Abstract

This chapter intends to give an overview regarding the historical and recent developments in adult education research in Germany, looking back over more than 100 years. At first, the research was undertaken by the adult educators themselves, who wanted to know more about the practice of adult education, the participants and the conditions under which adult education should ideally be provided and taught. As a result of the scientific expansion in the 1970s, a pluralistic and diverse research landscape has emerged using a wide variety of methodological approaches and theoretical frameworks, resulting in a fragmented field.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This chapter intends to give an overview regarding the historical and recent developments in adult education research in Germany, looking back over more than 100 years. At first, the research was undertaken by the adult educators themselves, who wanted to know more about the practice of adult education, the participants and the conditions under which adult education should ideally be provided and taught. As a result of the scientific expansion in the 1970s, a pluralistic and diverse research landscape has emerged using a wide variety of methodological approaches and theoretical frameworks, resulting in a fragmented field.

The aim of adult education has always been to provide opportunities for adults to learn – for individual intellectual, cultural or political development, for career advancement and, regarding society, for political and social change. The conflicts of interest and objectives, which are related to the diverse individual and collective points of view, are reflected in the debates concerning adult education. However, the relationship between adult education practice and theory has always been close, because they are mutually dependent. Adult education practice provides the field for theory and research and asks questions concerning improvements in practice. Nevertheless, the relationship between theory and practice could also be ambivalent, because neither side is sure of what to expect and how to gain from each other. Experience has shown that the results from theory and research are not easily transferred into practice, but often need adjustments.

In order to explain the current state of adult education research in Germany, the first part of the chapter addresses the question of how underlying theoretical frameworks influence research. I will discuss whether they are only relevant to the theoretical perspective of the researcher or whether they influence the research itself and to what means and outcomes.

The second part of the chapter argues for the concept of ‘Bildung’ as the aim of adult education. Over the last 20 years, this notion has been overshadowed by aspects such as learning or acquiring competences, being considered the main objective of adult education. Whereas the first notion looks at the personal development and enrichment of subjects in order for them to lead fulfilled lives according to their abilities and aspirations, learning and acquiring competences are rather aimed at fulfilling external expectations. This seems to have influenced both the research questions and the research methods.

Following these introductory remarks, I will then look at the historical development of adult education research in Germany and its current state. The presentation of the historical developments will focus on the main topics and on the methodological approaches and concepts. They indicate a continuum of research questions, as well as an expansion of the methodological designs.

I will write the article from a critical-theoretical-pragmatistic point of view in order to stress the fact that this perspective on adult education research abandons the illusion that individual learning or education processes can be induced from ‘from the outside’. It thus exceeds an instrumental interest in knowledge and combines it with hermeneutic or practical research intentions. In this way, it creates a break with an object’s immediacy and becomes critical empiricism. Because the results of research are related to the interpretations and points of view of the researchers, they are not fixed. Therefore, this article on adult education research in Germany cannot provide thorough lexical knowledge. It rather aims at giving an overview of the research questions and topics, the methodological approaches, the discussions and the experiences which open up new horizons. Empirical research – both as historical-genetic and as methodological-experience-led access to a subject area – can be seen as a learning process in which the apparently self-evident becomes uncertain, and new answers are sought (Zeuner and Faulstich 2009, p. 11).

2 Adult Education Research in Germany: Theoretical Frameworks

Adult education research in Germany is situated in the tradition of social scientific research, on the one hand, and in the tradition of humanistic approaches to pedagogy, on the other hand. Traditionally, adult education research has had a close relationship to adult education practice. Ideally, the practice of adult education provides a field for adult education research to develop topics and questions, with the results being fed back into practice.

Until some years ago, the field was built around this common ground, albeit sometimes rather ambivalently, i.e. on the reciprocal relationship between the field of adult education research and practice. More recently, researchers in adult education have started to contest this view. Due to the increasingly competitive nature of research funding, questions concerning adequate topics and methodological approaches have gained momentum, as well as expectations for so-called ‘evidenced based’ research. These collegial discussions are ongoing, resulting in the effect that adult education research seems to have become an even more fragmented field (Nuissl 2010, p. 406).

Adult education practice presents itself as multi-layered and diverse – in its organised forms ranging from popular and cultural approaches to citizenship education, from basic education to higher education, and from basic vocational training to further vocational training. In addition, different learning-settings have come into view, ranging from autodidactic learning to self-directed learning, to organised and formalised learning, and so on. Adult education, in its multidimensional practice, provides the background and framework for adult education research. Therefore, not surprisingly, the theoretical as well as scientific references of adult education research are similarly pluralistic.

Other disciplines such as educational science, sociology, psychology, economics, history, and economics, to name the most relevant, are often referred to when it comes to defining the methodological approaches or research interests. In addition, researchers from these disciplines also conduct studies in adult education/continuing education, and their results influence the scientific discourse and practice of adult education. Consequently, adult education presents itself as a rather diffuse and fragmented field.

Adult education research draws on a wide range of theoretical approaches, partly corresponding to the dominant theoretical currents which are prevalent in the related disciplines. But even though certain theoretical positions may be favoured at certain times, multiple positions can appear simultaneously. There has been an ongoing debate in German adult education research about the significance of theoretical frameworks for the explanation and development of science and their functions with regard to ‘Bildung’.

A theory is defined as ‘a system of intersubjectively verifiable, methodically obtained and in a consistent context formulated statement about a defined subject area’ (Dewe et al. 1988, p. 15). Theories are the results of science, which is seen as an ‘organized process of understanding natural and/or social realities. The aim of science is to describe and structure closely defined fields as realistically as possible’ (Dewe et al. 1988, p. 14).

Horst Siebert (2011), in his book on adult education theory, focuses on the relationship between theory and practice in order to define the special characteristics of adult education theory. According to Siebert, adult education theories are not basic theories which attempt to describe social reality (or utopias) in their entirety. In relation to professional action in adult education, they rather address partial aspects of the field and make them accessible to reflection: ‘Adult pedagogical theories of medium reach are oriented towards concepts and tasks of institutional educational practice, attempting to explain and discuss problems by means of scientific findings and thus to stimulate and justify educational practice’ (Siebert 2011, p. 18).

The prevalent (philosophical) theoretical positions to which adult education has referred since the Second World War are the following: positivism, symbolic interactionism (referring to the interpretative paradigm), critical theory, social constructivism, and pragmatism. In recent times, the milieu and habitus theory proposed by Pierre Bourdieu has also become more important. In addition, over the last 20 years, psychological learning theories (behaviourism, cognitivism, action regulation theory, subject-oriented learning theory, transformative learning) have been discussed and used as frameworks for research. For most of these theoretical frameworks, it is possible to identify the typical methodological approaches which support and mirror specific research interests (Zeuner and Faulstich 2009, pp. 15–2615ff).

Applied to adult education, each of these theoretical approaches is based on its own understanding of how to determine the role of education in society and the role of the individual. In addition, some of the approaches are based on specific concepts with regard to the socio-theoretical framework (what kind of society is favoured and which role adult education assumes therein), e.g. the anthropological framework (according to which the human image forms the basis of the approach) and the psychological framework (regarding the individual image of the learner).

Looking more closely at the development of adult education research since the 1990s, the role that a researcher accounts to the individual learner has become more and more crucial. Whereas approaches such as critical theory, pragmatism or that of Bourdieu see the individual in relation to and in connection with society, approaches favouring the interpretative paradigm rather look at the individual learner. In the interpretative paradigm, the major interest lies in the lifeworld of individuals, their everyday knowledge and their lifelong learning processes, whereas the perception of the reciprocal effects between the learner and society seems to be rather limited. This kind of research has been criticised as being shortsighted. Aspects influencing the individual learning process such as social background, learning experience, school experience, and so on also need to be considered in order to understand the participation and effects of adult education (Zeuner and Faulstich 2009, p. 21).

Methodologically speaking, adult education research covers a wide range of approaches. Based on the theoretical framework applied, different ones will be used. Typically, it is differentiated between empirical-quantitative or qualitative methods. Quantitative methods are usually employed in large-scale assessments, which is a rather recent approach induced by international policy agencies such as the OECD or the European Union, or by the German government. Qualitative methods rather refer to the interpretative paradigm, within which explorative, biographical and historical approaches, case-studies, ethnography and other methods are used (Dörner and Schäffer 2011, p. 244).

The so-called ‘interpretative paradigm’ is based on the social constitution of the research topic, in which the respondents are regarded as ‘experts of their own life world’. In order to understand this, researchers need to involve themselves in close interactions with their respondents in order to become able to adequately interpret the collected data (Kade 1999, p. 342). I would argue that a clear distinction should be made between the interpretative paradigm of the research and the normative paradigm in the research, which is based on theoretically founded research hypotheses that are verified or falsified by empirical evidence. Followers of the interpretative paradigm reject the idea of hypothesis-guided questions, because in their view, they restrict the possible interpretations and restrict the openness of the research process itself. Therefore, in the interpretative paradigm, the explication and interpretation of data seem to be more flexible and changeable (Kade 1999, p. 342).

Although certain methods have had primacy in adult education research at certain times, they are selected according to the objectives and interests of the research and on the basis of practical considerations, such as time, money, access to the field, etc. Adult education research therefore presents itself as a multifaceted field, ranging from small-scale individual research for qualification purposes, such as a doctoral thesis, to funded research projects and large-scale (often quantitative) research networks (Nuissl 2010, p. 406).

One characteristic of adult education research in Germany has always been a broad scope of orientations, ranging from pure basic research to an applied research orientation. Typical approaches to adult education research are the following:

-

1.

Theoretical research that exists independently of practice (pure basic research).

-

2.

Theoretical research aiming at practical application (use inspired basic research)

-

3.

Scientific research resulting from practical requirements (applied research).

Most of the research on adult education can be assigned to the latter two areas (Zeuner and Faulstich 2009, p. 28). Related to this systematisation, topics of adult education research can be assigned to the following different strands:

-

1.

Discussions on the theoretical foundations of adult education: humanities-hermeneutical, empirical-analytical, critical-theoretical, critical-pragmatistic, constructivist, ecological, interactionist and other approaches.

-

2.

Research on the practice of adult education: teaching and learning; adult education institutions including questions on organisation and structure, staff and personnel, progammes and programme-planning; on participants and addressees; system and structure.

-

3.

The programmatic objectives of adult education: emancipation and democratisation; learning and self-organisation; education politics and policy; economisation.

However, typically, ‘mixed approaches’ are used, i.e., one usually finds neither a solely pure basic research nor a solely applied research. Depending on the objectives of the research and the methods applied, the relationship between theory and practice to which I referred earlier is prevalent and influences the research. However, the topics, themes, research interests and theoretical positions are also subject to the apparent ‘trends’ and are therefore subject to change.

3 ‘Learning’ or ‘Bildung?’ The Aims of Adult Education

The core interests of adult education research and its aims have been widely discussed. Different issues have been prevalent at different times. However, two topics have always been prominent in adult education practice and research. The first concerns the question of whether adult education mainly provides opportunities for learning or whether the overall aim should be ‘Bildung’.

Hans Tietgens (1922–2009), the long-term director of the Institute for Didactic of Adult Education,Footnote 1 stated in 1991 that the main task of adult education should be the initiation of teaching-learning processes. Accordingly, adult education ‘can only be understood as a process, as a product of interaction. Adult education […] only exists, when learning processes take place’ (Tietgens 1991, p. 46).

‘Bildung’ becomes the ultimate objective of adult education when referring to its emancipatory, democratic tradition. ‘Bildung’ has no appropriate English translation, and it emerged from a critical theoretical tradition that ultimately aims at (self-)enlightenment. This involves the development of individual identity, the appropriation of culture and the development of the person, as well as the development of a collective social identity. According to the educational scientist Wolfgang Klafki (1927–2016), education with regard to (self-)enlightenment processes can be defined as follows: ‘self-determination, freedom, emancipation, autonomy, maturity, reason, self-activity’ (Klafki 1996, p. 19). This, for him, includes the ‘freedom of one’s own thinking and one’s own moral decision. It is precisely for this reason that self-activity is the central form of implementation of the educational process’ (Klafki 1996, p. 19, emphasis in the original). From this point of view, Bildung should not only serve the purpose of self-education and individual self-fulfillment, it should also aim at solidarity, cooperation and responsibility in order to become capable of shaping the future of a democratic society.

Regardless of whether the focus of adult education is on learning or Bildung, adult education, as part of the educational system, is always embedded in macro-, meso- and microstructures. They provide the essential framework for learning or Bildung and are therefore the subject of research, justifying the pluralistic field of adult education research. Whereas the macrostructure concerns adult education politics, policy and the law, the mesostructure mostly looks at the institutions and organisation of adult education, including questions concerning the professional action of its protagonists and participation. The microstructure concerns actual learning and teaching processes, and therefore, in the long run, also the question of whether these processes lead to Bildung.

4 Adult Education Research: A Short Historical Overview

The following overview will outline the historical development of adult education research in Germany from its beginnings at the turn of the twentieth century to the turn of the twenty-first century. It indicates a strong tradition of mutual influence between the theory and practice of adult education, and – in the late twentieth century – the attempts of some researchers to prove that adult education research is pure basic research in its own right.

4.1 The Beginnings: 1900–1933

As mentioned earlier, adult education research developed out of the needs of practitioners. One of the first surveys, which concerned participants of extension classes at the University of Vienna was conducted by its secretary, Ludo Moritz Hartmann (Hartmann and Penck 1904). From the beginning of the lectures in 1885, he collected data on significant events and participants. The participants were analysed regarding age, gender and social background. On the one hand, Hartmann used the results of his survey to plan the extension programme according to the motives and interests of the participants. On the other hand, the survey served to legitimise the extension service of the university and was used to ask for public funding. Hartmann’s survey was exemplary, and its structure concerning participant research was later replicated and extended.

Research concerning participants became the first strand of adult education research that German-speaking countries conducted in different institutions and organisations which offered learning opportunities for adults such as adult education centres and public libraries.

During the Weimar Republic (1919–1933), adult education research reached its first peak, mainly due to two developments, the first being an enormous expansion of the practice of adult education. Different types of adult education centres (Volkshochschulen) were founded (Zeuner 2010), and workers’ education institutions were constructed by trade unions and political parties. Churches, farmer movements, as well as universities became interested in adult education and founded their own institutions or offered classes.

The second development was more or less reciprocal: The increase in adult education institutions and organisations led to a higher demand for adult educators. Traditionally, they were schoolteachers, clergy or specialists in certain fields, giving lectures in the tradition of the ‘extensive’ teaching approach of popular education. However, this was a highly contested field. Around 1910, a discussion about the ‘extensive’ or ‘intensive’ approach of popular education started among practitioners of adult education. It was revived in the beginning of the 1920s, when different kinds of institutions for adult education were founded. The need for more and better educated practitioners led to a professionalisation of the field, wherein universities started to teach adult educators (Friedenthal-Haase 1991).

The professionalisation process influenced not only the practice of adult education but also research. Interested scholars from different backgrounds institutionalised research networks such as the Hohenrodter Bund, which initiated the Deutsche Schule für Volksforschung (German Institute for Folk Research), and the Institut für Sozialforschung (Institute for Social Research) at the University of Cologne was founded by Paul Honigsheim and Leopold von Wiese. In 1926, Gertrud Hermes founded the Institut für freies Volksbildungswesen (Institute for Popular Education) at the University of Leipzig.

Through these institutions, the first major empirically oriented studies using qualitative and quantitative methods were carried out in the following fields:

-

overviews concerning adult education practice

-

research concerning target groups and participants

-

research concerning adult education institutions

-

professionalisation processes

-

international-comparative research.

However, this highly prolific period of adult education practice and research came to an immediate end with the assumption of power by the National Socialist Workers’ Party in 1933. The independent and pluralistic adult education system of the Weimar Republic was prohibited. The protagonists either left Germany, or were arrested by the Nazi-regime and sent to concentration camps. Some of them did survive, but were suspended by the new regime (Feidel-Merz 1999).

4.2 Adult Education Research in the Federal Republic of Germany 1949–2000

The revival period of adult education research took place in the late 1950s. At that point, adult education practice was re-established and even intensified compared to the time before 1933. In the period of occupation, 1945 until the foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, the Western Allies, mainly the British and the Americans, saw adult education as a means for the democratisation of the adult population and supported the re-introduction of a pluralistic system of adult education. Their main interest was to re-establish and expand the adult education centres, but other organisations, such as churches, trade unions, employers and employer organisations were also encouraged to establish their own institutions. In the 1950s, the system was expanded further. Private investors entered the scene, laying the groundwork for the diverse publicly and privately funded adult education system, which still exists today (Zeuner 2015).

Whereas the adult education system was established step-by-step by different players, mirroring different aims and objectives, adult education science and research took additional time to be re-established. It was only at the end of the 1950s that the first chair of adult education, specialising in education for democracy, was established at the Freie Universität Berlin. Following the expansion of the educational system in the late 1960s, newly founded universities (such as Bochum, Essen and Bremen) and colleges of education (Hannover, Flensburg) incorporated adult education in their curricula for education science and therefore established chairs for adult education. This was also true for traditional universities such as Münster, Trier, Cologne, and Hamburg. There were more to follow, and in the 1990s, about 40 chairs of adult education existed in the Federal Republic of Germany, at least one in each of the federal provinces. In different ways, these chairs of adult education have shaped the research of adult education since the 1970s.

Before this took place, other developments influenced the evolution of adult education research: The Deutscher Volkshochschul-Verband, DVV (German Adult Education Association) established in 1953 founded the Pädagogische Arbeitsstelle des Deutschen Volkshochschulverbands, PAS (Institute for Didactics of Adult Education; in 1994, renamed Deutsches Institut für Erwachsenenbildung) in 1957. The first two long-standing directors of the PAS, Willy Strzelewicz (1905–1986) and Hans Tietgens (1922–2009), actively initiated research in adult education in the 1950s and 1960s. Through their work at the PAS, which collaborated closely with practitioners at the adult education centres, they were confronted first hand with a series of emerging problems.

One of the most urgent questions addressed, which is still a pressing issue, concerns the exclusion of certain target groups. In the 1950s and 1960s, these groups were identified as workers and women. The first study concerning participation in adult education was published by Wolfgang Schulenberg in 1957: Ansatz und Wirksamkeit der Erwachsenenbildung. He discussed the contradictions between the favourable opinion about education and the actual participation rates. In the study, 63 groups of 1039 people were asked about their educational awareness and attitudes. The groups represented the social stratification of the population to some extent (Schulenberg 1957, pp. 10–11). The prevalent reasons given for non-participation were work-overload, insufficient previous education or lack of money. Also, a discrepancy between the appreciation of education and individual behaviour was detected.

This study was followed by the study Bildung und gesellschaftliches Bewusstsein, published in 1966 by Willy Strzelewicz, Hans-Dietrich Raapke and Wolfgang Schulenberg. In the so-called ‘Göttingen Study’, a three-stage study was presented which included a representative survey of 1850 people, 34 group discussions and 38 individual interviews. The aim was to work out individual educational concepts and attitudes towards education and possible differences according to the social situation. The researchers wanted to know ‘what ideas the general public associates with the concept of education, what the population believes belongs to education, what it helps to achieve, what distinguishes a person who is thought to be educated’ (Strzelewicz et al. 1966, p. 39). The authors found a ‘social-differentiating syndrome’ of education and a ‘person-differentiating syndrome’. The former referred to individuals coming from a lower social status, characterised by attributes such as lower formal qualifications, social positions and prior knowledge. The latter referred to individuals coming from an upper social status, characterised by a higher educational background and income.

These two studies were ground-breaking in outlining both the research interests and methodological approaches. Up until this point, systematic reflections on the reciprocal influences of attitudes towards education and the social and educational background of the respondents had been scarce. The studies were later labelled ‘core studies’ because they set the standards for data collection and interpretation, as well as for grounding it in a sociological understanding of adult education. The studies showed that the social embeddedness of adults is crucial for their learning and educational experiences and should therefore be considered as a framework for adult education practice (Schlutz 1992). Other studies followed suit, like the ‘Oldenburg Study’ (Schulenberg et al. 1978). After the turn of the century, research concerning participation in adult education became increasingly important, and often, the Göttingen study was referred to as having been a forerunner (Barz and Tippelt 2007; Bremer 2007).

In the 1970s, another strand of research emerged, which was later described as ‘core studies’ (Schlutz 1992, pp. 45). Two of these studies became particularly prominent. The so-called ‘Hannover-Study’ analysed teaching and learning processes in adult education classes (Siebert and Gerl 1975). The so-called ‘BUVEP-Study’ Bildungsurlaubs-Versuchs- und Entwicklungsprogramm, BUVEP (Evaluation programme on paid educational leave) looked at the learning processes of participants during courses of paid educational leave (Kejcz et al. 1979).

While Siebert first aimed at investigating the outcome of teaching-learning processes in a positivist sense, i.e. decomposing the learning process into observable behavioural units and individual responses, he later recognised that questions about the social context of learners needed to be tackled. In the course of the study, the project developed from a quantifying analytical model to a qualitatively interpretive approach (Zeuner and Faulstich 2009, p. 64).

The BUVEP-study was supported by the government as a so-called ‘model project’. They aimed at developing educational policy guidelines for a further introduction of educational leave in order to create the conditions for individuals to receive an education corresponding to their talents, abilities and willingness to learn (Kejcz et al. 1979, p. 20).

These important empirical studies were always supplemented by a vast number of smaller studies, often PhD dissertations, supervised at universities and often supported by the PAS. So, by the end of the 1960s, a pluralistic scene of adult education research was set, but it was by no means systematically expanded or even regulated.

4.3 The Role of the Scientific Community

In 1971, the professors in the newly established chairs of adult education and related fields founded the ‘Division Adult Education’ of the German Educational Research Association (GERA) (Schmidt-Lauff 2014). Its members aimed at supporting research in adult education, furthering discussions and scientific co-operation, and strengthening the identity of the emerging research field. Starting in 1971, the division organised regular annual conferences.Footnote 2

At the turn of the century, representatives of the division published the so-called Forschungsmemorandum zur Erwachsenenbildung (Memorandum concerning research in adult education) (Arnold et al. 2000). The memorandum came into being at a time when questions about lifelong learning were being intensively discussed, especially at the level of education policy. Adult education – which, in Germany, in contrast to other countries, has been equated with lifelong learning for many years – suddenly found itself in competition with education-specific approaches to different age groups, such as early childhood, adolescence or older adults. The objective of the memorandum was ‘to identify, classify and name priorities and necessary questions in an increasingly important area of educational research’ (Arnold et al. 2000, p. 4) in order make this field of research more visible within the scientific community, as well as for potential sponsors.

The memorandum refers to the following research fields and topics:

-

Learning of adults

-

Knowledge structures and competence requirements

-

Staff in adult education

-

Institutionalisation

-

System and politics.

It concludes with recommendations for the implementation of the research strategies. Considering the topics of the so-called ‘core studies’, it is interesting to note that questions concerning participation and participants are not mentioned explicitly. They can be tackled in each of the topics, but the crucial question of who is participating and why – and why not – is somewhat hidden behind the scene.

Two years later, the Memorandum zur historischen Erwachsenenbildungsforschung (Memorandum on historical adult education research) was published (Ciupke et al. 2002). It highlights that the relevance of historical research in adult education studies is ‘… to expand the adult education space of experience in a diachronic perspective and thus to confront contemporary practice with other possibilities which were historically realized’ (Ciupke et al. 2002, p. 9). First describing the state of historical adult education research, the authors then go on to discuss further perspectives and questions according to the structure developed in the memorandum of 2000, supplemented by the ‘history of science’ field. The memorandum points out the future tasks and focal points of historical adult education research and reflects on topics, as well as on recommendations for research funding.

Both memoranda are thus guidelines, looking at research perspectives and strategies. However, they should not be read as a review of the current state of research or as a comprehensive overview. This kind of work is still pending, with the exception of Born’s book (Born 1991), and in terms of current research up to 2008, of Zeuner and Faulstich’s study from 2009. The Handbook of Qualitative Research on Adult and Further Education by Dörner and Schäffer (2012) focuses on questions regarding the theoretical frameworks of adult education research and on the methodological approaches. In section D of the book, several topics of adult education research concerning profession, milieu, gender, generation, counseling, management, learning (various topics), time and emotions are tackled in articles by different authors.

5 Trends and Topics in Adult Education Research Since 2000

Over the last 20 years, adult education research in Germany has been influenced by different trends. On the one hand, small-scale, individual research still represents the larger proportion of research (Nuissl 2010, p. 406). It can be systemised according to the research fields in the memorandum of adult education research (Arnold et al. 2000) and the outline developed by Zeuner and Faulstich in 2009. On the other hand, international educational policies initiated by supranational agencies such as the UNESCO, the OECD, the World Bank and, on the European level, the European Commission, have influenced adult education research directly and indirectly. Also, mostly reacting to international developments such as the ongoing discussion on lifelong learning, educational policy and educational politics in Germany have become more influential regarding national research agendas since the turn of the century (Schreiber-Barsch and Zeuner 2018, p. 27).

5.1 Topics of Adult Education Research

Within the scope of this article, it is impossible to summarise the results of adult education research from the last 20 years. Such an attempt was made by Zeuner and Faulstich (2009) up to the year 2008, and recent developments can be seen in the so-called ‘research map’ of the German Institute for Adult Education (DIE 2018; Ludwig and Baldauf-Bergmann 2010).

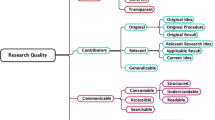

The difference lies in the categorisation of the research topics. Whereas the research map used the systematic approach of the research memorandum of 2000 (Arnold et al. 2000), Zeuner and Faulstich (2009) developed their own systematic approach. In the following, I will outline their findings. They decided to differentiate the following main categories and sub-categories:

-

1.

Learning and teaching:

-

Learning research concerning empirical approaches, subject-oriented approaches, informal learning, resistance towards learning, neurophysiological research

-

Teaching research concerning methodological approaches, development of didactical concepts, self-organised and self-directed learning, the role of the media

-

Programme-planning and course-development

-

-

2.

Learners: addressees, target groups, participants

-

‘Core studies’ concerning addressees and milieu-oriented research according to Pierre Bourdieu

-

Target groups according to their consideration from the historical perspective: workers, women, unemployed people, migrants, older adults, educationally disadvantaged people

-

Research concerning participants

-

Biographical and socialisation research

-

-

3.

Institutions, cooperation, support-structures

-

Adult education providers and institutions: historical and current developments, organisational learning

-

Networks and co-operation in adult education

-

Organisation, marketing and management in adult education

-

Support structures for further training

-

-

4.

Contents/topics of adult education

-

Further vocational education and training

-

General adult education including programme-analysis and topics

-

Education for democracy/citizenship education

-

Cultural adult education

-

-

5.

Staff in adult education

-

Training of adult educators including research on professional development

-

Professional areas of adult educators including full-time and part-time staff

-

Staff in further vocational training

-

Biographical research on the professional development of adult educators

-

-

6.

Development of the adult education system

-

Politics, economy and law and their influence on adult education

-

Resources for adult education, financial support

-

International and comparative adult education research: methodology and results

-

-

7.

Historical research in adult education

-

Objectives of historical adult education research and summery of results

-

Fields of historical research: Historical research of ideas, social-historical research, historical developments concerning institutions and organisations of adult education, history of continuing vocational training

-

History of adult education in the German Democratic Republic (GDR)

-

Results of historical international-comparative research in adult education

-

This systematisation and the studies examined more closely mirror the fact that most adult education research is oriented towards better understanding and more effectively explaining the practice of adult education. It essentially included studies by researchers who are closely affiliated with adult education as a discipline. However, other relevant disciplines include psychology, which tackles questions around the learning processes of adults; history, which studies the historic development of adult education; political science, which researches within the field of citizenship education and migration, and sociology, which investigates questions concerning social background and education. However, they do not seem to be as prominent in the discussion as Rubenson and Elfert (Chap. 2) suggest for the development of adult education research elsewhere.

Most of the studies examined depict the problems and questions arising on the three practice levels of adult education: the micro-level, concerning learning and teaching-processes; the meso-level, concerning the institutions, organisations, and providers of adult education, the different stakeholders (staff, participants), as well as the topics and programmes; the macrolevel, concerning politics, policy, and adult education law and the economic conditions and influences. This systematisation is derived from the German arrangement of adult education, which is embedded in the educational system and therefore at least in part supported by the government. Certain characteristics and features may be common in other countries, but some may be unique.

6 Discussion

In this chapter, I intended to give an overview of the development of adult education research in Germany from its beginning to the present day. From my point of view, the following basic conditions are important in order to understand the developments: First, adult education research usually refers to adult education practice when developing research questions and interests. Up to the 1970s, its main objective was to support and improve the practice. The topics mainly concerned participation in adult education, the learning processes of adults, the professionalisation of the staff, and the micro- and meso-levels of adult education. The overall question has been how to encourage more adults to participate in adult education.

A more recent development in German adult education research is policy-induced studies as a reaction to national and international developments and trends. Nationally, policies concerning adult education gradually emerged in the 1970s, after the so-called ‘Deutscher Bildungsrat’ (German Education Council 1966–1975) published the ‘Strukturplan für das Bildungswesen’ (‘Structural plan for education’) in 1970. It stated the importance of adult education concerning questions such political participation and the employability of the workforce. For the first time in the Federal Republic of Germany, adult education was recognised as the fourth pillar of the educational system, along with the primary education and secondary education provided by schools, vocational training and higher education (Zeuner 2015, pp. 11–12).

The expansion of the educational system, which took place in the 1970s, also affected adult education at different levels and dimensions: Several federal states (Bundesländer) passed laws on adult education which regulated the provision of and access to adult education and tackled questions such as the quality of courses, the professionalisation of the staff, the expansion of the necessary infrastructure, and so on. At the same time, chairs of adult education were established at several universities, stressing the need for research. Following the first report on adult education, others were published, some of which were policy papers. Because it became clear that adult education was a fragmented field, and that at the same time, there was something like a ‘black box’ regarding its overall performance within the educational system, it was placed on the political agenda for the first time. Beginning in the 1980s, the federal Ministry of Education began to support such research and has continued to do so.

Two strands are prevalent today: On the one hand, evaluations and policy research have been supported by the national and regional ministries of education concerning topics such as participation in adult education, infrastructure and networks for lifelong learning, counseling and support and, more recently, literacy. On the other hand, after the turn of the century, international educational policy began to be more impactful, mainly due to international developments on the European, as well as the global level. Within the scope of the international lifelong learning discourse, the German government started national research programmes. They mirrored and supplemented the policy agendas of the European Union, on the one hand, and of the UNESCO and the OECD, on the other.

Initially, the adult education research initiated by the German government aimed at gaining knowledge concerning participation in adult education, as this was considered to be an important asset in view of economic competition. Later, aspects such as educational governing came into view, and educational policy gained momentum through international benchmarking. Therefore, adult education research became more important. However, the question arises of whether this kind of research is still being conducted independently or if it solely serves the needs of the government.

Comparing the development of adult education research in Germany with the international findings presented by Rubenson and Elfert (Chap. 2), I see parallels as well as discrepancies. The authors stress two facts concerning the development of adult education research from an international point of view:

First, they consider adult education research to be an increasingly fragmented field. Referring to Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of scientific fields which are highly independent and at the same time ‘are impacted by social structure and institutional power’ (Rubenson and Elfert 2015, pp. 125–126), they consider adult education research as being effected by both ‘the broad social world in which the field is embedded and the scientific field itself, with its own rules of functioning’ (Rubenson and Elfert 2015, p. 126). This twofold structure influences the development of research topics, questions, interests, and methodological approaches alike.

An examination of adult education research in Germany reveals that the same findings are applicable. The topics and questions are manifold, as they have multiplied over the last 20 years. Certain topics, such as workplace education and further training, are investigated by researchers from scientific fields other than adult education research. Therefore, it could be useful to consider the ‘hollowing out of the field’ (Rubenson and Elfert 2015, p. 135), i.e. to challenge the field of adult education compared with other scientific fields, which are co-opting its topics. For example, research regarding learning processes is now dominated by psychological research.

Concerning the research methods, they range from the small-scale, qualitative approaches used in dissertations or smaller, individual research projects to the policy-induced, quantitative, large-scale assessments which are regularly financed by the government. This kind of research has increased considerably since the turn of the century.

Concerning the focus of adult education research, Rubenson and Elfert (Chap. 2) state that the following five categories seem to be the most relevant: adult learning, participation, gender/diversity, adult education as a movement, and the analysis of publication patterns. Compared to the findings of Zeuner and Faulstich (2009), the first two topics have traditionally been very important in adult education research in Germany, whereas the other three have been tackled less often. Gender, mainly looking at women as participants in adult education, was an important topic in the 1990s. Questions concerning diversity have become more relevant in recent times with the increase of migration, with a focus on the questions of inclusion and exclusion. Adult education as a movement has primarily been examined from a historical point of view, focusing on the workers’ educational movement in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and – although less commonly – on increasing disciplinary identity as well as legitimation. The analysis of publication patterns using discourse analysis seem to be rather marginalised. One exception is the analysis of the lifelong-learning discourse (Schreiber-Barsch and Zeuner 2018). However, these impressions need to be verified further: An analysis of the research map published by the German Institute for Adult Education (2018) could be a starting point.

According to the second finding of Rubenson and Elfert (Chap. 2), the results of adult education research are increasingly being criticised as not useful for practitioners, ‘but also the policy community voice their disappointment with adult education research, and we note a disconnect between academic adult research and policy-related research’ (p. 121). It is difficult to decide whether this observation is also true for adult education research in Germany. As I stated earlier, since the beginning, there has been a close relationship between adult education research and practice. The research questions have been drawn from practice, and this has influenced and shaped the scientific field for a long time. Most of the time, both sides have been aware of the fact that the findings and the results of research need to be reflected and ‘translated’ in order for them to become available for practice. Perhaps the mutual expectations were rather realistic. When it comes to policy-induced or evaluation research, the expectations concerning its applicability and usefulness may be higher. I cannot say whether they have been met or not.

However, another aspect that Rubenson and Elfert (Chap. 2) discuss towards the end of their article also seems to apply to German adult education research: The scientific field is inclined to do more policy-related research in order to obtain more funding, and therefore, seemingly, to become more important as a scientific field. However, I agree with Rubenson’s and Elfert’s (Rubenson and Elfert 2015 and Chap. 2) warning concerning the risks this poses:

Thus, while the policy-related interest in adult education research may provide some new opportunities for the development of more major research programs, something that has been lacking in the field, it also provides a danger of moving the research agenda away from classical adult education concerns about democracy and social rights and ‘forcing’ the researchers to focus on a narrow politically-defined research agenda (p. 136).

The developments in Germany are similar to those Wildermeersch and Olesen (2012) describe on an international level. They state that beginning in the 1980s, and increasingly in the 1990s and later, the research has been aimed primarily at questions of how to improve the learning processes of adults in order to increase their chances in the labour market. Employability, combined with topics such as qualifications and competences, became paramount. Wildermeersch and Olesen’s (2012) statement that the objectives of adult education have changed from emancipation (the ‘redistribution of opportunities on a collective level’) to empowerment (the ‘responsibility of one’s own self-development’) has also become valid for Germany, which has influenced both adult education practice and research (pp. 98–99).

From my point of view, this mirrors the long-standing debate about whether learning or Bildung should be the main priority of adult education. As a reaction to the national and international discussions concerning learning outcomes and their relevance for the labour market, the notion of learning has become prevalent over the last 15 years. Learning outcomes are seen as a means of individual empowerment and are mostly the responsibility of the individual. Therefore, the research has focused on, inter alia, questions of individual learning competences, self-directed learning processes, informal learning, and learning en-passant.

However, due to political and social developments characterised by an increasing gap between the rich and the poor, the decrease of the social welfare state resulting in increasing competition between different social milieus, and growing migration and the need for integration and inclusion, adult education is facing new and different challenges. This has also led to a re-awakening of the discussions concerning Bildung as defined by critical theory as a means of individual and collective emancipation. Adult education research is again starting to investigate educational processes from this point of view, focusing, on the one hand, on its biographical impact. On the other hand, action research approaches are increasingly being used to examine collective educational processes concerning questions regarding community development, collective political initiatives, and so on.

Notes

- 1.

Pädagogische Arbeitsstelle des Deutschen Volkshochschulverbandes (PAS) renamed in 1997 in “Deutsches Institut für Erwachsenenbildung” (DIE; German Institute for Adult Education).

- 2.

See Division of Adult Education 2018 for a list of topics.

References

Arnold, R., Faulstich, P., Mader, W., Nuissl von Rein, E., & Schlutz, E. (2000). Forschungsmemorandum für die Erwachsenen- und Weiterbildung. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsches Institut für Erwachsenenbildung. Retrieved April 2, 2018, from https://www.die-bonn.de/esprid/dokumente/doc-2000/arnold00_01.pdf

Barz, H., & Tippelt, R. (Eds.). (2007). Weiterbildung und soziale Milieus in Deutschland (Vol. Vol. 2, 2nd ed.). Bielefeld: Bertelsmann Verlag.

Born, A. (1991). Geschichte der Erwachsenenbildungsforschung. Eine historisch-systematische Rekonstruktion der empirischen Forschungsprogramme. Bad Heilbrunn Obb: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

Bremer, H. (2007). Soziale Milieus, Habitus und Lernen. Zur sozialen Selektivität des Bildungswesens am Beispiel der Weiterbildung. Weinheim: Juventa.

Ciupke, P., Gierke, W., Hof, C., Jelich, F.-J., Seitter, W., Tietgens, H., & Zeuner, C. (2002). Memorandum zur historischen Erwachsenenbildungsforschung. Bonn: DIE. Retrieved April 2, 2018, from https://www.die-bonn.de/esprid/dokumente/doc-2002/ciupke02_01.pdf

Deutscher Bildungsrat. (1970). Strukturplan für das Bildungswesen. Empfehlungen der Bildungskommission. Stuttgart: Ernst Klett.

Deutsches Institut für Erwachsenenbildung. (2018). Forschungslandkarte. Retrieved April 2, 2018, https://www.die-bonn.de/weiterbildung/forschungslandkarte/recherche.aspx

Dewe, B., Günter, F., & Huge, W. (1988). Theorien der Erwachsenenbildung. Ein Handbuch. München: Max Hueber Verlag.

Division Adult Education of the German Educational Research Association (GERA). (2018). Topics of workshops since 1971. Retrieved April 2, 2018, from http://www.dgfe.de/en/sections-commissions/division-9-adult-education/tagungen.html

Dörner, O., & Schäffer, B. (2011). Neuere Entwicklungen in der qualitativen Erwachsenenbildungsforschung. In R. Tippelt & A. von Hippel (Eds.), Handbuch Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung (5th ed., pp. 243–261). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Dörner, O., & Schäffer, B. (Eds.). (2012). Handbuch Qualitative Erwachsenenbildungs- und Weiterbildungsforschung. Opladen: Budrich.

Feidel-Merz, H. (1999). Erwachsenenbildung im Nationalsozialismus. In R. Tippelt (Ed.), Handbuch Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung (2nd ed., pp. 42–50). Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Friedenthal-Haase, M. (1991). Erwachsenenbildung im Prozeß der Akademisierung. Der staats- und sozialwissenschaftliche Beitrag zur Entstehung eines Fachgebiets an den Universitäten der Weimarer Republik unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Beispiel Kölns. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Hartmann, L. M., & Penck, A. (1904). Antworten auf die vom Wiener Ausschuss für volkstümliche Universitätsvorträge veranstaltete Nutzen der Universitätskurse. Zentralblatt für Volksbildungswesen, 4, 81–102.

Kade, S. (1999). Qualitative Erwachsenenbildungsforschung – Methoden und Erkenntnisse. In R. Tippelt (Ed.), Handbuch Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung (2nd ed., pp. 240–359). Opladen: leske+budrich.

Kejcz, Y., Monshausen, K., Nuissl, E., Paatsch, H., & Schenk, P. (1979). Das Bildungsurlaubsversuchs- und Entwicklungsprogramm. BUVEP-Endbericht (Vol. 1–8). Heidelberg: esprint.

Klafki, W. (1996). Neue Studien zur Bildungstheorie und Didaktik. Zeitgemäße Allgemeinbildung und kritisch-konstruktive Didaktik (5th ed.). Weinheim: Beltz.

Ludwig, J., & Baldauf-Bergmann, K. (2010). Profilbildungsprobleme in der Erwachsenenbildungsforschung. Report. Zeitschrift für Weiterbildungsforschung, 33(1), 65–76. Retrieved April 26, 2018, from https://www.die-bonn.de/doks/ludwig1001.pdf

Nuissl, E. (2010). Erwachsenenbildung/Weiterbildung. In R. Tippelt & B. Schmidt (Eds.), Handbuch Bildungsforschung (3rd ed., pp. 405–420). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Rubenson, K., & Elfert, M. (2015). Adult education research: Exploring an increasingly fragmented map. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 6(2), 125–138.

Schlutz, E. (1992). Leitstudien der Erwachsenenbildung. In W. Gieseke, E. Meueler, & E. Nuissl (Eds.), Beiheft zum Report. Empirische Forschung zur Bildung Erwachsener. Dokumentation der Jahrestagung 1991 der Kommission Erwachsenenbildung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft (pp. 39–55). Frankfurt am Main: Arbeitsstelle des Deutschen Volkshochschulverbandes.

Schmidt-Lauff, S. (Ed.). (2014). Vergangenheit als Gegenwart – Zum 40-jährigen Bestehen der Sektion Erwachsenenbildung der DGfE. Opladen: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

Schreiber-Barsch, S., & Zeuner, C. (2018). Lebenslanges Lernen: Positionen, Konzepte, Programmatiken, Befunde. In C. Zeuner (Ed.), Enzyklopädie Erziehungswissenschaft Online. Fachgebiet: Erwachsenenbildung. Weinheim und München: Beltz Juventa. Retrieved April 26, 2018, from https://www.beltz.de/fachmedien/erziehungs_und_sozialwissenschaften/enzyklopaedie_erziehungswissenschaft_online_eeo.html?tx_beltz_educationencyclopedia%5Barticle%5D=38683&tx_beltz_educationencyclopedia%5Baction%5D=article&tx_beltz_educationencyclopedia%5Bcontroller%5D=EducationEncyclopedia&cHash=5459196bca2a5be31b3a45d950391273

Schulenberg, W. (1957). Ansatz und Wirksamkeit der Erwachsenenbildung. Stuttgart: Klett.

Schulenberg, W., Loeber, H.-D., Loeber-Pautsch, U., & Pöhler, S. (1978). Soziale Faktoren der Bildungsbereitschaft Erwachsener. Materialien zur Erwachsenenbildung. Stuttgart: Klett.

Siebert, H. (2011). Theorien für die Praxis (3rd ed.). Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann Verlag.

Siebert, H., & Gerl, H. (1975). Lehr- und Lernverhalten Erwachsener. Braunschweig: Westermann Taschenbuch.

Strzelewicz, W., Raapke, H.-D., & Schulenberg, W. (1966). Bildung und gesellschaftliches Bewußtsein. Stuttgart: Enke.

Tietgens, H. (1991). Ansätze zu einer Theoriebildung. (Diskussions- und Erkenntnisschritte der Sektion Erwachsenenbildung der DGfE). In W. Mader (Ed.), Zehn Jahre Erwachsenenbildungswissenschaft (pp. 45–69). Bad Heilbrunn Obb: Verlag Julius Klinkhardt.

Wildermeersch, D., & Olesen, H. S. (2012). Editorial: The effects of policies for the education and learning of adults – From ‘adult education’ to ‘lifelong learning’, from ‘emancipation’ to ‘empowerment’. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 3(2), 97–101.

Zeuner, C. (2010). Vuxenutbildningens början i Schleswig-Holstein. Folkhögskolan Rendsburg (1842–1848) mot bakgrund av danks-tysk politik. In F. L. Nilsson & A. Nilsson (Eds.), Två sidor av samma mynt? Folkbildning och yrkesutbildning vid de nordiska folkhögskolorna (pp. 57–79). Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

Zeuner, C. (2015). Erwachsenenbildung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland von 1970 bis 1990. In C. Zeuner (Ed.), Enzyklopädie Erziehungswissenschaft Online. Fachgebiet: Erwachsenenbildung. Weinheim und München: Beltz Juventa, https://doi.org/10.3262/EEO16150349. Retrieved April 2, 2018, from //www.erzwissonline.de, www.content-select.com/10.3262/EEO16150349

Zeuner, C., & Faulstich, P. (2009). Erwachsenenbildung – Resultate der Forschung. Weinheim: Beltz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Zeuner, C. (2019). Adult Education Research in Germany: Approaches and Developments. In: Fejes, A., Nylander, E. (eds) Mapping out the Research Field of Adult Education and Learning. Lifelong Learning Book Series, vol 24. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10946-2_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10946-2_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-10945-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-10946-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)