Abstract

Comorbid psychiatric disorders are common in HIV infection. Mood disorders (e.g., depression) have received the most attention in the literature; however, neuropsychiatric features of apathy and irritability and severe mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) have also emerged as important comorbidities that warrant attention. While the former may develop secondary to infection, the latter are believed to place individuals at increased risk for contracting HIV and, once infected, poor HIV-related health outcomes. Psychiatric comorbidities have been linked to a host of adverse functional outcomes, such as increased suicide attempts, drug abuse, and failure to adhere to ARV medications. Differentiating neuropsychiatric features of HIV infection from pre-existing symptoms is particularly important for healthcare providers involved in making diagnostic decisions and treatment recommendations. The following chapter reviews historical and current literature on psychiatric disturbances commonly associated with HIV, with emphasis on assessment. We also provide a brief review of treatments, including non-pharmacological evidence-based treatments.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Psychiatric comorbidities

- Neuropsychiatric features

- HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder

- Mood disorders

- Severe mental illness

- Substance abuse

-

1.

Psychiatric comorbidities place individuals at risk for HIV infection and transmission.

-

2.

Clinicians need to distinguish between pre-existing psychiatric disorders and CNS manifestations of HIV infection.

-

3.

Treatment of comorbid psychiatric disorders is important for HIV-related outcomes.

-

4.

Non-pharmacological interventions have shown promise for treatment of psychiatric disorders in HIV-infected persons

12.1 Introduction: HIV Psychiatry

The shift in public knowledge, concern, and attention to the HIV epidemic has resulted in a number of efforts toward prevention that include early screening, public distributions of condoms, and community needle exchange programs [1] https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_nhas.pdf. For those recently diagnosed, there are a growing number of “linkages to, retention in, and re-engagement in HIV care” (LRC) programs [2]. For LRCs, entering and staying in care are pivotal in the care continuum, which begins with the diagnosis of HIV infection, entry into, and retention in HIV medical care, access, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and viral load suppression.

Psychiatric comorbidities pose considerable challenges to the success of these intervention efforts. For example, risk reduction interventions assume that the individual has the capacity to make informed decisions about his or her behavior (e.g., engaging in risky sex). Interventions that use contingency management principles (i.e., the use of proximal awards for positive behavior change) assume that the patient has intact cognitive/neural reward systems. Among individuals with psychiatric illness, cognitive resources may be grossly limited and even further compromised in the context of HIV infection (see [3,4,5,6,7]).

In primary care settings , psychiatric disorders are often under-detected, misdiagnosed, undertreated, or treated improperly. Psychiatric disorders are more common in the HIV-seropositive population (~63%) as compared with the HIV-seronegative population (~30.5%) [8, 9]; therefore, the need for psychiatric presence in HIV care settings has become increasingly recognized [10]. Psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depression and substance abuse, are one of the most consistent barriers cited for nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Findings also support that depression and recreational drug use contribute to continuous engagement in high-risk sexual behavior [18,19,20].

Early in the epidemic, a substantial majority of HIV-infected persons presenting for intake to an HIV primary care clinic suffered from depression, substance dependence, or another current psychiatric disorder; however, clinicians failed to identify most cases [21]. Similarly, population-based studies have found that individuals meeting the criteria for major depression are commonly undiagnosed and untreated [22, 23]. A more recent study examined attrition across four stages of care : (1) clinical recognition of depression, (2) treatment of depression, (3) adequacy of treatment, and (4) treatment response [24]. They estimated that among individuals with HIV, only 45% of individuals meeting the criteria for depression were clinically recognized; only 40% of recognized cases received treatment, only 40% of patients treated are treated according to standard guidelines, and only 70% of patients receiving adequate treatment achieve remission. This data suggested that among HIV individuals with depression, only 18% receive treatment, and only 5% achieve remission, which indicates that identifying and treating depression remain a problem. This is particularly concerning due to the fact that a majority (72%) of depressed HIV patients should achieve remission if properly identified and treated [25]. Toward this end, screening tools for depression (e.g., PHQ-9) have been evaluated for feasibility and show considerable promise for use within busy outpatient clinics [26, 27]. Nevertheless, more work is needed to fully understand the manifestations of psychiatric symptomatology and fluctuations throughout the course of the disease.

As such, it is foreseeable that psychiatric screenings and assessments will be a major component of HIV clinical care, if not at the forefront. Screening for mood disorders, anxiety, and psychosis in HIV-infected people is crucial because of the downstream impact of mental health on HIV-related health outcomes. Clinicians will need to be able to recognize psychiatric conditions that place individuals at risk for HIV or for worsening of HIV (if already diagnosed) versus those that occur secondary to infection or treatment. This is no easy task given that psychiatric symptoms may manifest for a number of reasons including psychosocial stressors, medication side effects, neuroinflammation, and immune system complications (e.g., reduction in CD4 count, rise in viral load, or onset of brain infection – for a review, see [28, 29]). Once a psychiatric diagnosis is made, it is necessary to determine appropriate treatment – whether that is in the form of pharmacotherapy, behavioral or psychotherapy, or combined treatment.

12.1.1 History of HIV Psychiatry

Loewenstein and Sharfstein [30] were among the first to describe the clinical sequelae of psychiatric disorders in seven AIDS patients referred for consultation. These cases were identified as having organic neurologic disease, which included central nervous system (CNS ) cytomegalovirus (CMV ) infection, cryptococcal meningitis, and disseminated lymphoma. Subsequently, Hoffman [31] reported two AIDS patients with organic mental disorder, one with progressive dementia and one with severe delirium. Although the exact etiology was unknown, both patients shared similar clinical presentations [32]. Behaviorally, patients presented with fluctuations in sensorium, behavioral responses, speech, and cognitive processes, which did not correlate well with any objective factors such as normal EEG findings. These findings suggested that organic brain dysfunction should be considered despite normal EEG findings [31]. Following these observations, several studies described cases of clinical syndromes that included affective symptoms [33], delusions [34], and features of dementia [35] that were attributed to infection of the CNS.

12.2 Psychiatric Disorders Before Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (i.e., Pre-HAART )

Pre-HAART studies vary in the reported prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, though most studies agree that the rates of psychiatric disorders are higher among individuals diagnosed with HIV/AIDS than in the general population. Differences in the reported rates of psychiatric disturbance may be attributed to the use of convenience samples as well as differences in clinical severity. Notably, some earlier reports used patients who had met the criteria for AIDS, whereas others used patients who were identified as HIV seropositive but had not yet advanced to AIDS. Studies generally reported a higher rate of mood disturbance among patients diagnosed with HIV and/or AIDS [36,37,38], and rates increased even further when factoring in the history of intravenous drug use [38]. In the same study, a diagnosis of depression continued to independently predicted serostatus after factoring in the history of intravenous drug use. An investigation of 60 patients referred to the liaison psychiatric service over the course of 1 year found that the most common reason for referral was affective disorder (58%), adjustment reaction (15%), paranoid states (10%), personality changes (6%), and schizophrenia (3%) [39]. In this same study, 23 patients underwent CT scan, and of those, 17 showed brain abnormalities. Walkup and colleagues [40] found that 5.7% of persons listed on the New Jersey HIV-AIDS registry had received a diagnosis of schizophrenia, which is much higher than the national prevalence rate of 1.1%. They also found that 6.8% of persons on the registry had received a diagnosis of a major affective disorder, for a total of 12.5% with a serious mental illness.

In contrast to the aforementioned studies, Bialer and colleagues [41] did not report a higher rate of mood disturbance among AIDS patients in their large-scale investigation of patients who were referred for inpatient psychiatric consultation at Beth Israel Medical Center. Rather, they reported an increased prevalence of dementia among persons with AIDS in comparison with non-HIV patients, whereas substance use disorder and personality disorders were more likely to be found among HIV-seropositive patients in comparison with persons with AIDS. For many of the earlier studies, concerns have been raised that HIV-induced organic mood disorders were misdiagnosed as functional depression [36, 42,43,44,45], as data suggest that the two entities generally have different clinical manifestations. Early studies failed to find that depression was related to markers of neurologic compromise such as cognitive impairment [46, 47]. In fact, a common clinical impression was that individuals who seemed the most depressed and anxious would perform well on neurocognitive testing, whereas others who were calm and showed normal affect (possibly reflecting a lack of awareness) would show impairments in cognitive functioning [46]. Thus, features such as apathy, withdrawal, mental slowing, and avoidance of complex tasks associated with early HIV-induced organic mental disorders may be differentiated clinically from low self-esteem, irrational guilt, and other psychological features of depression. Collectively, these studies highlight the relationship between clinical severity and the prevalence of mood disturbance and the importance of identifying an organic etiology.

12.3 Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in the HAART Era

The advent of HAART has transformed HIV from a fatal disease to a manageable chronic illness. This was achieved through restoration of the immune system that allowed patients protection against opportunistic infections [48,49,50,51]. However, neurological deficits and cognitive disorders were still found to persist or progress in some patients with treatable infections [52]; therefore, the benefits of HAART on HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders were not as clear at the time [53].

The HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study (HCSUS ; [54]) examined mental health and substance use in a large, nationally representative sample of adults receiving care for HIV in the USA. Study participants were administered a brief instrument that screened for mental health disorders and drug use during the previous 12 months. Approximately 50% of the sample screened positive for a mental health disorder, primarily major depression (approximately 1/3 of the sample) and dysthymia (approximately 1/4 of the sample). These rates were similar to those reported in pre-HAART. Nearly 40% reported using an illicit drug other than marijuana, and 12% screened positive for drug dependence. Physicians from the Moore Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital [55] reported that more than half of the patients seeking HIV medical care have a major psychiatric disorder other than substance abuse or personality disorders, with approximately 20% with cognitive impairment [56].

Since these reports, there has been a demographic shift in the HIV population. Changing from a disease that once targeted homosexual, white men from middle-class communities, new infections are highest among people of color, in women, and in low-resourced communities. Although the majority of people currently living with HIV in the USA are men who have sex with men (MSM), heterosexual transmission accounted for 27% of all newly diagnosed AIDS cases in 2009 – which is approximately ten times the rate reported in 1985 [57]. In the USA, the rates of HIV among injecting drug users (IDU ) has decreased significantly over time. In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that about 9% of the 50,000 of annual new infections in 2011 were among IDUs. Women of color are a subgroup that is particularly affected.

HIV tends to be concentrated in highly vulnerable, marginalized, and stigmatized populations such as ethnic/racial minority populations. Racial/ethnic minorities are particularly vulnerable to aquiring HIV-infection, as this group is more likely to live in poverty, report histories of abuse and incarceration, and have social networks that place them at risk for both HIV and mental health problems. In 2010, African-Americans accounted for 50% of all AIDS cases diagnosed during the year, even though they accounted for only 12% of the population. Among African-American women, the figures are even more alarming – representing up to 72% of all new HIV cases in American women [57]. African-American/Black women accounted for two-thirds (64%) of new AIDS diagnoses among women in 2010; Latinas represented 17% and white women 15%. As such, cultural considerations in the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders are also critical for HIV care among these demographic subgroups.

12.4 Psychiatric Disorders and Risk for HIV Infection and HIV Transmission

As mentioned throughout this chapter, pre-existing psychiatric disorders are common in HIV infection and must be distinguished from those that occur secondary to infection. A number of psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders, are associated with increased risk of HIV/AIDS and interfere with treatment [12]. Data from 645 South Africans who participated in a community-based study demonstrated that 33% reported depression, 17% reported alcohol abuse, and 15% reported post-traumatic stress disorder. After adjusting for demographic characteristics, the presence of any of these three conditions was strongly associated with HIV risks, which included forced sex and transactional sex [58]. When identifying patients who are at risk for contracting HIV, clinicians should consider that patients with substance use disorders, patients with severe mental illness, and victims of sexual abuse/crimes have specific risks for becoming infected with HIV. Psychiatric disorders increase risk behaviors such as sexual contact with multiple partners, injecting drug use, and unsafe sex practices [59]. For example, in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study [60], the proportion of gay and bisexual men reporting the use of an illegal drug in the prior 6 months ranged from 92% to 55%, between 1985 and 1989. Among HIV-negative psychiatric patients, nonadherence ranges between 28–52% for major depressive disorder and 20–50% for bipolar disorder. A recent investigation found that loss of a loved one has consistently been associated with various health risks. Little is however known about its relation to STIs . A large population-based study of women from the Swedish Multi-Generation Register found that women who had experienced bereavement were at significantly higher risk for all of the STIs studied [61].

12.5 Comorbid Conditions

Comorbid mental illness among HIV-infected individuals in the USA is substantially higher than in the general population, with rates ranging between 5% and 23%, compared with a range of 0.3%–0.4% among the general population [62]. Mood disorders can result in the most adverse outcomes, as patients with mood disorders are at greater risk for suicide and failure to adhere to medications. Some studies suggest that depressive and anxiety comorbidities accelerate HIV disease progression [63,64,65,66], which may be mediated by such factors as changes in medication adherence [67] and lack of health-promoting behaviors [68]. A meta-analytic review of studies conducted in South Africa and other sub-Saharan African countries reported similar findings with respect to higher prevalence rates among those with HIV/AIDS, although the range in prevalence is large across studies (from 5% to 83%), which may result from differences in tools and populations studied [69]. In a study of an HIV-infected sub-Saharan population , [70] there was a substantial prevalence of both major depression (35%) and post-traumatic stress disorder (15%). In another investigation of individuals in South Africa, the prevalence of depression, PTSD, and alcohol dependence/abuse was 14%, 5%, and 7%, respectively [71]. Similar to US findings, studies of HIV+ individuals with late-stage disease found that common mental disorders such as depression tended to increase, while the use of HAART was shown in one study to improve general mental health [72,73,74] (Table 12.1).

12.5.1 Major Depressive Disorder (MDD )

A diagnosis of major depressive disorder is made when five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning: (1) depressed mood most of the day (nearly everyday), (2) markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities, (3) significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain or decrease or increase in appetite nearly everyday, (4) insomnia or hypersomnia, (5) psychomotor agitation or retardation, (6) fatigue or loss of energy nearly everyday, (7) feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt, (8) diminished ability to think or concentrate or indecisiveness, and (9) recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempt or plan [75].

Studies have found significant relationships between depression and mortality in HIV-infected individuals [76,77,78], whereas others have not [79, 80]. For example, in the San Francisco Men’s Health Study , a 9-year longitudinal study of HIV-seropositive men, higher levels of depression at the beginning of the study were associated with faster progression to AIDS [81]. In another study, involving 414 HIV-infected gay men studied over 5 years, baseline depression was associated with shorter time to death but not change in CD4+ count or progression to AIDS [78]. An analysis of 1809 gay men from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study found no relationship between depression measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD) at study entry and progression of HIV infection during 8 years of follow-up [80]. Disease progression was defined as time to AIDS, death, or decline in CD4+ T lymphocytes . In later analyses of these data, the authors found that self-reported depressive symptoms appeared to rise during the 1.5 years before an AIDS diagnosis [82]. The authors interpret these findings as an indication that depression may increase toward the later stages of HIV infection and thus may be a manifestation of the disease process. While diagnosing depression uses standard criteria for all populations, certain symptoms may be more prevalent in individuals with HIV thereby obscuring clinical assessment of depression. Specifically, appetite and sleep disturbances are more frequently reported in HIV-seropositive patients as compared to HIV-seronegative patients [83]. Demoralization can be difficult to distinguish from major depression, but there are distinctive features between the two syndromes. Depression is characterized by persistent anhedonia, and demoralization is being often characterized by helplessness and linked to recent events or ongoing life circumstances [84,85,86]. Patients with major depression respond relatively well to antidepressant medications; those with demoralization tend to respond well to psychotherapy and not to medications [87, 88].

The diagnosis of comorbid MDD in HIV-infected persons may be difficult, because the neurovegetative symptoms of premorbid MDD (such as lack of energy, fatigue, anorexia, and sleep disturbances) may also be caused by the biological effects of HIV [89]. HIV infection stimulates increasing levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6, interleukin-1-beta, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interferon-gamma [90,91,92], which are associated with sickness behavior (fever, hypersomnia, anorexia, decreased motor activity, and loss of interest in the environment). In differentiating between pre-existing MDD and the neurovegetative symptoms of HIV, it may be useful to remove the somatic depression symptoms included in diagnostic instruments such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the CESD. Indeed, studies have found that removing somatic subsets of depression symptoms improved the clinical utility of the BDI and CESD [83, 93].

Chronic stressors associated with HIV infection may exacerbate mood disorders. Studies have documented dysregulation of the HPA axis and blunted adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH ) responses among HIV-infected individuals [78]; thus, it is plausible to expect that HIV status may increase vulnerability to depression HPA-axis dysregulation. Several studies have reported that HIV-seropositive individuals with a major depressive episode or self-reporting depressed mood on standard instruments may demonstrate reduced performance than non-depressed individuals in some cognitive domains (e.g., memory tasks) or report more cognitive complaints [94,95,96]. However, none of these studies reported an association with neurocognitive impairment. In contrast, others studies have suggested a possible link between increased depressive complaints and lower cognitive function [93, 97, 98]. A longitudinal study of 227 HIV-positive adult men who did not meet the criteria for a current major depressive episode at baseline reported no neurocognitive performance differences in association with lifetime or incident depression and suggested that neurocognitive impairment and major depression be considered two independent processes [99].

HIV-infected individuals who are at greatest risk for developing depression are those with a history of depression, homosexual men, women, or intravenous drug users (IVDUs [100]). Other risk factors associated with developing major depression in HIV-seropositive persons include social stigmatization, isolation, lack of social support, death of friends as a result of HIV/AIDS, and gender [101, 102]. In a longitudinal study of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected men, lifetime prevalence of major depression or other psychiatric disorders did not differ between the groups. However, at 2-year follow-up, those with symptomatic HIV disease were significantly more likely to experience a major depressive episode than individuals who were either in the HIV asymptomatic or control group. However, HIV disease progression did not predict the presence of neurocognitive impairment [103].

Differential diagnosis in a patient with a complaint of depression includes (1) major depression and related mood; (2) demoralization and grief states related to the losses and stresses associated with HIV; (3) delirium, a waxing and waning mental state associated with global cerebral dysfunction and possibly disease acceleration; and (4) dementia, including AIDS dementia and other forms of subcortical damage.

12.5.2 Apathy and Irritability

Apathy (a loss of goal-directed behavior and motivation) and irritability are common neuropsychiatric features of HIV [104, 105]. Approximately 26% of HIV-seropositive individuals meet the criteria for clinically significant apathy, and multiple studies have shown both apathy and irritability to be more common/severe relative to HIV-seronegative controls [104,105,106]. The clinical importance of apathy has been debated [107, 108]. Nevertheless, within the HIV population, apathy is related to some meaningful outcomes, such as medication adherence [14], but only minimally related to other meaningful outcomes, such as quality of life [106]. We are unaware of any studies or clinical trials examining treatments of apathy in HIV. In general, treatment of apathy in other populations (such as Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s disease) has not been promising, and findings have been inconsistent regarding the superiority of medications over placebo (for review, see Drijgers [109]). Future investigations of treatments for apathy may be particularly important as pathophysiology of apathy may dramatically differ from other common mood disorders, such as depression. In fact, Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) , a common treatment for depression, may be related to worsening of apathy [110]. Investigations into non-pharmacological treatments for apathy, such as behavioral activations, are also warranted.

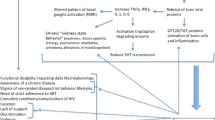

Apathy and irritability are of particular interest in HIV because they are thought to reflect disruption of the central nervous system (CNS ). In contrast other psychiatric symptoms (such as depression and anxiety) are less related to a neurologic insult and may reflect adjustment to social, medical, or financial stressors [104]. Although symptoms of apathy and depression may overlap, apathy has been shown to be a unique construct, separate from depression [106, 111]. The high occurrence of apathy and irritability is thought to be related to disruption of frontal-subcortical networks important for initiation and monitoring of behavior [112]. Indeed, neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies have found support for apathy and irritability reflecting CNS disruption [113]. Frontal-subcortical networks are known to be an important mechanism for executive functioning. Among HIV-infected individuals, apathy and irritability, but not depression or anxiety, are associated with impairments in executive functioning [104, 105]. Studies using diffusion tensor imaging have shown that white matter tracts subserving the medial prefrontal cortex (an area important for motivation and goal-directed behavior) are less intact in HIV-infected individuals relative to HIV-uninfected controls [114,115,116,117]. White matter integrity in these regions was related to the severity of apathy in a study of HIV-infected individuals [114]. A similar study found the relationship between apathy and white matter integrity to be independent of depression and to be stronger among individuals with more severe HIV (lower CD4 counts). Such findings support that apathy may be a syndrome that arises from HIV-associated frontal-subcortical disruption.

12.5.3 Mania

HIV-infected patients with secondary mania, termed “HIV mania ,” may present as agitated, disruptive, sleepless, having high levels of energy, and being excessively talkative [89]. They have a high rate of psychotic symptoms such as auditory or visual hallucinations and paranoia. HIV mania is reported to be associated with irritability rather than euphoria. Unlike primary mania, cognitive deficits are usually present. Mania occurring in the early stages of HIV infection may represent bipolar disorder in its manic phase, whereas mania in persons with AIDS is secondary mania linked to the pathophysiology of HIV brain infection [118].

A first episode of HIV mania typically occurs in the context of a CNS disorder, such as CNS opportunistic infection (OI). The mechanisms are poorly understood; however, the HIV nef protein is reported to alter CNS dopamine metabolism leading to hyperactive, manic-like behaviors in animal models [119]. Reports of HIV mania have decreased coincidently with the widespread use of ART [120], but it remains a problem among untreated and undertreated persons [121]. The differential diagnosis of brain disorders underlying suspected HIV mania includes substance use (especially stimulants), alcohol withdrawal, metabolic abnormalities (e.g., hyperthyroidism), and CNS OI. Evaluations should include a neurologic and mental status examination, brain MRI scan with and without contrast, serology for syphilis, urine toxicology, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination (if medically safe), including tests for OI and a quantitative HIV CSF polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (viral load in CSF) [89]. HIV+ patients with comorbid bipolar disorder are less likely to be adherent to antiretroviral and psychiatric medications [122]. Therefore, promoting adherence in this subgroup is critical in protecting against poor HIV outcomes.

12.5.4 Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders include disorders that elicit fear, anxiety, and behavioral disturbances. Anxiety disorders include mild adjustment disorders, panic disorder, phobias, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, acute stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. The prevalence of anxiety disorders in the HIV populations ranges from about 25% to 40%. Manifestations of anxiety disorders, such as adjustment disorder, are more prevalent at diagnosis and during new treatment or acute illness [123]. It is important to recognize and treat anxiety disorders in the HIV-positive population. Increased rates of anxiety disorders are associated with treatment dropout, high-risk behaviors, and suicide. While the rates of anxiety disorders in the HIV population are generally similar to those of the general population, one of the more common anxiety disorders that disproportionately affect HIV patients is post-traumatic stress disorder. An assessment of an HIV-infected patient presenting with symptoms of anxiety disorder should first evaluate a patient’s recent medication and substance use history (especially stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine), previous psychiatric history, and sleep patterns. Because most anxiety disorders appear in adolescence or young adulthood, patients will often have a history of symptoms predating HIV [124].

12.5.5 Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

A diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder is made when the following criteria are met: (1) exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence; (2) presence of one (or more) intrusion symptoms associated with the event, (3) persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning after its occurrence; and (4) negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event(s) [75]. Rates of PTSD have been found to range anywhere from 22% to 64% and tend to be higher among marginalized and stigmatized populations, such as ethnic/racial minorities, homosexuals, and low-income. Symptoms associated with PTSD include intrusive memories, avoidance of trauma reminders, numbness, hyper-arousal, and experiencing distorted or negative thoughts about oneself [75]. PTSD comorbidity among HIV+ individuals is prevalent among individuals with histories of early trauma and stress [125,126,127] and has been hypothesized to be linked to HIV-related neurobiological alterations which may render the system more vulnerable to stress (for review, see Neigh [128]). PTSD predicts worse HIV-related outcomes for both women [129, 130] and men [131]. While the research is correlational in nature, studies have suggested that individuals with PTSD have a more negative course and progression of HIV/AIDS, continue to use drugs, and have altered immune levels. It has been found in some studies (although not all) that HIV-positive individuals who have been exposed to a traumatic event show a more rapid decrease in CD4+/CD8+ cell ratios as compared to HIV-positive individuals without a trauma history. A recent study of virologically suppressed HIV-infected patients found that those with PTSD had significantly higher total white blood cell counts, absolute neutrophil count, CD8%, and memory CD8%, lower naïve CD8%, and higher rate of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein than participants without PTSD [132]. In one study of HIV risk behaviors, PTSD was associated with increased HIV risk behavior, whereas depression was associated with increased condom use [58]. Elevated stress and emotional reactivity have been linked to increased sexual transmission risk behaviors [133, 134].

12.5.6 Substance Use Disorders

Substance use disorders are characterized by a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms indicating that the individual continues use despite significant consequences related to use. Drug use, especially the injection of drugs, has been associated with poor HIV-related outcomes. HIV-infected drug users have increased prevalence and frequency of medical, psychiatric, and substance use disorders that increase morbidity and mortality compared with age-matched HIV-infected non-users [135]. The number and range of these comorbid disorders complicate diagnosis and treatment, resulting in several challenges in the provision of comprehensive care. Injection drug use has been found to be highly prevalent among individuals with a psychiatric disorder, particularly mood disorders [136]. Studies of heroin users have documented elevated rates of major affective and anxiety disorders including PTSD [137, 138]. While injection drug use is a more direct route of HIV transmission, other substances such as alcohol can place individuals at risk for infection. For example, rates of injection drug use are high among alcoholics in treatment [139, 140].

Alcohol use disorders are common in people living with HIV/AIDS and in IDUs. Heavy alcohol use increases risk of HIV transmission to others [141], decreases retention in care [142], decreases treatment adherence [143, 144], increases HIV risk behaviors [145,146,147], and decreases likelihood of suppression of HIV [148, 149]. Earlier studies reported that individuals with a history of heavy alcohol use are more likely to report engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors, including multiple sex partners, unprotected intercourse, sex with high-risk partners (e.g., injection drug users, prostitutes), and the exchange of sex for money or drugs [139, 140]. According to McKirnan and Peterson [150], alcohol use may be used as an excuse for engaging in socially unacceptable behavior or to reduce conscious awareness of risk. This practice may be especially common among men who have sex with men. Treatment of alcohol abuse has the potential to positively affect HIV treatment outcomes and reduce HIV transmission.

Across studies conducted in South African and other sub-Saharan African countries, it was found that problem drinkers were more likely to be men, to engage in more risky sexual practices, and have a more frequent history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs ) [151, 152]. Kalichman et al. [153] found that alcohol use in the context of a sexual encounter partially mediated the relationship between sensation seeking and HIV risk. In a study that compared a skills building and HIV risk reduction counseling session with didactic HIV-educational/control intervention, effects of increased condom use and decreased drinking prior to sex was found at 3-month but not 6-month follow-up, suggesting that the positive effects of behavioral risk reduction among problematic users may be time limited [154].

Contrary to popular belief, crack cocaine was not always considered a risk factor for HIV acquisition and transmission. In 1988, researchers in New York City suggested the adoption of crack smoking, in lieu of intravenous cocaine use, as a mechanism of AIDS risk reduction [155, 156]. However, a series of studies followed which indicated that when compared with intravenous drug users, crack smokers may be at equal or greater risk for HIV and other STD infections [157,158,159,160]. Methamphetamine (METH) use has been found to be associated with nonadherence [122, 161,162,163]. In a study of HIV+ individuals with and without a lifetime history of METH use and comorbid antisocial personality disorder (ASPD ), major depressive disorder (MDD ), and attention deficit disorder (ADD ), results indicated that co-occurring ADD, ASPD , and MDD predicted ART nonadherence. Current METH use regardless of comorbidity was significantly associated with lower adherence [122].

Although the use of marijuana is more common among individuals with HIV relative to the general population, very few studies have examined the relationship between marijuana and HIV-related outcomes or risk. Specifically, 23–56% of individuals with HIV reported using marijuana in the last month of the survey period compared to 8.4% of the general population [164, 165] (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration , 2011). Individuals with HIV report they use marijuana to reduce anxiety/depression, to increase appetite and weight gain, and to treat pain [164]. In contrast, marijuana has been associated with negative outcomes such as cognitive impairment and lower adherence to ART, relative to non-marijuana-using HIV patients [166, 167]. Similarly, marijuana use has been found to be associated with unprotected sexual intercourse [168, 169] as well as STD infection [170]. However, these relationships tend to be moderated by such factors as HIV severity and amount of marijuana use. For example, Cristiani and colleagues [166] found that marijuana use was associated with cognitive impairment among symptomatic HIV participants but to a lesser extent among asymptomatic HIV participants . Regarding ART adherence, lower adherence, higher viral load, and more severe self-report symptoms of HIV/medication side effects were reported among individuals with HIV who met the criteria for cannabis dependence, but not casual/nondependent marijuana users. In addition, marijuana is also related to risk of contracting HIV, particularly for young adolescents [168].

12.5.7 Severe Mental Illness (SMI )

In a meta-analytic study of 52 studies, the majority of adults with SMI were sexually active, and many engaged in risk behaviors associated with HIV transmission (e.g., unprotected intercourse, multiple partners, injection drug use) [19]. HIV risk behaviors were correlated with factors from the following domains: psychiatric illness, substance use, childhood abuse, cognitive-behavioral factors, and social relationships. HIV prevention efforts targeting adults with SMI must occur on multiple levels (e.g., individual, group, community, structural/policy), address several domains of influence (e.g., psychiatric illness, trauma history, social relationships), and be integrated into existing services (e.g., psychotherapy, substance abuse treatment, housing programs) [19, 20]. While epidemiological evidence suggests that individuals with severe mental illness are more likely to live in risky environments that make them vulnerable to HIV [171, 172], the findings are mixed with regard to the link between HIV risk and psychotic-spectrum disorders, with many reporting small associations [173]. In a study by Carey et al. [173] that reviewed records of 889 patients with mental illness, it was found that only 11% reported HIV risk behavior. They found no direct association between psychiatric disorder and risky sex. In a follow-up study, 1558 records were reviewed and the numbers increased to approximately 23% [171]; however, risk behavior was less common among patients diagnosed with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. Similarly, in a study of 228 female and 202 male outpatients (66% mood disorder, 34% schizophrenia), it was found that risk behavior was more frequent among patients diagnosed with a mood disorder (compared to those diagnosed with schizophrenia) and/or with a substance use disorder (compared to those without a comorbid disorder).

12.5.8 Personality Disorders

Personality disorders (PD) are diagnosed if there is a pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture. The pattern is manifested in two (or more) of the following areas: (1) cognition, (2) affectivity, (3) interpersonal functioning, and (4) impulse control. The pattern must be inflexible and pervasive across many personal and social situations as well as lead to significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning [174]. Personality disorders that fall under the cluster B category of personality disorders (i.e., antisocial personality disorder (ASPD ), borderline personality disorder (BPD ), histrionic personality disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder) have been the most reliably associated with risk-related behaviors and outcomes in HIV. The literature supports a higher rate of PD in HIV-positive individuals, in particular BPD and ASPD . ASPD is characterized by a pattern of irresponsible, impulsive, and remorseless behaviors beginning in childhood or early adolescence and continuing into adulthood. ASPD is highly prevalent among drug abusers [175,176,177]. ASPD participants reported higher rates of IVDU, frequency of needle sharing, and a number of equipment-sharing partners and lower rates of needle cleaning [178,179,180,181].

In a randomized HIV prevention study, Compton and colleagues [182] compared the effectiveness of standard HIV testing and counseling protocol to a four-session, peer-delivered, educational intervention for out-of-treatment cocaine users with and without ASPD and major depression. While all groups, regardless of assignment to standard vs. peer-delivered intervention or psychiatric status, improved significantly in outcomes of crack cocaine use, injection drug use, and number of IDU sex partners and overall number of sex partners, ASPD was associated with significantly less improvement in crack cocaine use and less improvement in having multiple sex partners and having IDU sex partners. Personality disorders are the most unreliably diagnosed out of all the psychiatric disorders, and it becomes more challenging when diagnosing BPD in the context of culture. Symptoms related to unstable self-image, impulsive substance abuse, and mood instability due to societal stigma and pressures may be the norm within certain cultures. For example, adolescents and young adults with identity problems may display transient behaviors that appear like BPD . Hence, clinicians should be cognizant to conduct thorough assessments when considering a PD diagnosis.

12.6 Psychiatric Assessment and Treatment

Central to conducting a psychiatric assessment of the HIV/AIDS patient is an adequate fund of knowledge about the pathophysiology and virology of HIV, epidemiology of HIV/AIDS, transmission of HIV, pathogenesis, staging of HIV disease, HIV treatment, and HIV effects on the central nervous system. The clinician should be prepared and well versed in a wide range of assessment tools and skills such as structured interviews, comprehensive diagnostic evaluations, and medical work-ups to rule out or consider new-onset symptoms [89]. Clinicians should also be aware of cultural and linguistic differences that may influence self-reporting of mental health problems, stigmas associated with both HIV and mental health problems, and social support networks. According to the guidelines set forth by the American Psychiatric Association Working Group on HIV/AIDS [183], (shown in Table 12.2), the clinician must be able to:

The development of a psychiatric treatment plan for patients with HIV infection requires a holistic approach accounting for the biopsychosocial context. Upon first diagnosis and throughout the course of the illness, there may be signs of bereavement and grief with various physical changes as well as the anticipatory loss of life [88]. The symptoms of bereavement (i.e., sadness, insomnia, poor appetite, and weight loss) overlap considerably with depression. Diagnostic decisions must follow a standard diagnostic practice, without minimizing or misattributing symptoms to the burden of having HIV. Depressed patients may also overstate their cognitive and functional limitations. A study by our group compared subjective complaints to actual cognitive and functional performance and found that “over-reporters” – those who presented with complaints regarding cognitive function and performance on daily tasks (e.g., managing medications) but who performed normal on objective measures of function – exhibited higher levels of depressive symptoms compared to those whose self-reports matched their actual performance [184]. On the other hand, clinicians must caution not to quickly diagnosis a mood disorder without consideration of the context. It is common for patients to present with symptoms that mimic a major depressive episode or anxiety disorder shortly after learning about their HIV diagnosis. Usually these symptoms will subside over time as the patient begins to adjust to their illness.

The symptoms of major depression can be masked by symptoms that accompany other HIV-related illnesses. Overlapping symptoms include fatigue, sleep and appetite disturbance, general malaise, and feelings of illness. One study by Pugh and colleagues [185] found no difference in symptoms of fatigue, insomnia, or cognitive dysfunction between early-stage HIV-infected homosexual men and uninfected homosexual controls. When these symptoms do occur in early-stage HIV infection, they are more likely to result from mood disturbance than HIV disease progression. Additionally, increased fatigue and insomnia at 6-month follow-up were highly correlated with worsening of depression but not CD4 count, change in CD4 count, or disease progression by CDC category.

12.6.1 Treatments

Extensive reviews of various types of pharmacological treatments for psychiatric disorders in HIV patients can be found elsewhere [186,187,188]. However, we would be remiss not to provide a brief overview of the various treatments for the more common comorbid psychiatric disorders. Treating psychiatric illness among individuals with HIV infection is frequently complicated by concurrent HAART regimens. The clinician must closely monitor drug-drug interaction and be alert to potential side effects and metabolizing profiles.

12.6.1.1 Antidepressants (Standard and Alternative)

As with treating depression among individuals without HIV, antidepressant medications are commonly used for treatment. In the early epidemic, tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) medications were often used [189, 190] with demonstrated efficacy. However, because of the high rates of negative side effects and concerns of lethality attributed to the use of TCAs, clinicians started to use SSRIs for treating depression [188]. SSRIs are now the most widely used antidepressant treatment for major depression among HIV-infected persons because of their more benign side effect profile and evidence of treatment efficacy [191]. In a study of a 6-week open-label trial with SSRIs, subjects who completed 6 weeks of SSRI treatment experienced significant reductions in both affective and somatic symptoms, which were initially attributed to HIV infection rather than depression [192]. A smaller trial showed no benefit of adding fluoxetine to structured group therapy versus group therapy alone; however, this study was limited by a small sample size of 20 individuals [193]. Another study compared fluoxetine and placebo in depressed patients receiving group psychotherapy [194]. Fluoxetine resulted in a significantly greater percentage of patients (64% vs. 23%) with a reduction in HAM-D score after 7 weeks. This study also showed that patients with mild to moderate depression may benefit from psychotherapy alone, but patients with severe depression did better with a combination of psychotherapy and fluoxetine. Overall, fluoxetine appears to have the most evidence for treating depression in HIV patients, with response rates between 50% and 75%. Limitations of many of the studies include exclusion of patients with active substance abuse and few studies with HIV-infected women.

Psychostimulants have also been used to treat depressive symptoms in patients with advanced HIV, especially when symptoms such as depressed mood, fatigue, and cognitive impairment are present. In a clinical trial’s study of standard and alternative antidepressants among HIV patients with depression, each treatment resulted in significant improvement after both 2 and 6 weeks of treatment according to the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [195].

12.6.1.2 Anxiolytics

SSRIs are the first-line pharmacologic therapy for several anxiety disorders [196] including generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorders, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder in HIV. Specific agents have been approved by the Food and Drugs Administration for each of the major anxiety disorders: generalized anxiety disorder (paroxetine), social phobia (paroxetine), OCD (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine), and PTSD (sertraline). Buspirone has a low abuse potential. It is minimally sedating and has no known withdrawal effects [197]. Buspirone may, however, take up to 4 weeks before producing noticeable therapeutic effects. When a benzodiazepine is required, it is recommended that a low dose is prescribed and used only for short periods of time to minimize, respectively, the risk of abuse and adverse effects (confusion, sedation, cognitive impairment, disinhibition) and interactions with antiretroviral therapy [198].

12.6.1.3 Mood Stabilizers

Lithium, valproic acid, and carbamazepine are effective mood stabilizers in patients with bipolar affective illness. Lithium is the least likely to have specific drug interactions with antiretrovirals [187]. In HIV-infected patients, lithium has the potential to cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tremor, thyroid dysfunction, and kidney problems at therapeutic doses [199]. el-Mallakh [200] described 14 cases and reported that AIDS-associated mania are responsive to lithium but that AIDS patients with associated neurologic and cognitive dysfunction may be more prone to neurocognitive side effects. Valproic acid can cause elevated transaminase levels and severe hepatitis, and it has been recommended that physicians observe liver enzymes periodically [187]. In a retrospective chart review of 11 HIV+ patients with an acute manic episode, Halman [201] found that neuroleptics and anticonvulsants were an effective alternative among those with poor tolerance of lithium. A number of factors must be taken into consideration when prescribing anticonvulsants to HIV+ individuals. Carbamazepine is metabolized via CYP3A4 and induces its own metabolism, increasing metabolism of protease inhibitors [202] and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [203]. Such autoinduction and the potential for bone marrow suppression make its use complicated. There is clinical evidence of carbamazepine toxicity resulting from its use in combination with CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as ritonavir [204].

12.6.1.4 Antipsychotics

Antipsychotic drugs (also called neuroleptics) include both older “typical” drugs and the newer “atypical” (second-generation) medications that are FDA approved for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other psychotic disorders [204]. The typical neuroleptics (characterized by chlorpromazine and haloperidol) are specific dopamine receptor (D2) antagonists. Newer antipsychotics also interact with other receptor families, such as serotonin [187]. Newer antipsychotics are often preferred because of their efficacy in treating psychotic conditions and the decreased frequency of extrapyramidal adverse effects associated with their use. However, significant metabolic adverse effects (like hyperglycemia, weight gain, and hypercholesterolemia) often make newer neuroleptics less appealing. Clozapine, a very effective neuroleptic, has the potential to cause agranulocytosis, necessitating weekly blood count measurements for the first 6 months. In addition, this medicine can cause significant weight gain, orthostasis, sialorrhea, and seizures [199]. Molindone (20–180 mg/d), an atypical antipsychotic, was first reported to be beneficial for HIV-associated psychosis and agitation with minimal side effects [44]. Clozapine has been demonstrated to be effective and generally safe in treating HIV-associated psychosis (including negative symptoms) in patients with prior drug-induced Parkinsonism [205]. Risperidone (mean dose 3.3 mg/d) was reported to be effective in treating HIV-related psychotic and manic symptoms [206]. CYP inhibitors have the potential to increase the concentration of the antipsychotics, clozaril and pimozide. For this reason, these drugs have been contraindicated with antiretrovirals with CYP inhibition, such as ritonavir. In addition, the potential for toxic increases by CYP inhibitors exists in other antipsychotics, including chlorpromazine, haloperidol, olanzapine, and risperidone [207]. Antipsychotics do not generally significantly inhibit or induce P-450 enzymes and can safely be added to HAART regimens without causing toxicity or HAART failure [208]. Another concern with the administration of antipsychotics and antiretrovirals is the overlapping toxicities of metabolic disturbances, primarily with atypical antipsychotics . Metabolic disturbances are seen in 2–36% of patients treated with atypical antipsychotics [209]. In sum, patients with HIV infection are generally very sensitive to medication side effects as they often metabolize drugs more slowly and have compromised blood-brain barrier functioning [208]. Although most patients ultimately tolerate standard doses of most medications, it is advised to start at low doses and slowly increase over time.

12.6.1.5 Behavioral Interventions

For many HIV patients, psychotherapy and psychosocial interventions have been invaluable in the search for meaning during the course of living with HIV [210]. Psychotherapy can be an important intervention to address conditions that may interfere with a patient’s acceptance of HIV illness or their ability to work cooperatively with their healthcare team as well as addressing changes in role definitions and life trajectory as well as treatment adherence challenges.

Non-pharmacological interventions have been used to treat depression and increasing stress management for individuals with HIV. These interventions have consisted both cognitive (i.e., challenging and restructuring automatic negative thoughts) and behavioral approaches (i.e., progressive muscle relaxation), either in combination or separately. Reviews and meta-analyses found these approaches to be effective in terms of improving psychological symptoms (such as depression or anxiety). Additionally, these approaches were effective in improving psychosocial functioning, such as social support, medication adherence, quality of life, and decreasing engagement in risky sexual behaviors [211, 212]. However, there was only limited evidence that improvements in psychological functioning are generalized to improvements in markers’ immunological functioning, such as stress hormones, CD4 counts, or T-cell counts.

Mindfulness-based interventions focus on increasing one’s ability to purposely pay attention in the present moment, without judgment [213]. Mindfulness-based interventions have become a popular research topic within the last decade, but the research is still in its infancy, particularly as it relates to the HIV population. However, preliminary findings are optimistic, as the effect sizes have ranged from medium to small in terms of improvement in positive affect [214]. Perhaps even more impressive, mindfulness-based interventions were found to have a medium-to-large effect size in terms of healthier CD4+ cell counts, relative to HIV+ controls [214, 215]. Future studies are needed in examining the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in terms of other important outcomes, such as medical adherence, risk behaviors, and specific mood symptoms (rather than global affect).

In addition to therapies differing in terms of theoretical orientation, therapies can differ in the modality of administration. A past review found that 95% of intervention using behavioral techniques to improve stress management were delivered in a group format [216]. Although the use of group therapy is beneficial for delivering services to multiple individuals at once, one criticism was that group therapy may not be available/feasible for individuals living in rural or underserved populations. To address this concern, interventions delivered remotely, either over the phone or via the computer, may be of interest. Indeed two recent randomized controls trials found that a cognitive-behavioral therapy and a contingency management program delivered over the phone improved medication adherence among HIV+ individuals [217, 218]. More research focused on delivering psychological services to underserved populations is needed.

Limited research has been conducted in terms of examining other moderators that may be important for psychological therapies. In terms of dosage, one meta-analysis found that interventions consisting of ten or more sessions were more efficacious in improving depressive and anxiety symptoms, relative to interventions consisting of less than ten sessions [212]. A separate study is focused on the efficacy of stress-reduction interventions among different HIV subpopulations, including older adults, women, and individuals with a history of childhood sexual abuse [211]. Although very few intervention studies have focused on these subpopulations, the review has found preliminary evidence for decreased psychological distress and health risk behaviors following stress-reduction management.

12.7 Summary

Comorbid psychiatric features and disorders are important when working with and treating individuals diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. Thus, recognizing predictors of medication adherence among patients with dual psychiatric and substance use disorders is essential for identifying at risk individuals. The presence of pre-HIV psychiatric illness is the strongest predictor of psychiatric diagnosis after knowledge of seropositivity. As discussed throughout this chapter, psychiatric illness from the biological effects of HIV, CNS OI, prescribed medications, or substance abuse can arise. Optimum management of patients at high risk for HIV infection involves a wide range of psychiatric skills: comprehensive diagnostic evaluations, assessment of possible medical causes of new-onset symptoms, and initiation of specific treatment interventions. Early screening and assessment are essential for proper treatment for many persons infected and affected by HIV/AIDS which requires making important distinctions between overlapping symptoms in order to provide accurate diagnoses and treatments.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

Policy WHOoNA (2010) National HIV/AIDS strategy. 23

Control CfD (2016) Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention. Retrieved online from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/

Price RW, Brew B, Sidtis J, Rosenblum M, Scheck AC, Cleary P (1988) The brain in AIDS: central nervous system HIV-1 infection and AIDS dementia complex. Science 239:586–592

Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M et al (2007) Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology 69:1789–1799

Sacktor N, McDermott MP, Marder K, Schifitto G, Selnes OA, McArthur JC et al (2002) HIV-associated cognitive impairment before and after the advent of combination therapy. J Neurovirol 8:136–142

Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Letendre SL, Leblanc S et al (2011) HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol 17:3–16

Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F et al (2010) HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology 75:2087–2096

Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE et al (2005) Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med 352:2515–2523

Tegger MK, Crane HM, Tapia KA, Uldall KK, Holte SE, Kitahata MM (2008) The effect of mental illness, substance use, and treatment for depression on the initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDs 22:233–243

Lyketsos CG, Hanson A, Fishman M, McHugh PR, Treisman GJ (1994) Screening for psychiatric morbidity in a medical outpatient clinic for HIV infection: the need for a psychiatric presence. Int J Psychiatry Med 24:103–113

Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL (2000) Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychol 19:124–133

Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Lam MN et al (2004) Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse. AIDS 18(Suppl 1):S19–S25

Thames AD, Moizel J, Panos SE, Patel SM, Byrd DA, Myers HF et al (2012) Differential predictors of medication adherence in HIV: findings from a sample of African American and Caucasian HIV-positive drug-using adults. AIDS Patient Care STDs 26:621–630

Panos SE, Del Re AC, Thames AD, Arentsen TJ, Patel SM, Castellon SA et al (2014) The impact of neurobehavioral features on medication adherence in HIV: evidence from longitudinal models. AIDS Care 26:79–86

Simoni JM, Frick PA, Huang B (2006) A longitudinal evaluation of a social support model of medication adherence among HIV-positive men and women on antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol 25:74–81

Rao D, Feldman BJ, Fredericksen RJ, Crane PK, Simoni JM, Kitahata MM et al (2012) A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS Behav 16:711–716

Sethi AK, Celentano DD, Gange SJ, Moore RD, Gallant JE (2003) Association between adherence to antiretroviral therapy and human immunodeficiency virus drug resistance. Clin Infect Dis 37:1112–1118

Gomez MF, Klein DA, Sand S, Marconi M, O’Dowd MA (1999) Delivering mental health care to HIV-positive individuals. A comparison of two models. Psychosomatics 40:321–324

Meade CS, Sikkema KJ (2005) HIV risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 25:433–457

Dyer JG, McGuinness TM (2008) Reducing HIV risk among people with serious mental illness. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 46:26–34

Lyketsos CG, Hutton H, Fishman M, Schwartz J, Treisman GJ (1996) Psychiatric morbidity on entry to an HIV primary care clinic. AIDS 10:1033–1039

Asch SM, Kilbourne AM, Gifford AL, Burnam MA, Turner B, Shapiro MF et al (2003) Underdiagnosis of depression in HIV: who are we missing? J Gen Intern Med 18:450–460

Rodkjaer L, Laursen T, Balle N, Sodemann M (2010) Depression in patients with HIV is under-diagnosed: a cross-sectional study in Denmark. HIV Med 11:46–53

Pence BW, O’Donnell JK, Gaynes BN (2012) Falling through the cracks: the gaps between depression prevalence, diagnosis, treatment, and response in HIV care. AIDS 26:656–658

Himelhoch S, Medoff DR (2005) Efficacy of antidepressant medication among HIV-positive individuals with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDs 19:813–822

Crane HM, Lober W, Webster E, Harrington RD, Crane PK, Davis TE et al (2007) Routine collection of patient-reported outcomes in an HIV clinic setting: the first 100 patients. Curr HIV Res 5:109–118

Shacham E, Nurutdinova D, Satyanarayana V, Stamm K, Overton ET (2009) Routine screening for depression: identifying a challenge for successful HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs 23:949–955

Nanni MG, Caruso R, Mitchell AJ, Meggiolaro E, Grassi L (2015) Depression in HIV infected patients: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17:530

Felger JC, Lotrich FE (2013) Inflammatory cytokines in depression: neurobiological mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neuroscience 246:199–229

Loewenstein RJ, Sharfstein SS (1983) Neuropsychiatric aspects of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Int J Psychiatry Med 13:255–260

Hoffman RS (1984) Neuropsychiatric complications of AIDS. Psychosomatics 25:393–395, 399-400

Murphy DA, Roberts KJ, Martin DJ, Marelich W, Hoffman D (2000) Barriers to antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected adults. AIDS Patient Care STDs 14:47–58

Nurnberg HG, Prudic J, Fiori M, Freedman EP (1984) Psychopathology complicating acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Am J Psychiatry 141:95–96

Kermani E, Drob S, Alpert M (1984) Organic brain syndrome in three cases of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Compr Psychiatry 25:294–297

Jacobsen P, Perry SW (1985) Organic mental syndromes possible in AIDS victims. Am J Psychiatry 142:1389

Perry SW, Tross S (1984) Psychiatric problems of AIDS inpatients at the New York Hospital: preliminary report. Public Health Rep 99:200–205

Cournos F, Horwath E, Guido JR, McKinnon K, Hopkins N (1994) HIV-1 infection at two public psychiatric hospitals in New York City. AIDS Care 6:443–452

Silberstein C, Galanter M, Marmor M, Lifshutz H, Krasinski K, Franco H (1994) HIV-1 among inner city dually diagnosed inpatients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 20:101–113

Seth R, Granville-Grossman K, Goldmeier D, Lynch S (1991) Psychiatric illnesses in patients with HIV infection and AIDS referred to the liaison psychiatrist. Br J Psychiatry 159:347–350

Walkup J, Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U (1999) Schizophrenia and major affective disorder among Medicaid recipients with HIV/AIDS in New Jersey. Am J Public Health 89:1101–1103

Bialer PA, Wallack JJ, Prenzlauer SL, Bogdonoff L, Wilets I (1996) Psychiatric comorbidity among hospitalized AIDS patients vs. non-AIDS patients referred for psychiatric consultation. Psychosomatics 37:469–475

Perry SW, Cella DF (1987) Overdiagnosis of depression in the medically ill. Am J Psychiatry 144:125–126

Wolcott DL, Fawzy FI, Pasnau RO (1985) Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and consultation-liaison psychiatry. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 7:280–293

Fernandez F, Holmes VF, Levy JK, Ruiz P (1989) Consultation-liaison psychiatry and HIV-related disorders. Hosp Community Psychiatry 40:146–153

Fernandez F, Ruiz P (1989) Psychiatric aspects of HIV disease. South Med J 82:999–1004

Levin BE, Tomer R, Rey GJ (1992) Cognitive impairments in Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Clin 10:471–485

Hinkin CH, van Gorp WG, Satz P, Weisman JD, Thommes J, Buckingham S (1992) Depressed mood and its relationship to neuropsychological test performance in HIV-1 seropositive individuals. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 14:289–297

Li D, Xu XN (2008) NKT cells in HIV-1 infection. Cell Res 18:817–822

Maschke M, Kastrup O, Esser S, Ross B, Hengge U, Hufnagel A (2000) Incidence and prevalence of neurological disorders associated with HIV since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 69:376–380

Sacktor N, Tarwater PM, Skolasky RL, McArthur JC, Selnes OA, Becker J et al (2001) CSF antiretroviral drug penetrance and the treatment of HIV-associated psychomotor slowing. Neurology 57:542–544

Sacktor N, Lyles RH, Skolasky R, Kleeberger C, Selnes OA, Miller EN et al (2001) HIV-associated neurologic disease incidence changes:: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, 1990-1998. Neurology 56:257–260

Gasnault J, Taoufik Y, Goujard C, Kousignian P, Abbed K, Boue F et al (1999) Prolonged survival without neurological improvement in patients with AIDS-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy on potent combined antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol 5:421–429

Gray F, Chretien F, Vallat-Decouvelaere AV, Scaravilli F (2003) The changing pattern of HIV neuropathology in the HAART era. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 62:429–440

Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS et al (2001) Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58:721–728

Treisman GJ, Angelino AF, Hutton HE (2001) Psychiatric issues in the management of patients with HIV infection. JAMA 286:2857–2864

Treisman G, Fishman M, Lyketsos C, McHugh PR (1994) Evaluation and treatment of psychiatric disorders associated with HIV infection. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis 72:239–250

CDC (2011) Estimates of new HIV infections in the United States, 2006–2009

Smit J, Myer L, Middelkoop K, Seedat S, Wood R, Bekker LG et al (2006) Mental health and sexual risk behaviours in a South African township: a community-based cross-sectional study. Public Health 120:534–542

Sullivan PF, Bulik CM, Forman SD, Mezzich JE (1993) Characteristics of repeat users of a psychiatric emergency service. Hosp Community Psychiatry 44:376–380

Sullivan PF, Becker JT, Dew MA, Penkower L, Detels R, Hoover DR, Kaslow R, Palenicek J, Wesch JE (1993) Longitudinal trends in the use of illicit drugs and alcohol in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Addict Res 1:279–290

Bond E, Lu D, Herweijer E, Sundstrom K, Valdimarsdottir U, Fall K et al (2016) Sexually transmitted infections after bereavement – a population-based cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 16:419

WHO (2008) HIV/AIDS and Ment Health 1–5

Leserman J (2003) HIV disease progression: depression, stress, and possible mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry 54:295–306

Cruess DG, Petitto JM, Leserman J, Douglas SD, Gettes DR, Ten Have TR et al (2003) Depression and HIV infection: impact on immune function and disease progression. CNS Spectr 8:52–58

Antelman G, Kaaya S, Wei R, Mbwambo J, Msamanga GI, Fawzi WW et al (2007) Depressive symptoms increase risk of HIV disease progression and mortality among women in Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 44:470–477

Evans DL, Ten Have TR, Douglas SD, Gettes DR, Morrison M, Chiappini MS et al (2002) Association of depression with viral load, CD8 T lymphocytes, and natural killer cells in women with HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry 159:1752–1759

Leserman J (2008) Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med 70:539–545

Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA (2006) Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS Behav 10:473–482

Breuer E, Myer L, Struthers H, Joska JA (2011) HIV/AIDS and mental health research in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Afr J AIDS Res 10:101–122

Olley BO, Seedat S, Nei DG, Stein DJ (2004) Predictors of major depression in recently diagnosed patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDs 18:481–487

Olley BO, Zeier MD, Seedat S, Stein DJ (2005) Post-traumatic stress disorder among recently diagnosed patients with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Care 17:550–557

Adewuya AO, Afolabi MO, Ola BA, Ogundele OA, Ajibare AO, Oladipo BF (2007) Psychiatric disorders among the HIV-positive population in Nigeria: a control study. J Psychosom Res 63:203–206

Stangl AL, Wamai N, Mermin J, Awor AC, Bunnell RE (2007) Trends and predictors of quality of life among HIV-infected adults taking highly active antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. AIDS Care 19:626–636

Freeman M, Nkomo N, Kafaar Z, Kelly K (2007) Factors associated with prevalence of mental disorder in people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS Care 19:1201–1209

Association AP (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ et al (2001) Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV Epidemiology Research Study. JAMA 285:1466–1474

Cook JA, Grey D, Burke J, Cohen MH, Gurtman AC, Richardson JL et al (2004) Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health 94:1133–1140

Patterson S, Moran, P, Epel E, Sinclair E, Kemeny M, Deeks SG, Bacchetti P, Acree M, Epling L, Kirschbaum C, Hecht FM (2013) Cortisol patterns are associated with T cell activation in HIV. PLOS One. Retrieved online from http://www.plosone.org

Vedhara K, Schifitto G, McDermott M (1999) Disease progression in HIV-positive women with moderate to severe immunosuppression: the role of depression. Dana Consortium on Therapy for HIV Dementia and Related Cognitive Disorders. Behav Med 25:43–47

Lyketsos CG, Hoover DR, Guccione M, Senterfitt W, Dew MA, Wesch J et al (1993) Depressive symptoms as predictors of medical outcomes in HIV infection. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. JAMA 270:2563–2567

Page-Shafer K, Delorenze GN, Satariano WA, Winkelstein W Jr (1996) Comorbidity and survival in HIV-infected men in the San Francisco Men’s Health Survey. Ann Epidemiol 6:420–430

Lyketsos CG, Hoover DR, Guccione M, Dew MA, Wesch J, Bing EG et al (1996) Depressive symptoms over the course of HIV infection before AIDS. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 31:212–219

Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M (2000) Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Nerv Ment Dis 188:662–670

Clarke DM, Kissane DW (2002) Demoralization: its phenomenology and importance. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 36:733–742

de Figueiredo J (2000) Diagnosing demoralization in consultation psychiatry. Psychosomatics 41:449–450

Sansone RA, Sansone LA (2010) Demoralization in patients with medical illness. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 7:42–45

Frank E, Kupfer DJ, Wagner EF, McEachran AB, Cornes C (1991) Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy as a maintenance treatment of recurrent depression. Contributing factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:1053–1059

Chandra PS, Desai G, Ranjan S (2005) HIV & psychiatric disorders. Indian J Med Res 121:451–467

Singer EJ, Thames AD (2016) Neurobehavioral manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS: diagnosis and treatment. Neurol Clin 34:33–53

Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S et al (2006) Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med 12:1365–1371

Breen EC, Rezai AR, Nakajima K, Beall GN, Mitsuyasu RT, Hirano T et al (1990) Infection with HIV is associated with elevated IL-6 levels and production. J Immunol 144:480–484

Stone SF, Price P, Keane NM, Murray RJ, French MA (2002) Levels of IL-6 and soluble IL-6 receptor are increased in HIV patients with a history of immune restoration disease after HAART. HIV Med 3:21–27

Castellon SA, Hardy DJ, Hinkin CH, Satz P, Stenquist PK, van Gorp WG et al (2006) Components of depression in HIV-1 infection: their differential relationship to neurocognitive performance. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 28:420–437

Bornstein RA, Pace P, Rosenberger P, Nasrallah HA, Para MF, Whitacre CC et al (1993) Depression and neuropsychological performance in asymptomatic HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry 150:922–927

Carter SL, Rourke SB, Murji S, Shore D, Rourke BP (2003) Cognitive complaints, depression, medical symptoms, and their association with neuropsychological functioning in HIV infection: a structural equation model analysis. Neuropsychology 17:410–419

Goggin KJ, Zisook S, Heaton RK, Atkinson JH, Marshall S, McCutchan JA et al (1997) Neuropsychological performance of HIV-1 infected men with major depression. HNRC Group. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 3:457–464

Gibbie T, Mijch A, Ellen S, Hoy J, Hutchison C, Wright E et al (2006) Depression and neurocognitive performance in individuals with HIV/AIDS: 2-year follow-up. HIV Med 7:112–121

Braganca M, Palha A (2011) Depression and neurocognitive performance in Portuguese patients infected with HIV. AIDS Behav 15:1879–1887

Cysique LA, Deutsch R, Atkinson JH, Young C, Marcotte TD, Dawson L et al (2007) Incident major depression does not affect neuropsychological functioning in HIV-infected men. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 13:1–11

Giunta B, Hervey W, Klippel C, Obregon D, Robben D, Hartney K, di Ciccone BL, Fernandez F (2013) Psychiatric complications of HIV infection: an overview. Psychiatr Ann 43:199–203

Li L, Lee SJ, Thammawijaya P, Jiraphongsa C, Rotheram-Borus MJ (2009) Stigma, social support, and depression among people living with HIV in Thailand. AIDS Care 21:1007–1013

Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Corwin S, Saunders R, Annang L, Tavakoli A (2010) Relationships between stigma, social support, and depression in HIV-infected African American women living in the rural southeastern United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 21:144–152

Atkinson JH, Heaton RK, Patterson TL, Wolfson T, Deutsch R, Brown SJ et al (2008) Two-year prospective study of major depressive disorder in HIV-infected men. J Affect Disord 108:225–234

Castellon SA, Hinkin CH, Myers HF (2000) Neuropsychiatric disturbance is associated with executive dysfunction in HIV-1 infection. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 6:336–347

Cole MA, Castellon SA, Perkins AC, Ureno OS, Robinet MB, Reinhard MJ et al (2007) Relationship between psychiatric status and frontal-subcortical systems in HIV-infected individuals. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 13:549–554

Tate D, Paul RH, Flanigan TP, Tashima K, Nash J, Adair C et al (2003) The impact of apathy and depression on quality of life in patients infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs 17:115–120

Bogart KR (2011) Is apathy a valid and meaningful symptom or syndrome in Parkinson’s disease? A critical review. Health Psychol 30:386–400

van Reekum R, Stuss DT, Ostrander L (2005) Apathy: why care? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 17:7–19

Drijgers RL, Aalten P, Winogrodzka A, Verhey FR, Leentjens AF (2009) Pharmacological treatment of apathy in neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 28:13–22