Abstract

‘Preventability’ is a crucial concept in the literature on adverse drug reactions (ADRs). We have carried out a systematic review in order to identify and analyse the approaches used to define ‘preventability’ in relation to ADRs. We have restricted this investigation to definitions of preventability and have not dealt with other aspects. We searched MEDLINE (1963–April 2009) and EMBASE (1980–April 2009), without language restriction, for papers in which preventability of ADRs was likely to be defined.

We found 234 papers, of which we retrieved 231. Of these, 172 either contained original definitions of preventability or referred to other papers in which preventability was defined. Forty contained no definition, and 19 were not relevant. In the 172 papers selected, we identified eight different general approaches to defining the preventability of ADRs: (1) analysis without explicit criteria; (2) assessment by consensus; (3) preventability linked to error; (4) preventability linked to standards of care; (5) preventability linked to medication-related factors; (6) preventability linked to information technology; (7) categorization of harmful treatments in explicit lists; and (8) a combination of more than one approach.

These approaches rely on two general methods: the judgement of one or more investigators or the use of pre-defined explicit criteria; neither is satisfactory. Specific problems include the weakness of consensus as a method (since experts can agree and yet be wrong), inadequacy of definition of standards of care, and circularity in several definitions of preventability. Furthermore, attempts to list all preventable effects are bound to be incomplete and will not always apply to an individual case.

We conclude that an approach based on analysis of the mechanisms of adverse reactions and their clinical features could be preferable; such an approach is described in a companion paper (Part II) in this issue of Drug Safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Preventability (sometimes referred to as ‘avoidability’) is a crucial concept in the literature on adverse events, including suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and other drug-related harms (sometimes called ‘drug-related morbidity’, ‘drugrelated problems’ or ‘adverse drug events’). The better the concept can be defined the more useful it will be.

There are two aspects to preventability: whether in principle an event is preventable in the absence of error, and, if it is, whether we can in fact prevent it. For example, penicillin hypersensitivity reactions can in principle be avoided in patients known to be susceptible, by not giving the drug; however, in practice such reactions will still occur, for example, because information is not available to the prescriber, or because tests of susceptibility, such as skin prick tests, are not completely reliable.

We are aware that harms are never absolutely preventable, although any intervention that reduces the probability of harm can be said to have made a contribution to prevention. In a companion paper (Part II) in this issue of Drug Safety[1] we propose an approach to preventability based on analysis of the mechanisms of ADRs and their clinical manifestations. Here we have carried out a narrative systematic review of the ways in which the preventability of ADRs has been defined and discuss the limitations of those definitions.

1. Searching the Literature

We systematically searched MEDLINE (1963– April 2009) and EMBASE (1980–April 2009), without language restriction, for papers in which preventability of ADRs was likely to be defined. We investigated three search strategies.

First, we used the following search terms: ‘prevent*’, ‘avoid*’ and numerous terms for harms from drugs (e.g. ‘side effect*’, ‘adverse effect*’, ‘adverse drug reaction*’, ‘adverse drug event*’, ‘drug induced harm*’). This yielded over 200 000 hits and we did not pursue this strategy.

Secondly, we took a corpus of 55 papers that we had previously identified and compiled a list of all papers that referred to those 55 using ISI Web of Science. This yielded over 8000 hits and we abandoned that strategy too.

Thirdly, we searched the databases using the following terms: ‘preventab*’, ‘avoidab*’, ‘drug toxicity/’, ‘medication errors/’, ‘side effect*’, and ‘adverse drug reaction*’. This yielded 640 references in EMBASE and 532 references in MEDLINE.

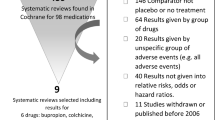

After choosing relevant papers (on the basis of titles and abstracts, looking for text that referred to the prevention of harms from medicines) and after removing 149 replicates, we were left with 147 papers, of which we were able to retrieve 144. In addition, we retrieved another 87 papers from the reference lists of those 144, yielding 231 in all. This search strategy (illustrated in figure 1) was similar to, but more extensive than, that used by Goettler et al.[2] in their meta-analysis of the frequency with which admissions to hospital were due to preventable ADRs, a search that yielded 14 papers for analysis.

After reading those 231 papers we were able to reduce the corpus to 172 papers that either contained original definitions of preventability or referred to other papers that contained suchdefinitions (see appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.adisonline.com/DSZ/A32); 40 contained no definition and 19 were not relevant.

2. Summary of Findings

We identified eight different approaches to defining the preventability of ADRs in the papers we retrieved:

-

1.

analysis without explicit criteria;

-

2.

assessment by consensus;

-

3.

preventability linked to error;

-

4.

preventability linked to standards of care;

-

5.

preventability linked to medication-related factors;

-

6.

preventability linked to information technology;

-

7.

categorization of harmful treatments in explicit lists;

-

8.

combinations of more than one of these approaches.

3. General Comments

3.1 Analysis Without Explicit Criteria

In 1971, Melmon[3] estimated that 3–5% of admissions to hospital arose from ADRs, which he defined as “all unwanted consequences of drug administration, including administration of the wrong drug (or drugs), to the wrong patient in the wrong dosage (form, amount, route or interval), at the wrong time and for the wrong disease.” He noted that ‘classic’ immunological reactions made up less than 30% of all reactions and concluded that “the remaining 70–80 percent are predictable … Most [of them] without compromise of the therapeutic benefits of the drug.” It seems, therefore, that Melmon believed that all medication errors and all ‘predictable’ ADRs are preventable. However, he did not define predictability.

Burnum[4] criticized Melmon and others: “some authors have assumed, but without supporting data, that the vast majority of adverse drug reactions occur needlessly and are preventable.” He examined 42 ADRs, describing 19 (45%) as unavoidable and 23 (55%) as “unnecessary and potentially preventable.” The latter involved an element of error on the part of one or more of the physician, pharmacist or patient; for example, the prescribing of a drug that was contraindicated. Burnum appears to have been the first to state explicitly that assessment was required to decide whether a reaction was preventable, but he did not state what criteria he used.

3.2 Assessment by Consensus

Two general forms of consensus have been used: (a) agreement among peers without preset criteria; and (b) the establishment of criteria by a process of consensus, such as the Delphi technique.

Some authors have been content to ensure that at least one colleague agrees with the original assessment of preventability: “Preventability was defined on the basis of the initial reviewer’s interpretation and the second reviewer’s confirmation of whether the ADE could have been prevented.”[5] An admission to emergency hospital care was judged to be ‘preventable’ in a review of case notes if at least two of three reviewers stated that it was.[6] Similarly, when examining whether deaths in hospital were preventable, others decided only on the basis of how closely raters agreed.[7]

Some have examined the intensity of a clinician’s feeling that a reaction is preventable, but have not tested the method. Baker et al.[8] asked clinicians to grade preventability on a 6-point scale from “virtually no evidence of preventability” to “virtually certain evidence of preventability.” The study was not confined to harm from drugs, but included, for example, a steroid-dependent patient not given steroids in hospital, an omission that led to adrenal insufficiency, as an example of an event that clinicians were virtually certain was preventable. [9]

Morris and Cantrill[10] used the Delphi method to ‘validate’ indicators of preventable harm from medicines, seeking agreement from 17 doctors and pharmacists; they achieved reasonable consensus on only 24 of 41 indicators. As they concluded, “although we have mechanisms to identify preventable drug-related hospital admissions (outcomes), identifying the process of care that is needed to prevent their occurrence is far more challenging.”

Consensus is only one step beyond individual judgement; it is possible for experts to agree and yet be wrong.[11]

3.3 Preventability Linked to Error

When harm arises from a medication error it is potentially preventable. This does not translate easily into ‘never events’, because of the nature of medication errors, which, like other errors of conscious acts, are part of the human condition.[12] If such errors are in fact to be averted, systems need to be made robust in the face of human error — for example, by simplification, by greater automation, and by increased checking; unfortunately, removing errors in one part of a system may introduce errors elsewhere.

One definition of a medication error is “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer.”[13] This suggests that error and preventability run together. However, “few authors have formally discussed the relationship between preventability and medication errors (i.e. whether errors are by definition preventable or whether every preventable adverse event is necessarily associated with an error).”[14] While authors assumed a ‘strong relationship’ between preventable harms and errors, that is not at all evident, at any rate when Hallas’s grading[15] (see section 3.4) suggests that “effort exceeding the obligatory demands” would be required. Nor will careful assessment of benefit and harm always lead to the same decision about preventive measures when the measures themselves are not risk-free. For example, the efficacy of clopidogrel may be reduced when it is given with a proton pump inhibitor (to reduce the risks of gastric haemorrhage); here one risk is substituted for another.[16]

Bates and colleagues[17] have repeatedly used the criterion that “adverse drug events [were considered to be] preventable if they were due to an error or were preventable by any means currently available,” although in later versions ‘or’ was changed to ‘and’, an important amendment.[18,19] In its later version, this circular definition implies that only harm due to error would be classified as preventable. In some instances, they added that “by definition, all potential adverse drug events were considered preventable,”[18] which appears contradictory.

3.4 Preventability Linked to Standards of Care

Noting the wide variation in observed rates of drug-related hospital admissions, from 2.9% to 20%, Hallas et al.[15] attributed these mainly to differences in the quality and intensity of data collection, which remain important.[20] They clearly recognized the general difficulties in attributing causation, and advocated a version of the criteria suggested by Karch and Lasagna,[21] linked to an assessment of the extent to which the drug-related harm contributed to hospital admission (from ‘dominant’ to ‘not contributing’). They considered whether the event could have been avoided by “appropriate measures taken by the health service personnel” (table I). All ‘definitely avoidable’ drug-related harm in this study apparently resulted from error or miscommunication.

Criteria of Hallas et al.[15] for avoidability of events associated with drug therapy

Many later authors[22–24] have used these criteria. But the obverse of these criteria has also been used: “We defined as non-avoidable, [adverse drug effects] that occurred in well-indicated and well-managed therapy with reasonable weighing up of risks and benefits.”[25]

Some have set perfection as the criterion. For example, Darchy et al.[26] defined a preventable event as one “that should not occur if management is the best that medical science can provide.” By this exacting criterion, 51% of drug-related admissions to an intensive care unit were preventable. Similarly, Thomas and Brennan[27] stated: “An adverse event was considered preventable if it was avoidable by any means currently available … unless that means was not considered standard care”; this is a circular definition.

A definition of drug-related harm as preventable “if drug treatment, or lack thereof, was inconsistent with current best practice” is perhaps less stringent.[28] Others were content with “the standard of care expected from an average practitioner who practices in that area [of clinical medicine].”[29]

Hayward and Hofer,[30] using a set of 111 deaths in hospital, considered the question “when a reviewer classifies a death as definitely or probably preventable… is there a 90% chance or a 10% chance that a death would have actually been prevented if care had been optimal?” They independently examined case notes and graded deaths as definitely, probably, uncertainly, not probably, or definitely not preventable. They found considerable differences between reviewers.

Some authors have used negligence as a marker of preventability.[31,32] However, standards of care are too poorly defined to make this method useful, particularly if comparisons are required.

3.5 Preventability Linked to Medication-Related Factors

In an analysis of drug-related harm in older adults, Gosney and Tallis[33] used three straightforward criteria for avoidability. “Prescriptions were analysed to identify: drugs to which the patient had a well documented adverse reaction; drugs contraindicated in the light of the patient’s diagnosis; and interacting drugs.” For the last category they confined themselves to “well known interactions”.

Hartwig et al.[34] considered whether, in the circumstances, the drug used and the dose, route and frequency of administration were appropriate; whether the adverse effect was the result of a documented drug allergy and whether appropriate preventive laboratory monitoring had been undertaken.

Kelly and co-workers examined fatal,[35] permanently disabling,[36] life-threatening,[37] and significant[38] adverse events that may have been due to drugs, and assessed preventability using criteria amended from those first suggested by Schumock and Thornton[39] (table II). They estimated that 57% of episodes of fatal harm from drugs described in 447 literature abstracts could have been “prevented by a pharmacist,” which may be different from overall preventability. The same criteria were used by other groups, [40] and others have examined the preventability of hospital readmissions related to ADRs.[41,42]

Original criteria of Schumock and Thornton[39] for determining the preventability of an adverse drug reaction

When Kunac and Reith[43] investigated drug-related harm in children in New Zealand they observed that, when using the criteria of Schumock and Thornton, [39] overall agreement was only ‘fair’ (κ=0.37; 95% CI 0.33, 0.41) for preventable events and no better than ‘moderate’ for not preventable events (κ = 0.47; 95% CI 0.43, 0.51).

The original criteria formulated by Schumock and Thornton[39] were not entirely satisfactory. They were therefore later modified by including previous ADRs not only to individual drugs but also to classes of drug.[44] By the amended definition, the most common reason for categorizing drug-induced harm as preventable was a positive response to the question “was a toxic serum drug level [or lab test] documented?” This criterion seems excessively restrictive. Dormann et al.[45] modified the criteria further; if there was no alternative form of treatment (e.g. for antineoplastic drugs) or a positive benefit-to-risk ratio was assigned for the causative drug, ADRs were judged to be ‘tolerable’.

Snyder et al.[46] considered that “preventable ADEs [adverse drug events] and non-intercepted PADEs [preventable adverse drug events] were considered medication errors that should have been prevented or intercepted by effective medication safety practices and/or systems.” This circular definition was further informed by an adaptation of the National Coordinating Council Medication Error Reporting and Prevention index preventability criteria, essentially a minor adaptation of those of Schumock and Thornton. [39]

Many other authors have based their assessments of preventability either explicitly or implicitly on the A/B classification of ADRs, which proposes that not all reactions are dose-related but that those that are are preventable.[47] We have elsewhere discussed the many difficulties with this classification, including the fact that all reactions are necessarily dose-related,[48] but not necessarily preventable.

Some have used the Summaries of Product Characteristics (SPC) as a touchstone for defining preventability.[49] If a drug was prescribed not in accordance with the SPC and if, furthermore, failure to adhere to the SPC was a known risk factor for the adverse event, it was regarded as avoidable. The deficiencies of SPCs are well known.[50]

3.6 Preventability Linked to Information Technology

Some authors have considered the probability that information systems of different sophistication would prevent harm.[51] Bobb et al.[52] noted that “Prescribing errors related to illegible handwriting, drug/allergy interactions, wrong dose formulation, and incomplete orders were judged to be preventable in almost all cases. Prescribing errors due to inaccurate or missing patient medication histories and medication omissions would likely be unpreventable by most currently available CPOE [computerized provider order entry] systems. However, CPOE systems vary significantly in their capability to apply complex decision support algorithms that integrate medical and medication history, laboratory values and dosing guidelines. Prescribing errors were classified as possibly preventable when such advanced CPOE clinical decision support features would have prevented them.”

In a 2008 study, Kuo et al.[53] used a coding system for medication errors called Medication Error Types, Reasons and Informatics Preventability (METRIP). With this, they sought to classify each error “according to whether or not existing informatics technology (IT), if fully developed and implemented, would have prevented the error. IT features that could have prevented an error included common functionalities available in most computerized provider order entry (CPOE) systems and electronic medical records (EMR); for example, having a drug selection list, dosage selection, laboratory monitoring, drug allergy or interaction checks, and direct links with pharmacies and other care facilities.”

We note the circularity of these definitions. Furthermore, the specificity of automatic alert systems tends to be low, at least as judged by the extent to which clinicians accept the proffered advice;[54] and their sensitivity is difficult to establish, as the number of errors missed cannot readily be determined. In a computerized alert system at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, only 54 episodes of drug-related harm (and 113 of potential harm) were detected in 2773 reports.[55]

3.7 Categorization of Harmful Treatments in Explicit Lists

One way of circumventing the problem of defining criteria for preventable drug-related harm without circularity (it is preventable if we can prevent it) is to use an extensional definition,[56] i.e. to create a list of ‘potentially inappropriate drugs’ and label all those who require hospital treatment for harm associated with one of those drugs as suffering from preventable harm. An example is the Beers criteria.[57–59] This strategy was used by Budnitz et al.,[60] who supplied a list of potentially inappropriate drugs and then looked at emergency department visits by older people with harms attributable to those drugs. The drugs on the Beers list accounted for only about 9% of cases of drug-induced harm, illustrating the limitations of this method.

3.8 Combined Criteria

Combinations of methods carry the disadvantages of the individual methods. Robertson and MacKinnon[61] combined explicit criteria and consensus when they used the Delphi technique to interrogate expert clinical pharmacologists and expert geriatricians about preventable drug-related morbidity in elderly people. They based their list on principles expounded by Hepler and Strand.[62] For harm from a medication to be preventable, it had to demonstrate four defining characteristics: (i) health professionals should be able to recognize significant problems with this pattern of care in most older adults; (ii) they should be able to foresee the possibility of the (harmful) outcome in most older patients if the problems were not resolved; (iii) most of them should be able to see how they would change the pattern of care in order to prevent the harmful outcome; and (iv) most of them should actually change the pattern of care. One advantage of this approach is that, having once generated a list of codeable events of sufficient sensitivity and specificity for preventable drug-related harm, discharge data can be searched to identify the codes and draw inferences about the quality of care, an approach adopted by MacKinnon and Hepler.[63] Howard et al.[64] used a form of the Hepler-Strand criteria: (i) drug-related morbidity was preceded by a recognizable drug therapy problem; (ii) given the problem, the morbidity would have been reasonably foreseeable; (iii) the cause was identifiable with reasonable probability; and (iv) the cause of the drug-related morbidity could have been reasonably controllable within the context and objectives of treatment.

The Clinical Pharmacy Group in Granada has developed and used a test of preventability, originally developed by Baena et al.,[65] which contains elements of Schumock and Thornton, but also includes elements of error (table III).

Given that decisions on preventability using this schema are made after the event, there is likely to be a bias towards giving positive answers to questions regarding, for example, the inappropriateness of the dose or the duration of treatment.

Olivier et al.[66] drew attention to methods for measuring the avoidability of adverse drug effects, but pointed out that no authors had clearly evaluated the validity of their methods. They examined both the content validity and the reliability of a French preventability scale with several interesting features: it takes as a starting point the assumption that ADRs that have not previously been described are unavoidable; they considered the potential part played by the medication process, the medicine and patient factors in the adverse effects observed; and they devised a scoring system that allowed a graded response from −13 (clearly avoidable) to +8 (inevitable). Disappointingly, inter-rater reliability was not very good, with an average k value of 0.11 over all the domains. As the authors concluded, the construction of a valid scale is a prolonged and fastidious undertaking.

The Granada schema for determining whether drug-related harm can be avoided[65]

Winterstein et al.[67] questioned the importance of having explicit criteria for assessing preventability. Their meta-analysis showed no appreciable difference in the prevalence of preventable adverse effects between six trials with explicit criteria and nine without.

4. Conclusions

This analysis suggests that of the several definitions of preventability of ADRs, none fits all circumstances, and when the reliability of these definitions has been examined they have been found to be imperfect. This implies that previous estimates of the extent to which ADRs are preventable in a population are likely to be misleading.

In the companion to this paper (Part II, in this issue of Drug Safety),[1] we propose a scheme that provides a complete analysis of the problem of preventability of ADRs, by considering the mechanism of the reaction, its dose-responsiveness, its time-course, and individual susceptibility factors.

References

Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Preventability of drug-related harms — part II: proposed criteria, based on frameworks that classify adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf 2010; 33(11): 995–1002

Goettler M, Schneeweiss S, Hasford J. Adverse drug reaction monitoring: cost and benefit considerations. Part II: cost and preventability of adverse drug reactions leading to hospital admission. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1997; 6 Suppl. 3: S79–90

Melmon KL. Preventable drug reactions: causes and cures. N Engl J Med 1971; 284(24): 1361–8

Burnum JF. Preventability of adverse drug reactions. Ann Intern Med 1976; 85(1): 80–1

Takata GS, Mason W, Taketomo C, et al. Development, testing, and findings of a pediatric-focused trigger tool to identify medication-related harm in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics 2008; 121: e927–35

Bigby J, Dunn J, Goldman L, et al. Assessing the preventability of emergency hospital admissions. Am J Med 1987; 3: 1031–6

Dubois RW, Brook RH. Preventable deaths: who, how often, and why? Ann Intern Med 1988; 109(7): 582–9

Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V, et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. CMAJ 2004; 170(11): 1678–86

Baker GR. e-Appendix 3: brief description of clinical details of adverse events occurring in 255 patients, by corresponding maximum degree of preventability [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/data/170/11/1678/DC3/1 [Accessed 2009 Jun 21]

Morris CJ, Cantrill JA. Preventing drug-related morbidity: the development of quality indicators. J Clin Pharm Ther 2003; 28(4): 295–305

Buetow SA, Sibbald B, Cantrill JA, et al. Appropriateness in health care: application to prescribing. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45(2): 261–71

McDowell SE, Ferner HS, Ferner RE. The pathophysiology of medication errors: how and where they arise. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 67(6): 605–13

Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH. Clarifying adverse drug events: a clinician’s guide to terminology, documentation, and reporting. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140(10): 795–801

Kanjanarat P, Winterstein AG, Johns TE, et al. Nature of preventable adverse drug events in hospitals: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2003; 60(17): 1750–9

Hallas J, Harvald B, Gram LF, et al. Drug related hospital admissions: the role of definitions and intensity of data collection, and the possibility of prevention. J Intern Med 1990; 228(2): 83–90

Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 2009; 301(9): 937–44

Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events: implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1995; 274(1): 29–34

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Avorn J, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events in nursing homes. Am J Med 2000; 109(2): 87–94

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003; 289(9): 1107–16

Ferner RE. The epidemiology of medication errors: the methodological difficulties. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 67(6): 614–20

Karch FE, Lasagna L. Adverse drug reactions: a critical review. JAMA 1975; 234: 1236–41

Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ 2004; 329(7456): 15–9

van der Hooft CS, Dieleman JP, Siemes C, et al. Adverse drug reaction-related hospitalisations: a population-based cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008; 17: 365–71

Franceschi M, Scarcelli C, Niro V, et al. Prevalence, clinical features and avoidability of adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to a geriatric unit: a prospective study of 1756 patients. Drug Saf 2008; 31(6): 545–56

Raschetti R, Morgutti M, Menniti-Ippolito F, et al. Suspected adverse drug events requiring emergency department visits or hospital admissions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 54(12): 959–63

Darchy B, Le Mière E, Figuérédo B, et al. Iatrogenic diseases as a reason for admission to the intensive care unit: incidence, causes, and consequences. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159(1): 71–8

Thomas EJ, Brennan TA. Incidence and types of preventable adverse events in elderly patients: population based review of medical records. BMJ 2000; 320: 741–4

Zed PJ, Abu-Laban RB, Balen RM, et al. Incidence, severity and preventability of medication-related visits to the emergency department: a prospective study. CMAJ 2008; 178(12): 1563–9

Sari AB, Cracknell A, Sheldon TA. Incidence, preventability and consequences of adverse events in older people: results of a retrospective case-note review. Age Ageing 2008; 37(3): 265–9

Hayward RA, Hofer TP. Estimating hospital deaths due to medical errors: preventability is in the eye of the reviewer. JAMA 2001; 286(4): 415–20

Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med 1991; 324(6): 370–6

Brennan TA, Hebert LE, Laird NM, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with adverse events and substandard care. JAMA 1991; 265(24): 3265–9

Gosney M, Tallis R. Prescription of contraindicated and interacting drugs in elderly patients admitted to hospital. Lancet 1984; 2(8402): 564–7

Hartwig SC, Siegel J, Schneider PJ. Preventability and severity assessment in reporting adverse drug reactions. Am J Hosp Pharm 1992; 49(9): 2229–32

Kelly WN. Potential risks and prevention: part 1. Fatal adverse drug events. Am J Health SystPharm 2001; 58(14): 1317–24

Kelly WN. Potential risks and prevention: part 2. Drug-induced permanent disabilities. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001; 58(14): 1325–9

Marcellino K, Kelly WN. Potential risks and prevention: part 3. Drug-induced threats to life. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001; 58(15): 1399–405

Kelly WN. Potential risks and prevention: part 4. Reports of significant adverse drug events. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001; 58(15): 1406–12

Schumock GT, Thornton JP. Focusing on the preventability of adverse drug reactions. Hosp Pharm 1992; 27(6): 538

Gholami K, Shalviri G. Factors associated with preventability, predictability, and severity of adverse drug reactions. Ann Pharmacother 1999; 33(2): 236–40

Ruiz B, García M, Aguirre U, et al. Factors predicting hospital readmissions related to adverse drug reactions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008; 64(7): 715–22

Leendertse AJ, Egberts ACG, Stoker LJ, et al., the HARM Study Group. Frequency of and risk factors for preventable medication-related hospital admissions in the Netherlands. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168(17): 1890–6

Kunac DL, Reith DM. Preventable medication-related events in hospitalised children in New Zealand. N Z Med J 2008; 121: 17–32

Ducharme MM, Boothby LA. Analysis of adverse drug reactions for preventability. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61(1): 157–61

Dormann H, Neubert A, Criegee-Rieck M, et al. Readmissions and adverse drug reactions in internal medicine: the economic impact. J Intern Med 2004; 255: 653–63

Snyder RA, Abarca J, Meza JL, et al. Reliability evaluation of the adapted national coordinating council medication error reporting and prevention (NCC MERP) index. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16: 1006–13

Rawlins MD. Clinical pharmacology: adverse reactions to drugs. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1981; 282: 974–6

Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Clarification of terminology in drug safety. Drug Saf 2005; 28(10): 851–70

Jonville-Béra AP, Saissi H, Bensouda-Grimaldi L, et al. Avoidability of adverse drug reactions spontaneously reported to a French regional drug monitoring centre. Drug Saf 2009; 32(5): 429–40

Anonymous. Failings in treatment advice, SPCs and black triangles. Drug Ther Bull 2001; 39(4): 25–7

Bates DW, O’Neil AC, Boyle D, et al. Potential identifiability and preventability of adverse events using information systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc 1994; 1(5): 404–11

Bobb A, Gleason K, Husch M, et al. The epidemiology of prescribing errors: the potential impact of computerized prescriber order entry. Arch Intern Med 2004; 164(7): 785–92

Kuo GM, Phillips RL, Graham D, et al. Medication errors reported by US family physicians and their office staff. Qual Saf Health Care 2008; 17: 286–90

van der Sijs H, Vulto A, Berg M. Overriding of drug safety alerts in Computerized Physician Order Entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006; 13: 138–47

Silverman JB, Stapinski CD, Churchill WW, et al. Multi-faceted approach to reducing preventable adverse drug events. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2003; 60(6): 582–6

Aronson JK. Medication errors: definitions and classification. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 67(6): 599–604

Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, et al. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. UCLA Division of Geriatric Medicine. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151(9): 1825–32

Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly: an update. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157(14): 1531–6

Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, et al. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163(22): 2716–24

Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, et al. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147(11): 755–65

Robertson HA, MacKinnon NJ. Development of a list of consensus-approved clinical indicators of preventable drug-related morbidity in older adults. Clin Ther 2002; 24(10): 1595–613

Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1990; 47: 533–43

MacKinnon NJ, Hepler CD. Indicators of preventable drug-related morbidity in older adults: 2. Use within a managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm 2003; 9(2): 134–41

Howard RL, Avery AJ, Howard PD, et al. Investigation into the reasons for preventable drug related admissions to a medical admissions unit: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 2003; 12(4): 280–5

Baena MI, Marin R, Martinez Olmos J, et al. Nuevos criterios para determiner la evidabilidad de los problemas relacionados con los medicamentos. Una revisión actualizada a partir de la experiencia con 2558 personas. Pharm Care Esp 2002; 4: 393–6

Olivier P, Caron J, Haramburu F, et al. Validation d’une éhelle de mesure: exemple de l’échelle française d’évitabilité des effets indésirables médicamenteux. Thérapie 2005; 60(1): 39–45

Winterstein AG, Sauer BC, Hepler CD, et al. Preventable drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharmacother 2002; 36(7–8): 1238–48

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to prepare this review. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the contents of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferner, R.E., Aronson, J.K. Preventability of Drug-Related Harms — Part I. Drug-Safety 33, 985–994 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2165/11538270-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11538270-000000000-00000