uncognised geography is unpublished geography.

Unpublished geography is geography uncognised due to hiding geographic information from the public.

A more detailed version of the definition of unpublished geography is as follows:

Unpublished geography is an absolute or contextual geography of a material or non-material phenomenon which has not been made available to the public in visual (e.g. on a map), acoustic or other form accessible to the human senses and perception.

The narrowest understanding of the concept in the model is represented by deliberately hidden geographies.

Deliberately hidden geography is intentionally unpublished geography, or intentionally published in such a way that its cognition is hindered.

A more detailed version of the definition of deliberately hidden geography is as follows:

Deliberately/intentionally hidden geography refers to the absolute or contextual geography of a material or non-material phenomenon that is deliberately hidden by certain people from other people. Usually it refers to the hiding of geographical information by omitting it from maps or by preventing access to maps containing this information. However, it may also refer to forms of communication other than visual.

Finally, a more general definition of the concept is as follows:

Hidden geography refers to an existing or imagined, absolute or contextual geography of a material or non-material phenomenon which is hidden for one or more reasons, e.g. because it is undiscovered, deliberately hidden, unpublished or otherwise hidden from cognition. Such hiddenness may for example be the result of ignorance or lack of knowledge, forgetting information, memorising and using outdated information while the real geography changed, as well as deliberately hidden geographies.

The above definitions refer to geography as spatial location/distribution of a phenomenon. They can also be adequately adapted to refer to geography as a discipline.

5 Hidden Geographies, Geography and Geoinformatics

One of the essential missions of geography as a discipline is to reveal, explain, interpret geographies of phenomena, and complex interrelations between them. Hidden geographies can therefore be seen as a measure of the lack of efficiency of the geographic discipline. However, this measure would not be fair or appropriate to the discipline. Among the reasons, at least the following three should be highlighted: geography and geoinformatics (including cartography) play an obviously controversial role in deliberate hiding of certain (known) geographies; the number of hidden geographies is increasing rapidly, already due to increase in the world population and the diversity of its activities; it is not the amount of revealed geographies that really matters, but rather the proportion of revealed and cognised (geographical) relevant information that we need to function in our lives and our ability to use it.

Geography, together with geoinformatics (in its broadest definition including cartography and remote sensing), has never been a mere provider of geographic information. But this area of their activities is still important and is developing rapidly, updating already known and revealing fascinating previously hidden geographies. The development includes the discovery and presentation (of geographies) of new phenomena, the use of new visualisation methods, the application of new measuring or analytical techniques and the mapping of barely measurable qualitative information. The global geographical information coverage of physical environments, mostly based on various remotely sensed data, is quite well established and is used in environmental modelling on different temporal and spatial scales. The global geographical information coverage of human activities is much less accessible to researchers or individual users and is collected and used in often ethically questionable ways (e.g. based on tracking online behaviour and spatial movements of people without their consent or awareness). However, there are attempts to retrieve useful geographical information from publicly available online sources and to provide efficient demonstrations of certain global phenomena related to human activities.

An illustration of the extreme reaches of the geoinformation technologies, which reveal previously hidden human geographies, is based on the activities within the GDELT project (Leetaru 2020a). This online platform focuses on automated, machine-learning-driven retrieval, analysis and presentation of global online news coverage in 65 languages (Leetaru 2015a). It focuses on sensing the social/media reactions to selected social or natural phenomena, revealing geographies that tend to be very unpredictable and transient and consequently hidden most of the time, uncertain, even quite soon after their revelation. The database is extensive in terms of media and the languages, although still selective. In the GDELT analysis of the languages used in the news from 2015 to 2018 (Fig. 3), more than 850 million articles referred to 6.6 billion locations (Leetaru 2018a, b). The resulting map “reminds us of just how much of the world we miss when we look only at English” (ibid.); most of the planet is covered by news media using other languages. “To penetrate into local news and perspectives”, to reveal a certain hidden geography, “one must utilize local news in local languages, making use of mass machine translation to process it all” (Leetaru 2015b). Some other examples of revealing the hidden geographies of planetary media news in the GDELT project include media responses to the Covid-19 pandemic (Fig. 4), wildlife crime activities (Leetaru 2015c), global climate change (Leetaru 2015d) and an animated map of global protest activities at the country level over the period 1979–2019 (Leetaru 2019).

A linguistic diversity of world news: a map of the languages used in media news for the period 2015–2018 (reproduced with permission, Leetaru 2018a)

Covid-19-related news from 1 to 5 April 2020: a world map of a transient geography of media response to the pandemics (reproduced with permission, Leetaru 2020b)

Under conditions of the ubiquity of geographical information, we face the problem of its efficient use, given its quantity and the lack of knowledge required for efficient handling. Knowledge relates to our personal skills and cognition and, increasingly, to procedures, many of which involve artificial intelligence built into the digital tools we use. In addition to the more traditional geographic, cartographic and spatial abilities, we are, therefore, increasingly developing geoinformatics abilities.