Abstract

Student workload is an issue that has implications for undergraduate student learning, achievement and well-being. Time pressure, although not the only factor that influences students’ workload or their perception of it, is very pivotal to students’ workload. This may vary from one country to the other and maybe affected by cultural differences. The current study investigated the impact of nationality and time pressure on well-being outcomes as well as perceptions of academic stress and academic work efficiency. The study was cross-cultural and cross-sectional in nature and comprised 360 university undergraduates from three distinct cultural backgrounds: White British, Ethnic Minorities (in the United Kingdom) and Nigerian. The findings suggest that time pressure directly or indirectly (i.e. in tandem with nationality) predicted negative outcomes, work efficiency and academic stress. This implies that nationality/ethnicity also plays a role in the process.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

1.1 Conceptualizing Student Workload

Human mental workload is probably the most researched concept “in human factors research and practice” [1]. It describes the demands mental tasks place on the information processing skills of the brain in a way that is analogous to how physical demands tax the muscles [1]. It, thus, can be deduced that workload in occupational settings hinges heavily on occupational demands [2]. Fan and Smith [3] assert that “job demands refer to workload”. In student settings, however, workload has been defined as “the time needed for contact and independent study, the quantity and level of difficulty of the work, and the type and timing of assessments, the institutional factors such as teaching and resources, and student characteristics such as ability, motivation and effort” [4]. It can be deduced from this definition that time plays a crucial role in student workload. However, it has been argued that time is not the only factor that contributes to workload [4,5,6,7]. As this definition shows, there are other factors that affect workload. Some of these factors as listed by Bowyer [4] include “institutional factors” like the quality and method of teaching, how much support staff are willing to give students within and beyond the classroom etc; difficulty of the subject matter; how individual modules are planned in terms of assessment submission dates; type of assessment; allocation of time between “contact time” and personal study; and the student’s ability, motivation and effort. High workload has been associated with the tendency for students to adopt surface learning strategies as opposed to deep learning approaches [8, 9], and an increased likelihood to cheat and plagiarize [8] as well as the intention to quit university [4]. Student workload is divided into objective and subjective workload [4]. While objective workload is based on the estimated amount of time it takes the average student to complete all the tasks – i.e. class attendance, independent and/or group study, laboratory work, assessments etc. - related to a particular academic module or course [4, 6,7,8,9, 11], subjective workload is based on the students’ perception of their workload which may or may not be related to time [4, 6, 7, 10]. Kyndt, Berghmans, Dochy and Bulckens [7] further classified subjective workload into “quantitative perceived work-load” and “qualitative perceived workload” where quantitative perceived workload deals with aspects of workload and qualitative perceived workload had to do with the “feelings of stress, pressure or frustration” associated with high workload. Objective workload is based on course designers’ estimate of how long it should take the average student do all that is required to achieve success in a module or course. It is purely based on estimates and calculations made by people other than the students themselves. A major weakness of objective workload is that it assumes the students’ ability and the expected use of their time rather than the individual student’s perception of their workload [6, 12]. Thus, the subjective approach is suggested. Although the subjective accounts of workload have been criticized as being a difficult means of assessing student workload [10], it is preferred as it considers the contextual factors impacting student workload.

1.2 Time Pressure and Workload

Although it has been argued that time is not the only issue that influences student workload (e.g. [4, 6]), it nevertheless plays a pivotal role. Smith [13] reported a significant correlation between time pressure and workload. Time pressure, as it relates to workload, may not solely stem from the amount of time required for studying and academic activities. It often arises because the students have other commitments that compete for their time. As Chambers [10] explains: “when students suffer interruptions to their studies as a result of illness, family difficulties or whatever, their anxiety is often expressed as a feeling of overburden.”

Other factors could include part-time work, extracurricular activities and socializing with friends [6]. While it may seem quite intuitive for students to desist from or reduce participation in these activities, it may not be a realistic solution as they have their own advantages and improve their student experience. For instance, part-time work could help indigent students cater for their financial needs. Likewise, there is evidence revealing that extracurricular activities could help form strong social bonds which are important to students’ overall well-being [6]. Furthermore, socializing with friends from the same class in addition to yielding social support has also been found to help students with difficult problems revealed during individual study [6]. Conversely, having limited time to spend with friends and family as a result of heavy workload has led to stress for some students [14, 15]. Therefore, even though time is not the only component of workload, it is very pivotal to its perception. Particularly, time pressure, having to do with students “having too many things to do at once”, which may or may not be related to their university work is very central to their perception of their workload. Thus, making time pressure a very important issue to study.

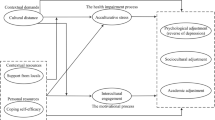

1.3 Workload, Time Pressure and Well-Being

Firstly, it is pertinent to attempt an explanation of the well-being concept. Ryan and Deci [16] define well-being as “optimal psychological function and experience”. The implication of this is that well-being is not just about living, feeling or being well, it also has to do with living to one’s full potential. Well-being is divided into positive (e.g. happiness, positive affect etc.) or negative aspects (e.g. stress, depression and anxiety). There is a tendency for the well-being discourse or research about it to focus on either aspect – and thus infer well-being from the presence or absence of that aspect. This viewpoint assumes that positive and negative well-being are diametrically opposed. However, previous research (e.g. [16,17,18]) has revealed that this is not necessarily the case. Therefore, it has been suggested that well-being should be looked at holistically, integrating both the positive and negative aspects. Thus, helping to paint a, hopefully, more realistic picture of an individual’s well-being. To measure well-being, this way, a model that integrates both aspects of well-being is required. One such model is the Demand-Resources Individual Effects (DRIVE) model [19]. It places emphasis on the individual [19] and has been used in occupational as well as educational settings (e.g. [20,21,22]). In addition to its being able to measure well-being holistically, the DRIVE model was not developed as “a predictive model but rather a theoretical framework into which any relevant variables can be introduced” [19]. Thus, making it flexible and adaptable to whatever well-being or related variables are to be investigated [23]. As a result of this flexibility, the DRIVE model has been used to investigate the relationship between fatigue and heavy workload in occupational samples where high workload was found to be linked with fatigue and impaired performance [3, 24]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the model has only been used by one study [13] to investigate the relationship between time pressure and/or workload and well-being in student settings. This section explores the nexus, from literature, between time pressure and/or workload on the one hand and well-being on the other. Most of the reviewed literature, except Smith (submitted), considered the relationship between either time pressure and well-being or student workload and well-being. Additionally, there was a tendency for the literature to use the typical approach of considering only one aspect of well-being. As mentioned earlier, Smith [13] found a significant correlation between time pressure and workload. This finding shows that, although both concepts are strongly related, they are not the same. It seems to align with the previous assertion that time pressure is a crucial aspect of student workload. This difference was further proven by the fact that although workload significantly predicted work efficiency, course stress, and both negative and positive well-being outcomes, time pressure only significantly predicted only course stress and negative well-being. High workload was consistently related to increased negative well-being [13,14,15, 25]. It is also interesting to note that some studies [13, 14] actually showed positive relationships between high workload and positive well-being outcomes. This finding could be surprising as high workload might be thought to be negative as it places the students under high pressure and could lead to “difficulty, stress and anxiety and the intention to quit” [4]. This seems to indicate that high workload, in itself, may not be bad or be the problem but it could have some negative implications. One key implication may be the pressure it places on the individual’s time resources. For instance, Bergin and Pakenham [14] found that although the respondents in this study were able to cope with their workload, the high workload meant that they were isolated socially which ultimately led to reduced life satisfaction. Furthermore, Smith [13] found time pressure to significantly predict negative well-being outcomes and course stress. Likewise, time pressure as a component of job demands was found to significantly predict anxiety and depression [25] This somewhat agrees with the findings of Kyndt, Berghmans, Dochy and Bulckens [7] who reported that some students’ perception of their workload was shaped by time pressure. Although the literature linking student workload and/or time pressure on the one hand and well-being on the other seem to be reporting similar findings – a tendency for an increase in negative well-being and decrease in positive well-being – there seem to be some weaknesses in how the outcomes where characterized. One key weakness was that much of the literature (e.g. [14, 25]) limited the negative outcomes to anxiety and depression which were considered singly as opposed to Smith’s approach which was a single score for the negative outcomes (comprising the sum for scores from stress, depression and anxiety). A similar trend was observed for positive well-being outcomes. For instance, Bergin and Pakenham [14] only used life satisfaction in comparison to Smith’s aggregation of life satisfaction, positive affect into an overall positive outcome score. One study [25], used a student-adapted version of the Decision-Control Support (DCS) framework [26, 27]. The DCS works on the assumption that situations of high demand, low control and low social support will lead to negative consequences in terms of psychological strain. Although this study [25] findings agree with those from other studies which applied other theoretical frameworks, the DCS model has been criticized for not taking the actual individual into account [19, 28]. It works on the assumption that once the environmental characteristics are present the result is inevitable, neglecting the role that individual coping mechanisms play. This is as opposed to frameworks like the DRIVE model which attempt to account for the roles that individual differences play in the well-being process. The current study will be similar to Smith [13] in many respects. However, one key difference is that the role of nationality will be investigated in addition to those of the predictors.

1.4 Nationality, Workload, Time Pressure and Well-Being

To add another layer to the investigation of the role of workload and/or time pressure in the prediction of well-being outcomes, the role of nationality in this process will be examined. It appears none of the studies placed a very high emphasis on the role of nationality in the process. As could be expected, international students may experience study difficulties due to differences in the educational systems in their home countries and their study country [29]. However, high workload seems to be common to both international and home students [30, 31]. Although, these findings seem to contradict those of Cotton, Dollard and de Jonge [27] who found country of birth to be significantly correlated to “study load”. In this study [27], study load appeared to refer to whether the student was in full-time or part-time study. Again, Sheldon and Krieger [32] controlling for ethnicity among other demographic factors revealed a general tendency for reduced positive well-being and increased negative well-being in all participants irrespective of their ethnic background and demographic characteristics. Putting all these together, it thus could be inferred that cultural differences, in terms of nationality or ethnicity do not intervene in the prediction of well-being outcomes by workload or time pressure.

1.5 Study Aim

The key aim of this study is to investigate the roles, if any, of cultural differences (nationality/ethnicity) singly, and in tandem with time pressure in the prediction of well-being outcomes as well as academic stress and work efficiency.

2 Methodology

2.1 Sample Description

The sample comprised 360 university undergraduates aged 17–42 (mean age = 20.94) from the three distinct ethnic/cultural backgrounds: White British (schooling in the United Kingdom, UK), 144; Ethnic Minorities (schooling in the UK), 103 and Nigerian (schooling in Nigeria), 113. Females made up 59.4% of the sample.

2.2 Instrument

The Qualtrics platform. Each participant gave informed consent before going on to complete the questionnaire and each phase of the data collection was approved by the Cardiff University School of Psychology Ethics Committee. The Questionnaire was delivered in the English Language. The data collected using the Student Well-being Process Questionnaire (Student WPQ) [33]. The instrument was developed to measure well-being predictors and outcomes peculiar the university undergraduate population outcomes [33] and was based on the DRIVE model [19]. The questionnaire consisted of questions encompassing various facets of well-being predictors and outcomes specific to university undergraduates. The single items were statements with explanatory statements in parentheses [34]. Some of the questions were drawn from the single-item adaptations following factor analyses of the Inventory of College Students’ Recent Life Experiences (ICSRLE) [35] by Bdenhorn, Miyazki, Ng and Zalaquett [36]. An example of a single item adapted was “Time Pressure (e.g. too many things to do at once, interruptions of your school work, a lot of responsibilities)”. Respondents were to give ratings of 1–10 (1 = Low, 10 = High) of how the statements represented their personal experiences. In like manner, three single-items on social support were drawn from the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) factors short version [37]. A sample question is presented thus: “There is a person in my life who would provide tangible support for me when I need it (e.g. money for tuition or books, use of their car, furniture for new apartment)”. The scoring was as described for the ICSRLE, with respondents giving rating for 1–10 (1 = Low, 10 = High). Other questions covered well-being predictors covered positive personality, negative coping and conscientiousness. Most questions followed the visual scale (i.e. 1–10) which are preferred to the Likert-scale as the former has been found to be more suitable for single-item questions representing whole constructs [34]. The scores for positive personality were derived from the sum of individual scores on single-item questions for optimism, self-esteem and self-efficacy. Similarly, negative coping was an aggregate of scores on single items on avoidance, self-blame and wishful thinking which have been identified as negative coping styles. These predictors i.e. Student stressors (ICSRLE factors), social support (ISEL factors), conscientiousness, positive personality and negative coping are jointly referred to as the ‘established predictors’ of student well-being. They are so called because they typically predict negative and positive well-being outcomes when the student WPQ is used (e.g. [21, 22, 33]). The full questionnaire is shown in the Appendix.

2.3 Statistical Analyses

The goal of the research described here was to investigate the role played by time pressure and nationality in predicting positive well-being outcomes, negative well-being outcomes, course stress and work efficiency. While negative and positive outcomes were composites derived from summing up scores from individual outcomes, course stress and work efficiency scores were derived from the respective single item for either construct. The first step in the analyses was to split the predictor variable scores into “high” and “low” percentile groups at the median. Nationality was a nominal variable split into White British, Ethnic Minority and Nigerian based on the nationality/ethnicity of the study participants. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tests were then conducted to ascertain the predictive influence of time pressure and nationality on the outcomes. Time pressure and nationality were inputted as the predictors (fixed factors) while controlling for negative coping, positive personality, conscientiousness, student social support (ISEL), (academic) developmental challenges, social annoyances, academic dissatisfaction, romantic problems, social mistreatment and friendship problems (as covariates). The covariates were also split into high and low groups at the median. Also, worth mentioning is that (academic) developmental challenges, academic dis-satisfaction, romantic problems, social mistreatment were factors from the ICSRLE from which time pressure emerged. The main effects of each of the predictors (time pressure and nationality) and co-variates in the prediction of the outcomes were investigated. Likewise, the two-way interactions between nationality and time pressure, as well as with each of the co-variates. For instance, the predictive effect of academic dissatisfaction in predicting the outcomes was investigated singly, as well as the predictive effects of academic dissatisfaction in tandem with nationality. These analyses were done with SPSS 25.

3 Results

3.1 Negative Outcomes

ANOVAs were carried out as described in the previous section for the prediction of negative outcomes. The negative outcome scores comprised scores from individual single-items on depression, anxiety and life stress. Some of the established effects were observed: negative coping and positive personality both significantly predicted negative outcomes (p < .001). Table 1 presents all the results of the significant effects and those of nationality and time pressure.

Nationality was found to significantly predict negative outcomes (p < .05). Figure 1 shows the mean values of negative outcomes for the three groups.

Although time pressure, on its own, did not significantly predict negative outcomes, it did so when combined with nationality. Table 2 presents the means of negative outcomes as predicted by the combination of Nationality and time pressure.

3.2 Positive Outcomes

Positive outcomes score was derived by summing up the responses to single-item questions on happiness, life satisfaction and positive affect. The findings show that neither nationality nor time pressure significantly predicted positive outcomes, although nationality combined with social annoyance yielded significant predictions. Furthermore, positive personality, student social support and conscientiousness were all significant predictors of positive outcomes. These findings are presented in Table 3.

3.3 Course Stress

Course stress was measured by a single item which asked the respondents to give a rating of 1–10 (1 = Low, 10 = High) of how stressful they found their course to be. Time pressure significantly predicted course stress (p < .001), as did the combination of nationality and positive personality (p < .05). There were no other significant predictions observed. The findings are presented in Table 4. Figure 2 also presents the means of high and low time in the prediction of course stress.

3.4 Work Efficiency

Work efficiency was a single-item subjective measure of how efficiently the student carried out their university work. Developmental challenges, conscientiousness, student social support all significantly predicted work efficiency. Also, when nationality combined with time pressure, they significantly predicted work efficiency. Table 5 presents the results in detail. Table 6 presents the means for work efficiency for high and low time pressure according to nationality.

4 Discussion

This study investigated the role of cultural differences (nationality, ethnicity) and time pressure in the prediction of well-being outcomes as well as work efficiency and course stress while controlling for the established factors (negative coping, positive personality, social support (ISEL factors), conscientiousness) and all the other ICSRLE student stressors except time pressure. The first thing worth noting was that some of the established effects for the prediction of negative and positive well-being outcomes were retained. This agrees with previous research with the student WPQ/DRIVE [21, 33]. However, nationality on its own was found to significantly predict negative outcomes, with the Nigerian students showing much lower scores than the White British and Ethnic Minority Students (Fig. 1). This contradicts the findings of Omosehin and Smith [38] which found nationality, on its own, to not predict either positive or negative outcomes in workers. This could be indicating that the well-being process in students differs quite markedly from that of workers. Another plausible explanation is that, as the mean negative outcomes score for Nigerian students was much lower than those of the others (Fig. 1), it could be that nationality per se does not necessarily predict negative outcomes but, rather, the extent to which it is experienced. In that wise, it could be argued that the Nigerian students experienced negative outcomes to a much lesser degree. Yet another possibility is that as the British sample (White British and Ethnic Minority samples) experienced higher negative outcomes than the Nigerian sample, it could be that some geographical or environmental factors affected their perception of experiencing negative well-being. Nigerian students probably perceived some issues as being normal aspects of everyday living or student life and did not perceive them as negative well-being issues. This may also have to do with resilience in terms of seeing an issue as a challenge to be overcome or a problem to be solved rather than a negative situation. Resilience is an individual’s ability to “thrive in the face of adversity” [39] and this seems to aptly describe the Nigerian students’ disposition to perceived negative circumstances. Future studies should include larger samples and include variables like resilience in order to further investigate this. Qualitative studies should also be encouraged in order to tease out possible contextual factors that could account for this disparity in perceptions. Time pressure is not the same thing as workload. Nevertheless, it plays a pivotal role as time is crucial to the perception of workload. This was further buttressed by Smith [13] who found a significant correlation between time pressure and workload. Therefore, it follows that perceptions of time pressure will greatly influence workload. The current study found time pressure to significantly predict course stress, which replicates Smith’s [14] findings. This finding seems logical as students who feel they do not have enough time to give to their academic activities are likely to view their course as stressful. The feelings that the course is stressful could increase the likelihood of plagiarism. Devlin and Gray [8] report that time pressure leads to plagiarism. This may be a result of their inability to manage their time effectively to juggle academic and non-academic aspects of their lives. This is somewhat in line with Chambers [10] who opines that “when students suffer interruptions to their studies as a result of illness, family difficulties or whatever, their anxiety is often expressed as a feeling of overburden.” Furthermore, time pressure, in tandem with nationality predicted negative outcomes and work efficiency. These findings can, however, can be criticized as being chance or spurious effects, owing to the small effect sizes, partial eta squared (not presented). Furthermore, if corrections are made for multiple comparisons, the p values are likely to be no longer significant. These cast doubts on these findings and calls for further research with much larger samples. Finally, this study showed that nationality did not predict positive outcomes and this finding is in concord with findings from a cross-cultural occupational study [38].

4.1 Limitations

It has been stated in this study that time pressure is not synonymous with student workload. Although, previous research has established significant links between the two concepts and literature has shown that time is very pivotal to how workload is perceived, they are quite different. The implication of this difference, especially for the current study, is that time pressure can only present an aspect of the effects of workload on well-being. Particularly in this situation where the roles of nationality were also investigated, an actual measure(s) of workload would have given a clearer picture of the effects of nationality and workload on well-being. Furthermore, this study only relied on subjective outcomes. While subjective perceptions of well-being are very important as they are relative from one individual to another, it would have been helpful to include measure like students’ academic performance (in terms of Grade Point Average GPA). To this end, it is suggested that future studies should incorporate actual measures of workload and objective outcomes (like academic attainment as measured by GPA) addition to nationality, time pressure and other variables (predictors and outcomes) investigated in the current study. Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of the study which makes it impossible to established causality. It is thus suggested that future studies should be longitudinal in nature while incorporating all the aforementioned variables.

5 Conclusion

Time pressure is very central to student workload. This study has revealed that time pressure, on its own, predicted course stress. Time pressure in tandem with nationality predicted work efficiency and negative well-being outcomes. Time pressure directly or indirectly predicted three of the four outcomes measured. As time pressure plays a huge role in student workload, it is a critical issue that needs to be managed to optimize student well-being. Furthermore, nationality predicted negative well-being out-comes, and in tandem with time pressure and other student well-being predictors predicted all the outcomes. This indicates that cultural differences do play significant roles in the prediction of well-being especially when combined with predictors - emphasizing the contextual factors that influence student well-being.

References

Wickens, C.D., Hollands, J.G., Banbury, S., Parauraman, R.: Engineering Psychology and Human Performance, 4th edn. Routledge, Abingdon (2016)

Byrne, A.: The effect of education and training on mental workload in medical education. In: Longo, L., Leva, M.Chiara (eds.) H-WORKLOAD 2018. CCIS, vol. 1012, pp. 258–266. Springer, Cham (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14273-5_15

Fan, J., Smith, A.P.: The impact of workload and fatigue on performance. In: Longo, L., Leva, M.C. (eds.) H-WORKLOAD 2017. CCIS, vol. 726, pp. 90–105. Springer, Cham (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61061-0_6

Bowyer, K.: A model of student workload. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 34(3), 239–258 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080x.2012.678729

Kingsland, A.J.: Time expenditure, workload, and student satisfaction in problem-based learning. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 1996(68), 73–81 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.37219966811

Kember, D.: Interpreting student workload and the factors which shape students’ perceptions of their workload. Stud. High. Educ. 29(2), 165–184 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507042000190778

Kyndt, E., Berghmans, I., Dochy, F., Bulckens, L.: ‘Time is Not Enough.’ Workload in Higher Education: a student perspective. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 33(4), 684–698 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.863839

Devlin, M., Gray, K.: In their own words: a qualitative study of the reasons Australian university students plagiarize. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 26(2), 181–198 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701310805

Baeten, M., Kyndt, E., Struyven, K., Dochy, F.: Using student-centred learning environments to stimulate deep approaches to learning: factors encouraging or discouraging their effectiveness. Educ. Res. Rev. 5(3), 243–260 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.06.001

Chambers, E.: Work-load and the quality of student learning. Stud. High. Educ. 17(2), 141–153 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079212331382627

Souto-Iglesias, A., Baeza_Romero, M.: Correction to: a probabilistic approach to student workload: empirical distributions and ECTS. High. Educ. 76(6), 1027–1027 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0270-1

Ramsden, P.: Improving teaching and learning in higher education: the case for a relational perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 12(3), 275–286 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1080/03075078712331378062

Smith, A.P.: Student Workload, Wellbeing and Academic Attainment Submitted

Bergin, A., Pakenham, K.: Law student stress: relationships between academic demands, social isolation, career pressure, study/life imbalance and adjustment outcomes in law students. Psychiatry Psychol. Law 22(3), 388–406 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2014.960026

Pritchard, M., McIntosh, D.: What predicts adjustment among law students? A longitudinal panel study. J. Soc. Psychol. 143(6), 727–745 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540309600427

Ryan, R.M., Deci, E.L.: On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 141–166 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Caccioppo, J.T., Bernsto, G.B.: The affect system: architecture and operating characteristics. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 8, 133–137 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00031

Smith, A.P., Wadsworth, E.A.: A holistic approach to stress and wellbeing. Part 5: what is a good job? Occup. Health (At work) 8, 25–27 (2011)

Mark, G., Smith, A.P.: Stress models: a review and suggested new direction. In: Houdmont, J., Leka, S. (eds.) Occupational Health Psychology, vol. 3, pp. 111–144. Nottingham University Press, Nottingham (2008)

Zurlo, M.C., Vallone, F., Smith, A.P.: Effects of individual differences and job characteristics on the psychological health of Italian nurses. Europe’s J. Psychol. 14, 159–175 (2018). https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v14i1.1478

Smith, A.P.: Cognitive fatigue and the wellbeing and academic attainment of university students. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 24(2), 1–12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.9734/jesbs/2018/39529

Williams, G.M., Smith, A.P.: A longitudinal study of the well-being of students using the student wellbeing process questionnaire (Student WPQ). J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 24(4), 1–6 (2018). https://doi.org/10.9734/jesbs/2018/40105

Omosehin, O., Smith, A.P.: Adding new variables to the well-being process questionnaire (WPQ) – further studies of workers and students. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 28(3), 1–19 (2018). https://doi.org/10.9734/jesbs/2018/45535

Smith, A.P., Smith, H.N.: Workload, fatigue and performance in the rail industry. In: Longo, L., Leva, M.C. (eds.) H-WORKLOAD 2017. CCIS, vol. 726, pp. 251–263. Springer, Cham (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61061-0_17

Chambel, M.J., Curral, L.: Stress in academic life: work characteristics as predictors of student well-being and performance. Appl. Psychol. 54(1), 135–147 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00200.x

Karasek, R., Theorell, T.: Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity and the Reconstruction of Working Life. Basic Books, New York (1990)

Cotton, S.J., Dollard, M.F., de Jonge, J.: Stress and job design: satisfaction, well-being and performance in university students. Int. J. Stress. Manag. 9(3), 147–162 (2002)

Perrewé, P.L., Zellars, K.L.: An examination of attributions and emotions in the transactional approach to the organizational stress process. J. Organ. Behav. 20(5), 739–752 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-1379(199909)20:5%3c739:aid-job1949%3e3.0.co;2-c

Ballard, B.: Academic adjustment: the other side of the export dollar. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 6(2), 109–119 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436870060203

Mullins, G., Quintrell, N., Hancock, L.: The experiences of international and local students at three australian universities. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 14(2), 201–231 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436950140205

Alharbi, E., Smith, A.: Review of the literature on stress and wellbeing of international students in English-speaking countries. Int. Educ. Stud. 11(6), 22 (2018). https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v11n6p22

Sheldon, K.M., Krieger, L.S.: Does legal education have undermining effects on law students? Evaluating changes in motivation, values, and well-being. Behav. Sci. Law 22(2), 261–286 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.582

Williams, G., Pendlebury, H., Thomas, K., Smith, A.: The student well-being process questionnaire (student WPQ). Psychology 08(11), 1748–1761 (2017). https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2017.811115

Williams, G., Thomas, K., Smith, A.: Stress and well-being of university staff: an investigation using the demands-resources-individual effects (DRIVE) model and well-being process questionnaire (WPQ). Psychology 08(12), 1919–1940 (2017). https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2017.812124

Kohn, P.M., Lafreniere, K., Gurevich, M.: The Inventory of College Students’ Recent Life Experiences: a decontaminated hassles scale for a special population. J. Behav. Med. 13(6), 619–630 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00844738

Bodenhorn, N., Miyazaki, Y., Ng, K., Zalaquett, C.: Analysis of the inventory of college students’ recent life experiences. Multicult. Learn. Teach. 2(2) (2007). https://doi.org/10.2202/2161-2412.1022

Cohen, S., Mermelstein, R., Kamarck, T., Hoberman, H.: Measuring the Functional Components of Social Support (1986)

Omosehin, O., Smith, A.: Nationality, ethnicity and the well-being process in occupational samples. Open J. Soc. Sci. 07(05), 133–142 (2019). https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2019.75011

Connor, K.M., Davidson, J.R.: Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 18(2), 76–82 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Student Well-being Questionnaire

The following questions contain a number of single-item measures of aspects of your life as a student and feelings about yourself. Many of these questions will contain examples of what thoughts/behaviours the question is referring to which are important for understanding the focus of the question, but should be regarded as guidance rather than strict criteria. Please try to be as accurate as possible, but avoid thinking too much about your answers, your first instinct is usually the best.

-

1.

Overall, I feel that I have low self-esteem (For example: At times, I feel that I am no good at all, at times I feel useless, I am inclined to feel that I am a failure)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

2.

On a scale of one to ten, how depressed would you say you are in general? (e.g. feeling ‘down’, no longer looking forward to things or enjoying things that you used to)

Not at all depressed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Extremely depressed

-

3.

I have been feeling good about my relationships with others (for example: Getting along well with friends/colleagues, feeling loved by those close to me)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

4.

I don’t really get on well with people (For example: I tend to get jealous of others, I tend to get touchy, I often get moody)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

5.

Thinking about myself and how I normally feel, in general, I mostly experience positive feelings (For example: I feel alert, inspired, determined, attentive)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

6.

In general, I feel optimistic about the future (For example: I usually expect the best, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad, It’s easy for me to relax)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

7.

I am confident in my ability to solve problems that I might face in life (For example: I can usually handle whatever comes my way, If I try hard enough I can overcome difficult problems, I can stick to my aims and accomplish my goals)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

8.

I feel that I am laid-back about things (For example: I do just enough to get by, I tend to not complete what I’ve started, I find it difficult to get down to work)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

9.

I am not interested in new ideas (For example: I tend to avoid philosophical discussions, I don’t like to be creative, I don’t try to come up with new perspectives on things)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

10.

Overall, I feel that I have positive self-esteem (For example: On the whole I am satisfied with myself, I am able to do things as well as most other people, I feel that I am a person of worth)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

11.

I feel that I have the social support I need (For example: There is someone who will listen to me when I need to talk, there is someone who will give me good advice, there is someone who shows me love and affection)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

12.

Thinking about myself and how I normally feel, in general, I mostly experience negative feelings (For example: I feel upset, hostile, ashamed, nervous)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

13.

I feel that I have a disagreeable nature (For example: I can be rude, harsh, unsympathetic)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

Negative Coping Style

Blame Self

-

14.

When I find myself in stressful situations, I blame myself (e.g. I criticize or lecture myself, I realise I brought the problem on myself).

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

Wishful Thinking

-

15.

When I find myself in stressful situations, I wish for things to improve (e.g. I hope a miracle will happen, I wish I could change things about myself or circumstances, I daydream about a better situation).

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

Avoidance

-

16.

When I find myself in stressful situations, I try to avoid the problem (e.g. I keep things to myself, I go on as if nothing has happened, I try to make myself feel better by eating/drinking/smoking).

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

Personality

-

17.

I prefer to keep to myself (For example: I don’t talk much to other people, I feel withdrawn, I prefer not to draw attention to myself)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

18.

I feel that I have an agreeable nature (For example: I feel sympathy toward people in need, I like being kind to people, I’m co-operative)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

19.

In general, I feel pessimistic about the future (For example: If something can go wrong for me it will, I hardly ever expect things to go my way, I rarely count on good things happening to me)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

20.

I feel that I am a conscientious person (For example: I am always prepared, I make plans and stick to them, I pay attention to details)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

21.

I feel that I can get on well with others (For example: I’m usually relaxed around others, I tend not to get jealous, I accept people as they are)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

22.

I feel that I am open to new ideas (For example: I enjoy philosophical discussion, I like to be imaginative, I like to be creative)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

23.

Overall, I feel that I am satisfied with my life (For example: In most ways my life is close to my ideal, so far I have gotten the important things I want in life)

Disagree strongly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree strongly

-

24.

On a scale of one to ten, how happy would you say you are in general?

Extremely unhappy 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Extremely happy

-

25.

On a scale of one to ten, how anxious would you say you are in general? (e.g. feeling tense or ‘wound up’, unable to relax, feelings of worry or panic)

Not at all anxious 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Extremely anxious

-

26.

Overall, how stressful is your life?

Not at all stressful 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very Stressful

Please consider the following elements of student life and indicate overall to what extent they have been a part of your life over the past 6 months. Remember to use the examples as guidance rather than trying to consider each of them specifically:

-

27.

Challenges to your development (e.g. important decisions about your education and future career, dissatisfaction with your written or mathematical ability, struggling to meet your own or others’ academic standards).

Not at all part of my life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very much part of my life

-

28.

Time pressures (e.g. too many things to do at once, interruptions of your school work, a lot of responsibilities).

Not at all part of my life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very much part of my life

-

29.

Academic Dissatisfaction (e.g. disliking your studies, finding courses uninteresting, dissatisfaction with school).

Not at all part of my life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very much part of my life

-

30.

Romantic Problems (e.g. decisions about intimate relationships, conflicts with boyfriends’/girlfriends’ family, conflicts with boyfriend/girlfriend).

Not at all part of my life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very much part of my life

-

31.

Societal Annoyances (e.g. getting ripped off or cheated in the purchase of services, social conflicts over smoking, disliking fellow students).

Not at all part of my life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very much part of my life

-

32.

Social Mistreatment (e.g. social rejection, loneliness, being taken advantage of).

Not at all part of my life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very much part of my life

-

33.

Friendship problems (e.g. conflicts with friends, being let down or disappointed by friends, having your trust betrayed by friends).

Not at all part of my life 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very much part of my life

Please state how much you agree or disagree with the following statements:

-

34.

There is a person or people in my life who would provide tangible support for me when I need it (for example: money for tuition or books, use of their car, furniture for a new apartment).

Strongly Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Strongly Agree

-

35.

There is a person or people in my life who would provide me with a sense of belonging (for example: I could find someone to go to a movie with me, I often get invited to do things with other people, I regularly hang out with friends).

Strongly Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Strongly Agree

-

36.

There is a person or people in my life with whom I would feel perfectly comfortable discussing any problems I might have (for example: difficulties with my social life, getting along with my parents, sexual problems).

Strongly Disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Strongly Agree

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Omosehin, O., Smith, A.P. (2019). Do Cultural Differences Play a Role in the Relationship Between Time Pressure, Workload and Student Well-Being?. In: Longo, L., Leva, M. (eds) Human Mental Workload: Models and Applications. H-WORKLOAD 2019. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1107. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32423-0_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32423-0_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-32422-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-32423-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)