Abstract

Women under the age of 40 years and who are at an average risk for breast cancer are not screened for breast cancer but may present with symptoms and are referred to imaging for their breast complaints. Pregnant and lactating women form a unique subset of women in whom imaging is requested for symptoms. Clinical examination and imaging evaluation is a challenge due to physiologic changes in the breast related to pregnancy and lactation. Breast complaints in the pediatric and adolescent age group pose challenges in diagnosis and management. This chapter covers topics related to breast imaging in three specific groups: palpable masses in pediatric and adolescents; benign breast abnormalities in pregnancy and lactation; pregnancy associated breast cancer; breast cancer in young women.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Palpable Breast Masses in the Pediatric and Adolescent Population

The spectrum of abnormalities in the pediatric and adolescents is different from those encountered in older women. Masses may be related to normal or abnormal development of the breast. Breast cancer is exceedingly rare in this age group. Infection, trauma, and cyst formation account for most of the masses prior to puberty and fibroadenoma after [1]. Some of the commonly encountered abnormalities, non-neoplastic and neoplastic, are described next.

Non-neoplastic

Mammary Duct Ectasia

Mammary duct ectasia may occur in infants and be associated with a bloody nipple discharge; associated infection is rare but has been reported [1–3]. Ultrasound demonstrates subareolar ecstatic ducts with debris if infected. Persistent symptoms are rare and if present may require surgical excision [2, 3].

Galactocele

Galactoceles, typically seen in lactating women, may occasionally appear in infants or older boys. Sonographically, these appear as complex cysts, with fat component appearing hyperechoic and water component hypoechoic. Aspiration if performed reveals a milky fluid [1].

Retroareolar Cysts

A mass at the edge of the areola in adolescents may result from obstruction of the glands of Montgomery. These lumps can be painful. Ultrasound may not be needed for a diagnosis but if performed reveals cysts less than 2 cm; these cysts are often bilateral.

Abscess and Mastitis

Mastitis may occur in adolescents and may be caused by duct obstruction, an immune-compromised state, or nipple injury. Presentation may be with a painful lump with or without fever. The most common pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus. Sonographic appearance is that of a typical abscess characterized by a complex cystic mass with peripheral increased vascularity [1, 2].

Hematomas

Hematomas commonly result from sports or iatrogenic trauma and result in lumps that are sonographically complex and whose appearance will depend on the stage of hemorrhage; in the acute phase, these lesions are hyperechoic and progressively become cystic as the hematoma evolves. Mammograms are seldom performed and, when done, demonstrate a hyperattenuating mass in the acute phase with ill-defined margins; in the chronic phase, reactive changes around the hematoma may cause spiculation [1].

Neoplastic

Benign Breast Masses

Fibroadenoma, Juvenile Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenoma is a benign fibroepithelial neoplasm and the most common cause of a solid mass in girls younger than 20 years, accounting for well over 50 % of all such masses, 10/17 in one series and 91 % in another [4]. Fibroadenoma represents 91 % of all solid breast masses in girls younger than 19 years [5]. Presentation usually is a slowly enlarging mass that is mobile and nontender on clinical examination. A fibroadenoma can undergo faster growth in pregnancy. These benign tumors appear sonographically as circumscribed oval-shaped masses with uniform echogenicity measuring 2–5 cm (Fig. 11.1). About 7–10 % of these belong to a special type referred to as a juvenile or cellular fibroadenoma that tends to grow rapidly and attain a size of 5–10 cm when it is also referred to as a giant fibroadenoma [1, 6]. When seen, slender cystic spaces and clefts are characteristic of juvenile fibroadenoma. Juvenile fibroadenomas can have a macrolobulated appearance (Fig. 11.2). They are more commonly seen in African American girls and may be multiple and bilateral. Fibroadenomas are generally avascular although there may be occasional central vascularity. Histologically, juvenile fibroadenoma is characterized by cellular proliferation of stroma consisting of spindle cells in a myxoid stroma [1]. At imaging distinction between juvenile fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumor is difficult; peripheral cysts are more suggestive of the latter. Rapidly enlarging breast masses are generally excised due to difficulty in differentiating the two entities. Histological distinction between cellular fibroadenomas and benign phyllodes tumor can be challenging. For masses that are smaller and not rapidly growing, sonographic and clinical surveillance is all that is needed. About 10 % of the fibroadenomas in young girls can spontaneously regress [7]. Unnecessary intervention should be avoided so as not to damage the developing breast that can lead to aplasia or hypoplasia [8].

Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia (PASH)

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) is an entity that is generally seen in older women. It is histologically characterized by hormonally stimulated proliferations of myofibroblasts; rarely they may be seen in late adolescence and uncommonly grow rapidly. Clinically and on imaging, these lesions can have features similar to fibroadenomas. The mean size of these tumors is 4.2 cm with a range between 1 and 11 cm [9]. The name is derived from the characteristic histological feature of anastomosing slit-like channels lined by flat myofibroblastic cells that resemble endothelial cells and is surrounded by dense stroma [1]. When red blood cells are seen within these slit-like spaces on a core biopsy, it can be confused with an angiosarcoma [10]. On sonography, these masses appear as an oval circumscribed mass with margins that may be less well defined than a typical fibroadenoma; there may be a posterior acoustic enhancement associated with this mass. Conservative management after a diagnosis of PASH is recommended with excision reserved for symptomatic or enlarging masses.

Juvenile Papillomatosis

Juvenile papillomatosis is a localized benign proliferative disorder that is uncommonly seen in teens with a mean age of diagnosis at 19 years [11]. Histologically, there are multiple cysts and dilated ducts in a dense stroma, an appearance that has been characterized as “Swiss cheese disease.” Mammography may show an area of focal asymmetry or microcalcifications [12]. At sonography, an ill-defined mass with multiple cystic areas of varying sizes is seen at the periphery of the lesion [12]. Juvenile papillomatosis is a marker for familial breast cancer. About 5–15 % of patients have concurrent breast cancer and 33–58 % of cases have a positive family history of breast cancer [13, 14].

Intraductal Papilloma

Intraductal papillomas are rare in children and when seen appear as solitary circumscribed masses in a dilated duct and may be outlined by secretions within a duct. These tend to occur in the larger subareolar ducts. In 25 % of cases, papillomas may be bilateral [2]. Nipple discharge may be a presenting symptom. Histologically, these papillomas resemble juvenile papillomatosis.

Granular Cell Tumor

Granular cell tumor is a rare benign tumor; about 5–6 % of these occur in the breast and most commonly in premenopausal African American women [15]. These account for 1 % of breast tumors in children and originate from perineural cells. Granular cell tumors appear as 1–2 cm superficially located firm masses and may be associated with skin fixation or retraction. At mammography, they may appear as a spiculated mass or as a circumscribed mass. On ultrasound, the spiculated mass may demonstrate posterior acoustic shadowing and appear malignant. These are treated with wide excision when a histological diagnosis is achieved with percutaneous biopsy.

Malignant Tumors

Phyllodes Tumor

Phyllodes tumor is the most common primary breast malignancy in the adolescents. It is a stromal tumor arising from the lobular connective tissue [7]. A higher incidence has been reported in those with an Asian heritage. These tumors present as rapidly enlarging breast lumps. The benign types of phyllodes are more common in this age group. Phyllodes tumors occur predominantly in older women; however, about 5 % of these tumors are seen in girls younger than 20 years. Clinically, pathologically, and at imaging, these tumors may resemble a juvenile type of fibroadenoma [1]. Most tumors are larger than 6 cm with an average range of 8–10 cm [2]. A size less than 4 cm has a favorable prognosis as does presence of pushing rather than infiltrative borders, lack of necrosis, and lesser than three mitosis per high power field [1].

At sonography, these masses are circumscribed but tend to have a heterogeneous internal echotexture with clefts and cystic spaces compared to the more homogenous areas within a fibroadenoma (Fig. 11.3a, b). Mammography demonstrates a hyperdense circumscribed mass without calcifications; malignant types may exhibit pleomorphic microcalcifications. Recurrence is a feature noticed in both benign and malignant types; the former recurs about 10–25 % of the time and the recurrence rate in malignant phyllodes is greater than 40 % even following a wide excision [4]. About 5–24 % of phyllodes in those less than 20 years of age are malignant. Metastasis is uncommon but when present is hematogenous and to the lungs. Malignant types are histologically associated with sarcomatous elements, infiltrative margins, necrosis, cellular atypia, and increased stromal cellularity.

Carcinoma

Breast carcinoma in girls under the age of 20 years is exceedingly rare, and based on the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data from 2006 to 2010, 0.0 % was diagnosed [16]. Less than 1 % of breast lesions in children is caused by breast cancer [17]. The most common type is the secretory carcinoma that presents as a circumscribed mass less than 3 cm and with a pseudo capsule [1, 11]. Prognosis is favorable. Breast cancer in these girls may be related to inherited BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations [11]. Sonographic appearance is that of a malignant mass with irregular margins, taller than wide and with posterior acoustic shadowing.

Metastasis

The most prevalent malignant tumors in the breast in children and adolescents are metastasis. The most common tumors metastasizing to the breast are rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, and hematolymphoid malignancies [1, 18]. Breast metastasis has been reported in 6 % of patients with rhabdomyosarcoma [18]. Metastasis are frequently bilateral and multiple although a solitary mass may also be seen. Clinically, masses may exhibit rapid growth and be painful. Sonographic appearance is variable and may exhibit a spectrum of appearance leading to an indeterminate morphology prompting a tissue diagnosis.

Pregnancy and Lactation: Benign Abnormalities of the Breast

The physiologic changes occurring in pregnancy are induced by high circulating levels of estrogen and progesterone, and these lead to increase in breast size, its firmness, and increased nodularity. These changes continue for 3 months after cessation of lactation. Physical examination is difficult as a result of these changes in the breast and it is advised that a baseline clinical breast exam is performed during the first visit to the obstetrician [19]. Mammographic increase in density of the breast also limits its value during pregnancy and lactation. Pumping of the breast prior to a mammogram is also helpful. Ultrasound demonstrates diffuse increase in the echogenicity of normal breast tissue during pregnancy and lactation. During lactation, one sees distended ducts as hypoechoic tubular structures. Increased vascularity is also an expected feature [20].

The most common symptoms prompting imaging in pregnancy and lactation are a palpable lump, mastitis, and a bloody nipple discharge. Ultrasound is the initial imaging modality of choice and often the only modality that is utilized. Mammography is generally not performed in pregnancy although the radiation risk to the developing fetus is insignificant [21]. MRI of the breast is not an option during pregnancy since the safety of intravenous gadolinium has not been established in pregnancy. During lactation, MRI may be used if needed with instructions to stop breastfeeding for 24 h after [21].

Spontaneous Nipple Discharge in Pregnancy

Nipple discharge in pregnancy is uncommon; cytological examination of spontaneous nipple discharge is performed. If no pathology is seen and physical and ultrasound examination is normal, clinical follow-up is advised. If pathologic results are seen on cytology, galactography may be indicated to exclude an intraductal lesion such as a papilloma. Nipple discharge is an uncommon manifestation of pregnancy-associated breast cancer [21].

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenomas being hormone-sensitive tumors may manifest varied appearances in pregnancy and lactation due to superimposition of hormone-induced and or lactational changes. Previously unsuspected fibroadenomas may be discovered in pregnancy due to enlargement and becoming palpable or symptomatic. Palpable fibroadenomas generally require tissue diagnosis that is best achieved with percutaneous core biopsy. Nonpalpable solid masses without suspicious morphology may be followed. The appearance of a fibroadenoma on ultrasound in pregnancy and lactation is varied and the following descriptions have been used [21]. Gravid fibroadenomas may demonstrate large cysts, dilated ducts, or increased vascularity (Fig. 11.4). Fibroadenoma with infarction may present as a painful tender mass. Intravascular thrombi have been identified on occasion in these fibroadenomas; this occurs usually in the third trimester. A more lobulated contour, heterogeneous architecture and posterior acoustic shadowing may be seen in such tumors as a result of infarction. Fibroadenoma with lactational changes and secretory hyperplasia demonstrates dilated ducts within, hyperechogenicity, and cystic changes. Aspiration may sometimes reveal milk as in a galactocele; distinction from a lactating adenoma may be difficult as well although this is not a management issue. Lactational adenoma histologically lacks the myoepithelial proliferation that is characteristic of fibroadenoma.

Galactocele

Galactoceles are the most common benign breast lesions in lactating women but are more frequently seen after cessation of lactation due to stagnation and retention of milk in the breast [21]. These are cysts that are lined with flat or cuboidal epithelium containing fluid that resembles milk that contains a variable amount of protein, fat, and lactose. The underlying etiopathogenesis is ductal dilatation, surrounding fibrous wall, and varying degrees of inflammation. Aspiration is diagnostic and therapeutic. The imaging appearance is variable depending on the contents:

-

Pseudolipoma is when the entire content is fat in which case mammographically a lucent circumscribed mass is encountered that sonographically appears uniformly hyperechoic or hypoechoic (Figs. 11.5a–c and 11.6a–c). Cystic mass with fat fluid level is when there is a mixture of fat that rises on top of water contents leading to a fat fluid level seen on mediolateral mammograms and on ultrasound. This sign is characteristic of a galactocele but may occasionally be seen in fat necrosis (Fig. 11.7a–f).

Fig. 11.5 (a–c) A 31-year-old lactating woman with a palpable lump histologically proven to be a galactocele. (a) Ultrasound demonstrated a hyperechoic circumscribed solid mass. (b) Spot compression view in the mediolateral projection shows a mixed fat and soft tissue mass. (c) Spot compression view in the craniocaudal projection shows a mixed fat and soft tissue mass

Fig. 11.6 (a–c) A 31-year-old with a palpable lump in the right axilla adjacent to an accessory nipple consistent with a galactocele. (a) Ultrasound demonstrates a circumscribed solid hypoechoic mass with a shape simulating an enlarged abnormal axillary lymph node. (b) Ultrasound demonstrates a circumscribed solid hypoechoic mass with a shape simulating an enlarged abnormal axillary lymph node. (c) Spot compression mammographic view shows the ultrasound solid-appearing mass to be radiolucent mass consistent with a benign finding. The round density contiguous with this lesion corresponded to the accessory nipple

Fig. 11.7 (a–f) A 28-year-old lactating woman with a painful palpable lump histologically proven to be a galactocele. (a) Ultrasound demonstrated a complex cystic mass with echogenic contents and a mural nodule showing posterior acoustic shadowing. (b) US-guided aspiration with needle in the cystic mass and within the mural nodule. (c) Post core-needle biopsy, the cavity is partially collapsed. (d) Core specimen from the mural nodule and cyst wall. (e) Milky aspirate from the galactocele in a syringe. (f) Post-biopsy mediolateral oblique view demonstrates a fat density mass with the post-biopsy clip and a fat fluid level

-

Pseudohamartoma is an appearance more often seen in chronic galactocele where a mixed fat and soft tissue density mass is seen resembling a hamartoma. Galactoceles can get infected and painful; aspiration in such cases may reveal purulent material with positive culture.

Galactocele can have a complex cystic mass with thick internal septations. Aspiration causes the lesion to partially collapse and reveals milk-like aspirate (Figs. 11.7a–f and 11.8a, b).

Lactating Adenoma

Lactating adenomas are benign tumors of the breast typically seen in the third trimester and during lactation [20]. These masses resemble fibroadenoma clinically and on imaging appear as circumscribed mobile oval-shaped masses. When infracted, they appear as firm tender masses [22]. Histologically unlike a fibroadenoma, these have very little stromal elements and consist predominantly of epithelial elements. These elements consist of mature tubules containing actively secreting cells filling up the acini with secretions [22]. Lactating adenomas uniquely tend to regress after cessation of breastfeeding [23]. At sonography, posterior acoustic enhancement and increased lesion compressibility is characteristic likely due to large amount of secretions in the acini (Figs. 11.9a, b, 11.10a–c, and 11.11a–c) [22]. Infarction leads to appearance of irregular margins and posterior acoustic shadowing.

(a, b) A 34-year-old woman with a palpable lump during lactation revealed a lactating adenoma. (a) Ultrasound demonstrates a solid mass with multiple tubular cystic structures within representing dilated ducts. (b) Follow-up ultrasound at 12 months reveals the mass being smaller and without the lactational changes of dilated ducts

(a–c) A 34-year-old with a palpable lump histologically proven to be an infracted lactating adenoma. (a) Ultrasound demonstrated a solid indeterminate mass. (b) Mediolateral oblique mammogram shows a round dense mass with obscured borders. (c) Craniocaudal mammogram shows a round dense mass with obscured borders

(a, b) A 36-year-old with a palpable lump in the left breast with histologically proven infracted lactating adenoma. Ultrasound demonstrates a superficially located solid mass with heterogeneous echotexture and circumscribed lobulated borders. Appearance was consistent with an indeterminate mass with a recommendation for ultrasound-guided core biopsy

Juvenile Papillomatosis

There is an increased frequency of benign proliferative disease during pregnancy and lactation [21]. Juvenile papillomatosis is generally seen in young women. An association with pregnancy has been proposed based on finding 5 cases of this entity in a series of 18 pregnant patients [21]. On ultrasound, juvenile papillomatosis appears as an ill-defined mass that is composed of multiple cysts surrounded by fibrous septa and well demarcated histologically from surrounding tissue. The cystic and ductal hyperplasia is associated with papillary hyperplasia lining the cystic spaces [24]. Definitive treatment is by surgical excision with negative margins required to avoid local recurrence [21]. In young women, juvenile papillomatosis is a risk factor for breast cancer with a reported association with breast cancer in 15 % of cases and a reported incidence of breast cancers in up to 50 % of female relatives [21, 24].

Granular Cell Tumor

This is a rare benign tumor seen in young women. About 5–6 % are seen in the breast and more commonly seen in African American women. They arise from perineural cells. Clinically, these present as superficial firm masses and there may be associated skin changes [1]. Histologically, they tend to form an infiltrative growth and simulate an infiltrative carcinoma, clinically and on imaging. At sonography, these appear as 1–2 cm irregular masses with posterior acoustic shadowing and tend to exhibit characteristics of a malignant mass (Fig. 11.12a, b). At mammography, these may appear as spiculated masses and simulate invasive ductal cancers; these can also appear as well-circumscribed masses. Despite the malignant appearance on imaging, these tumors are benign and preoperative diagnosis is important to treat appropriately with wide excision [1].

Granulomatous Mastitis

Granulomatous mastitis is a rare chronic inflammatory condition of the breast of unknown etiology. It affects women of childbearing age who most commonly present with an inflamed breast mass with or without pain. This condition is benign but needs to be differentiated from inflammatory breast cancer and other chronic inflammatory conditions of the breast. There has been reported association with tuberculosis and HIV infection [25]. In one of the largest reported series of 41 cases seen over a period of 10 years, affliction was predominantly unilateral (95 %); a mass was found in 78 % on clinical examination and in 52 % on mammography and ultrasound. Tenderness (41 %) and erythema were less common (29 %); the subareolar region is typically spared. At ultrasound, multiple clustered tubular hypoechoic structures or poorly defined large hypoechoic masses may be seen and often mistaken for malignancy. Mammography may not demonstrate an abnormal finding especially in a dense breast or may show a mass or a focal asymmetry [21]. Reactive lymphadenopathy has been seen in 15 % of cases. Histologically at core biopsy, abundance of epithelioid histiocytes among a predominantly neutrophilic background is characteristic. Noncaseating granuloma formation within the breast parenchyma centered on breast lobules is typically seen. Prognosis is good; steroid therapy and excisional biopsy have been shown to be effective [21].

Fat Necrosis and Inflammation

Minor trauma to the breast may result in fat necrosis and inflammation. Presentation is with a painful lump. Ultrasound may show a solid hyperechoic mass; mammogram may reveal a partly radiolucent mass or an iso- or high-density mass interspersed with fat (Fig. 11.13a–c).

(a–c) A 27-year-old woman during lactation with a painful palpable lump in the right breast histologically proven to be fat necrosis with inflammatory changes. (a) Ultrasound demonstrates an ovoid hyperechoic mass. (b) Spot magnification view in the mediolateral oblique view demonstrates a mixed density mass. (c) Spot magnification view in the craniocaudal view demonstrates a mixed density mass

Mastitis and Breast Abscess

Infection of the breast predominantly affects young women and occurs most commonly during lactational period. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative organism followed by streptococcus. Staphylococcus infection tends to be invasive and localized with a greater propensity for abscess formation, whereas streptococcus infection presents as diffuse mastitis with abscess formation seen only in late phases [26]. There are several types of clinical presentation, and these are discussed next.

Puerperal Mastitis

Mastitis is said to occur in 1–24 % of breastfeeding women [27]. Breast abscess is reported to complicate puerperal mastitis in 5–11 % of cases [28]. The organism gains entry through cracked nipples during lactation originating from the nasopharynx or mouth of the infant and proliferates in the stagnant lactiferous ducts. Breastfeeding is encouraged during mastitis to drain such engorged ducts. Breastfeeding cessation is only advised following surgical drainage or if the mother is on an antibiotic that is contraindicated for the newborn [26].

Central Nonpuerperal Abscess

In women who are not lactating, the most common type of abscess is the central nonpuerperal type. These occur predominantly in young women who are smokers. Cessation of smoking should be strongly advised, and in those over 35 years of age, mammography is indicated to exclude malignancy. Cigarette smoke induced changes in the epithelium of the retroareolar ducts leading to formation of keratin plugs, periductal mastitis, distension and obstruction of the ducts, and stagnation, and infection ensues [26]. Treatment is by means of percutaneous drainage. Bilaterality is common and reported in 25 % of cases and recurrence also occurs in 25–40 % of cases.

Peripheral Nonpuerperal Abscess

These are less common and seen in older women. These may be seen in women with chronic underlying conditions such as diabetes mellitus or rheumatoid arthritis. Steroid therapy or recent breast interventions are also potential underlying factors [26]. In most women with nonpuerperal peripheral mastitis, there is no underlying condition. Treatment is by drainage and antibiotics and recurrence is rare.

Imaging in Mastitis and Breast Abscess

Pain, redness, heat, and palpable lumps are frequently seen in those with mastitis and abscess; fever is uncommon. In a series of breast abscesses with lumps, 80 % were painful and 71 % were associated with redness of the overlying skin with only 12 % associated with fever [29]. Abscess is seen in 40–65 % of cases on ultrasound and at more than one site in 21 % of cases [27].

At ultrasound which is the initial and often the only imaging modality that is used for diagnosis and management, mastitis appears as ill-defined areas of increased echogenicity in the fat lobules and as areas of decreased echogenicity in the glandular parenchyma. Skin thickening is frequently observed. Reactive lymphadenopathy is seen as lymph nodes that are enlarged with diffuse thickening of the cortex and preservation of the fatty hilum and increased vascularity. Abscess is seen as an irregular fluid collection with multiloculation, posterior acoustic enhancement, and sometimes with a hyperechoic rim showing increased vascularity (Fig. 11.14a, b). Mammography is performed in older women, in those not responding to treatment, or for those who are not lactating mainly to exclude malignancy. Mammography is deferred until the acute phase has subsided to avoid the added discomfort of compression. Skin thickening, focal asymmetry or a mass are signs that may be present but are nonspecific and do not help in the distinction from malignancy. Presence of suspicious microcalcifications, however, is worrisome and should prompt biopsy. In a series of 975 cases of suspected mastitis, there were 6 cases of inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) [26]. In two of these cases, there were suspicious microcalcifications seen at mammography. Mastitis that is seen in a nonpuerperal setting or one that is not responding to treatment should raise the suspicion of IBC particularly in older women. Pain in IBC is generally less severe than in mastitis; skin thickening is also more localized than in IBC. Suspicious microcalcifications are seen in up to 47 % of cases of IBC and hence when seen is the most specific sign of an underlying malignancy [26]. The finding of a mass on mammography and more frequently on an ultrasound is also more indicative of an underlying malignancy. There can still be some overlap in the imaging findings between mastitis and abscess and IBC posing diagnostic challenges [30].

Pregnancy-Associated Breast Cancer

Breast cancer that is diagnosed during pregnancy or within 1 year after childbirth is included in the definition of pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) [31]. PABC has been traditionally associated with poor prognosis and an advanced stage at presentation mainly due to delay in diagnosis [32, 33]. In an analysis of 104 PABC among 652 women under the age of 35 years with breast cancer, there was found to be no statistically significant difference in locoregional recurrence, distant metastasis, or in overall survival among women with PABC compared to those in nonpregnant women. It was, however, noted in this retrospective study that pregnancy caused a delay in diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment [34]. The authors found that any treatment intervention during pregnancy resulted in improved survival when compared to those whose treatment was delayed due to pregnancy. Primary care physicians and obstetricians should aggressively pursue workup of breast symptoms in pregnancy for a prompt diagnosis of breast cancer and appropriate initiation of multidisciplinary treatment. The spectrum of the imaging appearance of PABC has been well described in literature [31, 35–37]. PABC is rare and has been reported in 0.3 per 1000 pregnancies [38]. About 2/3 of these cancers are diagnosed in the postpartum period [35].

Imaging Evaluation in PABC

Under the influence of hormones estrogen, progesterone, and prolactin, there is proliferation of ducts and lobules, increased secretion, and enlargement of the lobular acini with colostrums. These changes in the breast parenchyma lead to a marked increase in the breast density and make it nodular with decreased fat tissue [36]. Clinical evaluation is limited for these reasons. This also causes significantly decreased sensitivity of mammography. A persistent localized palpable finding needs to be further evaluated by imaging. Sonography is the imaging modality of choice. Abnormal mammographic findings when seen in PABC include masses, asymmetric density, suspicious calcifications, skin and trabecular thickening, and axillary adenopathy. Widespread calcifications have been reported in 26 % of cases of PABC [37]. Sonography is the initial imaging modality for the evaluation of breast symptoms in pregnancy with a reported sensitivity of 100 % for the diagnosis of breast cancer [36]. The negative predictive value of sonography is 100 % [36]. Sonography is useful in distinguishing benign changes from a solid tumor and can predict malignancy accurately using morphologic criteria described by Stavros (Fig. 11.15a, b) [39]. However, there are certain features that are more commonly associated with benign masses that may be more commonly associated with PABC. Parallel orientation is one such feature that was found in 58 % of cancers in one series [36]. Due to rapid growth and increased vascularity, cystic changes may also be encountered in PABC; hence, complex cystic masses in pregnancy need a tissue diagnosis so as not to mistake PABC for a galactocele or an abscess. Similarly, posterior acoustic enhancement is a more commonly encountered feature of a mass in PABC compared to those in a nonpregnant patient [36]. Mammography reveals positive findings in 74–87 % despite sensitivity being reduced due to increased breast density [36, 37]. A negative sonographic study should prompt biopsy when the mass is clinically suspicious. Mammography is generally performed when initial evaluation is suspicious for malignancy. Invasive ductal cancers constitute a large percentage of PABC accounting for 58–91 % of cases [36, 37]. Ultrasound of the axilla is useful in identifying metastatic nodes in patients with PABC. Some authors have found ultrasound of the axilla more useful [40] than others [37]. Inflammatory breast cancer is not more prevalent in pregnancy; about 2–18 % of breast cancers in pregnancy are inflammatory breast cancer [36, 41]. However, since mastitis is more prevalent during lactation, having a high index of suspicion for IBC is important particularly in cases not responding to treatment (Fig. 11.16a, b).

(a, b) A 28-year-old woman with a palpable lump in her right breast initially misinterpreted as a cyst (images not shown). Mass continued to enlarge. Subsequent biopsy revealed an infiltrating carcinoma. (a) Ultrasound shows a large solid mass with lobulations and ill-defined borders. (b) Doppler imaging demonstrates peripheral and internal vascularity

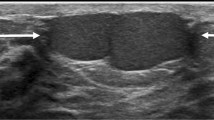

(a, b) A 29-year-old woman with a progressively enlarging mass and skin changes during pregnancy histologically proven inflammatory breast cancer. (a, b) Ultrasound of the affected breast performed following childbirth demonstrates a very large irregular hypoechoic mass (arrows). There is marked thickening of the skin (arrowheads)

Breast Cancer in the Young Woman

There has been a steady improvement in the outcomes of treatment for breast cancer with 5-year disease-free survival being 75–85 %. Most of the improvement in the outcome is attributed to early detection due to the widespread use of screening mammography. More than half of all patients that are screened with mammography have stage 0 or stage I disease [42, 43]. Conversely, 71 % of breast cancer deaths were reported to be in women who had not undergone screening mammography compared to 29 % in women who had undergone regular screening mammography [44]. The benefit of screening does not apply to women under the age of 40 years in whom screening for breast cancer is not recommended for those at average risk for breast cancer. A low prevalence of breast cancer combined with reduced sensitivity of mammography makes this modality not a cost-effective intervention in young women. There has been no improvement in breast cancer survival over the years in women under the age of 40 years.

Breast cancer occurs less frequently in women under the age of 40 years. The prevalence of cancer in this group of women who are not routinely screened when at average risk is low. Interestingly, the risk of developing cancer in women under 40 years of age is similar throughout the world including the developing nations that have seen a dramatic increased incidence of breast cancer in recent years [45]. The worldwide average for developing breast cancer before 40 years of age is 0.3 % and is similar in Japan, Canada, Bangladesh, and Nigeria [45, 46]. The cumulative risk of breast cancer to age 39 in the USA is 0.45 and in Canada 0.38 [45]. The low prevalence of disease means that screening is not a feasible or cost-effective tool to detect cancers at an early stage. Risk factors in young women include a lean body habitus and recent use of contraceptives [46]. In the USA, based on estimates of the American Cancer Society, there will be 230,000 women who will receive a diagnosis of invasive breast cancer, only 5 % of which will be in women under 40 years of age [47]. Breast cancer in young women tends to be aggressive, of higher grade with a greater proportion of triple-negative tumors. Additionally, young age is an independent negative predictor of cancer-specific survival. Local recurrence and contralateral disease are higher. Increasing breast cancer awareness may lead to diagnosing cancers when smaller than 2.0 cm with consequent improved mortality. A study compared the risk factors, clinical presentation, pathologic findings, tumor characteristics, extent of disease, treatment, and outcomes for 101 women under the age of 36 treated for breast cancer with 631 patients 36 years or older. Patients under the age of 36 years diagnosed with breast cancer presented more often with a palpable mass; cancers were more aggressive and advanced (Figs. 11.17a–e and 11.18a–d). Despite aggressive treatment with chemotherapy and mastectomy, local and distant metastases were higher; local and distant failure rates were also higher. A majority of patients younger than 36 years were diagnosed with stage II or stage III disease, whereas majority of cancers in women greater than 36 years of age were diagnosed with stage 0 or stage I disease [48].

(a–e) A 31-year-old woman with a palpable lump in the left breast histologically proven to be DCIS with invasive component. (a) Left mediolateral oblique view demonstrates extensive pleomorphic calcifications in the area of palpable abnormality. (b) Left craniocaudal projection view demonstrates extensive pleomorphic calcifications in the area of palpable abnormality. (c) Magnification view in the mediolateral projection demonstrates pleomorphic calcifications in a segmental distribution highly suggestive of malignancy. (d) Magnification view in the craniocaudal projection demonstrates pleomorphic calcifications in a segmental distribution highly suggestive of malignancy. (e) Ultrasound demonstrates a solid mass with intraductal calcifications

(a–d) A 24-year-old woman with a family history of cancer and a palpable lump in the right breast histologically proven to be invasive ductal cancer. (a) Right mediolateral oblique view demonstrates pleomorphic microcalcifications highly suggestive of cancer. (b) Magnification view shows linearly distributed pleomorphic calcifications in greater detail. (c) Ultrasound demonstrates a poorly defined hypoechoic area with intraductal microcalcifications (arrows). (d) Ultrasound of the right axilla demonstrates a markedly enlarged lymph node with replacement of the fatty hilum proven at fine-needle aspiration biopsy to be a metastatic lymphadenopathy

Due to the fact that mammographic screening is not routinely offered or recommended in women under the age of 40 years, breast cancer awareness is of importance to detect cancer at an earlier stage. The size of the cancer being the predictor of long-term survival, increasing awareness may potentially lead to young women seeking earlier attention for breast symptoms.

References

Chung EM, Cube R, Hall GJ, González C, Stocker JT, Glassman LM. From the archives of the AFIP: breast masses in children and adolescents: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29(3):907–31.

Greydanus DE, Matytsina L, Gains M. Breast disorders in children and adolescents. Prim Care. 2006;33:455–502.

Welch ST, Babcock DS, Ballard ET. Sonography of pediatric male breast masses: gynecomastia and beyond. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:952–7.

Vade A, Lafita VS, Ward KA, Lim-Dunham JE, Bova D. Role of breast sonography in imaging of adolescents with palpable solid breast masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(3):659–63.

Sanchez R, Ladino-Torres MF, Bernat JA, Joe A, DiPietro MA. Breast fibroadenomas in the pediatric population: common and uncommon sonographic findings. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1681–9.

Sklair-Levy M, Sella T, Alweiss T, Craciun I, Libson E, Mally B. Incidence and management of complex fibroadenomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:214–8.

West KW, Rescoria FJ, Scherer III LR, Grosfeld JL. Diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic breast masses in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:182–6; discussion, 186–7.

García CJ, Espinoza A, Dinamarca V, et al. Breast US in children and adolescents. Radiographics. 2000;20:1605–12.

Ferreira M, Albarracin CT, Resetkova E. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia tumor: a clinical, radiologic and pathologic study of 26 cases. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:201–7.

Kaneda HJ, Mack J, Kasales CJ, Schetter S. Pediatric and adolescent breast masses: a review of pathophysiology, imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(2):W204–12.

Coffin CM. The breast. In: Stocker JT, Dehner LP, editors. Pediatric pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. p. 993–1015.

Sabate JM, Clotet M, Torrubia S, et al. Radiologic evaluation of breast disorders related to pregnancy and lactation. Radiographics. 2007;27(Spec Issue):S101–24.

Bazzocchi F, Santini D, Martinelli G, et al. Juvenile papillomatosis (epitheliosis) of the breast: a clinical and pathologic study of 13 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1986;86:745–8.

Rosen PP, Kimmel M. Juvenile papillomatosis of the breast: a follow-up study of 41 patients having biopsies before 1979. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93:599–603.

Adeniran A, Al-Ahmadie H, Mahoney MC, Robinson-Smith TM. Granular cell tumor of the breast: a series of 17 cases and review of the literature. Breast J. 2004;10:528–31.

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2010. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2013.

Gains M. Breast disorders in children and adolescents. Prim Care. 2006;33:455–502.

Howarth CB, Caces JN, Pratt CB. Breast metastases in children with rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer. 1980;46:2520–4.

Gemignani ML, Petrek JA. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer: diagnosis and treatment. Breast J. 2000;6:68–73.

Vashi R, Hooley R, Butler R, Geisel J, Philpotts L. Breast imaging of the pregnant and lactating patient: physiologic changes and common benign entities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(2):329–36.

Sabate JM, Clotet M, Torrubia S, Gomez A, Guerrero R, de las Heras P, Lerma E. Radiologic evaluation of breast disorders related to pregnancy and lactation. Radiographics. 2007;27 Suppl 1:S101–24.

Stavros AT. Breast ultrasound. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.

Sumkin JH, Perrone AM, Harris KM, Nath ME, Amortegui AJ, Weinstein BJ. Lactating adenoma: US features and literature review. Radiology. 1998;206:271–4.

Rosen PP. Breast tumors in children. In: Rosen PP, editor. Rosen’s breast pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2001. p. 729–48.

Mohammed S, Statz A, Lacross JS, Lassinger BK, Contreras A, Gutierrez C, Bonefas E, Liscum KR, Silberfein EJ. Granulomatous mastitis: a 10 year experience from a large inner city county hospital. J Surg Res. 2013;184(1):299–303.

Trop I, Dugas A, David J, El Khoury M, Boileau JF, Larouche N, Lalonde L. Breast abscesses: evidence-based algorithms for diagnosis, management, and follow-up. Radiographics. 2011;31(6):1683–99.

Ulitzsch D, Nyman MK, Carlson RA. Breast abscess in lactating women: US-guided treatment. Radiology. 2004;232(3):904–9.

Thomsen AC, Espersen T, Maigaard S. Course and treatment of milk stasis, noninfectious inflammation of the breast, and infectious mastitis in nursing women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149(5):492–5.

Leborgne F, Leborgne F. Treatment of breast abscesses with sonographically guided aspiration, irrigation, and instillation of antibiotics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(4):1089–91.

Renz DM, Baltzer PAT, Böttcher J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of inflammatory breast carcinoma and acute mastitis: a comparative study. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(11):2370–80.

Vashi R, Hooley R, Butler R, Geisel J, Philpotts L. Breast imaging of the pregnant and lactating patient: imaging modalities and pregnancy-associated breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200(2):321–8.

Treves N, Holleb AI. A report of 549 cases of breast cancer in women 35 years of age or younger. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1958;107:271–83.

Woo JC, Yu T, Hurd TC. Breast cancer in pregnancy: a literature review. Arch Surg. 2003;138:91–8.

Beadle BM, et al. The impact of pregnancy on breast cancer outcomes in women < or = 35 years. Cancer. 2009;115(6):1174–84.

Ayyappan AP, Kulkarni S, Crystal P. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer: spectrum of imaging appearances. Br J Radiol. 2010;83(990):529–34.

Ahn BY, Kim HH, Moon WK, Pisano ED, Kim HS, Cha ES, Kim JS, Oh KK, Park SH. Pregnancy- and lactation-associated breast cancer : mammographic and sonographic findings. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22(5):491–7.

Taylor D, Lazberger J, Ives A, Wylie E, Saunders C. Reducing delay in the diagnosis of pregnancy-associated breast cancer: how imaging can help us. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2011;55(1):33–42.

Keleher AJ, Theriault RL, Gwyn KM, Hunt KK, Stelling CB, Singletary SE, et al. Multidisciplinary management of breast cancer concurrent with pregnancy. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:54–64.

Stavros AT, Thickman D, Rapp CL, Dennis MA, Parker SH, Sisney GA. Solid breast nodules: use of sonography to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. Radiology. 1995;196:123–34.

Yang WT, Dryden MJ, Gwyn K, Whitman GJ, Theriault R. Imaging of breast cancer diagnosed and treated with chemotherapy during pregnancy. Radiology. 2006;239:52–60.

Petrek JA. Breast cancer during pregnancy. Cancer. 1994;74:518–27.

Osteen RT, Cady B, Chmiel JS, et al. 1991 national survey of carcinoma of the breast by the Commission on Cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:213–9.

Tartter PI. Prognosis. In: Hermann G, Schwartz IS, Tartter PI, editors. Nonpalpable breast cancer: diagnosis and management. New York: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers; 1992. p. 112–9.

Webb ML, Cady B, Michaelson JS, Bush DM, Calvillo KZ, Kopans DB, Smith BL. A failure analysis of invasive breast cancer. Cancer. 2013. doi:10.1002/cncr.28199.

Ferlay J et al. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC cancer base no. 10. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer [online]; 2010. http://globocan.iarc.fr.

Narod SA. Breast cancer in young women. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(8):460–70.

Peres J. Advanced breast cancer in young women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(17):1257–8.

Gajdos C, Tartter PI, Bleiweiss IJ, Bodian C, Brower ST. Stage 0 to stage III breast cancer in young women. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190(5):523–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shetty, M.K. (2015). Imaging of the Symptomatic Breast in the Young, Pregnant, or Lactating Woman. In: Shetty, M. (eds) Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1267-4_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1267-4_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4939-1266-7

Online ISBN: 978-1-4939-1267-4

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)