Abstract

The main aim of this chapter is to explain how institutional change, measured with a set of governance indicators, can support the reduction of poverty and inequality in society that is an essential prerequisite for supporting economic growth of nations. This chapter shows a study that investigates 191 countries to clarify the relationships between institutional variables and socioeconomic factors of nations with different levels of development. Central findings suggest that a good governance of institutions supports a reduction of poverty and income inequality in society. In particular, results of this study show that the critical role of good governance for reducing inequality and poverty has a effect in countries with stable economies higher than emerging and fragile economies. Overall, then, the study described in this chapter reveals that countries should focus on institutional change directed to improve governance effectiveness and rule of law that can reduce poverty and inequality, and as a consequence support the long-run (sustainable) socioeconomic development of nations.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Institutional change

- Governance indicators

- Economic governance

- Government effectiveness

- Rule of law

- Income inequality

- Equality

- Poverty

- Developing countries

- Institutional framework

- Governance approach

- Institutions

- Society and institutions

- Institutional theory

- Institutional development

1 Introduction

Social scholars argue that the development of human societies is due to good institutions that enable the definition and defense of political rights, civil liberties, and formal property rights (Aoki 2001; Bathelt and Glückler 2014; Campbell 2004; Coccia 2018a, 2019a; Dacin et al. 2002; Di Maggio and Powell 1991; Greif 2006; Kingston and Caballero 2009; North 1990; Ostrom 2005; Selznick 1996). Efficient institutions and good governance are essential prerequisites for long-run economic development of countries (Acemoglu et al. 2005; Coccia 2019a, b; Dixit 2009; Kotschy and Sunde 2017; Breunig and Majeed 2019). Economic literature reveals that democracy grants economic freedom, higher civil and political rights, and better rule of law, which support the economic growth of nations (Acemoglu and Johnson 2005; Acemoglu et al. 2008; Kyriazis and Karayiannis 2011). Socioeconomic studies focus on the relation among inequality, poverty, and institutional change, which affects the economic and social change of countries (Breunig and Majeed 2019; Kotschy and Sunde 2017; Pullar et al. 2018). In fact, high-income inequality in society leads to social conflicts and violence that can harm economic growth (Stiglitz 2013; Wilkinson and Pickett 2010; cf., Coccia 2017a). In this context, efficient institutions and efficacious institutional change, directed to poverty and inequality reduction, are important factors for fostering the appropriate functioning of economies (Chen and Pan 2019; Chong and Calderon 2000; Chong and Gradstein 2007a, b; Pullar et al. 2018; Ravallion 2001, 2002, 2016; Zou et al. 2019). The contribution here expands these research topics by asking whether and how a good governance of institutions affects poverty alleviation and inequality reduction between countries. In particular, this chapter endeavors to clarify two research questions:

-

How is the relationship between structure and governance of institutions, income inequality, and poverty across countries?

-

How structure and governance of institutions affect inequality and poverty reduction in countries with different levels of development? Is this relation stronger in emerging or advanced nations?

The response to these questions can explain the critical relationships between institutional change, measured with governance indicators, and levels of poverty and inequality in society. In short, the basic argument of this chapter can be schematically summarized as follows:

The chapter design here is based on a dataset of 191 countries. Statistical analyses seem to reveal that a good governance of institutions has a higher impact on reducing poverty, rather than income inequality in society. Specifically, this chapter shows that good governance reduces poverty both in poor and rich countries, though advanced and stable nations have a stronger effect of reduction. This result suggests that a good governance of institutions is a main policy for poverty alleviation to improve socioeconomic conditions within countries and sustain long-run economic growth. Section 2 provides a theoretical background and a brief review about studies related to these topics. Data, measures, and study design are described in Sect. 3. Statistical analyses are in Sect. 4, focusing on the interaction between indicators of good governance, inequality, and poverty, both using data of all countries worldwide and data of countries categorized with different levels of development and socioeconomic fragility. The final Sect. 5 suggests implications for the political economy of growth, based on good practices of governance targeted to reduce inequality and poverty for supporting socioeconomic development of countries.

2 Theoretical Framework

The main purpose of this chapter is to determine if and how governance of institutions affects and reduces levels of poverty and income inequality in society. The solution of this problem can lay the foundations for best policies that increase the efficiency of economic system and support determinants of the growth of countries. Firstly, it is important to clarify the concept of governance, which is basic for this chapter here. Manifold definitions about the concept of governance are present in literature (cf., Campos and Nugent 1999; Campos 2000; Streeten 1996; Dethier 1999; International Monetary Fund 1997). The World Bank (1994, 1995, 1996) has also proposed different approaches to operationalize the concept of governance for empirical studies (cf., Kaufmann et al. 1999). In particular, governance is based on vital dimensions, such as: rule of law, executive, bureaucracy, the character of policy-making process, and civil society (cf., Campos 2000). These institutional dimensions are associated with good governance if the executive branch of government is accountable for its actions; the quality of the bureaucracy is high such that it is efficient and capable of adjusting to changing social needs; the legal framework is appropriate to circumstances and has command broad consensus; the policy-making process is open and transparent so that all affected groups may have inputs into the decisions to be made; and finally, civil society is strong so as to enable it to participate in public affairs. These dimensions of good governance have complementary relationships (World Bank 1994). Secondly, it is important to discuss the main effects of good governance in socioeconomic systems, considering studies at micro level (cf., Pritchett et al. 1997; Coccia and Benati 2018) and at macroeconomic level of a single characteristic of governance between countries (cf., Ball and Rausser 1995). In general, governance characteristics affect the behaviour of socioeconomic systems over time and space. In this context, Persson and Tabellini (2003) claim that constitutional arrangements have the ability to influence economic policies and thus patterns of socioeconomic development of nations (cf., Coccia 2017e). Acemoglu et al. (2008) argue that political and economic development paths are mainly interwoven. In particular, liberal democracy (with effective legal system and political competition) can support a good governance that will translate into improved social cohesion, control of violence, and economic performance of nations (Acemoglu et al. 2008; Coccia 2010; Farazmand and Pinkowski 2006; Farazmand 2019; cf., Coccia 2017a, 2018a, b, c, d; Coccia 2019b, e, f; Coccia and Bellitto 2018).

One of the important issues in institutional theory is to analyze how the concept of good governance is associated with socioeconomic indicators to explain relationships supporting the development of nations. Especially, it is important to clarify if institutional dimensions of good governance generate stronger effects on specific factors of socioeconomic development (UNDP 1995). Overall, then, relations among good governance indicators, inequality, and poverty play a vital role for the economic growth of nations.

2.1 Governance and Inequality in Society

Kotschy and Sunde (2017) point out that excessively high levels of income inequality erode institutional quality even in democracies, up to the point that democracies cannot implement good institutional framework and governance in the presence of high income inequality in society. Piketty (2014) shows that inequality can lead to a breakdown of good governance and institutional quality in democracies. However, emerging countries can overcome the problem of weak governance of institutions by achieving a democratic consolidation (cf., Faghih and Zali 2018; Guzmán et al. 2019; Lindseth 2017; Aidt and Jensen 2013; Bartlett 1996). In general, the interaction between activities of political institutions and level of inequality shapes institutional governance. In fact, De Tocqueville (1835) argued that high economic inequality can generate a deterioration of the equality of rights. Lipset (1959) claimed that income and equality are basic prerequisites of universal civil rights and economic freedom for the wealth of nations. In this context, Acemoglu et al. (2005) suggest that political institutions and the distribution of resources are critical factors for supporting institutional and economic change of countries. In particular, these factors can explain how institutions affect economic performance and the allocation of resources in society (cf., Olson 1982; Coccia 2005b). Many studies suggest that efficient political institutions and moderate income inequality are conducive to economic growth (Acemoglu et al. 2005). Berg et al. (2018) show that low inequality is associated with faster and more durable economic growth . These scholars also find that more unequal societies tend to redistribute more, but that redistribution does not generate a major effect on economic growth. Cingano (2014) suggests that high inequality has a negative impact on economic growth, because income inequality negatively interacts with human capital and prevent growth. Coccia (2017a) reveals that a high income inequality increases violence in society, creating problems that harm economic growth. The study by Gründler and Scheuermeyer (2018) also reveals negative effects of inequality in poor and middle-income countries. This effect is due to fragile public infrastructure, inefficient institutions, capital market imperfections, and other problematic factors of socioeconomic systems (cf., Coccia 2009). Moreover, processes of redistribution are positive mechanisms for development of poor and middle-income countries but harmful for economic growth in rich countries. Generally, studies suggest a variety of results: inequality limits growth, inequality does not affect development, inequality fosters economic growth , etc. (cf., Cingano 2014; Halter et al. 2014; Lazear and Rosen 1979; Foellmi and Zweimüller 2006). As a matter of fact, high-income inequality could lead to social conflict and exclusion that harm growth of countries (cf., Coccia 2017a; Stiglitz 2013; Wilkinson and Pickett 2010). Some scholars also claim that inequality reduction can decrease investment in education and accumulation of physical capital, and as a consequence, deteriorate long-run economic growth (Checchi et al. 1999; Mookherjee 2006; Okun 2015). Halter et al. (2014) show that high inequality stimulates economic performance and growth in the short run, but high inequality has a negative effect on long-run economic growth (cf., Forbes 2000). Galor and Moav (2004) and Galor and Zeira (1993) state that inequality can affect economic growth by depriving the poor of healthcare and education that are basic factors for human capital development and overall efficiency of institutions and of nations. Finally, Perotti (1996), on the one hand, shows that more equal societies have lower rates of fertility and higher levels of investments in education and research & development that support economic growth. On the other hand, high inequality is associated with economic-political instability and high violence that reduce economic growth of nations (Perotti 1996; cf., Coccia 2017a); furthermore, growth of inequality in land and income ownership has a negative effect on economic development (Alesina and Perotti 1996). Overall, then, a fruitful interaction between income inequality and efficient institutions is basic for supporting economic system and social stability of nations.

2.2 Good Governance and Poverty in Society

Another vital factor in economic system is the level of poverty. Breunig and Majeed (2019) argue that the negative effect of inequality on growth seems to be concentrated in countries with high levels of poverty. Studies suggest that effective and efficient institutions can support a good governance to achieve long-run social and economic objectives, such as low levels of inequality and poverty. Sachs (2005) argues that low income can confine societies to a poverty trap because of a less productive workforce. Bowles et al. (2006) discuss the role of institutions and governance in perpetuating poverty traps. In addition, poverty can increase the growth rates of population, which retard economic growth (Ravallion 2016). In this context, López (2006) and López and Servén (2009) argue that low investments in education and health sector and a low accumulation of physical capital affect both level of poverty and of economic growth. Azariadis and Stachurski (2005) point out that poverty impedes the accumulation of physical capital, human development, and diffusion of new technology that are critical drivers of economic growth (cf., Coccia 2005a, b, c; Coccia 2006a, b, 2008, 2015, 2017c, d, e, 2020b, c; Coccia and Wang 2015). In short, economic literature shows that poverty seems to have a negative effect on investments and growth of countries having a fragile economic and financial structure (Perry 2006).

Hence, how (good) governance of institutions affects poverty alleviation can clarify vital relations underlying social cohesion and economic growth of countries.

This chapter, within this theoretical framework, endeavors to explain the interrelationships among levels of good governance indicators, poverty, and inequality to suggest economic and institutional policies for supporting economic growth of nations.

3 Method

Let start remarking that the measurement of the various dimensions of good governance is a hard topic in social sciences because these characteristics have multidimensionality (cf., Campos 2000; Long 1970; Raiser et al. 2000; Rocco and Thurston 2014). The study here considers a set of indicators to analyze institutional change of economies over time. The concept of governance and its institutional dimensions by World Bank (1992, 1994, 2008, 2013) provide the basis for study design here (Norris 2008; cf., Campos 2000).

3.1 Data and Their Sources

The study is based on a dataset of N = 191 countries with variables in different years (2000, 2004 and 2007), which are combined in a logical model as explained later. Sources of data are: Norris (2008), the OECD (2013), the World Bank (2008), and the Worldwide Governance Indicators (2019).

3.2 Measures

-

Institutional Change and Good Governance Indicators

Institutional change is measured here with the level of good governance across countries (World Bank 1992). In this context, the concept of good governance is different from economic governance , which is defined as: “the structure and functioning of the legal and social institutions that support economic activity and economic transactions by protecting property rights, enforcing contracts, and taking collective action to provide physical and organizational infrastructure. Economic governance is important because markets, and economic activity and transactions more generally, cannot function well in its absence” (Dixit 2009, p. 5ff). Good governance is measured with indicators of formal laws or rules and indicators that measure practical applications or outcomes of these rules (Kaufmann et al. 1999). The indicators applied to measure good governance in this study are listed here, and the description of details is in Appendix A:

-

Kaufmann Voice and Accountability Index in year 2000

-

Kaufmann Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism in year 2000

-

Kaufmann government effectiveness in year 2000

-

Kaufmann government regulatory quality in year 2000

-

Kaufmann Rule of Law in year 2000

-

Kaufmann Control of Corruption in year 2000

Another main indicator of governance is “summary good governance 1996” by Kaufmann and Kraay, having a range [−2; +2] from the lowest to the highest level (cf., Norris 2008). This indicator is associated with indicators of governance just mentioned that are rather stable over the course of time (cf., Kaufmann et al. 1999, 2008, 2010; Norris 2008; Worldwide Governance Indicators 2019; Thomas 2010). This set of indicators is a main base to analyze institutional change of economies over time (cf., Campos 2000).

-

The socioeconomic indicators used here are:

-

Income inequality that is measured with Gini coefficient in the year 2004

-

Poverty that is measured with poverty index value (%) in the year 2004

-

and some analyses also use the following socioeconomic variables:

-

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita based on purchasing power parity (PPP) in the year 2007

-

Annual population growth rate, average 1975–2002 period

-

The Human Development Index (HDI) in the year 2004

3.3 Statistical Analyses, Model Specification, and Estimation Method

Firstly, descriptive statistics (based on arithmetic mean, std. deviation, skewness, and kurtosis coefficients) assess the normality of distributions and if necessary distributions of variables are fixed with a log-transformation. Statistical analyses are also performed categorizing the countries with 3-categories of fragile states in 2006 (cf., Norris 2008; see Appendix B in this chapter here):

-

(a)

Fragile (proxy of emerging countries)

-

(b)

Intermediate (proxy of low- and middle-income countries)

-

(c)

Stable (proxy of advanced countries)

The classification of stable, intermediate, and fragile countries is associated with the type of economy of nations measured with the level of Gross Domestic Product per Capita (GDPPC) in purchasing power parity (World Bank 2009): i.e., countries with High GDPPC ($15,000+) ≈ stable economies, Medium GDPPC ($2000–14,999) ≈ intermediate economies, and Low GDPPC ($2000 or less) ≈ fragile economies. These categories of nations also have a decreasing intensity of democracy from high to low levels of GDPPC (cf., Coccia 2020a). This approach can show the effects of good governance indicators between countries with different levels of socioeconomic development.

Secondly, bivariate and partial correlation verifies relationships (or associations) between variables understudy and measures the degree of association.

Thirdly, the statistical analysis here investigates the relation between independent and dependent variables. In particular, dependent variables (poverty or income inequality, accordingly) are considered as a linear function of a single independent variable or multiple explanatory variables given by good governance indicators and other socioeconomic variables listed in the previous section. Dependent variables have in general a lag of 4–8 years in comparison with explanatory variables to consider long-run dynamic effects of predictors on dependent variables understudy. In general, the relationships here are supported by arguments of Acemoglu et al. (2005), Bowles et al. (2006), Breunig and Majeed (2019), and Olson (1982).

The specification of linear model is:

-

α = constant, β = coefficient of regression, and u = error term.

-

y = dependent variable is income inequality (GINI coefficient 2004) or poverty (human poverty index % 2004), respectively.

-

x = explanatory variable is a measure of the good governance given by: summary good governance 1996 by Kaufmann-Kraay, or Kaufmann government effectiveness 2000, or Kaufmann government regulatory quality 2000, or Kaufmann Rule of Law 2000.

In addition, this study extends the analysis with a multiple regression model to assess how different good governance indicators can affect either income inequality or poverty (as dependent variables). The specification of the dependent variable as a linear function of more explanatory variables xi (i indicates different variables from 1, …, to n) is:

-

α = constant, βi = coefficients of regression, and ε = error term.

-

y = dependent variable is income inequality (GINI coefficient 2004) or poverty (human poverty index % 2004), respectively.

-

xi = explanatory variables: Kaufmann voice and accountability 2000, Kaufmann political stability 2000, Kaufmann government effectiveness 2000, Kaufmann government regulatory quality 2000, Kaufmann rule of law 2000, and Kaufmann corruption 2000.

The statistical analysis also considers the standardized coefficients Beta of estimated relationships to analyze in a comparable framework the different effect of good governance indicators on inequality reduction and poverty alleviation. The relationships (1) and (2) are analyzed considering all sample and subsets of the sample based on fragile, intermediate, and stable economies (as described before) to assess how good governance affects inequality and poverty in countries with different levels of development and socioeconomic stability. Before discussing the empirical results of this study, it is important to remark that the statistical analysis here is exploratory because there is not a specific formal model but a general theoretical framework in which the proposed findings can be checked against to assess consistency. In addition, in this study, institutions are assumed to be exogenous to the socioeconomic indicators of countries under study, thereby justifying the use of the method of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) , as performed by other scholars (cf., Campos 2000). In particular, OLS method is applied for estimating the unknown parameters of relations in linear regression models (1 and 2). Statistical analyses are obtained with the Statistics Software SPSS® version 24.

4 Results

The purpose of the present results is to see whether statistical analyses can explain the research questions stated in Introduction. In particular, the contribution here endeavors to clarify whether and how good governance of institutions affects poverty alleviation and inequality reduction between countries. In addition, results have also to clarify, whenever possible, how good governance indicators affect poverty reduction in emerging or advanced economies. The results can extend the empirical studies in this field of research for explaining the relationships between institutional change, measured with good governance indicators, and levels of poverty and inequality to support best practices of political economy in society.

The statistical analyses show results considering overall sample of countries (N = 191) and three subsets of countries categorized with socioeconomic fragility (i.e., stable, intermediate, and fragile countries) to explain, as far as possible, the relationships between good governance indicators, poverty, and income inequality in society.

Table 1 shows that fragile and intermediate countries have a high average level of income inequality and poverty. This result is associated with negative indicators of good governance. By contrast, stable countries , richer and with a consolidated democracy, have a lower level of poverty and higher levels of good governance, such as Kaufmann voice and accountability, political stability, government effectiveness, government regulatory quality, rule of law, and corruption control (cf., Fig. 1).

Table 2 reveals that a reduction of poverty has a high association with the improvement of government effectiveness, rule of law, and corruption control, synthesized with an improvement of the indicator of “summary good governance” (r = −0.40, p-value = 0.001). Instead, a reduction of income inequality has a high association mainly with the improvement of government effectiveness and rule of law (r = −0.33, p-value = 0.001; r = −0.34, p-value = 0.001 respectively, cf., Table 2).

If correlation analysis is performed considering the categorization of countries in fragile, intermediate, and stable, based on their level of development and stability, results suggest that (Table 3):

-

In fragile countries, the reduction of poverty has a high association with increases of the indexes of voice and accountability, government effectiveness, rule of law, and corruption control, synthetized with an improvement of the indicator of “summary good governance” (r = −0.50, p-value<0.001).

-

In intermediate countries, the reduction of poverty has a high association with the increase of indicator of government effectiveness (r = −0.36, p-value<0.001).

-

In stable countries, the reduction of poverty has a high association with increases of the indexes of political stability, government effectiveness, rule of law , and corruption control, synthetized with an improvement of the indicator of “summary good governance” (r = −0.68, p-value<0.05).

Table 4 shows that high coefficients of partial correlation, controlling income inequality, are between poverty and government effectiveness (pr = −0.50, p-value<0.001), government regulatory quality (pr = −0.51, p-value < 0.001), and summary of good governance (pr = −0.45, p-value<0.001).

If the partial correlation (controlling income inequality) is performed considering the classification of fragile, intermediate, and stable economies, results reveal that the impact of good governance on poverty is higher in stable countries (prstable economies = −0.77, p-value = 0.04), rather than fragile and intermediate countries (Table 5). These findings suggest that other factors, such as higher political stability and democratization, generate reinforcing effects on fruitful interaction between poverty alleviation and good governance indicators.

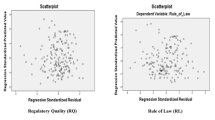

Tables 6 shows regression analysis: the linear model considers income inequality as dependent variable. The reduction of income inequality here, driven by good governance, is high within stable countries (β = −7.80, p-value = 0.05), whereas in fragile and intermediate countries the results are not significant. In stable countries, the coefficient R2 explains about 16% variance in the data (cf., Fig. 2 for estimated regression line using data of N = 118 countries). Although R2 is low in the model for all sample and for stable countries, the Ftest is significant (p-value<0.001 and p-value = 0.03, respectively), then independent variable reliably predicts dependent variable (i.e., income inequality).

Tables 7 considers the poverty as a dependent variable. In this case, the reduction of poverty in stable countries, driven by good governance of institutions, has a coefficient of regression β = −22.15 (p-value = 0.05) that is roughly twofold than magnitude in fragile countries (β = −13.31, p-value = 0.001). Fragile countries have a coefficient R2 that explains more than 25% variance in the data, whereas the coefficient R2 in model of stable countries explains about 46% of variance in the data (cf., Fig. 3 for estimated regression line, using data of N = 79 countries). The linear model with poverty, as a dependent variable, has the F value that is significant (p-value<0.001 for all sample and p-value < 0.05 for stable economies), as a consequence, the explanatory variable of “summary good governance” reliably predicts the level of poverty between countries.

Table 8, using standardized coefficients , shows that good governance indicator has a higher impact on poverty alleviation, rather than inequality reduction. Moreover, results here confirm that the impact of good governance indicator on poverty reduction is higher in stable rather than fragile countries.

Finally, Table 9 shows results of estimated relationships with different good governance indicators on income inequality and poverty. In particular, multiple regression analyses suggest that if Kaufmann government effectiveness increases (or Kaufmann rule of law increases in the model with income inequality), it generates a higher reduction of levels of poverty and income inequality. The coefficient R2 of these models explains more than 24% variance in the data. Studies confirm that even noisy and high-variability data – with low R2 in regression analysis – can have a significant trend, i.e., predictors still provide information about the trend of dependent variable (cf., Figs. 2 and 3). However, different levels of variability in data can also affect the precision of prediction (cf., Draper and Smith 1998; Kennedy 2008). Finally, multiple regression analyses here show that the F test is significant with p-value < 0.001; as a result, explanatory variables provide a reliable prediction of the dependent variable understudy (i.e., income inequality and poverty).

5 Conclusions and Limitations

Breunig and Majeed (2019) argue that higher levels of poverty and inequality negatively affect economic growth . In particular, the negative impact on economic development increases as poverty increases. Ravallion (2002) finds a negative impact of poverty on growth, and Gründler and Scheuermeyer (2018) confirm that inequality within poorer countries has a strong negative impact on economic growth. In short, there are a variety of good reasons because countries have to reduce inequality and poverty in society.

The goal of this chapter was to analyze how a set of good governance indicators can explain levels of income inequalities and poverty that are prerequisites for development of nations. A fundamental question in these research topics is: how does governance of institutions reduce poverty and income inequality between countries?

In general, good governance can decrease income inequality and poverty within and between countries, with reinforcing effects given by higher economic and political stability, democratization, government effectiveness, and rule of law of countries (cf., Coccia 2020a). This general relation is represented in the scheme of Fig. 4. As a matter of fact, Djankov et al. (2002, 2006) and Jalilian et al. (2007) argue that democratization can provide higher levels of political accountability that reduce protection of vested interests. Tarverdi et al. (2019) suggest that the effectiveness of governance increases with education of people and economic development of nations (cf., Farazmand and Pinkowski 2006; Farazmand 2019). Moreover, political and economic stability and the securing of property rights create appropriate socioeconomic environments for institutions to apply interventions of good governance to reduce both income inequality and poverty of nations (Coccia 2016, 2017b).

Empirical results of this study are schematically summarized in Fig. 5 to support institutional and economic policies directed to inequality reduction and poverty alleviation, considering their association and relation with good governance indicators. The central findings here suggest that a good governance of institutions provides a main reduction of poverty, rather than income inequality (cf., Fig. 5).

Effects of the association between improvements of good governance indicators, inequality reduction, and poverty alleviation for supporting political economy of growth

Note: Values are based on bivariate correlation (cf., Table 2). In bolt variables with high association

***Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed)

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Source: Author’s own figure based on statistical analyses performed in 2020

In fact, economic policies , based on good governance to alleviating poverty and income inequality, play a vital role for supporting countries toward sustainable development goals. In general, this chapter offers new insights into the important relationship among good governance, inequality, and poverty for supporting the economic growth of nations. In particular, policy implications of this study are:

-

Income inequality can be reduced mainly with institutional policies directed to improve government effectiveness (r = −0.35, p-value = 0.001) and rule of law (r = −0.34, p-value = 0.001).

-

Poverty can be alleviated mainly with best practices directed to increase government effectiveness (r = −0.50, p-value = 0.001), government regulatory quality (r = −0.45, p-value = 0.001), and rule of law (r = −0.44, p-value = 0.001).

In addition, results in this chapter demonstrate that the fruitful interaction between a good governance and reduction of income inequality and poverty is higher in the presence of stable economies because of a regular economic growth and the emergence and diffusion of new technology in society (Coccia 2005a, 2008, 2010, 2015; Coccia 2017f; Coccia 2018e, f; Coccia 2019c, d; Coccia 2020a, b, c; Coccia and Watts 2020; Faghih 2018). Effective institutions and institutional change targeted to a high level of transparency, participation, and representation can improve good governance both in emerging and in advanced countries (cf., Dixit 2009; Faghih and Zali 2018; Lindseth 2017; Aidt and Jensen 2013; Bartlett 1996). Hence, the improvement of good governance, in the presence of stable economies with consolidated democracies, amplifies the reduction of inequality and poverty supporting long-run economic development of nations (cf., Castelló-Climent 2008; Faghih 2018; Tarverdi et al. 2019). However, Voigt (2013, p. 22ff) points out that econometric findings that explain variation in dependent variables may be a weak basis for modifying institutions at will. In general, the findings here suggest that policymakers for supporting economic growth, ab initio (Latin, from the beginning), have to improve governance effectiveness of institutions and implement sound policies and regulations aimed at reducing poverty and inequality in society. These institutional policies, alleviating poverty and inequality, improve social cohesion and well-being of people, which are vital prerequisites for sustainable development goals of countries (Pullar et al. 2018; Chen and Pan 2019; Coccia 2017a, 2018c, 2019b; Zou et al. 2019). In fact, Rodrik et al. (2004, p. 156) argue that institutions are more relevant for explaining development than both geography and trade, and that institutions ought to be conceptualized as “the cumulative outcome of past policy actions.”

Overall, then, the policy implication of this chapter is that a good governance of institutions based on a high level of governance effectiveness, associated with economic and political stability, has main effects on poverty reduction, supporting consumption growth and social cohesion, which have beneficial effects for economic growth of nations; whereas, the reduction of income inequality with redistribution interventions seems that not reduce poverty and not improve socioeconomic patterns of development of nations.

These conclusions are of course tentative. There is need for much more detailed research into the relations between institutional change, good governance indicators, levels of poverty and inequality in society. To conclude, the challenge for institutional scholars and economists of development is to continue the theoretical and empirical exploration within this terra incognita of the relation between good governance of institutions, income inequality, and poverty of countries to support new findings for appropriate socio-institutional policies directed to sustainable development for widespread social, economic, health, and/or environmental benefits .

References

Acemoglu, D., & Johnson, S. (2005). Unbundling institutions. The Journal of Political Economy, 113(5), 949–995.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2005). Chapter 6: Institutions as the fundamental cause of long-run growth. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., Robinson, J. A., & Yard, P. (2008). Income and democracy. American Economic Review, 98(3), 808–842.

Aidt, T. S., & Jensen, P. S. (2013). Democratization and the size of government: evidence from the long 19th century. Public Choice, 157(3/4). Special Issue: Essays in Honor of Martin Paldam (December), 511–542.

Alesina, A., & Perotti, R. (1996). Income distribution, political instability, and investment. European Economic Review, 40, 1203–1228.

Aoki, M. (2001). Towards a comparative institutional analysis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Azariadis, C., & Stachurski, J. (2005). Poverty traps. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1(1).

Ball, R., & Rausser, G. (1995). Governance structures and the durability of economic reforms: Evidence from inflation stabilizations. World Development, 23(6), 897–912.

Bartlett, D. L. (1996). Democracy, institutional change, and stabilisation policy in Hungary. Europe-Asia Studies, 48(1), 47–83. https://www.jstor.org/stable/152908.

Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2014). Institutional change in economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513507823.

Berg, A., Ostry, J. D., Tsangarides, C. G., & Yakhshilikov, Y. (2018). Redistribution, inequality, and growth: new evidence. Journal of Economic Growth, 23, 259–305.

Bowles, S., Durlauf, S., & Hoff, K. (2006). Poverty traps. Princeton: Russell Sage Foundation. Princeton University Press.

Breunig, R., & Majeed, O. (2019). Inequality, poverty and economic growth. International Economics. ISSN:2110-7017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2019.11.005.

Campbell, J. L. (2004). Institutional change and globalization. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Campos, N. F. (2000). Context is everything: Measuring institutional change in transition economies (Policy Research Working Papers, Series 2269). The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-2269.

Campos, N. F., & Nugent, J. (1999). Development performance and the institutions of governance: Evidence from East Asia and Latin America. World Development, 27, 439–452.

Castelló-Climent, A. (2008). On the distribution of education and democracy. Journal of Development Economics, 87(2), 179–190.

Checchi, D., Ichino, A., & Rustichini, A. (1999). More equal but less mobile? Education financing and intergenerational mobility in Italy and in the US. Journal of Public Economics, 74, 351–393.

Chen, C., & Pan, J. (2019). The effect of the health poverty alleviation project on financial risk protection for rural residents: evidence from Chishui City, China. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-0982-6.

Chong, A., & Calderon, C. (2000). Institutional quality and income distribution. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 48(4), 761–786.

Chong, A., & Gradstein, M. (2007a). Inequality and informality. Journal of Public Economics, 91(1–2), 159–179.

Chong, A., & Gradstein, M. (2007b). Inequality and institutions. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(3), 454–465.

Cingano, F. (2014). Trends in income inequality and its impact on economic growth (OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 163). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5jxrjncwxv6j-en.

Coccia, M. (2005a). Metrics to measure the technology transfer absorption: Analysis of the relationship between institutes and adopters in northern Italy. International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialization, 4(4), 462–486. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTTC.2005.006699.

Coccia, M. (2005b). Countrymetrics: valutazione della performance economica e tecnologica dei paesi e posizionamento dell’Italia. Rivista Internazionale di Scienze Sociali, CXIII(3), 377–412. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41624216.

Coccia, M. (2005c). A taxonomy of public research bodies: A systemic approach. Prometheus, 23(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/0810902042000331322

Coccia, M. (2006a). Classifications of innovations: Survey and future directions (Working Paper Ceris del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Ceris-Cnr Working Paper, vol. 8, n. 2). ISSN (Print): 1591–0709, Available at arXiv Open access e-prints: http://arxiv.org/abs/1705.08955

Coccia, M. (2006b). Analysis and classification of public research institutes. World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 3(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1504/WRSTSD.2006.008759.

Coccia, M. (2008). Spatial mobility of knowledge transfer and absorptive capacity: Analysis and measurement of the impact within the geoeconomic space. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 33(1), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-007-9032-4.

Coccia, M. (2009). Research performance and bureaucracy within public research labs. Scientometrics, 79(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0406-2.

Coccia, M. (2010). Democratization is the driving force for technological and economic change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77(2), 248–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2009.06.007.

Coccia, M. (2015). Technological paradigms and trajectories as determinants of the R&D corporate change in drug discovery industry. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning, 10(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKL.2015.071052.

Coccia, M. (2016, November). The relation between price setting in markets and asymmetries of systems of measurement of goods. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 14(part B), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeca.2016.06.001.

Coccia, M. (2017a, November–December). A Theory of general causes of violent crime: Homicides. Income inequality and deficiencies of the heat hypothesis and of the model of CLASH. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 37, 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.10.005.

Coccia, M. (2017b, June). Asymmetric paths of public debts and of general government deficits across countries within and outside the European monetary unification and economic policy of debt dissolution. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 15, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2010.02.003.

Coccia, M. (2017c). The source and nature of general purpose technologies for supporting next K-waves: Global leadership and the case study of the U.S. Navy’s Mobile User Objective System. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 116(March), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.05.019.

Coccia, M. (2017d). The Fishbone diagram to identify, systematize and analyze the sources of general purpose technologies. Journal of Social and Administrative Sciences, 4(4), 291–303. https://doi.org/10.1453/jsas.v4i4.1518.

Coccia, M. (2017e). Varieties of capitalism’s theory of innovation and a conceptual integration with leadership-oriented executives: The relation between typologies of executive, technological and socioeconomic performances. International Journal of Public Sector Performance Management, 3(2), 148–168. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPSPM.2017.084672.

Coccia, M. (2017f). Sources of disruptive technologies for industrial change. L’industria –rivista di economia e politica industriale, 38(1), 97–120. https://doi.org/10.1430/87140

Coccia, M. (2018a). An introduction to the theories of institutional change. Journal of Economics Library, 5(4), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1453/jel.v5i4.1788. ISSN:2149-2379.

Coccia, M. (2018b). An introduction to the theories of national and regional economic development. Turkish Economic Review, 5(4), 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1453/ter.v5i4.1794.

Coccia, M. (2018c). Economic inequality can generate unhappiness that leads to violent crime in society. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 4(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHD.2018.10011589.

Coccia, M. (2018d). World-system theory: A sociopolitical approach to explain world economic development in a capitalistic economy. Journal of Economics and Political Economy, 5(4), 459–465. https://doi.org/10.1453/jepe.v5i4.1787.

Coccia, M. (2018e). Theorem of not independence of any technological innovation. Journal of Economics Bibliography, 5(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1453/jeb.v5i1.1578.

Coccia, M. (2018f). The origins of the economics of innovation. Journal of Economic and Social Thought, 5(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1453/jest.v5i1.1574

Coccia, M. (2019a). Comparative institutional changes. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1277-1.

Coccia, M. (2019b). Theories of development. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Cham., ISBN:978-3-319-20927-2: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_939-1.

Coccia, M. (2019c). The theory of technological parasitism for the measurement of the evolution of technology and technological forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.12.012.

Coccia, M. (2019d). A Theory of classification and evolution of technologies within a Generalized Darwinism. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 31(5), 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2018.1523385

Coccia, M. (2019e). Why do nations produce science advances and new technology? Technology in society, 59, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.03.007

Coccia, M. (2019f). Revolutions and evolutions. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3708-1

Coccia, M. (2020a). Effects of the institutional change based on democratization on origin and diffusion of technological innovation. In Working Paper CocciaLab n. 44/2020, CNR – National Research Council of Italy, ArXiv.org e-Print archive, Cornell University, USA. Permanent arXiv available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08432

Coccia, M. (2020b). Deep learning technology for improving cancer care in society: New directions in cancer imaging driven by artificial intelligence. Technology in Society, 60(February), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101198.

Coccia, M. (2020c). The evolution of scientific disciplines in applied sciences: Dynamics and empirical properties of experimental physics. Scientometrics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03464-y.

Coccia, M., & Bellitto, M. (2018). Human progress and its socioeconomic effects in society. Journal of Economic and Social Thought, 5(2), 160–178. https://doi.org/10.1453/jest.v5i2.1649.

Coccia, M., & Benati, I. (2018). Rewards in public administration: A proposed classification. Journal of Social and Administrative Sciences, 5(2), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1453/jsas.v5i2.1648.

Coccia, M., & Wang, L. (2015). Path-breaking directions of nanotechnology-based chemotherapy and molecular cancer therapy. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 94, 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.09.007.

Coccia, M., & Watts, J. (2020). A theory of the evolution of technology: Technological parasitism and the implications for innovation management. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 55(2020), 101552, S0923-4748(18)30421-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2019.11.003.

Dacin, M. T., Goodstein, J., & Scott, W. R. (2002). Institutional theory and institutional change: Introduction to the special research forum. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 45–57.

De Tocqueville, A. (1835). Democracy in America. Paris: Gosselin.

Dethier, J. -J. (1999). Governance and economic performance: A survey. Center for Development Research (ZEF), Discussion Paper on Development Policy No 5, April 1999.

Di Maggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). Introduction. In P. J. Di Maggio & W. Powell (Eds.), The new institutionalism and organizational analysis (pp. 1–38). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dixit, A. (2009). Governance institutions and economic activity. American Economic Review, 99(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.1.5.

Djankov, S., La Porta, R., Lopez-de, S. F., & Shleifer, A. (2002). The regulation of entry. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 1–37.

Djankov, S., McLiesh, C., & Ramalho, R. M. (2006). Regulation and growth. Economics Letters, 92, 395–401.

Draper, N. R., & Smith, H. (1998). Applied regression analysis. Wiley-Interscience.

Faghih, N. (2018). An introduction to: Globalization and development – entrepreneurship, innovation, business and policy insights from Asia and Africa. In N. Faghih (Ed.), Globalization and development- entrepreneurship, innovation, business and policy insights from Asia and Africa (pp. 1–10). Cham: Springer.

Faghih N., Zali M. R. (Eds.) 2018. Entrepreneurship ecosystem in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Springer.

Farazmand, A. (2019). Handbook of comparative and development public administration. CRC Press.

Farazmand, A., & Pinkowski, J. (2006). Handbook of globalization, governance, and public administration. CRC Press.

Foellmi, R., & Zweimüller, J. (2006). Income distribution and demand-induced innovations. The Review of Economic Studies, 73, 941–960.

Forbes, K. J. (2000). A reassessment of the relationship between inequality and growth. The American Economic Review, 90(4), 869–887.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2004). From physical to human capital accumulation: Inequality and the process of development. The Review of Economic Studies, 71, 1001–1026.

Galor, O., & Zeira, J. (1993). Income distribution and macroeconomics. The Review of Economic Studies, 60, 35–52.

Greif, A. (2006). Institutions and the path to the modern economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gründler, K., & Scheuermeyer, P. (2018). Growth effects of inequality and redistribution: What are the transmission channels? Journal of Macroeconomics, 55, 293–313.

Guzmán, A., Mehrotra, V., Morck, R., & Trujillo, M.-A. (2019). How institutional development news moves an emerging market. Journal of Business Research, 2019. ISSN:0148-2963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.10.009.

Halter, D., Oechslin, M., & Zweimüller, J. (2014). Inequality and growth: The neglected time dimension. Journal of Economic Growth, 19(1), 81–1044.

International Monetary Fund. (1997). Good governance: The IMF’s role. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Jalilian, H., Kirkpatrick, C., & Parker, D. (2007). The impact of regulation on economic growth in developing countries: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 35, 87–103.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido, L. P. (1999). Governance matters (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No 2196). Washington, DC: World Bank. https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/wbkwbrwps/2196.htm.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2008). Governance matters VII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996–2007. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1148386.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues (September) (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5430). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1682130

Kennedy, P. A. (2008). Guide to econometrics. San Francisco: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kingston, C., & Caballero, G. (2009). Comparing theories of institutional change. Journal of Institutional Economics, 5(2), 151–180.

Kotschy, R., & Sunde, U. (2017). Democracy, inequality, and institutional quality. European Economic Review, 91(C), 209–228.

Kyriazis, N. K., & Karayiannis, A. D. (2011). Democracy, institutional changes and economic development: The case of ancient Athens. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 8(1), 61–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeca.2011.01.003.

Lazear, E. P., & Rosen, S. (1979). Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 841–864.

Lindseth, P. L. (2017). Technology, democracy, and institutional change. In C. Cuijpers, C. Prins, P. Lindseth, & M. Rosina (Eds.), Digital democracy in a globalised world. Edward Elgar.

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69–105.

Long, N. E. (1970). Indicators of change in political institutions. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 388, 35–45. Political Intelligence for America’s Future (Mar., 1970). https://www.jstor.org/stable/1038314.

López, H. (2006). Chapter 6: Does poverty matter for growth. In G. E. Perry, O. S. Arias, J. H. López, W. F. Maloney, & L. Servén (Eds.), Poverty reduction and growth: Virtuous and vicious circles (pp. 103–128). Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

López, H., & Servén, L. (2009). Too poor to grow (Policy Research Working Paper; No. WPS 5012). World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/4204.

Mookherjee, D. (2006). Chapter 15: Poverty persistence and design of antipoverty policies. In A. V. Banerjee, R. Bénabou, & D. Mookherjee (Eds.), Understanding poverty (pp. 231–242). New York: Oxford University Press.

Norris, P. (2008). Democracy time series dataset. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School.

North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

OECD. (2013). Government at a glance 2013. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2013-en.

Okun, A. M. (2015). Equality and efficiency: The big tradeoff (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations: Economic growth, stagnation and social rigidities. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2005). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Perotti, R. (1996). Growth, income distribution, and democracy: What the data say. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(2), 149–187.

Perry, G. (2006). Poverty reduction and growth: Virtuous and vicious circles. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2003). The economic effects of constitutions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pritchett, L., Isham, J., & Kaufmann, D. (1997). Civil liberties, democracy, and the performance of government projects. World Bank Economic Review, 11(2), 219–242.

Pullar, J., Allen, L., Townsend, N., Williams, J., Foster, C., Roberts, N., Rayner, M., Mikkelsen, B., Branca, F., & Wickramasinghe, K. (2018, February 23). The impact of poverty reduction and development interventions on non-communicable diseases and their behavioural risk factors in low and lower-middle income countries: A systematic review. PLoS One, 13(2), e0193378. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193378.

Raiser, M., Di Tommaso, M. L., & Weeks, M. (2000). The measurement and determinants of institutional change. Evidence from transition economies. European Bank for reconstruction and development (Working Paper n. 60).

Ravallion, M. (2001). Growth, inequality and poverty: Looking beyond averages. World Development, 29(11), 1803–1815.

Ravallion, M. (2002). Why don’t we see poverty convergence? The American Economic Review, 102(1), 504–523.

Ravallion, M. (2016). The economics of poverty: History, measurement, and policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rocco, P., & Thurston, C. (2014). From metaphors to measures: Observable indicators of gradual institutional change. Journal of Public Policy, 34(1), 35–62. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X13000305.

Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 9(2), 131–165.

Sachs, J. (2005). The end of poverty: How we can make it happen in our lifetime. London: Penguin Group.

Selznick, P. (1996). Institutionalism “old” and “new”. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 270–277.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2013). The price of inequality. New York: W. W. Norton.

Streeten, P. (1996). Governance. In M. Quibria & J. Dowling (Eds.), Current issues in economic development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tarverdi, Y., Shrabani, S., & Campbell, N. (2019). Governance, democracy and development. Economic Analysis and Policy (Elsevier), 63(C), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2019.06.005.

Thomas, M. A. (2010). What do the worldwide governance indicators measure? The European Journal of Development Research, 22(1), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2009.32.

UNDP. (1995). United nations development program, human development report 1995. New York: Oxford University Press.

UNDP. (2019). United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Reports. http://hdr.undp.org/en/2018-MPI

Voigt, S. (2013). How (Not) to measure institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics, 9(1), 1–26.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2010). The spirit level: Why greater equality makes societies stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

World Bank. (1992). Governance and development. Washington, DC: The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/604951468739447676/Governance-and-development.

World Bank. (1994). Governance: The world bank’s experience. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (1995). World development report: The state in a changing world. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (1996). World development report: From plan to market. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (2008). World development indicators. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators

World Bank. (2009). World development indicators on CD-ROM. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

World Bank. (2013). World development indicators 2013. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://data.worldbank.org. Accessed Oct 2013.

Worldwide Governance Indicators. (2019). https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/. Accessed December

Zou, Q., He, X., Li, Z., et al. (2019). The effects of poverty reduction policy on health services utilization among the rural poor: A quasi-experimental study in central and western rural China. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 186. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1099-7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix A

Description of Good Governance Indicators |

Kaufmann Voice and Accountability index in 2000 captures perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media. Range [−2; +2] from min to max level. |

Kaufmann Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism 2000 measures perceptions of the likelihood of political instability and/or politically motivated violence, including terrorism. Range [−3; +2] from min to max level. |

Kaufmann government effectiveness 2000 captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies. Range [−2; +2] from min to max level. |

Kaufmann government regulatory quality 2000 detects perceptions of the ability of government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector development. Range [−2; +2] from min to max level. |

Kaufmann Rule of Law 2000 captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular quality of contract enforcement, property rights, police, and courts that also reduce the likelihood of crime and violence. Range [−2; +2] from min to max level. |

Kaufmann Control of Corruption 2000 measures perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as “capture” of the state by elites and private interests. Range [−1; +3] from min to max level. |

Description of Socioeconomic Indicators |

Income inequality is measured with Gini coefficient 2004 (World Bank 2013). Gini index measures the extent to which the distribution of income (or, in some cases, consumption expenditure) among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A Lorenz curve plots the cumulative percentages of total income received against the cumulative number of recipients, starting with the poorest individual or household. The Gini index measures the area between the Lorenz curve and a hypothetical line of absolute equality, expressed as a percentage of the maximum area under the line. Thus, a Gini index of 0 represents perfect equality, while an index of 100 implies perfect inequality. |

Poverty with Human poverty index value (%) 2004 (UNDP 2019). This index measures how people experience poverty in multiple and simultaneous ways. It identifies how people are being left behind across three key dimensions: health, education, and standard of living, comprising ten indicators. Data of this index is for N = 97 countries having a range from 2 (low poverty) to 65.5 (high poverty, e.g., many African countries: Ethiopia, Mali, Niger, etc.). |

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita based on purchasing power parity (PPP) 2007. GDP is gross domestic product converted to international dollars using purchasing power parity rates. An international dollar has the same purchasing power over GDP as the US dollar has in the United States. |

Annual population growth rate for year t is the exponential rate of growth of midyear population from year t−1 to t, expressed as a percentage (average 1975–2002). Population is based on the de facto definition of population, which counts all residents regardless of legal status or citizenship. |

The Human Development Index (HDI) 2004 is a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development: having a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable, and having a decent standard of living. The HDI is the geometric mean of normalized indices for each of the three dimensions. |

1.2 Appendix B

Classification of Fragile States in the Year 2006 |

Fragile Countries |

Afghanistan, Algeria, Angola, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Colombia, Congo Dem. Rep., Congo, Rep., Cote d’Ivoire, Ecuador, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Georgia, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Iran, Islamic Rep., Iraq, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyz Republic, Lebanon, Liberia, Macedonia, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Russian Federation, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tajikistan, Thailand, Togo, Turkey, Uganda, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Yemen, Zimbabwe |

Intermediate Countries |

Albania, Argentina, Armenia, Bahrain, Belarus, Belize, Benin, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Comoros, Croatia, Cubism Cyprus, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Fiji, France, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Greece, Grenada, Honduras, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Korea Dem. Rep., Korea Rep., Kuwait, Lao PDR, Lesotho, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Mexico, Moldova, Morocco, Nicaragua, Niger, Panama, Paraguay, Poland, Romania, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, South Africa, Spain, Suriname, Swaziland, Tanzania, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States, Vietnam, Zambia |

Stable Countries |

Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Barbados, Belgium, Bhutan, Botswana, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Cape Verde, Chile, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominica, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Kiribati, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Maldives, Malta, Mauritius, Micronesia, Monaco, Mongolia, Mozambique, Namibia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Oman, Palau, Portugal, Qatar, Samoa, San Marino, Sao Tome and Principe, Seychelles, Singapore, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Sweden, Switzerland, Tonga, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Vanuatu, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Taiwan, Tuvalu |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Coccia, M. (2021). How a Good Governance of Institutions Can Reduce Poverty and Inequality in Society?. In: Faghih, N., Samadi, A.H. (eds) Legal-Economic Institutions, Entrepreneurship, and Management . Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60978-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60978-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-60977-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-60978-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)