Abstract

With the arrival of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), several companies are making significant changes to their systems to achieve compliance. The changes range from modifying privacy policies to redesigning systems which process personal data. Privacy policy is the main medium of information dissemination between the data controller and the users. This work analyzes the privacy policies of large-scaled cloud services which seek to be GDPR compliant. We show that many services that claim compliance today do not have clear and concise privacy policies. We identify several points in the privacy policies which potentially indicate non-compliance; we term these GDPR dark patterns. We identify GDPR dark patterns in ten large-scale cloud services. Based on our analysis, we propose seven best practices for crafting GDPR privacy policies.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Security, privacy, and protection of personal data have become complex and absolutely critical in the Internet era. Large scale cloud infrastructures like Facebook have focused on scalability as one of the primary goals (as of 2019, there are 2.37 billion monthly active users on facebook [12]), leaving security and privacy on the backseat. This is evident from the gravity of personal data breaches reported over the last decade. For instance, the number of significant data breaches at U.S. businesses, government agencies, and other organizations was over 1,300 in 2018, as compared to fewer than 500, ten years ago [4]. The magnitude of impact of such breaches is huge; for example, the Equifax breach [22] compromised the financial information of \(\sim \)145 million consumers. In response to the alarming rise in the number of data breaches, the European Union (EU) adopted a comprehensive privacy regulation called the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [29].

At the core of GDPR is a new set of rules and regulations, aimed at providing the citizens of the EU, more control over their personal data. Any company or organization operational in the EU and dealing with the personal data of EU citizens is legally bound by the laws laid by GDPR. GDPR-compliant services must ensure that personal data is collected legally for a specific purpose, and are obliged to protect it from misuse and exploitation; failure to do so, might result in hefty penalties for the company. As of Jan 2019, 91 reported fines have been imposed under the new GDPR regime [18]. The magnitude of fine imposed varies by the severity of non-compliance. For instance, in Germany, a €20,000 fine was imposed on a company whose failure to hash employee passwords resulted in a security breach. Whereas the French data protection authority, fined Google €50 million for not precisely disclosing how user data is collected across its services to present personalized advertisements. A series of lawsuits and fines have now forced companies to take a more privacy-focused future for their services [10].

While our prior work examined how GDPR affects the design and operation of Internet companies [31] and its impact on storage systems [30], this work focuses on a third dimension : privacy policies (PP). A privacy policy is a statement or a legal document (in privacy law) that states ways in which a party gathers, uses, discloses, and manages a customer or client’s data [14]. The key to achieving transparency, one of the six fundamental data protection principles laid out by GDPR, is a clear and concise PP that informs the users how their data is collected, processed, and controlled. We analyze the privacy policies of ten large-scale cloud services that are operational in the EU and identify themselves as GDPR-compliant; we identify several GDPR dark patterns, points in the PP that could potentially lead to non-compliance with GDPR. Some of the patterns we identify are clear-cut non-compliance (e.g., not providing details about the Data Protection Officer), while others lie in grey areas and are up for interpretation. However, based on the prior history of fines levied on charges of GDPR non-compliance [18], we believe there is a strong chance that all identified dark patterns may lead to charges.

Our analysis reveals that most PP are not clear and concise, sometimes exploiting the vague technical specifications of GDPR to their benefit. For instance, Bloomberg, a software tech company states in its PP that “Bloomberg may also disclose your personal information to unaffiliated third parties if we believe in good faith that such disclosure is necessary [...]”, with no mention of who the third-parties are, and how to object to such disclosure and processing. Furthermore, we identify several dark patterns in the PP that indicate potential non-compliance with GDPR. First, many services exhibit all-or-none behaviors with respect to user controls over data, oftentimes requiring withdrawal from the service to enable deletion of any information. Second, most controllers bundle the purposes for data collection and processing amongst various entities. They collect multiple categories of user data, each on a different platform and state a bunch of purposes for which they, or their Affiliates could use this data. We believe this is in contradiction to GDPRs goals of attaching a purpose to every piece of collected personal information.

Based on our study, we propose seven policy recommendations that a GDPR-compliant company should address in their PP. The proposed policy considerations correspond to data collection, their purpose, the lawfulness of processing them, etc. We accompany each consideration with the GDPR article that necessitates it and where applicable, provide an example of violation of this policy by one of the systems under our study.

Our analysis is not without limitations. First, while we studied a wide category of cloud-services ranging from social media to education, our study is not exhaustive; we do not analyze categories like healthcare, entertainment, or government services. Second, we do not claim to identify all dark patterns in each PP we analyzed. Despite these limitations, our study contributes useful analyses of privacy policies and guidelines for crafting GDPR-compliant privacy policies.

2 GDPR and Privacy Policy

GDPR. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into effect on May 25th 2018 as the legal framework that sets guidelines for the collection and processing of personal information of people in the European Union (EU) [29]. The primary goal of GDPR is to ensure protection of personal data by vesting the control over data in the users themselves. Therefore, the data subject (the person whose personal data is collected) has the power to demand companies to reveal what information they hold about the user, object to processing his data, or request to delete his data held by the company. GDPR puts forth several laws that a data collector and processor must abide by; such entities are classified either as data controller, the entity that collects and uses personal data, or as a data processor, the entity that processes personal data on behalf of a data controller, the regulations may vary for the two entities.

Key Policies of GDPR. The central focus of GDPR is to provide the data subjects extensive control over their personal data collected by the controllers. Companies that wish to stay GDPR-compliant must take careful measures to ensure protection of user data by implementing state-of-the-art techniques like pseudonymization and encryption. They should also provide the data subjects with ways to retrieve, delete, and raise objections to the use of any information pertaining to them. Additionally, the companies should appoint supervisory authorities like the Data Protection Officer (DPO) to oversee the company’s data protection strategies and must notify data breaches within 72 h of first becoming aware of it.

Impact of GDPR. Several services shut down completely, while others blocked access to the users in the European Union(EU) in response to GDPR. For instance, the need for infrastructural changes led to the downfall of several multiplayer games in the EU, including Uber Entertainment’s Super Monday Night Combat and Gravity Interactive’s Ragnarok Online [16], whereas the changes around user consent for data processing resulted in the shut down of advertising companies like Drawbridge [8]. Failure to comply to GDPR can result in hefty fines; up to 4% of the annual global turnover of the company. 91 reported fines have been imposed under the new GDPR regime as of January 2019, with charges as high as €50 million [18].

GDPR and Privacy Policy. A privacy policy is a statement or a legal document (in privacy law) that discloses the ways a party gathers, uses, discloses, and manages a customer or client’s data [14, 28]. It is the primary grounds for transparent data processing requirements set forth by GDPR. GDPR article 12 sets the ground for transparency, one of the six fundamental principles of GDPR. It states that any information or communication to the users must be concise, transparent, intelligible and in an easily accessible form, using clear and plain language. The main objective of this article is to ensure that users are aware of how their data is collected, used, and processed. Therefore, the first step towards GDPR compliance at the controllers is updating the privacy policy, which is the primary information notice board between the controller and the customer.

3 Best Practices for GDPR Compliant Privacy Policies

GDPR has six general data protection principles (transparency; purpose limitation; data minimization; accuracy; storage limitation; and confidentiality) with data protection by design and default at the core. The first step to implementing these data-protection principles is to conceptualize an accurate privacy policy at the data controller.

Privacy policy documents issued by data controllers are oftentimes overlooked by customers either because they are too lengthy and boring, or contain too many technical jargons. For instance, Microsoft’s privacy policy is 56 pages of text [26], Google’s privacy policy spans 27 pages of textual content [19], and Facebook’s data policy document is 7 pages long [11]. A Deloitte survey of 2,000 consumers in the U.S found that 91% of people consent to legal terms and service conditions without reading them [6].

Privacy policies of GDPR-compliant systems must be specific about the sharing and distribution of user data to third- parties, with fine-grained access control rights to users. On the contrary, Apple iCloud’s privacy policy reads as follows [23] : [...] You acknowledge and agree that Apple may, without liability to you, access, use, preserve and/or disclose your Account information and Content to law enforcement authorities, government officials, and/or a third party, as Apple believes is reasonably necessary or appropriate [...] . While this contradicts the goals of GDPR, this information is mentioned on the 11th page of a 20 page long policy document, which most customers would tend to skip.

These observations put together, emphasizes the need for a standardized privacy-policy document for GDPR-compliant systems. We translate GDPR articles into precise questions that a user must find answer to, while reading any privacy policy. An ideal privacy policy for a GDPR-complaint system should at the least, answer all of the following questions prefixed with \(\mathscr {P}\). The GDPR law that corresponds to the question is prefixed with \(\mathscr {G}\).

- ( \(\mathscr {P}\) 1): Processing Entities. :

-

Who collects personal information and who uses the collected information (\(\mathscr {G}\)5(1)B, 6, 21).

The PP of a GDPR-compliant controller must precisely state the sources of data, and with whom the collected data is shared. While many controllers vaguely state that they “may share the data with third-parties”, GDPR requires specifying who the third parties are, and for what purpose they would use this data.

- ( \(\mathscr {P}\) 2): Data Categories. :

-

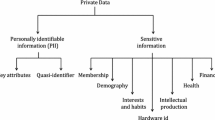

What personally identifiable data is collected (\(\mathscr {G}\)14, 20)

The controller must clearly state the attributes of personal data (name, email, phone number, IP etc) being collected or at the least, categories of these attributes. All the PP we studied fairly addresses this requirement.

- ( \(\mathscr {P}\) 3): Retention. :

-

When will the collected data expire and be deleted (\(\mathscr {G}\)5(1)E, 13, 17)

GDPR requires that the controller attach a retention period or a basis for determining this retention period to every category of personal data collected. Such retention periods or policies must be mentioned straight up in the PP. Apple’s PP for instance, does not mention how long the collected data will reside in their servers [1]. It also provides no detail on whether user data will ever be deleted after its purpose of collection is served.

- ( \(\mathscr {P}\) 4): Purpose. :

-

Why is the data being collected (\(\mathscr {G}\)5(1)B)

Purpose of data collection is one of the main principles of data protection in GDPR. The PP must therefore clearly state the basis for collection of each category of personal data and the legal basis for processing it. The controller should also indicate if any data is obtained from third-parties and the legal basis for processing such data.

- ( \(\mathscr {P}\) 5): User Controls. :

-

How can the user request the following

- (a):

-

All the personal data associated with the user along with its source, purpose, TTL, the list of third-parties to which it has been shared etc (\(\mathscr {G}\)15)

- (b):

-

Raise objection to the use of any attribute of their personal data (\(\mathscr {G}\)21)

- (c):

-

Personal data to be deleted without any undue delay (\(\mathscr {G}\)17)

- (d):

-

Personal data to be transferred to a different controller (\(\mathscr {G}\)20)

Not all PP explicitly state the user’s rights to access and control their personal data. For instance, Uber’s PP has no option to request deletion of user travel history, without having to deactivate the account.

- ( \(\mathscr {P}\) 6): Data Protection. :

-

Does the controller take measures to ensure safety and protection of data

- (a):

-

By implementing state-of-the-art techniques such as encryption or pseudonymization (\(\mathscr {G}\)25, 32)

- (b):

-

By logging all activities pertaining to user data (\(\mathscr {G}\)30)

- (c):

-

By ensuring safety measures when processing outside the EU (\(\mathscr {G}\)3)

GDPR puts the onus of data protection by design and default on the data controller. Additionally, whenever data is processed outside of the EU, the controller should clearly state the data protection guarantees in such case. The PP must also contain the contact details of the data protection officer (DPO) or appropriate channels to request, modify, or delete their information.

- ( \(\mathscr {P}\) 7): Policy Updates. :

-

Does the controller notify users appropriately when changes are made to the privacy policy (\(\mathscr {G}\)14)

The transparency principle of GDPR advocates that the users must be notified and be given the chance to review and accept the new terms, whenever changes are made to the policies. On the contrary, many services simply update the date of modification in the policy document rather than taking measures to reasonably notify the users (for e.g., using email notifications).

4 GDPR Dark Patterns: A Case Study

This section presents the case study of ten large-scale cloud services that are operational in the EU. We analyze various categories of applications and services ranging from social media applications like Whatsapp and Instagram to financial institutions like Metro bank. We study the privacy policies of each of these services and identify GDPR dark patterns that could lead to potential GDPR non-compliance. Table 1 categorizes companies in the descending order of GDPR dark patterns. The discussion below is grouped by the type of commonly observed patterns.

Unclear Data Sharing and Processing Policies. Instagram, a photo and video-sharing social networking service owned by Facebook Inc discloses user information to all its Affiliates (the Facebook group of companies), who can use the information with no specific user consent [24]. The way in which Affiliates use this data is claimed to be “under reasonable confidentiality terms”, which is vague. For instance, it is unclear whether a mobile number that is marked private in the Instagram account, is shared with, and used by Affiliates. This can count towards violation of purpose as the mobile number was collected primarily for account creation and cannot be used for other purposes without explicit consent. Additionally, Instagram says nothing about the user’s right to object to data processing by Affiliates or third-parties. It’s PP says “Our Service Providers will be given access to your information as is reasonably necessary to provide the Service under reasonable confidentiality terms”. Uber on the other hand, may provide collected information to its vendors, consultants, marketing partners, research firms, and other service providers or business partners, but does not specify how the third parties would use this information [40]. On similar grounds, iCloud’s PP vaguely states that information may be shared with third-parties, but does not specify who the third-parties are, and how to opt-out or object to such sharing [23]. Similarly, Bloomberg is vague about third-party sharing and says, “Bloomberg may also disclose your personal information to unaffiliated third parties if we believe in good faith that such disclosure is necessary [...]” [2].

Vague Data Retention Policies. Instagram does not guarantee that user data is completely deleted from its servers when a user requests for deletion of personal information. Data can remain viewable in cached and archived pages of the service. Furthermore Instagram claims to store the user data for a “reasonable” amount of time for “backup”, after account deletion, with no justification of why it is necessary, and whether they will continue to use the backup data for processing. Other companies including Bloomberg and Onavo do not specify a retention period, vaguely specifying that personal information is retained for as long as is necessary for the purpose for which it is collected [2, 27].

Unreasonable Ways of Notifying Updates to Privacy Policy. Changes to PP should be notified to all users in a timely manner and users must be given the chance to review and accept the updated terms. However, edX, Bloomberg, and Snapchat would simply “label the Privacy Policy as “Revised (date)[...]. By accessing the Site after any changes have been made, you accept the modified Privacy Policy and any changes contained therein” [2, 9, 33]. This is un-reasonable as it is easy to miss such notifications, and a better way of notifying users is by sending an email to review the updated policy.

Weak Data Protection Policies. GDPR \(\mathscr {G}\)37 requires the controller to publish contact details of the data protection officer (DPO). The privacy policies of Instagram, Facebook, Bloomberg, and edX have no reference to who the DPO is, or how to contact them. Similarly, while most cloud services assure users that their data processing will abide by the terms in the PP irrespective of the location of processing, services like Onavo take a laidback approach. It simply states that it “may process your information, including personally identifying information, in a jurisdiction with different data protection laws than your jurisdiction”, with nothing said about the privacy guarantees in cases of such processing. Some other services like Uber, state nothing about data protection techniques employed or international transfer policies.

No Fine-Grained Control Over User Data. The edX infrastructure does not track and index user data at every place where the user volunteers information on the site. Therefore, they claim that, “neither edX nor Members will be able to help you locate or manage all such instances.”. Similarly, deleting user information does not apply to “historical activity logs or archives unless and until these logs and data naturally age-off the edX system”. It is unclear if such data continues to be processed after a user has requested to delete his information. Similarly, Uber requires the user to deactivate their account to delete personal information from the system. Moreover, if a user objects to the usage of certain personal information, “Uber may continue to process your information notwithstanding the objection to the extent permitted under GDPR”. It is unclear to what extent, and on what grounds, Uber can ignore the objections raised by users. While most services provide a clear overview the rights user can exercise and the ways of doing so by logging into their service, Onavo simply states, “For assistance with exercising rights, you can contact us at support@onavo.com”. It does not specify what kind of objections can be raised, what part of the personal information can be deleted, etc.

4.1 A Good Privacy Policy

Flybe is a British airlines whose privacy policy was by far the most precise and clear document of all the services we analyzed [15], probably because it’s based in the EU. Nonetheless, the effort put by Flybe into providing all necessary information pertaining to the collection and use of customer’s personal data is an indicator of its commitment to GDPR-compliance. For instance, Flybe clearly categorizes types of user information collected, along with a purpose attached to each category. While most of the services we analyzed claim to simply share information with third-parties as necessary, Flybe enumerates each of its associated third-parties, the specifics of personal data shared with them, the purpose for sharing and a link to the third-parties privacy policy. In cases where it is necessary to process user data outside of EU, Flybe ensures a similar degree of protection as in the EU. We believe that a PP as clear as the one employed by Flybe, enables users to gain a fair understanding of their data and their rights over collected data. The level of transparency and accountability demonstrated by this PP is an indicator of right practice for GDPR-compliance.

4.2 Summary

The major GDPR dark patterns we identify in large-scale cloud services can be summarized as follows.

All or Nothing. Most companies have rolled out new policies and products to comply with GDPR, but those policies don’t go far enough. In particular, the way companies obtain consent for the privacy policies is by asking users to check a box in order to access services. It is a widespread practice for online services, but it forces users into an all-or-nothing choice, a violation of the GDPR’s provision around particularized consent and fine-grained control over data usage. There’s a lawsuit against Google and Facebook for a similar charge [3].

This behavior extends to other types of user rights that GDPR advocates. For instance, GDPR vests in the users the right to object to the use of a part or all of their personal data, or delete it. Most controllers however, take the easy approach and enable these knobs only if they user un-registers for their service. This approach is not in the right spirit of GDPR.

Handwavy About Data Protection. GDPR requires controllers to adopt internal policies and implement measures which meet in particular, the principles of data protection by design and default. However, many cloud services seem to dodge the purpose by stating that in spite of the security measures taken by them (they do not specify what particular measures are taken), the user data may be accessed, disclosed, altered, or destroyed. Whether this is non-compliance is a debatable topic, however, the intent of GDPR \(\mathscr {G}\)24 and \(\mathscr {G}\)25 is to encourage controllers to implement state-of-the-art data protection techniques.

Purpose Bundling. Most controllers bundle the purposes for data collection and processing amongst various entities. They collect multiple categories of user data, each on a different platform and state a bunch of purposes for which they, or their Affiliates could use this data. Although this might not be explicit non-compliance, it kills GDPR’s notion of a purpose attached to every unit of user data collected.

Unreasonable Privacy Policy Change Notifications. Privacy policy being the binding document based on which a user consents to using a service, any changes to the policy must be notified to the user in a timely and appropriate manner. This may include sending an email to all registered users, or in case of a website, placing a notification pop-up without reading and accepting which, the user cannot browse further. However, many services we analyzed have unreasonable update policies, where in they simply update the last modified date in the privacy policy and expect the user to check back frequently.

4.3 User Experiences with Exercising GDPR Rights in the Real World

Privacy policies provide an overview of techniques and strategies employed by the company to be GDPR-compliant, including the rights users can exercise over their data. While no lawsuit can be filed against a company unless there is a proof for violation of any of the GDPR laws claimed in the PP, this section is an account of some users’ attempts to exercise the rights claimed in the PP.

A user of Pokemon Go raised an objection to processing her personal data, and to stop using her personal data for marketing and promotional purposes, both of which are listed under the user’s rights and choices in Pokemon Go’s PP. The response from the controller however, was instructions on how to delete the user account [37]. In another incident, Carl Miller, Research Director at the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media requested an unnamed company to return all personal data they hold about him (which is a basic right GDPR provides to a data subject). However, the company simply responded that they are not the controller for the data he was asking for [39]. Adding on to this, when a user requests for personal information, the company requires him to specify what data he needs [38]. This is not in the right spirit of GDPR because, a user does not know what data a controller might have. This violates the intent of GDPR because the main idea is to give users a better idea of what data is held about them.

These real experiences of common people show that GDPR has a long way to go, to achieve its goal of providing users with knowledge and control over all their personal information collected and processed by various entities.

5 Discussion

The negative responses received by users trying to exercise their GDPR rights, and the shut down of several services in the European Union(EU) in response to GDPR, motivated us to analyze the root cause of this behavior.

One of the notable examples of companies that temporarily shut down services in the EU in response to GDPR and is back in business now, is Instapaper, a read-it-later bookmarking service owned by Pinterest. It is unclear why Instapaper had to take a break; either because it did not have sufficient details on the type of user data its parent Pinterest was receiving from it, or it needed infrastructural support to comply to GDPR’s data subject access request, which allows any EU resident to request all the data collected and stored about them. Interestingly, Instapaper split from Pinterest a month after the GDPR blackout, and soon after, made an independent comeback to the EU. The notable changes in the PP of Instapaper for its relaunch is the change of third-party tools involved in their service, and more detailed instructions on how users can exercise their rights [25].

These trends reveal two critical reasons for non-compliance to GDPR. First, some companies do not have well informed policies for sharing collected data across third-parties, or rely completely on information from third-parties for their data. Second, their infrastructure does not support identifying, locating, and packaging user data in response to user queries. While the former can be resolved by ensuring careful data sharing policies, the latter requires significant reworking of backend infrastructure. Primarily, the need for infrastructural changes led to the downfall of several multiplayer games in the EU, including Uber Entertainment’s Super Monday Night Combat, Gravity Interactive’s Ragnarok Online and Dragon Saga and Valve’s entire gaming community [16]. In this context, we identify 4 primary infrastructural changes that a backend storage system must support in order to be GDPR-complaint [30] and suggest possible solutions in each case.

5.1 Timely Deletion

Under GDPR, no personal data can be retained for an indefinite period of time. Therefore, the storage system should support mechanisms to associate time-to-live (TTL) counters for personal data, and then automatically erase them from all internal subsystems in a timely manner. GDPR allows TTL to be either a static time or a policy criterion that can be objectively evaluated.

Challenges. With all personal data possessing an expiry timestamp, we need data structures to efficiently find and delete (possibly large amounts of) data in a timely manner. However, GDPR is vague in its interpretation of deletions: it neither advocates a specific timeline for completing the deletions nor mandates any specific techniques.

Possible Solutions. Sorting data by secondary index is a well-known technique in databases. One way to efficiently allow deletion is to maintain a secondary index on TTL (or expiration time of data) like timeseries databases [13]. Addressing the second challenge requires a common ground among data controllers to set an acceptable time limit for data deletion. This is an important clause of an ideal Privacy Policy document. Thus, it remains to be seen if efforts like Google cloud’s guarantee [5] to not retain customer data after 180 days of delete requests be considered compliant behavior.

5.2 Indexing via Metadata

Several articles of GDPR require efficient access to groups of data based on certain attributes. For example, collating all the files of a particular user to be ported to a new controller.

Challenges. Storage systems must support interfaces that efficiently allow accessing data grouped by a certain attribute. While traditional databases natively offer this ability via secondary indices, not all storage systems have efficient or configurable support for this capability. For instance, inserting data into a MySQL database with multiple indexes is almost 4\(\times \) slower when compared insertion in a table with no indexes [35].

Possible Solutions. Several research in the past have explored building efficient multi-index stores. The common technique used in multi-index stores is to utilize redundancy to partition each copy of the data by a different key [32, 34]. Although this approach takes a hit on the recovery time, it results in better common-case performance when compared to naive systems supporting multiple secondary indexes.

5.3 Monitoring and Logging

GDPR allows the data subject to query the usage pattern of their data. Therefore, the storage system needs an audit trail of both its internal actions and external interactions. Thus, in a strict sense, all operations whether in the data path (say, read or write) or control path (say, changes to metadata or access control) needs to be logged.

Challenges. Enabling fine grained logging results in significant performance overheads (for instance, Redis incurs 20\(\times \) overhead [30]), because every data and control path operation should be synchronously persisted.

Possible Solutions. One way to tackle this problem is to use fast non-volatile memory devices like 3D Xpoint to store logs. Efficient auditing may also be achieved through the use of eidetic systems. For example, Arnold [7] is able to remember past state with only 8% overhead. Finally, the amount of data logged may be optimized by tracking at the application level instead of the fine-grained low level audit trails. While this might be sufficient to satisfy most user queries, it does not guarantee strict compliance.

5.4 Access Control and Encryption

As GDPR aims to limit access to personal data to only permitted entities for established purposes and for a predefined duration of time, the storage system must support fine-grained and dynamic access control.

Challenges. Every piece of user data can have its own access control list (ACL). For instance, the user can provide Facebook access to his list of liked pages to be used by the recommendation engine, while deny access to his contact number to any application inside of Facebook. Additionally, users can modify ACLs at any point in time and GDPR is not specific if all previously accessed data for which access is revoked, must be immediately marked for deletion. Therefore, applications must validate access rights every time they access user data, because ACL might have changed between two accesses.

Possible Solutions. One way of providing fine grained access control is to deploy a trusted server that is queried for access rights before granting right to data [17]. The main downside is that, it allows easy security breaches by simply compromising this server. A more effective way is to break down user data and encrypt each attribute using a different public key. Applications that need to access a set of attributes of user data should posses the right private keys. This approach is termed Key-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption (KP-ABE) [20]. Whenever the ACL for a user data changes, the attributes pertaining to this data must be re-encrypted. Assuming that changes in access controls are infrequent, the cost of re-encryption will be minimal. While this approach addresses the issue of fine grained access control, more thought needs to go into reducing the overhead of data encryption and decryption during processing. One approach to reduce the cost of data decryption during processing is to explore techniques that allow processing queries directly over encrypted data, avoiding the need for decryption in the common case [21, 36].

6 Conclusion

We analyze the privacy policies of ten large-scale cloud services, identifying dark patterns that could potentially result in GDPR non-compliance. While our study shows that many PP are far from clear, we also provide real world examples to show that exercising user rights claimed in PP is not an easy task. Additionally, we propose seven recommendations that a PP should address, to be close to GDPR-compliance.

With the growing relevance of privacy regulations around the world, we expect this paper to trigger interesting conversations around the need for clear and concrete GDPR-compliant privacy policies. We are keen to extend our effort to engage the storage community in addressing the research challenges in alleviating the identified GDPR dark patterns, by building better infrastructural support where necessary.

References

Apple privacy policy. www.apple.com/legal/privacy/en-ww/. Accessed May 2019

Bloomberg privacy policy. www.bloomberg.com/notices/privacy/. Accessed May 2019

Brandom, R.: Facebook and Google hit with \$8.8 billion in lawsuits on day one of GDPR. The Verge, 25 May 2018

Data breaches. www.marketwatch.com/story/how-the-number-of-data-breaches-is-soaring-in-one-chart-2018-02-26. Accessed May 2019

Data Deletion on Google Cloud Platform. https://cloud.google.com/security/deletion/. Accessed May 2019

Deloitte privacy survey. www.businessinsider.com/deloitte-study-91-percent-agree-terms-of-service-without-reading-2017-11. Accessed May 2019

Devecsery, D., Chow, M., Dou, X., Flinn, J., Chen, P.M.: Eidetic systems. In: USENIX OSDI (2014)

Drawbridge shutdown. https://adexchanger.com/mobile/drawbridge-exits-media-business-europe-gdpr-storms-castle/. Accessed May 2019

edX privacy policy. www.edx.org/edx-privacy-policy. Accessed May 2019

Facebook privacy future. www.facebook.com/notes/mark-zuckerberg/a-privacy-focused-vision-for-social-networking/10156700570096634/. Accessed May 2019

Facebook data privacy policy. www.facebook.com/policy.php. Accessed May 2019

Facebook users. https://s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_financials/2019/Q1/Q1-2019-Earnings-Presentation.pdf. Accessed May 2019

Faloutsos, C., Ranganathan, M., Manolopoulos, Y.: Fast subsequence matching in time-series databases, vol. 23. ACM (1994)

Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M.: Consumer trust, perceived security and privacy policy: three basic elements of loyalty to a web site. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 106(5), 601–620 (2006)

Flybe privacy policy. https://www.flybe.com/privacy-policy. Accessed May 2019

Gaming shutdown. https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Layton%20Testimony1.pdf. Accessed May 2019

Gavriloaie, R., Nejdl, W., Olmedilla, D., Seamons, K.E., Winslett, M.: No registration needed: how to use declarative policies and negotiation to access sensitive resources on the semantic web. In: Bussler, C.J., Davies, J., Fensel, D., Studer, R. (eds.) ESWS 2004. LNCS, vol. 3053, pp. 342–356. Springer, Heidelberg (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-25956-5_24

GDPR fines. https://www.dlapiper.com/en/uk/insights/publications/2019/01/gdpr-data-breach-survey/. Accessed May 2019

Google privacy policy. www.gstatic.com/policies/privacy/pdf/20190122/f3294e95/google_privacy_policy_en.pdf. Accessed May 2019

Goyal, V., Pandey, O., Sahai, A., Waters, B.: Attribute-based encryption for fine-grained access control of encrypted data. In: Proceedings of the 13th ACM conference on Computer and communications security, pp. 89–98. ACM (2006)

Hacigümüş, H., Iyer, B., Li, C., Mehrotra, S.: Executing SQL over encrypted data in the database-service-provider model. In: Proceedings of the 2002 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, pp. 216–227. ACM (2002)

Haselton, T.: Credit reporting firm Equifax says data breach could potentially affect 143 million US consumers. CNBC, 7 September 2017

iCloud privacy policy. https://www.apple.com/uk/legal/internet-services/icloud/en/terms.html. Accessed May 2019

Instagram privacy policy. https://help.instagram.com/402411646841720. Accessed May 2019

Instapaper privacy policy. https://github.com/Instapaper/privacy/commit/05db72422c65bb57b77351ee0a91916a8f266964. Accessed May 2019

Microsoft privacy policy. https://privacy.microsoft.com/en-us/privacystatement?PrintView=true. Accessed May 2019

Onavo privacy policy. https://www.onavo.com/privacy_policy. Accessed May 2019

Privacy policy. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Privacy_policy. Accessed May 2019

General Data Protection Regulation: Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46. Official Journal of the European Union, vol. 59, no. 1–88 (2016)

Shah, A., Banakar, V., Shastri, S., Wasserman, M., Chidambaram, V.: Analyzing the impact of GDPR on storage systems. In: 11th USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Storage and File Systems (HotStorage 2019), Renton, WA. USENIX Association (2019). http://usenix.org/conference/hotstorage19/presentation/banakar

Shastri, S., Wasserman, M., Chidambaram, V.: The Seven Sins of personal-data processing systems under GDPR. In: USENIX HotCloud (2019)

Sivathanu, M., et al.: INSTalytics: cluster filesystem co-design for big-data analytics. In: 17th USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies (FAST 2019), pp. 235–248 (2019)

Snapchat privacy policy. https://www.snap.com/en-US/privacy/privacy-policy/. Accessed May 2019

Tai, A., Wei, M., Freedman, M.J., Abraham, I., Malkhi, D.: Replex: a scalable, highly available multi-index data store. In: 2016 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 2016), pp. 337–350 (2016)

The Performance Impact of Adding MySQL Indexes. https://logicalread.com/impact-of-adding-mysql-indexes-mc12/#.XOMPrKZ7lPM. Accessed May 2019

Tu, S., Kaashoek, M.F., Madden, S., Zeldovich, N.: Processing analytical queries over encrypted data. Proc. VLDB Endowment 6, 289–300 (2013)

Twitter - Pokemon GO information. https://twitter.com/swipp_it/status/1131410732292169728. Accessed May 2019

Twitter - requesting user information requires specification. https://twitter.com/carljackmiller/status/1117379517394432002. Accessed May 2019

Twitter - user information. https://twitter.com/carljackmiller/status/1127525870770577409. Accessed May 2019

Uber privacy policy. https://privacy.uber.com/policy/. Accessed May 2019

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Mohan, J., Wasserman, M., Chidambaram, V. (2019). Analyzing GDPR Compliance Through the Lens of Privacy Policy. In: Gadepally, V., et al. Heterogeneous Data Management, Polystores, and Analytics for Healthcare. DMAH Poly 2019 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11721. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33752-0_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33752-0_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-33751-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-33752-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)