Abstract

A triad society is a well-established, cohesive branch of Chinese criminal organizations focally aimed at monetary gain. Abiding by the same code of conduct and chain of commands assured the formation of blood brothers with one solitary aspiration. With such authority and manipulation amid the triad syndicate, this aspiration inevitably resulted in the running of illicit activities in triad-controlled territories. As the intimacy between Hong Kong and China grew deeper, an upsurge of cross-border crime has emerged since the 1990s. Prosperity in China caused a process of mainlandization of triad activities because of an ever-increasing demand of licit and illicit services in Chinese communities. Consequently, triad societies have changed from a rigid territorial base and cohesive structure to more reliance on flexible and instrumental social networks. They are entrepreneurially oriented and involved in a wide range of licit and illicit businesses based in Hong Kong but spread to mainland China.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Organize Crime

- Psychotropic Drug

- Transnational Crime

- Independent Commission Against Corruption

- Police Corruption

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

The Chinese triad society, or Hung Mun, was founded in the seventeenth century in China with a strong patriotic doctrine, but since the Second World War it has gradually disintegrated into a number of triad societies operating independently of each other in Hong Kong. They are organized criminal syndicates using triad names to pursue monetary gain. In Hong Kong, it is unlawful for anyone to act as a member of a triad society. It was found that there were 294 active youth gangs in Hong Kong, under the control of 19 triad societiesFootnote 1 (Lo 2002). The three most active triad societies are the 14K, the Sun Yee On, and the Wo Shing Wo (Liu 2001: 57).

This chapter outlines the conventional triad structure and activities and highlights how the triads change in response to the socioeconomic changes in Hong Kong and mainland China. It is argued that because of the stepping up of anti-triad measures in Hong Kong and the growing prosperity in mainland China, a process of mainlandization occurs whereby triad societies are attracted to launch some of their operations in the mainland. Because of this move, structurally they become disorganized and business-wise they become more entrepreneurial.

Conventional Triad Structure and Activities in Hong Kong

Traditionally, triad organized crime was facilitated by an established organizational structure (Fig. 4.1). The chairman of a triad society was known as Shan Chu (secret triad code 489), who was assisted by the Fu Shan Chu (Deputy Chairman, 438) and had the authority to make final decisions in all matters relating to the society. Assisting him were two officers of equal standing, Heung Chu (Incense Master, 438) and Sin Fung (Vanguard, 438), who had seniority in ranking and age. They were responsible for initiation and promotion ceremonies, as well as recruitment and the expansion of the society. At the middle-level were three officers: Hung Kwan (426), Pak Tsz Sin (415), and Cho Hai (432). Hung Kwan in Chinese means ‘red pole’, signifying a weapon used in fighting. This officer is well-trained in Chinese martial art or tough and brave in fighting. He is the leader of fighters during triad warfare and also responsible for inflicting punishment on traitors. Pak Tsz Sin in Chinese means ‘white paper fan’, used by intellectuals in ancient China. This officer is the mastermind of the society and normally appointed from amongst the most intellectual and educated members. He is the society’s advisor, thinker, and planner. Cho Hai in Chinese means ‘straw sandal’, often used by messengers and travelers of ancient time. Being the liaison officer of the society, he becomes the intermediary between the society and its branches. At the bottom of the hierarchy are Sze Kau (49) or ordinary members, who form the majority of the society. Under the Sze Kau, there is a kind of affiliated membership called Hanging the Blue Lantern. The former has undergone a formal initiation ceremony in order to become a triad member, while the latter has not. Both terms are now used to identify triad members of the lowest rank.

Triad subcultural values included loyalty to the gang, righteousness, secrecy, and sworn brotherhood. There were clear rules, rituals, oaths, codes of conduct and chains of command, as well as a central control over the behavior and activities of the triad’s members. Triad norms and control mechanisms directed members in what they should do and not do, thus fostering cohesiveness and unity within the triads. Such structural and subcultural control facilitated the triads in compelling gang members to run illicit activities. Triad members were required to regard themselves as one family and blood brothers; they were expected not to do harm to their brothers even under untoward circumstances and to sacrifice themselves for the triad society (Chin 1990; Lo 1984). Triad members would take revenge if their brothers were attacked by rival gangs.

Territoriality was another key element of triad organized crime. Even today, different triad societies have their own turf or monopolize certain economic sectors, without interfering with one another (Zhao and Li 2010). Clashes and violence occur when rival gangs cross the line and step into their territory. The sense of ‘triad territory’ is reflected in the following case:

On 13 February 2003, at 2 a.m., a leader of the Wo Shing Wo triad, Ying Kit, self-identified as the ‘Tiger of Jordan’, yelled at the patrolling police in front of his followers, “I am in charge of this area after midnight!” He is the first triad member to ever state such a taboo topic in public.

Triad societies have been involved in different forms of violence and street crime in Hong Kong (Chu 2000; Fight Crime Committee 1986; Leong 2002). Broadhurst and Lee (2009) summarize them as follows:

Typical triad-related offences in HK include blackmail, extortion, price fixing, and protection rackets involving local shops, small businesses, restaurants, hawkers, construction sites, recycling, unofficial taxi stands, car valet services, columbaria, wholesale and retail markets and places of public entertainment such as bars, brothels, billiard halls, mahjong gaming, karaoke, and nightclubs (….) Triads often engage in street-level narcotic trafficking, or operate illegal casinos, football gambling and loan sharking (….) Prostitution, counterfeit products, pornography, and cigarette and fuel smuggling are also important sources of street-level illicit profit for triad societies (Broadhurst and Lee 2009: 14–15).

In addition to conventional criminal activities, some triad societies also engage in legitimate businesses. For instance, they “monopolized the control of home decoration companies, elements of the film industry, waste disposal, and non-franchised public transport routes” (Broadhurst and Lee 2009: 14–15).

Triad Activities in the Era of Political Transition and Economic Convergence

Hong Kong was a British colony between 1842 and 1997. Britain handed Hong Kong back to China as a special administrative region on 1 July 1997. The Sino-British Joint Declaration guaranteed that Hong Kong would maintain high-level autonomy and retain its capitalist system for 50 years under the model of ‘one country, two systems’. China’s resumption of the exercise of sovereignty over Hong Kong not only changed Hong Kong’s political and social life but also produced significant changes in the social order of Hong Kong.

The Issue of 1997 and the Triad Exodus

Before the handover, there was concern about a triad exodus to the West and an expectation that they would expand their activities overseas for fear of a communist takeover. The issue of 1997 worried people from all walks of life. Some wealthy criminals headed for Australia and North America by means of investment, at the time a general trend in Hong Kong society. Like many respectable citizens, some triad gangsters migrated to obtain a foreign passport as an insurance against communist rule. But this by no means implied that they would give up their criminal career. Their money-making drive remained the same. Whenever and wherever there were opportunities to make money, they would seize them, whether it was in Toronto, New York, London, Sydney, Shanghai, or Hong Kong. The positions of triad members who settled down abroad were taken over by their followers or other triad gangs. Due to the increase in legal and illegal business opportunities in mainland China, the expected triad exodus from Hong Kong to the West never happened (Lo 1995; Zhao and Li 2010). Rather, the prosperity of Hong Kong and the surrounding region increased the demand for licit and illicit services provided by the triads, such as the entertainment business and the smuggling of scarce goods.

Cross-Border Crime

Since China began its economic reform in the 1980s, smuggling goods to mainland China, from cell phones, automobiles, electrical appliances to industrial diesel oil, had become a blooming business. Following the growing integration between Hong Kong and the mainland, the 1990s were characterized by the rise of cross-border crime. High-speed vessels containing smuggled goods crossed the sea between Hong Kong and the Chinese border (Lo 1992). Attempting to capitalize on the booming China business market, the triads further forged cooperative relationships with mainland criminal groups. Gangsters from southern China were employed by Hong Kong triads to commit crimes across the border, ranging from contract killings to armed robbery (Liu 2001). Hong Kong triads also invested in the entertainment business in southern China and simultaneously collaborated with local gangs in illegal activities such as drug trafficking (Laidler et al. 2000). Triad societies increasingly invested in legitimate businesses and teamed up with entrepreneurs to monopolize the newly developed Chinese market (Chu 2000, 2005; Lintner 2004). The cheaper vice services and drugs available in Southern China attracted Hong Kong customers to use these services across the border.

In the old days, triad gang wars usually involved only chopping weapons and seldom harmed innocent people. With the rise of cross-border crime, Molotov cocktails were used to fight for triad territories; AK47 machine guns and grenades were used in armed robberies of banks and goldsmith shops in broad daylight. Robbers traded shots with the police with their powerful weapons and turned the busy streets into temporary battlefields. Notorious violent criminals and robberies plagued the early 1990s. It was believed that members of the Big Circle Gang and Hunan Gang (gangsters with China connections and military training) were involved in these violent crimes.Footnote 2 They committed crimes in Hong Kong and hid themselves in Southern China, thus making police investigation difficult.

On the other hand, due to political, cultural, and legal differences, the colonial Hong Kong government had no formal agreement with mainland China in handling criminals. Before starting up the semi-official cooperation to combat cross-border crime in 1985,Footnote 3 Hong Kong constantly rejected rendition requests from the mainland, because returning criminals to China would “violate Hong Kong’s domestic commitment to the rule of law and international obligations under human rights treaties” (Wong 2004: 21). Because of the lack of close cooperation between the two jurisdictions and the absence of the death penalty in Hong Kong, Hong Kong became a safe haven for fugitives who escaped justice from mainland China. Very little could be done by the mainland police if the criminals hid in Hong Kong (Wong 2004).

The 1997 handover enabled much closer communication and more collaboration between the provincial governments of Southern China and the Hong Kong special administrative region government. The situation is very much different from the era of British rule in Hong Kong. Today, both Hong Kong and mainland China are no longer favorable hiding grounds for absconding criminals, and violent cross-border robberies were rarely seen in the 2000s.

Patriotic Triads

On 31 March 1992, the Minister of Public Security of China, Tao Siju, remarked that some triad members were patriots. Since then, some influential Hong Kong triad leaders were absorbed by the Chinese government through its united front tactic (Lo 2010) for three main reasons. First, it was to avoid disturbing Hong Kong’s law and order and to ensure social stability before and after the transfer of sovereignty. Second, the triads would not be further involved in pro-democratic activities in China, such as the Yellow Bird Action, where over 100 pro-democracy student leaders were smuggled out of China by triad members after the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989. Third, the existence of powerful triad friends in Hong Kong was obviously to China’s advantage because it would bar the infiltration of Taiwanese gangs into Hong Kong to join forces with anti-Beijing liberals or to influence local elections as they did in TaiwanFootnote 4 (Chin 2003). Thus, rather than suppress triad activities, the triad leaders were conferred a ‘patriotic triad’ label by Chinese leaders. This indirectly facilitated them to establish guanxi with officials and state enterprises and enabled them to locate and gain access to licit and illicit business opportunities in the mainland (Broadhurst and Lee 2009; Lo 2010). Guanxi is defined in China as the “personal relationship and reciprocal obligation developed through a particular social network” (Lo 2010: 853) Williams and Godson suggest that guanxi relationships “provide a basis for the global activities of Chinese criminals” (2002: 330).

Regulations of Triad Activities in Hong Kong

Combating Police Corruption in the 1970s

Before the 1980s, triad activities were fostered by rampant police corruption. The most salient feature of syndicated police corruption was the existence of an informal hierarchy with middle-ranking Chinese officers—usually the detective staff sergeant—acting as the leader. These officers collaborated closely with triad syndicates to govern the criminal world (Cheung and Lau 1981; Lo 1993). As a notorious drug syndicate boss confessed in court, “law did exist: police enforcing it did not…my money did” (Hong Kong Law Report 1984, II: 282). In 1973, the escape of an expatriate Police Chief Superintendent who was under investigation for corruption, elicited mass public outcry and demonstrations by university students and young people. As a positive response, the government established the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) in 1974. The ICAC made their primary aim the elimination of corruption syndicates in government departments, especially the police force (Lo 1993). On 28 October 1977, two thousand policemen held a mass assembly and marched to the Police Headquarters to present a petition. Industrial action by policemen was proposed, threatening law and order. The Governor responded by issuing an amnesty which fulfilled two functions. First, it signified a cut-off line, an ultimatum. The pardon gave the police only one chance. Second, the limited human resources of the ICAC could be focused on the present situation instead of the past, and thus corruption was no longer a low-risk crime (Lo 1993). In the following years, statistics show that police corruption dropped sharply and syndicated corruption disappeared. Without this protective umbrella, the triads had to rely on their own network and their power had been substantially weakened.

Triad Renunciation Scheme

The government continued to tackle triad activities by introducing the Triad Renunciation Scheme (TRS). A Triad Renunciation Tribunal, independent of government departments and directly reporting to the Governor, was established in 1988. TRS was part of an anti-triad package that attempted to reduce the soaring number of triad activities in the 1970–1980s. Under the Societies Ordinance, a person who had joined a triad society was liable to prosecution whether or not he remained an active triad member, hence the adage ‘once a triad, always a triad’. The Ordinance was amended so that those who were, or believed themselves to be, triad members were allowed to renounce their triad membership. Having renounced, they would be free from prosecution for offences relating to triad membership that predated the renunciation. After 5 years from the date of renunciation, legal proceedings for these offences would lapse and the renouncer would be left with a clean record in respect of these offences.

Under the TRS, triad members had to self-disclose their triad connections to the tribunal. The act of reporting to the authorities of one’s triad connection is regarded as a serious breach of triad norms governing loyalty and brotherhood, thus deserving the most serious punishment. This deterred the participation of members of active triad societies (Broadhurst and Lee 2009). Thus, the TRS was criticized as ineffective as it failed to address the underlying structure and subculture of triad societies, and consequently, it ended in failure (Huque 1994).Footnote 5

The Organized and Serious Crime Ordinance and Other Related Ordinances

Later, another new legislation, the Drug Trafficking Ordinance 1989, was introduced to control triad organized crime. Due to the complexity of the law and its failure to address the structure of triad organized crime, it tended to target the perpetrators of the crime instead of triad controllers or leaders. As such, it was criticized as ineffective in reclaiming and targeting the wealth of the triads (Broadhurst and Lee 2009). In responding to the problems with existing legislation, the government enhanced police and prosecution powers by the enactment of the Organized and Serious Crime Ordinance (OSCO) in 1994. As a powerful legislative tool to tackle the triads, it enhanced police capability with new powers of investigation and greater control over the proceeds of crime. Its essence was “to redefine organized crime offences, target the wealth of criminals and the means to launder illegal proceeds, to enhance penalties and to prepare the ground for production of evidentiary materials, orders and witness orders” (Broadhurst and Lee 2009: 30).

Before the introduction of OSCO, there was only one piece of legislation defining and governing triad organization and activities, i.e. the Societies Ordinance. According to Section 18 (3) of the Societies Ordinance, every society which uses any triad ritual or which adopts or makes use of any triad title or nomenclature shall be deemed to be a triad society. In addition, other specified offences relating to triad membership are outlined in Sections 19 and 20 of the Societies Ordinance: being an office-bearer or claiming to be an office-bearer of an unlawful society; acting as a member of an unlawful society, or attending a meeting of or paying money to an unlawful society; being a member of a Triad Society, claiming to be a member of a Triad Society, attending a meeting of a Triad Society or possessing any books or accounts, writing, lists of members, seals, banners or insignia of any Triad Society. Although the ordinance does not specify what rituals constitute triad membership, Section 39 of the ordinance gives the magistrate or judge the right to refer for the purpose of evidence to “The Triad Society or Heaven and Earth Association” by William Stanton and to any other published books or articles on the subject of unlawful societies which the magistrate may consider to be of authority to determine if the accused is a triad member. Triad expert testimony is also commonly used in court for determining triad membership.

The OSCO has resulted in substantial changes in the use of evidentiary materials. According to Section 2 of the OSCO, organized crime is defined as any activity connected with the activities of a particular triad society; activity related to the activities of two or more persons associated together solely or partly for the purpose of committing two or more acts, each of which is a Schedule 1 offence and involves substantial planning and organization; or any activity that is committed by two or more persons, which involves substantial planning and organization and involves loss of life, serious bodily or psychological harm, or serious loss of liberty of any person. The offences listed in Schedule 1 of the Ordinance include murder, kidnapping, and other statutory offences related to firearms, drugs, smuggling, counterfeiting, and gambling.

Instead of emphasizing the rituals and titles of conventional triads, the OSCO redefines organized crime groups as any group of two or more persons associated solely or partly for the purpose of engaging repeatedly in offences. The redefinition broadens the range of organized crime subject to the extended investigation powers, and allows for easier identification of triads with a view to investigation and prosecution. The introduction of civil forfeiture regimes for the recovery of criminal proceeds in OSCO not only helps to curb the wealth and income generated from organized crime, but also helps to combat money laundering by the triads.

Furthermore, two other ordinances were enacted in the 2000s. The Interception of Communications and Surveillance Ordinance, enacted in 2006, enhanced the investigative powers of law enforcement agencies by allowing the use of regulated telecommunications interception to investigate crime networks, which increased the level of risk for triads and criminal syndicates. The Witness Protection Ordinance was enacted in 2000. Both pieces of legislation further strengthened the surveillance power of OSCO in controlling triad activities and facilitating law enforcement agencies to produce evidentiary materials for successful prosecution. Before the enactment of OSCO, most law enforcement resources were directed at tackling the hierarchical structure and subculture of triad societies, but this hindered them from effectively dealing with triad societies as criminal enterprises (Broadhurst and Lee 2009). The OSCO allows them to refocus their limited resources and target the changing nature of triad organized crime.

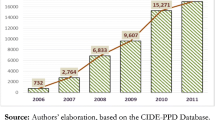

Since the formation of the ICAC in 1974, the introduction of anti-triad regulations, and the empowerment of law enforcement agencies in the 1980–1990s, triad activities have continued to drop (see Fig. 4.2). The triads were forced to move their business away from conventional triad crime to the less regulated illegitimate market; run quasi-legitimate businesses within the legal gray area; reform their street crime operations to business enterprises; and move their operations to neighboring regions or overseas countries (Lintner 2004; Liu 2001). These changes will be discussed below.

Reports of triad society ordinance offences (Rate per 100,000 population 1968–2008). Source RHKP Annual Reports 1968–1997 and HKP Police Review 1998–2008, cited from Broadhurst and Lee (2009: 17)

Socioeconomic and Legal Environment in Mainland China

China’s Rapid Economic Growth

The GDP in China has been steadily rising since 1996. It has quadrupled from around 70,000 million yuan in 1996 to around 300,000 million yuan in 2008. Among other things, China is the biggest consumer of energy products. According to the World Bank, China accounted for half of the global growth in metals demand, and one-third global growth in oil demand in 2004, and became the world’s largest auto market in 2009. China contributed to one-third of the global economic growth in 2004 and achieved 14% of the world economy on purchasing power parity basis in 2005 (second only to the United States). Foreign exchange reserves exceeded $1,000 billion (exceeding Japan), and are growing at about $200 billion a year. The GDP per capita in China rose from 119 yuan in 1952 to 16,084 yuan in 2006. It skyrocketed in the last decade, with a GDP per capita in 2006 double that of 5 years earlier. Compared with other nations around the world, China is the fastest-growing economy in terms of GDP accumulated growth. The above data show that China is catching up as one of the world’s largest economies.

The economic prosperity of China is also reflected in its stock markets. Since 2002, both total market capitalization and total stock turnover have been rising. The former rose more than three times from 3,832,900 million yuan in 2002 to 12,133,600 million yuan in 2008. The total turnover increased almost six times from 2,799,000 million yuan in 2002 to 16,711,300 million yuan in 2008 (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2010). The structural changes in the Chinese stock markets, such as a jump in listings and the allowance of short sales in 2010, have boosted stock trading and market fluctuation. As the triads will go where the money lies, they will be attracted to the flourishing economy of China.

Corruptibility of Officials

Corruption is rampant in mainland China (Lo 1993; Jiang 2008). It is a major contributor to the growth of a black economy and the persistence of criminal activities. As Harris (2003: 90–91) observes about the notorious Yuanhau case in Xiamen: “wherever else the black economy became mainstream, and virtually all the city’s most senior officials were working against the interests of Party, Province and Beijing (…) corruption and smuggling, though ultimately destructive, in the short term fuel the local economy.” Transparency International publishes an annual Corruption Perceptions Index which ranks nations in terms of the degree to which corruption is perceived to exist among politicians and public officials. Over the last decade, China’s score remained below 4.Footnote 6 In 2009, China was ranked 79th with a score of 3.6, suggesting that corruption has not been under control. Once government officials and law enforcement officers are corruptible, the risk for being arrested and sentenced is low for the triads.

A Lack of the Rule of Law

A rule of law society does not allow individual or political goals to be placed above the law, thereby minimizing the human element, arbitrariness, or manipulation during law enforcement and criminal justice processes. These conditions are not always met in China. Many unique concepts, such as ‘rule by the people’, ‘absence of the presumption of innocence’, ‘leniency for self-confession, severity for resistance’, and ‘toeing the Party line’, prevail in the Chinese criminal justice system (Lo 2011). The exertion of external influence and pressure, the unpredictability of court decisions, and the violation of human rights in law enforcement put China in a state characterized by the ‘rule by person’ or, at most, the ‘rule by law’, rather than the ‘rule of law’ (Jiang 2008). The rule by law fosters selective targeting, patronage, scapegoating, politically driven agendas, and inconsistent law enforcement. A judicial system that toes the Communist Party line further offers unreasonable or disproportionate punishment and sanctions in the fight against crime. Because of weak external control, those in power are able to distort the legal process to preserve their own interests. Against this background, the triads can make use of these loopholes to benefit from their guanxi with those in positions of power.

Protective Umbrellas

It has been suggested that there are ‘protective umbrellas’ in China (Zhang and Chin 2008) which means that criminal syndicates connect with officials through the offer of a range of interests, such as luxurious gifts, overseas travel, clearing of gambling debts, sex services, or simple bribery, in exchange for protection in legal and illegal business activities. Because of the absence of the rule of law and the prevalence of guanxi and corruption, protective umbrellas have developed rapidly alongside China’s booming economy (Zhao and Li 2010). Thus, Article 294 of the Criminal Law of China stipulates that government officials offering protection to triads or allowing triads to commit illegal activities will be sentenced to 3 years' imprisonment, and in serious cases, 3–10 years imprisonment. This move by the Chinese government confirms the existence of protective umbrellas in the mainland.

Changing Triad Activities in the New Millennium

In the 2000s, the convergence between Hong Kong and mainland China sparked off close collaborations between criminals and businessmen in both territories, as well as in other jurisdictions. Many triads formed alliances with local syndicates and other ethnic criminal groups in the trafficking and distribution of narcotics in Australia, the U.K., the United States, and Canada. Investments in legitimate business enterprises for the purpose of laundering money are common practice in North America and Southeast Asia (Curtis et al. 2003). In the following, selected examples of changes in the activities of triad organized crime are outlined.

Triad Involvement in Transnational Organized Crime

A US Congress report in 2003 disclosed that some triads, in particular the 14k and the Sun Yee On, were actively involved in the domestic drug market and the import and re-export of narcotics in countries such as the Netherlands, Canada, Thailand, the Philippines, and South Africa (Curtis et al. 2003). For instance, in the Netherlands, Hong Kong triads were in “full control” of importing heroin from China and Southeast Asia. They were also involved in the domestic sale of heroin and used the Netherlands as a transit point for smuggling heroin to other parts of Europe (Curtis et al. 2003: 10–11). In South Africa, the Sun Yee On group competed with other ethnic groups to dominate the importation of methaqualone (Curtis et al. 2003: 36). In Thailand, Hong Kong triads were known to be in charge of the trafficking of heroin and other types of narcotics from Burma to Thailand and their re-export to other countries.

Smuggling women for prostitution is a transnational crime in which triads are commonly involved. According to the US Congress report, triads involved in the international sex trade transported women from their countries of origin to destinations in the West via the Philippines. In Thailand, the 14K triad dominated the trafficking of women from China to Bangkok, while the Sun Yee On was well known for utilizing the false and stolen passport market to assist in its transport of prostitutes to Japan in cooperation with the Yakuza (Curtis et al. 2003).

Although the abovementioned US Congress report argued that triads are actively involved in different types of transnational crimes across regions, their findings remain inconclusive, and the role of triads in transnational crime is still unclear. This is partly due to the ambiguous definition of triads, as the term sometimes includes other Chinese criminal syndicates from Mainland China and Taiwan. In addition, the research does not provide detailed evidence to support the level of involvement of the triads in these transnational organized criminal activities.

In contrast, a report by the US National Institute of Justice indicated that the relationship between triads and transnational crime is relatively weak (Finckenauer and Chin 2007). Zhang and Chin (2002, 2003) argued that triad involvement in transnational human smuggling is restricted to the actions of individual triad members. The perpetrators are often individuals from different backgrounds who only share the same money-making goal. They are not bounded by the rigid triad structure or subculture, but team up through informal social networking on a tentative basis (Chin 1999; Zhang 2008; Zhang and Chin 2003).

Prostitution

Prostitution, operated mainly through one-woman brothels, guest houses, and karaoke clubs, used to be a major source of income of Hong Kong triads. The solicitation of customers is confined only to triad-controlled territories where the triads themselves maintain order so as to avoid police intervention. However, in the last decade, Hong Kong triads have faced keen competitions from the cheaper sex services provided by criminal syndicates in Southern China. The 24-hour cross-border passage to China gives Hong Kong residents the convenience to visit nightclubs or brothels in the mainland. Consequently, while triad-run brothels (operated in guest houses) still exist, their business has declined substantially.

Since Chinese nationals are now granted tourist visas more easily than before, Hong Kong has become an entrepôt for prostitutes. The previous model of smuggling women to Hong Kong and abroad begins to diminish. Triad members visit Chinese cities to connect with local criminal groups for the selection of women. Upon arrival in Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, Japan, and Australia, these women are forced to work long hours in brothels, hotels, or guest houses, first to recoup their passage, food and accommodation, and then to earn their ‘wages’. Of course the triads take a large share for the organization and operation. The women are highly disciplined in soliciting customers and providing the service (or have been pre-disciplined by the local gangs before they left mainland China), knowing that they cannot leave the territory or cause any trouble. When their tourist visa expires, another group of women arrives to replace them. Because of the tourist status, short-term stay, and high turnover of the sex workers, both the cost and risk of running such operations are lower than in the old days of human smuggling.

From Heroin to Psychotropic Drugs

In the 1970–1990s, the Hong Kong triads often derived the largest part of their income from the trafficking of drugs. If each recorded drug addict in Hong Kong (about 10,000) consumed 1 g of heroin per day, the sum totals to 10 kg of heroin a day or 3.6 tons of heroin a year, and this is only the basic consumption, excluding money generated from re-exports.

In recent years, the Golden Crescent has become the major source of heroin trafficked into the nearby Xinjiang province of China, and heroin is now mainly locally consumed in Chinese cities and rarely transited to other nations via Hong Kong, as happened in the old days (So 2011). Along with this change in drug consumption in China, the use of heroin has been in sharp decline in Hong Kong. In the 2000s, the triads replaced it with psychotropic drugs such as ice, ecstasy, and ketamine. Ketamine, nicknamed ‘k-tsai’, is now becoming popular in Hong Kong due to its low priceFootnote 7 (especially compared to cocaine and cannabis), convenience of consumption (compared to heroin), and availability to young people. Since ketamine is available in tablet form, amateurs—usually young drug users—are being used as couriers for trafficking (So 2011). The distribution network of ketamine and ecstasy used to be venue based. It started in the local entertainment venues and gradually moved across the border to nightclubs in Southern China. Some youth buy drugs in these nightclubs for personal use and then take the rest back to Hong Kong to sell to their schoolmates. The easy transport of psychotropic drugs not only accelerates the spread of drug use among youngsters and students, but also changes the drug business model from venue or territorially based operations to the sale of drugs through social networks (So 2011).

In order to shift the target market from adults to young people, the drug business has been revitalized and modernized through the adoption of business management concepts such as the introduction of marketing strategies to attract new customers and the innovation of the drug sales networks. Brand building is an important strategy to reach new customer segments. Brand repositioning is accomplished by changing the image of drugs among young people from negative (the stereotype of the emaciated heroin addict) to positive (the sociable and energetic psychotropic drug user). The triads emphasize the positive aspects of psychotropic drug use (such as the slimming effect of drugs to attract female customers) and promote false perceptions such as “psychotropic drugs can generate excitement and help relieve stress”; “psychotropic drugs are not addictive like heroin”; “psychotropic drugs are a gateway to social involvement”; and “taking ketamine is a contemporary and chic way of life”. In addition, the triads also redesign the appearance of ecstasy tablets by using different shapes and stamping fashion logos or cartoon characters on the pellets. Various types of drugs have been renamed with fashionable and fancy names to connect with popular youth culture. Free trials are another strategy to promote psychotropic drug use among young people. The triads use small amounts of “free trial samples” to attract new customers. This helps to further expand the size of the market and recruit non-triad drug peddlers to sell drugs in schools. This development has forced the Hong Kong government to propose the introduction of random drug tests in secondary schools in order to contain the problem of drug use among students.

The Information Age and Triad Business

The triads have always been one of the largest producers of counterfeit CDs, VCDs, and DVDs. The rise of information technology has changed the business of the triads as much as it has changed the lives of many ordinary people. On the one hand, the rise of point-to-point free downloading systems and broadcast networks has led to the decline of pirated audio-visual products and the pornography industry, while on the other hand, the internet has helped the triads to expand their business operations across national borders, further fostering the convergence of criminal activities in mainland China and Hong Kong. The anonymity of the internet also helps to conceal their operations and identity.

Internet-driven illicit gambling is becoming one of the main sources of income for the triad syndicates. Before the spread of the internet, illicit betting on horse racing was the major gambling business of the triads, but it has now been replaced by soccer gambling. Compared to other forms of organized crime, many triad members have prospered from the gambling business, given its low risks, high profits, and perpetual nature. With only a telephone and a computer, triad members can control the business from a distance. They often cooperate with criminal partners in mainland China and Southeast Asia.Footnote 8 The convergence of triad operations across the region not only facilitates their business expansion, but it also makes police detection difficult. In order to maximize their profits derived from illicit soccer gambling, the triads also attempt to manipulate match results. In 2009, a Hong Kong court trial confirmed that a bookmaking syndicate from mainland China had tried to manipulate soccer game results in Hong Kong by providing advantages to a soccer player.

Financial Crime

Since the 1990s, there has been a change in triad organized crime from street crime to financial crime. Since many influential Hong Kong triad leaders were absorbed into the united front of the Chinese government through the ‘patriotic triad’ label, triad leaders were able to act as if they had been given a passport to enter China’s business world. This enabled them to establish relations with officials and directors of state enterprises. Lo (2010) has reported on financial crimes committed by the Sun Yee On (in collaboration with a Hong Kong listed company) through the use of social capital developed in the Chinese business world. The Sun Yee On leader and his associates were shown to have taken advantage of privileged business information obtained from mainland companies to realize enormous profits from insider trading and market manipulation.

Conclusions

From Localization to Mainlandization

In the new millennium, Hong Kong has experienced a process of mainlandization of its political, economic, and legal systems. In the socio-political arena, mainlandization is regarded as “[the] policy of making Hong Kong politically more dependent on Beijing, economically more reliant on the Mainland’s support, socially more patriotic toward the motherland, and legally more reliant on the interpretation of the Basic Law by the PRC National People’s Congress” (Lo 2007: 186). Similar tendencies appear in the sphere of organized crime. Triad societies in Hong Kong have also gone through a process of mainlandization, which is defined here as the process of making Hong Kong triad societies more reliant on mainland China for financial gain through social networking with Chinese officials, enterprises and criminal syndicates and taking advantage of legitimate and illegitimate business opportunities resulting from China’s economic growth and rising demand for goods and services. In view of increasing licit and illicit opportunities in the mainland (the pull factor) and tightening control of triad activities in Hong Kong (the push factor), triad societies have gradually shifted their business focus to mainland China.

Mainlandization is different from crime transplantation (Lintner 2004), colonization (Varese, 2006), or displacement (Broadhurst and Lee 2009). It is difficult for the Hong Kong triads to be transplanted to, or to colonize the underworld of mainland China due to the established social networks between local crime syndicates and government officials under the protective umbrella (Zhang and Chin 2008). Transplantation and colonization would create strong resistance from local criminal syndicates against Hong Kong triads (Chu 2005) and as such, the only way they could survive in the mainland is by collaborating with local Chinese counterparts in win–win situations. Moreover, although some triad activities are displaced to the mainland as a result of Hong Kong’s strengthened anti-triad regulations, the triads still maintain their business operations in Hong Kong, the base of their ‘black power’. Thus, displacement is one of the elements of mainlandization, but it is insufficient to describe the causes of convergence of triad activities between Hong Kong and mainland China.

From Triad Brotherhood to Entrepreneurship

Because of mainlandization, the survival strategy of triad societies has changed from mutual protection and triad brotherhood in the post-war decades to entrepreneurship in the 1990–2000s. Their business decisions are now made with the consideration of benefit, risk, and cost in organized crime. Using the logic of businessmen, they set objectives, choose targets, and find the right marketing strategies to achieve their money-making goal (Zhao and Li 2010). They understand the principle of minimizing cost and risk and maximizing benefit. If the ends do not justify the means, they will refrain from committing the crime. If they know the risk and cost of the crime is too high relative to the return, they will go for a more cost-effective alternative, or even consider a legitimate option if it will give them a generous financial return. These activities require stamina, good social networks, and coordination among the collaborators (Zhang 2008). Economic prosperity and a wildly fluctuating stock market in the mainland provide ample opportunities to generate profit, whereas the cost and risk are low because of the corruptibility of judicial, municipal and police officials, the absence of the rule of law, and the existence of guanxi and protective umbrellas in mainland China (Zhang and Chin 2008).

In the process of mainlandization, the triads have increasingly forged partnerships with criminal syndicates in the mainland, providing them with crime techniques and intelligence, in return for cheap manpower, drugs, and sex workers. Like organized criminal syndicates around the world (Bruinsma and Bernasco 2004; Hobbs 2001; Williams and Godson 2002), they use social networks to advance illicit enterprises. Prostitution, gambling and drugs, the three-layer cake of traditional triad activities, continue to flourish because of constant demand in the market. The triads are providing services that are not provided by the authorities. The profits generated in these markets provide sufficient incentives for the triads to pursue these criminal activities. The triads run their crime operations as if they are running corporations and enterprises. They derive a substantial and regular income from the underground economy without much competition from the legitimate commercial sector. In addition, some triad members who migrated overseas fearing communist rule over Hong Kong and Macau, have become the triads’ overseas partners. They possess the necessary skills, experience, and subcultural values and they understand the norms of triad societies. Because of the emphasis on entrepreneurship, members from different triads, or triad members and ordinary businessmen, are working together to achieve the same money-making ends, while triad brotherhood is nowadays a less-valued subcultural element.

From Cohesive Structure to Disorganization

In the past two decades, triad societies have undergone an organizational transformation. The internal structure of the modern triad society has been altered and many triads have adopted a more flexible hierarchical structure. Some traditional positions, such as Shan Chu, Sin Fung, and Cho Hai, have fallen into disuse. The rank of Pak Tsz Sin has also lost its popularity. The ranks that are still widely used in the modern triad structure are Hung Kwan, Sze Kau, and Hanging the Blue Lantern (Chu 2000).

The headquarters has also been simplified and is now usually composed of a Cho Kun (chairman), a Cha So (treasurer), and perhaps a Heung Chu (Incense Master), who are all elected from among the triad officers (Fig. 4.3). This central committee has the authority to control promotions, enforce discipline, and settle disputes, but it does not assign illegal activities to its members. The leaders do not derive any income from the activities their members engage in. In fact, the leaders derive most of their money—in the form of ‘red packets’ (lucky money)—from occasions such as Chinese New Year, initiation ceremonies and promotion ceremonies (Chu 2000).

Structure of a modern triad society (Chu 2000: 28)

The most organized part of a triad society can be found at the middle level of territorially based gangs headed by a Hung Kwan (Red Pole) and consisting of Sze Kau (49) members and Blue Lanterns (Fig. 4.3). These gangs are organized by area and if the area is large enough, one or more gangs might occupy the same area while working under different area bosses. They engage in criminal activity at the street level and their influence extends to local youth gangs. Violence is often used to maintain and exert the gang’s dominance over the area (Chu 2000).

There have also been radical changes in the ideology and aims of the triads. Rituals and initiation ceremonies have been greatly simplified or even abandoned and there has been a decrease in the use of hand signs and poems as secret methods of communication. The traditional triad principles of brotherhood and loyalty have more or less disappeared or have been modified, depending largely on the members’ interpretations. Gang cohesiveness and member loyalty have begun to diminish. Procedures regarding promotion, recruitment, and communication have not been followed closely and the headquarters of triad societies no longer have full control over the sub-branches. Incidents of internal conflict have increased. It is now up to the individual triad gangsters instead of the organization to run the illicit businesses. Members of different triad societies can team up to pursue their own financial goals, and permission from the organization is no longer necessary (Chu 2000, 2005; Zhao and Li 2010).According to a police triad expert, “since triads are disorganized, it is more appropriate to name them gangs. They are opportunists, you can find their footsteps wherever the money lies” (Ming Pao 2007: A12).

There are several reasons for the changes in triad structure. The long chain of command and the strict hierarchical structure of the triads increased the risk of exposure of their activities, especially after the enactment of OSCO and other related legislation. As the triads are moving toward entrepreneurship, greed and profit rather than brotherhood have become the driving factors in building bonds between triad members, and this has diminished the importance of triad rituals. In addition, triad rituals and titles also increase the risk of prosecution as they are essential elements in the prosecution of triad-related offences. Consequently, instead of facilitating triad operations, these rituals pose a risk to the organization. In view of the government’s increased control of triad activities and a rapidly changing social environment, triads have to be flexible in their operational structure and be responsive to changes in both market demands and social conditions (Broadhurst and Lee 2009).

From a ‘Patriotic Triad’ Policy to Cross-Border Collaboration in Combating Organized Crime

The ‘united front’ effect of the ‘patriotic triad’ policy implemented two decades ago has begun to diminish. The Chinese government has become aware of the potential risk of triad displacement to the mainland. In order to control this trend, the Chinese government amended its Criminal Law in 2002 and Article 294 now stipulates that members of triad societies outside China coming to recruit members or develop the societies in China will be sentenced to 3–10 years of imprisonment.

Since 2000, cross-border cooperation between Hong Kong and mainland China has become more formalized and frequent. Public security officials in the mainland and the Hong Kong police started launching large-scale and successful joint operationsFootnote 9 against the criminal syndicates (Xiang 2004). In addition, the ‘Arrangements on the Establishment of a Reciprocal Notification Mechanism between the Mainland Public Security Authorities and the Hong Kong Police’, which began operation in 2001, marked a milestone in formal administrative agreements to combat cross-border crime. The cooperative framework has been further strengthened in later years, including the opening of a Beijing Office in 2002 to assist Hong Kong citizens who have been arrested and detained in China (Broadhurst and Lee 2009); the setting up of a working group to outline strategies for combating cross-border crime; and the launch of a 24-hour notification system in 2002–2003 to facilitate immediate exchange of information and intelligence about commercial, drug-related, and violent crime (Xiang 2004). The various policy and administrative changes reflect that the regulation of triad organized crime has become a major concern of the governments on both sides of the Chinese border.

To conclude, the above observation that patterns of organized crime are affected by the political and socioeconomic changes in a society has also been made in the West (see, for example, Hobbs 2001; Paoli 2003; Shelley 2003). In the context of Hong Kong, triad societies have moved from a cohesive structure and a fixed territorial base toward more reliance on flexible and instrumental social networks. They are entrepreneurially oriented and involved in a wide range of licit and illicit activities that are based in Hong Kong but have spread to mainland China in a process of mainlandization that has already taken place in the legal, political, social, and economic spheres of Hong Kong.

Notes

- 1.

They were 14K, Big Circle Gang, Shui Fong (Wo On Lok), Wo Hop To, Wo Shing Wo, Wo Shing Yee, Wo Yee Tong, Wo Kwan Lok, Li Kwan, Chuen Yat Chi, Lo Tung, Lo Wing, Dan Yee, HunanGang, Sun Yee On, Fuk Yee Hing, Luen Kung Lok, Luen Ying Society, and Hwok Lo.

- 2.

Amongst them were Yip Kai Foon, who used AK47 assault rifles to rob jewelry stores; Cheung Tse-keung, a notorious kidnapper, robber and arms smuggler, who kidnapped several business tycoons in Hong Kong; and Kwai Ping-hung, formerly Hong Kong's most wanted man for shooting down police officers while resisting arrest.

- 3.

The PRC-Hong Kong-Macau police started their first semi-official cooperation through the structure of INTERPOL in 1985 to combat coinage crime, smuggling, drugs, and hijacking, and this enforcement platform was extended to other types of organized crimes such as kidnapping, car thefts, and commercial crimes in 1987. Between 1987 and 1997, Guangdong and Hong Kong exchanged 471 notes for mutual assistance (Wong 2004).

- 4.

In post-war decades, both the Sun Yee On and the 14K triads were closely associated with the Taiwanese government.

- 5.

The failure was evidenced in the number of applications to the TRS and the number of successful renounced triad members. About 1,100 triad members applied to renounce their triad membership. Among them, about three quarters were inmates of prisons, and about 45% were young people (between 11 and 20 years old). Eventually, only about 620 applicants successfully renounced (Lo 1991). The scheme was described as ineffective because of its temporary nature and shortage of staff (Huque 1994).

- 6.

A higher score out of 10 indicates less perceived corruption.

- 7.

The street price of ketamine is HK$100 a gram, compared to HK$600 a gram for heroin and HK$80 for a single ecstasy tablet (South China Morning Post 29 November 2009).

- 8.

According to several news sources, 2010 was an active year in illegal cross-border soccer gambling. In the first half of 2010, over 670 cases were reported to the police in various parts of China; many of them had overseas connections. During the World Cup in July 2010, a joint police operation between Hong Kong and Guangdong smashed a cross-border bookmaking syndicate, which led to the arrest of 74 criminals in Hong Kong and 29 in southern China, and the seizure of around 7 billion yuan (679.9 million pounds) of illegal bets (Reuters July 9, 2010). The International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL) disclosed that from June 11 to July 11, 2010, police in China, Hong Kong, Macao, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand raided nearly 800 illegal gambling networks across Asia that had accepted an estimated US$155 million in bets; more than 5,000 people were arrested and US$10 million was seized (Volkov 2010).

- 9.

According to the Hong Kong police, operation ‘Fire Phoenix’ was aimed at targeting triad activities, drug trafficking, violent crime, illegal firearms, and organized illegal bookmaking activities. There were approximately 2,000 police officers involved in the operation and 990 persons were arrested. In this operation, the police dismantled 41 crime syndicates and seized over 80 pieces of offensive weapons, four hand-guns and 30 rounds of ammunition, 5,000 g of heroin, 1,000 g of ice, over 17,000 tablets of ecstasy, over 17,000 g of ketamine, over 100 kg of cannabis, over 15,000 tablets of psychotropic substances, about $34 million worth of betting slips, and $160,000 cash (Government Information Centre Press Release, 25 June 2002, cited from Xiang 2004: 110).

References

Broadhurst, R., & Lee, K. W. (2009). The transformation of triad ‘dark societies’ in Hong Kong: The impact of law enforcement, socio-economic and political change. Security Challenges, 5(4), 1–38.

Bruinsma, G., & Bernasco, W. (2004). Criminal groups and transnational illegal markets: A more detailed examination on the basis of social network theory. Crime, Law and Social Change, 41, 79–94.

Cheung, T. S., & Lau, C. C. (1981). A profile of syndicate corruption in the police force. In R. P. L. Lee (Ed.), Corruption and its control in Hong Kong (pp. 199–221). Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press.

Chin, K. (1990). Chinese subculture and criminality: Non-traditional crime group in America. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Chin, K. (1999). Smuggled Chinese: Clandestine immigration to the United States. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Chin, K. (2003). Heijin: Organized crime, business, and politics in Taiwan. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Chu, Y. K. (2000). The triads as business. London: Routledge.

Chu, Y. K. (2005). Hong Kong triads after 1997. Trends in Organized Crime, 8(3), 5–12.

Curtis, G. E., Elan, S. L., Hudson, R. A., & Kollars, N. A. (2003). Transnational activities of Chinese crime organizations. Washington DC: Federal Research Division.

Fight Crime Committee. (1986). A discussion document on options for changes in the law and in the administration of the law to counter the triad problem. Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Finckenauer, J. O., & Chin, K. (2007). Asian transnational organized crime and its impact on the United States. Washington DC: US Department of Justice.

Harris, R. (2003). Political corruption: In and beyond the National State. London: Routledge.

Hobbs, D. (2001). The firm: Organizational logic and criminal culture on a shifting terrain. British Journal of Criminology, 41, 549–560.

Huque, A. S. (1994). Renunciation, destigmatisation and prevention of crime in Hong Kong. Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 33(4), 338–351.

Jiang, G. (2008). Status of law and corruption control in post-reform ChinaChina. Ph.D. thesis, City University of Hong Kong.

Laidler, K. A. J., Hodson, D., & Traver, H. (2000). The Hong Kong drug market: A report for UNICRI on the UNDCP global study in illicit drug markets. Hong Kong: Centre of Criminology, University of Hong Kong.

Leong, A. V. M. (2002). The ‘bate-ficha’ business and triads in Macau casinos. Law and Justice Journal, 2(1), 83–99.

Lintner, B. (2004). Chinese organized crime. Global Crime, 6(1), 84–96.

Liu, B. (2001). The Hong Kong triad societies. Before and after the 1997 change-over. Hong Kong: Net e-Publishing.

Lo, T. W. (1984). Gang dynamics. Hong Kong: Caritas.

Lo, T. W. (1991). Law and order. In Y. W. Sung & M. K. Lee (Eds.), The other Hong Kong report 1991 (pp. 117–134). Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Lo, T. W. (1992). Law and order. In J. Y. S. Cheng & P. C. K. Kwong (Eds.), The other Hong Kong report 1992 (pp. 127–148). Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Lo, T. W. (1993). Corruption and politics in Hong Kong and China. Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Lo, T.W. (1995). Patriotic triads and the 1997 exodus. Paper presented at the Conference on Hong Kong and its Pearl River Delta Hinterland: Links to China, Links to the World, organized by the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, May 4–6, 1995.

Lo, T.W. (2002). The Map of Triad Juvenile Gangs. Hong Kong: Youth Studies Net, City University of Hong Kong. Retrieved February 23, 2010, from http://www.cityu.edu.hk/prj/YSNet/gangwork/01/index.htm

Lo, S. (2007). The mainlandization and recolonization of Hong Kong: A triumph of convergence over divergence with mainland China. In J. Y. S. Cheng (Ed.), The Hong Kong special administrative region in its first decade (pp. 179–232). Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

Lo, T. W. (2010). Beyond social capital: Triad organized crime in Hong Kong and China. British Journal of Criminology, 50, 851–872.

Lo, T.W. (2011). Resistance to the mainlandization of criminal justice practices: A barrier to the development of restorative justice in Hong Kong. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. doi:10.1177/0306624X11405481 .

Ming Pao. (2007, April 13). p. A12.

Paoli, L. (2003). Broken bonds: Mafia and politics in sicily. In R. Godson (Ed.), Menace to society: Political-criminal collaboration around the world (pp. 27–70). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Shelley, L. I. (2003). Russia and Ukraine: Transition or tragedy. In R. Godson (Ed.), Menace to society: Political-criminal collaboration around the world (pp. 199–230). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

So, E. C. K. (2011). Social capital and Young drug dealers in Hong Kong: A preliminary study. Crime and Criminal Justice International, 16(1), 103–125.

Varese, F. (2006). How mafia’s migrate: The case of the ndrangheta in northern Italy. Law and Society, 40(2), 411–444.

Volkov, A. (2010, October 4). INTERPOL exposes illegal soccer gambling networks in Asia. The Epoch Times. Retrieved on October 5, 2010, from http://www.theepochtimes.com/n2/content/view/39317/

Williams, P., & Godson, R. (2002). Anticipating organized and transnational crime. Crime, Law and Social Change, 37, 311–355.

Wong, K.C. (2004). Fighting cross-border crimes between China and Hong Kong. Unpublished manuscript.

Xiang, F. (2004). Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters between Hong Kong and the Mainland. MPhil thesis, The University of Hong Kong.

Zhang, S. (2008). Chinese human smuggling organizations: Families, social networks, and cultural imperatives. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Zhang, S., & Chin, K. (2002). Enter the dragon: Inside Chinese human smuggling organizations. Criminology, 40, 737–768.

Zhang, S., & Chin, K. (2003). The declining significance of triad societies in transnational illegal activities: A structural deficiency perspective. British Journal of Criminology, 43, 469–488.

Zhang, S. X., & Chin, K. (2008). Snakeheads, mules, and protective umbrellas: A review of current research on Chinese organized Crime. Crime, Law and Social Change, 50, 177–195.

Zhao, G., & Li, Z. (2010). An analysis of current organized crime in Hong Kong. Journal of Chinese Criminal Law, 4, 96–109.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wing Lo, T., Kwok, S.I. (2012). Traditional Organized Crime in the Modern World: How Triad Societies Respond to Socioeconomic Change. In: Siegel, D., van de Bunt, H. (eds) Traditional Organized Crime in the Modern World. Studies of Organized Crime, vol 11. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3212-8_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3212-8_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-3211-1

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-3212-8

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)