Abstract

Despite attempts to find appropriate regulatory solutions, the issue of the civil liability of statutory auditors and the perceived need for some form of liability limitation continues to evoke divergent views and reactions. The analysis in this chapter indicates that such divergence is characteristic not just of the positions taken by various stakeholder groups but also of the differences in the nature and scope of auditor liability regimes adopted in individual countries. This chapter uses such analysis to suggest that the auditor liability debate and the continuing search for a regulatory solution has potentially hindered more focused consideration of the professional identity of auditors, their capacity to meet public expectations and the extent to which such capacity (and achievements) varies across countries and the differing cultural contexts in which auditors work.

This Chapter includes the paper originally titled “Re-Thinking Auditor Liability: the case of the European Union’s Regulatory Reform” and discussed at the Fifth International Workshop on Accounting and Regulation in 2010.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

6.1 Introduction

“The problem confronting the profession today is to see to it that the liability is ‘clearly defined’, and that the extent of damages bears some reasonable relationship to the gravity of the accountant’s offense” (Carey 1965, p. 415). “If audit is to be reformed to help to prevent another global financial crisis, there needs to be a real debate on the issue of auditor liability” (Davies, ACCA’s Technical Head 2012).Footnote 1

The above statements made nearly half a century apart lead to the intriguing observation that, despite many years of debate and a number of regulatory attempts to develop public policy solutions, the issue of the civil liability of statutory auditors still continues to be one of the most concerning for the accountancy profession. The profession has for many years pointed to the rise in litigation against auditors by both their clients and third parties that rely on the audit opinion for decision making (Talley 2006). Critics of the profession often represent such activity as a signal of the public’s distrust in the ability of auditors to perform their duties properly, a perception that was significantly reinforced by notable corporate collapses such as Enron in 2001 and Lehmans in 2008 (Sikka 2008; Quick et al. 2008). The profession, however, routinely emphasises the inequitable, punitive and untenable nature of such a legal position, pointing to ‘an epidemic of litigation’ (Arthur Andersen & Co. et al. 1992, p. 1), an ‘outrageous level of current claims’ (ICAA 1995, p.11), and the possibility that ‘many audit firms face the risk of Armageddon’ (Ward 1999, p. 388).

Some record claims brought against auditors in recent years, such as the £2bn negligence claim made by the British insurer Equitable Life against Ernst and Young and the $1 bn lawsuit against KPMG for their audit of the failed US subprime lender New Century FinancialFootnote 2 have been used by the profession to lend further momentum to the above arguments, with the Big 4 audit firms regularly stressing that the consequences of any such litigation threatened the audit profession’s survival. Or as Martyn Jones, the UK’s national audit technical partner for Deloitte, concluded ‘Armageddon still exists’, pointing, in the process, to the damaging effects of actual and potential litigation ‘on partners, potential partners and people thinking of joining the firm, when the firm is not freely able to contract’ Footnote 3.

Such comments or responses on the part of the profession have been underpinned by its desire to see (or promote the case for) reform of auditors’ ‘joint-and-several’ liabilityFootnote 4, replacing it with alternative, more constrained liability arrangements, such as capped or proportionate liabilityFootnote 5. The profession, and particularly its leading firms, have committed to active processes of political engagement in the pursuit of reform, both at national and international levels (e.g. see Roberts et al. 2003; Humphrey and Samsonova 2012). The success of such efforts, however, is open to question. In the UK, for instance, long-running campaigns on the part of the profession for auditor liability limitation have for many years emphasised the catastrophic consequences of non-action both for the country’s auditing community and the public at large (see Accountancy Age 1993, 1994a, 1994b; Accountant 2003; Sunday Times 2004). Revisions to the Companies Act were secured in 2006, but they did not specify any limitation of liability in tort law and instead stipulated that the appropriateness and terms of any such limitation should be the subject of a contractual agreement between the auditor and the company’s shareholders. In the US, the Big 4 firms’ responses in 2008 to the draft report by the US Treasury’s Advisory Committee on the Auditing provided another illustration of their desire to convince the government of the case for auditor liability limitation (see Centre for Audit Quality 2008a; Ernst and Young 2008; Grant Thornton 2008; Centre for Audit Quality 2008b). However, the final draft of the Treasury’s Advisory Committee’s report failed to list auditor liability as an area recommended for reform.

It is evident that there are countries that have chosen to adopt some form of statutory auditor liability limitation (e.g. Australia, Austria, Belgium, Germany, Greece and Slovenia) and that some of these choices can be seen to be as a consequence of lobbying campaigns by the profession as well as a combination of associated contextual factors. In Australia, for example, a series of reforms of auditor liability led to the introduction in 2004 of proportionate liability, replacing the previous principle of joint and several liabilities. Furthermore, some individual states in the country (such as New South Wales) have since introduced a liability cap in addition to the proportionate liability regime required by law and in combination with compulsory indemnity insurance. Apart from a considerable support for limited liability expressed by Australian auditors, the above changes were also said to be driven by the fact that the insurance market for professional services was considered deeply dysfunctional and, therefore, a liability reform was thought to be necessary as a way to bring the level of available insurance in line with the level of audit supplyFootnote 6.

Furthermore, individual country examples continue to be used as grounds for action in other countries. In its recent report ‘Audit reform: aligning risk with responsibility’, for example, the UK’s association of chartered certified accountants (ACCA) pointed to the experiences of Australia and other countries that introduced limited liability arrangements in tort law as a way to make a point that ‘the argument for reforming the liability rules has been widely accepted’ (ACCA 2011, p. 8). Nevertheless, the profession’s efforts to secure liability reform at the international level have certainly not delivered the desired harmonised, ‘one-size-fits-all’ auditor liability regime. For instance, the much anticipated Recommendation issued in the European Union (European commission 2008), while encouraging the European Member States to introduce a form of limited liability for auditors, did not impose on them any definitive obligation to do so. Further, the European Commission’s more recent Green Paper on auditing did not even make any mention of the subject as a live topic of regulatory reform (for more discussion, see Humphrey and Samsonova 2012).

In this chapter, we consider the underlying causes of what is an uneasy status quo, with audit liability limitation being a subject that has, at different times, attracted considerable momentum, engagement and frustration on the part of the profession, regulators and stakeholders. Such analysis strongly suggests that a broad-based, long-standing international consensus on auditor liability limitation reform is, for varying reasons, unlikely to materialise. Further, we argue that allowing auditor liability debate to be dominated by the search for such a regulatory solution is serving to detract from more serious consideration of the auditor’s professional identity and his/her capacity to meet public expectations, particular to the differing countries in which they work.

The remainder of the chapter is structured as follows. The following section will problematise the issue of auditor liability, reviewing the competing set of arguments for and against reform. Section 6.3 and 6.4 of the chapter demonstrate the challenges that liability reformers face, first, by presenting evidence of residing differences in national regimes of auditors’ civil liability and, second, by reviewing recent attempts at harmonising the rules for auditor liability across EU Member States. The closing section reflects on such regime differences and attempts to secure auditor liability reform, both within and across countries, arguing that underpinning debates and reform agendas is a more fundamental problem of professional identity and a pressing need to know more about the world of auditing.

6.2 Competing Perspectives on Auditor Liability Limitation

The subject of auditor liability and the need for its limitation has been associated with a diversity of, often conflicting, attitudes and views expressed by the regulatory community, users of audit reports and the audit profession. Over the years, it has evolved into one of the most controversial aspects of auditing, dividing stakeholder opinions into those that see the ‘joint and several’ (i.e. unlimited) liability regimes adopted in many countries as necessary and appropriate to the important role that auditors play in a society and those that claim such regimes are too onerous and require some form of limitation.

Arguments in favour of limiting liability have been based on the premise that as businesses (their stakeholders and their accounting systems) have become numerous, larger and more complex, the risk and economic consequences of audit failure have risen significantly, and left auditors ‘unduly exposed’ to litigation, with a growing number and scale of legal claims against them. O’Malley (1993, p. 7) saw a clear cause and effect relationship in the sense that ‘any effort on the profession’s part to meet these (rising) public expectations always seems to generate newer and even more unrealistic expectations that will almost certainly produce increased litigation’. The rise of litigation against the profession from the 1960 s onwards in countries such as the US, appears to have due to a mix of factors, including legislative changes, numerous corporate collapses in the economic downturn of the late 1960s and early 1970s and the growing commercial success of the profession (which was suspected as helping to portray them as attractive litigation targets)—coupled with a concern that such commercialisation (especially in terms of the pursuit of revenue growth through a rise in consulting activities) was undermining the profession’s commitment to auditor independence and the quality of audit work. A more active and interventionist regulatory stance by the SEC was also seen as playing a key factor, with the 1966 criminal action brought against Lybrand, Ross Brothers and Montgomery for its audits of Continental Vending MachinesFootnote 7, a New York City-based maker of vending equipment, according to Brewster (2003), not only being a ‘shock to Lybrand, and to the rest of the profession, for that matter’ (p. 118), on a scale comparable to that of the Enron debacle, but a case that ‘opened the litigation floodgates’ (p. 146). Brewster goes on to note, for example, that, before 1969, Price Waterhouse had seen only three cases of audit-related litigation in its history, whereas by the early 1970s, the number of such cases had jumped to 40–50. By 1990, the US government had filed over a dozen lawsuits with claims in access of $2 bn. At another level, one could witness some significant developments in law establishing auditors’ duties in relation to third parties that, particularly in the 1970s widened the range of parties that could claim damages against auditors) (Lys 2005; Baker and Prentice 2007, 2008), together with a continuing series of corporate scandals around the world (which included, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, cases such as Barings, BCCI, Maxwell/Mirror Group, Polly Peck, Praise the Lord (PTL) Industries and the multiple Savings and Loan collapse in the US) that significantly undermined public trust in auditors’ ability to do their job properly. By the late 1990s, it was being reported that total damages claimed against auditors each year in the UK alone were well in excess of £1 billion (Ward 1999), while others asserted that litigation had become the most significant contributor to the growing cost of an audit and represented perhaps the biggest threat to the audit profession (Siliciano 1997).

Furthermore, there has been emerging empirical evidence suggesting that a growing number of legal cases against auditors have had a significant effect on the auditors’ ability to perform their duties properly, and particularly, on the quality of audit judgement (Koch and Schunk 2009). Specifically, some senior audit professionals claimed that auditors increasingly adopt a more apprehensive approach to taking a ‘professional stands’ as a consequence of an increased litigation risk; and that this situation can impair the overall quality of financial reporting (O’Malley 1993). Accordingly, limiting auditor liability has been presented as a way to tackle the problem of defensive behaviours that auditors develop as a way to shield themselves from the possibility of litigation. Also, it has been argued that strict liability regimes can force experienced auditors to abandon the profession or make newly qualified professionals reluctant to enter, which has a longer term, detrimental effect on overall standards of audit quality (Hill Metzger and Wermert 1994).

Some, albeit again within the profession, have gone so far as to suggest that unlimited liability may negatively influence the economy as a whole. The roots of this argument rest in the multifaceted nature of the role served by the auditor and the capacity of a liability regime to upset the delicate balance associated with such a function. To some extent, the risk of litigation is linked to the very nature of auditing where auditors’ owe a duty of care to the company’s owners (and by association, to third parties reasonably expected to rely on the audit report in their decision making); however, it is the management that auditors are in contact with during an audit. In essence, auditing involves balancing off often conflicting interests and objectives of different economic agents, with an understanding that any one failure to do so may lead to a legal claim. Furthermore, investors of a troubled company often turn to its auditor for compensation, regardless of the nature or degree of the auditor’s involvement, as the company itself is often insolvent. This phenomenon, referred to as the “deep pockets” syndrome (Palmrose 1997) has been said to be further exacerbated by the fact that auditors have been required to hold professional indemnity insurance, which de-facto, reinforces a perception of auditors as underwriters possessing sufficient funds to compensate for losses incurred. In conditions of unlimited liability, auditors’ capacity to mitigate litigation risk, especially to third parties, has been held to centre on their power to choose their audit clients—and, in consequence, to exhibit a greater reluctance to take on any clients that they perceive as overly risky. A company which cannot attract the services of an audit firm with the highest reputation may find, subsequently, that its financial accounts are not regarded to have the same, or a satisfactory, level of credibility and trustworthiness, making it more difficult for them to secure external funding (in the form of equity investment or bank lending), with, ultimately, adverse consequences for the country’s general economic development (Ward 1999).

Despite this range of argument and rationalisation in favour of limiting auditors’ civil liability, there has been strong opposition to any such moves. Among other things, the opponents of limiting liability have argued that any form of limitation would damage innocent plaintiffs by significantly reducing the likelihood of them recovering the damages suffered and effectively shielding auditors who failed to meet their professional duties. As such, it is argued that a system of ‘joint and several’ liability encourages fair treatment of vulnerable third parties while maintaining social justice (O’Malley 1993). It has been also regularly pointed out that audit firms have failed to provide real evidence of the true impact economic impact of litigation against auditors (as most cases are settled outside court)—and that the amount of compensation awarded by the courts is not as overwhelming as auditors have claimed (Gwilliam 2006) and that final settlements are often significantly lower than the initial damages claimed (Cousins et al. 1999). In this regard, the argument put forward by the proponents of unlimited liability has been that the problem of ‘catastrophic litigation’ has been created by a profession that has increasingly put commercial priorities above social obligation. From this perspective, the calls for liability limitation are seen as camouflaging or not giving due respect to the commercial success of the largest accounting firms and diverting the public’s attention from fundamental issues, such as ruling standards of audit quality and effectively leaving society to deal with the consequences of audit failure (Sikka 2008). It has also been argued that the obligation on a profession claiming to serve the public interest requires it to be vigilant in exercising its professional judgement, and not seeking legalistic solutions more compatible with the role of and societal expectations held out for technicians (see Merino and Kenny 1994).

The profession’s response has been that cases like Enron have provided categorical proof of the cataclysmic consequences of audit failure and the demonstrably inequitable nature of an unlimited liability regime that can bring a whole audit firm down on the basis of one audit failureFootnote 8. Such arguments are, in turn, countered by critics who have argued that the problems at Arthur Andersen, Enron’s auditor, were more systemic in nature and that the fate of Andersen was sealed, not by the peculiarities of the liability regime, but by the damage that the Enron case had done to its reputation, integrity and capacity to provide high quality audits.

A further line of argument has been to use the deterrent effect that auditors utilise themselves as an indication of the inherently intangible benefits of the audit. Just as auditors emphasise that the true benefit of the audit depends not just on what auditors detect through their work but also what their presence deters and prevents, advocates of a strict liability regime have emphasised its importance in ensuring that auditors deliver in terms of their public accountability, especially their duty of care to third parties that rely on their opinion. Here, it is argued that any limitation of liability would adversely affect auditors’ incentives to perform their duties properly, and as a result, further undermine public confidence in the reliability of financial reporting (Gietzmann et al. 1997). From this perspective, the risk or ‘threat’ of litigation has been seen as a vital means for guiding auditors’ behaviours, or, rather, providing a deterrent effect, constraining auditors’ freedom of action in a context where the quality of audit work is inherently difficult to observe. In this sense, a distinction has been made between the self-interest of the audit profession in promoting limited liability and the public’s desire for auditors to commit fully to the fulfilment of their social duties (Cousins et al. 1999).The counter-argument put forward by the auditing profession has continued to be that a punitive liability regime encourages defensive as against creative and insightful auditing, with auditors spending more time protecting their own position, obeying the rule but not the spirit of accounting and auditing regulations and ultimately performing audits which less serve the public interest. The aforementioned 2011 report by the ACCA illustrates that this argument has not lost favour in the profession, when stating that litigation ‘leads to so-called defensive auditing, accusations of ‘boiler plate’ opinions and a reputation for the profession as being excessively cautious and conservative’ (ACCA 2011, p. 6).

6.3 A Diversity of National Regimes of Auditor Liability

The degree and intensity of competing perspectives on auditor liability limitation is bolstered, if not fuelled, by the level of diversity in national auditor liability regimes. The examples provided in this section are illustrative of the diversity of national legislative approaches to the civil liability of statutory auditors. One source of variation relates to the scope of auditors’ liability exposure and the principle of joint and several liability, which means that any audit partner accused of wrongdoing can be required to pay the entire amount of damages irrespective of whether the damages were caused by an unprofessional audit or by the wrongdoing of other parties, such as the company’s management. Common ways of limiting liability exposure include setting a cap on the amount of damages claimed against auditors or applying the principle of proportionality where the damages are awarded in proportion to the auditor’s degree of wrongdoing. As far as auditor liability to third parties is concerned, despite the significant expansion of global capital markets and the scale and diversification of corporate activity, together with the importance of financial reports as a source of information about corporate performance, there is generally quite an adherence to restricting auditor liability primarily to claims by contractual parties.

The United States of America is a country where the issue of auditor liability has long been recognised as an area of concern. Amendments to Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure adopted in 1966 triggered a subsequent growth in the number of securities class actions (Mahoney 2009) and a sharp rise in litigation against auditors that was duly characterised as a ‘litigation explosion’ (Minow 1984). A further increase in the number of lawsuits filed against auditors in the wake of the ‘Savings & Loan crisis’ (involving a collapse of nearly a quarter of all American savings and loan associations during the late 1980s and early 1990s (Knapp 2011) stimulated a full-scale lobbying campaign, led by the then Big 6 largest audit firms and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AIPCA), to reform US securities laws. These efforts resulted in the passing of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) in 1995, making the US the first country to introduce a principle of proportionality—such that auditors’ liability had to be determined in proportion to their actual degree of culpability (see Roberts et al. (2003) for a detailed analysis). This contrasted to the previous position, which advocated the principle of joint and several liability—although the latter continues to be applied in cases where auditors have intentionally breached securities’ laws or for certain claims by small investors (e.g., where the investor’s net worth is at least $200,000 and the claim made against the auditor represents 10 % or more of this net worth). However, those criticising the 1995 Act pointed out that it made the audit firms exempt from being sued in a private, class action, which effectively meant that the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) became the only body that could instigate litigation against the firms (p. 186), although its capacity for action also appeared to have been limited by the 1994 Supreme Court decision in Central Bank of Denver N.A. versus First Interstate Banks of Denver. This eliminated the ‘aiding and abetting a securities law violation’ that had been a prime weapon that plaintiffs had used in arguing their case against the audit firms, which arguably made it more difficult for the SEC to sanction the auditors subsequently (Brewster 2003).

Interestingly, while the US auditor liability regime reflects the specific nature of the country’s accountancy culture, some similarities have been drawn to the French system, which also emphasises the role of an auditor in safeguarding the economic interests of a society as a whole, as opposed to just company owners. In this regard, the French Companies Act of 1966 (‘Loisur les Societes Commercials no. 66–537’) states that auditors owe a duty of care to the client company, individual shareholders and various third parties, providing that the plaintiff can prove the causal link between the fault of the auditors and the damages claimed. The same law also outlines the principle of proportionality which, like in the US, governs the treatment of the auditors’ liability exposure (Chung et al. 2010). Giudici (2010) reports a perception that a US auditor is ‘serving multiple principles: the company, the investors, the general public’ because the country’s securities laws do not specifically require that an auditor be appointed by the client company’s shareholders and hence auditors’ duty of care is not restricted to the shareholders onlyFootnote 9.

The treatment of auditors’ responsibility towards third parties has been significantly influenced by, or reflected in, case law development. In 1931, the highest court of New York in the seminal Ultramares Corp. versus Touche case considered whether an auditor was liable also to unknown third parties falling outside the auditor-client contract. The court ruling in this case, which was widely applied subsequently, effectively introduced a near-privity standard (although it did reject the specific claim made by the ‘third party’ against the auditor in the case). In subsequent years, the scope of third-party liability extended with the introduction of the ‘restatement rule’ which was first applied in 1968 in the Rusch Factors versus Levin case and was later embodied in Sect. 552 of the Restatement (Second) of Torts (1976) imposing third-party liability on professionals who supply inaccurate information to their client which is also relied on by non-clients, such as creditors, investors, and others stakeholder groups (Scherl 1994; Al-Shawaf 2012). The main difference between the near-privity and restatement principles is that the latter ‘does not require that the identity of specific third parties be known to the auditor, only that they be members of a limited group known to the auditor’ (Chung et al. 2010, p. 67). Also, some jurisdictions began to apply a ‘reasonable foreseeability’ rule, first established in the ruling of the New Jersey Supreme Court in Rosenblum vs. Adler (1983). This rule stipulated that an auditor is liable to all parties that he or she can reasonably foresee as potential users of an audit report. It is also worth noting in this regard the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) 2002 subsequently introduced a definition of a third party that included not just users of financial statements but also users of any non-financial reports that help to decide whether or not one can rely on the audit of such statements, including those produced by the audit firms themselves (e.g. firms’ registration documents) or regulators (e.g. PCAOB inspection reports).

Claims of the significant negative effects of litigation have been behind the recent attempts by the auditing profession in the US to push for amendments to statutory law in order to cap auditor liability exposure. For example, the Centre for Audit Quality, an organisation set up by the AICPA with membership of over 800 audit firms, heavily criticised the proposals by the US Treasury’s Advisory Committee on the Auditing Profession for reforming the US audit market because the proposals failed to respond to the Centre’s previous urging to address the ‘catastrophic litigation’ that the Centre felt was in danger of ‘destroying the profession’ (see Center for Audit Quality 2008a, 2008b). To substantiate their claims, auditors submitted key statistics showing that claims against the six largest US audit firms amounted to ‘an astounding $140 billion(Oberly 2008, p. 6). Despite significant support for such arguments from some of the country’s regulatory institutions (including the Committee on Capital Markets Regulation and the United States Chamber of Commerce), the final version of the Treasury’s report did not mention liability as an area recommended for reform.

In the UK, the decision by the British House of Lords in the Caparo case of 1990 substantially reshaped the treatment of auditor liability by British courts by promoting a more narrowly specified set of conditions under which auditors were considered to owe a duty of care (Napier 1998). According to the Caparo judgement, in the absence of extraordinary circumstances, auditors owed a duty of care to the client company only, and specifically, the company’s owners as a collective body. Hence, any third-party claims against auditors could be satisfied only if specific criteria were met (De Poorter 2008)—although subsequent years did see some expansion of privity by the British courts, fuelled by the increasing public pressure for the liability regime to account for the needs of a variety of financial statement users, such as individual shareholders, directors and various third parties (Gwilliam 2004; Pacini et al. 2000).

Like their counterparts in the US, British audit firms have taken an active role in their engagement with the country’s accounting professional and regulatory circles in their advocacy of limited liability. Sikka (2008), for example, shows how intense lobbying activities carefully orchestrated by the UK’s largest audit firms led to the passage of theLimited Liability Partnerships Act of 2000. This allowed UK audit firms to do what their North American counterparts had done for some time which is to form Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs), in addition to the existing right (established in the 1989 Companies Act) to incorporate as companies. Unlike ordinary partnerships, LLPs have a separate legal personality and so, in the event of litigation, the claimed amount of damages is first recovered from the audit firm’s assets and a partner is only liable for his own wrongdoing and not for the wrongdoing of his/her co-partners. In 2001, Ernst and Young was the first Big audit firm to register as a LLP with the intent that it would offer a greater protection to its individual partners and their personal assets. However, neither incorporation nor LLPs offer total liability protection and the so-called ‘catastrophic’ claim which may result in the failure of an individual audit firm is still a risk for any such incorporated firm or LLP.

A significant recent development was the revised Companies Act 2006 which allowed auditors to stipulate a contractual liability limitation in their engagement letter for any negligence, breach of duty, or breach of trust on the part of the auditor in relation to the audit (see Turley 2008). Any such limitation, however, has to be on an annual basis and be approved by a shareholder resolution. The liability limitation agreement (LLA) also had to be ‘fair and reasonable’, allowing the courts to override/amend any such agreement if it considered the agreement not to be so. Interestingly, the 2006 Companies Act also introduced additional arrangements to strengthen the emphasis on auditors’ accountability to users, which were widely seen as counterbalancing provisions for liability limitation. Among such arrangements was a new criminal offence, punishable by an unlimited fine, for auditors who ‘knowingly or recklessly’ provide a false audit opinion.

Since LLA were first permitted, their use has been impeded by a number of factors. Roach (2010), in this regard, points to the vague nature of LLAs which makes their application problematic. He further notes that the guidance issued by the UK’s Financial Reporting Council (FRC 2008), while providing some important clarifications, still left some questions unanswered, such as the subsequent responsibility of a company director whose recommendation of the adoption of an LLAs is followed by an action in which the company’s auditor is found to be negligent? Roach reported a generally unfavourable reaction to LLAs by the users of audit reports, such as institutional investors and that the whole viability of LLAs was significantly threatened by the SEC’s rejection of such a contractual liability limitation on the grounds that they represented a major breach of auditor’s independence (a move which saw the SEC seek to prevent UK audit firms with US-listed clients from entering into any LLA)Footnote 10. Such a stance by the SEC is not only suggestive of substantial differences in views of the most appropriate liability arrangements and the required scope of the auditor’s duty of care adopted in the two countries, but demonstrates that the issue of auditor liability limitation should not be viewed in (national) isolation. The SEC’s reaction also presents a significant hindrance to the operations of the audit firms themselves as a large number of FTSE 100 companies (which form the firms’ primary client base) also have their stock traded in New York and, therefore, find themselves having to follow the SEC requirements.

Such national variation in liability regimes, when coupled with the global nature of audit firms’ operations, means that the firms’ liability exposure is not constant and always subject to alteration and modification as a result of different jurisdictional action. Interestingly, the audit profession’s success in securing liability limitation is quite varied, with significant concessions being granted in countries that had already established quite strict liability arrangements. For instance, in Canada, auditors are required to compensate for damages incurred by the plaintiff if the latter is able to prove that the harm suffered can be directly attributed to the actions of the auditors. The 1997 Hercules versus Ernst & Young case reinforced this position by concluding that company investors have no right to sue the auditor in cases where financial statements are found to contain misstatements on the ground that auditors owe a duty of care primarily to the contractual party (Puri and Ben-Ishai 2003; Chung et al. 2010). Canadian auditors, like their British and American colleagues, can also form LLPs, while amendments to the Canada Business Corporations Act (CBCA) in 2001 saw joint and several liability being replaced with capped proportionate liability arrangements—with the audit profession being noted as the major driving force behind the reform (Puri and Ben-Ishai 2003). Under such arrangements, the scope of damages that the auditor can be held liable for is to be in proportion to the degree of his/her wrongdoing, although the auditor can still be required to cover up to a maximum of 50 % of the amount of damages awarded by the court against another defendant (such as company management) when the latter is insolvent. Such provisions only apply to cases of violation of the CBCA and not, for example, to violations of securities law.

The cap on auditor liability claims introduced in Germany has, over the years, been increased, a move, ironically, advocated by German auditors themselves in the hope of warding off any possible government measures seeking to increase the rights of third parties (Gietzmann and Quick 1998). The current legal provisions in Germany limit auditors’ contractual liability to €1 mn per audit and €4 mn for the audit of listed companies. Such a monetary cap, however, refers only to claims by the client, unlike countries like Belgium, Austria and Greece where the cap also covers liability to third parties (Gietzmann and Quick 1998; Kohler et al. 2008).

In environments with a relatively high level of litigious activities against auditors, laws stipulating auditor liability, while varied, can be expected to be relatively well developed and detailed in terms of both stipulating the scope of auditors’ liability exposure as well as the range of parties that can claim damages against auditors. In contrast, auditor liability rules in less litigious environments are often characterised by laws and regulation which are more general in their provisions. In Belgium, for example, where despite a few high-profile cases, litigation against auditors is comparatively low, national law has not introduced any specific requirements for auditor’s liability to third parties. Effectively this means that, since the 1970s when the national legislator mandated the publication of company financial reports, auditors have been considered liable to any party that relies on such reports as a source of information. And so, Belgian auditors are believed to owe a duty of care not just to the company shareholders but a wide range of other stakeholders, such as company employees, creditors and other groups, which underscores the significant emphasis that the country places on auditors’ social roles (De Poorter 2008). Belgium did recently introduce an absolute cap on liability, but as Roach (2010) notes, such a cap ‘was not based upon realisation that the principle of joint and several liability coupled with the deep pockets syndrome is inherently unfair’, as in the UK, but was ‘to improve the level of domestic insurance cover’ available to auditors’ (Roach 2010, p. 11).

There are also national environments where the issue of auditor liability limitation has clearly been assigned less social importance and significance. One example is Russia where ‘Western’-style auditing was introduced more than two decades ago but, at the time of writing, there are still no laws or regulations of a business or audit-specific nature that explicitly define auditors’ civil liability. Instead, such liability is determined with reference to the provisions of the Civil Code, article 15 of which states that ‘a person whose rights have been violated can demand full compensation for the damages incurred, unless laws and regulations exist that impose restrictions on the amount of compensation’. Furthermore, the focus in the Code is on the economic consequences of a contractual relationship where ‘individuals and companies are free to determine their respective rights and responsibilities as part of an agreement between them as long as such an agreement is not in contradiction with the existing legislation’ (article 1). This means that the Russian statutes contain no legislative provisions that stipulate an auditor’s liability to third parties. Samsonova (2012), for example, notes in this regard that ‘identifying the causality between the damages suffered by the plaintiff and the auditors’ actions is problematic’ and that ‘unlike the existing litigation practices in mature audit environments, audit standards are rarely used as a reference in Russian courts’ (p. 31). This assessment was reinforced by a series of court cases filed in 2001–2002 by a number of minority shareholders of a Russia’s energy giant Gazprom against the company’s auditor PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC). The shareholders accused PwC of approving several deals that allegedly resulted in asset losses worth billions of US dollars and of having issued a misleading audit opinion. The Moscow Arbitration Court, however, did not consider the quality of the audit work and whether it was up to ‘standard’, but rejected the claims on the basis that it was not the company’s shareholders but its management that entered into the agreement with the auditor (for a discussion, see Korchagina 2002).

6.4 The Uneasy Task of Harmonising Auditor Liability Rules

In many areas of financial reporting and audit regulation, a common approach to dealing with national diversity has been to contemplate attempts at reducing it through processes of standardisation and harmonisation. Indeed, the promotion of international standards and the harmonisation of practice across nations has very much become the norm in today’s globalised world, with cross-country variation increasingly represented as an obstacle to economic integration and growth and certainly not an aid to the promotion of corporate transparency and accountability. Clear evidence of such a trend lies in the global standards and codes advocated by bodies such as the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and the World Bank/IMF. In the field of accounting and auditing, the growing international recognition of the work of the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board (IAASB) reflect the significance global commitment to the harmonisation of accounting and auditing practices. Similar cooperative commitments in relation to the issue of auditor liability issue can be seen to be particularly relevant given that the nature of liability risks faced by the audit profession, and specifically the large international audit networks, extend across national boundaries and is no longer unique to any one specific national environment. However, the success in signing countries up to the global adoption of international accounting and auditing standards stands in some contrast to the level of success that has been achieved in terms of harmonising national regimes of auditor liability. An illustration of the problems that have been encountered in this area is now provided by reviewing the attempt to harmonise national auditor liability regimes within the context of the European Union (EU).

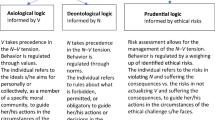

In 2007, a public consultation was launched (Directorate General for Internal Market and Services 2007a) to collect stakeholder views on the need for and appropriate methods of limiting auditor liability. The documents resulting from the consultation process, such as the response letters and the EU reports interpreting these responses, are striking in that they demonstrate significant differences of opinion across key stakeholder groups. The audit profession was virtually the only group of respondents that expressed a unanimous support for some form of auditor liability limitation. Other interest groups, however, demonstrated far less unity on the subject of auditor liability limitation. Importantly, as Fig. 6.1 shows, the variation in views on the need for limited liability and various mechanisms for delivering such limitation attributable to their different national origin and the nature of auditor liability regimes adopted in their respective countries.

Stakeholder views based on the country of origin. Source Directorate general for internal market and services 2007b, p. 7

Specifically, the investment community argued that the case for reform at the EU level had not been made as there was no convincing evidence to suggest that the existing levels of litigation could bring down an audit network. Furthermore, there was a clear split in opinions submitted by members of the banking sector, with French representatives strongly rejecting a need for any form of liability limitation while representatives of other Member States expressed a view that such limitation was beneficial in terms of improving audit choice. For the French banking community, limiting liability was anticipated as having a detrimental effect on audit quality and was not an appropriate way of dealing with current levels of audit market concentration. The response of European corporate also lacked uniformity with members of the French corporate sector opposing the reforms, while companies from the countries where liability cap had been introduced (such as Germany) expressing views in support of limited liability.

Significantly, the opinions of individual Member States’ governments and regulatory agencies failed to demonstrate a united front as to whether or not auditor liability should be limited and, if so, what was the most suitable limitation method. In their response letter, the Swedish Supervisory Board of Public Accountants, for example, refrained from explicitly commenting on the proposed nature or appropriateness of the liability reform proposed by the EU and simply stated its belief that any regulatory action should be based on some general principles rather than on detailed provisions (Directorate General for Internal Market and Services 2007b). Also, the Swedish Ministry of Justice stressed that the European Commission should introduce new regulatory measures only if they impose no restrictions on individual Member States’ decisions as to the most appropriate mechanism for implementation, noting that the Swedish government had previously undertaken its own study looking into how best to limit auditor liability. Furthermore, the Finnish government’s Ministry of Trade and Industry made reference to a similar type of a country-wide study published in 2006 and suggested that, in the context of the EU as a whole, the ability of the Member States to change the existing liability regimes was not sufficiently well understood and hence, there was a need for further investigation and analysis before any decision was made at the EU level. And finally, representatives of French regulators demonstrated strong opposition to regulatory reform that would lead to any form of limited liability.

In highlighting the evident challenges of achieving a single pan-European policy solution on the issue of auditor liability, this observed lack of consensus arguably influenced the EU’s subsequent actions and the content of the proposed policy measures. Specifically, in its Recommendation published in 2008 (European Commission 2008), following the aforementioned consultation, the EU did recommend that national laws in Member States supporting ‘joint and several’ liability should be replaced with provisions introducing a form of limited liability, such as a liability cap, proportionate liability or limitation by contract between an auditor and the client. However, while formally placing the emphasis on the need for harmonisation, the Recommendation effectively let Member States select the appropriate method out of a wide range of proposed options. Further, unlike EU Directives, Recommendations impose no legal obligation upon Member States to take action but merely provide an encouragement to do so and hence do not need to be followed by the so-called comitology process designed to oversee the implementation of the new law. Therefore, as Humphrey and Samsonova (2012) argue in a detailed analysis of the pursuit of auditor liability limitation in the EU, the fact that the regulatory response was framed in the form of a recommendation effectively suggests that the EU had refrained from fully addressing the problem of national diversity of liability regimes in Europe.

6.5 A Struggle over Liability or Identity?

The above discussion has vividly illustrated the problematic nature of the issue of auditor liability in terms of both the sheer degree of variation in the national approaches to such an issue and difficulties of achieving a policy solution which would be deemed satisfactory for different stakeholders and in relation to different environments. In many respects, a struggle to find such a solution is akin to a struggle to reconcile the diverse opinions and standpoints as to the nature of the auditor’s identity and the social value of audit. Humphrey and Samsonova (2012) have argued that auditor liability should be viewed as not merely a mechanism for restraining auditor behaviours but, in a broader sense, as an instrument of social control whose functionality is determined with reference to some more fundamental values and norms adopted in the institutional environment where such an instrument is employed—such as the general role that auditing plays in a society, context-specific understandings of social justice and accountability, the influence of the state on shaping the notions of audit professionalism, and others. Variation in liability rules across countries may therefore be seen as an indication of the extent to which national actors have different views as to the identity and roles that should be attributed to an auditor in terms of maintaining important functional and social values and norms. In other words, the emphasis and punitive strength of auditor liability arrangement may be less in less litigious settings not simply because of a lower risk of litigation, but also because of the relatively lower level of importance that such a society places on auditing in comparison to, for example, government oversight. In this respect, Humphrey and Samsonova (2012) view auditor liability as part of ‘a broader system of accountability’ and argue that ‘strict and punitive systems of public oversight over auditors (regulatory accountability), the strong collegial effects of peer pressure on auditors’ daily routines (peer accountability) or the extent and effectiveness of criminal liability for intentional negligent conduct by auditors can greatly diminish the significance of civil liability as a key mechanism to guide and discipline auditor behaviour’ (p. 49).

If appreciation of differences in contextualised understandings of audit objectives can help better understand the roots of the persistent variation in the countries’ auditor liability regimes and, as the case of the EU shows, the challenges of harmonising such regimes, the question has to be asked as to what are the most appropriate policy responses going forward? The chapter has illustrated the wide spectrum of opinions on the appropriate scope of liability exposure and perceived need for liability limitation among various stakeholder groups. In many ways, such a state of affairs may be seen as a reflection of an equally long-standing debate regarding the existence of an audit expectations gap. Just as we may debate whether auditors are delivering audits of the quality expected and desired by users of audit services and whether they should be providing additional functions and services, we can discuss whether auditors should be responsible to a narrower or broader range of stakeholders, whether litigation claims against auditors are ‘fair’ or ‘punitive’, and whether audit firms are commercially powerful and successful or highly vulnerable to the vagaries and catastrophes of legal action.

It may be appropriate to see the EU’s Recommendation as a staging post from which the profession globally can build a stronger case for (further) liability limitation. Alternatively, it may be that the relative silence at EU levels on this issue, post the Recommendation, suggests that any sense of advancement by the profession towards its desired goals, is overstated. It could even be argued that the debate is no closer to a conclusion and that seeking a set of liability arrangements that would be deemed appropriate to all parties involved, including auditors and users of their services, remains a monumental and, probably, an impossible task. Over the years, we have seen auditor liability discussed from various perspectives reflecting different sets of priorities and interests. The range of arguments developed in the course of such discussions has varied, from those advanced by an audit profession that sees liability limitation as the key for tackling the problems of poor audit judgement and defensive audit behaviour (effectively trading limited liability for promised improvements in audit quality) to those emphasising limitation as a way to reduce entry barriers for smaller audit firms and hence address the problem of audit market concentration. While the basic logic behind such arguments has been substantially questioned by critics suggesting that the profession has overstated the scale and seriousness of its liability exposure (in the form of realised court decisions against auditors) (e.g. see Gwilliam 2004, 2006), may be the key message to take from such discussion is to shift the policy focus from trying to come up with ‘the best’ or the ‘least bad’ solution for the liability problem and to give more attention to fundamental questions about auditing and the achievements of audit practice. Rather than being a subject in which energy and attention is devoted to the identification of an all-embracing solution, auditor liability limitation should be seen as opportunity for gaining greater understanding of the achievements, lived experiences and expectations of (and those held for) auditors.

Arguably, one of the reasons as to why the liability debate is still alive is because there continues to be a lack of clarity in the minds of the public as to what it is that auditors do and the particular social identity and functioning of audit. Instead of debating whether or not limiting auditor liability is an effective means of tackling issues of audit quality, audit market concentration or something else, one should reverse such a debate to consider how addressing such issues may in turn help tackle the liability dilemma. In other words, there is a chance that continued efforts to improve audit standards, standards’ compliance as well as the visibility of the audit process may lead to the long-running liability saga solving itself. This is not an easy policy route or one guaranteed to deliver concrete results. But it has one distinct advantage—in that we arguably know much less about differences in the social significance and achievements of audit practice than we do about differences in auditor liability regimes.

It has been suggested on numerous occasions that the best form of liability limitation is quality auditing work—after all, no court is going to find auditors liable for having done a good audit! The conundrum highlighted by the profession is that demanding regulatory and punitive liability regimes are said to engender a form of audit that is more rigid and less embracing/trusting of the very professional judgement that makes for a quality audit. Accordingly, it is claimed that the best, preventive, forms of liability limitation cannot come without first securing legislative liability limitation. But, such legislative reform is not going to come (and has not come) when the complainants are seen to be massively commercially successful organisations or when their case is seen as being based on cross-country liability regime comparisons in which the role of, and respect for, audit varies significantly. In this respect, the underlying crisis that auditors face is not one of liability per se, but as mentioned earlier, one of professional identity and achievement. It is one thing for the audit profession to claim a commitment to serving the ‘public’ interest, but to secure desired liability reform, this commitment is going to have to be suitably recognised and appreciated not only by the ‘public’ but also the profession itself. This is not to say that there will ever be one blanket-styled reform of auditor liability that is suitable in all national jurisdictions and contexts. Indeed, it may well be that the issue of auditor liability is a moving feast, a polemic that shifts in focus and emphasis as social demands, expectations and social contexts change. However, it is always likely to be the case that the more that is known of the world of auditing, the achievements and lived experiences of auditors and those to whom auditors are accountable, the more chance there is that liability regimes will be socially ‘fit for purpose’.

Notes

- 1.

See ‘A shared shield’, ACCA website (www.accaglobal.com/en/member/cpd/auditing-assurance/planning/sharper-shield.html).

- 2.

In the first case, Ernst and Young and its former client services partner, Kevin McNamara, were initially held responsible in 2008 for more than 20 instances of a lack of professional competence during an audit of Equitable Life and fined £4.2 m. However, after the appeal, the initial ruling was overturned and the fine reduced to £500,000. In the second case, the creditors of the New Century, America’s second largest subprime lender which collapsed in April 2007, claimed that KPMG’s audits were ‘recklessly and grossly negligent’. Such an assessment was also echoed in the 2008 report prepared by the US Department of Justice appointed examiner Michael Missal. This argued that KPMG contributed to the New Century’s failings ‘in critical ways’, for example, by suggesting alternative methods for calculating the company’s reserves needed to cover defaulting loans. In July 2010, it was reported, however, that the lawsuit was resolved in a settlement where KPMG LLP was required to pay $44.75 m. Such appeals and associated settlements, though, have not tended to quell the level of debate, with critics of the profession in the press expressing a sense of bafflement at how auditors could not have a certain degree of responsibility for failing to spot scandals of the magnitude of, for example, the Equitable Life case (e.g. see Ruth Sutherland in her article in the Observer (6/10/10) entitled “Equitable case shows it’s time for regulators to bring auditors to book” (see http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/jun/06/equitable-life-ernst-and-young).

- 3.

See ‘Hands off the auditors’ ‘deep pockets’, Financial Times, 12 October 2005. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/102da602-3b85-11da-b7bc-00000e2511c8.html

- 4.

Such a regime means that any audit partner accused of wrongdoing can be required to pay the entire amount of damages irrespective of whether the damages were caused by the unprofessional audits or by the wrongdoing of other parties, such as the company’s management.

- 5.

Proportionate liability is a regime where an auditor can be asked to compensate for the damages caused but only in proportion to the degree of his/her culpability.

- 6.

See an evidence statement by Lee White, a Chief Executive Officer at the Australian Institute of Chartered Accountants, made as part of the enquiry led by the Select Committee on Economic Affairs of the British House of Lords into audit market concentration in the UK in November 2010 (House of Lords 2010, p. 151).

- 7.

The case became the first in the US history where criminal charges were brought against auditors who were found guilty of conspiracy even though they did not personally benefit from providing unprofessional audits. Specifically, the jury accused the auditors of having made a false and misleading statement by having inappropriately issued an unqualified opinion on fraudulent financial reports prepared by the Vending Machines.

- 8.

A series of major law suits is widely cited as having led to the Chap. 11 bankruptcy filing by Levanthol Horwath in November 1990, which prior to its collapse had been the seventh largest audit firm in the US.

- 9.

In the US, apart from the PSLRA, examples of other key pieces of legislation covering the issue of auditor liability include relevant sections of the Securities Act of 1933, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) enacted in 1970. Section 10(b) of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act, for example, which is used most frequently as a basis upon which the damaged parties bring federal suits against auditors, deems it unlawful to use ‘any manipulative or deceptive device in contrivance of ··· (the securities) rules and regulation as the (Securities and Exchange) Commission may prescribe as necessary or appropriate in the public interest or for the protection of investors’. In addition, section 11 of the 1933 Securities Act gives the parties affected as a result of unprofessional audits a right to take action against an auditor of a company that files a registration statement that contains ‘an untrue statement of a material fact or omitted to state a material fact’. Both sections place the burden of proving the materiality of misstatements and the causality between such misstatements and the losses incurred on the plaintiffs themselves.

- 10.

See, for example, ‘Auditor liability deals blocked’, Financial Times, 11th March 2009.

References

ACCA (2011) Audit reform: aligning risk with responsibility. Report. May. London: ACCA.

Accountancy Age (1993). Big firms lead push to cap audit liability, 1.

Accountancy Age (1994a). Audit liability campaign shifts to public interest, 10.

Accountancy Age (1994b). Audit liability—we are not crying wolf this time, 10.

Accountant (2003) Urgent need for liability reform. 25th April, 2.

Al-Shawaf, H. T. (2012). Bargaining for salvation: how alternative auditor liability regimes can save the capital markets. University of Illinois Law Review, 2012, 501–536.

Andersen A & Co., (1992) Coopers and Lybrand, Deloitte and Touche, Ernst and Young, KPMG Peat Marwick, price waterhouse, the liability crisis in the United States: impact on the accounting profession. Journal of Accountancy, 174(5): 19–23.

Baker, C. R., & Prentice, D. (2007). The evolution of auditor liability under common law. Journal of Forensic Accounting, 8, 183–200.

Baker, C. R., & Prentice, D. (2008). The origins of auditor liability to third parties under United States common law. Accounting History, 13, 163–182.

Brewster, M. (2003). Accountable: how the accounting profession forfeited a public trust. New Jersey: Wiley.

Carey, J. L. (1965). The CPA plans for the future. New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants.

Center for Audit Quality (2008a). Report of the major public company audit firms to the department of the treasury advisory committee on the auditing profession. http://www.thecaq.org/publicpolicy/data/TRData2008-01-23-FullReport.pdf.

Center for Audit Quality (2008b). Comment letter by Cynthia M. Fornelli, executive director, regarding draft report addendum 17–19. http://comments.treas.gov/_files/CAQCommentletter62708FINAL.pdf.

Chung, J., Farrar, J., Puri, P., & Thorne, L. (2010). Auditor liability to third parties after Sarbanes-Oxley: an international comparison of regulatory and legal reforms. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 19, 66–78.

Cousins, J., Mitchell, A., & Sikka, P. (1999). Auditor liability: the other side of the debate. Critical Perspectives of Accounting, 10, 283–312.

De Poorter, I. (2008). Auditor’s liability towards third parties within the EU: a comparative study between the United Kingdom, the Netherland, Germany and Belgium. Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology, 3(1), 68–75.

Directorate General for Internal Market and Services (2007a). Commission staff working paper: consultation on auditors’ liability and its impact on the European capital markets. Brussels: European Commission.

Directorate General for Internal Market and Services (2007b). Consultation on auditors’ liability: summary report. Brussels: European Commission.

Ernst & Young (2008).Comment letter regarding draft report and draft report addendum 25–26.

Financial Reporting Council (2008), Guidance on Auditor Liability Limitation Agreements, London: FRC, June 2008. See http://www.frc.org.uk/about/auditorliability.cfm

Gietzmann, M. B., & Quick, R. (1998). Capping auditor liability: the German experience. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23(1), 81–103.

Gietzmann, M. B., Ncube, M., & Shelby, M. J. (1997). Auditor performance, implicit guarantees, and the valuation of legal liability. International Journal of Auditing, 1(1), 13–30.

Giudici, P. (2010). Auditors’ roles and their multi-layered liability regime. Working paper. Italy: Free University of Bozem-Bolzano.

Gwilliam, D. R. (2004). Auditor liability: law and myth. Professional Negligence, 20(3), 172–181.

Gwilliam, D. R. (2006). Audit quality and audit liability—a musical vignette. Professional Negligence, 22(1), 37–52.

Hill, J., Metzger, M., & Wermert, J. (1994). The spectre of disproportionate auditor liability in the savings and loan crisis. Critical Perspective on Accounting, 5(2), 133–177.

House of Lords (2010). Auditors: market concentration and their role. Volume II: Evidence. London: House of Lords.

Humphrey, C., & Samsonova, A. (2012). Transnational governance in action: the pursuit of auditor liability reform in the EU. Working paper. Manchester Business School, UK: University of Manchester.

ICAA (1995). Opportunity, equity and fairness. Edmonton: Institute of Chartered Accountants of Alberta.

Knapp, M. (2011). Contemporary auditing; real issues and cases. South-Western, USA: Mason.

Koch, C. W. & Schunk, D. (2009). Limiting auditors’ liability? - experimental evidence on behavior under risk and ambiguity. Working paper. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=982027.

Kohler, A.G., Marten, K-U., & Quick, R. (2008). Audit regulation in Germany: improvements driven by internationalization. In R. Quick, S. Turley, & M. Wilekens. (Eds.) ‘Auditing, trust and governance: developing regulation in Europe’. Routledge: London: 111–143.

Korchagina, V. (2002). Big five discuss auditing problems. The Moscow Times.

Lys, T. (2005). Discussion: the evolution of lawsuits against auditors—determinants, consequences, and solutions. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 2(3), 427–433.

Mahoney, P. G. (2009). The development of securities law in the United States. Journal of Accounting Research, 47(2), 325–347.

Merino, B. D., & Kenny, S. Y. (1994). Auditor liability and culpability in the Savings and Loan industry. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 5(2), 179–193.

Minow, N.N. (1984). Accountants’ liability and the litigation explosion. Journal of Accountancy 70.

Napier, C. (1998). Intersections of law and accountancy: unlimited auditor liability in the United Kingdom. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23(1), 105–128.

O’ Malley, S. F. (1993). Legal liability is having a chilling effect on the auditor’s role. Accounting Horizons, 7(2), 82–87.

Oberly, K. (2008). Written testimony of Kathryn, A. Oberly (Americas Vice Chair and General Counsel, Ernst & Young LLP) before the Federal Advisory Committee on the Auditing Profession to U.S. Department of the Treasury. http://www.ustreas.gov/offices/domestic-finance/acap/submissions/06032008/Oberly060308.pdf.

Pacini, C., Hillison, W., & Sinason, D. (2000). Auditor liability to third parties: an international focus. Managerial Auditing Journal, 15(8), 394–406.

Palmrose, Z. (1997). Audit litigation research: do merits matter? an assessment and directions for future research. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 16, 355–378.

Puri, P., & Ben-Ishai, S. (2003). Proportionate liability under the CBCA in the context of recent corporate governance reform: Canadian auditors in the wrong place at the wrong time? Canadian Business Law Review, 39, 36–50.

Quick, R., Turley, S., & Wilekens, M. (2008). Auditing, trust and governance: developing regulation in Europe (pp. 205–222). London: Routledge.

Roach, L. (2010). Auditor liability: liability limitation agreements, working paper. UK: University of Portsmouth.

Roberts, R. W., Dwyer, P. D., & Sweeney, J. T. (2003). Political strategies used by the US public accounting profession during auditor liability reform: the case of the private securities litigation reform act of 1995. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22, 433–457.

Samsonova, A. (2012). Local sources of a differential impact of global standards: the case of international standards of auditing in Russia, working paper. UK: Manchester Business School, University of Manchester.

Scherl, J. (1994). Evolution of auditor liability to noncontractual third parties: balancing the equities and weighing the consequences. The American University Law Review, 44, 255–289.

Sikka, P. (2008). Globalization and its discontents: accounting firms but limited liability partnership legislation in Jersey. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 21(3), 398–426.

Siliciano, J. A. (1997). Trends in independent auditor liability: the emergence of a sane consensus? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 16(4), 339–353.

Sunday Times (2004). Big four battle liability laws. 2nd May; 8.

Talley, E. L. (2006). Cataclysmic liability risk among big 4 auditors. Columbia Law Review, 106(7), 1641–1697.

Thornton G. (2008). Comment letter regarding draft report and draft report addendum 4. http://comments.treas.gov/_files/GTCommentlettertoACAPJune2008_FINAL.p.

Turley, S. (2008). Developments in the framework of auditing regulation in the United Kingdom. In Quick, R., Turley, S. and Wilekens, M. (Eds.) Auditing, Trust and Governance: Developing Regulation in Europe. London: Routledge; 205–222.

Ward, G. (1999). Auditors’ liability in the UK: the case for reform. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 10(3), 387–394.

European Commission (2008). Commission recommendation of 5/VI/2008 concerning the limitation of the civil liability of statutory auditors and audit firms, 2008/473/EC. Brussels: European Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Humphrey, C., Samsonova, A. (2014). A Crisis of Identity? Juxtaposing Auditor Liability and the Value of Audit. In: Di Pietra, R., McLeay, S., Ronen, J. (eds) Accounting and Regulation. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8097-6_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-8097-6_6

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-8096-9

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-8097-6

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)