Abstract

In line with the Positive Youth Development (PYD) framework positing that religion provides youth with resources to thrive, this chapter presents a contribution analyzing associations between religiosity and well-being among middle and late adolescents and emerging adults in Italy. Italy is a unique context to study this topic due to societal relevance and historical presence of Catholicism. We conceptualized religiosity as religious commitment and well-being as life satisfaction and focused on the mediating role of optimism between these two constructs. A multiple-group path model revealed a direct invariant link between religious commitment and life satisfaction as well as a significant mediating role of optimism in middle adolescents and emerging adults, but not in late adolescents. Conclusions afford implications about why and how religiosity and optimism contribute to PYD in cultural contexts like Italy.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Theoretical Framework and Main Questions

Religiosity, in terms of adherence to religious rituals, values and practices of an institutionalized doctrine (Hill et al., 2000), has been linked to satisfaction with life as a relevant dimension of youth’s subjective well-being (Abdel-Khalek, 2012; Kelley & Miller, 2007; King & Roeser, 2009; Yonker, Schnabelrauch, & DeHaan, 2012). However, scholars have questioned direct associations between one’s religiosity and life satisfaction by arguing that other social and cognitive factors might mediate such relationship (Hayward & Krause, 2014). In the attempt to shed light on the mechanisms by which religiosity can exert its salubrious effect on life satisfaction, some researchers tested models whereby religiosity influences life satisfaction by way of optimism (e.g., Salsman, Brown, Brechting, & Carlson, 2005). In fact, optimism, as a tendency to expect good things in life (Carver & Scheier, 2014), may be both a predictor of satisfaction with life (Mishra, 2013) and a positive outcome of religiosity (Krause, 2002). These potential relationships are partly suggested by recent researches. For instance, Zeb, Riaz, and Jahangir (2015) showed that religiosity , but not optimism, was a positive predictor of mental health . Moreover, Ferguson and Goodwin (2010) found that optimism is positively associated with both subjective and psychological well-being. Although these studies refer to a broader view of well-being, it may be that a similar set of associations is applicable also in the more specific domain of the satisfaction with life. However, further research is needed in the field. In fact, despite the increasing interest of scholars, little is known about the structural relationships amongst religiosity , optimism, and life satisfaction, especially during the passage from adolescence to emerging adulthood .

On the basis of these premises, this chapter presents a study aimed at testing a mediation model whereby religiosity predicted satisfaction with life both directly and by way of optimism in adolescents and emerging adults . The study was framed within the Positive Youth Development perspective (PYD ; Lerner, Lerner, von Eye, Bowers, & Bizan-Lewin, 2011) positing religion as a significant ideological and social resource that promotes young people ’s successful growth (King & Roeser, 2009). In fact, not only religion serves as a meaning-making system helping youth answer existential questions and orient their lives, but it also provides them with worldviews, values, beliefs, and social support , guiding them in the ages of transition from adolescence to adulthood (Barry & Abo-Zena, 2014).

Religiosity, Well-Being, and the Mediating Role of Optimism

Empirical evidence suggests that religiosity is positively associated with psychological well-being of adolescents and emerging adults (e.g., Barry, Nelson, Davarya, & Urry, 2010; Furrow, King, & White, 2004; Kirk & Lewis, 2013; Yonker et al., 2012). Particularly, religiosity was shown to be positively linked to life satisfaction (Abdel-Khalek, 2012; Kelley & Miler, 2007), considered as the conscious cognitive judgment of one’s personal well-being (Pavot & Diener, 1993). However, scholars have questioned the direct influence of religiosity on life satisfaction, reporting that religiosity might also work in conjunction with other socio-cultural, cognitive, and individual variables (Hayward & Krause, 2014; Van Cappellen, Toth-Gauthier, Saroglou, & Fredrickson, 2016). For instance, Sabatier, Mayer, Friedlmeier, Lubiewska, and Trommsdorff (2011) showed that religiosity promotes family relationship values and family interdependence (i.e., family orientation) among adolescents, which in turn enhances their satisfaction with life. Moreover, they highlighted that such links are stronger in high religious countries than in secular ones. Also, Steger and Frazier (2005) reported that religiousness provides young adults with meaning in their lives which, in turn, increases their well-being and psychological health. Nonetheless, more research is needed to explain how and why religiosity can exert its beneficial effects on well-being among adolescents and emerging adults.

In order to clarify this mechanism, it is possible to consider the mediating role of optimism. Indeed, studies have found that optimism is positively linked with markers of psychological well-being, such as life satisfaction, sense of meaning in life, and overall quality of life (Ho, Cheung, & Cheung, 2010; Mishra, 2013), and acts as a positive outcome of religiosity (Krause, 2002). Relatedly, research by Salsman et al. (2005) found that religiousness and prayer fulfillment is associated with satisfaction with life through optimism among emerging adults. However, further studies are needed to take into account the developmental changes youth undergo in the passage from adolescence to adulthood . In fact, this transition period is a time of both great opportunities and vulnerabilities (Dahl, 2004; Kirk & Lewis, 2013), during which religiosity has been shown to play a salient role in protecting individuals against mental illness (e.g., depression, Pearce, Little, & Perez, 2003) and health-risk behaviors (e.g., alcohol use; Jankowski, Hardy, Zamboanga, & Ham, 2013). Also, it prevents destructive behaviors such as violence (Salas-Wright, Vaughn, & Maynard, 2014), delinquency (Johnson, Jang, Larson, & Li, 2001), and aggression (Hardy, Walker, Rackham, & Olsen, 2012). As abundant research pointed out, there are several possible explanations about why religiosity promotes positive youth development (King & Boyatzis, 2015). To mention one, faith based organizations provide adolescents with a set of beliefs and values guiding them during their growth, and exert a certain extent of social control, in terms of moral and normative behaviors (King, 2003).

Relationships Between Religiosity, Optimism , and Life Satisfaction in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood

Adolescence (approximately from 14 to 19 years old) and emerging adulthood (approximately from 20 to 30 year old) are two critical phases in the life cycle. The former is a period of transition from childhood to adult roles marked by puberty and self-concept formation (Dahl, 2004), while the latter bridges adolescence and adulthood through a protracted exploration and construction of one’s identity (Arnett, 2014 ). Abundant research underlined that adolescents and emerging adults experience religion in different ways (Barry et al., 2010; Chan, Tsai, & Fuligni, 2015). During early and middle adolescence , individuals’ images of God begin to be more abstract, internalized and personal than in childhood , but their religious beliefs are still not critically articulated and, to some extent, conform to the ones inherited from parents (Fowler & Dell, 2006). Differently, during the transition from high school to college, adolescents possess a greater set of cognitive capacities helping them to reflect on different aspects of the self and on the culture they live in (Zarrett & Eccles, 2006). As a consequence, they start to search for a beliefs system consistent with the values they have accumulated (Steinberg, 1999). Once they age into emerging adulthood , individuals tend to disaffiliate from religious practices and communities, and to show a greater interest in exploring their religious identities . This is mainly due to their advancement in pragmatic and rational thinking, to their willingness to be self-sufficient and to form their own beliefs. At this phase, religiosity becomes a private concern, often characterized by mistrust of religious institutions (Arnett & Jensen, 2002; Barry et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2015).

In light of these developmental changes , it is reasonable to suppose that the links among religiosity , optimism, and life satisfaction may change with age according to differences in the ways of experiencing religion. For instance, given that younger adolescents might hold more idealized representations of God as a supporting entity (Fowler & Dell, 2006), they may tend to be more optimistic about life when religiosity is a salient dimension. Contrary, late adolescents may report weaker associations with optimism because of their more probing approach to religiosity , which may not be necessarily seen as something that gives security and positive expectations for the future. In emerging adulthood , instead, the relationships among religiosity , optimism and life satisfaction may be strengthened, since religiosity is now experienced in a more private, individualized way (Magyar-Russel, Deal, & Brown, 2014). Unfortunately, to date, to best of our knowledge, there is no empirical research investigating age related trends in the associations between religiosity , optimism and life satisfaction. Thus, the novel aspect of our study is to fill in this gap. In doing so, we also explored how these associations occur in a particular cultural context like Italy . This is a relevant point considering that culture may play a key role in the association between religiosity and well-being (Diener, Tay, & Myers, 2011).

Context and Cultural Distinctiveness of the Study Sample

Some studies have found that religiosity affects both happiness and life satisfaction of people from different cultures (e.g., Graham & Crown, 2014). However, it might be that religiosity would have a greater effect on people living in countries characterized by a long religious tradition because in these contexts conventional beliefs may act as an anchorage offering security and certainty (Garelli, 2013). For this reason, Italy represents an important context for studying this topic, given that Catholicism is a very influential and salient cultural feature of this country because of social and historical reasons. In fact, differently from other European countries, especially the Northern ones, in Italy young people continue to grow up in a society strongly marked by a long-established religious culture (Garelli, 2007, 2013).

A close look to recent surveys reveals that 62% of Italians declare to be practicing Catholicism , whereas 38% to be non-practicing. With regards to young population, statistics show that 68% of people between 15 and 34 years of age define themselves as Catholic (Doxa, 2014). Nevertheless, this does not means that other youth are unconnected with Catholic religion and its customs because, as noted by Bader, Baker, and Molle (2012), in Italy a form also exists of Catholic religious belonging that is culturally inherited rather than profoundly experienced and manifestly expressed. Also, in the last years Italy is facing a difficult social and economic crisis (e.g., unemployment, limited social policies ) which may disorient youth, increase uncertainty toward the future, and negatively affect their well-being (Crocetti, Rabaglietti, & Sica, 2012; Karaś, Cieciuch, Negru, & Crocetti, 2015). In such a context, religiosity may represent a resource for young people to enhance their life satisfaction both directly and indirectly by way of optimism in line with our previous arguments and PYD predictions. Notwithstanding this background, in Italy there is a delay on investigating this topic, compared to other countries like the United States. This lack of studies hinders comparisons between the Italian and other contexts (Laudadio & D’Alessio, 2010) that could be particularly informative about the role of culture in the associations between religiosity and positive functioning of youth.

The Present Study

On the basis of previous research (e.g., Salsman et al., 2005), as well as on the need of a deeper understanding of how religiosity , optimism and life satisfaction relate during adolescence and emerging adulthood , the purpose of the present contribution was to test a partial mediation model (see Fig. 1) whereby religiosity is associated with life satisfaction also by way of optimism in three age groups (middle adolescents, late adolescents, and emerging adults). We conceptualized religiosity in terms of religious commitment that is “the degree to which a person adheres to his or her religious values , beliefs , and practices and uses them in daily living” (Worthington et al., 2003, p. 85). Optimism was conceived as a mental attitude consisting of the tendency to expect good things in life (Carver & Scheier, 2014). Satisfaction with life was defined in terms of judgments individuals make about how much their life, as a whole, is good (Pavot & Diener, 1993). In particular, we tested the following hypotheses.

-

H1. Religiosity is positively associated with life satisfaction in all age groups.

-

H2. Religiosity is more positively associated with optimism in middle adolescents and emerging adults than in late adolescents.

-

H3. Optimism is positively associated with life satisfaction in all age groups.

-

H4. Optimism has a more relevant mediating role in the relationship between religiosity and life satisfaction in middle adolescents and emerging adults than in late adolescents.

Unique contribution of this study is that it is one of the first to test a clear theoretical model of the joint and relative role of religiosity and optimism in promoting Italian adolescents’ and emerging adults’ well-being, in terms of life-satisfaction. Moreover, it is the first study to examine these relationships in a cross-sectional developmental study in the Italian context.

Method

Sample and Procedures

Participants were 164 individuals in middle adolescence (146 girls), 131 individuals in late adolescence (109 girls), and 167 individuals in emerging adulthood (153 girls) of Italian origin and living in Palermo , one of the largest cities in Southern Italy . The middle adolescence group included ninth through tenth graders attending Italian high schools. The participants’ age of this group ranged from 14 to 16 years (M = 14.78, SD = 0.84). In terms of religious affiliation , the majority of participants declared to be Christian (78%). Seventy-three percent of their mothers and 72% of their fathers had at least a high school education. The late adolescence group included 12th through 13th graders attending Italian high schools. The participants’ age of this group ranged from 17 to 19 years (M = 17.85, SD = 0.82). In terms of religious affiliation , the majority of participants declared to be Christian (72%). Fifty-eight percent of their mothers and 61% of their fathers had at least a high school education. The emerging adulthood group included undergraduate students attending social sciences classes at the University of Palermo. The participants’ age of this group ranged from 20 to 30 years (M = 22.10, SD = 1.88). In terms of religious affiliation , the majority of participants declared to be Christian (80%). Fifty-nine percent of their mothers and 56% of their fathers had at least a high school education.

The local psychology department’s ethics committee approved this study and all procedures were performed in accordance with the Italian Association of Psychology (2015) ethical principles for psychological research. After obtaining written consent from school principals and teachers, university dean and faculties, participants and their parents (in the case of adolescents), a survey assessing different aspects of religiousness and well-being was administered collectively during class sessions under the supervision of one research assistant and one postgraduate student. The survey took no longer than 40 min to complete.

Measures

Socio-demographics

Respondents were asked to indicate their age, gender , religious affiliation , and their maternal and/or paternal level of school completed.

Religious Commitment

Religious commitment was assessed using the ten-item Religious Commitment Inventory (RCI-10; Worthington et al. 2003). The items (e.g., “My religious beliefs lie behind my whole approach to life”) capture commitment in terms of adherence to one’s religious values , beliefs , and practices . Items were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not all true of me) to 5 (totally true of me) and were averaged to create an overall score with higher scores indicating higher levels of religious commitment . The scale was translated from English into Italian following the recommendations of the International Test Commission (2005). Cronbach’s alphas varied between .91 and .95 across age groups.

Optimism

Optimism was assessed using the ten-item Italian version of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R; Giannini, Schuldberg, Di Fabio, & Gargaro, 2008; Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994). The items (e.g., “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”) capture positive expectations for future outcomes, except for the four filler items that were not scored. Items were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). After reversing the three negatively worded items, responses were averaged to create an overall score of optimism, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the construct . Cronbach’s alphas varied between .63 and .80 across the age groups.

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was assessed using the five-item Italian version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Goldwurm, Baruffi, & Colombo, 2004; Pavot & Diener, 1993). The items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”) capture the perception of one’s quality life. Items were rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) and were averaged to create an overall score of satisfaction with life, with higher scores indicating higher levels of the construct . Cronbach’s alphas varied between .83 and .87 across age groups.

Analytic Plan

A multiple group path analysis was performed using structural equation modeling with age group as grouping variable. All analyses controlled for age within each group and gender (with these two variable assumed as uncorrelated in the model). According to Faraci and Musso (2013), to evaluate model fit different indices were inspected (adopted cut-offs in parentheses): chi-square test with the associated p-value (p > .05), comparative fit index (CFI ≥.95), and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA ≤.06; RMSEA 90% CI ≤.10). Initially, an unconstrained model in which path coefficients were allowed to vary between the three age groups was tested. Next, a constrained model where all path coefficients were set equal across age groups was tested and compared with the unconstrained model using the chi-square difference (Δχ2), the difference in CFI values (ΔCFI) and the difference in RMSEA values (ΔRMSEA). If Δχ2 had been smaller than the chi-square critical value at the difference in degrees of freedom of the two tested models, ΔCFI >−.010 and ΔRMSEA <.015 (Chen, 2007), the more restrictive model would have been preferred; otherwise, the less restrictive model would have provided a better fit to the data. In the latter case, a partially constrained model would then have been tested.

Results

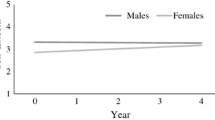

Descriptive statistics for the key study variables are summarized in Table 1. The initial unconstrained model had a good fit, χ2(3) = 1.66, p = .64; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 [90% C.I. = .000–.10]. The constrained version of the model had a significantly worse fit compared to the unconstrained model, Δχ2(6) = 16.15, p < .05, ΔCFI = −.040, ΔRMSEA = .080. Inspection of modification indices suggested releasing the constraint between religious commitment and optimism for late adolescents. The partially constrained model had excellent fit, Δχ2(5) = 6.33, p > .05, ΔCFI = .000, ΔRMSEA = .000. Standardized coefficients for this final model are shown in Fig. 2.

Multiple-group path model for the relationships between study variables, moderated by age group. Note : Maximum likelihood standardized coefficients are shown. Solid lines represent significant pathways , dashed lines represent nonsignificant relationships. Controlling variables (age within each group and gender ) are not presented for reasons of parsimony. *** p < .001

Within the middle adolescence and emerging adult groups, direct links showed that religious commitment was significantly connected with increases in optimism and satisfaction with life as well as optimism was significantly related with increases in satisfaction with life. Also, there was evidence of mediating positive role of optimism between religious commitment and satisfaction with life (respectively, β = .12, p < .001 and β = .13, p < .001). Within the late adolescence group, direct links showed that religious commitment and optimism were significantly connected with increases in satisfaction with life, but no significant relation emerged between religious commitment and optimism. As a consequence, no evidence of mediating role of optimism in the relationship between religiosity and life satisfaction was found (β = −.03, p > .05).

Discussion

The purpose of our chapter was to better elucidate the relative and combined contribution of religiosity and optimism in promoting adolescents and emerging adults’ well-being. Framed within the PYD perspective, the conceptual model we tested assumed that religiosity is linked to positive evaluation of life also through its role in directing one’s view of life events in a hopeful way, i.e., optimism. Our study was the first to test such a model in Italy , a cultural context in which religiosity (i.e., Catholicism ) is widespread and particularly salient for individuals’ life (Garelli, 2013). In addition, another novelty of our contribution consisted in investigating how religiosity , optimism, and satisfaction with life relate to one another in different phases of the life cycle.

In general, results are in line with our predictions. Direct paths from religiosity and optimism to life satisfaction were found in all age groups examined (middle adolescents, late adolescents, and emerging adults). Religiosity was directly and positively associated to optimism as well as indirectly and positively related to life satisfaction among middle adolescents and emerging adults, but not among late adolescents. These findings demonstrated that both adolescents and emerging adults with an increased religious commitment tend to have higher levels of life satisfaction, as suggested by previous works (Kim, Miles-Mason, Kim, & Esquivel, 2013; Abdel-Khalek, 2012). This kind of connection may also be mediated by the role of the optimistic views, but it seems to depend on the particular age characteristics during adolescence and emerging adulthood . In fact, a positive association between religious commitment and levels of optimism was found only among middle adolescents and emerging adults, whereas no significant relationship was found among late adolescents.

From a developmental standpoint, the presence of age-related differences in the association between religiosity , optimism, and life satisfaction may be explained by considering the changes in the ways of experiencing religiosity that occur during adolescence and emerging adulthood . Middle adolescents are more influenced by the religious beliefs and values of their parents and other social agencies (King, Furrow, & Roth, 2002). Also, their conception of religiosity is quite idealized because they are still not able to find their own manner to interpret religious contents due to their level of cognitive and identity development (Fowler & Dell, 2006). Thus, it might be that, in a context like Italy , where a collective dimension of religion is still salient (Garelli, 2007), youth who show high religious commitment rely on practices and communities of their faith to find purpose in life and support. Late adolescents, instead, develop a more critical thinking and stable sense of identity helping them to reflect on the culture they live in and on their religious beliefs (Chan et al., 2015; Zarrett & Eccles, 2006). Thus, they become more able to differentiate diverse domains of their lives, such as religion, family, school/work, and personal relationships. As a consequence, religiosity is not necessarily considered as a dimension that guarantees security and positive expectations for the future; rather it might be questioned and doubted (Chan et al., 2015). For this reason, late adolescents are likely to put their optimistic expectancies of the future in something different than religiosity , which may be identified in other personal and social resources (Ek, Remes, & Sovio, 2004). Finally, further cognitive and social advances make emerging adults more able to frame their lives through lens of a personal set of religious beliefs that they have matured independently of parents or of the influence of religious institutions (Arnett & Jensen, 2002). Therefore, during this period, religious commitment is experienced with higher awareness and its associations with optimism and positive expectations towards the future are positively reconsidered. This is especially valid in a cultural context like Italy, where religiosity represents a resource in times of struggle that enhances hope that things can get on the right side (Garelli, 2013).

In brief, religiosity seems to be an important positive correlate of well-being in terms of life satisfaction. This link can be both direct and indirect through the mediating role of optimism. However, the latter case depends on age specific developmental characteristics that adolescence and emerging adulthood undergo. Still, these processes are primarily relevant in cultural contexts in which the religious dimension is clearly salient, helping individuals hold religious beliefs , either inherited, or passively accepted or personally chosen.

Although our findings provide interesting insights into the associations between religiosity and well-being among Italian adolescents and emerging adults, they should be considered in light of some limitations. First, the data were cross-sectional and correlational , which hinders our ability to clearly establish the mediating processes. Thus, longitudinally research is needed to determine temporal ordering and causality . Second, the measures were all self-report and, as a consequence, they might lead to social desirability bias. Future studies should adopt mixed methods to provide additional information about the views of adolescents and emerging adults on religiosity and well-being, as well as experimental designs in order to further validate our results. Third, our sample was mostly composed of girls within both adolescent and emerging adult groups. As a consequence, although we inserted gender as a control variable in our model, it was not possible to reliably investigate gender differences in this study. However, as previously suggested, there exist differences in the ways boys and girls approach religiosity (King & Roeser, 2009; Chan et al., 2015), even though such discrepancies might be considered as culture-specific , rather than generalizable (Loewenthal, MacLeod, & Cinnirella, 2002). Also, gender has been found to be a moderator on the association between religiosity and well-being (Maselko & Kubzansky, 2006). Consequently, there is the need to specifically take into account the role of gender in examining the influence of religiosity on well-being. In addition, it would be useful to investigate potential differences emerging when adopting an approach that distinguishes between religious and non-religious people. In this sense, the main question would be whether those declaring to be non-believers would also show a significant relationship between optimism and life satisfaction and have a hopeful and optimistic attitude in life. Although prior works pointed out that optimism is linked to satisfaction with life independently of individuals’ religiosity (e.g., Mishra, 2013), next investigations should implement such facets to better elucidate the specific contribution of religiosity and optimism on youth’s and emerging adults’ good life conditions . Finally, our research mainly focused on an individual level of analysis while neglecting the impact of social resources , such as family or peers (Barry et al., 2010; King et al., 2002; King, 2003), on the associations between religiosity and adolescents’ and emerging adults’ well-being. Further studies should also investigate these issues.

Despite these limitations, our study makes a novel contribution to the literature at least in two aspects. First, it highlights that religiosity may be positively associated with youth psychological well-being, although some works show that it can be related to mental health problems such as depression (Cotton, Larkin, Hoopes, Cromer, & Rosenthal, 2005) and negative emotions such as feelings of guilt and alienation (Exline, Yali, & Sanderson, 2000). Second, it extends our understanding of how religion is related to the trajectories of psychological well-being among adolescents and emerging adults growing in contexts where religion is closely aligned with culture. In fact, while some other studies confirmed the mediation role of optimism in the relationship between religiosity , well-being and mental health among emerging adults (Salsman et al., 2005) and adults (Hirsch, Nsamenang, Chang, & Kaslow, 2014), to our knowledge this is the first to address such a topic including adolescents along with emerging adults.

In summary, the questions and the topics so far addressed shed light on the mechanisms by which religiosity may help adolescents and emerging adults enhance their positive expectations about future outcomes and promote their life satisfaction. In addition, the current research highlights that there are age-related changes in these mechanisms. In line with the PYD framework, such findings may be useful to design age-specific intervention considering religiosity as a significant resource promoting young people ’s successful growth . These interventions may result in an enhancement of optimistic and satisfactory life-styles in youth and in turn, in a potential strengthening of their contribution to self, family, and society as the PYD literature suggests (e.g., Lerner, Alberts, Anderson, & Dowling, 2006). In this sense, religiosity , optimism, and satisfaction with life are significant constructs that can positively contribute to the ecology of youth and emerging adults, in terms of both theoretical explanations and practical interventions .

References

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2012). Subjective well-being and religiosity: A cross-sectional study with adolescents, young, and middle-age adults. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 15, 39–52.

Arnett, J. J. (2014). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the Twenties (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J., & Jensen, L. A. (2002). A congregation of one: Individualized religious beliefs among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 17, 451–467.

Bader, C. D., Baker, J. O., & Molle, A. (2012). Countervailing forces: Religiosity and paranormal beliefs in Italy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51, 705–720.

Barry, C. M., & Abo-Zena, M. M. (2014). Emerging adults’ religious and spiritual development. In C. M. Barry & M. M. Abo-Zena (Eds.), Emerging adults’ religiousness and spirituality. Meaning-Making in an Age of Transition (pp. 21–38). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Barry, C. M., Nelson, L., Davarya, S., & Urry, S. (2010). Religiosity and spirituality during the transition to adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34, 311–324.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18, 293–299.

Chan, M., Tsai, K. M., & Fuligni, A. J. (2015). Changes in religiosity across the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1555–1566.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 464–504.

Cotton, S., Larkin, E., Hoopes, A., Cromer, B. A., & Rosenthal, S. L. (2005). The impact of spirituality on depressive symptoms and health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 529, 7–14.

Crocetti, E., Rabaglietti, E., & Sica, L. L. (2012). Personal identity in Italy. In S. J. Schwartz (Ed.), Identity around the world: New directions for child and adolescent development (pp. 87–102). New York, NY: Wiley.

Dahl, R. E. (2004). Adolescent brain development: A period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Keynote address. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1021, 1–22.

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Myers, D. G. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 1278–1290.

Doxa (2014). Indagine demoscopica sui temi della religiosità e dell’ateismo [Opinion poll on religiosity and atheism]. Retrieved from, http://www.doxa.it/news/religiosita-e-ateismo-in-italia-nel-2014/

Ek, E., Remes, J., & Sovio, U. (2004). Social and developmental predictors of optimism from infancy to early adulthood. Social Indicators Research, 69, 219–242.

Exline, J. J., Yali, A. M., & Sanderson, W. C. (2000). Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 1481–1496.

Faraci, P., & Musso, P. (2013). La valutazione dei modelli di equazioni strutturali [The evaluation of structural equation models]. In C. Barbaranelli & S. Ingoglia (Eds.), I modelli di equazioni strutturali: Temi e prospettive (pp. 111–150). Milano, Italy: LED.

Ferguson, S. J., & Goodwin, A. D. (2010). Optimism and well-being in older adults: The mediating role of social support and perceived control. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 71, 43–68.

Fowler, J. W., & Dell, M. L. (2006). Stages of faith from infancy through adolescence: Reflections on three decades of faith development theory. In E. C. Roehlkepartain, P. E. King, L. Wagener, & P. L. Benson (Eds.), The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence (pp. 34–45). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Furrow, J. L., King, P. E., & White, K. (2004). Religion and positive youth development: Identity, meaning, and prosocial concerns. Applied Developmental Science, 8, 17–26.

Garelli, F. (2007). Research note between religion and spirituality: New perspectives in the Italian religious landscape. Review of Religious Research, 48, 318–326.

Garelli, F. (2013). Flexible catholicism, religion, and the church: The Italian case. Religions, 4, 1–13.

Giannini, M., Schuldberg, D., Di Fabio, A., & Gargaro, D. (2008). Misurare l’ottimismo: proprietà psicometriche della versione italiana del Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) [Measuring optimism: psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R)]. Counseling, 1, 73–83.

Goldwurm, G. F., Baruffi, M., & Colombo, F. (2004). Qualità della Vita e Benessere Psicologico. Aspetti comportamentali e cognitivi del vivere felice [Quality of life and psychological well-being. Behavioral and cognitive aspects of happy life]. Milano, Italy: McGraw-Hill.

Graham, C., & Crown, S. (2014). Religion and well-being around the world: Social purpose, social time, or social insurance? International Journal of Wellbeing, 4, 1–27.

Hardy, S. A., Walker, L. J., Rackham, D. D., & Olsen, J. A. (2012). Religiosity and adolescent empathy and aggression: The mediating role of moral identity. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 4, 237–248.

Hayward, R. D., & Krause, N. (2014). Religion, mental health, and well-being: Social aspects. In V. Saroglou (Ed.), Religion, personality, and social behavior (pp. 255–280). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Hill, P. C., Pargament, K. I., Hood, R. W., Jr., McCullough, M. E., Swyers, J. P., Larson, D. B., et al. (2000). Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30, 51–77.

Hirsch, J. K., Nsamenang, S. A., Chang, E. C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2014). Spiritual well-being and depressive symptoms in female African American suicide attempters: Mediating effect of optimism and pessimism. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6, 276–283.

Ho, M. Y., Cheung, F. M., & Cheung, S. F. (2010). The role of meaning in life and optimism in promoting well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 658–663.

International Test Commission. (2005). International Test Commission guidelines for translating and adapting tests. Retrieved from, https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation.pdf

Italian Association of Psychology. (2015). Codice etico per la ricerca in psicologia [Ethical code for psychological research]. Retrieved from, http://aipass.org/node/11560

Jankowski, P. J., Hardy, S. A., Zamboanga, B. L., & Ham, L. S. (2013). Religiousness and hazardous alcohol use: A conditional indirect effects model. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 747–758.

Johnson, B. R., Jang, S. J., Larson, D. B., & Li, S. D. (2001). Does adolescent religious commitment matter: A re-examination of the effects of religiosity on delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 38, 22–43.

Karaś, D., Cieciuch, J., Negru, O., & Crocetti, E. (2015). Relationships between identity and well-being in Italian, Polish, and Romanian emerging adults. Social Indicators Research, 121, 727–743.

Kelley, B. S., & Miller, L. (2007). Life satisfaction and spirituality in adolescents. Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion, 18, 233–262.

Kim, S., Miles-Mason, E., Kim, C. Y., & Esquivel, G. B. (2013). Religiosity/spirituality and life satisfaction in Korean American adolescents. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5, 33–40.

King, P. E. (2003). Religion and identity: The role of ideological, social and spiritual contexts. Applied Developmental Science, 7, 197–204.

King, P. E., & Boyatzis, C. (2015). Religious and spiritual development. In M. E. Lamb & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Socioemotional processes (7th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 975-1021). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

King, P. E., & Roeser, R. W. (2009). Religion and spirituality in adolescent development. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Individual bases of adolescent development (Vol. 1, 3rd ed., pp. 435–478). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

King, P. E., Furrow, J. L., & Roth, N. (2002). The influence of family and peers on adolescent religiousness. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 21, 109–120.

Kirk, C. M., & Lewis, R. K. (2013). The impact of religious behaviors on the health and well-being of emerging adults. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16, 1030–1043.

Krause, N. (2002). Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57B, 332–347.

Laudadio, A., & D’Alessio, M. (2010). Il percorso di validazione della Religious Attitude Scale (RAS) [The validation process of the Religious Attitude Scale (RAS)]. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, 37, 465–486.

Lerner, R. M., Alberts, E. A., Anderson, P. M., & Dowling, E. M. (2006). On making humans human: spirituality and the promotion of positive youth development. In E. C. Roehlkepartain, P. E. King, L. Wagener, & P. L. Benson (Eds.), The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence (pp. 60–72). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., von Eye, A., Bowers, E. P., & Bizan-Lewin, S. (2011). Individual and contextual bases of thriving in adolescence: A view of the issues. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 1107–1114.

Loewenthal, K. M., MacLeod, A. K., & Cinnirella, M. (2002). Are women more religious than men? Gender differences in religious activity among different religious groups in the UK. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 133–139.

Magyar-Russel, G., Deal, P. J., & Brown, I. T. (2014). Potential benefits and detriments or religiousness and spirituality to emerging adults. In C. M. Barry & M. M. Abo-Zena (Eds.), Emerging adults’ religiousness and spirituality. Meaning-making in an age of transition (pp. 39–55). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Maselko, J., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2006). Gender differences in religious practices, spiritual experiences and health: Results from the US General Social Survey. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 2848–2860.

Mishra, K. K. (2013). Optimism and well-being. Social Science International, 29, 75–87.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172.

Pearce, M. J., Little, T. D., & Perez, J. E. (2003). Religiousness and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 267–276.

Sabatier, C., Mayer, B., Friedlmeier, M., Lubiewska, K., & Trommsdorff, G. (2011). Religiosity, family orientation, and life satisfaction of adolescents in four countries. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 1375–1393.

Salas-Wright, C. P., Vaughn, M. G., & Maynard, B. R. (2014). Religiosity and violence among adolescents in the United States: Findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2006–2010. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 1178–1200.

Salsman, J. M., Brown, T. L., Brechting, E. H., & Carlson, C. R. (2005). The link between religion and spirituality and psychological adjustment: The mediating role of optimism and social support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 522–535.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078.

Steger, M. F., & Frazier, P. (2005). Meaning in life: One link in the chain from religiousness to well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 574–582.

Steinberg, L. (1999). Adolescence (5th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Van Cappellen, P., Toth-Gauthier, M., Saroglou, V., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2016). Religion and well-being: The mediating role of positive emotions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17, 485–505.

Worthington, E. L., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., et al. (2003). The Religious Commitment Inventory – 10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 84–96.

Yonker, J. E., Schnabelrauch, A., & DeHaan, L. G. (2012). The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 299–314.

Zarrett, N., & Eccles, J. (2006). The passage to adulthood: Challenges of late adolescents. New Directions for Youth Development, 111, 13–28.

Zeb, R., Riaz, M. N., & Jahangir, F. (2015). Religiosity and optimism as predictors of psychopathology and mental health. Journal of Asian Development Studies, 4, 67–75.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Inguglia, C., Musso, P., Iannello, N.M., Lo Coco, A. (2017). The Contribution of Religiosity and Optimism on Well-Being of Youth and Emerging Adults in Italy. In: Dimitrova, R. (eds) Well-Being of Youth and Emerging Adults across Cultures . Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology, vol 12. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68363-8_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68363-8_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-68362-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-68363-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)