Keypoints

-

1.

The contribution of non-auditory pathways to the pathology of tinnitus has become more and more evident.

-

2.

Because many different stimuli can modulate tinnitus (forceful muscle contractions of the head and neck, eye movements, pressure of myofascial trigger points, cutaneous stimulation of the face, orofacial movements, etc.), it is important to diagnose somatosensory tinnitus and somatosensory modulation of tinnitus.

-

3.

This chapter discusses how somatosensory tinnitus and somatosensory modulation of tinnitus can be diagnosed, mostly by means of anamnesis and physical evaluation. The chapter provides practical information to the health care professionals regarding such diagnosis.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

It is now generally accepted that many incidences of tinnitus can be evoked or modulated by inputs from the somatosensory system, the somatomotor, and the visual-motor systems. Some individual’s tinnitus can be modulated by stimulation of parts of the somatosensory system. Such tinnitus is known as somatosensory tinnitus (other names have been used and the name somatosensory tinnitus has been used for other forms of tinnitus). Somatosensory tinnitus is different from tinnitus that is not affected by activations of non- auditory systems. We will call such tinnitus auditory tinnitus. The effect of somatosensory stimulation on tinnitus can be demonstrated by inducing forceful muscle contractions of the head, neck, and limbs [1–3]; by orofacial movements [4–8]; by applying pressure to myofascial trigger points (MTP) [9]; or by stimulating the skin of the face and hands [4, 10]. Eye movements can often induce tinnitus or modulate existing tinnitus [5]. Among these and other types of modulating factors that have been described (see Chap. 43), the influence of stimulating head and neck regions on the auditory pathways are particularly interesting.

Definition of Somatosensory Tinnitus

The terms “somatosensory tinnitus” and “somatic tinnitus” have been used with different meanings. Efforts are now made to differentiate between somatosensory tinnitus (primary origin in head and neck disorders) and somatosensory modulation of tinnitus.

Somatosensory Tinnitus

Somatosensory tinnitus is suspected when a patient’s history shows at least one of the following events has occurred before the onset of tinnitus:

-

Head or neck trauma

-

Manipulation of teeth or jaw or cervical spine

-

Recurrent pain episodes in head, neck, or shoulder girdle

-

Increase of both pain and tinnitus at the same time

-

Inadequate postures during rest, walking, working, or sleeping

-

Intense periods of bruxism (grinding of the teeth) during day or night

Other forms of stimulation of structures of the head and neck may or may not cause the loudness, pitch, or localization of somatosensory tinnitus to change.

The most important characteristic of somatosensory tinnitus is that it is related to problems of the head and neck, rather than to problems of the ear.

The complexity of somatosensory tinnitus requires that patients with this disorder be evaluated by an integrated team including an experienced dentist and physiotherapist (or similar professions, depending on the organization of local health care structures) to evaluate possible bone and muscular disorders of the face and neck as well as dental problems. Prompt diagnosis is important because treatment must be started as early as possible to obtain the best results (see Chap. 80).

Somatosensory Modulation of Tinnitus

Somatosensory modulation of tinnitus may be perceived as transient changes in loudness, pitch, or localization of the tinnitus. Such modulation of tinnitus can be induced in individuals with either auditory or somatosensory tinnitus. Since the tinnitus of many individuals can be elicited or modulated by somatosensory stimulation (65–80%) [1, 2], all patients who seek help for their tinnitus should be tested for somatosensory modulation. If a patient spontaneously reports that his/her tinnitus changes temporarily during common daily movements of the jaw or neck (opening mouth, clenching teeth, or turning head) or by applying pressure on the temples, mandible, cheek, mastoid, or neck with a fingertip, it is a strong sign that the patient has somatosensory modulation of tinnitus. Other signs of somatosensory modulation may become evident when a professional examines the patient and actively searches for modulation of the tinnitus by applying different kinds of stimuli to different locations on the patient’s body. The patient may mention an immediate change in the loudness of the tinnitus (increase or decrease assessed by a visual analogue scale) or changes in the pitch or the localization of the tinnitus. If this occurs during at least one maneuver involving the somatosensory, somatomotor, or visual-motor systems, it is a strong sign that the patient has somatosensory tinnitus. The effect of many kinds of modulation is short lasting and it is difficult to use a questionnaire to evaluate tinnitus before and after such maneuvers. However, a simple instrument such as a visual analogue scale can be used to quickly evaluate the magnitude of the induced changes in tinnitus.

Different stimuli can be used to detect somatosensory modulation of a patient’s tinnitus, such as active jaw movements (with and without resistance by the examiner), opening and closing the mouth, moving chin forward and backward, or lateralizing chin right and left. Passive muscular palpation can be used to find MTPs or tender points in the masseter, temporalis, and lateral pterygoid muscles. The fatigue test (teeth closed with spatula between them in anterior, right, and left positions for a duration of 1 min) is another useful test that can reveal somatosensory tinnitus.

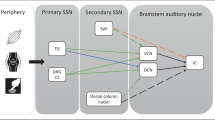

Such movements increase the signals elicited by the tense muscles in the area innervated by the sensory part of the trigeminal nerve, which is anatomically and physiologically connected to the acoustic pathways [11].

Active neck movements (with and without resistance by the examiner) such as moving neck forward and backward, rotation right and left, and lateralization right and left can be used to test if signals from the neck can modulate the patient’s tinnitus. Passive muscular palpation searching for MTPs or tender points in the trapezius (upper fibers), sternocleidomastoid (sternal division), splenius capitis (near the mastoid process), and splenius cervicis are other important tests.

The jaw and upper cervical spine are considered to be a part of an integrated motor system; therefore, observing the posture of the patient is also important for diagnosis and treatment of tinnitus that can be modulated with somatosensory stimulation. For example, if a patient has the mandible and/or neck protruded forward, this might suggest an attempt to compensate for wrong dental occlusion.

Gaze-Evoked Tinnitus or Gaze-Modulated Tinnitus

Eye movements can both cause tinnitus and modulate tinnitus (gaze-evoked tinnitus or gaze-modulated tinnitus) [5]. Influence of gaze on tinnitus can be tested by having the patient start looking straight forward (a neutral position) and then gaze first to the maximal right and then left; after that, looking upwards and downwards. Each position should be maintained for 5–10 s. With the patient placed in a silent environment, changes in tinnitus may occur during each eye movement.

Methods for measuring modulation of tinnitus are not yet standardized. Some centers only describe it as “present” or “absent,” and some use a visual analogue scale (from 0 to 10 or from 0 to 100). Toward standardization, we propose a scale for modulation of tinnitus that is centered at 0 (rest state of tinnitus) and ranging from minus 5 (disappearance) to plus 5 (biggest increase ever thought).

Other Indications of Somatosensory Tinnitus

Bone problems of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and the neck (osteophits, arthrosis, spondylosis, etc.) may justify the presence of pain and management of accompanying muscular problems (which also can occur in isolation). Such bone problems can seldom be reversed completely, but an approach directed to treat the muscular tension may also lead to control of somatosensory tinnitus and the associated pain (Chap. 80). It may therefore be recommended that the TMJ and neck disorders may be diagnosed and treated to allow better tinnitus control.

Although modulation of tinnitus can occur regardless of the presence of pain, some extra clues to diagnosing somatosensory tinnitus may be added if pain is also included in the following rationale:

-

Does the patient have frequent regional pain?

-

If so, is it in the head, neck, and shoulder girdle?

-

If so, has it a similar duration as the patient’s tinnitus?

-

If so, does the patient’s tinnitus become worse when the pain increases?

In general, a patient’s history, together with a clinical examination by a physician might be sufficient for diagnosing temporomandibular and neck disorders in most patients, but complimentary exams (X-ray, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging) may be helpful in reaching a firm diagnosis.

Myofascial Trigger Points

MTP are hyperirritable spots in skeletal muscles, which are associated with hypersensitive palpable nodules in taut bands. Basically, there are two kinds of MTPs: active or latent. Active MTP cause clinical pain complaint and refer patient-recognized pain during palpation. A latent MTP may have all the other clinical characteristics of an active MTP and always has a taut band that increases muscle tension and restricts range of motion. It does not provoke spontaneous pain and it is painful only when palpated (upon palpation, the latent MTP can provoke pain and altered sensation in its distribution expected from a MTP in that muscle) [12].

The diagnosis of active MTP is very important for the treatment of myofascial pain syndrome, for pain release, and possibly even for tinnitus relief.

The relationship between MTP, myofascial pain syndrome, and tinnitus has been studied during the preceding years (see Chaps. 9, 43, and 80). Tender points should also be identified and their possible modulation of the patient’s tinnitus must likewise be determined.

Palpation should be performed with sustained deep single-finger pressure during up to 10 s with a spade-like pad at the end of the distal phalanx of the index finger or through pincer palpation (thumb and finger) moving across the muscle band at the hypersensitive area (Figs. 52.1 and 52.2).

When a palpable taut band and spot tenderness is detected, the patient should be asked (Fig. 52.3) if he/she feels any sensation in other area besides the one being pressed upon; if the sensation is like the one that is a problem to the patient; and finally, if the loudness or pitch of the tinnitus changed.

The ten muscles in the head, neck, and shoulder girdle (infraspinatus, levator scapulae, trapezius, splenius capitis, splenius cervicis, scalenus medius, sternocleidomastoid, digastric, masseter, and temporalis) should all be examined for the presence of MTPs [12]. The examination is expected to reveal whether MTPs were present or not, and if so, in which muscles, in which side of the body relative to the tinnitus, and if palpation of one or more MTPs modulated the patient’s tinnitus. If tender points were present, the patient should be asked if palpation of the tender points affected their tinnitus.

Manual palpation of the muscles is the easiest way of examining patients for somatosensory tinnitus. However, a more objective measurement may be obtained using a hand-held force gauge with a rubber tip to measure the pressure required for eliciting MTP activity [pressure algometry (PA)]. PA has been used to document the tenderness of MTP and is also applied to measure the referred pain threshold and pain tolerance. The reliability and validity of measurements using PA have been established [13, 14]. Pre- and posttherapeutic effectiveness of various procedures on MTP have been assessed by measurement of pressure threshold with PA (Fig. 52.4).

Conclusions

The ability to correctly diagnose somatosensory tinnitus and somatosensory modulation of tinnitus relies mainly on the patient’s history and a thorough physical examination. However, these forms of tinnitus have only recently been studied in detail. Knowledge about the signs of these forms of tinnitus is therefore not generally known. Health care professionals may need to be informed about how to diagnose these forms of tinnitus in their daily routine of treating patients with tinnitus.

Abbreviations

- MTP:

-

Myofascial trigger points

- PA:

-

Pressure algometry

- TMJ:

-

Temporomandibular joint

References

Levine, RA. Somatic modulation appears to be a fundamental attribute of tinnitus. In: Hazell, JPW, ed. Proceedings of the Sixth International Tinnitus Seminar. London: The Tinnitus and Hyperacusis Center; 1999: 193–7.

Sanchez, TG; Guerra, GCY; Lorenzi, MC; Brandão, AL; Bento, RF. The influence of voluntary muscle contractions upon the onset and modulation of tinnitus. Audiol. Neurootol. 2002; 7: 370–5.

Sanchez, TG; Lima, AS; Brandao, AL; Lorenzi, MC; Bento, RF. Somatic modulation of tinnitus: test reliability and results after repetitive muscle contraction training. Ann. Otol. 2007; 116: 30–5.

Cacace, AT; Cousins, JP; Parnes, SM; McFarland, DJ; Semenoff, D; Holmes, T; Davenport, C; Stegbauer, K; Lovely, TJ. Cutaneous-evoked tinnitus. II. Review of neuroanatomical, physiological and functional imaging studies. Audiol. Neurootol. 1999; 4: 247–57.

Coad, ML; Lockwood, A; Salvi, R; Burkard, R. Characteristics of patients with gaze-evoked tinnitus. Otol. Neurotol. 2001; 22(5): 650–4.

Baguley, DM; Phillips, J; Humphriss, RL; Jones, S; Axon, PR; Moffat, DA. The prevalence and onset of gaze modulation of tinnitus and increased sensitivity to noise after translabyrinthine vestibular schwannoma excision. Otol. Neurotol. 2006; 27: 220–4.

Sanchez, TG; Pio, MRB. Abolição de zumbido evocado pela movimentação ocular por meio de repetição do deslocamento do olhar: um método inovador. Arq. Otorhinolaryngol. 2007; 11: 451–3.

Pinchoff, RJ; Burkard, RF; Salvi, RJ; Coad, ML; Lockwood, AH. Modulation of tinnitus by voluntary jaw movements. Am. J. Otol. 1998, 19: 785–9.

Rocha, CACB; Sanchez, TG; Siqueira, JTT. Myofascial trigger points: a possible way of modulating tinnitus? Audiol. Neurotol. 2008; 13: 153–60.

Sanchez, TG; Marcondes, RA; Kii, MA; Lima, AS; Rocha, CAB; Ono, CR; Bushpiegel, C. A different case of tinnitus modulation by tactile stimuli in a patient with pulsatile tinnitus. Presented at II Meeting of Tinnitus Research Initiative, Mônaco, 2007; 21–3.

Shore, S; Zhou, J; Koehler, S. Neural mechanisms underlying somatic tinnitus. Prog. Brain Res. 2007; 166: 107–23.

Travell, J; Simons, DG. Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual, Upper Half of Body. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

Fischer, AA. Pressure threshold meter: its use for quantification of tender spots. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1986; 67: 836–8.

Kraus, H; Fischer, AA. Diagnosis and treatment of myofascial pain. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 1991; 58: 235–9.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Tinnitus Research Initiative for the creation and support of the workgroup of Somatosensory Tinnitus and Modulating Factors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sanchez, T.G., Rocha, C.B. (2011). Diagnosis of Somatosensory Tinnitus. In: Møller, A.R., Langguth, B., De Ridder, D., Kleinjung, T. (eds) Textbook of Tinnitus. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-145-5_52

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-145-5_52

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-60761-144-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-60761-145-5

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)