Abstract

How is inequality associated to social gradients in health such as overweight/obesity? Inconclusive findings and misunderstanding regarding the association between inequality and overweight/obesity impair attempts to reduce social gradients in obesity. In this chapter, we discuss various findings from research on food choices and consumption in situations broadly associated with inequality; that is, environmental scarcity and resource competition, relative deprivation and wealth, and social class distinctions. Based on a review of social and evolutionary psychological theories, we present a model that describes a diverse set of psychological mechanisms that may underlie the effect of experienced inequality on eating behaviors. In particular, we discuss how perceptions of environmental harshness increase motivation for calories, how relative status differences can trigger negative emotions that increase caloric intake, and how food consumption can be motivated by socioeconomic class distinctions that are heightened under conditions of inequality. We conclude with an integration of these different findings and propose future directions that can address current limitations in interventions aimed at reducing social inequalities in health.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

We know that more unequal societies have worse health outcomes, such as higher obesity prevalence. In recent years, researchers have explored how and for whom inequality affects food intake and ultimately leads to weight gain. Possibly stemming from the large diversity of measures and research methods used across disciplines, the findings are somewhat contradictory.

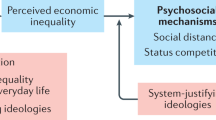

In an attempt to organize the literature, in this chapter, we provide an overview of (social) psychological theories and studies that attempt to explain psychological mechanisms through which conditions of inequality may impact eating behaviors. To complement the findings from psychological research, we borrow from related domains such as sociological, consumer, and public health research. We first discuss how inequality triggers perceptions of environmental harshness and resource competition that can increase desire for caloric food. We then consider how inequality increases the salience of status differences and review studies on the influence of social comparisons on eating behavior. Lastly, we discuss how inequality enhances social-class distinctions that encourage food consumption based on class norms. Where possible, we explore psychological processes that can explain how and why these perceptions and experiences impact eating behavior.

Based on this review, we present a model that encompasses the diversity of psychological mechanisms that are thought to underlie the effect of experienced inequality on eating behaviors. Understanding how inequality and obesity are associated is critical, considering (a) the expected growing rates of both inequality and obesity (Breda, Webber, & Kirby, 2015; Alvaredo, Atkinson, Pikkety, Saez, & Zucman, 2018), and (b) the observation that existing approaches for reducing social gradients in health have proven relatively unsuccessful or, worse, have exacerbated health inequalities (Darmon, Lacroix, Muller, & Ruffieux, 2014; Frohlich & Potvin, 2008).

Challenges in Research on Inequality and Obesity

Rising levels of inequality and obesity within developed countries have attracted interest among both public and academic communities. Research findings point to a positive association between country-level inequality and the prevalence of physical and mental conditions in those countries (Subramanian & Kawachi, 2004; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009), including obesity (Pickett, Kelly, Brunner, Lobstein, & Wilkinson, 2005). Being overweight or obese involves an abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat that increases a person’s risk of developing other non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease (WHO, 2017a). In 2016, the overweight and obesity prevalence worldwide was 13% and 39%, respectively (WHO, 2017b), and tended to be higher in countries with higher income inequality (Pickett et al., 2005).

Most reports on the association between inequality and obesity rely on country-level, cross-sectional data, comparing countries varying along inequality and examining the correlation with the obesity prevalence in these countries. The findings resulting from such analyses vary as a function of what is measured and which countries are examined. For instance, the positive association between income inequality and obesity in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries almost disappeared when the US and Mexico are excluded from analyses (Su, Esqueda, Li, & Pagán, 2012). Furthermore, the association between obesity and inequality was weak compared to the association of obesity with indicators of economic insecurity (i.e., security from unemployment, illness, single-parent poverty, and poverty in old age; Offer, Pechey, & Ulijaszek, 2010). Comparisons between country-level and individual-level measures are difficult given that inequality pertains to social systems whereas socioeconomic status (SES) characterizes individuals or groups within those systems (Ellison, 2002).

Although many of these cross-sectional studies rely on large data sets and sophisticated analyses, their correlational nature makes it daring to draw causal conclusions, even more so when it comes to identifying the relevant psychological mechanisms involved. Only recently have researchers started employing experimental methods allowing for firmer causal interpretation and assessment of underlying processes (Goudeau, Autin, & Croizet, 2017).

In these experiments, inferences about inequality are usually made by making comparisons between individuals varying in status and by measuring snapshot moments of food consumption rather than weight and/or obesity status. Participants are typically randomly allocated to experimental conditions in which the experience of relative scarcity or deprivation, or relative wealth is or is not induced. Although this approach is lower in ecological validity than the epidemiological approach, it allows for causal examination and more precise examination of relationships between variables.

Gaining insights into the processes underlying the association between inequality and obesity could stimulate the development of successful interventions, which tend to involve reductions in financial cost, or nutrition education, and have unsubstantial effects (Capacci et al., 2012; Powell & Chaloupka, 2009). The following sections discuss research findings that may provide some answers to improve such approaches.

Harsh Environments Increase Desire for Calories: An Evolutionary Perspective

In environments with high inequality, richer people own a relatively larger amount of the available resources. For instance, in the US, recent estimates suggest that the share of income of the bottom half of the population is 12%, whereas the share of the 1% at the top is 20% (Piketty, Saez, & Zucman, 2018). If resources are unequally distributed among individuals in society, perceptions of resource scarcity and competition can ensue (Roux, Goldsmith, & Bonezzi, 2015). According to an evolutionary psychological theory, life-history theory, perceptions of environmental harshness and instability attune organisms to collect as many resources as possible in order to secure survival and reproduction (Del Guidice, Gangestad, & Kaplan, 2015; Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach, & Schlomer, 2009).

It has been suggested that resources such as status, money, and food share a common valuation system in terms of their allocation for growth, reproduction, and energy (Brinberg & Wood, 1983; Foa & Foa, 1974). In line with this proposition, there is evidence that a lack of money induces desire for food (Laran & Salerno, 2013; Levy & Glimcher, 2012).

Indeed, findings from experimental studies indicate that perceptions of environmental harshness increase desire for food, specifically for food that is high in calories (Bratanova, Loughnan, Klein, Claassen, & Wood, 2016; Briers & Laporte, 2013; Laran & Salerno, 2013; Swaffield & Roberts, 2015). High-calorie foods are more beneficial to survival and are perceived as more valuable in terms of energy provision and as substitutes for monetary resources (Briers, Pandelaere, Dewitte, & Warlop, 2006; Tang, Fellows, & Dagher, 2014). To illustrate, using a within-subjects design, Swaffield and Roberts (2015) examined how reading a scenario about a harsh or safe environment altered the desirability of 30 food items across different categories: grains, dairy, fruits, vegetables, meat, poultry, and sweets. Participants reported their desire for the foods before and after reading the scenarios. The results showed that high-calorie foods became more desirable under conditions of environmental harshness but not when the environment was perceived as relatively safe.

Other studies suggest that the negative consequences of inequality are particularly high for individuals who have grown up with limited resources or in poorer environments. Experiences of harshness in developmental periods condition behavioral patterns that are adaptive in those contexts. For instance, individuals who have grown up in more deprived neighborhoods show greater behavioral disinhibition (Paál, Carpenter, & Nettle, 2015). Exposure to harsh conditions in early-life results in increased sensitivity and responsiveness to cues signaling harshness (Griskevicius et al., 2013). This is because in stressful conditions, responses are driven by formed habits rather than reflective processes (Dallman, 2009; Schwabe & Wolf, 2009).

Research on environmental scarcity and eating behaviors has mostly focused on food insecurity: not having adequate physical, social, or economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food for an active and healthy life (Dinour, Bergen, & Yeh, 2007). Findings indicate that experiencing food insecurity early in life is associated with dysregulated food intake later in life; for instance, eating regardless of one’s energy need as a result of fear that food will be scarce in the future (Dhurandhar, 2016; Hill, Prokosch, DelPriore, Griskevicius, & Kramer, 2016; Nettle, Andrews, & Bateson, 2017).

Likewise, Hill, Rodeheffer, DelPriore, and Butterfield (2013) propose that individuals who have grown up with limited financial resources or in disadvantaged neighborhoods do not necessarily eat more or more unhealthily in general, but only when presented with cues in the environment that signal harsh conditions. These researchers randomly assigned female participants to a condition in which they experienced environmental harshness or to a control condition. For instance, in one of the environmental harshness conditions, participants had to read a newspaper article describing an increase in the homicide rate. The findings showed that for participants who experienced more stressful childhood environments, harshness cues increased desire for food and diminished desire to restrict calories and prevent weight gain. In contrast, for participants who experienced less stressful childhood environments, harshness cues diminished desire for food and increased desire to restrict calories and prevent weight gain. Desire for food, for restricting calories, or preventing weight gain did not differ between participants who had experienced less or more stressful childhood environments in the control condition.

The implication of the above findings is that perceptions of environmental harshness triggered by rising inequality may increase desire for calories, but more likely so for individuals who have grown up in disadvantaged environments (and who are also more likely to occupy disadvantaged positions in society later in life).

Relative Status Comparisons Trigger Negative Emotions That Stimulate Food Intake

Inequality does not only increase the distance between income or wealth levels among individuals in a society, but also affects individual perceptions of position vis-à-vis other individuals or groups (Kraus, Tan, & Tannenbaum, 2013). The higher the inequality, the higher the salience of status and class differences between individuals and groups in a society (Cheung & Lucas, 2016; Kraus, Park, & Tan, 2017).

Comparisons with higher-status individuals or groups lead to a sense of relative deprivation regarding economic, political, or social resources (Festinger, 1954; Flynn, 2011). And feeling less well-off compared to others can elicit negative feelings such as resentment or shame (Bernstein & Crosby, 1980; Kim, Callan, Gheorghiu, & Matthews, 2016; Kraus & Park, 2014). Finally, negative affect can produce a desire for comfort foods: tasty foods that are high in calories, and that trigger positive affect and lower the physiological stress response (Adam & Epel, 2007; Dallman, 2009; Tomiyama, Dallman, & Epel, 2011).

Experimental studies examining experiences of lower or higher relative status, expose participants to such experiences by showing them a ladder representing relative ranks of individuals in their society (see Fig. 1). To make participants experience relative deprivation they are asked to contrast themselves to people at the top of the ladder who are the “best off” in society. On the contrary, in order to make them feel relatively wealthy, they are asked to contrast themselves to people who are “the worst off” in society, positioned at the bottom of the ladder.

MacArthur scale of subjective social status used to manipulate perceptions of relative lower versus higher status. Participants are asked to compare themselves to others in society who are the best off or the worst off (Chatelard et al., 2014)

Findings from studies in which this (or a comparable) manipulation was used, all showed that relative deprivation was associated with higher caloric intake (e.g., Bratanova et al., 2016; Cheon & Hong, 2017), suggesting that experiencing a relatively lower status position leads individuals to consume more calories. These results imply that inequality makes individuals with lower status consume more calories, possibly leading to weight gain, and subsequent social gradients in overweight/obesity.

Of equal interest involves the question of why relative deprivation leads to increased caloric intake. Many of the studies examined possible explanations for this association and found that relative deprivation negatively affects mood (Cheon & Hong, 2017), decreases feelings of power and pride (Cardel et al., 2016), and increases social anxiety (Bratanova et al., 2016), perceptions of unfairness (Sim, Lim, Forde, & Cheon, 2018), feelings of inferiority, and unpleasant affect (Sharma & Alter, 2012). However, only one study among them formally assessed mediation by a psychological measure. In this experiment by Bratanova et al. (2016), participants were told they would have to interact with students coming from a more deprived (relative deprivation condition), more affluent (relative wealth condition), or equal background (control condition). They were then asked to participate in a seemingly unrelated experiment in which they were provided with snacks. The findings showed that both participants who felt relatively deprived or wealthy reported anxiety due to being looked down on (e.g., “I worry that others will look down on my possessions”) or being envied (e.g., “I worry that that other people will envy my privileged background”), respectively. These feelings of anxiety mediated the influence of discrepant relative status (versus equal status) on higher caloric intake. And this relationship, in turn, was moderated by participants’ score on a Need to Belong measure: Higher desire to fit in and be accepted by peers made participants more susceptible to caloric intake as a result of inequality-induced anxiety.

The idea that lower-status positions are associated with food intake due to anxiety or stress is not recent (for a review, see Moore & Cunningham, 2012). Less research, however, has focused on how inequality triggers social anxiety in higher-status individuals (Layte & Whelan, 2014). A possible explanation is that they experience social exclusion because they are resented (Kim, Callan, Gheorghiu, & Skylark, 2018) or envied for their position (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002; see also Fiske & Durante, chapter “Mutual Status Stereotypes Maintain Inequality”).

Caloric intake due to status-related stress can result in weight gain, but stress also modulates metabolic pathways that make humans more likely to gain weight (Dallman, 2009; Rosmond, Dallman, & Bjorntorp, 1998). This is corroborated by findings from animal studies on social hierarchies that indicate that, besides an increased preference for higher-calorie foods, some species store more body fat when they experience bouts of lower status (Arce, Michopoulos, Shepard, Ha, & Wilson, 2010; Foster, Solomon, Huhman, & Bartness, 2006).

In particular, results from two recent studies using the ladder manipulation indicate that relative status may be associated with changes in sensory perception as well as appetite-regulating blood hormones. In one study, researchers found that participants allocated to a lower-status condition and to a control condition were able to distinguish between versions of a soy milk drink that differed in energy density, but that participants in a higher-status condition did not (Cheon, Lim, McCrickerd, Zaihan, & Forde, 2018). This suggests that at the top of the social ladder, energy may not be a priority in food selection. Findings from the other study, which consisted of a within-subjects design with experimental sessions scheduled at least one week apart, indicated that blood levels of participants who had been induced to feel relatively lower in status contained increased levels of active ghrelin (a hormone signaling hunger), as compared to a baseline measure of each participant’s level (Sim, Lim, Leow, & Cheon, 2018). No change was observed for hormones indicating satiety (i.e., polypeptide and insulin). And in the control condition, blood levels did not differ between the baseline measurement and the measurement after the manipulation.

These two studies suggest that both lower and higher status may influence sensory and bodily processes. The diverging results indicate that sensory discrimination and appetite-regulating hormones work independently from each other and are possibly influenced by different characteristics of relative status.

Socially Stratified Symbolic Values of Food Produce Inequalities in Food Consumption

An additional consequence of the increased salience of status differences under conditions of inequality is the emergence and maintenance of social classes (Kraus et al., 2013). Social classes are defined by the structural, economic, or cultural components that lead to the unequal divisions and dispositions that exist within society (Crompton, 2006). In turn, social classes provide unique models for normative behavior and self-expression that are used to construct a social identity (Stephen & Townsend, 2013). The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1979) was one of the first to describe how preferences for food products are shaped by differences in economic, social, and cultural capital across social classes. Since then, the social context of food intake has attracted interest among social psychological researchers, whose results show that our social environment exerts a great influence on what we eat: We model the eating behavior of people around us (Vartanian, Spanos, Herman, & Polivy, 2015), especially those who belong to our social group (Cruwys, Bevelander, & Hermans, 2015).

Psychological research on social identities and food intake mainly focuses on disadvantaged positions related to race/ethnicity or gender (e.g., Guendelman, Cheryan, & Monin, 2011; Oyserman, Fryberg, & Yoder, 2007) but rarely considers social class. However, it is clear that identity threats associated with these disadvantaged positions are also experienced by individuals with lower socioeconomic status (Croizet & Claire, 1998; Fiske et al., 2002).

The lack of studies is surprising given that findings from other research domains indicate that social class does not only influence what we eat; our food choices shape our self- and group-identity, and determine what we communicate about ourselves to others in our environment (Sato, Gittelsohn, Unsain, Roble, & Scagliusi, 2016). For instance, a consumer research study found that when men have to choose a steak in a public setting, they avoid picking the “ladies’ cut” steak to keep their image of manliness intact (White & Dahl, 2006). Different motives underlie consumption as a function of social groups, for instance, the consumption of products’ characteristic of a particular group in order to affiliate with that group and distinguish oneself from another group (Guendelman et al., 2011; Lee & Shrum, 2012; Mead, Baumeister, Stillman, Rawn, & Vohs, 2011) or to signal one’s rank in the social hierarchy (Veblen, 1899).

People generally believe that individuals from lower social classes eat more unhealthily, and this lay-belief is shared among lower-class individuals themselves (Bugge, 2011; Davidson, Kitzinger, & Hunt, 2006). In a recent study, we asked 200 US and UK residents, with diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, to evaluate 65 food items in terms of whether they associated them as belonging to lower- or higher-status individuals or groups, and to rate them on scales of healthiness, caloric content, and price (Claassen, Klein, & Corneille, 2019). Evaluations of higher status were positively correlated with evaluations of healthiness, r(63) = 0.541, lower caloric content, r(63) = −0.400, and higher price, r(63) = 0.812. All correlations were statistically significant with p-values under 0.001. For instance, fish sticks, hotdog, and donut were perceived as lower-status unhealthy foods, whereas asparagus, avocado, and sushi were perceived as higher-status healthy foods.

The above implies that identifying as a low- or high-class individual can lead to specific food choices through beliefs and norms regarding foods, which then become ingrained within a particular social class identity. Findings from a study in the Netherlands showed that consumption of “superfoods” is associated with status signaling for higher-status individuals. Higher levels of income and education were related to higher consumption of spelt products, quinoa, goji berries, chia seeds, and wheatgrass (Oude Groeniger, van Lenthe, Beenackers, & Kamphuis, 2017). The associations between income, education, and consumption of these foods were attenuated when participation in cultural events (e.g., museum, theater, or concert visits) was statistically controlled for. This suggests that the consumption of these superfoods serves a similar purpose as participating in cultural events: They increase one’s cultural and symbolic status. Another illustration of a similar phenomenon is the “buying into” other culture’s food heritage by consuming exotic and culturally diverse foods that are inaccessible to lower classes (Wills, Backett-Milburn, Roberts, & Lawton, 2011); for instance, spices such as nutmeg and ginger were hard to get in the past and consuming them was reserved for the rich (van der Veen, 2003).

The few studies that examine the symbolic meaning of food in individuals with lower SES, suggest that they may be tempted to reject healthy foods if they are perceived not to fit with the consumption patterns of their ingroup. In a focus group with young adolescents from communities in the UK, one of the participants stated: “…all the healthy stuff”, like “water, banana, yoghurt, cheese strings,” is what geeks would bring to school “because they would want you to think they were smart and that” (Stead, McDermott, MacKintosh, & Adamson, 2011, p. 1136). In contrast, participants perceived the consumption of unhealthy foods such as Coke© and crisps as good for their image and as a means to blend in with the crowd, especially the adolescents with lower social status. This suggests that unhealthy foods are regarded as food for the “cool kids” and are consumed as a form of rebellion against the “healthy norm” (Bugge, 2011; Johnston, Rodney, & Szabo, 2012; Oyserman, Smith, & Elmore, 2014).

When given the opportunity to do so, individuals with lower status may aspire to increase their perceived status by consuming particular foods. An experimental manipulation of relative deprivation led participants in that condition to prefer candy bars that were scarce but not candy bars that were available in abundance (Sharma & Alter, 2012). We know from previous research that product scarcity signals expensiveness (Lynn, 1989). Other studies have shown that identifying with lower-status groups increases the desire for higher-status goods (Mazzocco, Rucker, Galinsky, & Anderson, 2012), and for foods that may increase one’s perceived social status: For instance, foods that signal power and strength such as meat (Chan & Zlatevska, 2019), or products of larger sizes (Dubois, Rucker, & Galinsky, 2012).

However, when inequality is high, social-class boundaries are tightened and social mobility, the extent to which individuals can move from one social class to another, decreases (Day & Fiske, chapter “Understanding the Nature and Consequences of Social Mobility Beliefs”; Wang, Jetten, & Steffens, chapter “Do People Want More Wealth and Status in Unequal Societies?”). This (perceived) stability of social-class boundaries maintains the classed norms regarding healthy diets (as well as body sizes), which tend to be unhealthier among lower social classes (Fikkan & Rothblum, 2012; Godley & McLaren, 2010). Although individuals with lower status are aware of the differences between healthy and unhealthy foods, a healthy diet needs to become congruent with their lower-class identity for them to engage in behaviors promoting healthier food choices (Oyserman et al., 2014; Stephens, Markus, & Fryberg, 2012).

The existing research on classed food choices is limited, however, and focuses on specific groups. This restricts the generalizability of the findings to other social and cultural groups within and between societies. Moreover, the studies only allow for analysis of observed behaviors regarding food choices in service of social affiliation or distinction. Examination of the underlying motives and psychological processes could, for instance, provide information on whether social distinction by higher-status individuals is motivated by the fear of losing status (see Scheepers & Ellemers, chapter “Explaining Defensiveness to the Resolution of Social Inequality in Members of Dominant Groups”), or whether freedom to choose instills the fear of making the wrong choice (Bauman, 1988; Warde, 1994). This would entail that the constriction of social classes due to increasing inequality can also be detrimental to the health of higher-class individuals, albeit for different reasons than for individuals of lower class.

Future research could examine processes related to independent and interdependent social orientations, provided that these orientations are associated with tendencies to affiliate with others or to distinguish the self from them (Sweet, 2011; van der Veen, 2003) and are affected by societal inequality (Loughnan et al., 2011; Sánchez-Rodríguez, Willis, & Rodríguez-Bailón, 2017) as well as individual social status (Kraus, Piff, & Keltner, 2011; Stephens, Markus, & Townsend, 2007; Woolley & Fishbach, 2016).

A Proposed Model of Associations Between Inequality and Eating Behaviors

The reviewed literature indicates that under conditions of higher inequality, the available resources in society are (perceived as) accumulating at the top of the social rank, signaling scarcity and competition for resources. In addition, inequality makes status differences between individuals and groups in society more salient, which activates social comparisons that can lead to negative emotions, higher stress, or negative self-perceptions. Furthermore, when the distance between different social groups increases, it becomes harder for individuals to transition from one group to the other. The reviewed literature indicates that the psychological processes resulting from these status differences can negatively impact eating behaviors, for instance, by increasing one’s physical and psychological desire for calories or by encouraging the selection of foods contingent on social-class norms. Figure 2 provides an overview of the discussed mechanisms.

The influences of inequality on the different psychological processes ascribed to environmental harshness, relative status differences, and increased social-class salience are not mutually exclusive. Although they theoretically describe different behavioral patterns, it is possible that they are driven by similar processes. In particular, negative emotions or increased stress levels could be underlying mechanisms linking inequality-related perceptions with increased caloric intake. The findings from the reviewed experimental studies suggest that both environmental harshness and negative social comparisons are associated with more negative affect or higher stress levels. This is consistent with studies that recorded cardiovascular reactivity similar to that in response to environmental threat, in participants who made upward social comparisons (Mendes, Blascovich, Major, & Seery, 2001) or who were placed in disadvantaged positions compared to an opponent in a game (Cardel et al., 2016).

In addition, other findings indicate that engaging in social distinction under the burden of low material resources and low social mobility can be stressful and can deplete cognitive resources (Johnson, Richeson, & Finkel, 2011; Sweet, 2011). Linda Tirado in her autobiographical essay on poverty, Hand to Mouth (2014), described failed attempts of climbing the social ladder: “We have learned not to try too hard to be middle-class. It never works out well and always makes you feel worse for having tried and failed yet again. Better not to try. It makes more sense to get food that you know will be palatable and cheap and that keeps well. Junk food is a pleasure that we are allowed to have; why would we give that up? We have very few of them.” These observations corroborate findings on decision-making under conditions of poverty, which suggest that increased stress levels can trigger motivation to obtain calories or can decrease cognitive capacity to, for instance, resist tempting foods (Haushofer & Fehr, 2014; Shah, Mullainathan, & Shafir, 2012; Spears, 2011).

Promisingly, in a series of experiments we found that higher relative income position can overcome the detrimental influence of low absolute income on impulsivity (Claassen, Corneille, & Klein, 2019). More specifically, participants with lower incomes were less likely to delay gratification of monetary and food rewards than participants with higher incomes, but they behaved equally impulsive as richer participants when they engaged in a downward social comparison. This suggests that relative position may matter most in determining behaviors associated with health promotion and that decreasing inequality could ultimately improve the health of lower-status individuals.

Another question of interest in inequality research concerns who is most affected by inequality: individuals at the bottom of the social ladder, or those at the top? The findings on environmental harshness suggest that inequality can worsen the social gradients in food intake due to lower-status individuals desiring caloric foods. This is corroborated by a recent analysis showing that inequality is only associated with unhappiness and psychological health for individuals who experience financial scarcity (Sommet, Morselli, & Spini, 2018). This emphasizes the double burden of being poor in an unequal society: Poverty in both absolute and relative terms is detrimental to health.

Furthermore, the findings on social-class distinctions also suggest that inequality affects the health of lower-status individuals. Socially stratified symbolic values of food ascribe unhealthier foods to lower classes. Not only does this generate social gradients in health, but these gradients themselves feed back into the inequality cycle by maintaining inequalities in diet patterns and weight status.

Yet, the findings on relative comparisons suggest that both the poor and rich may be affected by inequality: It increases the identity salience of the poor and rich and the tension resulting from wealth differences. Anxiety from social comparisons can provoke an increase in calorie consumption as a coping mechanism for both lower- and higher-status individuals (Bratanova et al., 2016). This resonates with research showing that identity threats lead to food intake and weight gain (Vartanian & Porter, 2016), given that both the poor and rich are stigmatized and subject of stereotype threat (Fiske et al., 2002; Fiske & Durante, chapter “Mutual Status Stereotypes Maintain Inequality”). The idea that inequality increases anxiety for both lower- and higher-status individuals is corroborated by a multilevel study whose findings showed that the income–anxiety gradient was the same across all countries no matter their level of inequality, but that absolute levels of reported anxiety were higher in more unequal countries (Layte & Whelan, 2014).

Conclusion

The findings discussed in this chapter suggest explanations for why current interventions and policies aimed at decreasing social gradients in health may benefit from inclusion of a psychological perspective (Callan, Kim, & Matthews, 2015; Claassen, Klein, Bratanova, Claes, & Corneille, 2018). These interventions typically focus on reducing financial or educational inequalities. Nevertheless, even if healthy foods were equally accessible to low- and high-status individuals, signs of environmental harshness due to unequal income distributions would still trigger desire for calories. And even if income distributions were equated between the poor and rich, the sociocultural contexts of classed behavior patterns would still remain embedded in society and would still signal class distinctions between individuals (see also the inequality maintenance model of social class proposed by Piff, Kraus, & Keltner, 2018).

Although the findings from experimental studies advance our understanding of the association between inequality and food intake, the downside is that their reliability and generalizability can be called into question: Many studies do not report effect sizes, and when reported, they are small. So are sample sizes for individual studies, which tend to use homogenous highly educated (student) samples. Future studies examining the influence of inequality on food intake should include participants varying in SES. Additionally, replications across different countries and laboratories would decrease the chance of inferring conclusions from false positives (Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011).

Contributors to the literature propose including relative indicators of SES, for instance, subjective SES, when assessing societal inequalities. In addition, the authors of a recent narrative review emphasize the importance of considering adaptive responses and developmental factors (e.g., responses to environmental threat or childhood SES; Caldwell & Sayer, 2018). We believe that it is also important to include symbolic markers of wealth or status, or social class, since these indicators capture unique variance in health inequality (Markus & Stephens, 2017). In country-level analyses, social mobility could be used as an indicator of the level of stratification of a society. Lastly, whereas many studies focus on the negative influence of inequality on the well-being of the poor, there is a reason to believe that inequality can also have detrimental effects on the more advantaged individuals in a society. Capitalizing on this last finding could mobilize resources toward studying and diminishing societal inequalities.

This chapter emphasizes that the relation between inequality and the consumption of unhealthier or caloric foods does not only derive from poor nutritional knowledge, lack of access to healthier foods, or the actual financial cost of these foods. It is also a function of social psychological mechanisms that impinge on perceptions of status and competition in one’s surroundings as well as the symbolic value of food (e.g., as a marker of identity). Any attempt to address this important public health problem would benefit from taking these aspects into account.

References

Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology and Behavior, 91(4), 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011

Arce, M., Michopoulos, V., Shepard, K. N., Ha, Q. C., & Wilson, M. E. (2010). Diet choice, cortisol reactivity, and emotional feeding in socially housed rhesus monkeys. Physiology and Behavior, 101(4), 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.07.010

Bauman, Z. (1988). Freedom. London: Open University Press.

Bernstein, M., & Crosby, F. (1980). An empirical examination of relative deprivation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16, 442–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(80)90050-5

Bourdieu, P. (1979). La distinction. Critique sociale du jugement. Paris: Les éditions de minuit.

Bratanova, B., Loughnan, S., Klein, O., Claassen, A., & Wood, R. (2016). Poverty, inequality, and increased consumption of high calorie food: Experimental evidence for a causal link. Appetite, 100, 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.028

Breda, J., Webber, L., & Kirby, T. (2015). Proportion of overweight and obese males and female to increase in most European countries by 2030, say latest projections by WHO. World Health Organisation. Retrieved from http://www.ernaehrungsmedizin.blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ECO2015WEDSPRESSWHO4.pdf

Briers, B., & Laporte, S. (2013). A wallet full of calories: The effect of financial dissatisfaction on the desire for food energy. Journal of Marketing Research, 50, 767–781. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.10.0513

Briers, B., Pandelaere, M., Dewitte, S., & Warlop, L. (2006). Hungry for money: The desire for caloric resources increases the desire for financial resources and vice versa. Psychological Science, 17(11), 939–943. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01808.x

Brinberg, D., & Wood, R. (1983). A resource exchange theory analysis of consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 10(3), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.2307/2488805

Bugge, A. B. (2011). Lovin’ it? A study of youth and the culture of fast food. Food, Culture and Society, 14(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174411X12810842291236

Caldwell, A. E., & Sayer, R. D. (2018). Evolutionary considerations on social status, eating behavior, and obesity. Appetite, 132, 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.07.028

Callan, M. J., Kim, H., & Matthews, W. J. (2015). Predicting self-rated mental and physical health: The contributions of subjective socioeconomic status and personal relative deprivation. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01415

Capacci, S., Mazzocchi, M., Shankar, B., Brambila Macias, J., Verbeke, W., Pérez-Cueto, F. J., et al. (2012). Policies to promote healthy eating in Europe: A structured review of policies and their effectiveness. Nutrition Reviews, 70(3), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00442.x

Cardel, M. I., Johnson, S. L., Beck, J., Dhurandhar, E., Keita, A. D., Tomczik, A. C., et al. (2016). The effects of experimentally manipulated social status on acute eating behavior: A randomized, crossover pilot study. Physiology and Behavior, 162, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.024

Chan, E. Y., & Zlatevska, N. (2019). Jerkies, tacos, and burgers: Subjective socioeconomic status and meat preference. Appetite, 132, 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.08.027

Chatelard, S., Bodenmann, P., Vaucher, P., Herzig, L., Bischoff, T., & Burnand, B. (2014). General practitioners can evaluate the material, social and health dimensions of patient social status. PLoS One, 9(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084828

Cheon, B. K., & Hong, Y.-Y. (2017). Mere experience of low subjective socioeconomic status stimulates appetite and food intake. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(1), 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607330114

Cheon, B. K., Lim, E. X., McCrickerd, K., Zaihan, D., & Forde, C. G. (2018). Subjective socioeconomic status modulates perceptual discrimination between beverages with different energy densities. Food Quality and Preference, 68, 258–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.03.010

Cheung, F., & Lucas, R. (2016). Income inequality is associated with stronger social comparison effects: The effect of relative income on life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(2), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.55.7593

Claassen, M., Corneille, O., & Klein, O. (2019). Higher subjective income reduces delay discounting in lower-income individuals. Manuscript in Preparation.

Claassen, M., Klein, O., & Corneille, O. (2019). Tell me what you eat, I’ll tell you what you are: A cross-country analysis of the symbolic value of foods. Manuscript in Preparation.

Claassen, M. A., Klein, O., Bratanova, B., Claes, N., & Corneille, O. (2018). A systematic review of psychosocial explanations for the relationship between socioeconomic status and body mass index. Appetite, 132, 208–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.07.017

Croizet, J. C., & Claire, T. (1998). Extending the concept of stereotype threat to social class: The intellectual underperformance of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(6), 588–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167298246003

Crompton, R. (2006). Class and family. The Sociological Review, 54(4), 658–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00665.x

Cruwys, T., Bevelander, K. E., & Hermans, R. C. J. (2015). Social modeling of eating: A review of when and why social influence affects food intake and choice. Appetite, 86, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.035

Dallman, M. F. (2009). Stress-induced obesity and the emotional nervous system. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 21(3), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2009.10.004

Darmon, N., Lacroix, A., Muller, L., & Ruffieux, B. (2014). Food price policies may improve diet but increase socioeconomic inequalities in nutrition. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 11(66), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1159/000442069

Davidson, R., Kitzinger, J., & Hunt, K. (2006). The wealthy get healthy, the poor get poorly? Lay perceptions of health inequalities. Social Science and Medicine, 62(9), 2171–2182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.010

Del Guidice, M., Gangestad, S. W., & Kaplan, H. S. (2015). Life history theory and evolutionary psychology. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 68–95). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470939376.ch2

Dhurandhar, E. J. (2016). The food-insecurity obesity paradox: A resource scarcity hypothesis. Physiology & Behavior, 162, 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.025

Dinour, L. M., Bergen, D., & Yeh, M.-C. (2007). The food insecurity-obesity paradox: A review of the literature and the role food stamps may play. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(11), 1952–1961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.006

Dubois, D., Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2012). Super size me: Product size as a signal of status. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(6), 1047–1062. https://doi.org/10.1086/661890

Ellis, B. J., Figueredo, A. J., Brumbach, B. H., & Schlomer, G. L. (2009). Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk: The impact of harsh versus unpredictable environments on the evolution and development of life history strategies. Human Nature, 20(2), 204–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9063-7

Ellison, G. (2002). Letting the Gini out of the bottle? Challenges facing the relative income hypothesis. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2018.03.028

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Fikkan, J. L., & Rothblum, E. D. (2012). Is fat a feminist issue? Exploring the gendered nature of weight bias. Sex Roles, 66(9–10), 575–592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0022-5

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315187280

Flynn, S. I. (2011). Relative deprivation theory. In Sociology reference guide: Theories of social movements (pp. 100–110). Pasadena, CA: Salem Press.

Foa, U. G., & Foa, E. B. (1974). Societal structures of the mind. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Foster, M. T., Solomon, M. B., Huhman, K. L., & Bartness, T. J. (2006). Social defeat increases food intake, body mass, and adiposity in Syrian hamsters. American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 290(5), R1284–R1293. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00437.2005

Frohlich, K. L., & Potvin, L. (2008). The inequality paradox: The population approach and vulnerable populations. American Journal of Public Health, 98(2), 216–221. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.114777

Godley, J., & McLaren, L. (2010). Socioeconomic status and Body Mass Index in Canada: Exploring measures and mechanisms. Canadian Review of Sociology, 47(4), 381–403.

Goudeau, S., Autin, F., & Croizet, J. (2017). Studying, measuring and manipulating social class in social psychology: Economic, symbolic and cultural approaches. International Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.52

Griskevicius, V., Ackerman, J. M., Cantú, S. M., Delton, A. W., Robertson, T. E., Simpson, J. A., et al. (2013). When the economy falters, do people spend or save? Responses to resource scarcity depend on childhood environments. Psychological Science, 24(2), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612451471

Guendelman, M. D., Cheryan, S., & Monin, B. (2011). Fitting in but getting fat: Identity threat and dietary choices among U.S. immigrant groups. Psychological Science, 22(7), 959–967. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611411585

Haushofer, J., & Fehr, E. (2014). On the psychology of poverty. Science, 344(6186), 862–867. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1232491

Hill, S. E., Prokosch, M. L., DelPriore, D. J., Griskevicius, V., & Kramer, A. (2016). Low childhood socioeconomic status promotes eating in the absence of energy need. Psychological Science, 27(3), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615621901

Hill, S. E., Rodeheffer, C. D., DelPriore, D. J., & Butterfield, M. E. (2013). Ecological contingencies in women’s calorie regulation psychology: A life history approach. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(5), 888–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2013.03.016

Johnson, S. E., Richeson, J. A., & Finkel, E. J. (2011). Middle class and marginal? Socioeconomic status, stigma, and self-regulation at an elite university. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(5), 838–852. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021956

Johnston, J., Rodney, A., & Szabo, M. (2012). Place, ethics, and everyday eating: A tale of two neighborhoods. Sociology, 46(6), 1091–1108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511435060

Kim, H., Callan, M. J., Gheorghiu, A. I., & Matthews, W. J. (2016). Social comparison, personal relative deprivation, and materialism. British Journal of Social Psychology, 56(2), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12176

Kim, H., Callan, M. J., Gheorghiu, A. I., & Skylark, W. J. (2018). Social comparison processes in the experience of personal relative deprivation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(9), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12531

Kraus, M. W., & Park, J. W. (2014). The undervalued self: Social class and self-evaluation. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01404

Kraus, M. W., Park, J. W., & Tan, J. J. X. (2017). Signs of social class: The experience of economic inequality in everyday life. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(3), 422–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616673192

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., & Keltner, D. (2011). Social class as culture: The convergence of resources and rank in the social realm. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 246–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411414654

Kraus, M. W., Tan, J. J. X., & Tannenbaum, M. B. (2013). The social ladder: A rank-based perspective on social class. Psychological Inquiry, 24(2), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2013.778803

Laran, J., & Salerno, A. (2013). Life-history strategy, food choice, and caloric consumption. Psychological Science, 24(2), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612450033

Layte, R., & Whelan, C. (2014). Who feels inferior? A test of the status anxiety hypothesis of social inequalities in health. European Sociological Review, 30, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu057

Lee, J., & Shrum, L. J. (2012). Conspicuous consumption versus charitable behavior in response to social exclusion: A differential needs explanation. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(3), 530–544. https://doi.org/10.1086/664039

Levy, D. J., & Glimcher, P. W. (2012). The root of all value: A neural common currency for choice. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 22(6), 1027–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2012.06.001

Loughnan, S., Kuppens, P., Allik, J., Balazs, K., de Lemus, S., Dumont, K., et al. (2011). Economic inequality is linked to biased self-perception. Psychological Science, 22(10), 1254–1258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611403

Lynn, M. (1989). Scarcity effects on desirability: Mediated by assumed expensiveness? Journal of Economic Psychology, 10(2), 257–274. Retrieved from http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articleshttp://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles/178

Markus, H. R., & Stephens, N. M. (2017). Inequality and social class: The psychological and behavioral consequences of inequality and social class: A theoretical integration. Current Opinion in Psychology, 18, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.11.001

Mazzocco, P. J., Rucker, D. D., Galinsky, A. D., & Anderson, E. T. (2012). Direct and vicarious conspicuous consumption: Identification with low-status groups increases the desire for high-status goods. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(4), 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2012.07.002

Mead, N. L., Baumeister, R. F., Stillman, T. F., Rawn, C. D., & Vohs, K. D. (2011). Social exclusion causes people to spend and consume strategically in the service of affiliation. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(5), 902–919. https://doi.org/10.1086/656667

Mendes, W. B., Blascovich, J., Major, B., & Seery, M. (2001). Challenge and threat responses during downward and upward social comparisons. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(5), 477–497. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.80

Moore, C. J., & Cunningham, S. a. (2012). Social position, psychological stress, and obesity: A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 112(4), 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2011.12.001

Nettle, D., Andrews, C., & Bateson, M. (2017). Food insecurity as a driver of obesity in humans: The insurance hypothesis. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40, 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X16000947

Offer, A., Pechey, R., & Ulijaszek, S. (2010). Obesity under affluence varies by welfare regimes: The effect of fast food, insecurity, and inequality. Economics and Human Biology, 8(3), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2010.07.002

Oude Groeniger, J., van Lenthe, F. J., Beenackers, M. A., & Kamphuis, C. B. M. (2017). Does social distinction contribute to socioeconomic inequalities in diet: The case of “superfoods” consumption. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0495-x

Oyserman, D., Fryberg, S. A., & Yoder, N. (2007). Identity-based motivation and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1011

Oyserman, D., Smith, G. C., & Elmore, K. (2014). Identity-based motivation: Implications for health and health disparities. Journal of Social Issues, 70(2), 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12056

Paál, T., Carpenter, T., & Nettle, D. (2015). Childhood socioeconomic deprivation, but not current mood, is associated with behavioral disinhibition in adults. PeerJ, 3(e964), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.964

Pickett, K. E., Kelly, S., Brunner, E., Lobstein, T., & Wilkinson, R. G. (2005). Wider income gaps, wider waistbands? An ecological study of obesity and income inequality. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(8), 670–674. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028795

Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., & Keltner, D. (2018). Unpacking the inequality paradox: The psychological roots of inequality and social class. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 57, 53–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2017.10.002

Piketty, T., Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2018). Distributional national accounts: Methods and estimates for the United States. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(2), 553–609. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx043.Advance

Powell, L. M., & Chaloupka, F. J. (2009). Food prices and obesity: Evidence and policy implications for taxes and subsidies. The Milbank Quarterly, 87(1), 229–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00554.x

Rosmond, R., Dallman, M. F., & Bjorntorp, P. (1998). Stress-related cortisol secretion in men: Relationships with abdominal obesity and endocrine, metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 83(6), 1853–1859. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.83.6.1853

Roux, C., Goldsmith, K., & Bonezzi, A. (2015). On the psychology of scarcity: When reminders of resource scarcity promote selfish (and generous) behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(4), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv048

Sánchez-Rodríguez, Á., Willis, G. B., & Rodríguez-Bailón, R. (2017). Economic and social distance: Perceived income inequality negatively predicts an interdependent self-construal. International Journal of Psychology, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12437

Sato, P. M., Gittelsohn, J., Unsain, R. F., Roble, O. J., & Scagliusi, F. B. (2016). The use of Pierre Bourdieu’s distinction concepts in scientific articles studying food and eating: A narrative review. Appetite, 96, 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.010

Schwabe, L., & Wolf, O. T. (2009). Stress prompts habit behavior in humans. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29(22), 7191–7198. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0979-09.2009

Shah, A., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2012). Some consequences of having too little. Science, 338, 682–685. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1222426

Sharma, E., & Alter, A. L. (2012). Financial deprivation prompts consumers to seek scarce goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(3), 545–560. https://doi.org/10.1086/664038

Sim, A. Y., Lim, E. X., Forde, C. G., & Cheon, B. K. (2018). Personal relative deprivation increases self-selected portion sizes and food intake. Appetite, 121, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.100

Sim, A. Y., Lim, E. X., Leow, M. K., & Cheon, B. K. (2018). Low subjective socioeconomic status stimulates orexigenic hormone ghrelin – A randomised trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 89, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.01.006

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1359–1366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417632

Sommet, N., Morselli, D., & Spini, D. (2018). Income inequality affects the psychological health only for people facing scarcity. Psychological Science, 29(12), 1911–1921. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618798620

Spears, D. (2011). Economic decision-making in poverty depletes behavioral control. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy, 11(1), 1935–1682. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1682.2973

Stead, M., McDermott, L., MacKintosh, A. M., & Adamson, A. (2011). Why healthy eating is bad for young people’s health: Identity, belonging and food. Social Science and Medicine, 72(7), 1131–1139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.029

Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R., & Fryberg, S. A. (2012). Social class disparities in health and education: Reducing inequality by applying a sociocultural self model of behavior. Psychological Review, 119(4), 723–744. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029028

Stephen & Townsend (2013): Stephens, N. M., & Townsend, S. S. M. (2013). Rank is not enough: Why we need a sociocultural perspective to understand social class. Psychological Inquiry, 24(2), 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2013.795099

Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R., & Townsend, S. S. M. (2007). Choice as an act of meaning: The case of social class. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 814–830. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.814

Su, D., Esqueda, O. A., Li, L., & Pagán, J. A. (2012). Income inequality and obesity prevalence among OECD countries. Journal of Biosocial Science, 44(4), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002193201100071X

Subramanian, S. V., & Kawachi, I. (2004). Income inequality and health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiologic Reviews, 26, 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxh003

Swaffield, J., & Roberts, S. C. (2015). Exposure to cues of harsh or safe environmental conditions alters food preferences. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 1(2), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-014-0007-z

Sweet, E. (2011). Symbolic capital, consumption, and health inequality. American Journal of Public Health, 101(2), 260–264. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.193896

Tang, D. W., Fellows, L. K., & Dagher, A. (2014). Behavioral and neural valuation of foods is driven by implicit knowledge of caloric content. Psychological Science, 25(12), 2168–2176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614552081

Tirado, L. (2014). Poor people don’t plan long-term. We’ll just get our hearts broken. In The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/sep/21/linda-tirado-poverty-hand-to-mouth-extract

Tomiyama, A. J., Dallman, M. F., & Epel, E. S. (2011). Comfort food is comforting to those most stressed: Evidence of the chronic stress response network in high stress women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(10), 1513–1519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.04.005

van der Veen, M. (2003). When is food a luxury? World Archaeology, 34(3), 405–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/0043824021000026422

Vartanian, L. R., & Porter, A. M. (2016). Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite, 102, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.034

Vartanian, L. R., Spanos, S., Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (2015). Modeling of food intake: A meta-analytic review. Social Influence, 10(3), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2015.1008037

Veblen, T. (1899). The theory of the leisure class: An economic study in the evolution of institutions. New York: Macmillan.

Warde, A. (1994). Consumption, identity-formation and uncertainty. Sociology, 28(4), 877–898. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038594028004005

White, K., & Dahl, D. (2006). To be or not be? The influence of dissociative reference groups on consumer preferences. Advances in Consumer Research, 7, 314–316. 43008804

WHO. (2017a). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/

WHO. (2017b). Obesity and overweight. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2009). Income inequality and social dysfunction. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 493–511. https://doi.org/10.1146/ammrev-soc-070308-115926

Wills, W., Backett-Milburn, K., Roberts, M.-L., & Lawton, J. (2011). The framing of social class distinctions through family food and eating practices. The Sociological Review, 59(4), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2011.02035.x

Woolley, K., & Fishbach, A. (2016). A recipe for friendship: Similar food consumption promotes trust and cooperation. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2016.06.003

Zucman (2018): Alvaredo, F., Atkinson, A., Piketty, T., Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2017). The World Wealth and Income Database. Retrieved from: http://WID.world.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Claassen, M.A., Corneille, O., Klein, O. (2019). Psychological Consequences of Inequality for Food Intake. In: Jetten, J., Peters, K. (eds) The Social Psychology of Inequality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28856-3_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28856-3_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-28855-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-28856-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)