Abstract

A substantial number of studies have shown that religiosity is associated with positive psychological outcomes across cultural contexts. Religious believers generally exhibit higher self-esteem and are generally better adjusted than nonbelievers (see Gebauer et al., Psychol Sci 23:158–160, 2012, for an overview). Such positive effects are generally evident when there is some value placed on religion. In many acculturation scenarios, the faith of the believer is not valued, and often experienced as culturally distant by the host society, as it is the case particularly for many Muslims of Turkish or Arab origin in Europe. Can there then be any positive effect of religiosity under such circumstances?

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

A substantial number of studies have shown that religiosity is associated with positive psychological outcomes across cultural contexts. Religious believers generally exhibit higher self-esteem (Aydin et al. 2010; Rivadeneyra et al. 2007) and are generally better adjusted (Koenig et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2003) than nonbelievers (see Gebauer et al. 2012 for an overview). Such positive effects are generally evident when there is some value placed on religion (Gebauer et al. 2012; Okulicz-Kozaryn 2010). In many acculturation scenarios, the faith of the believer is not valued, and often experienced as culturally distant by the host society, as it is the case particularly for many Muslims of Turkish or Arab origin in Europe (Van de Vijver 2009). Can there then be any positive effect of religiosity under such circumstances?

Literature on religiosity suggests that it has protective effects (Leondari and Gialamas 2009), but such effects have not received much attention from an acculturation perspective (Ward 2013; for an exception, see Friedman and Saroglou 2010). So far, studies have mainly demonstrated the importance of adopting the culture of the host society, and not maintaining one’s culture of origin for positive acculturation outcomes (Sam 2006). There is also evidence that religiosity is negatively related to the host culture adoption but positively associated with ethnic orientation (for an overview, see Saroglou 2012). A recent study even suggests that religiosity is indirectly related to depressive symptoms and lower self-esteem for stigmatized groups (see Friedman and Saroglou 2010).

We argue, however, that positive valuation may not come only from the relationship with the host society. Religiosity may act as a cultural group marker related to ethnic identification, and thereby provides a point of reference for the negotiation of a cultural sense of belonging (Dimitrova et al. 2012; Saroglou 2011; Verkuyten and Yildiz 2007). In other words, a strong religious orientation results in a psychologically adaptive adjustment to the ethnic community (Cadge and Ecklund 2007; Viladrich and Abraido-Lanza 2009). As it is likely that there are multiple roads to developing self-worth or preventing its decline (e.g., by identifying with one’s ethnic group; Verkuyten 2007), we expect that the interplay between religiosity and acculturation attitudes, particularly the maintenance of the immigrant’s culture of origin, is crucial for positive psychological outcomes.

In this chapter, we present how a sample of Turkish–Dutch second-generation immigrant adolescents negotiates religiosity, choices, and attitudes in the acculturative process and how this is associated with their acculturation outcomes (Arends-Tóth and Van De Vijver 2003). In particular, we expect that in a sample of second-generation Turkish–Dutch adolescent immigrants, religiosity and cultural maintenance interact with each other in their association with self-esteem . In the following, we first introduce the concepts of acculturation and religiosity, summarize research investigating their respective links with positive psychological outcomes, and provide an introduction to the Turkish–Dutch context.

Host Culture Adoption and Heritage Culture Maintenance—Implications for Acculturation Outcomes

Acculturation describes the process of an immigrant negotiating whether or not to explore the host cultural context while at the same time either maintaining or shedding one’s own cultural background (in adolescents often in the form of parental culture). These decisions can be prototypically summarized by Berry’s acculturation orientations: integration (maintaining the culture of origin while seeking contact to the host culture), assimilation (seeking contact to the host culture while shedding the culture of origin), separation (maintaining culture of origin while not seeking contact with host culture), and marginalization (neither maintaining culture of origin nor seeking contact with host culture; Berry 1997). Generally, acculturation research distinguishes between a public and a private domain in which this process may take place (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2004). It has been found that the host culture is more salient in the public domain, that is, the individual’s interaction with authorities or at work, while at the same time, the immigrant’s culture of origin is more prevalent in the private domain of life, which encompasses family activities, marital choices, or the upbringing of children (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2004; Van de Vijver and Phalet 2004). The salience of differences between the host society and family culture, and the willingness to maintain their own culture and feeling a part of the host society differ between immigrant groups (Phinney et al. 2001).

Generally, an acculturation orientation of integration (endorsement of both heritage and mainstream culture) is associated with positive developmental outcomes for adolescents , while marginalization (the dissociation from both cultures) is related to mental health problems among immigrants (Berry et al. 2006; Sam and Berry 2006, see also Boski 2008; Ward 2013 for different approaches to integration). Particularly, adoption of the host culture seems connected to positive acculturation outcomes (Ryder et al. 2000; Sam 2006). Moreover, an acculturation orientation of adoption has been found to act as a stepping stone toward more inclusive and complex identities (Saroglou and Mathijsen 2007).

Such positive effects, however, need to be differentiated. Empirical research has found that mainstream culture adoption indeed fosters sociocultural outcomes (e.g., competencies in the host culture; Ward 2001). At the same time, there is a clear positive relation between heritage culture maintenance and psychological well-being (Schwartz et al. 2009; Smith and Silva 2011). Beirens and Fontaine (2011) suggest that it may depend on the context of the immigrant which outcomes would be more critical. For those immigrants who worked in a predominantly host culture context, language proficiency, being knowledgeable about cultural norms and conventions, having host culture friends, and attending the host media would come with many benefits. If that is not the case, for instance, if the immigrant would be unemployed, working at home, or being otherwise separated from participation with the host society, maintenance of the heritage culture might be more important for psychological outcomes (Beirens and Fontaine 2011).

To better understand potential positive contributions of heritage culture maintenance, we suggest drawing on the rejection-identification model formulated by Branscombe et al. (1999). They proposed that social adversity may prompt individuals to strengthen ties with the rejected group. That way, heritage culture maintenance and ethnic identification may serve as buffers against discrimination, prejudice, and assimilation pressures (Phinney et al. 2001). In this vein, numerous researches have discussed heritage culture maintenance as a source for adaptive acculturation outcomes (Saroglou 2011; Verkuyten and Yildiz 2007; Verkuyten 2007; see also Sirin and Fine 2007). Particularly among Muslim immigrant groups in Europe , religious belief practices are critically important for the acculturative process because these are experienced as culturally distant from the host society (Saroglou et al. 2009b). We, therefore, propose to look at more closely at the role of religiosity in an acculturation setting.

Religiosity as a Protective Factor in an Acculturation Context

We are interested in the effects of religiosity on everyday life and decisions (Chattopadhyay 2007; Myers 1996). Religiosity can be considered an individual’s “reference to (what they consider to be a) transcendence through beliefs, rituals, moral norms, and/or community, somehow regulated by an institutionalized authority” (Saroglou 2012, p. 393 see also Houskamp et al. 2004). Being religious is linked to many positive psychological outcomes (Sedikides 2010) such as well-being and longevity (Strawbridge et al. 1997), marital stability, or low delinquency (Hood et al. 2009), happiness (Argyle 2001), it satisfies self-enhancement concerns (e.g., perceiving the self favorably; Sedikides and Gebauer 2010; Sedikides 2010), and it has been observed to have positive effects on adolescent development (see meta-analysis by Cheung and Yeung 2011; review by Saroglou 2012).

Since 9/11, religiosity, especially the practice of Islam, has received considerable attention in the popular discourse (Sedikides 2010; Sheridan 2006). At the same time, research on religiosity has also seen increased interest from cultural researchers, but our understanding of the interplay between religiosity and culture is still rudimentary (Lonner 2011; Matsumoto and Juang 2008). We know little about how religious attachment and adjustment to the acculturative process operate in Muslim immigrants in Europe , where private and public, that is, family and mainstream contexts, are culturally distant in their religious orientations (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2004; Voas and Crockett 2005).

Religion can be considered one of the cornerstones that gives meaning to life, informs sociocultural values, and it has been put forward that it may act as a protective factor, in particular, for immigrants. Saroglou and Mathijsen (2007) provided evidence that upholding one’s religious beliefs reinforces the attachment to one’s culture of origin. Verkuyten and Yildiz (2007) go one step further: they found that among those immigrants highly identifying with their religion the identification with the national identity is reduced, and an active distancing from the host culture takes place. This seems to suggest that heritage culture maintenance and religiosity act in concert and in a similar direction—both represent a focus on the heritage culture in daily living and everyday experiences. We, therefore, perceive religion as a strong form of culture (Cohen 2009; Lehman et al. 2004; see also Dimitrova et al. 2012).

It is therefore not surprising that a strong endorsement of religiosity is consistently accompanied by a strong ethnic identification, and even a disengagement from the host culture for immigrant Muslims (Saroglou and Mathijsen 2007; for an overview, see Saroglou 2012). In such a fashion, they might be a source for self-esteem and positive distinctiveness (Verkuyten 2005) and may represent a viable route to achieve positive psychological outcomes in an immigration scenario (Awad 2010) —which is in line with predictions from the rejection-identification model (Branscombe et al. 1999).

Religiosity strengthens social ties with fellow believers (Emmons and Paloutzian 2003), and is a valued part of the heritage culture for both first- and second-generation Muslims (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2004; Saroglou and Galand 2004). Furthermore, religiosity may contribute to pride and the development of a sense of responsibility (e.g., Juang and Syed 2008; King and Roeser 2009). An example for the positive effects can be found in the explicit choice of Muslim women to wear the hijab (a traditional veil that covers the head) in public—a practice that is disliked by and discriminated against by majority groups (Saroglou et al. 2009b). There is suggestive evidence from a small sample of Muslim-American women that wearing the hijab is a means of resisting sexual objectification, gaining respect, maintaining relationships as well as freedom—and it was related to greater well-being (Droogsma 2007). Such a protective effect is in line with general findings on religiosity (Leondari and Gialamas 2009), including findings on immigrants and refugees (Harker 2001; Whittaker et al. 2005), and resonates with the finding that a positive attitude toward one’s ethnic group enhances self-esteem (Phinney et al. 1997).

However, it also needs to be mentioned that Friedman and Saroglou (2010) found among Belgian Muslim late adolescents religiosity to be indirectly (via perceived religious intolerance exhibited by mainstreamers) related to decreased self-esteem and even increased depressive symptoms. If religion is stereotyped, the adaptive process becomes increasingly difficult (Foner and Alba 2008; see also Saroglou et al. 2009b) and results in negative self-evaluations. In other words, there are conditions under which stigmatization cannot be buffered against by ethnic or religious endorsement. Thus, the question seems warranted whether the generally positive effects of religiosity on well-being would also hold against the aforementioned considerations in an acculturation context. Confronted with adverse conditions (like in the acculturation context as Muslim immigrants), group identity is likely to be salient (Turner et al. 1987). It may seem probable that ethnic minority members thus seek psychological refuge in the belongingness to their group. Although such a process may result in negative feelings (e.g., anger; Van Zomeren et al. 2008), it may not always lower an individual’s sense of self-worth.

We, therefore, conclude that immigrant religiosity can contribute to acculturative adjustment , as a marker of group identity and belonging and as a source of self-esteem , social support , and cultural continuity across generations (Bankston 1997; Ebaugh and Chafetz 2000; Warner and Wittner 1998). It is now important to investigate under which conditions such beneficial effects can be reaped.

The Present Study: Turkish–Dutch Adolescents

Turkish immigrants in The Netherlands form the largest ethnic minority , and are characterized by a high ethnic vitality and predominantly maintain Turkish cultural traditions (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2009; Crul and Doomernik 2003). They generally are of a lower socioeconomic status than Dutch mainstreamers, and also have lower education levels (Vasta 2007). Turkish (and Arab) minority groups are not an invisible minority (like, for instance, many Jewish groups, Altman et al. 2010).

In The Netherlands , acculturation policies are characterized by strong elements of multiculturalism (Crul 2000), but, despite official attempts aiming at an adjustment of immigrant minorities into Dutch society while retaining and preserving their cultural traditions, ethnic minority groups , particularly Muslim groups are still subject to discrimination and prejudice (Boog et al. 2010; Vermeulen and Penninx 2000). For instance, immigrants often describe an identification with both heritage and host culture as being the preferred acculturation strategy (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2004; Mahnig and Wimmer 2000) —but mainstream society and public discourse often exert some pressure for immigrants to adapt to the mainstream society (Crul 2000). In many European countries, immigrants of Arab and Turkish origin face significant prejudice (Saroglou et al. 2009b). Since 2011, overt religious symbols (e.g., veils) are prohibited in public schools in France (see also The Guardian 2011), and are even banned from all public buildings in Belgium. While the discourse found resonance in the public debates in The Netherlands, no legal actions were taken in The Netherlands.

In our study, we focus on the endorsement of religiosity and the acculturation attitudes of second-generation Turkish–Dutch adolescents . We opted for an investigation of an adolescent Turkish–Dutch sample (12–18 years) for several reasons. First, establishing a stable sense of self and self-worth is one of the most salient and pressing developmental tasks during adolescence, and evaluations of one’s own value or the struggle for self-acceptance are among the building blocks of self-esteem (Rosenberg 1986; Ryff 1989). Second, Turkish–Dutch second-generation immigrants are exposed to both cultures to a significant degree, on the one hand the public Dutch host culture (e.g., in educational institutions) and on the other hand the heritage culture, about which they mainly receive information from parents and same-ethnic peers (Chao 1995). Third, for younger children, religious practices and a sense of (religious) belonging seem less important (Holder et al. 2008). Fourth, although there is little direct research on adolescents’ heritage culture orientation, there are studies that indicate that religiosity and family orientation are strongly related. For instance, we know that Turkish (and Moroccan) youth attach high value to heritage culture maintenance, particularly in the family (Güngör et al. 2011; Kosic and Phalet 2006). Also, increasing levels of religiosity are related to better family relations (Regnerus and Burdette 2006). Furthermore, religiosity has a positive impact on family orientation, which in turn is related to increased life satisfaction (Sabatier et al. 2011).

To summarize, religiosity has been shown to be a source of well-being for religious believers when religion is valued in a society (Gebauer et al. 2012). The perceived discrimination and the perceived cultural distance (as experienced by religious believers) suggests that in these scenarios religiosity does not have positive effects. In contrast, there is evidence that stigmatization might lead religious believers to develop depressive symptoms and a lower self-esteem (Friedman and Saroglou 2010). However, this does not hold for all constellations, as heritage culture maintenance and religiosity can lead to a stronger identification with the ethnic community and an increased sense of belonging and self-worth (Saroglou 2011; Verkuyten and Yildiz 2007; see also Branscombe et al. 1999). It is still unclear how the two are related.

We, therefore, set out to identify circumstances under which religiosity and heritage culture maintenance may exert positive effects for second-generation Turkish–Dutch immigrant adolescents . Acculturation orientation and religiosity need to be matched to reap the benefits associated with religiosity and a mismatch or incongruence will lower self-esteem. Adolescents who actively seek to maintain their culture of origin are more likely to experience higher levels of self-esteem when they are also religious.

Methods

Participants

A total of 192 Turkish–Dutch Muslim adolescents participated in the questionnaire study (see Table 1 for details). Participants were recruited as a convenience sample from cities in the southwest of The Netherlands. All participants were second-generation immigrants to The Netherlands.

Procedure

In order to ensure a substantial involvement with the Islam, participants were approached by contacting Muslim organizations (e.g., mosques) as contact multipliers. Contacts were informed that the study is seeking Turkish–Dutch adolescents . Times were arranged for the study to be conducted. On these dates, the second author or a Turkish-speaking student assistant approached the organizations to hand out survey packages. Participants were informed that the survey would not take longer than 20–30 min to fill out and that they should do so alone. Participants were provided with envelopes to seal and send their filled out questionnaires to the researchers.

Material

All questionnaires were made available as a bilingual version containing both Turkish and Dutch, to ensure that participants readily understand the items. While Turkish might represent the participants’ preferred oral language, it is possible that formal schooling may have resulted in a higher proficiency in written Dutch. If not otherwise indicated, scales were translated using a translation back translation procedure from English to Turkish and English to Dutch, respectively. Reverse coded items of all scales were recoded prior to data analysis.

Sociodemographics

Participants were requested to indicate their age, gender , and the number of relatives residing in The Netherlands (to control for the available familial support of participants).

Acculturation Orientation

In order to assess participants’ acculturation attitudes the scale proposed by Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2006; see also Galchenko and Van de Vijver 2007) was applied. The scale includes 29 items, such as “I like to speak in Turkish/Dutch” and “I listen to Turkish/Dutch music in my free time.” Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Two dimensions were assessed, ethnic maintenance and host culture adoption (Arends-Tóth and Van de Vijver 2004). Reliabilities in the present study were 0.88 and 0.83 for culture maintenance and adoption, respectively.

Religiosity

In order to assess the centrality of religion in people’s lives a religiosity scale was adapted from already existing scales, with a focus on selecting items that are not denomination- or religion-specific. Based on results of a pilot study (58 Turkish–Dutch and 58 Dutch participants), in which we adopted a series of religiosity scales, we adapted four items from the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire (Plante et al. 1999), five items from the Religious Orientation Scale (Allport and Ross 1967), one item from the Quest Scale (Batson and Scheonrade 1991), three items from The Multi-religion Identity Measure (Abu-Rayya et al. 2009), one item from the Beliefs and Values Scale (King and Koenig 2009), and one item from the Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (Underwood and Teresi 2002). In addition, we adopted eight items that resulted from a mix of different items from the investigated scales. The resulting scale therefore included 22 items covering aspects about identity, behavior, and attitudes. Participants were requested to indicate their level of endorsement on a 5-point Likert scale (from not applicable to me to applicable to me). The scale proved to be highly reliable in the present study, α = 0.87. All items can be found in the appendix.

Perceived Discrimination

In order to account for feelings of being discriminated against, we used the subscale on discrimination by Schalk-Soekar et al. (2004). The three items were “Sometimes I feel badly treated because of my cultural background,” “Sometimes I have the feeling that I’m not welcome here,” and “Sometimes I feel threatened because I am different compared to the average Dutch person.” Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.68.

Self-Esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (1986) was used to assess participants’ notion of self-worth. The ten items cover both positive (“On the whole I am satisfied with myself”) and negative aspects (“At times, I think I am no good at all”). Participants respond on a 5-point scale (from strongly agree to strongly disagree). For the Turkish version, the scale by Çuhadaroğlu (1986) was used. An alpha of 0.77 was observed for the present study.

Results

To test for possible confounding variables, we compared male and female adolescents . Interestingly, a t-test revealed that female Turkish–Dutch participants felt more discriminated against (M = 1.78; SD = 0.33) than their male counterparts, M = 1.64; SD = 0.36; t(189) = − 2.59; p = 0.001. It is noteworthy that the sample did not seem to feel overly discriminated (a score of 1.70 on a 5-point scale, Table 1). Furthermore, female participants were marginally more oriented toward maintaining their culture of origin (M = 4.07; SD = 0.62) than male individuals in the study, M = 3.90; SD = 0.64; t(190) = − 1.86; p = 0.064. No other differences between the genders were observed. Gender was partialed out for the intercorrelations as far as perceived discrimination is concerned (see Table 2).

An inspection of the intercorrelations of the variables reveals that the relationships are generally in line with the literature on acculturation. Feeling discriminated is marginally associated with a decreased adoption orientation. A strong maintenance orientation, as well as a high level of religiosity is associated with a decreased adoption orientation. In line with literature on positive distinctiveness (Verkuyten 2007), self-esteem is correlated positively with a maintenance orientation. Religiosity, in turn, is strongly related to a maintenance orientation. It is also interesting to note that in our sample, participants endorsed a maintenance acculturation orientation more strongly than an adoption acculturation orientation, t(192) = 15.42; p < 0.001. In subsequent analyses, we controlled for age as well as the number of family members in The Netherlands , as that showed relationships with some of the target variables, and we were not interested in the effects of the support network of our participants or specific differences within adolescence (see Table 2).

To investigate whether maintaining the parental culture (or adapting to the mainstream culture) and religiosity influence experienced self-esteem, we conducted linear regression analyses. To account for the size of the familial support network available to participants, the number of family members in The Netherlands was entered into the first block of the regression. The predictors (acculturation orientations, religiosity) were then included in block two and their interaction terms (computed by multiplication) in block three.

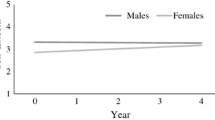

We observed in block two that maintaining the parental culture had a significant effect on self-esteem , while host culture adoption was unrelated to self-esteem. Interestingly, religiosity had a marginally significant negative effect on self-esteem. However, these main effects disappeared upon including the interaction effects in block three, particularly the effect of maintenance and religiosity on self-esteem (see Table 3; Fig. 1). No other two-way interactions were significant.

Simple slope tests were computed to identify the direction of the interaction effect between culture maintenance and religiosity (see Cohen et al. 2003; O’Connor 1998), revealing that slopes corresponding to a low maintenance acculturation orientation (t(192) = − 2.38; p = 0.018) differ significantly from zero. No differences in self-esteem were found for individuals with medium or high maintenance acculturation orientation. The findings indicate that a mismatch between religiosity and heritage culture maintenance is harmful: Among individuals who strongly endorse their religious beliefs, self-esteem suffers when they do not maintain their heritage culture much—but not when they at least moderately maintain their culture of origin.

Discussion

Members of oppressed ethnic minorities typically experience low levels of psychological well-being (Verkuyten 2005). Since religiosity is often associated with psychological benefits, it therefore seemed worthwhile to investigate its role in an acculturation context. We set out to investigate under which conditions Turkish–Dutch adolescent individuals may profit from a match in their acculturation orientations and their degree of religiosity. We expected that a match would be conducive for self-esteem , while a mismatch between the two would be accompanied by decreased self-esteem. We did not find support for the first prediction, but we found evidence that when religiosity is endorsed—but not heritage culture maintenance—the self-esteem of the second-generation Turkish–Dutch adolescents in our sample is significantly reduced.

We did not find any relationships with regard to the adoption orientation of participants. Participants in our sample endorsed an adoption orientation generally less than a maintenance acculturation, but the average adoption score was still not low, and close to the midpoint of the scale. The absence of findings with regard to adoption attitudes is in line with other European studies that do not show any relationship between religiosity and adoption acculturation values among immigrant groups (including Turkish or North-African Muslims; Friedman and Saroglou 2010; Güngör et al. 2011; Saroglou and Galand 2004; Saroglou and Mathijsen 2007; Verkuyten and Yildiz 2007).

Dutch majority group members often view heritage culture maintenance as a threat to the Dutch cultural cohesion (Van Oudenhoven et al. 1998), particularly when the Turkish ethnic minority is concerned (Arends-Tóth and Van De Vijver 2003). With such majority group attitudes, it is not surprising that perceived discrimination is important for the formation of minority group members’ attitudes and values. On the one hand, positive psychological effects might be expected, as such adversity may lead people to attach more strongly to their ethnic culture (Awad 2010), but such effects have been shown to not automatically result from experiencing discrimination (Lee et al. 2007). A previous study (Friedman and Saroglou 2010) has found an indirect effect of religiosity on the adoption orientation in such a fashion that perceived discrimination mediates the relationship between religiosity and an adoption orientation. In our study, we only found a marginal, direct, and negative effect of perceived discrimination on adoption orientation. However, this effect would need to be interpreted with caution, as the levels of discrimination perceived by the sample were very low, and there was not much variance in our data. It would be interesting to see how a sample would fare that feels more discriminated against. The generally low levels of discrimination might be responsible for the absence of any other discrimination-related findings in our study with regard to the mediation effect obtained by Friedman and Saroglou (2010).

Limitations

There are several limitations that qualify our findings and outline avenues for improvement and expansion. First of all, we approached our sample via religious organizations (e.g., mosques). This invites a highly self-selected body of participants. Adolescents that are attending religious services in a somewhat regular manner represent only a subsample of Turkish–Dutch adolescents . While it served our purposes to ensure that the sample was at least moderately religious, our findings therefore cannot be generalized to Turkish–Dutch adolescents as a whole (but see Güngör et al. 2012). For the specific context of those adolescents that focus on their religiosity (as signified by their mosque attendance and high scores on religiosity), we can conclude that an alignment of religiosity and acculturation orientation is important for self-esteem.

Second, our findings are restricted to self-report scales, which allow for a relatively limited insight into the actual psychological processes involved in the acculturative process. For instance, Chirkov (2009) argues that such standardized scales are flawed and advocates the use of multimethod and qualitative approaches, such as ethnography, participant observations, and qualitative interviewing (see also Stuart and Ward 2011).

Finally, we did not differentiate between facets of religiosity , for instance between extrinsic or intrinsic religiosity (Allport and Ross 1967), or between more recent classifications of different functions such as believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging which are assumed to reflect distinct psychological processes (i.e., cognitive, emotional, moral, and social processes, respectively, see Saroglou 2011). It could be argued that the bonding and belonging function might be most prevalent for the coping purposes of immigrants (Saroglou 2011). Future studies could focus more on how such specific aspects of religiosity, in conjunction with acculturation orientations, contribute to—or hinder—positive psychological outcomes in the acculturative process. At the same time, however, it needs to be noted that there is also strong evidence for the presence of a higher-order unidimensional factor of religiosity which has provided solid findings, often constant across studies, religions, and cultural contexts (see Saroglou and Cohen 2013, for a review).

Perspective and Conclusion

The sample investigated in our study is not representative for Turkish–Dutch second-generation adolescents in The Netherlands , because our participants’ religious endorsement and a heritage culture maintenance orientation were close to the end points of the self-report scales we used. However, we also see that host culture adoption is not low, but can be found at or around the midpoint of the scale we used. Finding this among a strongly maintenance-oriented group of adolescents suggests that issues of balancing cultural demands and negotiating cultural belongingness occurs between family, friends, the Muslim community, and the wider society (see Stuart and Ward 2011). It might well be that due to our sample recruitment via religious organizations we prompted people to approach their acculturative process from a heritage culture perspective—responses might have been different if participants were approached as part of a larger study in a Dutch University lecture hall. In other words, it might be useful to consider the dynamic component of acculturation and religiosity more explicitly in future studies. It has previously been shown that already children can alternate between different cultural sets when presented with a frame-switching procedure (Verkuyten and Pouliasi 2002; Maykel Verkuyten and Pouliasi 2006). An aspect that could play a particularly important role is the perception of conflict between the cultures that an individual navigates (Benet-Martinez et al. 2002; Hong et al. 2000). Furthermore, Saroglou et al. could also show that religious priming affected participants (Saroglou et al. 2009a; Van Cappellen et al. 2011). Understanding how individuals react differently depending on the cultural—and religious—salience of the context would help us in better understanding an integration orientation (the combination of both adoption and maintenance). This resonates with recent efforts to provide a more sophisticated analysis of integration and operationalize it as a dynamic construct with different facets (Boski 2008; Ward 2013). Such efforts would more clearly help in considering both adoption and maintenance attitudes, depending on the context.

To conclude, we have set out against the premise that for majority group members, religiosity is accompanied by positive psychological effects—under the condition that religion is societally valued (Gebauer et al. 2012). For Turkish immigrants, a European acculturation scenario arguably presents a context in which their religious faith is perceived as culturally distant or even discriminated against, particularly since 9/11 (Sheridan 2006). However, religiosity does not necessarily have to be accompanied by negative effects. We have identified that only when religiosity is not aligned with a clear heritage culture maintenance orientation, the self-esteem of the relatively religious second-generation Turkish–Dutch adolescents in our sample suffers. We take this as an indication that acculturative outcomes need to be differentiated and depend on the immediate personal context of the acculturating individual.

References

Abu-Rayya, H. M., Abu-Rayya, M. H., & Khalil, M. (2009). The Multi-Religion Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse religions. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 4, 124–138.

Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 432–443.

Altman, A. N., Inman, A. G., Fine, S. G., Ritter, H. A., & Howard, E. E. (2010). Exploration of Jewish ethnic identity. Journal of Counseling & Development, 88, 163–173.

Arends-Tóth, J.V., & Van De Vijver, F. J. R. (2003). Multiculturalism and acculturation: Views of Dutch and Turkish-Dutch. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 249–266.

Arends-Tóth, J. V., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2004). Domains and dimensions in acculturation: Implicit theories of Turkish-Dutch. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28, 19–35.

Arends-Tóth, J. V., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2006). Issues in conceptualization and assessment of acculturation. In M. H. Bornstein, & L. R. Cote (Eds.), Acculturation and parent-child relationships: Measurement and development (pp. 33–62). Mahwah, NJ US: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Arends-Tóth, J. V., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2009). Cultural differences in family, marital, and gender-role values among immigrants and majority members in the Netherlands. International Journal of Psychology, 44, 161–169.

Argyle, M. (2001). The psychology of happiness (2nd ed.). New York, NY US: Routledge.

Awad, G. H. (2010). The impact of acculturation and religious identification on perceived discrimination for Arab/Middle Eastern Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 59–67.

Aydin, N., Fischer, P., & Frey, D. (2010). Turning to God in the face of ostracism: Effects of social exclusion on religiousness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 742–753.

Bankston, C. L. (1997). Bayou lotus: Theravada Buddhism in Southwestern Louisiana. Sociological Spectrum, 17, 453–472.

Batson, C. D., & Scheonrade, P. (1991). Measuring religion as quest: Reliability concerns. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 430–447.

Beirens, K., & Fontaine, J. R. J. (2011). Somatic and emotional well-being among Turkish immigrants in Belgium: Acculturation or culture? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 56–74.

Benet-Martinez, V., Leu, J. X., Lee, F., & Morris, M. W. (2002). Negotiating biculturalism—Cultural frame switching in biculturals with oppositional versus compatible cultural identities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33, 492–516.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46, 5–34.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 55, 303–332.

Boog, I., Dinsbach, W., Van Donselaar, J., & Rodrigues, P. R. (2010). Monitor Rassendiscriminatie 2009 (Monitor race discrimination 2009). Rotterdam: Landelijk expertisecentrum van Art. 1.

Boski, P. (2008). Five meanings of integration in acculturation research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32, 142–153.

Branscombe, N., Schmitt, M., & Harvey, R. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149.

Cadge, W., & Ecklund, E. H. (2007). Immigration and religion. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 359–79.

Chao, R. K. (1995). Chinese and European American cultural models of the self reflected in mothers’ childrearing beliefs. Ethos, 23, 328–354.

Chattopadhyay, S. (2007). Religion, spirituality, health and medicine: Why should Indian physicians care? Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 53, 262–6.

Cheung, C., & Yeung, J. W. (2011). Meta-analysis of relationships between religiosity and constructive and destructive behaviors among adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 376–385.

Chirkov, V. (2009). Critical psychology of acculturation: What do we study and how do we study it, when we investigate acculturation? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33, 94–105.

Cohen, A. B. (2009). Many forms of culture. American Psychologist, 64, 194–204.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Crul, M. (2000). De sleutel tot succes (The key to success). Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis.

Crul, M., & Doomernik, J. (2003). The Turkish and Moroccan second-generation in the Netherlands: Divergent trends between and polarization within the two groups. International Migration Review, 37, 1039–1064.

Çuhadaroğlu, F. (1986). Adolesanlarda benlik saygısı (Self-esteem in adolescence). Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey.

Dimitrova, R., Chasiotis, A., Bender, M., & Van de Vijver, F. (2012). Collective identity and wellbeing of Roma minority adolescents in Bulgaria. International Journal of Psychology, 48, 1–12.

Droogsma, R. A. (2007). Redefining hijab: American Muslim women’s standpoints on veiling. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 35, 294–319.

Ebaugh, H. R., Chafetz, J. S. (Eds.). (2000). Religion and the new immigrants: Continuities and adaptations in immigrant congregations. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira.

Emmons, R. A., & Paloutzian, R. F. (2003). The psychology of religion. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 377–402.

Foner, N., & Alba, R. (2008). Immigrant religion in the U.S. and Western Europe: Bridge or barrier to inclusion? International Migration Review, 42, 360–392.

Friedman, M., & Saroglou, V. (2010). Religiosity, psychological acculturation to the host culture, self-esteem and depressive symptoms among stigmatized and nonstigmatized religious immigrant groups in Western Europe. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 32, 185–195.

Galchenko, I., & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2007). The role of perceived cultural distance in the acculturation of exchange students in Russia. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31, 181–197.

Gebauer, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Neberich, W. (2012). Religiosity, social self-esteem, and psychological adjustment: On the cross-cultural specificity of the psychological benefits of religiosity. Psychological Science, 23, 158–160.

Güngör, D., Fleischmann, F., & Phalet, K. (2011). Religious identification, beliefs, and practices among Turkish Belgian and Moroccan Belgian Muslims: Intergenerational continuity and acculturative change. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 1356–1374.

Güngör, D., Bornstein, M. H., & Phalet, K. (2012). Religiosity, values, and acculturation: A study of Turkish, Turkish Belgian, and Belgian adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 36, 367–373.

Harker, K. (2001). Immigrant generation, assimilation, and adolescent psychological well-being. Social Forces, 79, 969–1004.

Holder, M. D., Coleman, B., & Wallace, J. M. (2008). Spirituality, religiousness, and happiness in children aged 8–12 Years. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 131–150.

Hong, Y., Morris, M. W., Chiu, C., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2000). Multicultural minds: A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. American Psychologist, 55, 709–720.

Hood, R. W. J., Hill, P. C., & Spilka, B. (2009). The psychology of religion: An empirical approach (4th ed.). New York, NY US: Guilford Press.

Houskamp, B. M., Fisher, L. A., & Stuber, M. L. (2004). Spirituality in children and adolescents: research findings and implications for clinicians and researchers. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 13, 221–30.

Juang, L. P., & Syed, M. (2008). Ethnic identity and spirituality. In R. Lerner, R. W. Roeser, & E. Phelps (Eds.), Positive youth development and spirituality: From theory to research (pp. 262–284). West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press.

King, M. B., & Koenig, H. G. (2009). Conceptualizing spirituality for medical research and health service provision. BMC Health Services Research, 9, 1–7.

King, P. E., & Roeser, R. (2009). Religion & spirituality in adolescent development. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology, 3 rd Edition, Volume 1: Development, relationships and research methods. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Koenig, H. G., King, D. E., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed.). New York, NY US: Oxford University Press.

Kosic, A., & Phalet, K. (2006). Ethnic categorization of immigrants: The role of prejudice, perceived acculturation strategies and group size. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30, 769–782.

Lee, R. M., Noh, C. Y., Yoo, H. C., & Doh, H. S. (2007). The psychology of diaspora experiences: Intergroup contact, perceived discrimination, and the ethnic identity of Koreans in China. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 115–124.

Lehman, D. R., Chiu, C., & Schaller, M. (2004). Psychology and culture. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 689–714.

Leondari, A., & Gialamas, V. (2009). Religiosity and psychological well-being. International Journal of Psychology, 44, 241–248.

Lonner, W. J. (2011). Editorial introduction and commentary. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 1303–1308.

Mahnig, H., & Wimmer, A. (2000). Country-specific or convergent? A typology of immigrant policies in Western Europe. Journal of International Migration and Integration/Revue de l’integration et de la migration internationale, 1, 177–204.

Matsumoto, D., & Juang, L. (2008). Culture and psychology (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Myers, S. M. (1996). An interactive model of religiosity inheritance: The importance of family context. American Sociological Review, 61, 858–866.

O’Connor, B. P. (1998). SIMPLE: All-in-one programs for exploring interactions in moderated multiple regression. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58, 836–840.

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. (2010). Religiosity and life satisfaction across nations. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 13, 155–169.

Phinney, J. S., Cantu, C., & Kurtz, D. (1997). Ethnic and American identity as predictors of self-esteem among African American, Latino, and White adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26, 165–185.

Phinney, J. S., Horenczyk, G., Liebkind, K., & Vedder, P. (2001). Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 493–510.

Plante, T., Yancey, S., Sherman, A., Guertin, M., & Pardini, D. (1999). Further validation for the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire. Pastoral Psychology, 48, 11–21.

Regnerus, M. D., & Burdette, A. (2006). Religious change and adolescent family dynamics. The Sociological Quarterly, 47, 175–194.

Rivadeneyra, R., Ward, L. M., & Gordon, M. (2007). Distorted reflections: Media exposure and Latino adolescents’ conceptions of self. Media Psychology, 9, 261–290.

Rosenberg, M. (1986). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books.

Ryder, A. G., Alden, L. E., & Paulhus, D. L. (2000). Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 49–65.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Sabatier, C., Mayer, B., Friedlmeier, M., Lubiewska, K., & Trommsdorff, G. (2011). Religiosity, family orientation, and life satisfaction of adolescents in four countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 1375–1393.

Sam, D. L. (2006). Acculturation: Conceptual background and core components. In D. L. Sam & J. W. Berry (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 11–26). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sam, D., & Berry, J. W. (Eds.). (2006). Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Saroglou, V. (2011). Believing, bonding, behaving, and belonging: The Big Four Religious Dimensions and cultural variation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 1320–1340.

Saroglou, V. (2012). Adolescents’ social development and the role of religion: Coherence at the detriment of openness. In G. Trommsdorff, & X. Chen (Eds.), Values, religion, and culture in adolescent development (pp. 391–423). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Saroglou, V., & Cohen, A. B. (2013). Cultural and cross-cultural psychology of religion. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (2nd ed., pp. 330–353). New York: Guilford Press.

Saroglou, V., & Galand, P. (2004). Identities, values, and religion: A study among Muslim, other immigrant, and native Belgian young adults after the 9/11 attacks. Identity, 4, 97–132.

Saroglou, V., & Mathijsen, F. (2007). Religion, multiple identities, and acculturation: A study of Muslim immigrants in Belgium. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 29, 177–198.

Saroglou, V., Corneille, O., & Van Cappellen, P. (2009a). “Speak, Lord, your servant is listening”: Religious priming activates submissive thoughts and behaviors. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19, 143–154.

Saroglou, V., Lamkaddem, B., Van Pachterbeke, M., & Buxant, C. (2009b). Host society’s dislike of the Islamic veil: The role of subtle prejudice, values, and religion. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33, 419–428.

Schalk-Soekar, S. R. G. G., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Hoogsteder, M. (2004). Attitudes toward multiculturalism of immigrants and majority members in the Netherlands. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 28, 533–550.

Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Weisskirch, R. S., & Rodriguez, L. (2009). The relationships of personal and ethnic identity exploration to indices of adaptive and maladaptive psychosocial functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33, 131–144.

Sedikides, C. (2010). Why does religiosity persist? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 3–6.

Sedikides, C., & Gebauer, J. E. (2010). Religiosity as self-enhancement: A meta-analysis of the relation between socially desirable responding and religiosity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 17–36.

Sheridan, L. P. (2006). Islamophobia pre- and post-September 11th, 2001. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 317–336.

Sirin, S. R., & Fine, M. (2007). Hyphenated selves: Muslim American youth negotiating identities on the fault lines of global conflict. Applied Developmental Science, 11, 151–163.

Smith, T. B., McCullough, M. E., & Poll, J. (2003). Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 614–636.

Smith, T. B., & Silva, L. (2011). Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 42–60.

Strawbridge, W. J., Cohen, R. D., Shema, S. J., & Kaplan, G. A. (1997). Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 957–961.

Stuart, J., & Ward, C. (2011). Question of balance: Exploring the acculturation, integration and adaptation of Muslim immigrant youth. Psychosocial Intervention, 20, 255–267.

The Guardian. (2011). France’s burqa ban: Women are ‘effectively under house arrest’. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/sep/19/battle-for-the-burqa?intcmp=239. Accessed 19 Sep 2011.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. New York: Blackwell.

Underwood, L., & Teresi, J. (2002). The daily spiritual experience scale: development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 22–33.

Van Cappellen, P., Corneille, O., Cols, S., & Saroglou, V. (2011). Beyond mere compliance to authoritative figures: Religious priming increases conformity to informational influence among submissive people. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 21, 97–105.

Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2009). The role of ethnic hierarchies in acculturation and intergroup relations. In I. Jasinskaja-Lahti & T. A. Mahonen (Eds.), Identities, intergroup relations and acculturation. The cornerstones of intercultural encounters (pp. 165–178). Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Phalet, K. (2004). Assessment in multicultural groups: The role of acculturation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53, 215–236.

Van Oudenhoven, J. P., Prins, K. S., & Buunk, B. P. (1998). Attitudes of minority and majority members towards adaptation of immigrants. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28, 995–1013.

Van Zomeren, M., Spears, R., & Leach, C. W. (2008). Exploring psychological mechanisms of collective action: Does relevance of group identity influence how people cope with collective disadvantage? British Journal of Social Psychology, 47, 353–372.

Vasta, E. (2007). From ethnic minorities to ethnic majority policy: Multiculturalism and the shift to assimilationism in the Netherlands. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30, 713–740.

Verkuyten, M. (2005). The social psychology of ethnic identity. Hove: Psychology Press.

Verkuyten, M. (2007). Religious group identification and inter-religious relations: A study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 10, 341–357.

Verkuyten, M., & Pouliasi, K. (2002). Biculturalism among older children: Cultural frame switching, attributions, self-identification, and attitudes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33, 596–609.

Verkuyten, M., & Pouliasi, K. (2006). Biculturalism and group identification: The mediating role of identification in cultural frame switching. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 312–326.

Verkuyten, M., & Yildiz, A. A. (2007). National (dis)identification and ethnic and religious identity: a study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1448–1462.

Vermeulen, H., & Penninx, R. (Eds.) (2000). Immigrant integration: The Dutch case. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis.

Viladrich, A., & Abraido-Lanza, A. F. (2009). Religion and mental health among minorities and immigrants in the U.S. In S. Loue & M. Sajatovic (Eds.), Determinants of minority mental health and wellness (pp. 149–174). New York: Springer.

Voas, D., & Crockett, A. (2005). Religion in Britain: Neither believing nor belonging. Sociology, 39, 11–28.

Ward, C. (2001). The A, B, Cs of Acculturation. In D. Matsumoto (Ed.), The handbook of culture and psychology (pp. 411–445). New York, NY US: Oxford University Press.

Ward, C. (2013). Probing identity, integration and adaptation: Big questions, little answers. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37, 391–404.

Warner, R. S., & Wittner, J. G. (Eds.). (1998). Gatherings in diaspora: Religious communities and the new immigration. Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Press.

Whittaker, S., Hardy, G., Lewis, K., & Buchan, L. (2005). An exploration of psychological well-being with young Somali refugee and asylum-seeker women. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 10, 177–196.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

SCSoRFQ Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire (Plante et al. 1999), ROS Religious Orientation Scale (Allport and Ross 1967), QS Quest Scale (Batson and Scheonrade 1991), MRIM Multi-religion Identity Measure (Abu-Rayya et al. 2009), BaVS Beliefs and Values Scale (King and Koenig 2009), DSES Daily Spiritual Experiences Scale (Underwood and Teresi 2002), [rc] reverse coded items

Appendix

Religiosity scale

-

1.

I look to my faith as providing meaning and purpose in my life (SCSoRFQ).

-

2.

I enjoy being around others who share my faith (SCSoRFQ).

-

3.

I look to my faith as a source of comfort (SCSoRFQ).

-

4.

My faith impacts many of my decisions (SCSoRFQ).

-

5.

There are many more important things in life than religion (ROS). [rc]

-

6.

I pray because I have been taught to pray (ROS).

-

7.

I read literature about my faith (ROS).

-

8.

I sometimes compromise my faith for social/economic reasons (ROS). [rc]

-

9.

Private religious thoughts and meditation is important to me (ROS).

-

10.

I do not expect my religious convictions to change in the next few years (original); I expect my religious convictions to change in the next few years (amended version) (QS).

-

11.

My religion confuses me (MRIM). [rc]

-

12.

I have not found for myself a satisfying lifestyle which is based on my religion (MRIM). [rc]

-

13.

I feel an attachment toward my religion (MRIM).

-

14.

I believe in life after death (BaVS).

-

15.

I feel thankful for my blessings (DSES).

-

16.

When people talk about my religion, I feel as if they talk about me.

-

17.

When I take decisions in my daily life, I consider the rules of my faith.

-

18.

Whatever happens, my faith will remain an important part of my life.

-

19.

I pray when I am alone.

-

20.

I live my life in accordance with the rules of my religion.

-

21.

I only focus on my faith when I seek comfort. [rc]

-

22.

Religious symbols support my faith.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bender, M., Yeresyan, I. (2014). The Importance of Religiosity and Cultural Maintenance for Self-Esteem: The Case of Second-Generation Turkish–Dutch Adolescents. In: Dimitrova, R., Bender, M., van de Vijver, F. (eds) Global Perspectives on Well-Being in Immigrant Families. Advances in Immigrant Family Research, vol 1. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9129-3_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9129-3_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-9128-6

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-9129-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)