Abstract

Delirium is one of the most common manifestations of acute brain dysfunction. It is a serious complication in people receiving care throughout the hospital and a strong predictor of worse outcomes. Despite its high prevalence, delirium goes undetected without the use of a structured tool in up to three out of four patients by bedside nurses and medical practitioners in many hospital settings. Delirium monitoring with a valid and reliable tool is recommended in numerous guidelines as part of routine clinical care, and multiple tools have been developed for reliable monitoring in ICU and non-ICU settings. Regular monitoring of delirium allows its enhanced detection that could facilitate clinical management and improve patient outcomes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Delirium is the most common manifestation of acute brain dysfunction and is increasingly understood as a serious medical event during hospitalization. It is most commonly precipitated by underlying medical conditions, iatrogenic causes (e.g., administration of deliriogenic medications), sensory impairment (e.g., removal of eye glasses or hearing aids), immobilization, and alterations of sleep cycle. It is a prevalent complication in people receiving care throughout the hospital, especially in older people, those with dementia, and patients admitted to intensive care, postoperative, geriatric, and palliative care units [1, 2]. Delirium during the ICU period is a strong predictor of increased length of mechanical ventilation, longer ICU and hospital stays, increased risk of falls, increased health care cost, mortality [3,4,5,6,7], and is linked to negative outcomes long after hospital discharge such as increased mortality and cognitive impairment [4, 8, 9]. The first step in managing ICU delirium is systematic monitoring with a validated delirium assessment tool. Current recommendations focus on valid assessment of pain, sedation, and delirium in tandem [10, 11]. This highlights the fundamental interconnectedness of delirium and other patient symptoms and interventions in the ICU. Delirium assessment is so fundamental to critical care management that it is now a core feature in the evidence-based organizational approach referred to as the “ABCDEF bundle” (awakening and breathing coordination, choice of sedatives, delirium monitoring, early mobility, and family engagement and empowerment) [10,11,12,13,14]. Currently, there are enormous variations in practice, with most patients not routinely monitored for delirium in hospital wards and ICUs around the world and with most delirium going undiagnosed [15].

This chapter describes the most common delirium assessment tools for the ICU and outlines how to use those tools to inform delirium prevention and management strategies.

Definition of Delirium

Delirium is an acute neuropsychiatric disorder that is characterized by a loss of attention and accompanied by cognitive change, perceptual disturbance, and/or change in level of consciousness (LOC). Delirium first appeared in medical writings over 2000 years ago [16], and today the term is widely used in medicine and in everyday language and pop culture. There are bands, movies, and beers that bear the name. As a result, there is widespread variation in defining the term [17]. In this era that demands ICU clinicians to practice in multiprofessional teams, it is important that each team member uses medical terms accurately and consistently in order to maximize the care and treatment for patients and families. The primary source for defining delirium has become the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM details explicit diagnostic criteria for delirium and thus serves as the reference standard (see previous chapter for further details). The most recent revision, the DSM-5, outlines the core criteria for delirium providing more detailed descriptions of each feature and differentiates it from severe neurocognitive disorders and coma [18]. According to DSM-5 criteria, delirium is defined as an acutely developing deficit in attention (reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention) coupled with a change in cognition (memory deficit, disorientation, or perceptual disturbance) [18]. While no major criteria were changed in the revision, it did include some minor changes that prompted some to criticize that the new criteria could be interpreted too narrowly [19]. Meagher and colleagues compared the DSM-IV and two versions of the DSM-5, a strict version (all DSM-5 criteria in their most explicit forms) and a relaxed version (delirium features in all possible forms) with more general interpretation of the criteria. The strict application of DSM-5 criteria interpretation excluded cases with substantial delirium symptoms, but the relaxed version included these patients, thus leading the authors to recommend the relaxed interpretation [19]. The European Delirium Association and the American Delirium Society both endorse a relaxed approach to the criteria interpretation [20]. This debate underscores that, while the DSM-5 provided more detailed explanations of the delirium criteria, it still requires psychiatric training to navigate and interpret. This complexity does not lend itself to widespread application; thus, valid and reliable assessment tools are needed for general bedside practitioners.

Delirium Assessment Tools for the ICU

Despite the high prevalence of delirium, delirium goes undetected by bedside nurses and medical practitioners in up to three out of four patients when structured assessment tools are not used [27,28,23]. This is, in part, because symptoms of delirium are often “quiet” (hypoactive rather than hyperactive), challenging to recognize in patients who are sedated or nonverbal [30,31,32,27], and frequently fluctuate during the day. Bedside critical care clinicians need delirium assessment tools that, while validated against the DSM standards, are easy to use, are easy to communicate, and have good inter-rater reliability. While many tools have been developed over time, they do not all have strong psychometric properties. In 2013, the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium (PAD) in Adult Patients in the ICU evaluated a myriad of ICU delirium assessment tools and identified two tools satisfying the threshold for recommendation: Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) [28, 29] and Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) [30]. Gelinas and colleagues reproduced the PAD guideline psychometric evaluation using updated data and again concluded only the CAM-ICU and ICDSC met the acceptable threshold for delirium monitoring [31]. Other tools evaluated for psychometric and feasibility properties that did not meet the acceptable threshold include the Cognitive Test for Delirium, the Delirium Detection Score, and the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale. In 2018, the updated version of the guidelines confirmed the role of validated screening tools, including CAM-ICU and ICDSC to improve delirium recognition [10].

There are a variety of other tools developed for use outside the ICU (e.g., Confusion Assessment Method [CAM], 4 A’s Test [4AT] [32], Nursing Delirium Screening Scale [Nu-DESC] [33], Delirium Observation Screening Scale [34], Single Question in Delirium [SQiD] [35], Recognizing Acute Delirium As part of your Routine [RADAR] [36]). However, this chapter focuses on tools developed and validated for use in critically ill patients. The following sections provide an overview of the two guideline-recommended and validated ICU delirium monitoring tools.

CAM-ICU

The CAM-ICU scale (Fig. 2.1a) was designed as an adaptation of the original CAM [37] in order to evaluate delirium objectively in a largely nonverbal population due to mechanical ventilation [28, 29]. It is a point-in-time assessment tool. The CAM-ICU evaluates for delirium by assessing four diagnostic features: (1) sudden changes/fluctuations in mental status, (2) inattention, (3) altered levels of consciousness, and (4) disorganized thinking. The patient is considered CAM-ICU positive (i.e., delirious) if he/she manifests both features 1 and 2, plus either feature 3 or 4. The original CAM-ICU validation study was conducted with 111 patients being evaluated by two independent observers. The observer CAM-ICU evaluations were compared with an assessment conducted by a psychiatrist employing the DSM-IV criteria for delirium diagnosis. Analysis revealed a specificity of 93% and 100% for both raters, respectively, and a sensitivity of 98% and 100% for both raters, respectively [28]. Further studies have demonstrated the usefulness of the CAM-ICU in routine clinical assessment of delirium in ICU patients in other critical care environments to include surgery, trauma, burn, cardiovascular, and neurological ICU settings [38]. A meta-analysis performed by Gusmao-Flores et al. demonstrated excellent accuracy of the CAM-ICU with pooled sensitivity of 80% (95% confidence intervals (CI): 77.1–82.6%) and specificity of 95.9% (95% CI: 94.8–96.8%) for detecting delirium [39]. Evaluation of CAM-ICU features is conducted through objective evaluation. The CAM-ICU has been translated in over 30 languages which can be found at www.icudelirium.org/cibs-center along with training materials and videos.

There is one recent adaptation of the CAM-ICU to highlight [10]. The CAM-ICU-7 is a severity rating scale based on the CAM-ICU assessment. Specific points are assigned for each feature. The CAM-ICU-7 scores are categorized as 0–2, no delirium; 3–5, mild to moderate delirium; and 6–7, severe delirium [40] (Table 2.1). A recent observational study using the CAM-ICU-7 suggests an association between delirium severity and worse outcomes (i.e., ICU and hospital length of stay and the probability of returning home) [40].

ICDSC

Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) is an 8-item checklist (Fig. 2.1b) validated in 2001 by Bergeron et al. [30]. The ICDSC incorporates both a point-of-care focused evaluation by the bedside clinician and evaluation of other delirium features manifesting during the remainder of a specified time period (e.g., 12-h nursing shift). The eight predefined diagnostic criteria as per DSM-IV include altered LOC, inattention, disorientation, hallucination or delusion, changes in psychomotor activity (agitation and retardation), inappropriate mood or speech, sleep/wake cycle disturbances, and symptom fluctuation [30]. Patients are given one point for each delirium symptom manifesting over the course of a shift. The ICDSC is positive for delirium when at least four out of eight criteria are present. The validation study performed by Bergeron et al. compared ICDSC to a psychiatric evaluation and reported sensitivity of 99% and specificity of 64% in detecting ICU delirium. According to the meta-analysis by Gusmao-Flores et al., the ICDSC has good accuracy (area under ROC 0.89) with pooled sensitivity of 74% (95% CI: 65.3–81.5%) and pooled specificity of 81.9% (95% CI: 76.7–86.4%) [39].

Incorporating Delirium Assessment into Clinical Practice

Regular monitoring of delirium with a valid and reliable tool allows for enhanced detection of delirium and facilitates a coherent clinical plan in which specific management of the patient’s delirium is planned alongside other aspects of care, thus coordinating care and optimizing therapeutic interventions [47,48,49,50,51,46]. Moreover, delirium monitoring can reveal early signs of acute and serious physiologic problems (e.g., acute disruption to homeostasis, adverse drug effects, organ dysfunction) and stimulate rapid and responsive medical care. Routine delirium monitoring can help overcome delirium miscommunications between the multidisciplinary team [47] and improve precision of diagnostic understanding and language. This enhanced communication is achieved by counteracting the numerous misnomers for delirium (ICU psychosis , confusion, and terminal agitation ) which downplay the significance and severity of delirium and contribute to its under-recognition, poor assessment, and inadequate follow-up care [48].

Assessment Recommendations

Delirium assessment should be performed serially in order to obtain the best picture of the patient’s mental status. Delirium assessment can be performed by any healthcare professional, although nurses most commonly perform the assessment and should be included as part of standard care. The role of nurses in this process is critically important due to the nurse’s consistent close patient contact and interaction. Since a key feature of delirium is fluctuation, the guidelines recommend delirium evaluation be performed at least every shift (e.g., every 8 or 12 h) and each time a change in mental status is noted [10, 49]. Delirium assessment can most often be completed in <1 min. The result of delirium assessments should be recorded in patient medical record documents to enable its use for members of the multidisciplinary team.

The assessment of delirium is an important element of general assessment of the state of consciousness and is conducted in two stages. The first step is to assess the LOC, via either the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) (see previous chapter for figure) or Sedation Agitation Scale (SAS) (Fig. 2.2). The next step is to assess the content of consciousness (i.e., delirium). In cases of coma (e.g., RASS −4, RASS −5 or SAS 1, SAS 2), it is impossible to assess for delirium because the patient is unresponsive to external stimuli. Coma disqualifies the patient from delirium evaluation. However, a patient can be assessed for delirium if there is any responsiveness to verbal stimulation (e.g., RASS −3 to +4 or SAS 3–7). When it is possible to obtain at least the beginnings of meaningful reactions (e.g., any response to voice), the content of consciousness should be evaluated, and delirium can be assessed.

Sedation Agitation Scale (SAS). Guidelines for SAS Assessment: (1) agitated patients are scored by their most severe degree of agitation as described. (2) If patient is awake or awakens easily to voice (“awaken” means responds with voice or head shaking to a question or follows commands), that’s a SAS 4 (same as calm and appropriate – might even be napping). (3) If more stimuli such as shaking are required but patient eventually does awaken, that’s SAS 3. (4) If patient arouses to stronger physical stimuli (may be noxious) but never awakens to the point of responding yes/no or following commands, that’s a SAS 2. (5) Little or no response to noxious physical stimuli represents a SAS 1. This helps separate sedated patients into those you can eventually wake up (SAS 3), those you can’t awaken but can arouse (SAS 2), and those you can’t arouse (SAS 1)

Implementation Recommendations

Implementation of routine delirium monitoring requires not only appropriate practical training (e.g., expert lectures, workshops, case-based scenarios, visual aids, mnemonics, bedside teaching) in the ICU environment but also institutional support and acknowledgment of the necessity for delirium screening [50]. Implementation trials have shown that great importance must be put on follow-up teaching, reinforcement, and audits of delirium screening in order to maintain high levels of compliance and reliability many years after implementation [51].

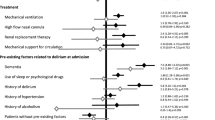

A “delirium vigilance approach” can enhance implementation success by employing altered LOC as a trigger to perform delirium assessment [52], brain roadmaps for multiprofessional communication, mnemonics for risk identification, and structured documentation systems for quality improvement performance tracking [20, 47]. Clinical dashboards can trigger delirium assessment if a patient’s LOC meets criteria for delirium assessment (i.e., RASS −3 to +4, SAS 3–7) but delirium status has not been documented. The brain roadmap (Fig. 2.3) provides the script for communicating delirium assessment results in addition to relevant information to guide delirium management discussion during interdisciplinary rounds. Components of the brain roadmap communication framework are pain assessment, target and actual LOC, delirium assessment, and sedative/analgesic/antipsychotic medications received in the previous 24 h [50]. Mnemonics (Table 2.2) [e.g., Dr. DRE, THINK, DELIRIUM(S)] can then be applied to guide discussion of predisposing and precipitating factors contributing to delirium and, thus, determine a patient-centered therapeutic management approach. Finally, quality improvement feedback can be created using data from the medical record. Structured delirium documentation and recording delirium components in addition to only the overall assessment result can provide data for tracking process and outcome measures for quality improvement initiatives to reduce delirium prevalence in addition to monitoring assessment reliability.

The brain roadmap for rounds. (Adapted from www.icudelirium.org)

Interprofessional Approach to Delirium Management

The PAD-IS guidelines recommend using a multidisciplinary ICU team approach to facilitate pain, agitation, and delirium management [10, 49]. The ABCDEF bundle, a group of evidence-based critical care practices, provides a framework for implementation of this recommendation. This bundle emphasizes essential routine patient assessments (i.e., pain, LOC, delirium) and prioritizes key interventions (e.g., sedation cessation, spontaneous breathing trials, early mobility). Implementation of the ABCDEF bundle maximizes the likelihood of successful patient engagement in each individual bundle component. Outcomes associated with ABCDEF bundle implementation include reduced duration of delirium and mechanical ventilation and a higher likelihood of early mobilization and hospital survival [11,12,13,14].

Conclusion

Delirium monitoring should become part of routine clinical care for every ICU patient. Validated simple and quick assessment tools are available for routine use by non-psychiatric personnel. The choice of which validated delirium assessment tool and implementation process to use is dependent on patient needs, goals of care, and organizational structure. Regular monitoring of delirium allows an enhanced detection of delirium that could facilitate the clinical management of the patient leading to improved patient outcomes and increased awareness of early signs of acute and serious physiological problems, thus stimulating rapid and responsive medical care.

References

Ryan DJ, O’Regan NA, Caoimh RÓ, Clare J, O’Connor M, Leonard M, et al. Delirium in an adult acute hospital population: predictors, prevalence and detection. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001772.

Hosie A, Davidson PM, Agar M, Sanderson CR, Phillips J. Delirium prevalence, incidence, and implications for screening in specialist palliative care inpatient settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013;27(6):486–98.

Ely EW, Baker AM, Dunagan DP, Burke HL, Smith AC, Kelly PT, et al. Effect on the duration of mechanical ventilation of identifying patients capable of breathing spontaneously. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(25):1864–9.

Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, Speroff T, Gordon SM, Harrell FE Jr, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753–62.

Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB, Nagaraja N, Yenokyan G, Damluji A, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h2538.

Klein Klouwenberg PMC, Zaal IJ, Spitoni C, Ong DSY, van der Kooi AW, Bonten MJM, et al. The attributable mortality of delirium in critically ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6652.

Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27–32.

Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1306–16.

Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, Ely EW. Duration of delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:A5477.

Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gelinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(9):e825–e73.

Barnes-Daly M, Phillips G, Ely E. Improving hospital survival and reducing brain dysfunction at 7 California community hospitals: implementing PAD guidelines via the ABCDEF bundle in 6,064 patients. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):171–8.

Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Olsen KM, Schmid KK, Shostrom V, Cohen MZ, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(5):1024–36.

Ely EW. The ABCDEF bundle: science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):321–30.

Barnes-Daly MA, Pun BT, Harmon LA, Byrum DG, Kumar VK, Devlin JW, et al. Improving health care for critically ill patients using an evidence-based collaborative approach to ABCDEF bundle dissemination and implementation. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2018;15(3):206–16.

Morandi A, Piva S, Ely EW, Myatra SN, Salluh JIF, Amare D, et al. Worldwide survey of the “assessing pain, both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, choice of drugs, delirium monitoring/management, early exercise/mobility, and family empowerment” (ABCDEF) bundle. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:e1111–22.

Deksnyte A, Aranauskas R, Budrys V, Kasiulevicius V, Sapoka V. Delirium: its historical evolution and current interpretation. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(6):483–6.

Morandi A, Pandharipande P, Trabucchi M, Rozzini R, Mistraletti G, Trompeo AC, et al. Understanding international differences in terminology for delirium and other types of acute brain dysfunction in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(10):1907–15.

Association. AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Meagher DJ, Morandi A, Inouye SK, Ely W, Adamis D, Maclullich AJ, et al. Concordance between DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria for delirium diagnosis in a pooled database of 768 prospectively evaluated patients using the delirium rating scale-revised-98. BMC Med. 2014;12:164.

European Delirium A, American Delirium S. The DSM-5 criteria, level of arousal and delirium diagnosis: inclusiveness is safer. BMC Med. 2014;12:141.

Devlin JW, Fong JJ, Schumaker G, O’Connor H, Ruthazer R, Garpestad E. Use of a validated delirium assessment tool improves the ability of physicians to identify delirium in medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(12):2721–4.

Han JH, Eden S, Shintani A, Morandi A, Schnelle J, Dittus RS, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients is an independent predictor of hospital length of stay. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(5):451–7.

Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, Katz KH, Cooney LM Jr. Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(20):2467–73.

Patel SB, Kress JP. Accurate identification of delirium in the ICU: problems with translating the evidence in the real-life setting. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(3):287–8.

Spronk PE, Riekerk B, Hofhuis J, Rommes JH. Occurrence of delirium is severely underestimated in the ICU during daily care. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(7):1276–80.

Devlin JW, Fong JJ, Howard EP, Skrobik Y, McCoy N, Yasuda C, et al. Assessment of delirium in the intensive care unit: nursing practices and perceptions. Am J Crit Care. 2008;17(6):555–65.. quiz 66

Pun BT, Devlin JW. Delirium monitoring in the ICU: strategies for initiating and sustaining screening efforts. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34(2):179–88.

Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Dittus R, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1370–9.

Ely EW, Inouye SK, Bernard GR, Gordon S, Francis J, May L, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). JAMA. 2001;286(21):2703–10.

Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Skrobik Y. Intensive care delirium screening checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(5):859–64.

Gelinas C, Berube M, Chevrier A, Pun BT, Ely EW, Skrobik Y, et al. Delirium assessment tools for use in critically ill adults: a psychometric analysis and systematic review. Crit Care Nurse. 2018;38(1):38–49.

McLullich A. The 4AT – a rapid assessment test for delirium 2014. Available from: http://www.the4at.com/.

Gaudreau JD, Gagnon P, Harel F, Tremblay A, Roy MA. Fast, systematic, and continuous delirium assessment in hospitalized patients: the nursing delirium screening scale. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;29(4):368–75.

Schuurmans MJ, Shortridge-Baggett LM, Duursma SA. The delirium observation screening scale: a screening instrument for delirium. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2003;17(1):31–50.

Sands MB, Dantoc BP, Hartshorn A, Ryan CJ, Lujic S. Single Question in Delirium (SQiD): testing its efficacy against psychiatrist interview, the confusion assessment method and the memorial delirium assessment scale. Palliat Med. 2010;26(6):561–5.

Voyer P, Champoux N, Desrosiers J, Landreville P, McCusker J, Monette J, et al. Recognizing acute delirium as part of your routine [RADAR]: a validation study. BMC Nurs. 2015;14:19.

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–8.

Soja SL, Pandharipande PP, Fleming SB, Cotton BA, Miller LR, Weaver SG, et al. Implementation, reliability testing, and compliance monitoring of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit in trauma patients. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(7):1263–8.

Gusmao-Flores D, Salluh JI, Chalhub RA, Quarantini LC. The Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) and Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) for the diagnosis of delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Crit Care. 2012;16(4):R115.

Khan BA, Perkins AJ, Gao S, Hui SL, Campbell NL, Farber MO, et al. The confusion assessment method for the ICU-7 delirium severity scale: a novel delirium severity instrument for use in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(5):851–7.

Hshieh TT, Yue J, Oh E, Puelle M, Dowal S, Travison T, et al. Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):512–20.

Lakatos BE, Capasso V, Mitchell MT, Kilroy SM, Lussier-Cushing M, Sumner L, et al. Falls in the general hospital: association with delirium, advanced age, and specific surgical procedures. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3):218–26.

Mudge AM, Maussen C, Duncan J, Denaro CP. Improving quality of delirium care in a general medical service with established interdisciplinary care: a controlled trial. Intern Med J. 2013;43(3):270–7.

van den BM, Pickkers P, van der HH, Roodbol G, van AT, Schoonhoven L. Implementation of a delirium assessment tool in the ICU can influence haloperidol use. Crit Care. 2009;13(4):R131.

Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911–22.

Luetz A, Weiss B, Boettcher S, Burmeister J, Wernecke KD, Spies C. Routine delirium monitoring is independently associated with a reduction of hospital mortality in critically ill surgical patients: a prospective, observational cohort study. J Crit Care. 2016;35:168–73.

Brummel NE, Vasilevskis EE, Han JH, Boehm L, Pun BT, Ely EW. Implementing delirium screening in the intensive care unit: secrets to success. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9):2196.

Morandi A, Solberg LM, Habermann R, Cleeton P, Peterson E, Ely EW, et al. Documentation and management of words associated with delirium among elderly patients in postacute care: a pilot investigation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(5):330–4.

Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gelinas C, Dasta JF, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263–306.

Brummel NE, Vasilevskis EE, Han JH, Boehm L, Pun BT, Ely EW. Implementing delirium screening in the ICU: secrets to success. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(9):2196–208.

Vasilevskis EE, Morandi A, Boehm L, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Delirium and sedation recognition using validated instruments: reliability of bedside intensive care unit nursing assessments from 2007 to 2010. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(Suppl 2):S249–55.

Chester JG, Beth Harrington M, Rudolph JL, Group VADW. Serial administration of a modified Richmond agitation and sedation scale for delirium screening. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):450–3.

Ely EW, et al. Delirium in mechanically ventilated patients: validity and reliability of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2003;289:2983–91.

Sessler CN, Gosnell M, Grap MJ, Brophy GT, O’Neal PV, Keane KA, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1338–44.

Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JWW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: the reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA. 2003;289:2983–91.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Marra, A., Boehm, L.M., Kotfis, K., Pun, B.T. (2020). Monitoring for Delirium in Critically Ill Adults. In: Hughes, C., Pandharipande, P., Ely, E. (eds) Delirium. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25751-4_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25751-4_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-25750-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-25751-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)