Abstract

What does it look like when an organization tentatively steps away from an exclusively rules-based regime and begins to attend to both rules and principles? What insights and guidance can ethicists and ethical theory offer? This paper is a case study of an organization that has initiated such a transition. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) has begun a turn toward the promotion of ethical principles and best practices by adding a “conceptual framework” to its existing Code of Professional Conduct (Code). This conceptual framework calls upon its members to intentionally increase their awareness of significant threats to their compliance with its rules of conduct and to establish safeguards to offset or eliminate those threats. To this end, each member is required to regard every questionable situation, circumstance, transaction or relationship by attempting to view it through the eyes of an imagined reasonable third party. This paper examines this protocol theoretically and practically. First, we frame this analysis within the principles and ethical concepts that inform the professional ethics of accountants. Second, we critique the AICPA’s long-standing rules-based approach to its Code. Third, we examine the new conceptual framework with a view toward its potential for the promotion of a more principles-based approach to the professional ethics of the accounting profession. Fourth, we give attention to the notion of the “reasonable and informed third party,” which has been embedded in the new conceptual framework, and consider how two schools of thought—Adam Smith’s modernist “impartial spectator” concept and Emmanuel Lévinas’ postmodern phenomenology in regard to “the Other”—may offer theoretical support and clarity for this epistemic exercise. Finally, we point out several ways in which the AICPA’s commitment to its new conceptual framework could be strengthened and enhanced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has become commonplace for ethicists to criticize businesses and other organizations for adhering to a rules-based ethical regime rather than one that takes into account both rules and principles (e.g., Spalding and Oddo 2011; Arjoon 2006, 2007). Osiemo (2012) articulates this notion in typical fashion when she observes that “[T]he fall of large international corporations in the recent past as a result of acts of gross professional negligence and fraud has made it clear that what is needed to prevent such ethical failures is a corporate culture rooted in ethical and responsible behavior more than laws and rules restricting what people should or should not do in the work place” (p. 138).

What does it look like when an organization begins to take steps away from a solely rules-based regime and begins to attend to both rules and principles? Are there insights and guidance that ethicists and ethical theory can offer to an organization as it begins such a transition? This paper proffers this case study as an example of one possible way in which ethical theory and analysis might be brought to bear in a context involving an organization’s efforts to improve its ethical constitution and culture.

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) has for decades maintained and implemented a rules-based approach to its Code of Professional Conduct (Code) (AICPA 2016). Although the Code has since 1972 included prefatory language about principles, the AICPA’s bylaws make it clear that only the actual rules of the Code are taken into account when investigating or disciplining members for Code violations (AICPA 1988). This rules-only enforcement of the Code has been the subject of some criticism over the last two decades, including calls for changes that would result in the improvement of ethical decision making rather than the mere enforcement of rules (Spalding and Oddo 2011; Collins and Schultz 1995; Preston et al. 1995).

After publication of the 2013 version of its Code (AICPA 2013), the AICPA embarked on a project to codify and update its ethical standards. This project did not result in any substantive changes to its rules and interpretations, but the organization added a “conceptual framework” to its Code, effective December 15, 2015. This conceptual framework emulates the conceptual framework of the Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants (COE) promulgated by the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA 2016), an independent standards-setting body of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC). The AICPA conceptual framework requires its members to intentionally increase their awareness of threats to their compliance with the profession’s rules of conduct and to establish safeguards to offset and/or eliminate those threats that are deemed to be significant. Professionally active AICPA members are now required to examine every questionable situation, circumstance, transaction or relationship by attempting to view it through the eyes of an imagined reasonable third party.

For each such circumstance, the accountant must consider whether this imaginary onlooker would likely find the member at risk of noncompliance (even if the member is technically in compliance) with one or more professional ethics rules. If so, steps must be taken by the member to safeguard himself or herself from the potential rule violation by reducing this perceived risk. However, neither the AICPA nor the IFAC has offered theoretical support or grounds for the notion of requiring accountants to imagine and consider the presumed expectations of an impartial spectator as an ethics-related risk management technique.

This paper critiques the new AICPA conceptual framework. First, we frame this analysis within the principles and ethical concepts that inform the professional ethics of accountants. Second, we critique the AICPA’s long-standing rules-based approach to its Code. Third, we examine the new conceptual framework with a view toward its potential for the promotion of a more principles-based approach to the professional ethics of the accounting profession. Fourth, we give attention to the notion of the “reasonable and informed third party,” which has been embedded in the new conceptual framework, and consider how two schools of thought—Adam Smith’s modernist “impartial spectator” concept and Emmanuel Lévinas’ postmodern phenomenology in regard to “the Other”—may offer theoretical support and clarity for this epistemic exercise. Finally, we point out several ways in which the AICPA’s commitment to its new conceptual framework could be strengthened and enhanced.

Accountants’ Accountability to Others

Accountability of Accountants Generally

Society relies on accountants. As the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB 1978) has observed:

Many people base economic decisions on their relationships to and knowledge about business enterprises and thus are potentially interested in the information provided by financial reporting. Among the potential users are owners, lenders, suppliers, potential investors and creditors, employees, management, directors, customers, financial analysts and advisors, brokers, underwriters, stock exchanges, lawyers, economists, taxing authorities, regulatory authorities, legislators, financial press and reporting agencies, labor unions, trade associations, business researchers, teachers and students, and the public (p. CON1-8).

Every organization that receives funds from investors and creditors has an essential fiduciary duty, and often a legal duty, to be accountable for those funds. For-profit corporations managed by boards of directors, partnerships operated by general partners, limited liability companies functioning under the helm of managing members and virtually every other type of organization in which investors place their trust and their funds are called upon to account for such investments.

Accountants also serve in roles other than auditors or reviewers of financial statements, or preparers of tax returns. Managerial accountants, for example, assist organizations from the inside, serving as comptrollers, tax executives, internal auditors, chief financial officers (CFOs) and senior executives. These internal accountants play a key role in constructing, managing, maintaining and extracting information from organizational accounting information systems, and making that information available to upper management, external auditors and others. While society at large might not seem as directly dependent upon these insider professionals, as it might be on their public accounting counterparts, there is an indirect reliance on the information they generate.

As Shearer (2002, p. 542) observed, “the triumph of free market capitalism on a global basis has elevated the need for economic accountability to a pressing social concern.” Bayou et al. (2011) see this role of accountability in terms of structured narrative or codified discourse that provides a particular rendering of an entity’s circumstances, be it a business firm, a government, a nongovernmental organization or a citizen/taxpayer:

[T]he organizing theme of this structured narrative has throughout history been accountability, the giving of an account of one’s actions. Thus, the narrative of accounting is focused on responsibilities fulfilled or not fulfilled; it is a narrative that has historically been intended to provide the reliable memory about the important events that occurred in the past in order to determine what are the consequences up to now, whether they be for purposes of levying a tax, rewarding performance, ending someone’s employment, or, perhaps, determining criminal behavior (p. 118).

Codes of ethics help to promote and maintain legitimacy (moral, strategic or otherwise) when they are accompanied by compelling reasons for compliance by the professionals concerned (Neu and Saleem 1996). Professional codes should educate the members of the profession about its enduring principles, but to be effective professional codes should increase members’ awareness and cause them to question their adherence to the profession’s values (Higgs-Kleyn and Kapelianis 1999). A code’s value to the profession and to society is directly related to the extent to which it guides, circumscribes, influences and informs behavior. As Askary and Olynyk (2006, p. 52) warned, self-regulation is “a privilege granted to a professional association for only as long as society has confidence in the association’s regulatory processes.” A robust concept of, and appreciation for, the profession’s duty to the public serves both well (Dellaportas and Davenport 2008). Both sides of the social contract between the public and the public accounting profession benefit, which is why society grants power and privilege to the profession based on the ability and willingness of the latter to contribute to the broader values and needs of the former (Gilbert and Behnam 2009; Frankel 1989).

AICPA Principles of Professional Conduct

The AICPA acknowledges the profession’s social obligations in the preface to its Code, which lists six principles that “express the profession’s recognition of its responsibilities to the public, to clients, and to colleagues” (AICPA 2016, p. 3). Those principles include:

-

(a)

Responsibilities principle, which acknowledges that members of the profession “should exercise professional and moral judgments in all their activities.”

-

(b)

Public interest principle, which calls for members of the profession to “act in a way that will serve the public interest, honor the public trust and demonstrate a commitment to professionalism.”

-

(c)

Integrity principle, which suggests that by performing all professional responsibilities with the highest sense of integrity, members of the profession will “maintain and broaden public confidence.”

-

(d)

Objectivity and independence principle, which emphasizes the need for objectivity in the performance of all services and the maintenance of the fact and appearance of independence in all attestation engagements.

-

(e)

Due care principle, which challenges members of the profession to discharge professional responsibilities with competence and diligence.

-

(f)

Scope and nature of services principle, which calls for accountants in public practice to observe the other five principles of the Code when determining the scope and nature of services to be provided.

All six of these principles share two common characteristics: First, they point to the highest levels of professionalism; and second, they are merely advisory. With regard to the latter, the AICPA bylaws clearly specify that only noncompliance with specific rules is enforced by the organization (AICPA 1988). The principles have no authoritative weight under the current regime. They are aspirational only and are not taken into account for purposes of oversight or discipline of members by the AICPA.

As early as 1972, the above-described principles (originally referred to as “concepts of professional ethics”) were included as a preface to the Code’s rules (AICPA 1972; Higgins and Olsen 1972), but they have never served as more than an introductory backdrop to the rules. Brown et al. understood the articulation of these principles as exemplifying a strategy of “self-presentational behaviors designed to convey an image of integrity and trustworthiness” in an effort to be perceived as “morally worthy” (2007, p. 42). Preston et al. (1995) succinctly described the relationship between the AICPA’s nonbinding statement of principles and its mandatory rules as follows:

[B]y adopting legalistic rules the profession did not entirely surrender its moral elements, but these were relegated to the principles section. Whereas the principles are what the professional accountant must aspire to, it is the rules that he or she must obey (Preston et al., p. 527).

AICPA Code of Professional Conduct

Traditional Rules-Based Aspect of the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct

Despite the AICPA Code’s prefatory gesture toward principles, the AICPA has traditionally confined itself to a rules-based approach to professional ethics. This observation was made by the Auditing Standards Committee of the Auditing Section of the American Accounting Association, which agreed with Spalding and Oddo (2011) that the AICPA’s Code is largely rules-based and instead should more closely conform to the IESBA’s principles-based ethical standards (Gaynor et al. 2015, p. C14). This has been the case since AICPA’s first lists of rules of professional conduct, such as the list of eight rules issued in 1917 (American Institute of Accountants 1917).

The Code contains 11 basic rules applicable to all members of the AICPA or of state associations of certified public accountants (CPAs), who are in public practice (AICPA 2016). Separately, members who work in and for business organizations instead of public accounting firms, are subject to five of the 11 basic rules and are not affected by rules pertaining to such matters as fees, advertising and form of organization. All of the rules are supported by a myriad of interpretations and supporting pronouncements.

As noted above, the AICPA bylaws provide for the enforcement of its ethics rules. State associations of CPAs have an identical requirement. When allegations of possible rule violations come to the attention of the AICPA or a state-level affiliate, the respective ethics committee investigates the matter. If violations to one or more rules are confirmed, the organization may impose various disciplinary actions, ranging from remedial ethics training to suspension or termination of membership. State CPA societies have procedures that apply to local allegations of rule violations and also participate in a joint ethics enforcement partnership program with the AICPA. All of these procedures and programs are voluntary—unlike the regulatory actions of state boards of accountancy that issue and oversee CPA licenses and federal agencies, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) that authorize accountants to practice before their respective agencies.

Criticism of the Rules-Based Aspect of the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct

The AICPA’s adherence to a rules-based regime of professional ethics oversight has been the subject of criticism over the years. In particular, Preston et al. (1995) undertook an extensive study of the accounting profession’s approach to professional ethics. They studied the profession’s early efforts at the turn of the twentieth century, which culminated in the adoption of a formal set of five rules in 1917. They compared this early effort to the AICPA’s re-issuance of its code of conduct in 1988. In that year, the AICPA finalized the 11 rules that now comprise the current Code (AICPA 2013, 2016). The researchers concluded in part that cultural norms at the turn of the century were such that accountants could be expected to “transform themselves into moral subjects” by finding guidance outside of the accounting profession, specifically “in a Christian upbringing and liberal education” (p. 518). In this regard, they understood “Christianity” to include a belief system that produced “an unceasing quest for a believer to improve himself to be a moral character” (p. 521). By the 1970s and 1980s, on the other hand, accountants’ ethics had become more secularized, more rationalized and more rules-based. To some extent, this transition was the result of larger cultural shifts, but it also occurred because compliance with technical standards and quality had become central to the profession and its Code.

It was the view of Preston et al. (1995) that the accounting profession maintains its Code primarily as a means for legitimizing the status of certified public accounting as a recognized and respected profession. They also observed that this Code is rules-based, meaning that it is focused on following a rule, rather than upon the personal characteristics or virtues that both lead to and reflect an ethical state of mind. They suggested that “one may argue that the role of rules may be to preserve discretion and at the same time keep the public happy” (pp. 527–528). They concluded that this emphasis on technical compliance with behavioral rules, rather than on the ongoing adherence to larger ethical principles, was to some extent a more manageable approach to the oversight of professional conduct than the more traditional (and religiously informed) emphasis on what it means to be an ethical person. Collins and Schultz (1995) characterized this tension in terms of timing: An internal AICPA disciplinary adjudication of one or more specific acts (in the past) by an individual is easier to administer than would be an effort to preclude or minimize potential (future) lapses in ethical behavior.

Neill et al. (2005) pointed out that in the process of developing and maintaining a rules-based code, the AICPA has adopted a management-by-exception approach that is heavily dependent upon complaints and grievances made by clients, employers, government agencies and other third parties. This “input-based” approach, as they described the process, did not afford any external, objective or third-party assessment of compliance with the Code. Indeed, the AICPA itself has not required any system of ongoing assessment of members’ professionalism or ethics except as described below in connection with its peer review program. The observations made by Neill et al. agree with those of Arjoon (2000), who concluded in part that codes of conduct “are only as effective as the willingness of those who comply strictly with them, and without the appropriate preconditions, they tend to be regressive in so far as looking backwards to past errors” (p. 160). As Melé (2005, p. 98) pointed out, rules-based systems promote a mechanistic, legalistic pragmatism that confuses rule compliance with ethical principles.

Neill et al. (2005) also noted that the organization’s mandated peer review procedures do not address the extent to which an accounting professional or public accounting firm complies with the principles and rules included in the AICPA Code, but instead respond only to allegations of rule violations. Velayutham (2003) considers this reactive approach to enforcement, albeit for purposes of discouraging noncompliant actions by other member accountants, to be emulative of a quality assurance model that relies on specific, measurable events that includes an economic cost–benefit sort of pragmatism. By comparison, Velayutham advocates an ethics model that would give proper attention to the personhood of moral agents, including their moral attitudes and their philosophical and metaphysical notions about morality. He suggests that “the primary interest of ethics is the feelings, interest and ideals of sentient beings while quality is focused on products and services,” and suggests that some accountants’ codes of ethics should properly be referred to as “codes of quality assurance” (p. 501).

The tendency to gravitate toward the outer parameters of permissible behavior was described by Spalding and Oddo (2011) in their critique of the AICPA’s rules-based approach to ethics. They observed that instead of promoting the virtues and character traits to which individual accountants should aspire, the AICPA’s Code has had as its primary objective the mere avoidance of noncompliance, “with the hope that by minimizing noncompliance within the organization, the overall ethos of the profession will be improved” (p. 57). As a possible solution, they recommended that the AICPA adopt the “conceptual framework” approach promulgated by the IESBA. They suggested that this would accomplish two important objectives: It would bring the AICPA Code into closer compliance with the IFAC COE (IESBA 2016), and it would, in their view, result in a more effective professional ethics oversight regime.

Needed: Best Practices and Virtues Instead of Mere Compliance

While the principles of the Code are an articulation of the highest aspirations, the rules of the Code represent minimal standards below which a member of the profession must not fall, if he or she wishes to avoid disciplinary action on the part of the AICPA or a state society of professional accountants. The only behaviors that are promoted by this approach are noncompliance–avoidance behaviors. Habits and practices in the pursuit of the goals articulated in the principles of the Code are not encouraged by this approach. The avoidance of vices, rather than the pursuit of virtues, becomes the ethical template.

Campbell (2015) explores the deficiencies of an organizational compliance strategy that does not actively pursue and promote an ethos of integrity and virtue. She cites Stevulak and Brown’s (2011) claim that compliance measures are necessary, but not sufficient for the development of moral character and an ethical organizational culture. Campbell also points to Paine’s (1994) observations about the extent to which a compliance strategy is much more limited than an integrity strategy that holds organizations to a more robust ethical standard. She takes into account Whetstone’s (2005) assertion that the process of acting virtuously is to align decisions to achieve an organization’s overarching purposes.

Campbell’s observations are relevant here. Virtue ethics involves and includes the notion of the practice of self-discipline (Bowman and West 2007, p. 125). This requires repetitive re-assessment of an individual’s or organization’s current status in regard to the virtues being sought and developed, and continual efforts to ensure improvement and avoid decline. Virtue ethics, as applied to the workplace and to professionalism, is also social and effectively converts the individual’s work from a mere job or career into a vocation or calling that incorporates the highest ideals and that is inseparable from the individual’s morality, character and sense of community (McPherson 2013, p. 289). Although the relationship between virtues and human flourishing dates back to Aristotle and Confucius, recent empirical research has shown that the implementation of a virtue ethics approach to organizational values and management has reliably and consistently resulted in increased performance (Beadle 2013).

A virtue is a conscientiously chosen habit of behavior, perceptiveness and mental response that is considered holistically (Barilan 2012). The aggregate of a person’s virtues constitutes that person’s character, which, in turn, signals the ultimate ends or purpose toward which that person’s life is directed. In the Western Aristotelian tradition, that ultimate purpose was sometimes understood to be a form of contentment and happiness called eudemonia. In the Eastern Confucian philosophical tradition, the notion of harmonious ultimate principle is designated as rén. Both Aristotle and Confucius (also known as Kong Qui, Kongzi or Kong Fuzi) emphasized clusters of virtues that would yield a life of harmony, contentment and humaneness.

A virtue system is a program of character development that includes: (a) a catalog of virtues or traits that promote the experience of human flourishing; (b) a system for recognizing and identifying self-destructive habits or vices; and (c) a set of disciplines for effecting ethical change in persons by promoting the identified virtues and reducing the occurrence of the identified vices (Schimmel 2000; Roberts 1988).

As West (2016) and Spalding and Oddo (2011) have observed, certain recognizable virtues are noticeably embedded in accountants’ codes of ethics. West’s taxonomy includes such virtues as courage, justice and honesty that emerge from the fundamental ethical principles of integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality and professional behavior that are articulated in the IFAC’s COE (IESBA 2016, p. 9). Spalding and Oddo map the virtues of integrity, objectivity, diligence, loyalty and professionalism more closely to this same list of fundamental ethical principles (pp. 54–56).

Ethicists, such as Whetstone (2001), contend that a virtue ethics approach “fits very well if added as a full complement to both deontological and consequentialist teleological act theories” (p. 111). Whetstone holds that adding a virtue perspective “as a complement to act-oriented perspectives can expand the scope and perspectives of ethical analysis and understanding” (p. 104). He makes no apology for this cumulative approach:

Even if the criticisms of virtue ethics cloud its use as a mononomic normative theory of justification, they do not refute the substantial benefits of applying a human character perspective – when done so in conjunction with also-imperfect act-oriented perspectives (Whetstone, p. 101).

Shaub and Braun (2014) support this notion, adding that a commitment to virtuous behavior “potentially energizes auditors’ willingness to assume their duties” (p. 9).

Preston et al. (1995, p. 520) noted that in the early years of the profession, the focus of codes of conduct and moral discourses was on member accountants’ behavior and character. Citing Dicksee (1913), they maintained that the accountant’s character was required to possess certain virtues, including, but not limited, to caution, firmness, integrity, discretion and reliability. The taxonomy of virtues today might be slightly different from Dicksee’s (West 2016; Spalding and Oddo 2011), but the concept is the same. By emphasizing habits of behavior that optimize rather than game ethical behavior, the seemingly quaint concept of a professional’s character is one that has once again become coherent and relevant. The “narrative of character” is once again seen as a more promising approach to ethics than the “narrative of technique” epitomized by a rules–compliance model (Roberts 2010).

Adding the Conceptual Framework to the AICPA Code

Threats to—and Safeguards from—Noncompliance

The Code’s new conceptual framework is comprised of a “threats and safeguards” model in the manner of the protocols promulgated by the IESBA (2016). The AICPA Code identifies seven threats that nudge the accountant toward rule violations, and recommends that when these threats occur, the accountant should develop or implement safeguards that effectively push the accountant out of the danger zone of a potential rule violation and toward the safe zone of optimal ethical behavior. The AICPA’s list of seven threats applicable to members in practice is as follows (2016, pp. 24–26):

-

10. Adverse interest threat. The threat that a member will not act with objectivity because the member’s interests are opposed to the client’s interests.

-

11. Advocacy threat. The threat that a member will promote a client’s interests or position to the point that his or her objectivity or independence is compromised.

-

12. Familiarity threat. The threat that, due to a long or close relationship with a client, a member will become too sympathetic to the client’s interests or too accepting of the client’s work or product.

-

13. Management participation threat. The threat that a member in public practice will take on the role of client management or otherwise assume management responsibilities, may occur during an engagement to provide nonattest services.

-

14. Self-interest threat. The threat that a member could benefit, financially or otherwise, from an interest in, or relationship with, a client or persons associated with the client.

-

15. Self-review threat. The threat that a member will not appropriately evaluate the results of a previous judgment made or service performed or supervised by the member or an individual in the member’s firm and that the member will rely on that service in forming a judgment as part of another service.

-

16. Undue influence threat. The threat that a member will subordinate his or her judgment to an individual associated with a client or any relevant third party due to that individual’s reputation or expertise, aggressive or dominant personality or attempts to coerce or exercise excessive influence over the member.

Accountants are required by this new model to consider all relationships and circumstances that might increase their risk of one or more rule violations, and identify those particular threats that are significant. The AICPA’s list of threats in its conceptual framework is not intended to be exhaustive, but is instructive. Once an accountant who is a member of the AICPA or a state society of accountants concludes that one or more threats are not at an acceptable level, the accountant is called upon to apply safeguards to eliminate the threat and/or reduce it to an acceptable level.

The AICPA organizes its recommended safeguards into four categories: professional, firm, client and employing organization. At the professional level, the AICPA’s suggestions include continuing education, ethics hotlines staffed or supported by professional accountants and external review of accounting firms’ internal controls, as well as professional standards accompanied by the threat of discipline. At the firm level, 26 recommendations are made, all of which involve the dedication of public accounting firms’ resources to monitor and address the various potential threats that are described in the conceptual framework. At the client level, the AICPA recommends improvements in clients’ ethical and technical environments, presumably so that the clients’ external auditors would find themselves under less pressure to bend to questionable demands by top management. These recommendations include: (a) ensuring that the tone at the top emphasizes the client’s commitment to fair financial reporting and compliance with the applicable laws, rules, regulations and corporate governance policies; (b) requiring policies and procedures to be in place to address ethical conduct; and (c) making sure that a governance structure, such as an active audit committee, is in place to ensure appropriate decision making, oversight and communication regarding the accounting firm’s services.

The AICPA’s apparent operating theory is that by promoting these kinds of safeguards at the client level, public accounting firms that provide attest services and other services will have more confidence in the information provided by the client and can expect to find fewer circumstances or relationships that would create a conflict of interest for the external accounting firm or otherwise make the external accounting firm’s work more difficult and less reliable. Similarly, at the employing organization level (for members in business), improvements in organizational policies and procedures are recommended so that AICPA member accountants find themselves under fewer pressures, and less urging, to make decisions that would place them at risk of noncompliance with the Code. As Reinstein and Taylor (2015) observed, safeguards operate as fences that help to shield accountants from temptations, pressures and opportunities to rationalize behaviors that are likely to place them at risk of noncompliance with the rules of the Code.

Compare: IFAC Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants

As noted above, IFAC has promulgated its own COE. That document contains its own taxonomy of “fundamental principles,” as well as its own conceptual framework (IESBA 2016; West 2016). Both the principles and the conceptual framework are similar to the AICPA Code, but with one critical difference: The threats and safeguards articulated in the IFAC pronouncement relate to potential noncompliance with principles, not rules.

In other words, the international approach is decidedly principles-based, while the AICPA approach remains essentially rules-based. This tension between a principles-based international standards and a rules-based standard in the USA emulates a similar tension between the largely principles-based approach to International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and the traditionally rules-based approach to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) in the USA (See Tschopp and Huefner 2015, p. 570). A significant difference, however, is the commitment made by the AICPA, as a member of IFAC, to “not apply less stringent standards” than those stated in the IFAC promulgation (IESBA 2016, p. 7). In this sense, the ethical regime is hierarchical (i.e., AICPA is required to conform to IFAC) rather than peer-to-peer as in the case of financial reporting.

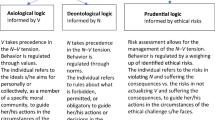

As summarized in Table 1, the AICPA’s promulgation of its conceptual framework represents a tentative step in the direction toward the principles-based approach of the IFAC COE (IESBA 2016). The conceptual framework is not “enforceable” by disciplinary actions on the part of the AICPA; thus, unlike the IFAC standard, it is essentially advisory or aspirational. As a result, the revised AICPA Code remains essentially rules-based and at best encourages the development of behaviors that safeguard against rule violations.

The Reasonable and Informed Third Party

In addition to the lists of noncompliance risks (threats) and accompanying lists of tactics to reduce such risks (safeguards), the conceptual framework introduces an epistemic exercise that involves imagining a reasonable and informed third party. Members of the profession are advised to consider each relationship and circumstances that could possibly be considered a threat. Each such relationship or circumstance that is not already explicitly addressed by a rule or interpretation within the Code is then placed under the scrutiny of an imagined onlooker, as follows:

[A] member should evaluate whether that relationship or circumstance would lead a reasonable and informed third party who is aware of the relevant information to conclude that there is a threat to the member’s compliance with the rules that is not at an acceptable level… A threat is at an acceptable level when a reasonable and informed third party who is aware of the relevant information would be expected to conclude that the threat would not compromise the member’s compliance with the rules. (AICPA 2016, pp. 26–28).

To reiterate, a threat is at “an acceptable level” if “a reasonable and informed third party who is aware of the relevant information would be expected to conclude that a member’s compliance with the rules is not compromised” (Ibid).

The AICPA does not offer a theory in support of this protocol, even though it is a common prescription within the accounting standards literature, particularly in regard to an auditor’s duty to ascertain his or her independence (Ference 2013). The Code calls for the employment of this mechanism, but without any explanation or theory that would support its use. If, for example, some members of the profession were to conclude that this epistemic exercise amounts to little more than projecting one’s own views onto an idealized third party, it yields no new or relevant information. Worse, it could result in a false confirmation of one’s own biases (Marks and Miller 1987).

Two possible theoretical underpinnings for the idea of a mental exercise—whereby an imagined reasonable and informed third party is consulted for purposes of identifying and evaluating threats to one’s compliance with ethical standards—are explored here. We look first at a modernist, Enlightenment-based characterization of an impartial spectator as articulated by Adam Smith in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (TMS) (1976). We then consider the postmodernist ideas of Emmanuel Lévinas in regard to the interpersonal and intersubjective experiencing of the Other as set forth in Totality and Infinity (1969).

There are undoubtedly other theories and resources that can contribute to this project of seeking out and coming to an understanding of a theoretical foundation for the AICPA reliance on such a device, but our goal here is to begin a discourse rather than to complete it. Our assumption is that a protocol that has at least some theoretical support will serve its objectives (i.e., the promotion of ethical reflection and deliberation) better than one without any apparent foundation.

The Gaze of Adam Smith’s Impartial Spectator

Much of the body of knowledge associated with Enlightenment-based moral philosophy and ethics, such as utilitarian and deontological schools of thought, has tended to point to rules of behavior and ethical norms (Hoover and Pepper 2015; Van Staveren 2007; Rodgers and Gago 2001). Virtue theory, on the other hand, has a much older history that Bright et al. (2014) and McCloskey (2008) trace back to Plato and Aristotle, finding a prominent place in the thinking of Cicero and the Stoics, as well as Aquinas and the Scholastics. More recently, McCloskey observes a twentieth-century resurgence of virtue as developed and addressed by such thinkers as Anscombe (1958), Foot (1978), MacIntyre (1981), Nussbaum (1988) and Hursthouse (1999). In recent business and professional ethics literature, at least since the publication of Alasdair MacIntyre’s After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (1981), there has been a similar interest in examining and considering the contributions of virtue theory (West 2016; Morrell and Brammer 2016; McPherson 2013; Francis 1990).

As part of the latter discussion about virtues and character, the notion of “impartial spectator” has emerged. This involves an epistemic exercise that draws upon the human capacity to imagine a move away from an egocentric, subjective point of view and to place oneself in the shoes of an impartial onlooker. To adopt this metaphysical perspective is to separate oneself from his or her personal emotions and self-interests and to consider a more disinterested, and arguably, more rational and balanced perspective of one’s ethical condition (Tullberg 2006, p. 76). Even though the observer is ultimately the product of the person’s intellectual imagination, the impartial spectator offers a broader perspective that more readily accommodates and encompasses the moral virtues (Gonin 2015; Forman-Barzilai 2001; Hanley 2009).

This idea of imagining—and drawing ethical implications from—an impartial observer is most often associated with Adam Smith, who developed the idea in the sixth edition of his TMS. Smith added a chapter in a later edition of that work on the character of virtue in order to argue that some values are permanent and not subject to the whims of a society (Hühn and Dierksmeier 2016).

In developing his idea of the impartial spectator, Smith adapted Hume’s theories about the connection between virtues on the part of the agent and moral approval of spectators who observe the agent’s actions (Konow 2012; Raphael 2007; Fieser 1989). Smith asserted that concern for our own happiness “recommends to us the virtue of prudence: concern for that of other people, the virtues of justice and beneficence; of which, the one restrains us from hurting, the other prompts us to promote that happiness” (Smith 1976, p. 262). He proposed an epistemic exercise involving the creation of an imaginary, indifferent spectator who is “tasked with aligning the moral sentiments of the employer class with the larger society” (Keller 2007, p. 178).

This “supposed impartial spectator” is the “great inmate of the breast, the great judge and arbiter of conduct” who “calls us to an account for all those omissions and violations, and his reproaches often make us blush inwardly both for our folly and inattention to our own happiness, and for our still greater indifference and inattention, perhaps, to that of other people” (Smith 1976, p. 262). It is from the impartial spectator “that we learn the real littleness of ourselves, and of whatever relates to ourselves, and the natural misrepresentations of self-love can be corrected only by the eye of this impartial spectator” (Smith 1976, p. 137). As we consider the viewpoint of this impartial spectator:

We endeavour to examine our own conduct as we imagine any other fair and impartial spectator would examine it. If, upon placing ourselves in his situation, we thoroughly enter into all the passions and motives which influenced it, we approve of it, by sympathy with the approbation of this supposed equitable judge. If otherwise, we enter into his disapprobation, and condemn it (Smith 1976, p. 137).

The idea of referencing an impartial spectator in order to inform one’s ethical outlook is a key component of Smith’s larger virtue theory project, which he summarizes in TMS as follows:

In treating of the principles of morals there are two questions to be considered. First, wherein does virtue consist? Or what is the tone of temper, and tenour of conduct, which constitutes the excellent and praiseworthy character, the character which is the natural object of esteem, honour, and approbation? And, secondly, by what power or faculty in the mind is it, that this character, whatever it be, is recommended to us? Or in other words, how and by what means does it come to pass, that the mind prefers one tenour of conduct to another, denominates the one right and the other wrong; considers the one as the object of approbation, honour, and reward, and the other of blame, censure, and punishment? (p. 265).

There is some debate and doubt about the extent to which Smith successfully addressed the set of questions pertaining to the first of his two basic issues (i.e., whence virtue?). Questions continue to be raised about such matters as to the extent to which excellence and praiseworthiness are notions that are culturally prescribed and somewhat relative (Demuijnck 2015; Nussbaum 1988); the nature of virtue in relation to rights and responsibilities of individuals and organizations (Szmigin and Rutherford 2013; Brown and Forster 2013); and the depiction of human nature “constantly judging and being judged from the perspective of an ‘impartial spectator’” in TMS, as compared to the more rationally self-interested understanding of human nature found in his Wealth of Nations (Hühn and Dierksmeier 2016; Smith et al. 1976).

Smith responded to his own second proposed issue (i.e., whence ethical decision making?) by developing his version of the impartial spectator concept. This notion has contributed significantly to the conversation and the body of knowledge associated with virtue theory (Raphael 2007). Hühn and Dierksmeier (2016) have observed that scholarly interest in Smith’s work has increased significantly in the last two decades, resulting in a greater appreciation for his effort to infuse moral values and virtues into public and economic life. Part of this renewed interest in Smith, and in particular his TMS, has been a revisiting of the impartial spectator mechanism as a possible technique for judging whether or not a particular interest is merely self-interested, overly selfish, just or altruistic (Bevan and Werhane 2015; Oslington 2012).

Accountants are both agent and spectator. Within the domain of accountants’ professional ethics (the focus of this paper), accountants’ own accountability can be assessed from the perspective of the impartial spectator. That observer, in turn, can not only be an imaginary avatar created for the purpose of independent self-assessment, but can be a proxy for society, that is, for the myriad of users of financial information included in the FASB list quoted above. Peters (1995) observes:

The discipline of the public gaze teaches one to see oneself as another, to view one’s passions in the dimmer light to which they appear to others, and to attain tranquility and equanimity. The gaze of impartial strangers is a school of virtue for Smith. In this respect, Smith is a model of the Enlightenment faith in publicity (or openness) as a morally regulative force. (p. 662).

Ironically, the impartial spectator’s critique of the accountant includes the extent to which the accountant, in turn, has objectively and diligently fulfilled the accountant’s own role as the observer of his or her client’s accounting and disclosure practices (Keller 2007).

The Face of Lévinas’ Other

The gaze or the face of others (or, the Other) has also gained significance in a more postmodern approach to ethical theory, especially in the writings and the work of Emmanuel Lévinas. From his perspective, the ethical does not emerge from theoretical deliberation, as such, but instead arises from the interpersonal and intersubjective experiencing of the face of the Other and an appreciation for the radical otherness of the Other (Bevan and Corvellec 2007, p. 208). In Totality and Infinity (1969), Lévinas makes the case that we learn ethics as we experience and consider our phenomenological interactions with others. For example, he observes that “I can recognize the gaze of the stranger, the widow, and the orphan only in giving or in refusing; I am free to give or to refuse, but my recognition passes necessarily through the interposition of things” (p. 77).

Lévinasian ethics is deeply personal and is discoverable as an approach to the Other that denudes us of those illusions of self-identity that encloses or encrust us (Roberts 2001, p. 111). Bauman (1993) calls this approach to ethics “re-personalizing morality,” which means “returning moral responsibility from the finishing line (to which it was exiled) to the starting point (where it is at home) of the ethical process (p. 34). It is also visual: “ethics is an optic” (Lévinas 1969, p. 23).

The ethics of Adam Smith (and much of the Enlightenment movement) primarily involves the derivation of morality through a rational process. Even the epistemic exercise that takes into account the gaze of an imagined, impartial spectator is an intentional, cognitive effort to rationally ascertain virtues and ethical principles. By comparison, Lévinas considers the gaze of the Other in more intensely personal and phenomenological terms:

The welcoming of the Other is ipso facto the consciousness of my own injustice—the shame that freedom feels for itself. If philosophy consists in knowing critically, that is, in seeking a foundation for its freedom, in justifying it, it begins with conscience, to which the other is presented as the Other, and where the movement of thematization is inverted. But this inversion does not amount to ‘knowing oneself’ as a theme attended to by the Other, but rather in submitting oneself to an exigency, to a morality. The Other measures me with a gaze incomparable to the gaze by which I discover him (p. 86).

Inferred disapproval by Smith’s imagined spectator assists the subject in the delineation of ethical norms and the articulation of virtues. Similarly, disapproval by Lévinas’ Other helps in “measuring oneself against the perfection of infinity” (p. 84). But, the locus of such disapproval for Smith and Lévinas is different. For the former, it is in the realm of moral philosophy; for the latter, it arises from the experience of shame:

Thus, this way of measuring oneself against the perfection of infinity is not a theoretical consideration; it is accomplished as shame, where freedom discovers itself murderous in its very exercise. It is accomplished in shame where freedom at the same time is discovered in the consciousness of shame and is concealed in the shame itself. Shame does not have the structure of consciousness and clarity. It is oriented in the inverse direction; its subject is exterior to me (ibid).

In both cases, access to such inference of disapproval requires the willingness (volition) to engage in an epistemic exercise that takes into account the significance of encountering a third-party perspective. And in both cases, it is the inference of possible disapproval that triggers and frames an ethical deliberation on the part of the subject.

Caveat: Subjectivity and the Impartial Other

From the scholarship that has been cultivated around Smith’s and Lévinas’ projects, an important caveat emerges: It should be kept in mind that the impartial Other is formed and informed by upbringing, culture and social pressure (McCloskey 2008, p. 52).Footnote 1 That is, any mental effort to conjure an external “objective” source of ethical intuition or speculation is inherently subjective. Bauman (1993) observes:

First to delegitimize or ‘bracket away’ moral impulses and emotions, and then to try to reconstruct the edifice of ethics out of arguments carefully cleansed of emotional undertones and set free from all bonds with unprocessed human intimacy, is equivalent (to use the memorable metaphor of Harold Garfinkel) to saying that if we only could get the walls out of the way we would better see what supports the ceiling. It is the primal and primary ‘brute fact’ of moral impulse, moral responsibility, moral intimacy that supplies the stuff from which the morality of human cohabitation is made. After centuries of attempts to prove otherwise, the ‘mystery of morality inside me’ (Kant) once more appears to us impossible to explain away (p. 35).

Bauman goes on to suggest that any effort to step outside ourselves and dispassionately try to understand ethical propositions is doomed to failure. At the end of the day, moral philosophy is an “inside job” that relies upon our own understandings of morality (ibid).

The decision to enter into an intellectual consideration of the ethical implications of a somewhat omniscient third-party perspective may itself be resisted by some. In particular, those who hold a high view of their individual sovereignty may feel threatened by the intrusive God-like implications and demands of the impartial Other. Especially for an atheist like Jean-Paul Sartre, the gaze of the Other is objectifying and dehumanizing: “By virtue of consciousness the Other is for me simultaneously the one who has stolen my being from me and the one who causes ‘there to be’ a being which is my being” (Sartre and Barnes 1992, p. 364). For Sartre, the gaze of God—that is, the gaze of the ultimate “subject who can never be an object”—permanently reduces the human experience to “being-an-object” (ibid, p. 290).

The efficaciousness of bringing forward notions about the nature and implications of the impartial Other, then, is not inherent to any attempt at ethics education or inculcation. Nevertheless, piloting accountants or other professionals through a thought process that takes into account the impartial Other in order to lay a foundation for a critical analysis of ethical issues and implications may be, at best, better than not doing so. A parallel to this may be the critical thinking processes that necessarily accompany any analysis of the ethical aspects of the impartial Other: To expand one’s awareness in the direction of for-the-other (and by doing so to encourage a turn away from a focus on for-itself) necessarily moves the subject in the direction of the ethical (Shearer 2002). At least one classroom study, i.e., that of Sorensen et al. (2015), seems to support this optimism.

The Conceptual Framework and the Promotion of Ethical Sensitivity

Despite their originations in different times and in the context of different philosophical movements, the ethical projects of Smith and Lévinas have some common characteristics. Among these is a concern about ethical sensitivity, that is, awareness and concern about one’s moral stance, actions, habits or practices as they impact others (Borgerson 2007; Rossouw 1994). Smith in particular advocates an engagement in sympathetic imagination in order to take up the perspective of the impartial spectator and thereby stand outside ourselves and assess our actions, habits and tendencies (Brady 2011). So much so that Smith points to the golden rule as a guiding principle for his promotion of ethical sensitivity:

And hence it is, that to feel much for others and little for ourselves, that to restrain our selfish, and to indulge our benevolent affections, constitutes the perfection of human nature; and can alone produce among mankind that harmony of sentiments and passions in which consists their whole grace and propriety. As to love our neighbour as we love ourselves is the great law of Christianity, so it is the great precept of nature to love ourselves only as we love our neighbour, or what comes to the same thing, as our neighbour is capable of loving us (Smith 1976, p. 5).

Lévinas’ project, similarly, is focused on a phenomenology of the sensible:

Sensibility establishes a relation with a pure quality without support, with the element. Sensibility is enjoyment. The sensitive being, the body, concretizes this way of being, which consists in finding a condition in what, in other respects, can appear as an object of thought, as simply constituted (1969, p. 136).

As Shearer (2002, p. 566) notes, Lévinas’ concept of ethics is derived from a sensitivity to the suffering of others that has its origins in the passivity of suffering and the essential for-the-other that is the beginning and source of being. Lévinas (1969) considers the phenomenology of the face—or such intersubjectivities as the gaze, the caress or sexuality—in terms of their radical otherness and the implications they present for grasping the infinite of the Other:

The face resists possession, resists my powers. In its epiphany, in expression, the sensible, still graspable, turns into total resistance to the grasp…The expression the face introduces into the world does not defy the feebleness of my powers, but my ability for power. The face, still a thing among things, breaks through the form that nevertheless delimits it. This means concretely: the face speaks to me and thereby invites me to a relation incommensurate with a power exercised, be it enjoyment or knowledge. And yet this new dimension opens in the sensible appearance of the face (pp. 196–197).

Improving the AICPA Code

Enforcement of the (Entire) Code

As noted above, the AICPA bylaws allow for partial enforcement of its Code. AICPA members are held to standards of conduct that comply with the Code’s rules, but not its principles. By contrast, the IFAC COE requires adherence to both principles and rules. The change would arguably bring the AICPA into greater compliance with its own commitment to “not apply less stringent standards” than those stated in the COE (IESBA 2016, p. 7).

Although the empirical literature on the effect of ethical codes of behavior has shown mixed results (McKinney et al. 2010), the extent to which these codes are actually enforced, rather than merely promoted as part of an image management campaign, largely determines their effectiveness (Rogers et al. 2005). However, determining the effectiveness of the ethical principles of the conceptual framework of the AICPA Code will be difficult, because adherence to both the Code’s rules and principles is currently not mandated. Preston et al. (1995) succinctly described the relationship between the AICPA’s nonbinding statement of principles and its mandatory rules as follows:

[B]y adopting legalistic rules the profession did not entirely surrender its moral elements, but these were relegated to the principles section. Whereas the principles are what the professional accountant must aspire to, it is the rules that he or she must obey (p. 527).

By not mandating adherence to the entire Code (including its principles), the AICPA runs the risk of appearing to lack commitment in its efforts to augment its ethical legitimacy and could also be viewed as having a less-than-sincere commitment to professional ethics. (Long and Driscoll 2008; Gilley et al. 2010). Dillard and Yuthas (2002) concluded that emphasis of the oversight of adherence to rules of conduct portends “the separation of the person from the responsibility of moral behavior” (p. 51). This separation results in a “decoupling of ethical values and norms from articulated codes and rules” which, in turn, leads to a “reduction in personal responsibility and ethical awareness resulting in antiseptic algorithmic rationalizations of behavior” (p. 60). They claim that the attempt to achieve ethical decision making and behavior through such a rules-based regime “has had the effect of obstructing self reflection and allows the abdication of personal responsibility for the consequences of one’s actions” (p. 61).

Other researchers have made similar observations, concluding that a reliance on rules fosters a compliance mindset (Herron and Gilbertson 2004), such that a focus on loopholes is encouraged (Cowton 2009):

Deterrence of unethical or illegal behavior is the primary purpose of most codes of ethics, which is clear from their legalistic/compliance orientation. This is primarily an issue of ‘prevention’ (Gilley et al. 2010, p. 33).

In other words, there is sometimes a human tendency to pay very close attention to the rules and to gravitate toward the edges of the rules without actually violating them. As can occur in the legal profession (Hamilton 2008, p. 116; Rostain 1998, p. 1335), accounting practitioners who apply this technique to their compliance with the Code may find their professional ethics collapsing into a pragmatic calculus of self-interest and self-advantage. Heath (2007, p. 366) defines such gaming of the rules by stating that this dynamic “involves taking actions that are technically not prohibited, but are not intended to be permissible strategies. Such actions violate the spirit, rather than the letter, of the rules.”

But, if the AICPA were to update its bylaws to mandate compliance with the entire Code, rather than only the Code’s rules of conduct, the AICPA’s commitment to professional ethics would be more obvious and more compelling. By mandating adherence to the entire Code, the current protocols for enforcement of rules would not change. Instead, it would make it possible to consider those cases (however few and far between) wherein a member has not actually violated a particular rule of conduct, but nevertheless refuses to consider and implement safeguards to obvious rule violation threats. By opening up the disciplinary process to this possibility, the AICPA would be signaling to its members that the conceptual framework is more than a body of suggestions and talking points.

Peer Review of Conceptual Framework Implementation

One method the AICPA uses to ensure reliable accountability in the USA is its peer review program. Even though the AICPA peer review program has received mixed reviews over the years (Anantharaman 2012, p. 55), peer review under the auspices of the AICPA has evolved from an essentially educational and remedial program to a process that has been characterized by more rigor, enforceability and transparency than in prior decades (Bunting 2004). And yet, the only interaction of the AICPA peer review program with professional ethics is in connection with reviewing the elements of a firm’s quality control system, which includes adherence by the firm to ethical requirements, such as independence, integrity and objectivity.

All firms that perform attestations (audits, reviews and certain compilations) and whose services go beyond those audits of public corporations (that is, those audits covered by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board [PCAOB] inspection system) are required to be reviewed periodically by peer accounting firms. This includes accounting and auditing practices of firms that are not subject to oversight by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), but that are registered with and inspected by the PCAOB.

Peer reviewers examine and analyze various evidential materials including, but not limited to: selected administrative or personnel files, correspondence files documenting consultations on technical or ethical questions, files evidencing compliance with human resource requirements and the firm’s technical reference sources (AICPA 2009). The firms under review are expected to take appropriate actions in response to findings, deficiencies and significant deficiencies identified with their system of quality control or their compliance with the system, or both. Separately, as part of its engagement reviews, the reviewed firms are also expected to take appropriate actions in response to findings, deficiencies and significant deficiencies identified in engagements.

Peer review does not apply to accountants employed by organizations other than public accounting firms that perform attestations, but it covers a critical segment of the profession. Most of the rules (and many of the lengthier interpretations thereof) pertain to member accountants in public practice rather than to those members employed by for-profit companies and other organizations. Similarly, most ethics investigations and disciplinary actions involve members in public practice rather than individuals employed by business or other organizations (Fisher et al. 2001).

Disciplinary actions include those that can result in the termination of a firm’s enrollment in the AICPA peer review program and the subsequent loss of membership in the AICPA and some state CPA societies, and are imposed as a result of failures to cooperate, failures to correct inadequacies, or when a firm is found to be so seriously deficient in its performance that education and remedial corrective actions are not adequate (AICPA 2009).

As stated above, peer reviews involve, in part, obtaining an understanding of the reviewed firm’s quality control system with respect to each of the quality control elements in the AICPA’s Statements on Quality Control Standards (SQCSs) No. 8 (Nagy 2014; AICPA 2012). SQCS No. 8 requires every CPA firm, regardless of its size, to have a quality control system for its accounting and auditing practice. This quality control system should encompass, among other elements, leadership responsibilities for quality within the accounting firm (the “tone at the top”) and adherence to relevant ethical requirements such as independence, integrity and objectivity. The system should also include policies and procedures designed to provide the firm with reasonable assurance that its personnel have the appropriate competence, capabilities and commitment to ethical principles. CPA firms can receive a rating of pass, pass with deficiencies or fail. When peer reviewers discover that a CPA firm is deficient in areas such as relevant ethical requirements, the deficiency becomes part of the review report and must be resolved by the CPA firm as part of the completion of the peer review process. The AICPA peer review program experiences approximately a dozen ethics-related deficiencies per year (AICPA 2015d; Moriarity 2000).

Related SQCS No. 8 elements include: (a) acceptance and continuance of client relationships and specific engagements; (b) human resources and engagement performance and monitoring; and (c) documentation of threats and safeguards applied when threats to independence are not at an acceptable level. For example, reviewers are required to select a sample of acceptance and continuance decisions made by the accounting firm under review, and to determine through examination and analysis of the appropriate documentation whether the firm under review is complying with its policies and procedures and with the requirements of professional standards, including communication with prior auditors, an evaluation of management’s integrity and a determination of whether the firm had the required knowledge and expertise to perform the engagement (AICPA 2009). In other words, because currently the only interaction of the AICPA’s peer review program with professional ethics is either in connection with quality control systems or as a part of independence considerations, peer reviews only take into account a narrow subset of ethics-related systems and processes that are in place, or ought to be in place, at the reviewed firms. Also for firms engaged in auditing public entities, there are few direct and indirect assessments of ethics embedded in the oversight conducted by the PCAOB and the SEC.

The review of psychology studies of professional behavior by Falk et al. (1999) points to factors other than codes of conduct, such as ongoing personal moral development and the fostering of an ethical culture within professional work environments, as having at least as much influence on ethical behavior. The AICPA’s peer review process would be more effective in promoting an ethos of ethical behavior if it included a broader and more rigorous review of threats and safeguards as set forth in the conceptual framework recently added to the AICPA’s Code. By adding this focus to the existing peer review process, the AICPA would also be encouraging and motivating its members toward the development of a habitually stronger and more reliable awareness of potential threats to rule violations, thereby effectively promoting and enforcing a virtue ethic along with its current compliance ethic.

Improvement of Conceptual Framework Guidance

The AICPA’s conceptual framework fosters movement away from noncompliance, but toward what? The AICPA’s Code and related pronouncements do not hold out the described safeguards in terms of movement toward best practices, principled ethics or virtues. The primary ethical sensitivity fostered by the conceptual framework, then, is sensitivity to potential rule violations. Accountants are not redirected toward optimal best practices as much as they are directed away from noncompliance. And yet, movement away from noncompliance infers movement toward something. The safeguards recommended by the AICPA are comprised of small steps that focus on ethical risk avoidance. Larger notions of principled best practices or virtues are not encompassed by the limited scope of the recommended safeguards. The promulgation of the AICPA’s new conceptual framework without an overt promotion of such virtues appears to be a missed opportunity.

An example from the AICPA Conceptual Framework Toolkit for Members in Business (AICPA 2015a, p. 7) demonstrates this missed opportunity. The example describes an accountant who works as a CFO. The facts are described as follows:

A member is the CFO of a closely held company. The owner’s nephew just graduated with an accounting degree and has no prior experience working in an accounting role. The owner is pressuring the member to hire his nephew as the controller.

The Toolkit describes the accountant’s analysis of this situation in light of the Code and the accountant’s conclusion that the circumstances create a significant risk of noncompliance with the Code’s rule against subordinating one’s judgment (contained within a general standards rule of the Code). The risk arises from the undue influence being exerted by the owner’s efforts to pressure the CFO into hiring the owner’s nephew as the controller. The Toolkit suggests that a possible safeguard against violating the subordination of judgment rule would be for the accountant to consider putting controls in place in order to allow the CFO to closely supervise and review the nephew’s work while training the nephew.

The AICPA’s analysis of this hypothetical case is deficient in two ways: First, there is no reference to the thought process that would lead the CFO to conclude that the described situation poses a substantial risk. The conceptual framework calls for an analysis that takes into account the likely expectations of a reasonable and informed third party who is aware of the relevant information as compromising their compliance with the rules. Instead of referring to a thought process to determine whether a situation is or is not a substantial risk, the Toolkit merely advises readers to “identify the threats that you believe exist and describe why you believe they exist” (AICPA 2015a, b, p. 11). Similarly, once those threats are identified, Toolkit readers are instructed to describe why they believe the threats they have identified are or are not significant (ibid). No mention is made about considering the possible expectations of an impartial and informed third party.

Second, there is no mention of or attention paid to the ethical principle(s) in play. To identify and safeguard a risk of noncompliance (i.e., a risk of violating the rule against subordination of judgment) is to address one terminus of the dynamic. Moving away from a rule violation is an important and significant dynamic, but toward what? This hypothetical case provides an opportunity to show a movement toward the principle of objectivity, but this is not mentioned or addressed in the AICPA analysis of this case.

An example from the AICPA Conceptual Framework Toolkit for Members in Public Practice (AICPA 2015b, p. 7) is similarly deficient. In this example:

A partner’s nondependent son is a full-time broker and earned a significant commission for securing a prime rental property for a large local retailer. The retailer has now contacted the partner’s firm to ask if the firm would perform its year-end financial statement audit.

As in the previous example, the dilemma is resolved without any reference to the likely perceptions of an uninterested third party and without any reference to the ethical principles that might inform such a situation. No mention is made of such principles as trustworthiness, objectivity or the requirement to foster the appearance of independence. As it happens, the AICPA’s guidance documentation concludes that not only is there no significant threat to noncompliance with any rule, but that there is no threat at all.

None of the other hypothetical examples in the AICPA Toolkit for Members in Business (AICPA 2015a) or in the Toolkit for Members in Public Practice (AICPA 2015b), and none of the examples in a similar guidance document pertaining to independence (AICPA 2015c), provide insight into the intellectual exercise of consulting a third-party perspective; none of the guidance points to the principles that inform the impetus away from potential rule violations. While it might not be necessary for the AICPA to delve into the kind of in-depth theoretical foundations as demonstrated here in regard to the work of Adam Smith and Emmanuel Lévinas, we believe that some effort to explain and elaborate on the efficaciousness of the impartial observer protocol elevates the perceived relevance, utility and potential impact of the conceptual framework.

As long as the Code remains focused on rules, the AICPA’s organizational efforts to encourage greater ethical sensitivity by its promulgation of its conceptual framework will necessarily have less than optimal results. Noncompliance–avoidance, supported by a procedural regime that requires accountants to consider and attend to the likely observations and expectations of a third-party observer, is a start that, as we have shown, has some basis in ethical theory. However, by downplaying this epistemic exercise in its guidance documentation and examples, and by giving no attention to the role of its organizational ethical principles, the AICPA is, we believe, foregoing opportunities that would enhance ethical sensitivity.

Conclusion

The AICPA’s Code has been the object of studied criticism in recent years, largely in regard to its rules-based compliance strategy. The addition of the conceptual framework provides an, as yet, unrealized opportunity to bring more focus to principles. Behavioral dynamics that represent a move away from single-minded focus on rule violations are enhanced when they are simultaneously directed toward ethical principles and when they are made more compelling as a result of organization commitment and enforcement. Efforts to promote patterns of ethical practices or virtues would be strengthened both when noncompliance with rules is proscribed and adherence to principles is prescribed.

The AICPA’s newly adopted conceptual framework is the beginning of a turn away from an exclusively rules-based professional ethics regime and arguably toward a structure that is more attentive to principles. The conceptual framework emphasizes and encourages a greater sensitivity to the risks of potential noncompliance with rules. This dynamic would be more robust and more compelling if the AICPA also attended to the accountant’s corresponding turn toward the sensitivity to, and the embrace of, core professional ethics principles.

To complete this task, the AICPA would need to broaden its organizational commitment to its Code (and fulfill its obligations to conform its Code to the IFAC’s minimum standards) by ensuring that its principles have authoritative parity with its rules. The project would also be well served if more robust guidance was provided in regard to the epistemic exercise involving the “reasonable and informed third party,” and if the AICPA’s peer review process incorporated oversight of the implementation of the conceptual framework.

The AICPA is one of many organizations wrestling with the dynamics of professional ethics rules and principles. This tension is reflected in recent changes to the codes of ethics of other accounting organizations as well as the codes adopted by other professions. As Preston et al. (1995) asserted, a “persistent self-improvement and examination is the means by which an ethical subject is constantly being re-created” (p. 521). This requires what Gendron et al. (2006, p. 170) refer to as ethical commitment, that is, an intentional “adherence to ideal moral values” and a willingness to enforce such values within the professional community. Dobson and Armstrong (1995) suggest that the pursuit of personal excellence “is only possible within a polis: a community that nurtures such pursuit” (p. 199). This paper has treated the AICPA’s recent promulgation of a conceptual framework as a case study that provides the opportunity to participate in the nurturing of this pursuit.

Notes

From this point, we will use the term “impartial Other” as an inclusive reference to both Smith’s impartial spectator and Lévinas’ Other.

Abbreviations

- AICPA:

-

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

- Code:

-

AICPA Code of Professional Conduct

- CFO:

-

Chief financial officer

- COE :

-

Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants (IESBA)

- CPA:

-

Certified public accountant

- FASB:

-

Financial Accounting Standards Board (USA)

- GAAS:

-

Generally Accepted Auditing Standards

- GAAP:

-

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

- IESBA:

-

International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants

- IFAC:

-

International Federation of Accountants

- IFRS:

-

International Financial Reporting Standards

- IRS:

-

Internal Revenue Service (USA)

- PCAOB:

-

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (USA)

- SEC:

-

Securities and Exchange Commission (USA)

- SQCS No. 8:

-

AICPA Statements on Quality Control Standards No. 8

- TMS :

-

Theory of Moral Sentiments

References

AICPA. (1972). Restatement of the Code of Professional Conduct: Concepts of professional ethics, rules of conduct; interpretations of rules of conduct. Retrieved December 15, 2016, from http://clio.lib.olemiss.edu/cdm/ref/collection/aicpa/id/65782

AICPA. (1988). “7.4 Disciplining of Member by Trial Board” in AICPA Bylaws and implementing resolutions of council. Retrieved December 15, 2016, from http://www.aicpa.org/About/Governance/Bylaws/Pages/bl_740.aspx

AICPA. (2009). AICPA standards for performing and reporting on peer reviews. Retrieved December 15, 2016, from http://www.aicpa.org/research/standards/peerreview/downloadabledocuments/peerreviewstandards.pdf

AICPA. (2012). QC Section 10: A firm’s system of quality control. Retrieved December 15, 2016, from http://www.aicpa.org/Research/Standards/AuditAttest/DownloadableDocuments/QC-00010.pdf

AICPA. (2013). Code of Code of Professional Conduct and bylaws (as of June 1, 2013). New York: American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Inc.

AICPA. (2015a). Conceptual framework toolkit for members in business. New York: AICPA. Retrieved December 15, 2016, from https://www.aicpa.org/InterestAreas/ProfessionalEthics/Resources/DownloadableDocuments/ToolkitsandAids/ConceptualFrameworkToolkitForMembersInBusiness.docm

AICPA. (2015b). Conceptual framework toolkit for members in public practice. New York: AICPA. Retrieved December 15, 2016, from https://www.aicpa.org/InterestAreas/ProfessionalEthics/Resources/DownloadableDocuments/ToolkitsandAids/ConceptualFrameworkToolkitForMembersInPublicPractice.docm